Evaluation

CHAPTER DESCRIPTION

- Defines judgments and criteria that are appropriate to the object of evaluation

- Evaluates using these judgments and criteria

- Includes a professional and student writing sample

Evaluation, Every Day

While some of us might struggle to define evaluation, we nevertheless use evaluation every day. Deciding on what to buy, what to eat, what classes to take: all of these activities involve a process of evaluation. Our opinion of these things takes into account all kinds of evidence, attitudes, and likes and dislikes.

So, in many ways, we will be familiar with the kind of paper that centers evaluation. The activities and assignments we will cover in this chapter differ somewhat from those everyday evaluations. We probably don’t have to make our judgments clear when we decide to eat cereal for dinner. Our thought processes and rationales don’t have to be written down, and we don’t need to appear unbiased. Our dinner, our opinions.

If you’ve ever read an article about the latest iPhone that told you whether or not it was worth the money, then you’ve read an evaluation essay. Other examples of evaluation essays are movie reviews, book reviews, restaurant reviews, or car reviews. The point of all these examples is to make a judgment about the subject; is it good or is it bad?

In this paper, and for this unit, we will see how these everyday evaluations become formal, as these papers require explicitly stated judgments, clear criteria, and statements about counterarguments.

These characteristics and the skills necessary to produce them will also prove useful in the chapter focused on Compare and Contrast.

The Purpose of Evaluative Writing

Writers evaluate arguments in order to present an informed and well-reasoned judgment about a subject. While the evaluation will be based on their opinion, it should not seem opinionated. Instead, it should aim to be reasonable and unbiased. This is achieved through developing a solid judgment, selecting appropriate criteria to evaluate the subject, and providing clear evidence to support the criteria.

Evaluation is a type of writing that has many real-world applications. Anything can be evaluated. For example, evaluations of movies, restaurants, books, and technology ourselves are all real-world evaluations. At your job, your manager may write a year-end evaluation of your performance, or you may be the one writing an evaluation of an employee, and these evaluations often impact your pay!

Evaluation is important because it is a bedrock and foundation for Compare-and-Contrast essays, which require evaluations of two or more different objects, events, or people, to judge them together and against each other.

The Structure of an Evaluation Essay

How do you structure an evaluation essay?

Subject

First, in an introduction, the essay will present the subject. What is being evaluated? Why? The essay begins with the writer giving any details needed about the subject. For example, a restaurant review must at least include the name and location of the restaurant. In an evaluation of a vehicle, you’d include the make, model, and year of the vehicle. If the essay were a movie review, this is where you’d tell us the name of the movie and give a little bit of background.

Even at this early stage, your evaluation of the subject can come into focus for your reader. Your word choice—the adjectives and adverbs you use—can make your judgment clear even before you state your thesis.

Judgment

Next, the essay needs to provide a judgment about a subject. This is the thesis of the essay, and it states whether the subject is good or bad based on how it meets the stated criteria. This is most often the very last sentence of the introduction. Again, if this were a movie review, this might be where you state that you liked (or disliked) the movie, and maybe a brief indication of why.

Don’t be afraid to take a strong stand! Don’t straddle the fence or water down your judgment. That means your thesis statement should not be a question. Your thesis should not offer up several different perspectives. Instead, make a bold, direct statement. Be clear, concise, and direct. Tell us what you really think!

Criteria

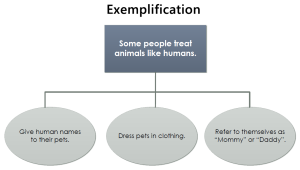

An important first step in writing an evaluation is to consider the appropriate criteria for evaluating the subject. Criteria are standards that we use when making a judgment.

If you were to evaluate a car, for example, you might consider the expected criteria: fuel economy, price, and crash ratings. However, you could also consider more personal criteria: style, color, sound systems, or whether it has Apple CarPlay. Even though not everyone will base their choice of a car on these secondary criteria, they are still okay to use in your essay; in fact, they can make the essay more personalized and interesting.

Job applications and interviews are more examples of evaluations. Based on certain criteria, management and hiring committees determine which applicants will be considered for an interview and which applicant will be hired.

How do you decide what criteria to use? Start by making a list of commonly used standards for judging your subject. If you do not know the standards usually used to evaluate your subject, you should start with some research. For example, if you are reviewing a film, you could read a few recent film reviews on Rotten Tomatoes, noting the standards that reviewers typically use and the reasons they give for liking or disliking a film. If you are evaluating a football team, you could read reviews of football teams on ESPN, find a book on coaching football, or talk to a football coach to learn about what makes a great (or not-so-great) football team.

You might mention your criteria in your introduction, or you might use the topic sentences of your body paragraphs to clearly identify your criteria. Sticking with the movie review example, you might explain that your criteria are the plot of the movie, the quality of the acting, and how well-made the movie is.

Evidence

The evidence of an evaluation essay consists of the supporting details authors provide based on their judgment of the criteria.

For example, if the subject of an evaluation is a restaurant, a judgment could be “Kay’s Bistro provides an unrivaled experience in fine dining.” Some authors evaluate fine dining restaurants by identifying appropriate criteria in order to rate the establishment’s food quality, service, and atmosphere. For example, if the bread served at the start of the meal was fresh out of the oven, then describing that fresh bread would be evidence in evaluation of the restaurant; it would fall under the criterion of “food quality.”

Another example of evaluation is literary analysis; judgments may be made about a character in the story based on the character’s actions, characteristics, and past history within the story. The scenes in the story are evidence for why readers have a certain opinion of the character, so you might include text from the story as evidence in your essay. You might also quote the published opinions of other writers who have already evaluated this story.

In a movie review, for each of the criteria that you stated, you’d provide specific evidence from the movie. Describe pivotal scenes that led to your judgment. For example, if a movie included a really emotional scene that stuck with you long after you saw the movie, you could cite that as evidence of the quality of the acting.

Counterargument

Counterarguing means responding to readers’ objections and questions. To effectively counterargue, you need to understand your audience. What does the audience already know? What do you think their opinions are? Do you expect your audience to agree or disagree with you?

Why bother with counterargument? Effective counterarguing builds credibility in the mind of the reader because it seems like you’re listening to their questions and concerns.

Typically, the best place for counterarguments is the end of the essay, after you’ve already made your points. Think about what objections you expect your reader to have. You can respond to those objections in two ways. The first option is to acknowledge an objection and immediately provide a counterargument, explaining why the objection is not valid. Second, you can concede the point, basically admitting there is room for other opinions. In either case, it is important to be respectful of opinions that are different from your own, while still standing behind your thesis.

Below is an example of a movie review. Now that you understand that a movie review is an evaluation essay that uses criteria and specific evidence to make a judgment on the subject, look for those criteria and evidence as you read. Does this critic use the same criteria that you do when deciding whether you like a movie?

Professional Writing Example

‘The Batman’ Is the Batman Movie We Deserve

By Adam Nayman

The Batman is not the Batman movie we need. That’s because we didn’t need another Batman movie. Not yet, anyway. Maybe if Christian Bale’s climactic self-sacrifice at the end of The Dark Knight Rises had hit a little bit harder, without the winking, now-you-see-him-now-you-don’t resurrection engineered by Christopher Nolan (still prestige-ing after all these years); maybe if we hadn’t had Ben Affleck glowering through various Snyder cuts like the human embodiment of a contractual obligation.

The Batman is the Batman movie we deserve, though: overwrought and overlong, but also carefully crafted and exhilarating. It’s just good enough to wish it were better—a lavish piece of intellectual property that ultimately prices itself out of providing cheap thrills.

