7 Psychological Thrillers

In “Heroes & Deus Ex Machina,” we explored films that had classic heroes at their heart. The characters – and films they inhabit – that are highlighted in this module are decidedly more . . . complex, with threats as much internal as external. The previous module also focused on blockbuster films, while here, we see films that more accurately could be called independent films, produced outside the major film studio system (like Marvel). These films tended to arrive later in the history of cli-films, although one early model for these was The Fire Next Time (2006). Set in bucolic Kalispell, Montana, against a backdrop of environmental issues like climate-change-fueled forest fires, the film focuses more on the conflicts that arise from those issues among the various and diverse townspeople, from “an incendiary talk show host to a tolerance-preaching ex-cop, from anti-environmental activists burning a green swastika to Native American families fleeing mounting racism.”[1] Director Patrice O’Neill suggests that the conflicts among the residents pose a greater existential threat than those from the environment around them.

One of my favorite, independent Cli-Fi Films is Take Shelter (2011), perhaps due to the brilliant lead performance by Michael Shannon. Shannon (who would go on to become an acclaimed actor) plays Curtis LaForche, who suffers from insomnia, apocalyptic dreams when he can sleep, and visions including rain “like fresh motor oil” and swarms of menacing black birds. He fears he may have inherited his mother’s paranoid schizophrenia but still obsessively builds a shelter to protect his family, his wife Samantha (Jessica Chastain) and their deaf daughter, Hannah. His bizarre behavior increasingly alienates him from them, his friends, employer, and the close-knit townspeople.

Curtis loses his job just before Hannah is about to get a cochlear implant, and tensions between him and Samantha begin to crescendo. Then, he gets into a fight with a friend at a community gathering, shouting that a devastating storm is coming and insisting that none of them are prepared. Afterward, a tornado warning leads the family to take shelter but Samantha is not convinced there is a real storm, leading to a climactic confrontation between the two. Curtis agrees to get help, and they embark on a vacation before he will leave to check into a psychiatric facility. But at the beach, as Hannah signs “storm,” a dark, oily rain begins to fall, the sky darkens, water spouts amass, and a tsunami forms in the distance. The musical undercurrent of strings adds to the tense urgency as the film comes to an end:

That scene gives me chills every time. Take Shelter was critically acclaimed; Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film four out of four stars and praised Shannon’s performance, writing, “Here is a frightening thriller based not on special effects gimmicks but on a dread that seems quietly spreading in the land: that the good days are ending, and climate changes or other sinister forces will sweep away our safety.”[2] It’s a masterful entry in this category of Cli-Fi Films, and a tough act to follow.

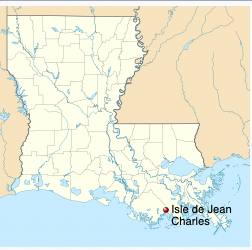

But the next year, Beasts of the Southern Wild (2012) proved another outstanding entry in the Cli-Fi Film psychological thriller sub-genre. Beasts is set on a fictional island in the Louisiana Bayou, “Isle de Charles Doucet,” known by the residents as the “Bathtub.” The island is in a vulnerable location beyond the levees built to protect the land and its residents from the hurricanes, erosions, storm surges, and rising seas that are becoming all too common in that area thanks to climate change. Director Benh Zeitlin claims that the Bathtub was inspired by Louisiana’s Terrebonne Parish, most notably the rapidly eroding Isle de Jean Charles. In January 2016, the state received substantial funding from the U.S. government to assist in the resident’s resettlement, making them among the country’s first climate refugees. It is against this backdrop that the imaginary but realistically vulnerable world of the film is set.

Beasts of the Southern Wild tells the story of six-year old Hushpuppy (Quvenzhané Wallis), for whom the island represents a natural world of wonder in which to explore and grow up. Her optimistic, wise-beyond-her-years belief in the balance of humans and nature is challenged as she comes to grips with her father’s illness and impending storms and floods that all threaten her existence and that of the island she calls home. The titular beasts are aurochs, prehistoric creatures Hushpuppy learns about in school, then imagines are released by melting ice, threatening the community and, lending a fantastical element to the film. Beasts is as much about Hushpuppy’s interior world/imagination, navigating real (poverty) and imagined (the aurochs) threats, and her relationship with her father and potential orphanhood, as it is a disaster/Cli-Fi Film, with the undercurrent of impending doom mirroring that of Take Shelter, with its focus on family and relationships between its member similar as well.

Beasts was critically acclaimed; like Take Shelter, Roger Ebert gave it a rave review, calling it a “remarkable creation. . . . Sometimes miraculous films come into being, made by people you’ve never heard of, starring unknown faces, blindsiding you with creative genius. ‘Beasts of the Southern Wild’ is one of the year’s best films.”[3] Wallis became the youngest ever nominee for the Academy Award for Best Actress for her portrayal of Hushpuppy. The film is a brilliant meditation on human’s often fractious relationship with the natural world, seen through the imaginative, hopeful eyes of a child, helping to make its themes around climate change accessible and compelling.

