Domain IV: Culturally Responsive and Socially Just Relational Practices

CC12 Constructive Collaboration

Nurture constructive collaboration and egalitarian relationships with clients.

Recommended Reading

Collins, S. (2018). Culturally responsive and socially just relational practices:

Facilitating transformation through connection. In S. Collins (Ed.), Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: Re-shaping professional identity in counselling psychology (pp. 484–499). Counselling Concepts. https://counsellingconcepts.ca/

Core Competency 12 of the CRSJ counselling model (Collins, 2018) focuses attention on the importance of minimizing power differences to establishing an egalitarian relationship with clients from which it is possible to collaborate actively throughout the counselling process. The relational stance of egalitarianism and client-centred practice is grounded in feminist therapy (Brown, 2010). To work effectively with clients across cultural differences, it is important to create a working alliance characterized by collaboration and a focus on the co-construction of meaning. Paré (2013) used the constructive collaboration between counsellor and client to reinforce the importance of proactive and purposeful collaboration with clients to support attainment of their preferred outcomes. Learners are encouraged to avoid preconceived notions of cultural identities and social locations by co-constructing meaning with clients and supporting clients to engage in what narrative therapists label life-making or self-composition. A constructivist metatheoretical lens supports learners to create space for client expertise in their own lives (Paré, 2013; Brown, 2010). In this context, power is shared within the relationship, and resistance or alliance ruptures are conceptualized as relational hurdles not client problems (Paré & Sutherland, 2016). These ruptures may emerge from a lack of trust in the relationship, a breakdown in collaboration, or a power-over stance on the part of the counsellor.

CRSJ Counselling Key Concepts

The activities in this chapter are designed to support competency development related to the key concepts listed below. Click on the concepts in the table and you will be taken to the related activities, exercises, learning resources, or discussion prompts.

Alliance Ruptures

Preventing and mitigating alliance ruptures (Class discussion)

Consider the following client–counsellor story.

You are meeting a new client for the first time. You are in your third month of your practicum, and you are really excited to be mentored by a woman who has been practicing solution-focused therapy for over 20 years. You are about to meet a young woman named Aamira. You have “googled” her name, so you know there is a possibility she is Muslim. When you go to the waiting room, she is wearing a hijab and is accompanied by two other women who stand up to follow you into the counselling session. Take a moment to reflect on your honest reactions, cognitive and affective, to women wearing the hijab. You may be reflecting from a within group perspective as a Muslim or from an outsider perspective as a non-Muslim. Attend carefully to this positioning in your reflections.

Aamira has listed depression and anxiety as her presenting concern. She says that she is struggling to find meaning in her life. She is employed as an esthetician, although she has been working fewer hours over the last few months because of her state of exhaustion. She is accompanied by her sister and her first cousin. In the first session, you explore Aamira’s history of emotional distress, her medical history, her sources of social support, the stressors and challenges in her job and personal life, and the specific symptoms she is encountering. She is engaged but somewhat distant. You have a sense that you are not getting the whole picture from her, but it seems important to provide her with a sense of hope and expectancy about the counselling process to ensure that she returns for the next session. You invited her to consider the miracle question “Suppose tonight, while you slept, a miracle occurred. When you awake tomorrow, what might you notice that would tell you life had suddenly gotten better?” Aamira listens intently. She then turns to her companions and seems to discuss the question with them in Arabic. You ask if there is anything she or her companions want to clarify, but she shakes her head. She seem retiscent to respond, however, so you suggest that she think about this as a homework activity this week. You provide her with a workbook that your supervisor has created to guide her through the miracle question homework. You state that you look forward to seeing her next week, either with or without her companions.

Aamira shows up a few minutes late for her second session, and she doesn’t look you in the eye when she arrives. She appears to be on her own this time. You welcome her and ask a few questions about her week before checking in with her about her homework. She says that her week was fine and that her sister and cousin are waiting outside for her. She just wanted to return the workbook you gave her. You notice that she has not filled in the exercises. You can tell she is uncomfortable. You thank her and gently remind her that she is welcome to leave at any time, but you extend an invitation for her to talk with you about whatever is bothering her. She gets up and comes back a few minutes later with her two companions. One of them takes the chair directly facing you, and says “Why is there no Muslim counsellor here who can see Aamira? We make up the majority of people in this neighbourhood.”

Discuss together how you might respond to the challenge you were presented with in the second session. There appears to have been a rupture in the working alliance with Aamira, but the story has been left deliberately vague so that you can choose which direction you head in your contributions to the class discussion. You may want to review the Competencies for Addressing Spiritual and Religious Issues in Counseling put out by the Association for Spiritual, Ethical, and Religious Values in Counseling to support your conversation. Here are some prompts that may help to get the dialogue going.

- What assumptions have you made about Aamira’s statement that she is struggling to find meaning in her life? How might these assumptions reflect your own values or biases?

- What was your gut reaction to the first encounter with Aamira and her family? What elements of your value system (not necessarily cultural biases) may have been reflected in your responses?

- How might these values have influenced how you managed the first session with Aamira?

- How successful were you in establishing an egalitarian relationship and engaging Aamira in constructive collaboration?