Directed by Matt Reeves, The Batman begins like an exploitation movie, with a voyeuristic, quasi-Hitchcockian point-of-view shot seen through high-powered telescopic goggles—heavy breathing on the soundtrack and a family in the crosshairs. Shades, definitely, of Dirty Harry and its all-seeing sociopathic sniper, or maybe The Silence of the Lambs’ Buffalo Bill. As the sequence goes on, stitching us in complicity into an act of surveillance and then cutting stealthily into the home of Gotham’s embattled mayor (Rupert Penry-Jones), there’s a sense of dread that feels new and strangely alien compared to other iterations of the franchise. Nolan’s Dark Knight movies were grim and melodramatic and full of brutal, sadistic acts of violence, but they were never scary. The actors were having too much fun, and the over-cranked psychological intensity was subordinate to spectacle. Reeves, though, uses the visual vocabulary of a slasher movie for all it’s worth. When the owner of the original POV shot suddenly materializes in the shadows behind the mayor and dispatches him with a blunt instrument to the head, the effect is genuinely unsettling. We don’t feel safe.

Paranoia is in Reeves’s wheelhouse; at his best, he’s a fluid, moody virtuoso. Think of the excellent first half of Cloverfield, with its anxious first-person perspective on an impending apocalypse. Or the terrifying car-crash scene in his remake of Let Me In, which unfolds with the camera as a hapless backseat passenger, looking on unblinkingly as the world turns upside down. Reeves isn’t above show-offy camerawork, but it’s less to impart his own sense of control than to keep the audience off balance.

The tension, then, is between a filmmaker who specializes in disequilibrium tackling material that’s almost ritualistically familiar. For the first 45 minutes, The Batman does a beautiful job of giving us the beats that we expect, tricked up just enough to seem fresh. There’s a crime-riddled Gotham crisscrossed by low-level mobsters; the title character smacking down street-level hoods during his nightly rounds; and a police force resentful of the vigilante in their midst. We’ve seen it all before, but not usually with such a patient, arresting sense of confidence. When Robert Pattinson’s Batman stalks through the bloody crime scene at the mayor’s apartment, staring down the cops lining his path, the effect is pure pulp friction—a kind of vivid, scummy immediacy. And when Batman emerges from the shadows to pummel some face-painted gangbangers, the bleak imagery evokes vintage Frank Miller.

Miller’s 1987 DC comics arc Batman: Year One is an obvious inspiration for Reeves and Peter Craig’s screenplay, which makes it clear that Pattinson’s incarnation is still just experimenting with his nocturnal alter ego. In this version, Batman is less authentically world-weary than prematurely burned out—a nice Gen Z spin on the archetype. “Two years of nights,” he grumbles in voice-over sounding (purposefully) like Taxi Driver’s Travis Bickle or the Rorschach of Alan Moore’s 1986 graphic novel Watchmen. Miller’s vision of a Gotham City buckling under Reagan-era anxieties—nuclear proliferation, inner-city crime, encroaching spiritual malaise—remains deeply influential, even after Tim Burton’s gothic, expressionist Gotham. While Reeves’s style and color palette are different from Nolan’s, he’s equally interested in the Miller-derived idea of the city as psychic protagonist, with lots of earnest monologuing about whether such a corroded urban landscape is worth saving, or if a self-styled crime fighter is just wasting his time.

Once it’s clear that we’re going to be spared yet another version of Batman’s origin story—no flashbacks to his parents getting shot outside the opera or close-ups of a moony, grieving little Bruce Wayne—the novelty of watching a relatively fledgling superhero earning his wings kicks in. There’s probably less of Bruce Wayne in The Batman than any other movie version, and so the usual trick of having the star play up the differences between the two personas doesn’t apply. Pattinson’s skill at playing awkward, antisocial characters works well for a vigilante who cloaks himself in solitude and isn’t interested in making friends (except for Jeffrey Wright’s nicely soulful James Gordon, imagined here as a principled wingman rather than a head honcho). That said, it’s not like there are any galas or fundraisers for Bruce to attend anyway. The only time he’s called on to appear in public is at the mayor’s funeral, which ends up turning into a murder scene as well at the whim of the masked killer whose sporadic appearances drive the story and punctuate it with a series of question marks.

It’s telling that Reeves went with the Riddler as the main bad guy for his first crack at the Batman universe. For one thing, it’s not like Paul Dano has to compete with a universally acclaimed movie take on the role. (Almost 30 years later, we still cannot sanction Jim Carrey’s buffoonery in Batman Forever.) For another, the character’s enigmatic shtick is easily torqued into the kind of taunting, Zodiac-style cryptography that Reeves is using as a visual motif. (The Fincher comparisons also extend to Se7en, right down to the Riddler collecting his scribblings in a series of unmarked notebooks; the line between theft and homage remains razor-thin.) Dano, who’s usually cast as a punching bag, is impressively creepy in small doses, and disappears for long stretches that leave us wanting more.

The complexity of The Batman’s narrative is both a bug and a feature. Reeves is going for something sprawling, and there are subplots for Zoë Kravitz as a subtly feline, cat-burglarizing Selina Kyle and Colin Farrell as a mobbed-up, battle-scarred, humorously ineffectual Penguin. (As usual, Farrell is at his best when playing against his leading-man looks; his middle-aged transformation into a master character actor is something to behold.) They both work for suave crime boss Carmine Falcone (John Turturro), who’s got the cops in his pocket and a nebulous connection to the late Thomas Wayne, imagined here as a good-hearted but hardly flawless father and magnate with skeletons in his walk-in closet. The big through line is the idea that the Riddler’s victims are all connected to some dark, heartbreaking civic secret, one that also implicates the Wayne family, and the clues are parceled out judiciously, with enough mystery and flourish to suggest that the revelation will be worth the wait.

Sadly, it isn’t—not quite, and definitely not after more than two hours of portentous buildup involving loaded references to rats, moles, and other nocturnal animals. It’s bizarre how closely Reeves and Craig bump up against a potentially audacious twist without pulling the trigger; the way the story is shaped, it seems like Dano’s and Pattinson’s characters are supposed to be secret siblings as opposed to two different case studies in forlorn orphan psychology. The theme of duality between Batman and his foes—already stomped into the ground by Nolan, Burton, and pretty much everyone else who’s had a crack at the character—rears its head here, but not as disturbingly as the filmmakers seem to think. A big, late confrontation between Pattinson and Dano strives for the sociopathic chill of Se7en but feels lukewarm, as does the revelation that one of the film’s characters has been gradually amassing an army of similarly aggrieved, incel-style acolytes—the same idea that Todd Philips already (and more effectively) evoked in Joker.

The bigger problem is that having finally unraveled every tightly wound strand of its narrative, The Batman takes an exhausting swing at apocalyptic grandeur. For all the expectations that Reeves is trying to subvert or at least play with, he’s as susceptible to the lure of blockbuster-sized spectacle as Burton or Nolan. The carnage is well-staged on a technical level, but it’s weirdly desultory, even as it pushes topical hot buttons around the idea of armed, civic insurrection. Based on shooting dates, The Batman’s striking evocations of January 6 must be coincidental, but either way, it feels like Reeves and his collaborators are trying to capitalize on a melancholy, disenfranchised zeitgeist more than actually saying anything about it.

As for what they’re saying about Batman—that it’s a lousy, lonely job, but somebody’s gotta do it—suffice it to say that it’s all been said before. One reason that Michael Keaton’s interpretation of Bruce Wayne holds up is that he was able to retain a sense of ridiculousness; Pattinson’s a terrific actor and his gaunt jaw line and bruised, battered body language are striking, but he’s acting in such a narrow emotional range that, for the first time after a killer run of performances, he grows monotonous (especially when no-selling Kravitz’s come-ons). A Batman who listens to MTV Unplugged in New York on repeat is a perfectly OK idea in theory, but there’s Something in the Way that Reeves piles on signifiers of tragic alienation that just feels pretentious. It’s the same mock gravitas as when he used “The Weight” to score a moment of lyrical down time during Dawn of the Planet of the Apes, as if trying to channel the ghost of Easy Rider into a story about mutated chimpanzees firing guns on horseback.

