Domain IV: Culturally Responsive and Socially Just Relational Practices

CC10 Transformative Relationship

Optimize the transformative nature of the client–counsellor relationship.

Recommended Reading

Collins, S. (2018). Culturally responsive and socially just relational practices:

Facilitating transformation through connection. In S. Collins (Ed.), Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: Re-shaping professional identity in counselling psychology (pp. 441–472). Counselling Concepts. https://counsellingconcepts.ca/

Core Competency 10 in the CRSJ counselling model (Collins, 2018) focuses on the nature of the client–counsellor relationship and the centrality of this relationship to the overall counselling process. Positioning counselling as a relational practice focuses attention on the ways in which interpersonal, social, and systemic oppression results in disconnection from self, others, and community (Lenz, 2016; Singh & Moss, 2016) and paves the path for transformative and decolonizing therapeutic relationships that open the door to healing and connection (Brown, 2010; Singh & Moss, 2016). The quality of the counsellor–client relationship is gauged by the evolution of mutual cultural empathy, in which both counsellor and client are amenable to change (Jean Baker Miller Training Institute, 2017; Singh & Moss, 2016). Counsellors develop cultural empathy towards clients as they engage in cultural inquiry with clients. By also sharing elements of their own cultural identities, a sense of mutual cultural empathy also emerges. In effect, the counsellor communicates not only a willingness to see the client, but also an openness to being affected by their stories and lived experiences. Paré (2013) centralized the ethic of care as a relational orientation to practice in which the ways of being of the counsellor are responsive to what is helpful to the particular client in the moment. Counsellor credibility then derives from the respect, transparency, and trust within the relationship, rather than from expertise or power (Brown, 2010; Paré, 2013; Singh & Moss, 2016). It is also important to consider how we, as service providers, open or close the door to relationships with potential clients through the ways in which mental health services are positioned and provided within communities.

CRSJ Counselling Key Concepts

The activities in this chapter are designed to support competency development related to the key concepts listed below. Click on the concepts in the table and you will be taken to the related activities, exercises, learning resources, or discussion prompts.

Bearing Witness

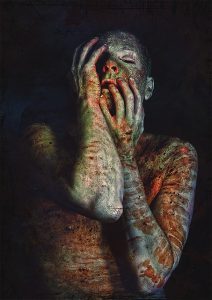

Take a moment to sit quietly with the image on the left. Paré (2013) argued that compassion is a way of being that involves a willingness to open to another person’s suffering as part of our shared humanity. As you consider the concept of bearing witness, discuss the notion of suffering as a core human experience and a foundation for connection and trust-building between counsellor and client. From a social justice perspective, how might your position of relative privilege or marginalization impact your ability to connect or empathize with clients’ suffering? How willing and able are you to be present to another person’s pain? How might you enhance your capacity for bearing witness?

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc10/#suffering]

Compassion Fatigue

Countering compassion fatigue with self-care (Self-study)

[Contributed by Karen Cook]

Engaging in our multiple roles as counsellors from a relational position of compassion and care can be emotionally, psychologically, and physically taxing. What happens when counsellors, community members, and other care companions are stretched past the limits of their own compassion? For this learning activity, I invite you to create two Wordles (Use this free Word Cloud Generator, or choose a different tool if you like).

- The first word cloud should contain words that you associate with the term compassion fatigue. Create this before you read further about how compassion fatigue is defined in the counselling literature. Choose colour and design that speaks to you of your emotional reaction to this term.

- Then create a second word cloud that depicts self-care and other strategies to prevent or counteract compassion fatigue. You may want to search the Internet for some ideas.

- Compare your two wordles, and choose one strategy you can begin to implement this week.

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc10/#countering]

Counsellors who work with refugees who have endured conditions of torture or other forms of extreme violence, for example, are at risk of being vicariously traumatized through their counselling experiences. There are also many other contexts in which counsellors develop what is now referred to as compassion fatigue through persistent exposure to emotionally demanding client situations and contexts.

There are times when you may be tempted to protect yourself by leaning out rather than leaning in to the relationship with your client. Think of a specific example in a movie, novel, news report, or a personal or professional encounter when you felt yourself pull away from another person’s emotion or story. Reflect on that pulling away response—emotionally, cognitively, behaviourally—then discuss the following questions.

- What are you most afraid of in terms of working with clients who have experienced violence, torture, or other forms of trauma?

- What is most likely to trigger a leaning out response in you?

Work with your peers to come up with a list of proactive measures to minimize the risk of compassion fatigue (or the related experiences of vicarious traumatization and burnout) and to support a leaning in stance?

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc10/#leaning]

Connection‒Disconnection

Brené Brown is a professor at the University of Houston who identifies as a research and storyteller on the topics of courage, vulnerability, shame, and empathy. As a foundation for the class discussion, watch this 20 minute TED talk on the power of vulnerability.

