Domain III: Embrace Cultural Responsivity and Social Justice as a Foundation for Professional Identity

CC8 Cultural Responsivity and Social Change

Embrace cultural responsivity and assume an anti-oppressive stance that fosters social change.

Recommended Reading

Collins, S. (2018). Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: A foundation for professional identity. In S. Collins (Ed.), Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: Re-shaping professional identity in counselling psychology (pp. 343–376). Counselling Concepts. https://counsellingconcepts.ca/

The eighth competency in the CRSJ counselling model (Collins, 2018), shifts the focus away from examining the cultural identities and social locations of counsellor and client to the nature of the professions of counselling and psychology. The activities in the guide to this point have engaged you in a process of consciousness raising about culture and social justice. Through the competencies in this domain, I invite you to consider how this awareness translates into action. First, I position cultural humility as an essential foundation for cultural competency. Cultural humility requires students, counsellors, instructors, and supervisors to position themselves as learners and to assume an other-orientated relational stance (First Nations Health Authority, n.d., Definitions section, para. 2; Hook et al., 2013). This positioning is supported through three essential skills: reflective practice, critical thinking, and cognitive complexity. Learners are encouraged to apply these skills to deconstruct dominant discourses within the profession and to actively position themselves relative to the call for social justice. I argue that, in a world in which basic human rights regularly come under fire, figuratively and literally, to assume anything other than active anti-oppressive and justice-doing stance supports the status quo (Collins & Arthur, 2018). Raising questions about professional identity, at the individual and collective levels, often begins with the ethical guidelines for the professions. Professional codes of ethics most often reflect core values grounded in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Gauthier & Pettifor, 2012); however, this social justice agenda is only rarely articulated explicitly in these codes (Audet, 2016; Counselors for Social Justice, 2011).

The activities in this chapter are designed to support competency development related to the key concepts listed below. Click on the concepts in the table and you will be taken to the related activities, exercises, learning resources, or discussion prompts.

Anti-Oppressive Stance

Lightly review (i.e., skim to get a sense of the contents) the following guidelines for affirmative therapy with gender nonconforming or sexual minorities, attending to only the overview of each guideline, not the detailed explanations.

- Guidelines for psychotherapy with lesbian, gay, and bisexual clients (American Psychological Association [APA], 2021)

- Competencies for counseling with lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer, questioning, intersex, and ally individuals (American Counseling Association, [ACA], 2012)

- Guidelines for Psychological Practice With Transgender and Gender Nonconforming People (APA, 2015)

- Competencies for counseling with transgender clients (ACA, 2009]

The guidelines published by professional organizations like the APA and ACA are well grounded in the scientific and professional literature and continue to evolve over time. They are an excellent source of current information. As professional counsellors, we are responsible for knowing and enacting these bodies of professional knowledge. Select two of the principles (from any of these documents) that you think might be the most challenging for you to implement in your work with LGBTTQI clients. Read the more detailed explanation of those principles and do a bit more research on them, drawing on the resources below.

- Consider the Policy and Position Statements on the Canadian Psychological Association website.

- Review the list of Reports by Topic as well as other materials under Psychology Topics on the APA website.

- Look through the topics covered through the Knowledge Centre of the ACA (click on the Knowledge Center link on the main menu).

What did you learn from your research that either increased or decreased your personal comfort with, and commitment to, adopting the LGBTTQI affirmative stance of the professions of counselling and psychology? How will you address any lingering personal cultural biases that are a barrier to affirmative practice? How might you generalize your learning to your interactions with members of other cultural groups?

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc8/#adoptingantioppressive]

Codes, Principles, Standards, and Guidelines

Codes, principles, standards, and guidelines: Necessary but not sufficient (Class discussion)

[Adapted from Pettifor (2010)]

Jean Pettifor was a highly influential person in professional ethics in Canada. In reflecting on her involvement in ethics, she shared some of her personal history in Pettifor (2010).

Looking back, I was probably born into ethical thinking, even if it was not so named. My parents were concerned about poverty, poor distribution of goods, exploitation of western farmers, racism, threat of annihilation through wars, inadequate medical and educational services, unequal opportunities for women, the criminality of birth control – in other words, social justice for all. I became a psychologist still believing that I had, and others should have, a commitment to help people build a better life. I never adopted the position that my employment with the provincial government was just a job that required conformity to directions from management if such direction was harmful to clients. My belief was that the vulnerable should always be protected. . . . My mission now is to promote value-based ethical decision-making that truly respects and cares for all persons. (p. 167)

Later in this chapter, she argued that

Respect, caring, and integrity are the moral foundations for professional ethics. . . . Moral principles of respect and caring are aspirational in striving for optimal levels of care, address relationships among persons and peoples, and supersede prescriptive behavioural standards that define correct conduct. (p. 168)

Pettifor (2010, p. 171) introduced two approaches to ethics that influence how, and to what degree, ethical codes, principles, standards, and guidelines in counselling and psychology may be applied to particular ethical dilemmas.