“Vengeance won’t change the past,” Bruce Wayne observes late in The Batman. “People need hope.” There are worse thesis statements to base a movie around. But there’s also something disingenuous about a movie that drenches itself in unpleasantness before trying in the end to peddle uplift and recast the title character as a kind of humanitarian activist. Ultimately, this Batman accepts the thankless, death-defying role he’s stepped into, and the sacrifices that go with it. But that choice would be more compelling if it weren’t framed as a tacit acknowledgement of all the inevitable sequels to come—whether we need them or not.

Discussion Questions

- How does the essay serve as an evaluation essay? In other words, what judgment is it making?

- What are the criteria Nayman uses to judge Batman as a franchise? What criteria does he use to judge the newest Batman movie?

- How does Nayman address counterarguments?

- What kinds of evidence does he use and from what sources?

- Whether or not you’ve seen The Batman, do you agree with Nayman’s judgment about the movie? Explain your answer.

Student Writing Example

Sample Essay

Gender differences and biases have been a part of the normal lives of humans ever since anyone can remember. Anthropological evidence has revealed that even the humans and the hominids of ancient times had separate roles for men and women in their societies, and this relates to the concepts of epistemology. There were certain things that women were forbidden to do and similarly men could not partake in some of the activities that were traditionally reserved for women. This has given birth to the gender role stereotypes that we find today. These differences have been passed on to our current times; although many differences occur now that have caused a lot of debate amongst the people as to their appropriateness and have made it possible for us to have a stereotyping threat by which we sometimes assign certain qualities to certain people without thinking. For example, many men are blamed for undermining women and stereotyping them for traditional roles, and this could be said to be the same for men; men are also stereotyped in many of their roles. This leads to social constructionism since the reality is not always depicted by what we see by our eyes. These ideas have also carried on in the world of advertising and the differences shown between the males and the females are apparent in many advertisements we see today. This can have some serious impacts on the society as people begin to stereotype the gender roles in reality.

There has been a lot of attention given to the portrayal of gender in advertising by both practitioners as well as academics and much of this has been done regarding the portrayal of women in advertising (Ferguson, Kreshel, & Tinkham 40-51; Bellizzi & Milner 71-79). This has led many to believe that most of the advertisements and their contents are sexist in nature. It has been noted by viewing various ads that women are shown as being more concerned about their beauty and figure rather than being shown as authority figures in the ads; they are usually shown as the product users. Also, there is a tendency in many countries, including the United States, to portray women as being subordinate to men, as alluring sex objects, or as decorative objects. This is not right as it portrays women as the weaker sex, being only good as objects.

At the same time, many of the ads do not show gender biases in the pictures or the graphics, but some bias does turn up in the language of the ad. “Within language, bias is more evident in songs and dialogue than in formal speech or when popular culture is involved. For example, bias sneaks in through the use of idiomatic expressions (man’s best friend) and when the language refer to characters that depict traditional sex roles. One’s normative interpretation of these results depends on one’s ideological perspective and tolerance for the pace of change. It is encouraging that the limited study of language in advertising indicates that the use of gender-neutrality is commonplace. Advertisers can still reduce the stereotyping in ad pictures, and increase the amount of female speech relative to male speech, even though progress is evidenced. To the extent that advertisers prefer to speak to people in their own language, the bias present in popular culture will likely continue to be reflected in advertisements” (Artz et al 20).

Advertisements are greatly responsible for eliciting such views for the people of our society. The children also see these pictures and they are also the ones who create stereotypes in their minds about the different roles of men and women. All these facts combine to give result to the different public opinion that becomes fact for many of the members of the society. Their opinion and views are based more on the interpretation they conclude from the images that are projected in the media than by their observations of the males and females in real life. This continues in a vicious circle as the media tries to pick up and project what the society thinks and the people in the society make their opinions based upon the images shown by the media. People, therefore, should not base too much importance about how the media is trying to portray the members of the society; rather they should base their opinions on their own observation of how people interact together in the real world.

Works Cited

Artz, N., Munger, J., and Purdy, W., “Gender Issues in Advertising Language,” Women and Language, 22, (2), 1999.

Bellizzi, J. A., & Milner, L. “Gender positioning of a traditionally male-dominant product,” Journal of Advertising Research, 31(3), 1991.

Ferguson, J. H., Kreshel, P. J., & Tinkham, S. F. “In the pages of Ms.: Sex role portrayals of women in advertising,” Journal of Advertising, 19 (1), 1990.

Discussion Questions

- What is the topic or phenomenon being evaluated in the example essay above?

- What are the criteria for evaluating it?

- Look for examples of opinion or bias—where are they?

- What kinds of evidence does this essay use?

- Do you find yourself agreeing or disagreeing with the writer’s judgment? Explain.

Your Turn

- Evaluate a restaurant. What do you expect in a good restaurant? What criteria determine whether a restaurant is good?

- List three criteria that you will use to evaluate a restaurant. Then dine there. Afterward, explain whether or not the restaurant meets each criterion, and include evidence (qualities from the restaurant) that backs your evaluation.

- Give the restaurant a star rating (5 Stars: Excellent, 4 Stars: Very Good, 3 Stars: Good, 2 Stars: Fair, 1 Star: Poor). Explain why the restaurant earned this star rating.

Key Terms

- Judgment

- Opinion

- Bias

- Evidence

- Criteria

- Counterarguing

Summary

While we surely evaluate things and activities every day, now we can see how our judgment of something based on criteria and supported by evidence can create an essay that does more than simply review but analyzes and evaluates in a way that avoids bias and unsupported opinion.

[h5p id=”23″]

[h5p id=”24″]

[h5p id=”25″]

Reflective Response

How would you evaluate your own progress in completing these readings and assignments that focus on evaluation—what could you have done differently?

Sources

This chapter has been adapted and remixed by Will Rogers from the following textbooks and materials: English Composition licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License and OER material from Susan Wood, “Evaluation Essay,” Leeward CC ENG 100 OER, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This chapter is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License; It can be found at lms.louislibraries.org under this same license.

“‘The Batman’ is the Batman Movie We Deserve” by Adam Nayman appeared online in The Ringer on March 8, 2022. All rights reserved.

CHAPTER DESCRIPTION

- Chapter discusses good reasoning and arguments, how we reason, and intellectual virtues

The life according to reason is the best and the pleasantest, since reason, more than anything else, is human. This life therefore is also the happiest.

—Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics

Rational, adj. Devoid of all delusions save those of observation, experience, and reflection.

—Ambrose Bierce, The Devil’s Dictionary

1.1 GOOD REASONING

You know the answers to many of the questions you care about, but you merely have opinions about many others. What is the difference between knowledge and opinion? Why is it that you now know, for example, that your teacher is highly competent, even though at one time this was only your opinion? The answer has partly to do with your level of confidence; although once you believed it tentatively, you now believe it with assurance. But there is a deeper difference: you now have better reasons for believing it. You have read her student evaluations, talked to many of her former students, maybe even taken a class from her yourself. There might still be some remote chance that she will disappoint you. (If it does turn out that you have been misled, you will conclude that it was merely an opinion all along—that you thought you knew that she was highly competent, but you never really knew it.) But, from where you now sit, your reasons are so good that you do justifiably claim it as knowledge and not as mere opinion.

So an important difference between knowledge and mere opinion is the quality of your reasons. Your reasons are what you depend on in support of what you believe—regardless of whether you consider what you believe to be knowledge or mere opinion. There are many rough synonyms for reasons: evidence, warrant, justification, basis, grounds, rationale, and—the term we will rely on most heavily—premises.