In this video, Brené asserts that the emotion of shame and the belief that we are not worthy are significant barriers to connection for many people. Reflect first on how this assertion rings true, or not, with your own lived experience. Then, engage in a dialogue about the implications of this assertion for working with clients whose interpersonal experiences of connection–disconnection may be complicated by the layering of vulnerabilities related to the marginalization and relative social locations of certain people or peoples within society. What lessons might you carry forward for facilitating connection with your clients and supporting them to build connections with others?

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc10/#shame]

Cultural Empathy

Barack Obama on building a culture of empathy (Partner activity)

A counsellor’s ability to understand and communicate respect for client cultural experiences and worldview are central to building an effective and culturally responsive working alliance with clients. Barack Obama has spoken repeatedly on the topic of empathy. Enter the search term “Barack Obama Talking About the Importance of Empathy” in YouTube and choose several short clips to review. Attend to both the challenges to developing empathy he describes and his perspectives on the importance of empathy.

Based on your understanding of the concept of cultural empathy and your reflections on Obama’s wise words, identify (a) the steps that you might take to develop cultural empathy for a client (b) the means you might draw upon to demonstrate cultural empathy to a client. Share your ideas with one other classmate. What did you learn from reading the perspective of your peer? How were your perspectives similar or different? What does that tell you about the concept or application of cultural empathy?

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc10/#obama]

Flexing your cultural empathy muscles: The lived experiences of working-class and poverty class people (Self-study)

[Contributed by Fisher Lavell]

If you come from a middle-class background, it is often difficult to relate to the worldview and lived experiences of people from working-class or poverty-class backgrounds. The purpose of this activity is to help you to connect with these folks and strengthen your cultural empathy muscles.

- Think about a time in your life when you felt profoundly powerless and judged.

- Get in touch with the feelings you had, and try to put names to a bunch of those feelings (e.g., shame, guilt, embarrassment, frustration, hopelessness).

- Now, hold on to those feelings for a while, as you imagine going through one whole day.

- Plan out that day.

- What time would you get up if you felt that way?

- What would you do if you felt that way?

- What would you eat if you felt that way?

- Who would you want to be around?

- What would you do in order to feel better?

When you have completed this reflection, take a deep breath and clear your mind. And say a prayer of thanks, if you pray, and if you do not, just sit for another minute and feel grateful.

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc10/#empathymuscles]

Mutual Cultural Empathy

The concept of mutual cultural empathy derives from relational-cultural theory (RCT, Jean Baker Miller Training Institute). One of the defining features of RCT is that empathy and other core relational processes are shaped by an expectation that both counsellor and client are transformed in some way through the counselling relationship. Think of a recent conversation you have had, with anyone in your life, that you would label as transformative for both of you. What risks, benefits, or challenges can you see as you translate the concept of mutuality into counselling practice?

It is easier to picture how this process of mutual cultural empathy will evolve with a client you like and with whom you find it easy to relate. What about Joe, Raphael, Angel, or Chien-Shiung in the client scenarios below? How easy would it be to develop mutual cultural empathy?

| Joe comes to counselling because he is court-mandated to attend anger management sessions. He has a history of aggressive behaviour towards female partners and, most recently, pulled a knife on his current commonlaw partner. Joe’s first question is what he has to do to get the court off of his back. He responds to your questions with yes or no answers wherever possible and is watching the clock for most of the session. You can sense your frustration building as Joe continues to deflect responsibility for his actions. He holds firm to the belief that his partner provokes him and is, at least, equally responsible for the mess in which he currently finds himself. |

| Rafael is working as a drug dealer at a fairly high level in your local community. He has come for counselling to deal with his frustration with certain people who work for him. He also expresses his concerns about getting caught by the police, and he wants to talk about ways that he can manage his own life and his way of dealing with issues that arise to help him stay clear of the police and to avoid drawing attention to himself. He talks about experiences in the past where his reactions have made situations worse for himself and for others, but he hasn’t been able to find a way to control those reactions. He sees them as mostly automatic responses that have to do with his history and upbringing. |

| Angel refers to herself as a dyke. She has a strong presence physically and interpersonally. She shakes your hand firmly and begins swearing the moment she sits down. You notice she has a motorbike helmet with her. She is in her late-sixties, and she has recently been told that she has terminal cancer. She has refused treatment and is working with a physician who provides medical assistance in dying. She wants to plan a big going out party at which she will terminate her life. She refers jokingly to preparing her speech for Jesus so she can give him a piece of her mind when she gets to the other side. However, she can’t seem to get her current partner onside with the idea. |

| Chien-Shiung has come to counselling through an employee assistance program. She has been off work on stress leave for several months. She describes her supervisor as overbearing and unfair. She gives a couple of examples of work situations in which she chose not to do things the way her supervisor requested, because Chien-Shiung believed she knew better. She then reacted strongly when the supervisor questioned her work and asked her to consider a different approach. She says she doesn’t know if she will come back for counselling, because she told the intake worker those examples already and she is frustrated that you are wasting her time by asking her the same questions. |

Choose the hypothetical client (Joe, Rafael, Angel, or Chien-Shiung) you are least drawn toward. Work with your peers to generate ideas about how the principle of mutual cultural empathy might apply to working with the client. What barriers within yourself might you need to overcome? What commonalties, points of connection, or windows to mutuality might you draw on to facilitate the development of cultural empathy?