- The deontological position of Emmanuel Kant (1724-1804) . . . ethical decisions are based on moral imperatives of intrinsic rightness – that each person must be treated as an end and never as means to an end.

- The utilitarian or consequentialist position of Mill (1806-1873) and Bentham (1748-1832) . . . the ethical decision is the one that brings the greatest good, happiness, or outcome for the greatest number, or the least harm, and that sometimes the end may justify the means.

A third approach, virtue ethics, diverges from principle-driven approaches by asking “what a virutuous person would do under the circumstances” (Schultz & Martin, 2015). Watch the short video below, which introduces virtue ethics and contrasts this position with deontology and consequentialism.

© CrashCourse (2018, January 7)

Then consider the following scenario adapted from Pettifor (2010, p. 169).

A local community organization hires a cisgender, male, Asian-trained counsellor to provide mental health services in the Asian immigrant community in a large Canadian city. The counsellor is a refugee himself, having barely escaped the political violence in his home country. He is trying to obtain permission for his family to join him in Canada. He is deeply grateful for his job and for having a means of livelihood.

After he has been on the job for six weeks his supervisor reprimands him for visiting families in their homes and attending their community social functions. The supervisor says that he is in a conflict of interest because he is not maintaining professional boundaries. Moreover, the supervisor asserts that he can see more clients in a day if they come to the office for appointments.

The counsellor is devastated. He has cultural respect for persons in authority, he cannot afford to lose his employment, and therefore he feels unable to defend his position. He also lives in the Asian community where he practices. At the same time, he knows that, culturally, many of his Asian clients do not view mental health and illness in the North American way, and if he is aloof and not accepted, he cannot help them.

The counsellor shares this scenario with you as colleagues in the context of a peer consultation group. Identify (a) the ethical dilemmas it may present, (b) the relevant codes, principles, standards, and guidelines you might consider; and (c) the impact of applying each of the three ethical lenses (deontological, utilitarian or consequentialist, and virtue ethics). Consider the possibility of a both-and approach by reflecting critically on the risks and benefits an aspiration versus a prescriptive position. Brainstorm possibilities for how the counsellor in this scenario might address the ethical dilemmas with his supervisor?

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc8/#necessary_sufficient]

Cognitive Complexity

Think about your thinking by comparing and contrasting the characteristics of cognitive complexity versus cognitive rigidity below. Honestly appraise your own cognitive tendencies, and consider how these might be assets or barriers to your implementation of CRSJ counselling competencies. It is very important to not fall into either/or thinking; this applies in your thinking about thinking as well, because you will likely recognize both thinking patterns in yourself. Identify the contexts, relationships, issues, or other variables that might incline you towards one or the other. What meaning do you make of these observations? What might the implications be for culturally responsive and socially just counselling practice of the cognitive style toward which you incline?

| Cognitive Complexity | Cognitive Rigidity |

|

|

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc8/#complexityrigidity]

Critical Thinking

First, search the Internet to create your own definition of critical thinking. Be sure to apply a critical lens to the sources you use to develop your understanding of this important concept.

Second, choose a nondominant population or a social justice issue about which (a) you personally hold or have held preconceptions that might not stand up to the test of critical thinking, or (b) you have encountered assumptions or biases in your personal interactions with others or through media sources. Articulate in 1–2 sentences the cultural preconception, assumption, or bias. Try to word your statement so that it does not immediately invite rejection, aiming for a more subtle, arguable position. Here are a couple of examples:

- Increasing the number of refugees admitted to our country reduces the available employment opportunities for citizens.

- Affirmative action hiring leads to preferential selection procedures that favour unqualified over qualified candidates, and therefore, disadvantages members of dominant populations.

Be brave yet humble and open. Put forth an argument with which you are struggling. If you have trouble coming up with an example, apply one or more of the principles of cognitive rigidity from the Cognitive complexity versus cognitive rigidity learning activity.

Third, apply one of the principles for how to practice critical thinking below as a first step in beginning to dismantle your own argument.

- Take up an unfamiliar or uncomfortable point of view to apply to the argument.

- Examine what information has been left out or misrepresented.

- Analyze the argument for signs of cognitive rigidity (e.g., overgeneralization, either/or thinking, linear causality).

- Identify and critique the underlying assumptions, and position these within broader ways of knowing or worldviews.

