Domain II: Challenge Social Injustices, and Critique Their Impact on Client–Counsellor Social Locations

CC5 Power and Privilege

Assess critically the impact of power and privilege on client–counsellor social locations.

Recommended Reading

Collins, S. (2018). The impact of social injustice: Client–counsellor social locations. In S. Collins (Ed.), Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: Re-shaping professional identity in counselling psychology (pp. 210–239). Counselling Concepts. https://counsellingconcepts.ca/

The fifth core competency in the CRSJ counselling model points to the importance of attending to the ways in which power and privilege play out in counselling. Ratts and colleagues (2015, 2016) reinforced the importance of careful attention to issues of relative privilege–marginalization between counsellor and client and the need for careful attention to power dynamics that emerge on the basis of client and counsellor cultural identities and social locations. In the context of counsellor education, these power dynamics must also be addressed and modeled for students in the context of teaching, supervision, research, and mentorship (Arthur & Collins, 2016; 2107). In the CRSJ counselling model, I position instructors, supervisors, and students all as learners. I encourage these learners to embrace a postmodern and social constructivist stance by honouring multiple realities, contextualizing experience, and emphasizing the social construction of meaning (Galbin, 2014; Gergen, 2015). I encourage learners to recognize their own sociocultural embeddedness and to consider the ways in which their cultural assumptions may be biased through internalization of dominant sociocultural narratives and discourses.

CRSJ Counselling Key Concepts

The activities in this chapter are designed to support competency development related to the key concepts listed below. Click on the concepts in the table and you will be taken to the related activities, exercises, learning resources, or discussion prompts.

Cultural Assumptions/Biases

Internalized images of ethnicity (Self-study)

[Adapted from contribution by Monica Justin]

Complete the Internalized images of ethnicity table (MS Word version) to explore the messages you have internalized from your family, community, and society about different ethnic and racial groups. You may find it useful to choose two specific ethnic cultures to focus on: one that you are quite familiar with and one to which you have had less exposure. Consider the following questions for reflection:

- How conscious or unconscious are you of these assumptions or biases as you interact with others?

- What are the implications of these internalized images for your first impressions of clients you encounter?

- How might you continue to bring these images into conscious awareness to challenge them and mitigate against imposing assumptions or biases on clients?

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc5/#internalizedimages]

Cultural Norms

What if same-sex relationships were the norm? (Self-study or large group activity)

This guided visualization can be used as a consciousness-raising exercise, individually or in a group.

- Create a quiet and comfortable environment. Once you are comfortable, we invite you to participate in a guided visualization using the audio recording below.

- Once you have experienced the visualization, respond to the following prompts for self-reflection:

- What are your initial thoughts and feelings as you reflect on this visualization?

- What are the specific heteronormative discourses reflected in this visualization?

- Think about your clients or potential clients. Which ones might live in a world similar to this one? What might their concerns be in coming to see you as a counsellor?

- What privileges might a heterosexual counsellor have that could get in the way of understanding the experience of a client of nondominant sexualities?

- What might counsellors of nondominant sexualities have to attend to in working with clients who hold heteronormative privilege?

- How might you mitigate or address the privilege and power that comes with certain aspects of your own cultural identities?

- This guided visualization is deliberately dated (from a Canadian perspective) to reinforce gains in recognition of nondominant sexualities over time.

- Take a moment to reflect critically on recent news events or to browse online news sites from other countries. What do you discover?

- What current trends, nationally and internationally, might threaten the rights of 2SLGBTQIA+ people in Canada?

- How might 2SLGBTQIA+ clients coming from other countries struggle with both ongoing heteronormativity in Canada and the dramatic contrast in human rights compared to their countries of origin?

Feel free to print yourself a PDF copy of the Guided Visualization for personal or professional use.

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc5/#whatif]

What if androgyny and gender fluidity were the norm? (Small group activity)

Listen to the What if same-sex relationships were the norm? guided visualization again. In either a face-to-face process or online as a shared wiki, work together to co-create a similar reflective tool to illustrate what it might be like to live in a world where androgyny and gender fluidity are the norm. Imagine what it might be like for those rare individuals who see themselves as exclusively male or female at their core. Be respectful in editing the work of other students and find ways to integrate your ideas into the flow of the emergent guided visualization.