- What are your cultural or other hypotheses about what happened in this story?

- What next steps might you take based on your learning in either this lesson or previously in the course?

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc12/#preventingruptures]

Co-Construction of Meaning/Language

High-context versus low-context communication styles (Large group activity)

Watch the following YouTube video about high-context and low-context communication styles.

Consider the relationship between communication styles and cultural values below (Zakaria, 2017). Be aware of the risk of stereotyping as you engage in this activity, remembering that personal cultural identities are constructed in ways that often blend and adapt cultural worldviews. Zakaria emphasized that cultural communication styles exist on a continuum of low to high context.

- High-context communication styles: A lot of unspoken information is implicitly transferred during communication; many things are left unsaid; and meaning is derived through cultural context, social location, and culture-specific interpersonal roles. The speaker’s behaviour, nonverbal cues, and word choice become very important, because a few words can communicate a complex message to other members of the same cultural group. In the context of cross-cultural communication important meaning can be lost. High-context styles tend to exist in cultures that hold collectivist values (e.g., interpersonal relationships, harmony, and consensus).

- Low-context communication styles: Most, if not all, information is exchanged explicitly through the specific words that are used, and rarely is anything implicit or hidden. The communication is more direct, succinct, and linear. Low-context styles tend to correspond to more individualistic cultures where autonomy, individual achievement, and linear logic are valued.

Next, six individuals volunteer to act out three Short scenarios that demonstrate within-culture and cross-cultural, high and low-context communication. Introduce each scenario sequentially. Present the content in italics as if it is your self-talk (using a softer or different voice or other nonverbal indicators). Based on the three short dialogues, work together to guess the context of each individual in the scenario and the match or mis-match between.

Alternatively, view together the following video. Pause the video after each scene to match up the individuals with high- or low-context communication styles.

Discuss the implications for client-counsellor communication and the co-construction of meaning.

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc12/#highcontext]

Counselling Style

Is it OK to impose our values related to collaboration on clients? (Class discussion)

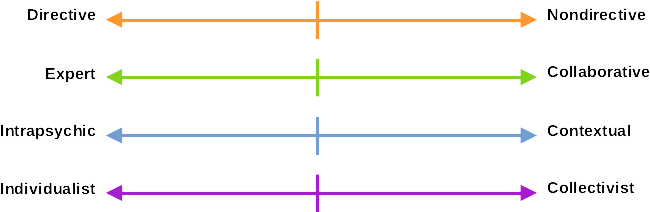

Reflect on your own emergent theory, theories, or integrative models of counselling as well as your personality and preferred ways of interacting with clients. Then position yourself on the continua below, by imagining where you would place the vertical line on each on. Make your choices as if the client had no influence on your style. Now consider the following situation.

Now consider the following situation.

Phoebe comes to the university counselling centre for a single-session career orientation that is part of career week at the university. She comes with very specific questions about how to choose the best option for her career based on the expectations of her parents, who still live in Hong Kong, and what she has gathered from her first semester in Canada. She has also done her research about you and knows that you have considerable expertise in career decision-making. She assumes this means you will help her make a decision about which educational path to following before she registers in her next semester courses. She is not interested in talking about her perspectives, dreams, or preferences. She has been told by her parents to choose the most lucrative path with a high probability of immediate employment upon graduation.

Engage in a critical discussion with your peers about how to balance congruence of your own theory and counselling style, the principles of CRSJ counselling, and responsiveness to the preferences and needs of a particular client, using Phoebe’s expectations as a starting point.

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc12/#collaboration]

Cultural Countertransference

Using power analysis to address cultural countertransference

[Contributed by Cristelle Audet]

Think back to a time when a client suggested that you may not be able to relate to them or to their experiences as a result of an age, ethnicity, gender, religious, or other cultural difference. If you are not yet seeing clients, then conjure up a vivid image in your mind of what this might be like and how you might react, emotionally and cognitively.

Conduct your own power analysis, assessing your personal and professional power, a client’s power, and institutional power. Follow the steps in power analysis (provided in a later learning activity).

- What aspects of power risk being enacted through countertransference?

- How might you be able to utilize your observations in a way that has therapeutic value for the client?

- What do you conclude in terms of finding and taking a culturally sensitive way forward?

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc12/#poweranalysis]

Meaning-Making

Each person should draw a table that has five rows and three columns. At the top of each column, write down a context in which you might encounter a particular word, for example: Beverley Hills, rural Somalia, or the space shuttle. Please do not share your ideas about context with others.

When everyone has their table constructed, play the following audio. As you hear each word, jot down the meanings you associate with that word for each of your three contexts. Don’t overthink; engage in quick free association.

In pairs or as a small group, share some of the meanings you came up for each word.

- What were the similarities and differences in your lists?

- What meaning do you make of these differences?

- What are the implications for meaning-making in counselling?

Paré (2013) refers to the hermeneutic circle in counselling as the process of navigating back and forth between foreground and background, part and whole, to broaden our understanding of meaning in context. Discuss together how you might apply this principle in your work with clients.