- Examine the evidence by researching and applying facts, observations, and counter-arguments.

- Research the common source(s) of the argument, and analyze related agendas or motivations; consider why people are putting forth this argument.

- Position the argument within different contexts or lenses (e.g., social, economic, political, moral, ethical, professional).

- Create a real life scenario in which to analyze the argument, moving from the abstract and decontextualized to the specific and contextualized.

- Imagine a context in which you might take up this argument, and critically analyze the factors that could contribute to its appeal.

- Break the argument down into the connections between ideas (i.e., if . . . then . . .) to challenge assumptions of linear causality.

- Engage in a cost-benefit analysis of the argument, attending to its impact on various persons or peoples.

- Look for signs of emotional reasoning. It is important to attend to other ways of knowing; however, it can also be valuable to examine critically our gut reactions.

Fourth, share with your peers (a) your argument (i.e., cultural preconception, assumption, or bias) and (b) one example of how you might begin to dismantle this argument drawing on the critical thinking practices above.

- In an online environment, your instructor will set up a questionnaire, wiki, or another interactive tool into which you can enter your cultural preconception, assumption, or bias. It is best if each person makes a contribution before viewing those of others.

- In a face-to-face environment, your instructor will collect your contribution and collate all responses to make them available to the whole group.

Fifth, engage in a group discussion of each of the arguments (i.e., cultural preconceptions, assumptions, or biases). Please choose one of the critical thinking practices below to apply to one of the arguments posted by your peers. Remember, the purpose of critical thinking is not to be judgmental; rather, it is to look at an idea from multiple angles to assess its validity.

Repeat this process with two additional practices and two other arguments to support an in-depth analysis of each peer’s contribution. Please choose arguments that have not yet been addressed, so that each participant receives feedback on the argument they shared.

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc8/#thinking]

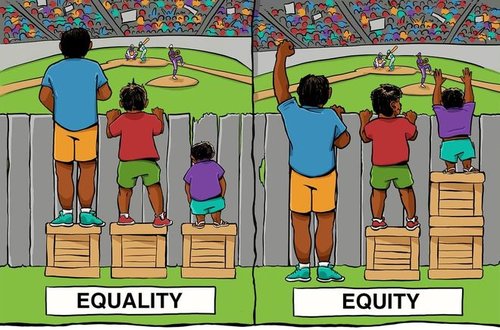

Equity Versus Equality

Consider the following image designed to differentiate between the concepts of equity and equality.

| An audio file is provided to the right for individuals who prefer an oral description of the diagram. |

Pair up with a colleague or peer to discuss your interpretations of the image and the meaning it has in terms of fostering social justice in society. Then, create a client scenario that would demonstrate a shift from equality to equity. Consider both how that person might be treated within the counselling context and how you, as a counsellor, might help facilitate change in the direction of greater equity in the broader contexts of that client’s lived experiences. Check out your scenario with your colleague or peer to see how well the scenario illustrates these principles.

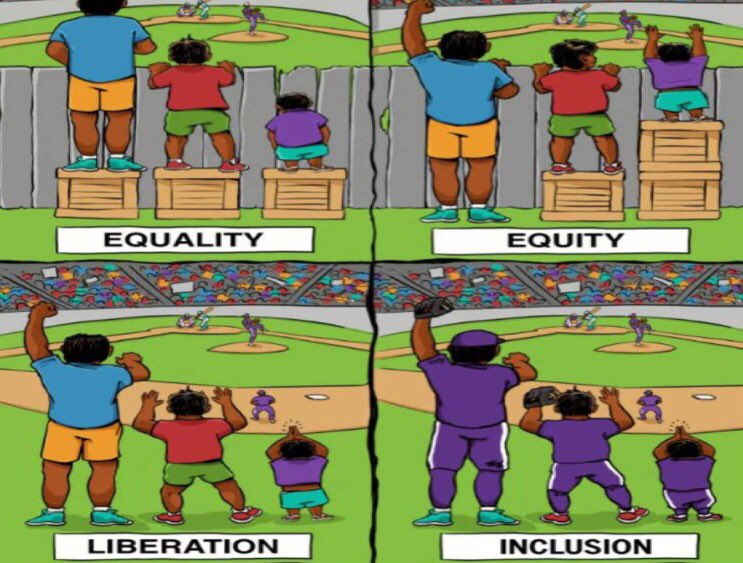

Now consider the image below that extends these concepts further. What are the implications of liberation for culturally responsivity and social justice in counselling practice? Extend your scenario above to include this lens.

| An audio file is provided to the right for individuals who prefer an oral description of the diagram. |

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc8/#shiftingtoequity]

Ethical Decision-Making

Personal factors in ethical decision-making (Self-study)

[Contributed by Simon Nuttgens]

Most ethical decision-making models include a step that involves careful examination of personal factors that influence how we view, understand, and respond to difficult ethical choices. The importance of this step follows from research indicating that even when the ethically correct course of action is clear to us, we often fail to respond accordingly due to personal factors.