- What are the implications for what you assume to be “normal” in terms of your interactions with clients?

- How might these normative biases lead you to engage in unintentional oppression and microaggressions?

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc5/#whatifandrogyny]

Dominant Discourses

Men are . . . Women are . . . (Partner activity)

[Adapted from the contribution by Vivian Lalande and Ann Laverty]

Take a blank page and create two columns, one titled “Men are . . .” and one titled “Women are . . .” Reflect on your family norms, your worldview, your cultural community, and how you were raised as a child. Complete each sentence with a phrase or word, going back and forth between the two columns, until you have a range of descriptors for each gender. Be as honest and spontaneous as you can, building the list until you run out of descriptors on either side.

Obviously, neither column reflects the lived experience or gender expression of all women and all men. Take some time to reflect with your partner on the emergent stereotypes and reflections of your gender role socialization by addressing the following questions:

- Where do these messages come from?

- What examples can you think of that disprove these messages?

- How do we learn these kinds of biases, and how do biases develop into stereotypes?

- How do others around you make these assumptions at home, at work, or at school?

- How might these beliefs, when they carry over into the counselling relationship and process, affect both client and counsellor?

Next, choose an ethnic, religious, or other cultural group with which you are not very familiar. Create a new page and write at the top, for example: “Muslim men are . . .” and “Muslim women are . . .” Follow the same process to identify descriptors in both columns. Try not to self-censor, because being honest about preconceptions is the first step in challenging and shifting potentially biased assumptions.

Compare your lists with your partner to see what additional items they were able to identify. Reflect on your list and consider the implications in term of both gender role socialization and cultural stereotypes. How might you avoid bringing even these subtle biases into your relationships with clients?

Finally, consider what it might be like to navigate these stereotypes if you identify with neither or both male and female genders. It is important to continue to challenge and problematize the underlying assumption that there are only two genders.

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc5/#menare]

[Adapted from contribution by Vivian Lalande and Ann Laverty]

Gender can be used to organize and structure situations and experiences; for example, assuming boys will prefer active experiences and girls will prefer passive activities may result in situations where girls are not offered the opportunity to engage in active experiences.

The Men are . . . women are . . . learning activity was intended to illustrate how we tend to assume differences or opposites between males and femals, which may be amplified by religious or other cultural worldviews. Language maintains and creates gender assumptions. For example, in some families, mothers “look after” their children while fathers “babysit” their children or certain domestic activities are referred to as “women’s work.” On a sheet of paper, brainstorm a list of expression that reflect the different gendered meanings or expectations we hold for males and females. Examples:

- Boys are rough and physical—Girls are tomboys.

- Men have stags—Women have showers.

- Male executives are strategic and assertive—Female executives are manipulative and aggressive.

Be sure to attend to cultural diversity in your comparisons by including gender assumptions you may make about those who differ from you in other ways.

Finally, gender is both a noun and a verb, in that we gender situations; for example, we might shake hands with a man, but hug a woman. In what other ways might counsellors tend to gender by acting or speaking in gendered ways? Think of ways that our counselling relationships and processes may be gendered. Reflect on how this gendering might impact clients who clearly identify as male or female and the barriers this might create for clients who do not comply with this false binary around gender (e.g., transgender, intersex).

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc5/#gendering]

Marginalization

Think of a person you love and feel protective towards (e.g., a child, an aging parent, a struggling friend). Conger up an image of that person or look at a picture of them, along with the emotions you feel toward them. Then, consider the following definition of marginalization.

- Relegated to a position of powerlessness;

- Deemed unimportant or without value;

- Treated as insignificant or peripheral; and

- Excluded or disadvantaged.

Imagine what it would be like to witness that special person in your life as they experience marginalization within their family, at school, at work, in their community, or at the hands of strangers. Stay present to your emotional, cognitive, and visceral reactions.

Try to hold onto these reactions as you now focus on a person or peoples who are marginalized in society. How might this transfer of mind, body, heart reactions enhance your capacity for empathy and compassion?

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc5/#personalizingmarginalization]

Othering

Complete the following quiz to increase your understanding of the thinking patterns that often support a process of othering. The quiz is intended as a creative way for you to identify and challenge thinking patterns that might make you more vulnerable to engaging in othering. You may want to try the quiz a number of times to consider carefully the subtle ways in which othering can creep into anyone’s thinking.