Typically, reasons are something you have, while reasoning is something you do. The term reasoning refers here to the attempt to answer a question by thinking about reasons, as in the sentence He stood in the polling booth, reasoning one last time about the relative merits of the two candidates. Good reasoning is the thinking most likely to result in your having good reasons for your answers—and, thus, the sort of thinking most likely to give you knowledge rather than mere opinion.

Good reasoning, as Ambrose Bierce hints in the lead quotation, does not guarantee anything. Even with the best of reasoning you might still end up with a false belief and thus fail to have knowledge. Consider those before the time of Copernicus who believed that the sun orbited the Earth. Given the limited information available to them, there was nothing wrong with their reasoning. But their belief was false, and thus they did not know that the sun orbited the Earth. But the fallibility of good reasoning is no basis for rejecting it. There is simply no infallible substitute for it. And it is by continuing to reason well in the presence of new information that you learn that some of your beliefs are false—for example, that it is actually the Earth that orbits the sun.

Aristotle, in the other lead quotation, may be overenthusiastic in saying that good reasoning leads to the best, pleasantest, and happiest life. Some people might benefit from concentrating a little less on reason and a little more on friendship and human kindness—though, Aristotle might reply, the right use of reason—good reasoning—would tell them just that! Good reasoning does make an enormous contribution to a good life. For answering the questions you care about, knowledge is better than mere opinion and, thus, good reasoning beats bad reasoning.[1]

1.2 GOOD ARGUMENTS

Arguments

Arguments are the means by which we express reasons in language. For now, consider the following brief definitions. An argument is a series of statements in which at least one of the statements is offered as a reason to believe another. A premise is a statement that is offered as a reason, while a conclusion is the statement for which reasons are offered.

Here is a typical everyday argument. Suppose you realize that you’ve broken out in hives and you wonder aloud what happened. I try to solve it for you as follows:

Look at those hives! You only break out like that when you eat garlic—so there must have been garlic in that sauce you ate.

This argument provides two closely related reasons to believe its conclusion. The conclusion is this:

Conclusion: There was garlic in the sauce you ate.

The reasons, or premises, are these:

Premise one: You have hives.

Premise two: You get hives when you eat garlic.

Here is a slightly more elaborate argument from The Panda’s Thumb by Stephen Jay Gould. Gould wonders whether a larger animal, in order to be as smart as a smaller animal, must have the same ratio of brain size to body size; his answer is as follows:

As we move from mice to elephants or small lizards to Komodo dragons, brain size increases, but not so fast as body size. In other words, bodies grow faster than brains, and large animals have low ratios of brain weight to body weight. In fact, brains grow only about two-thirds as fast as bodies. Since we have no reason to conclude that large animals are consistently stupider than their smaller relatives, we must conclude that large animals require relatively less brain to do as well as smaller animals.

Gould expresses in language his reasons for believing his answer to the question—that is to say, he has provided us with an argument. The answer, his conclusion, is this:

Conclusion: Larger animals require relatively less brain to do as well as smaller animals.

And his reasons, or premises, are these:

Premise one: In comparing smaller types of animals to larger types of animals, brains increase only about two-thirds as fast as bodies.

Premise two: Larger animals are not consistently stupider than their smaller relatives.

Good Arguments

Four things are required of a good argument. First, the premises must be true—that is, the premises must correspond with the world. Typically, this can be decided about each premise independently, without paying any attention to the other premises or to the conclusion. So, the garlic argument would be defective if, say, contrary to its first premise, you didn’t have hives. Gould’s argument would be defective if, say, contrary to its second premise, larger animals were consistently stupider than smaller ones.

Second, the argument must be logical—that is, the premises must strongly support the conclusion. They must make it reasonable for you to believe the conclusion. This can normally be decided without paying any attention to whether the premises or conclusion are true. Suppose the conclusion to the garlic argument were There was pepper in the sauce you ate, or that Gould’s conclusion were Larger animals require relatively more brain to do as well as smaller animals. It would then not matter whether the premises were true, or, for that matter, whether the conclusions were true. The arguments would be flawed anyway, since the premises, as stated, clearly do not support such conclusions. Regardless of whether the premises are true, the arguments would not be logical.

Truth and logic are the most important merits of arguments. If an argument has both merits—if its premises are true and it is logical—then it is sound. But if it is defective in even one of these two ways, it is unsound.

Third, the argument must be conversationally relevant—that is, the argument must be appropriate to the conversation, or to the context, that gives rise to it. Conversations—between two people, between author and audience, or even between arguer and imaginary opponent—generate questions, and arguments are typically designed to answer such questions. In the garlic argument I am interested in the question, Why do you have hives? But suppose I had misunderstood your question in the noisy restaurant; you hadn’t yet noticed that you had broken out in hives, and what you actually wondered aloud was why you had chives, since you had ordered your baked potato plain. My argument may still be perfectly sound—with true premises and good logic—yet it is now clearly defective, since it misses the point. This is not the only kind of conversational irrelevance. In Gould’s argument, suppose he answered the question asked, but in doing so had adopted this as his premise:

Larger animals require relatively less brain to do as well as smaller animals.

But this, of course, is identical to his conclusion! Gould would be offering as a premise the very thing that, in this particular conversation, is in question. Even if this premise were true, and even if the logic of the argument were good, the argument would be defective; for Gould would be helping himself to the answer without offering any reason for it.

Fourth, the argument must be clear. This means the language in which the argument is expressed must not thwart the decisions about whether the premises are true, whether the argument is logical, and whether it is conversationally relevant. Gould, for example, uses the phrase bodies grow faster than brains. This could mean, on the one hand, that as any individual grows, its body grows to its full size more rapidly than its brain grows to its full size. This, of course, is false. But, on the other hand, bodies grow faster than brains could mean that as you progress along a scale from smaller-bodied animals to larger-bodied animals, the brain size of the animal does not increase at the same rate as does the body size. The context makes it clear that this is what Gould means, and, since I have good reason to accept Gould’s expertise in this field, I readily accept it as a true statement. If we did not have the context that Gould does provide, we would not be able to decide whether this sentence was true or false, for it would not have the merit of clarity.

Three of the requirements are kinds of fit: the fit of the premises with the world (truth), the fit of the conclusion with the evidence (good logic), and the fit of the argument with the conversation (conversational relevance). And the fourth requirement is that it must be possible to tell whether these three kinds of fit exist (clarity).

The Merits of Arguments

- True premises

- Good logic

- Conversational relevance

- Clarity

The first two constitute soundness.

Arguments Are Models of Reasoning

Arguments are important for reasoning because part of their function is to provide models, made of words, that represent reasoning—verbal models that are especially designed to allow thinking to be examined and evaluated.

Keep in mind that a model contains only selected features of the object or event that it represents. An engineer who wants to design a car with reduced wind drag, for example, creates a model of the car for use in a wind tunnel. The model, however, represents only the external surfaces of the car and ignores such things as tread design, upholstery, and sound system.

Similarly, even a very good argument drops some of the features of reasoning, because it is usually not necessary to represent all the surrounding activities, such as the actual thought processes that produced it or the flash of insight that gave rise to the ideas behind it. Nor is it usually necessary to represent every piece of marginally relevant information. What matters most to the quality of the reasoning are the conclusion and the chief reasons behind it; and these are the features that arguments ordinarily display.

Throughout this text, we will be looking most closely at arguments as they are found in the language of daily life. As we shall see, these arguments are seldom offered solely as models of reasoning; they are usually also designed to persuade. One concern of this book is to learn how to clarify such arguments—to reduce them to their essential elements—so that most of what does not bear on good reasoning drops out.