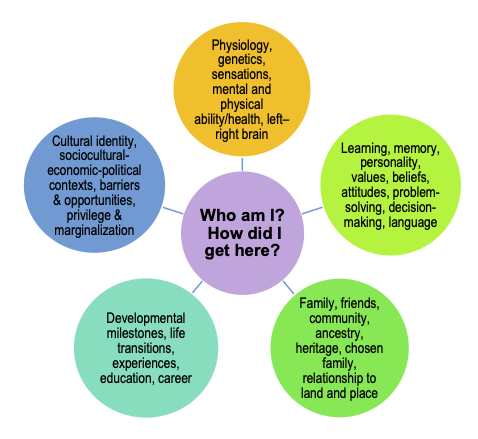

These personal factors are rooted in many aspects of our cultural identities. Review the Exploring the factors influencing personal cultural identities figure as a backdrop for this learning activity. Then complete the Personal factors inventory (MS Word version) to invite reflection on influential personal experiences, past and present, how they link to your core values, and how they influence your ethical reasoning. Ethical decision-making is inescapably coloured by our own personhood. To deny or overlook this axiom is to risk making decisions that are unduly influenced by personal biases, predilections, motivations, and emotional states.

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc8/#personalfactors]

Ethical Practice

[Contributed by Simon Nuttgens]

Attempts to untangle the moral values that underpin professional ethics from divergent moral values from other cultures or regions, unavoidably lead us to consider metaethics, defined by the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy as “the attempt to understand the metaphysical, epistemological, semantic, and psychological, presuppositions and commitments of moral thought, talk, and practice” (Sayre-McCord, 2014). In simpler terms, the purpose of metaethics is to pursue a philosophical understanding of ethics.

© CrashCourse (2016, October 25)

A basic understanding of metaethics will help bring clarity to questions such as:

- Are Western ethical principles valid across diverse cultures?

- Are some cultures more morally developed than others?

- Are moral beliefs and values universally valid?

- How might the moral beliefs and values of the counsellor, the client(s), and the profession interplay in ethical decision-making?

- Which of the moral principles (metaethics frameworks) best reflects your beliefs and values? What are the implications of this position for culturally responsive and socially just counselling practice?

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc8/#metaethics]

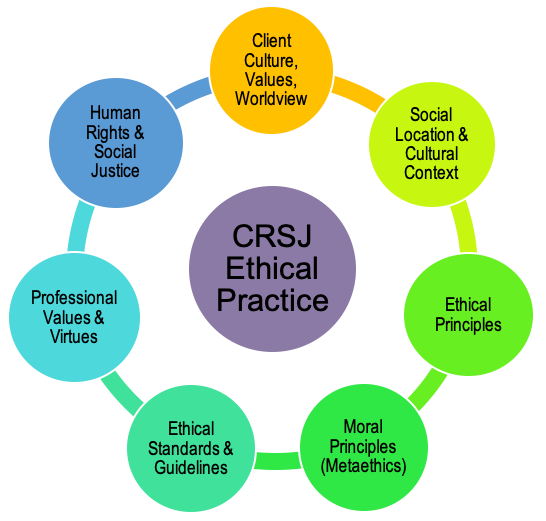

Ethics and CRSJ counselling: Assuming a both-and position

[Created in collaboration with Simon Nuttgens]

Fisher (2014) argued against taking an either-or position that privileges ethics over cultural responsivity, emphasizing that practitioners are not expected to be “moral technocrats simply working their way through a maze of ethical rules, but to be active moral agents committed to the good and just practice and science of psychology (Fisher, 2013)” (p. 36). The factors influencing CRSJ ethical practice below are drawn from Fisher (2014) and Collins (2018).

Work with a peer to apply a both-and perspective to the ethical dilemma below, paying careful attention to factors or issues on which you diverge in perspective and related to which either of you experience cognitive dissonance or emotional tension. Come up with as many possibilities as you can for how you might proceed; be specific about which of the factors influencing CRSJ ethical practice you draw on for each possibility.

You work in a small rural community in Quebec. Recently, some farmland near the town where you live was purchased by a young couple. They are recent immigrants, with small children, and each has siblings with children living with them on the land. The wife’s sister is homeschooling all of the children, who range in age from 5 to 15. The family does not speak French, but they do speak English. You are the only English-speaking counsellor in the area. They are also part a sister church community from their central American homeland, and they have been supported by your church community to make this transition. You were part of a small group of church members who helped with their immigration process, although you had a behind-the-scenes role.

