14

James Stump

As the Project Leader for a research grant on human identity, I interact and work with many people who experience a barrier in reconciling evolutionary science with their theological tradition. The particular fear voiced most often is that evolutionary science will undermine the concept of the human person they have inherited from their faith. In response, as the Project Leader for BioLogos (a nonprofit organization founded by Francis Collins) I attempt to illustrate in this chapter how science does not undermine theological concepts of the human person. In addition, I urge people to resist jumping to that verdict without analyzing and assessing recent work in various disciplines. As I do so, the question that pervades my research is: what does it mean to be human in light of evolutionary science and Christian theology? A wide range of different topics and questions could be included in this question. However, my own training has drawn me to the philosophical aspects of the question of language: whether it is uniquely human, and more particularly, how it contributes to our experience of the world. For the purposes of this chapter, I have applied my developing views and claims on language to the concept of wisdom and pointed toward some relevant avenues for further inquiry.

We live in a Different World because of Language

Ernst Cassirer was a mid-twentieth century philosopher, best known in academic circles for his massive study The Philosophy of Symbolic Forms. In a more popularly-oriented book published in 1944 he wrote:

No longer in a merely physical universe, man lives in a symbolic universe…No longer can man confront reality immediately; he cannot see it, as it were, face to face. Physical reality seems to recede in proportion as man’s symbolic activity advances. Instead of dealing with the things themselves man is in a sense constantly conversing with himself. He has so enveloped himself in linguistic forms, in artistic images, in mythical symbols or religious rites that he cannot see or know anything except by the interposition of this artificial medium.[1]

What if Cassirer had lived in the twenty-first century? The “physical reality” many of us encounter on a daily basis is splotches of ink on a page or, increasingly, patterns of pixels illuminated on a screen. These splotches and pixels transport us into a symbolic universe where we rarely notice the physical realities. And whether academics or not, we live in a world that is populated with things like nations and political parties, sitcoms and cricket matches, religion, and conferences. Where does wisdom fit into this world? I want to approach this question from the perspective of language in conversation with several recent books that acknowledge a constitutive role for language. By drawing on the work of Terrence Deacon, Charles Taylor, Mary Midgley, and Rowan Williams, I will develop the argument that our words do not merely name things that exist independently of us. Rather, the symbolic nature of language allows for an interplay between words and ways of being such that our human activities cannot be understood apart from the influence that language has on them. These activities constitute much of our waking lives, so there follows the claim that we live in a different world than that of species without language.

It is an open question whether we, humans, are the only species on earth to possess language. This question is beyond the purview of this chapter, but I will draw upon the work of the anthropologist Terrence Deacon to briefly elaborate.[2] Deacon claims there is a qualitative difference between the symbolic language we use and communicative signs that merely act as indices, such as the different calls vervet monkeys use for different kinds of predators they detect; bees that do a little dance to indicate to other bees where the nectar is; and even trees in a forest that communicate with chemical signals distributed through an underground network of fungi. All the trees, bees, and monkeys are doing is responding instinctively to a sign that is correlated with some bit of physical reality—they do not know what it “means.” More controversially, but still plausibly defensible in my mind, is the proposition that when apes are trained to use some sign language, they are similarly communicating, but not thinking symbolically. From the description of these situations, we might see these signs as referring to other things. But even the word “refer” carries with it other connotations that we can’t easily disregard in our assessment of the situation. This is Deacon’s point about symbols: they not only refer to some object in the “real” world, but they also refer to other symbols. They are situated within a complex system of symbols with a high level of interplay between them. There are no one-word languages. Too often our attempt to understand what language is doing is modeled on simple situations that can mostly be treated in isolation from the rest of our language like, for example, referring to this desk or that tree outside. The topic addressed in this volume, wisdom, is a much more interesting example of the power of symbolic language. It does not have a direct referent in the physical world as the word “tree” does, nor does it even have a fairly straightforward definition like other abstract nouns (e.g., “democracy”). The meaning of “wisdom” is caught up in its relationship with other words. But this is not just a circle of words that relate to each other; these words and concepts constitute something more. They frame the way we experience the world, opening us to subtleties and differences we would not see if we had no words for them.