1.3 HOW WE NORMALLY REASON

Edmund Halley, later to be immortalized by the comet named after him, once asked Isaac Newton how he knew a certain law of planetary motion. Newton replied, "Why I’ve known for years. If you’ll give me a few days, I’ll certainly find you a proof of it."

Reflect for a moment on how you think. Do you deliberately, meticulously work out the proofs for everything you believe? If you are like Sir Isaac Newton and the rest of us, you do so rarely[2]. You have too many questions, too much evidence, and too little time to consciously construct perfect arguments for every belief. Perhaps you typically have many reasons for your beliefs, but it may not always be necessary—or even possible—for you to consciously think them through. You intuitively use your reasons, consciously using only a variety of quick-and-dirty shortcuts to finding the answers. When, for example, you arrive at a store at 6:05 p.m. and find the windows dark, you conclude the store is closed without consciously reasoning to this conclusion. The similarity of this experience to others—not a meticulously constructed argument—convinces you that you will not be able to buy a new shirt that night. We will refer to these as shortcuts in reasoning. A more formal term is judgmental heuristics. (Heuristic is closely related to the word eureka, which is Greek for “I found it!” According to legend, Archimedes shouted “Eureka” as he ran naked through the streets of ancient Athens, having hit upon an important idea while in the bathtub.)

1.3.1 Some Common Shortcuts in Reasoning

You will find many of these shortcuts familiar, and you will see that often more than one shows up in the same bit of thinking.

First, there is the vividness shortcut (or what psychologists call the availability heuristic). You probably tend to rely heavily on whatever information is the most vivid. This can be a good thing; it is partly why, when deciding whether you should cross the street, you pay more attention to the screaming siren of the oncoming fire engine than to the walk signal (and thus avoid being flattened). But the most vivid information will not always lead you to the correct conclusion. For example, your single disastrous experience with an unreliable Dyson might lead you to conclude that Dysons are inferior vacuum cleaners, though you have also read a page full of monotonous statistics in Consumer Reports showing that they are among the best. If you based your purchasing decision on your single unpleasant (but unforgettable) experience, you might rule out a perfectly acceptable appliance.

Second, you probably tend to rely on quickly noticed similarities between the familiar and the unfamiliar. If you liked Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing, for example, you might expect to like his later movie, BlacKkKlansman, as well. This is the similarity shortcut (or what psychologists term the representativeness heuristic). This often works well to lead you to the correct conclusions, but significant dissimilarities may also exist between two partly similar things. You might expect, for example, a new acquaintance with a German accent to be good at math because she reminds you of your college math professor, who spoke with a similar accent. Too often you will be disappointed in this kind of expectation.

And third, you probably tend to preserve beliefs you have previously adopted. Believing that you do better on exams after a good night’s sleep, you would probably not carefully reevaluate that belief before you decide to go to bed reasonably early the night before you take a critically important exam. This tendency, which we call the conservation shortcut, is often appropriate; after all, you did have good reasons for your belief if you were reasoning well when you first adopted it. Sometimes, however, this tendency persists even when evidence for the belief has been discredited. If, for instance, you were told that a co-worker had taken credit for your project, you may find yourself continuing to mistrust your co-worker even after you discover that the person who told you was lying.

Shortcuts in Reasoning: Judgmental Heuristics

- Vividness—relying on the most vivid information.

- Similarity—relying on similarities between the familiar and the unfamiliar.

- Conservation—preserving previously adopted beliefs.

1.3.2 Having Reasons without Thinking about Reasons

In some cases, the thinking that leads us to arrive at a belief has nothing to do with our reasons for the belief. For example, 19th century chemist Friedrich Kekule was pondering the 40-year-old question of the structure of the benzene molecule when, slipping into a dream, he saw a roughly hexagonal ring in the flames of his fireplace. It dawned on him: the benzene molecule is hexagonal. Seeing the shape in the flames gave him the idea; that was a part of his finding the shape of the benzene molecule. But he did not consider the dream to be a reason to believe that the benzene molecule was hexagonal. Neither he nor anyone else would have concluded that the benzene molecule was square if Kekule had dreamed a square shape in the flames instead. The reasons that Kekule had for the belief only had to do with how well the theory of the hexagon fit the evidence he had accumulated. Getting an idea is one thing. Having support for the idea is quite another.[3]

In other cases, beliefs just seem to happen with no conscious consideration of the question. You look at your watch and you believe it is noon, or you glance out the window and believe it is raining, or you read the business headlines and believe that the Dow rose 27 points. An important reason you have for believing these sorts of things is your belief that this source of information is normally reliable—although that reason never actually crosses your mind.

The reasons that you have for believing something may be very different from what you were thinking about when the belief occurred to you. These reasons are what, in the end, matter most—not the activity that gets you there.

EXERCISES Chapter 1, set (a)

For each passage below, state the shortcut that is probably being used and explain how it has apparently failed or succeeded.

Sample exercise. Two psychologists write, “The present authors have a friend who is a professor. He likes to write poetry, is rather shy, and is small in stature. Which of the following is his field: (a) Chinese studies or (b) psychology?” Most people, they say, answer that it must be Chinese studies.—Richard Nisbett and Lee Ross, Human Inference

Sample answer. Similarity. For most people, the description is more similar to the mental image that they have of an Asian scholar than of a psychologist. But this is likely to lead to a mistake, since psychology is a huge field of study, especially compared to Chinese studies, and there are surely far more small, shy, and poetic psychologists than Asian scholars (even if a larger proportion of Asian scholars are like this). Further, the two psychologists are more likely to know other psychologists than they are to know professors of Chinese studies.

- When I was in the market for a used car, I commented to a friend that there were far more cars parked on the street with “For Sale” signs on them.

- Subjects in an experiment watched a series of people take a test—multiple choice, 30 problems, and each problem roughly equal in difficulty. By design, the test taker always solved 15 problems; but in some cases most of the 15 were solved early in the test, in other cases most were solved late. When the problems were solved early, the test takers were judged by the subjects to be more intelligent than when the problems were solved late, and they were credited with solving more problems than they actually had solved.

- “We had the sky up there, all speckled with stars, and we used to lay on our backs and look up at them, and discuss about whether they was made or only just happened. Jim he allowed they was made, but I allowed they happened; I judges it would have took too long to make so many. Jim said the moon could ‘a’ laid them; well, that looked kind of reasonable, so I didn’t say nothing against it, because I’ve seen a frog lay most as many, so of course it could be done. We used to watch the stars that fell, too, and see them streak down, Jim allowed they’d got spoiled and was hove out of the nest.”—Mark Twain, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

- Subjects in an experiment were asked to discriminate between real and fake suicide notes. They were periodically told during the experiment whether their performance was average, above average, or below average. Afterward, the experimenters explained convincingly to each subject that the feedback they had been given was unconnected to their performance—that the feedback had been randomly decided before they had even started. Nevertheless, the subjects’ answers to a final questionnaire showed that they continued to evaluate themselves as good at this sort of task if the feedback had been positive and bad at it if the feedback had been negative—even though that feedback, the only evidence they had, had now been discredited.—Richard Nisbett and Lee Ross, Human Inference

EXERCISES Chapter 1, set (b)

Come up with examples, either invented or actual, of the use of each of the three shortcuts—vividness, similarity, and conservation—in everyday situations.

1.4 INTELLECTUAL VIRTUES

Chances are that your thinking typically follows shortcuts that run along grooves deeply worn into your mind. It probably isn’t possible to eliminate them. Nor is it desirable. Successful living in this complicated world demands shortcuts, and these particular ones probably often do serve you well—but almost certainly could serve you better.