In stark contrast, the events of First Reformed (2017) are seen through the eyes of an alcoholic minister, Ernst Toller (Ethan Hawke), who leads a historic Dutch Reformed Protestant Church in upper New York. Toller counsels a radical, environmental activist whose despair over climate change leads him to suggest that his pregnant wife, Mary (Amanda Seyfried), abort their baby so it won’t have to live in an increasingly devastated world. After Toller discovers Michael dead from a self-inflicted gunshot to the head, he conducts the memorial service, held at the directions of the deceased at a toxic waste dump. One of the most affecting scenes in the film is during the service. Michael’s suicide note requested a specific song (sung by a youth church choir in a moment of brilliant and oxymoronic juxtaposition):

After that, Toller spirals into despair himself, suffering from memories of a son who died in the Iraq War, failing health, and increasing awareness, spurred by Michael and Mary, of the effects of climate change on the world around him. Woven throughout the film are images of those effects as Toller is drawn into activism himself, the film focusing on his interior monologues as he navigates his escalating despair. Like Beasts, there is a fantasy element as Toller and Mary become literally, physically intertwined, pressed together face-to-face, then (metaphorically, one presumes) float over images of a climate-ravaged world. Toller’s existential crisis comes to a head as he straps on a suicide vest left behind by Michael, with plans to detonate it at a church event where the head of a local polluting factory will be in attendance. The final scenes of the film are not for the faint of heart, and many viewers may find the ambiguous ending frustrating.

First Reformed, although not a box office hit, was critically acclaimed, receiving nominations at the Independent Spirit Awards for Best Film, and Best Director and Best Screenplay for Paul Schrader while winning the Best Male Lead for Hawke (Shrader was also nominated for an Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay). What I find particularly compelling about the film as not just a psychological thriller but a Cli-Fi Film as well, is its connection of climate change to religion. Toller even argues that climate change advocacy should be a mission of “The Church,” broadly conceived, on behalf of God and the nature he created under Judeo-Christian beliefs. This is a unique perspective among the films explored here.

The same year a polarizing film titled Mother!, directed by Darren Aronofsky and starring Jennifer Lawrence and Javier Bardem, premiered. In an interview, Lawrence stated that the film is an allegory that “depicts the rape and torment of Mother Earth.”[4] If so, it deserves a mention here, but only a mention, as it seems only very superficially a Cli-Fi Film. But if Mother! deserves only a mention, the final film featured here deserves more attention, even as it also at first appearance is only loosely connected to climate change.

Parasite (2019) was written (with Han Jin-won) and directed by Bong Joon-ho, who directed Snowpiercer five years earlier (see Chapter 5, Post-Climapocalyptic Dystopias). While Bong continues his interest in the effects of the environment on humans, Parasite differs from his earlier film in shifting from an action-oriented approach to a psychological thriller that borders on black comedy. The film revolves around two Korean families, the wealthy Parks and the poor Kims. As science writer Ben Goldfarb argues, “They’re divided not only by social status but by topography. The Parks live behind locked gates in a spotless, well-lit house, up a steep street in the Seoul highlands — a city on a hill. The Kims, who resourcefully infiltrate the Parks’ lives over the course of the movie, squat in a subterranean bunker in a low-elevation slum.”[5]

Parasite depicts how the Kims slowly, insidiously, and desperately infiltrate the home and lives of the Parks, while monsoons and floods threaten their world. It is a classic “upstairs/downstairs” story set in a modern world of class inequality and the indignities of capitalism (and the seemingly perpetual search for a WiFi signal). Less obviously, it illustrates the very real ways global warming worsens inequality, mirroring the themes – but through very different narrative and cinematic methods – of Snowpiercer.

A worldwide box office hit, Parasite set a new record for Bong, becoming the first of his films to gross over $100 million worldwide. It then went on to became the first Korean film to win the top prize, the Palme d’Or, at the Cannes Film Festival and the first non English-language film to win the Academy Award for Best Picture, among numerous other accolades. Although the well-deserved attention it received as a paragon of filmmaking rarely included mentions of its environmental backdrop, Parasite is one of the most impactful Cli-Fi Films, with its realistic depiction of modern climate inequality, as brilliantly indicated in one moment: the morning after the deluge that destroys the Kims’ home, the matriarch of the Park family chats on the phone with a friend from the backseat of her chauffeured car. “Did you see the sky today?” she asks. “Crystal clear. Zero air pollution. Rain washed it all away.” Her obliviousness mirrors the denial over climate change that is, unfortunately, the hallmark of our age – as brilliantly depicted in the final film explored in the next chapter (and this text), “Comedies.”

KNOWLEDGE CHECK

Videos

Take Shelter – Ending Scene: https://youtu.be/G_LWivXz6YM

BEASTS OF THE SOUTHERN WILD – Official Trailer: https://youtu.be/pvqZzSMIZa0

- “The Fire NextTime.” Amazon.com. Retrieved March 22, 2023. ↵

- Ebert, Roger (October 5, 2011). "Take Shelter." Rogerebert.com. Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved March 22, 2023. ↵

- Ebert, Roger (July 4, 2012). "Beasts of the Southern Wild." Rogerebert.com. Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved March 24, 2023. ↵

- White, Adam (September 16, 2017). "Mother! explained: what does it all mean, and what on earth is that yellow potion?" The Daily Telegraph. London, England. Retrieved March 28, 2023. ↵

- Goldfarb, Ben (February 28, 2020).”‘Parasite’ As Climate Fiction.” living on earth, Public Radio's Environmental News Magazine. Retrieved March 29, 2023. ↵