In his very interesting recent book The Language Animal, Charles Taylor advocates for the constitutive view of language stemming from the philosopher Johann Herder, who argues that language makes possible a different kind of consciousness.[3] This begins with the insight that pre-linguistic beings can react to their surroundings, but language enables us to “grasp something as what it is” and opens up new aspects of an agent’s mental life.[4] As a person with language, I now can wonder if I have grasped a situation correctly. Is “anger” the right word for what I’m feeling, or does this emotion differ enough to be called something else, like “indignation” or “resentment?” As my language takes on a finer grain, my experience itself reflects that. According to Taylor, linguistic beings are ushered into the realm of values and morality: was my response of indignation an appropriate response to the situation? For Taylor, “prelinguistic animals treat something as desirable or repugnant by going after it or avoiding it. But only language beings can identify things as worthy of desire or aversion.”[5] Language opens up a new range of experiences, a more complex gamut of emotions, and even introduces values. These seem to set us apart in radical ways from non-linguistic beings. Taylor notes:

We can’t explain language by the function it plays within a pre- or extra linguistically conceived framework of human life, because language through constituting the semantic dimension transforms any such framework, giving us new feelings, new desires, new goals, new relationships, and introduces a dimension of strong value.[6]

Perhaps we can claim, on this view, that wisdom is one of those things that has opened up to us because of language. Wisdom was not something existing independently of us in the sense that we merely bumped into it at some point in our species’ history and gave it a name, like discovering the planet Neptune. But neither is it true to say that we have “made it up,” so to speak, as we have made up, say, academic conferences. Wisdom is part of the symbolic world, but it is not merely a construct. This statement requires further nuance, so here is my next claim:

The Symbolic World is not Reducible to Physical Realities

Think of words like indignation, academic conferences, and British pounds. It seems correct to say that these words merely name constructs or social realities. For a clearer example, consider unicorns. We could all give some conceptual analysis of a unicorn and agree that it is horse-ish, one-horned, and frequently appears around rainbows. But that broad agreement does not somehow confer reality onto unicorns. From this example, it is safe to say that we have words for things that do not really exist apart from our words. They are merely conventions. Moving a little further down the spectrum toward the less clear examples: what about a species? To what does that word refer? Does it have reality above and beyond the individuals that comprise it? What exactly went out of existence when the last dodo died, besides that particular bird? It had no offspring, and neither did any of its very close relatives. But how close do relatives have to be to “count” here? Evolution has rendered this question problematic. Maybe a species too is a social reality or convention, but there is some debate about that.[7] Some would say the word species is really just shorthand for a particular collection of individuals and cannot ultimately be defined without some arbitrariness.

But what about something like love? To what does that word refer? Can we explain it away like we did unicorns? Is love a convention? I hope not. Can it be reduced to physical realities, such that the word is just a shorthand or placeholder for a more complex physical existence? I am leery of attempts to reduce such concepts to physical correlates. Based on a recent article in Frontiers in Human Neuroscience about fMRI images of the brain looking for love, a number of neuroscientists have concluded:

Reviews of these studies conclude that love is accompanied by significantly increased activation in brain regions such as the ventral tegmental area (VTA), medial insula, anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), hippocampus, nucleus accumbens (NAC), caudate nucleus, and hypothalamus. At the same time, deactivations can be found in the amygdala, prefrontal cortex (PFC), temporal poles, and temporo-parietal junction (TPJ; Zeki, 2007; de Boer et al., 2012; Diamond and Dickenson, 2012; Tarlaci, 2012). Cacioppo et al. (2012) have suggested that romantic love-related brain regions can be divided into subcortical and cortical brain networks where the former mediates reward, motivation, and emotion regulation, and the latter mainly supports social cognition, attention, memory, mental associations, and self-representation.[8]