What is possible and desirable is that you develop other grooves that run just as deep—habits of thinking that can help you get to the right destination even when you do take shortcuts. These are intellectual virtues, that is, habits of thinking that are conducive to knowledge, habits that make it more likely that the answers you arrive at are well reasoned. Three virtues are especially important—the virtues of critical reflection, empirical inquiry, and intellectual honesty. The path to good reasoning is the cultivation of these three habits.

The Virtue of Critical Reflection

In The Lyre of Orpheus, novelist Robertson Davies describes the mental clutter of one of his characters as follows:

He had discovered, now that he was well into middle age, that . . . his mental processes were a muddle, and he arrived at important conclusions by default, or by some leap that had no resemblance to thought or logic. . . . He made his real decisions as a gifted cook makes soup: he threw into a pot anything likely that lay to hand, added seasonings and glasses of wine, and messed about until something delicious emerged. There was no recipe and the result could be foreseen only in the vaguest terms.

I do not propose that there is a recipe. But if his muddle sounds familiar to you, you can do something to introduce a bit more order. You can cultivate the virtue of critical reflection, that is, the habit of asking what the arguments are for your beliefs and whether those arguments are sound, clear, and relevant.

This is termed critical reflection since it requires reflection to answer the first part of the question—to detect what your reasons actually are—and it requires criticism to answer the second—to evaluate those reasons to determine how sound, clear, and relevant they are.

This is not a question that should or could be asked for every belief you adopt. But it is always appropriate to ask it when the question is important to you and when time allows. (In addition, it is often appropriate when your view is challenged.) When deciding what sentence to utter next in a casual conversation, conscious critical reflection is not called for—in fact, it could seriously impede the progress of your chat. When, on the other hand, you must decide where to attend college or what career to pursue, critical reflection can make the difference between a good choice and a poor one. Consciously engaging in critical reflection when it is appropriate helps to cultivate the habit so that your instincts are sharpened for those cases when you cannot consciously do it.

Reasoning is in some ways like snowboarding or speaking a foreign language. Often you can do it well by doing it instinctively—with no conscious thought of any formal principles. Nevertheless, it is possible to formally state what you must do to do it well, just as in how-to-snowboard videos or grammar books for a language. And spending a certain amount of time drilling—consciously applying the formal principles to the activity—means that on other occasions you will do it more successfully. Cultivating the virtue of critical reflection—the habit of expressing and evaluating arguments in words—means that when you must reason instinctively (i.e., when you do not have the time to express and evaluate the arguments), you will reason more successfully.[4] You will continue to use shortcuts like vividness, similarity, and conservation, but they will take you in the wrong direction much less often.

The Virtue of Empirical Inquiry

Another important intellectual virtue is the virtue of empirical inquiry, the habit of seeking out new evidence from the world around you in order to better answer your questions. (The word empirical means having to do with sense experience—that is, having to do with information gathered by seeing, hearing, tasting, smelling, or feeling.)

Let us say you are puzzled by a certain senator’s support for legislation that would open large tracts of previously protected wetlands to development. Upon critical reflection you might conclude that you have no good answer to the question, Why does she support this legislation? Many at this point are tempted to take the easy way out and adopt one of many possible unsupported answers. The only way to explain the senator’s support for that legislation is that she’s being paid off by industry/running for president/insensitive to her constituents/stupid—take your pick.

If you don’t care a great deal about the question, then, with such meager evidence, simply admit that you don’t know. But if you really do want to know the answer, this is where empirical inquiry comes in. Empirical inquiry is the patient collection of whatever additional information is required to come up with a good answer. It includes such activities as making observations, setting up experiments, studying, doing research, and talking to experts, thereby gathering new evidence—new reasons—which must then be formulated into arguments and subjected to critical reflection.

Inquiry into the question of the senator’s support for the legislation might show that she acted on the testimony of a number of impartial experts who stated definitively that the wetlands had been misidentified as such, and that they had no particular environmental importance. While you might still disagree with the senator’s decision, your inquiry will at least have provided a good answer to your question about her motivations.

The Virtue of Intellectual Honesty

If you are like most people, you sometimes don’t do what you ought to do—simply because you don’t want to. Physical exercise is easy to skip when you’re tired, busy, or just feeling lazy. To keep at it, you have to continually remind yourself of the goal—good health and all the benefits it brings—and get in the habit of pursuing it. Similarly, to reason well, it is important that the habits of doing the right thing—critical reflection and empirical inquiry—are combined with consistently wanting the right thing. And the right thing to want, in the case of good reasoning, is knowledge of the truth. The virtue of intellectual honesty is the habit of wanting, above all, to know the truth about the questions you care about. To sincerely ask a question is to want to know the truth about the question; to want something other than knowledge of the truth is to be insincere in asking the question—that is, it is to be intellectually dishonest.

In early 1986, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) was under an enormous amount of pressure. It had been more than 15 years since it had triumphantly put Neil Armstrong on the moon. NASA’s next major triumph was supposed to have been the space shuttle. It would fly as many as 60 times a year, NASA had predicted, thereby providing increasingly cheap transportation and an inexpensive platform for an array of scientific experiments. But it had not worked out that way. In 1985, due to a variety of technical glitches, there had been only five launches. NASA’s leaders were desperate for success. They viewed the approaching launch of the space shuttle Challenger, scheduled for January 28, with a strong sense of determination.

The rest of the story is well known. When engineers at Morton Thiokol (where the rocket boosters for the shuttle had been built) heard that Cape Canaveral temperatures were below freezing, they were alarmed. They feared that the O-rings that sealed the fuel containers on the boosters were not resilient enough to maintain a perfect seal in the cold. They notified their top managers, who notified NASA: the launch must be postponed until the arrival of warmer weather. But NASA officials refused to be convinced; reconsider your recommendation, they told Morton Thiokol, in a way that suggested future NASA business might otherwise go elsewhere. Morton Thiokol management finally caved in, overrode the engineers, and told NASA what NASA wanted to hear. NASA now had the evidence it needed to support the belief it wanted, and the schedule would be kept. Thiokol’s engineers, watching anxiously on TV, feared the shuttle would explode on the launching pad. As it cleared the pad, one of them whispered, “We dodged a bullet.” A few seconds later seven astronauts plummeted to their deaths.[5]

NASA officials were concerned about whether it was safe to launch the Challenger. But their chief desire, it seems, was not to know the truth, but to get whatever evidence it took to support the answer they wanted. They were not intellectually honest.

This virtue shows up most clearly as the willingness to consider any answer to a question so long as it is reasonable—that is, so long as the evidence for the answer holds some promise. This does not mean that you should never confidently hold onto your beliefs in the face of opposing evidence; you should remain confident when the weight of the evidence is clearly on your side. It does mean that you should cultivate the habit of seriously considering the opposing evidence even if you do confidently hold to your own answer. The virtue is not in drifting wherever the winds blow, but in being ready to test the winds in case they do warrant a change of course.

Intellectual honesty is displayed by the professor who sincerely grants that his star student may have identified a crucial error in his famous book, by the scientist who takes seriously an easily concealed experimental anomaly, by the politician who carefully reconsiders her own widely advertised bill on the grounds that legislation offered by the opposing party just might better address the social problem, and by the police officer who wonders whether the light really might have been yellow. We might just as easily term this virtue open-mindedness—openness to all reasonable answers—or impartiality—partiality to no particular answer except on the basis of reasonableness.

The corresponding vice, intellectual dishonesty, entails a disregard for knowing the truth. It can be characterized as close-mindedness—being closed to the consideration of some reasonable answers—or dogmatism—being committed to an answer with no regard for its reasonableness or the reasonableness of the alternatives.

Intellectual honesty does not by itself produce good reasoning. But it does put you in the correct frame of mind to evaluate all relevant arguments and to seek further evidence if need be—that is, to practice the virtues of critical reflection and empirical inquiry.