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc10/#whatif]

Respect for Dignity

Write a paragraph about how you define respect for dignity. Write in a descriptive way that operationalizes this term (i.e., makes transparent the behaviours that others would observe when you actively honour another person’s dignity). Then watch the video below by Vikki Reynolds as she defines what dignity means in her work with her clients who are often marginalized in society.

© Center for Response Based Practice [VanBC] (2017, April 19)

Note the elements of Vikki’s perspective that resonate with you, and revise your definition as appropriate. Test out the efficacy of your behavioural principles by applying them in an interaction with a colleague or friend. Then invite feedback on their experience of dignity in this conversation.

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc10/#ondignity]

Safety/Cultural Safety

Consider the explanation of cultural safety so eloquently expressed in this video from Northern Health, BC.

© Northern Health BC (2017, February 14)

Reflect on aspects of your personal cultural identity that might leave you feeling unsafe in certain health care settings. Then imagine what it would be like, in your most vulnerable moments, to experience marginalization and discrimination because of other aspects of your identity. Identify two specific intentions for creating cultural safety for your clients, being as specific as possible.

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc10/#feelsafe]

Self-Disclosure

To disclose or not to disclose (Self-study)

[Contributed by Cristelle Audet]

There are two forms of self-disclosure: (a) immediate, which involves sharing what is happening for you, emotionally or cognitively, in the moment with clients; and (b) nonimmediate, in which involves revealing personal information that might support relationship-building or demonstrate cultural empathy. In my work with clients, I self-disclose in both ways, as appropriate, sharing some of my own life experiences and decisions as well as some of the elements that define me as as cultural being or position my social location.

- What might be some of the risks of such a disclosure? What might be therapeutically valuable about such a disclosure? On what do you base your assessment of those risks and benefits?

- Has a client ever asked directly about your age or other aspects of your cultural identities? What might be a culturally empathic way of responding? What makes it so?

- Make a decision tree or map for decision-making regarding counsellor self-disclosure that includes an analysis of cultural considerations, power and privilege, and other constructs presented in this chapter. Reassess your map with each new disclosure experience. What has changed and why?

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc10/#todisclose]

Underutilization of Services

As a class, choose a country with which none of you are familiar (the more unlike your collective experiences the better). Do a bit of research on that country—consider dividing up the task to access a range of information on language, customs, religion, cultural diversity, economy, politics, human rights, and so on. (You are not writing a paper; just gather relevant basic content!)

Next, imagine yourselves as a group of new immigrants accessing services at a counselling centre in a major city in that country. Discuss your service needs, considering the following (as examples):

- What barriers are you facing? What would keep you from accessing the services being offered?

- What aspects of your cultural identities are supported, invisible, threatened?

- What cultural norms, practices, or roles fit or don’t fit?

- How do your beliefs about health and healing reflect or contrast with those of the agency?

- What delights you? What frightens you? What are you curious about?

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc11/#walking]

Ways of Being

Carefully consider the thesis statement Hanna Yusuf argues in the following YouTube video: The hijab resists the commercial imperatives that support consumer culture . . . the liberation lies in the choice. Attend to your immediate reactions to this assertion, particularly any inclination towards making judgements based on uncritical assumptions about women wearing the hijab. Then watch this YouTube video in which Hanna supports her assertion.

Reflect on the following questions to dig a little deeper into your own values and beliefs.

- What values-based assumptions did you hold, before listening to this video, about women wearing a hijab?

- How does framing the argument about the hijab in this way alter your perspective, or not?

- What are the implications for insider and outsider judgments about the meaning of cultural practices or symbols?

- What feminist or CRSJ counselling principles would mitigate counsellor cultural misinterpretations or misguided value judgments and support each woman to self-define their personal cultural identities?

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc10/#nonjudgement]

References

Brown, L. S. (2010). Feminist therapy. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Collins, S. (2018). Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: Re-shaping professional identity in counselling psychology. Counselling Concepts. https://counsellingconcepts.ca/

Jean Baker Miller Training Institute. (2017). The development of relational-cultural theory. https://www.jbmti.org/Our-Work/the-development-of-relational-cultural-theory

Lenz, A. S. (2016). Relational-cultural theory: Fostering the growth of a paradigm through empirical research. Journal of Counseling and Development, 94(4), 415-428. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12100

Paré, D. (2013). The practice of collaborative counseling & psychotherapy: Developing skills in culturally mindful counselling. Sage.

Singh, A. A., & Moss, L. (2016). Using relational-cultural theory in LGBTQQ counseling: Addressing heterosexism and enhancing relational competencies. Journal of Counseling and Development, 94(4), 398-404. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12098