Once you have completed the othering quiz, reflect critically on your experience drawing on the following questions.

- What stood out for you from the cognitive misconceptions reflected in this quiz?

- What did you learn about your own tendency to think in certain ways?

- What are the implications for how you might inadvertently engage in othering?

- How might your insights from this quiz assist you in challenging your tendencies towards othering?

- What connections do you make between what you learned from this activity and the risks of dignitary harm, including appraisal versus recognition respect?

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc5/#thinkingpatterns]

Campaigning against othering (Small group activity)

[Contributed by Cristelle Audet]

In your small group, complete the following tasks:

- Identify a social identity or issue wherein othering is readily witnessed in social interactions, communities, the media, or other locations.

- Describe what othering has come to look like in that context, what helps perpetuate othering, and in what ways othering might contribute to oppression.

- Using these observations as allies to help you identify when oppressive discourse is unfolding, in what ways can you prepare yourself to respond to oppressive discourse in the moment on an interpersonal level?

- Devise a campaign geared to addressing the issue you identified above. What would it entail, and how might you carry it out? Commit to your plan by sharing it with a supportive peer or colleague. Which other allies could you seek out to walk alongside you in this effort?

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc5/#campaigning]

Privilege

What is privilege? (Large group activity + Class discussion)

Watch the YouTube video, What is privilege? Attend carefully to your emotional response to the separation of the participants along lines of privilege.

© As/Is (2014, July 15)

Face-to-Face setting

Line up students with enough space in front of and behind each person for them to step forward and backward easily. Read the Privilege walk (face-to-face) questions, and invite each participant to respond according to their own lived experiences, taking either one step forward or one step back. Pause at the end of the exercise, and invite participants to reflect on their relative positioning.

Online course

Assign 20 privilege points to each student in the course (participants may find it useful to place 20 coins or poker chips in front of them to start). Next, students should individually their way through each question in the Privilege Walk activity, either gaining a privilege point (coin or chip) or losing a point with each question. Choose either the audio or PDF version of the privilege walk questions below.

Each student should then post their final number of points (coins) as a starting place for discussion.

Face-to-face or online discussion

Consider some or all of the following questions in debriefing this exercise with participants.

- What are your emotional and cognitive reactions to your relative position of privilege or marginalization within the class?

- Imagine that you ended up in a different relative position; how might your reactions have differed?

- How might your relative position of privilege change if you were in a different group of people? What are the implications of this for working with a range of clients from diverse cultural backgrounds and social locations?

- What might it be like for clients with a relatively low, or a relatively high, position of privilege in society to encounter you as their therapist?

- What might it be like for clients who have a sense of relative marginalization to be invited into a collaborative counselling relationship?

- How might you mitigate the effects of privilege in the counselling process?

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc5/#whatisprivilege]

Each of us experiences relative privilege and marginalization along various dimensions of our cultural identities (e.g., gender, ethnicity, sexuality, ability). Share one aspect of your privilege to which you have not given much thought until now. If possible share a photo or other image to bring this sense of privilege to life for others.

It is unlikely that everyone in your community, city, region, or country will ever attain that level of privilege. How do you feel about giving up (or lessening) your privilege in this area? What might that look like in practical terms? Engage in a debate with your peers by arguing one of the following positions:

- Lessening the privilege we hold in some areas has the potential to foster equity and social justice?

- Lessening the privilege we hold in some areas is very unlikely to foster equity and social justice?

Toward the end of the conversation, once you have fully explored both statements, identify one specific and concrete implication this exercise could have for your relationships and work with clients.