1.4.4 The Major Obstacles to Intellectual Honesty

Three of the biggest impediments to intellectual honesty are self-interest, cultural conditioning, and overconfidence.

Intellectual dishonesty often occurs when the desire to know the truth is overridden by self-interest. Wishful thinking is what we often call it. This was the problem in the case of the space shuttle Challenger. But many cases of self-interest aren’t nearly so dramatic. Suppose it is spring, the Monday after daylight-saving time has gone into effect. As always, you get into your car at 6:30 a.m. to drive to your early class. But today, because of the time change, you must turn on your headlights. By the time you get to school the sun is up. You go to class, and midway through the first lecture it hits you—you forgot to turn off your headlights! But with a full day of classes and your part-time job, you will have no chance to walk all the way back to the parking lot to turn them off. Your mind races. You squeeze out the thought that you can’t remember turning them off and tell yourself that you surely clicked them off instinctively. Yes, you reassure yourself, you turned them off. Your desire is not above all to know the truth about the question, Did I turn off my headlights?, but to arrive at your preferred answer. You succeed and don’t think of it again until late that night when you are wondering where you can find some jumper cables.

Another obstacle to intellectual honesty is cultural conditioning. It is usually easy for us to find examples of this in other cultures (or in other segments of our own culture), but much harder to find them in our own. Our own views are familiar, comfortable, and do not seem to call out for special scrutiny. They are ours, after all. Women are inferior. Slavery is acceptable. The prevailing religion is true. All of these have been clung to uncritically only because the believer’s training and environment make the beliefs seem so right.

Self-interest and cultural conditioning are not the only impediments to honesty. It sometimes is hindered by overconfidence in the power of good reasoning to deliver knowledge of the truth. If you are like most of us, you sometimes get the wrong answer, even when your reasoning is flawless. It is always possible that you are mistaken, and forgetting that possibility can be the first step toward close-mindedness and dogmatism.

Consider science, often held up as the paragon of good reasoning. Scientists have repeatedly and confidently offered their definitive answers to many questions, including, for example, How large is the universe? Note this partial record, measured in earth radii.

Size of Universe

| Scientist | Date | Universe in Earth Radii |

|---|---|---|

| Ptolemy | ad 150 | 20,000 |

| Al Farghani | 9th century | 20,110 |

| Al Battani | 13th century | 40,000 |

| Levi ben Gerson | 14th century | 159,651 billion |

| Copernicus | 1543 | 7,850,000 |

| Brahe | 1602 | 14,000 |

| Kepler | 1609 | 34,177,000 |

| Kepler | 1619 | 60,000,000 |

| Galileo | 1632 | 2,160 |

| Riccioli | 1651 | 200,000 |

| Huyghens | 1698 | 660,000,000 |

| Newton | 1728 | 20 billion |

| Herschel | 1785 | 10,000 billion |

| Shapley | 1920 | 1,000,000 billion |

| Current value | Now | 100,000 billion |

—Derek Gjertsen, Science and Philosophy

Science itself looks honest here—always willing to revise in the face of new evidence. But we are not talking about the intellectual virtue of disciplines (like science), but the intellectual virtue of human beings (like individual scientists, or you and me). The lesson is that even when good scientists reason well about the physical world, their conclusions are subject to revision in the face of additional evidence; and they can be guilty of a sort of dishonesty if they become overconfident in their conclusions. Surely many conclusions reached by nonscientists like you and me are at least as susceptible to revision.

Intellectual honesty requires that you be always aware of the possibility that you might be wrong. And the alternative to your current answer is not necessarily another answer. The alternative may be that there is, as yet, no good answer.

The good reasoner is critically reflective, empirically inquisitive, and intellectually honest.

Some Intellectual Virtues: Habits of Thinking That Are Conducive to Knowledge

- Critical reflection—asking what the arguments are for your beliefs and whether those arguments are sound, clear, and relevant.

- Empirical inquiry—seeking out new evidence from the world around you to better answer your questions.

- Intellectual honesty—wanting, above all, to know the truth about the questions you care about.

EXERCISES Chapter 1, set (c)

For the scenarios below, describe ways in which each of the intellectual virtues appears to be lacking.

- You take a course in an area that is new to you and work harder than you have ever worked in your life on the term paper. The professor returns it with a D+, commenting that you should come to his office to talk to him about how you can improve. Although he has provided copious notes in the margins, you do not even look at them, charging out of the classroom and complaining to your friends, “He’s been against me since the first day of class! I had no chance to do well on this paper!”

- Your new roommate is from another country and follows a religion you have never heard of. You treat your roommate’s observances of the religion with respect, but privately remain convinced that your religion is the right one. You have never really thought much about it, but it is what you have always been taught, and it just seems right to you. Surely your roommate is mistaken.

- Trofin Denisovich Lysenko had a stranglehold on Russian biology from 1934 to 1964. What he lacked in scientific talent, Lysenko more than made up for in political know-how. Early in his career, Lysenko hit upon the idea that winter wheat could be converted into spring wheat by exposing it to cold and then planting it in springtime. The seeds from that wheat, he believed, would not need to be converted into spring wheat; they would have already become spring wheat by virtue of inheriting the “vernal” characteristic acquired by the previous generation. But he had no good evidence that acquired characteristics could be transmitted to offspring, and the view flew in the face of modern biology. But Lysenko managed to convince Stalin, and later Kruschev, that only his view of biology conformed to Marxist political ideology. Through his influence, textbooks were altered and biologists who tried to do real biology were persecuted and imprisoned. Thus insulated from contrary evidence, Lysenko’s beliefs about biology were secure and his ambitions were realized. Soviet agriculture faced crisis after crisis during the middle years of the 20th century, but until Lysenko’s death in 1964, it was unable to benefit from the agricultural advances of modern biology.—Jeremy Bernstein, Experiencing Science

- Jake McDonald dreamed of getting rich. Although he had no money, he had a plan: find the right existing business, buy it with a loan from the seller, pay off the loan with income from the business, and sell franchises. He was sure he could make it happen; he was just sorry that his name had already been used.After a year of searching, he was confident he had found his ticket to riches right around the corner from his apartment. It was a pizza place with a difference. Aptly named Take and Bake Pizza, its made-to-order pizzas were unbaked. He was in love with it! Prices were lower because the business required less equipment and less space (no ovens) and needed fewer employees (no cooks). Customers would have a shorter wait for delivery and, since they would bake it at home, would never have to eat it cold. Best of all, the owner wanted to sell. And, well, Jake’s name did fit it so perfectly.He could hardly contain his enthusiasm. As he went to sleep every night, his mind was filled with images of Jake’s Take and Bake stores in mini-malls across America. True, the sketchy records the owner showed him suggested that cash flow was barely covering expenses, but that could be corrected with aggressive marketing.Jake’s girlfriend, however, was skeptical. There’s still a wait for the pizza while you bake it yourself, she pointed out. And don’t most people who call Domino’s want to avoid even the trouble of turning on the oven, properly preheating it, and listening for the timer? The real competition, she suggested, could be the grocery and convenience stores; they are surely capable of stocking fresh unbaked pizzas daily and selling them even cheaper than Take and Bake. And finally, she wondered, if the current income was barely covering expenses, how did Jake propose to pay for the marketing campaign?Jake ignored her and made the deal. After all, he had scored over 1500 on his SAT, and she hadn’t even gone to college. Six years later, while on the way home from his job as a cook at McDonald’s, Jake stopped off at one of the 7-Elevens she now owned to buy a fresh unbaked pizza for dinner.