Two of the children, aged 12 and 15, are referred separately to you for counselling. You are told that they were both exposed to traumatic events as a result of political unrest in their homeland, and they are each exhibiting behavioural changes. You rent office space for your counselling practice from the local school, where your wife is a teacher. You have seen the children in back-to-back sessions three times. Your wife, who is not part of the church community, noticed one of the adults from the farm dropping the children off prior to their sessions. She tells you she felt uneasy about the interactions between the adult and children, but cannot identify why with any specificity.

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc8/#bothand]

Human Rights

A basic premise of the CRSJ counselling model is that counsellors, psychologists, and other helping professionals have an ethical and professional responsibility to take an active stance in advancing equity, social justice, and human rights within the professions as well as within society as whole. However, it is important that we do not simply take up terms like social justice and human rights without being able to articulate clear and sound arguments for their integration into codes of ethics, counsellor education, and professional practice. We must also be prepared to respond in a reasoned way to the counter-arguments that are increasingly emergent nationally and internationally.

For this class discussion, please choose one of the following conversational roles to ensure that the metacognitive skills of critical thinking, cognitive complexity, and reflective practice are actively employed in the dialogue.

| Conversational Roles |

| The Critical Thinker: Your task is to encourage deeper thought, to point out gaps in the evolving argument (not in individual student posts), and to draw attention to diverse perspectives. |

| The Cognitive Complexifyer: Your task is to encourage both/and thinking, to bring in different lenses or frames of reference, and to point out paradoxes or tensions that are not easily resolved. |

| The Reflective Practitioner: Your task is to ensure participants reflect critically on their own values, assumptions, and beliefs, and to foster participant self-awareness of cultural lenses and worldviews. |

Your instructor may also choose to set this discussion up as a debate, assigning half the group to argue for, and half to argue against, the position below.

Next, carefully consider the argument (below) drawn from Salzman (2019), who takes the position that social justice stands in opposition to free speech. Engage in a dialogue with your peers to analyze critically this position, carefully considering both arguments and counter-arguments.

Most professors and students in the social sciences, humanities, education, social work, and law, and most university officials at Canadian and American universities today have adopted a political ideology labelled “social justice,” which requires redress for categories of people deemed “oppressed” for reasons of race, gender, sexual preference, ethnicity, and/or religion. . . . “Social justice” ideology is upheld in a variety of ways detrimental to free speech and open discussion. . . . This enforced monopoly of ideas goes counter to the traditional view of universities as a “marketplace of ideas” where students had the opportunity to open their minds to a wide range of ideas, and different theories and arguments were tested against one another. . . . The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms itself has a “social justice” provision that waives the rights of the majority in favor of disadvantaged minorities. While provision 15-1 states that “Every individual is equal before and under the law and has the right to the equal protection and equal benefit of the law without discrimination and, in particular, without discrimination based on race, national or ethnic origin, color, religion, sex, age or mental or physical disability,” provision 15-2 states that 15-1 does not preclude laws or activities for the “amelioration of conditions of disadvantaged individuals or groups . . . because of race, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, sex, age or mental or physical disability.” This 15-2 provision, like every “social justice” measure, ignores the fact that giving special benefits to one category of people inevitably blocks others from those benefits, and thus undermines treating individuals fairly and justly according to their individual human rights and their merits. (para. 1, 3, 4, 23, 24)

Drawing on what you learn from this conversation, reflect on how you might best articulate your own position on human rights and social justice in a way that is professional, ethical, and supportable.

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc8/#sjargument]

Inclusivity/Diversity

One of the risks that counsellors face when their primary exposure to diverse cultural experiences is through their clients (or that counselling students might encounter when they immerse themselves in the reality of social injustices and inequalities) is assuming a problem-focused perspective on persons or peoples from nondominant populations! This is a form of othering.

Listen to some of the stories of resilience, strength, creativity, courage, and cultural celebration (in the videos below). Remind yourself that culture and diversity are not the problem. The problem is in the stratification of society and the dominant discourses of marginalization and exclusivity. It is important to challenge continually the ways in which we construct meaning around difference, which in some cases leads members of dominant society, including healthcare practitioners, to continue to forefront difference, even in their attempts at inclusivity and social justice. What if it is actually difference, rather than sameness, that defines what is normal, healthy, or simply human. Some of these videos are a bit longer (15–20 minutes), so watch only what you have time for, but choose at least one to encourage you to celebrate diversity!