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc5/#lesseningprivilege]

Power

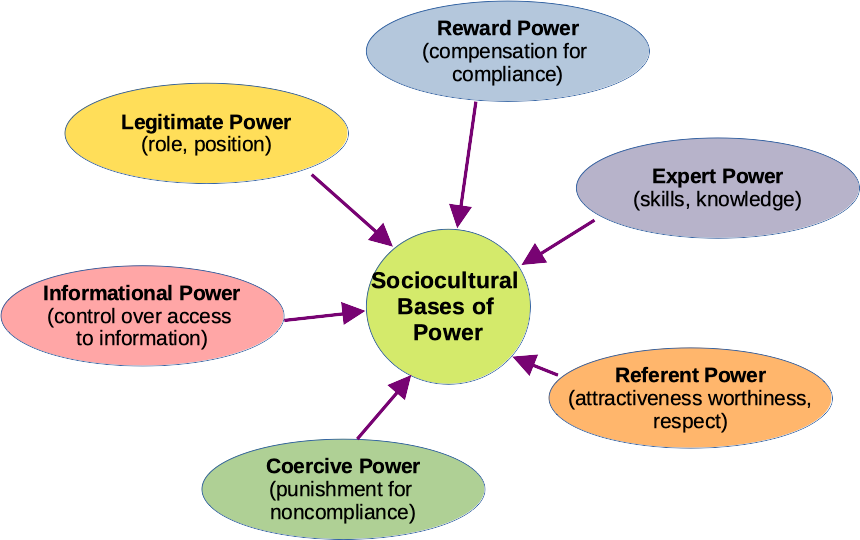

To understand your own positioning in relation to power and to begin talking with clients about power, it is helpful to understand the different types of power. Categorizations of power are most often tied to the work of French and Raven (1959) and Raven (1965). Consider the brief descriptions provided below.

Carefully consider each of these types of power in relation to your social location within the various contexts of your life and your relative social location with various clients. Power is not fixed; instead it is fluid and contextualized. Reflect on the ways in which you may need to mitigate power in certain relationships and, in other contexts, draw on your relative power to act with or on behalf of clients.

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc5/#understandingpower]

Sociocultural Construction of Meaning

Take a moment think about your favourite colour; then list as many words as you can that you associate with that colour. What assumptions might you make if a client described a feeling or experience using your colour?

Look for your favourite colour on this Colours in Culture chart to see what words may be associated with that colour in other cultures. Note: I am not assuming the chart reflects truth; the point is to honour diversity in meaning.

Finally look up some of the words you came up with to see if they appear on the chart. What colours are associated with those words in other cultures?

Reflect on the implications of this exercise for meaning-making with clients.

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc5/#colours]

Consider the implications of peeling off the labels we apply to each other for how you view yourself and how you might view your clients . Consider what it might mean to accept the idea that many of the things we hold as truths are simply a reflection of the sociocultural context in which we developed our sense of self and the world around us. Watch the YouTube video I am NOT black, you are NOT white.

© Prince Ea (2015, November 2)

Consider the following questions for reflection:

- What are the implication of recognizing that many of the labels we use are sociocultural constructions designed to make meaning of our experiences?

- What might happen if we began to peel some of these labels away? What might be lost? What might be gained?

- How does the concept of sociocultural construction of meaning influence how you might approach your work with clients?

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc5/#peelinglabels]

[Contributed by Vivian Lalande and Ann Laverty]

Listen to the following guided visualization through the audio link below.

For your convenience, the material is also available as a PDF file: Powerful Women. Now, respond to the following prompts:

- Describe the appearance of the powerful woman and how she interacted with others.

- Describe your own feelings about her and whether you would approach her.

- Identify any stereotypes of powerful women you may hold and the origins of these beliefs.

- Brainstorm a number of powerful women in society today, including women in politics, entertainment, sports, your community, your family, and school. What do these women have in common?

- Look at your list, and see how many of these women have identifiable nondominant identities (in addition to gender). What are the implications of this?

Based on your gender, reflect on how these messages about powerful women have made you feel in the past or in the present or how they may differ from the messages you have received about your own gender.

What practices can we utilize in families, schools, and extracurricular activities to promote increased androgyny and less overt and covert gendering of children? What are the implications for our roles as counsellors?