Those who are more cautious in their language speak only about the correlations between some range of experience to which we have given a word like “love” and the brain activity that accompanies that experience. Others are not so cautious about identifying these very human and personal concepts with bits of matter. For example, Francis Crick pronounced (with all the authority bestowed on him for his scientific exploits) that “you, your joys and your sorrows, your memories and your ambitions, your sense of personal identity and free will, are in fact no more than the behavior of a vast assembly of nerve cells and their attendant molecules.”[9] Here there are two different sets of terms—one that is amenable to scientific treatment, like nerve cells and molecules; and the other, what we might call personal concepts like you, your sorrows, ambitions, free will, etc. Crick thinks the terms in this latter set are just silly names we have given to things we didn’t really understand and that once we do understand them we can see that they are nothing but the things more accurately named by the scientific language. I, however, want to claim that both sets of terms legitimately identify aspects of reality, which leads me to the next claim.

The Scientific and Personal Images are both Legitimate Re-Presentations

In a classic paper, mid-twentieth century philosopher Wilfred Sellars referred to these two different sets of terms as different pictures by which we have represented ourselves:

The philosopher is confronted not by one complex many-dimensional picture, the unity of which, such as it is, he must come to appreciate; but by two pictures of essentially the same order of complexity, each of which purports to be a complete picture of man-in-the-world, and which, after separate scrutiny, he must fuse into one vision.[10]

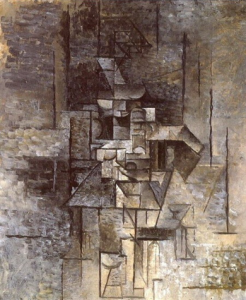

Developing the metaphor of pictures, we might think about these two sets of terms and the concepts they name as styles of painting. Picasso’s The Old Guitarist[11] from his blue period of expressionism, and his Guitariste[12] in the style of cubism are both representations of the same subject. Yet they look very different and could not be fused into one coherent image without a significant breach of artistic integrity. Each style intends to highlight or draw out different aspects of the thing it represents.

By analogy, a scientific description and a personal (or even theological) account of the nature of human beings may look very different, but that does not count against the legitimacy of either. What should be considered is whether the models are good representations in the “style” each intends. However, Sellars claimed that fusing these into one vision was the goal. How to do this? Typically, we attempt to reduce one of them to the other, and in our day and age it is the personal image that is reduced away. I claim next:

The Two Images or Discourses Cannot be Reduced to Each Other

The second of the books I commend as worthwhile reading on the topic of language, and specifically the limits of scientific language in describing all of reality, is Mary Midgley’s Are You An Illusion?[13] Midgley takes the reductivists to task, adopting Descartes’s strategy when, in his Meditations, he claimed that even if he was being deceived about everything else, it was still he who was being deceived. He must exist. Midgley wonders: if we have been deluded into thinking that there is a self, just what is it that is being deluded? Can we eliminate talk of selves and their intentions, free will, love, and wisdom? No, she says.

What are we to do with these two different sets of concepts that do not seem translatable into each other? Are they describing the same thing? Instead of artistic styles, Midgley uses a different metaphor, comparing these two ways of understanding a person to the information drawn from our different senses. An electrical discharge in the atmosphere might be understood by vision as a bolt of lightning, and by hearing as a clap of thunder. Vision and hearing are not perceiving two different events, but these senses detect different kinds of information about that one electrical discharge. And we cannot reduce or translate one of these into the other without losing something.[14] The implication is that the way of knowing we call “science” does not tell the whole story of the thing it describes. Instead, we have different language traditions—different discourses—that have developed over time to pick out different features of reality. Midgley notes:

The relation between the two subject matters needs then to be explicitly stated and thought about. But there is still no reason to expect that one of their messages will turn out to be real and the other illusory. These two languages are not rivals, competitors for a prize marked “reality.” They merely do different work. Their differences simply show that when we talk about the same topic, we are considering it from different angles and asking different questions. There need be no suspicion that either account is illusory unless we see something that really indicates fishiness.[15]

This dual view of humans is not without precedent. The early twentieth century Jewish philosopher Martin Buber claimed that “the world is two-fold for man in accordance with his two-fold attitude.”[16] He called these the “You-world” and the “It-world” depending on whether we treat our experiences as originating from a subject (a You) or an object (an It). He described our dual attitude toward other human beings as follows:

When I confront a human being as my You and speak the basic I-You to him, then he is no thing among things nor does he consist of things…. Even as a melody is not composed of tones, nor a verse of words, nor a statue of lines—one must pull and tear to turn a unity into a multiplicity—so it is with the human being to whom I say You. I can abstract from him the color of his hair or the color of his speech or the color of his graciousness; I have to do this again and again; but immediately he is no longer You.[17]

Here we have different aspects of the human experience that are amenable to different kinds of description. When we treat humans as objects, we put them under the microscope and explain their activities using the language of science. We do fMRI scans to see what their brains are doing and find causes. But when we treat them as subjects, we explain their actions by appealing to reasons.

The third book I will discuss is Rowan Williams’s The Edge of Words.[18] Based on his Gifford Lectures in 2013, it primarily considers the extent to which a kind of natural theology can be elaborated from our language itself. I will highlight two points for consideration from this very rich and rewarding book. Williams speaks of our language shifting register when we come up against the limits of what we describe and explain. We have language that is suitable for describing, say, the behavior of neurons, but at some point, in speaking of human behavior, we have to shift to speaking of intentions or will, and we find the neuron language is no longer suitable or sufficient. Williams develops a theory of constitutive language by claiming that language “creates a world, and so entails a constant losing and rediscovering of what is encountered.”[19] Language re-presents what is there, and so continually creates afresh “the life of what is perceived.”[20]

This brings me to a second point from Williams, which relates to the historical development of these language traditions. According to his analysis, to understand any particular utterance is to know what to say in response, to know how to “go on” in the conversation. He claims: “Rather than being a matter of gaining insight into a timeless mental content ‘behind’ or ‘within’ what is said, it is being able to exhibit the next step in a continuing pattern.”[21] That means that whatever we say about something must reckon with and reflect not only some external reality, but also what has already been said about it, along with how the world has already been represented by others. As a result, we find ourselves inescapably in a language tradition or discourse. But there is not just one possible thing to say next; the conversations could go off in different directions, explaining the development of these two different discourses, these two images we have of ourselves as subject and object. Understanding one aspect of a human takes us in the direction of what we can say about humans scientifically; but we can also re-present the human experience with “personal” terms like intention, love, and wisdom. To discount one of these discourses is to settle for just one perspective, a limited point of view. We will understand a human being more completely when we are involved in both conversations.

Briefly, in conclusion, if we stand in a tradition of conversation about wisdom, what do we say next? How do we “go on” in the conversation? First, this consideration of the role of language suggests that we remember that wisdom is part of the personal discourse. Wisdom is not a property of objects, but of subjects, and the collection of terms we have for describing and explaining subjects cannot be eliminated without massive loss. The reductive strategy of Crick might illuminate some aspects of human experience, but I am deeply skeptical of a science of wisdom that attempts to tell the whole story by reducing wisdom to the kinds of terms suitable for scientific explanation. Secondly, the constitutive role of language means that our conversation about wisdom contributes to what wisdom is and thereby contributes to the kind of beings we are. Since at least Socrates in the western philosophical tradition, and separately begun among the Hebrew people, humans have discussed wisdom and thereby created modes of life—ways of being—in which wisdom is recognized and enacted. Representing ourselves and our experience in such terms has had an effect, and we cannot go back and un-say these things that have contributed to the cognitive environment within which we attempt to understand ourselves. As Sellars notes: “if man had a radically different conception of himself he would be a radically different kind of man.”[22] So when we conceive of ourselves as having a potential for wisdom, we are a different kind of thing than if we did not. That has consequences and perhaps even the moral implication that we ought to continue the conversation about ourselves in ways that makes it possible for us to truly be Homo sapiens—the wise people.