© TEDxSydney (2014, April)

© TEDWomen (2016, October)

© TEDWomen (2015, May)

© TEDx (2014, July 16)

One of the greatest strengths of Canada, and many other nations, is its cultural diversity. Let’s remind ourselves that we are exploring these challenging issues, within our society and within ourselves, to increase our commitment to the values of inclusivity and diversity.

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc8/#letscelebrate]

Professional identity

Who am I? Integrating the personal and the professional (Class discussion)

[Contributed by Sarah Stewart-Spencer in collaboration with Sandra Collins]

Consider the influences on your life story and professional identity development, drawing on the diagram below.

Reflect on the people, contexts, events, and moments that have influenced your personal and professional development. Consider how your experiences have led you to become a counsellor, psychologist, or other helping professional. Provide an overview of your personal development journey, and describe how you believe you have been shaped along the way to become a healthcare practitioner. Include your qualities, skills, attitudes, personal beliefs, and strengths that will influence you in your continued professional identity development.

Feel free to be creative by sharing your journey in the form of a collage, mind map, wordle, diagram, or another arts-based way of expressing your self-reflections.

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc8/#whoamI]

Worldview assumptions and metatheoretical approaches to change (Class discussion)

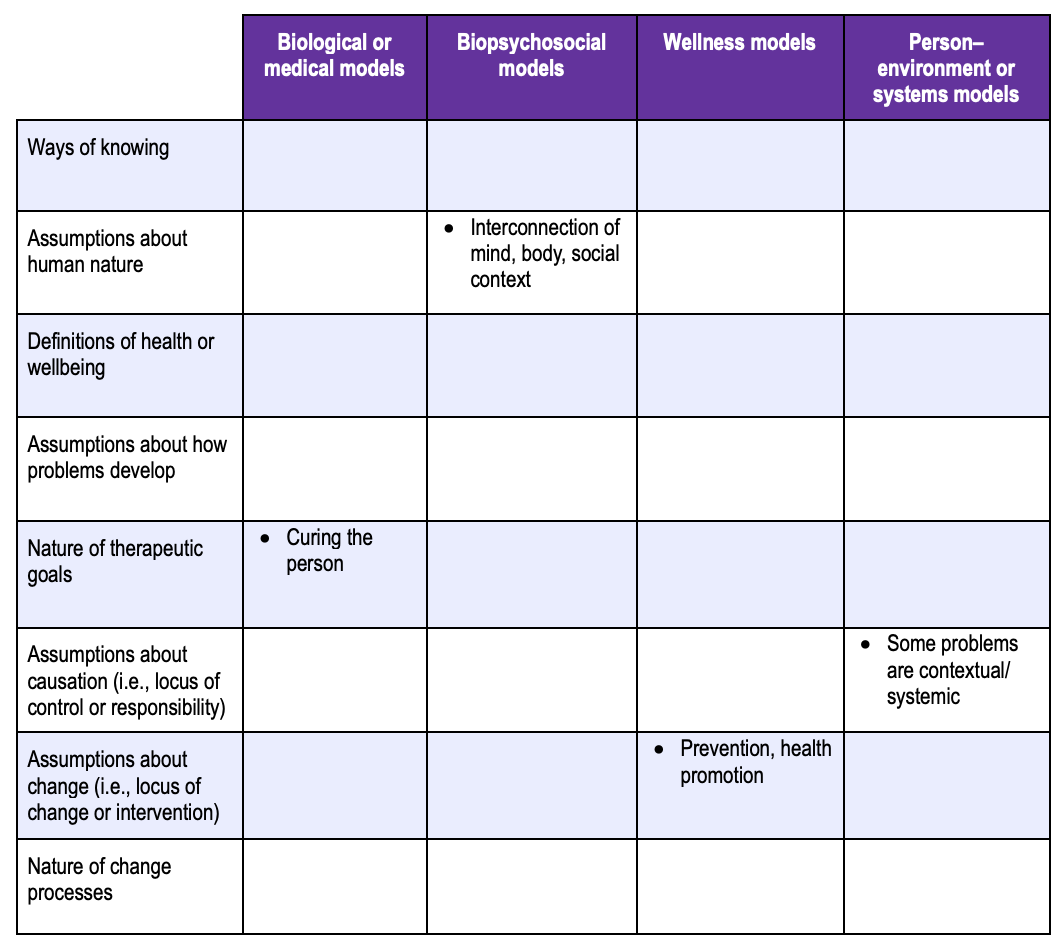

The professions of counselling, psychology, and psychotherapy in Canada continue to refine their professional identities in relation to each other and in response to emerging research and theory related counselling efficacy across clients, cultures, and contexts. The purpose of this learning activity is to examine the worldviews that ground various metatheoretical helping models that influence professional identity and approach to practice.