- “Stepan Arkadyevich had not chosen his political opinions or his views—these political opinions and views had come to him of themselves—just as he did not choose the shapes of his hat and coat, but simply accepted those that were being worn. . . . If there was a reason for his preferring liberal to conservative views, which were held also by many of his circle, it arose not from his considering liberalism more rational, but from its being in closer accordance with his manner of life. The liberal party said that in Russia everything was wrong, and indeed Stepan Arkadyevich had many debts and was decidedly short of money. The liberal party said that marriage was an institution quite out of date, and that it stood in need of reconstruction, and indeed family life afforded Stepan Arkadyevich little gratification, and forced him into lying and hypocrisy, which were so repulsive to his nature. The liberal party said, or rather allowed it to be understood, that religion was only a curb to keep in check the barbarous classes of the people, and indeed Stepan Arkadyevich could not stand through even a short service without his legs aching, and could never make out what was the object of all the terrible and high-flown language about another world when life might be so very amusing in this world. . . . And so liberalism had become a habit of Stepan Arkadyevich.”—Leo Tolstoy, Anna Karenina

1.5 HOW THIS BOOK CAN HELP

You may already be pretty good at reasoning. You got through childhood and adolescence, which means that you successfully answered many critical questions, such as Where’s the food? and Where’s the shelter? You got through most of this introductory chapter; perhaps you even found some mistakes in it. But for something as valuable as good reasoning, pretty good should not be good enough. What can this book do to help you reason better?

At a minimum, it can draw your attention to things you already instinctively know about reasoning, thereby putting you in a better position to use that knowledge. Very few of the concepts in this book will be new to you. But many of them will get a name for the first time and will be explained in such a way that their significance for reasoning is clearer. Like the title character of Moliere’s Bourgeois Gentleman, who is amazed to learn that for most of his life he has “been speaking prose, and didn’t know a thing about it,” for most of your life you may have been reasoning according to certain guidelines without knowing what they were called or even being fully aware of them.

But this book should do more than that. It gradually unfolds a systematic approach to clarifying and evaluating arguments, with the focus on soundness, clarity, and relevance. And it contains many examples of real-life arguments on which you can practice this systematic approach, thus gaining a great deal of practical experience in following the book’s guidelines.

When I first learned to type, I was temporarily cursed with the habit of mentally typing out my every conversation. When students first work on these exercises, they sometimes find that they cannot read the newspaper or talk to a friend without mentally clarifying and evaluating every argument. But the curse is eventually lifted, and it is replaced with the blessing of better reasoning. The philosopher Gilbert Ryle, comparing formal logic to real-life reasoning in “Formal and Informal Logic,” notes:

Fighting in battle is markedly unlike parade-ground drill. . . . None the less the efficient and resourceful fighter is also the well-drilled soldier. . . . It is not the stereotyped motions of drill, but the standards of perfection of control, which are transmitted from the parade ground to the battlefield.

And management expert Peter Drucker tells of his boyhood piano teacher’s stern words: “You will never play Mozart the way Arthur Schnabel does, but there is no reason in the world why you should not play your scales the way he does.” You may never reason like Aristotle or Newton, but by applying yourself to these exercises you can expect to more fully develop the same fundamental habits of mind and to become a better reasoner for it.

1.6 SUMMARY OF CHAPTER ONE

Reasoning is the attempt to answer a question by thinking about reasons. Good reasoning requires having good reasons for what you believe, and good reasons can best be expressed in good arguments. So good arguments are crucially important to good reasoning.

An argument is a series of statements in which at least one of the statements is given as reason for belief in another. A good argument is an argument that is sound—that is, the premises are true and the conclusion follows logically from the premises—and one that is also relevant to the conversation and clear.

We don’t usually think by means of carefully constructed arguments, but by means of various quick-and-dirty shortcuts, or judgmental heuristics. For example, we tend to rely on the most vivid information, we tend to infer on the basis of similarity, and we strongly favor preexisting beliefs. These tendencies are not to be entirely discarded but are to be tempered by the cultivation of other habits—by the cultivation of intellectual virtues.

One important intellectual virtue is the virtue of critical reflection—the habit of asking (when both time and the significance of the question warrant it) what the argument is for each belief and whether that argument is sound, clear, and relevant. Another is empirical inquiry—the habit of seeking out evidence from the world around us. And a third virtue is intellectual honesty—the habit of wanting, above all, to know the truth about the questions we ask; this virtue enables us to express and evaluate arguments unencumbered. The good reasoner is critically reflective, inquisitive, and honest.

1.7 GUIDELINES FOR CHAPTER ONE

- Use good reasoning if you want to know the answers to the questions you care about.

- Look for the following four merits in any argument: true premises, good logic, conversational relevance, and clarity.

- To become a good reasoner, cultivate the intellectual virtues—that is, habits of thinking that are conducive to knowledge.

- To reason more successfully, cultivate the virtue of critical reflection—that is, develop the habit of asking what the arguments are for your beliefs and whether those arguments are sound, clear, and relevant.

- To find good answers to your questions, cultivate the virtue of empirical inquiry—that is, develop the habit of seeking out new evidence from the world around you.

- To lay the foundation for good reasoning, cultivate the virtue of intellectual honesty—that is, develop the habit of wanting, above all, to know the truth about the questions you care about.

- To enhance intellectual honesty, be especially wary of the influences of self-interest, cultural conditioning, and overconfidence.

1.8 GLOSSARY FOR CHAPTER ONE

Argument—a series of statements in which at least one of the statements is offered as reason to believe another.

Clear argument—an argument in which it is possible to tell whether the premises are true, whether the logic is good, and whether the argument is conversationally relevant.

Conclusion—the statement that reasons, or premises, are offered to support.

Conservation shortcut—preserving previously adopted beliefs as a shortcut in reasoning. This can be helpful but is not always supported by the evidence.

Conversationally relevant argument—an argument that is appropriate to the conversation, or the context, that gives rise to it; it does not miss the point or presuppose something that is in question in the conversation.

Critical reflection—asking what the arguments are for what you believe, and whether those arguments are sound, clear, and relevant.

Empirical inquiry—seeking out new evidence from the world around you to better answer your questions.

Good reasoning—the sort of thinking most likely to result in your having good reasons and, thus, the sort of thinking most likely to give you knowledge.

Intellectual honesty—wanting, above all, to know the truth about the questions you care about.

Intellectual virtues—habits of thinking that are conducive to knowledge by making it more likely that the answers you arrive at are well reasoned.

Logical argument—an argument in which the premises strongly support the conclusion—that is, the premises make it reasonable to believe the conclusion.

Premise—a statement offered as a reason to believe the conclusion of an argument.

Reasoning—the attempt to answer a question by thinking about reasons.

Reasons—whatever you depend on in support of what you believe, regardless of whether you consider your belief to be knowledge or mere opinion. Words that mean more or less the same thing are the following: premises, evidence, warrant, justification, basis, grounds, and rationale.

Shortcuts in reasoning—quick and practical ways of arriving at answers to your questions that do not involve organized arguments. More formally called judgmental heuristics. Heuristic is closely related to the word eureka, which is Greek for “I found it!” According to legend, Archimedes shouted “Eureka” as he ran naked through the streets of ancient Athens, having hit upon an important idea as he bathed.

Similarity shortcut—relying on a quickly noticed resemblance between the familiar and the unfamiliar as a shortcut in reasoning. This can be helpful, but is not always supported by the evidence. Also called the representativeness heuristic.

Sound argument—an argument that both is logical and has true premises.

True statement—a statement that corresponds to the world.

Unsound argument—an argument that has at least one false premise or is illogical (or both).

Vividness shortcut—relying on whatever information stands out most in your mind as a shortcut in reasoning. This can be helpful but is not always supported by the evidence. More formally called the availability heuristic.

CHAPTER DESCRIPTION

- Discusses criteria for a thesis statement, guiding idea, and purpose

Two Types of Essays