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc12/#whatsin]

Form teams of four people; then split into two pairs. Each pair should complete the following tasks (5 minutes).

- Decide on a mini-culture (e.g., stamp collectors, mud wrestlers, eco-travellers).

- Make up some nonverbal ways of expressing yourselves which are (a) unique to your mini-culture and (b) different than common nonverbal expressions. Draw on tone of voice, body language, facial expressions, gestures, and so on.

Next, come back together as teams of four to complete the following steps.

- One set of partners interview the other set of partners (3-5 minutes each) on a particular topic, for example:

- The challenge of poverty in Canada

- The glass ceiling – a myth or reality

- Aging populations and the health care system

- The partners being interviewed will use their agreed upon nonverbals, as if they are speaking from their new mini-culture.

- Switch roles and repeat.

Debrief with the whole class.

- Speakers: What was it like to change the default setting on some established nonverbals?

- Interviewers: What was it like to make sense of the others’ experience given their unfamiliar nonverbals?

- What practice principles can you carry forward from this exercise to support cultural responsivity in counselling practice?

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc12/#inventingnonverbal]

Values Differences/Conflicts

Resolving counsellor–client values conflicts (Partner activity)

A variety of values differences and conflicts may emerge, directly or indirectly, in your work with clients. Select at least two of the videos below, imagining yourself in the role of a counsellor with this individual. Create two columns on a piece of paper and label them “My values” and “Client values.” As you view each video, list the values you observe both in your own responses and the choices and perspectives of the “clients.”

It can be challenging to discern specific values that undergird our thoughts, emotions, and behaviours. As you compare and contrast your lists with your partner, use this as an opportunity to practice becoming comfortable questioning each other at the level of personal values.

Strong Language Warning: If you selected the video by Dan Savage above, you may have reacted to his choice of strong and explicit language. If you didn’t watch this video, you might want to watch a few minutes to reflect on your own reactions. I deliberately included this video, because clients’ ways of expressing themselves may also be a place where your values rub up against each other.

Once you have created your two lists of values, complete the following steps:

- Highlight the commonalities you observe across the two lists of values.

- Highlight, in a different colour, any differences you observe. Be as honest as you can in identifying places where your values diverge from these potential clients’ values.

- Return to the Professional Values Principles from Core Competency 9 (MS Word version), and consider how these principles might be helpful in helping you work through values conflicts that emerge in your work with clients.

- What other strategies might you employ for addressing values conflicts in the client–counsellor relationship?

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc12/#resolvingconflicts]

Values Imposition

Place yourself into the following scenario.

I recall an encounter with a client a few years ago who used the word fuck in every sentence, sometimes more than once. Although I am not normally reactive to anyone’s choice of how they want to express themselves, I found myself feeling a bit uncomfortable because of the loudness of his voice. I was aware of the possibility that a colleague might overhear him. In that moment, I had to step back and ask myself the following questions: Is this reaction I’m having really about him or about me? What message am I sending about his freedom of expression, the safety of this space, my stance of nonjudgment, and so on, by asking him to change his behaviour? What effect might that have on our working alliance? What message is he communicating to me through the strength of his language? These self-reflective questions helped me to check my own feelings and to acknowledge that my reaction was about me being embarrassed, not about him doing something that was inherently problematic or wrong. From within his way of experiencing the world and his social context, his language use reflected a common way of expressing the depth of feeling associated with his experiences.

Fortunately, I did not shut him down from expressing his strength of emotion, and my position of nonjudgment and lack of reactivity helped to build our working alliance. After a couple of sessions, his communication style shifted, perhaps because he realized I was hearing him without the consistent strong language to emphasize his emotion or perhaps he had another reason for the change in style. The point is that we must continuously be aware and reflective about our own values and cautious not to impose them on our clients.

Drawing on this scenario, work through the following questions for reflection:

- In what ways might you proactively address the potential for values conflicts with clients in order to avoid imposing your values on them?

- Under what rare conditions might it be important to address directly a values conflict with a client? In other words, what client values might you be unable to simply treat with respect and nonjudgment?

- How would you discern when it was important to address counsellor–client values differences directly with a client (versus addressing these as part of your own continued competency development)?

- When client values appear to impede their health and well-being, how might you invite clients to consider their own values’ positioning as part of the counselling process?

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc12/#reallytheproblem]

References

Brown, L. S. (2010). Feminist therapy. American Psychological Association.

Collins, S. (2018). Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: Re-shaping professional identity in counselling psychology. Counselling Concepts. https://counsellingconcepts.ca/

Paré, D. (2013). The practice of collaborative counseling & psychotherapy: Developing skills in culturally mindful counselling. Sage.

Paré, D., & Sutherland, O. (2016). Re-thinking best practice: Centring the client in determining what works in therapy. In N. Gazzola, M. Buchanan, O. Sutherland, & S. Nuttgens (Eds.), Handbook of Counselling and Psychotherapy in Canada (pp. 181-202). Canadian Counselling and Psychotherapy Association.

Zakaria, N. (2017). Emergent patterns of switching behaviors and intercultural communication styles of global virtual teams during distributed decision making. Journal of International Management, 23(4), 350–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intman.2016.09.002