In partners or in small groups, use reliable Internet sources to complete the following chart (PDF version) with the goal of bringing to the foreground the underlying assumptions of various metatheoretical models that influence professional identity. These models may not be mutually exclusive. Consider using a wiki to collaborate in online contexts, or use the MS Word version.

Engage in a discussion as a class or large group, drawing on the following prompts and digging deeply into the worldview positionings (i.e., beliefs, values, assumptions) that undergird various models.

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of adopting each metatheoretical approach (for clients, for practitioners, for society)?

- What might be gained or lost as a profession by focusing on one or more of these approaches?

- What are the implications of what you have learned through this activity for your individual and collective understanding of the professional identity.

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc8/#metatheoretical]

Reflective Practice

Inside Voice (Class discussion)

[Contributed by Simon Nuttgens]

When professional values, established through ethical codes, laws, and so forth, conflict with the cultural values of your client, it is important to adopt a reflexive posture, attending closely to personal thoughts and emotions as they arise. Doing so allows us to (a) identify and question assumptions and biases, (b) regulate our emotional responses so that they do not direct our outward actions, and (c) embrace an open and curious way of being with our clients.

In this fictional account, you are in the midst of your second session with a family of four, who self-identify as first generation immigrants. The family consists of husband (Otrun), wife, (Astur) and two children, a boy aged 13 (Chak), and a girl aged 10 (Shonnal). They were asked to see you by Chak’s school, because of reports of aggressive and defiant behaviour by Chak. We pick up midway through the second session, with Otrun sharing his thoughts on the concerns noted by school personnel.

As you read the Client-Counsellor Dialogue (MS Word version), take note of the thoughts and feelings that arise for you, but that you would not likely voice if you in a counselling session (hence, “inside voice”). Try also to image the inside voices of the clients. Once you have taken notes on all of the counsellor-client exchanges, read through your responses to identify key themes and insights.

Post your reactions (online) or share them with your peers (in-class) to the Inside Voice exercise, drawing from the notes you took. Bring your personal and professional selves into the discussion by being honest about the thoughts and feelings that arose as you worked through the vignette. Discuss strategies for honouring ethical values, cultural values, and personal values in this and similar scenarios.

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc8/#innervoice]

Social Justice

[Note to instructors: You may want to find a way for students to share initial responses anonymously to facilitate honest dialogue. Please also remind learners of their responsibility to balance engage honestly yet respectfully in all conversations.]

Share with your peers a Yes, and . . . statement about the human rights, social justice, and positioning in society of persons or communities with whom you continue to struggle to find common ground or for whom you find it difficult to embrace fully their rights to self-determination. For example:

- Yes, I think that transpersons should be protected from discrimination . . . And we also have to think about women and girls who may not feel safe sharing a washroom with someone who is genetically a “man.”

- Yes, we all benefit from Canada’s relatively open immigration policy . . . And I sometimes feel like I am the one that doesn’t belong in my community any more.

- Yes, I want people from all religions to feel welcome and comfortable in Canada . . . And Canada has traditionally been a Christian country, and we are losing that part of our cultural identity.

Be as honest as you can about your lingering challenges (biases?), and be open and inviting of feedback from your peers. Feel free to be creative in how you express your Yes, and . . . expression. However, you are expected to be respectful of your peers and to recognize that your classmates represent diverse cultural identities, social locations, and worldviews.

If you can’t come up with an honest Yes, and . . . of your own, please discuss this with your instructor. They may permit you to identify one that you have heard from others in your personal or professional life that you can use.

Next, provide feedback to your peers by drawing on the current literature, such as scientific evidence about diversity in cultural identities, emergent consensus on professional values, counsellor identity development, and so on (i.e., not your personal opinions!). The goal is to develop an informed counter-argument for the Yes, and . . . statement.

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc8/#yesand]

Unintentional Oppression

Strategies for mitigating unintentional biases (Partner or small group activity)

Unintentional oppression can occur when counsellors fail to bring into conscious awareness cultural assumptions or biases they hold. Review the examples below to contrast intentionally versus unintentional biases in counselling theories, practices, and relationships. I have used the principle commonly applied to define harassment to discern between intentional and unintentional behaviour, recognizing this not always as clear: i.e., oppression can be considered intentional if the practitioner knew, or ought reasonably to have known, the behaviour to be offensive, discriminator, or culturally insensitive. I invite you to critique the choices presented based on this criteria.