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc5/#powerfulwomen]

Social Location

Relative privilege–marginalization (Self-study or partner activity)

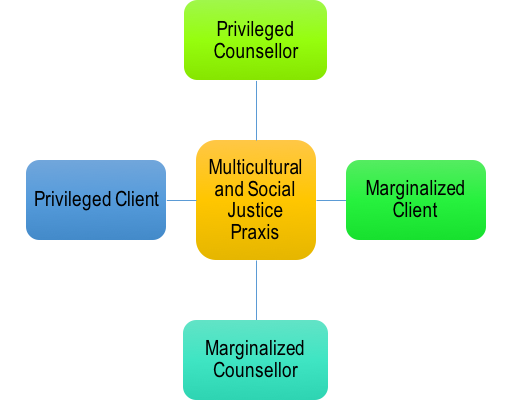

The social location of an individual or group of people refer to their status or position within the social, economic, or

political structures and systems within society. Social location is most often related to various dimensions of cultural identities and relationalities. Consider the diagram below, adapted from the Multicultural and Social Justice Counseling Competencies endorsed by the American Counseling Association (Ratts et al., 2015, p. 4). One’s relative position of privilege or marginalization is an essential starting place for applying the competencies for CRSJ counselling. For example, the process of addressing power imbalances will differ depending on the how the client and counsellor perceive themselves, in-the-moment, in relation to the diagram below.

| An audio file is provided to the right for individuals who prefer an oral description of the diagram. |

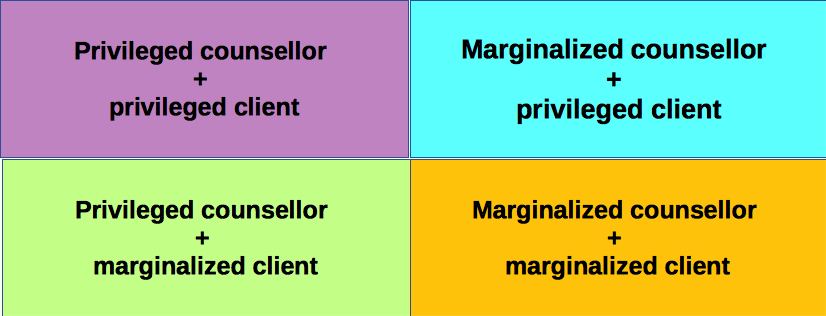

Now, imagine a client that fits each quadrant of the table when positioned relative to your own cultural identities and social locations. Note that this model challenges the biased assumption that counsellors are always in positions of relative privilege and requires a more nuanced approach to applying CRSJ counselling competencies, although the inherent power of counsellor role must always be taken into account.

| An audio file is provided to the right for individuals who prefer an oral description of the diagram. |

Reflect first on your sense of confidence and comfort heading into a counselling session with each client. What are the implications of your gut reactions for navigating power and privilege in your relationship with clients? What possibilities exist for unintentional oppression to emerge through the counselling process in each scenario? Find the cluster of the Multicultural and Social Justice Counseling Competencies (Ratts et al., 2015) that support socially just practice for the two combinations with which you feel least competent. Identify two competencies in each of these areas to focus on in your continued personal and professional development.

If you are completing this activity with a partner, you may consider role-playing a client–counsellor interaction for the scenario you each found most challenging.

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc5/#relativeprivilege]

References

Arthur, N., & Collins. S. (2016). Culture-infused counselling supervision: Applying concepts in clinical supervision practices. In B. Shepard, B. Robinson, & L. Martin (Eds.), Clinical supervision of the Canadian counselling and psychotherapy profession (pp. 353-378). Canadian Counselling and Psychotherapy Association.

Arthur, N., & Collins, S. (2017). Culture-infused counsellor supervision. In N. Pelling, A. Moir-Bussy, & P. Armstrong (Eds.), The practice of clinical supervision (2nd ed., pp. 267-295). Australian Academic Press.

Galbin, A. (2014). An introduction to social constructionism. Social Research Reports, 26, 82-92. https://www.researchreports.ro/images/researchreports/social/srr_2014_vol026_004.pdf

Gergen, K. J. (2015). An Invitation to Social Construction (3rd ed.). Sage.

Ratts, M. J., Singh, A. A., Nassar-McMillan, S., Butler, S. K., & McCullough, J. R. (2015). Multicultural and social justice competencies. Multicultural Counseling and Development, Division of American Counselling Association website: http://www.counseling.org/docs/default-source/competencies/multicultural-and-social-justice-counseling-competencies.pdf?sfvrsn=14

Ratts, M. J., Singh, A. A., Nassar-McMillan, S., Butler, S. K., & McCullough, J. R. (2016). Multicultural and social justice counseling competencies: Guidelines for the counseling profession. Journal of Multicultural Counseling & Development, 44(1), 28-48. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmcd.12035