| Intentional Oppression | Unintentional Oppression |

| A counsellor chooses to continue to use the pronoun he, even though the client introduced the preferred pronoun, they, on the intake form. | A counsellor purchases chairs with arms for their office without considering the comfort level of clients with larger bodies. |

| A counsellor requires all clients to commit to participate in group work, which is only available in the evenings. | A counsellor provides hand-written notes to their clients in cursive script, which some clients are unable to read. |

| A counsellor employs the same therapeutic intervention with all clients who present with anxiety, without attention to unique client factors. | A counsellor decides that the best way to avoid superimposing their own religious beliefs is to avoid addressing spirituality altogether with their clients. |

| A counsellor refuses to allow extended family members to attend counselling sessions, even though the client has requested their participation. | A counsellor presumes that their client has made unhealthy or ineffective choices that have resulted in their financial distress. |

In many cases, unintentional oppression emerges as a result of unexamined stereotypes. Which stereotypes might leave you vulnerable to unconscious bias?

Consider the following strategies for mitigating bias, adapted from Canada Research Chairs (2018). How might these techniques help you address unintentional oppression in your relationships with your clients?

- Stereotype replacement: Think about a stereotype that you may be applying to this particular client, and replace it consciously with accurate information.

- Positive counterstereotype imaging: Picture someone from the same cultural group as the client, who behaves or thinks in way that is counterstereotypical to the assumptions you are inclined to make about members of this cultural group.

- Perspective taking: Assume the perspective of a client from within the stereotyped group.

- Individuation: Gather specific information about the client to prevent group stereotypes from leading to potentially inaccurate assumptions.

[Permanent link: https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc8/#mitigatingbias]

References

Audet, C. (2016). Social justice and advocacy in a Canadian context. In N. Gazzola, M. Buchanan, O. Sutherland, & S. Nuttgens (Eds.), Handbook of counselling and psychotherapy in Canada (pp. 95–122). Canadian Counselling and Psychotherapy Association.

Canada Research Chairs. (2018). Bias in peer review. http://www.chairs-chaires.gc.ca/program-programme/equity-equite/bias/module-eng.aspx?

Collins, S. (2018). Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: A foundation for professional identity. In S. Collins (Ed.), Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: Re-shaping professional identity in counselling psychology (pp. 343–403). Counselling Concepts. https://counsellingconcepts.ca/

Collins, S. (2018). Expanded CRSJ) counselling model. In S. Collins (Ed.), Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: Re-shaping professional identity in counselling psychology (pp. 21–49). Counselling Concepts. https://counsellingconcepts.ca/

Collins, S., & Arthur, N. (2018). Challenging conversations: Deepening personal and professional commitment to culture-infused and socially just counselling processes. In D. Paré & C. Audet (Eds.), Social justice and counseling (pp. 29–41). Routledge.

Counselors for Social Justice. (2011). The Counselors for Social Justice code of ethics. Journal for Social Action in Counseling and Psychology, 3(2), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.33043/jsacp.3.2.1-21

First Nations Health Authority. (n.d.). Definitions. http://www.fnha.ca/Documents/FNHA-Cultural-Safety-and-Humility-Definitions.pdf

Fisher, C. B. (2014). Multicultural ethics in professional psychology practice, consulting, and training. In F. T. L. Leong, L. Comas-Díaz, G. C. Nagayama Hall, V. C. McLoyd, & J. E. Trimble (Eds.), APA handbooks in psychology. APA handbook of multicultural psychology, Vol. 2. Applications and training (pp. 35–57). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/14187-003

Gauthier, J., & Pettifor, J. L. (2012). The tale of two universal declarations: Ethics and human rights. In A. Ferrero, Y. Korkut, M. M. Leach, G. Lindsay, & M. J. Stevens (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of international psychological ethics (pp. 113–133). https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199739165.013.0009

Hook, J. N., Davis, D. E., Owen, J., Worthington, E. J., & Utsey, S. O. (2013). Cultural humility: Measuring openness to culturally diverse clients. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60(3), 353–376. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032595

Pettifor, J. (2010). Ethics, diversity, and respect in multicultural counselling. In N. Arthur & S. Collins (Eds.), Culture-infused counselling (2nd ed., pp. 167–189). Counselling Concepts.

Salzman, P. C. (2019, March 23). The growing threat of repressive social justice. Frontier Centre for Public Policy. https://fcpp.org/2019/03/23/the-growing-threat-of-repressive-social-justice/

Sayre-McCord, G. (2014, Summer). Metaethics. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/metaethics/#Aca

Schulz, W. B., & Martin, L. (2015). The development of counselling ethics in Canada. In L. Martin, B. Shepard, & R. Lehr (Eds.), Canadian counselling and psychotherapy experience: Ethics-based issues and cases (pp. 1–23). Ottawa, ON: Canadian Counselling and Psychotherapy Association.