JAMES STUMP is the Senior Editor at BioLogos, the organization founded by Francis Collins to show the compatibility of Christian theology and evolution. At BioLogos Jim is in charge of developing new content for the website and print materials, as well as curating existing content. His graduate training is in philosophy (MA, Northern Illinois University; PhD., Boston University). Among the books he has authored or edited are, Science and Christianity: An Introduction to the Issues (Wiley-Blackwell, 2017), Four Views on Creation, Evolution, and Intelligent Design (Zondervan, 2017), How I Changed My Mind About Evolution (InterVarsity Press, 2016), The Blackwell Companion to Science and Christianity (Wiley-Blackwell, 2012), and Christian Thought: A Historical Introduction (Routledge, 2010, 2016). His current scholarly project investigates the extent to which theories of language affect our understanding of the relationship between scientific and theological explanations.

References

[1] Ernst Cassirer, An Essay on Man (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1944), 25.

[2] Terrence Deacon, The Symbolic Species: The Co-evolution of Language and the Brain (New York: W. W. Norton, 1997).

[3] Charles Taylor, The Language Animal: The Full Shape of the Human Linguistic Capacity (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2016).

[4] Ibid., 6.

[5] Ibid., 28.

[6] Ibid., 33.

[7] Richard A. Richards, The Species Problem: A Philosophical Analysis (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

[8] Hongwen Song, et al., “Love-Related Changes in the Brain: A Resting-State Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study,” Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 9.71 (2015).

[9] Francis Crick, The Astonishing Hypothesis: The Scientific Search for the Soul (New York: Touchstone, 1995), 3.

[10] Wilfrid Sellars, Empiricism and the Philosophy of Mind (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1963), 4–5.

[11] Pablo Picasso—The Art Institute of Chicago and jacquelinemhadel.com, PD-US, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=31832131

[12] Pablo Picasso—http://www.pablo-ruiz-picasso.net/work-3193.php, PD-US, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=39013881

[13] Mary Midgley, Are You an Illusion? (London: Routledge, 2014).

[14] Ibid., 114.

[15] Ibid., 27–8.

[16] Martin Buber, I and Thou, translated by Walter Kaufmann (New York: Touchstone Books, 1970), 82.

[17] Ibid., 59.

[18] Rowan Williams, The Edge of Words: God and the Habits of Language (London: Bloomsbury, 2014).

[19] Ibid., 59–60.

[20] Ibid., 59.

[21] Ibid., 68.

[22] Sellars, “Philosophy and the Scientific Image of Man,” 6.

Bibliography

- Buber, Martin. I and Thou, translated by Walter Kaufmann. New York: Touchstone Books, 1970.

- Cassirer, Ernst. An Essay on Man. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1944.

- Crick, Francis. The Astonishing Hypothesis: The Scientific Search for the Soul. New York: Touchstone, 1995.

- Deacon, Terrence W. The Symbolic Species: The Co-evolution of Language and the Brain. New York: W.W. Norton, 1997.

- Midgley, Mary. Are You an Illusion? London: Routledge, 2014.

- Richards, Richard A. The Species Problem: A Philosophical Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Sellars, Wilfrid. “Philosophy and the Scientific Image of Man.” In Empiricism and the Philosophy of Mind. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1963.

- Song, Hongwen, et al. “Love-Related Changes in the Brain: A Resting-State Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study.” Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 9.71 (2015).

- Taylor, Charles. The Language Animal: The Full Shape of the Human Linguistic Capacity. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2016.

- Williams, Rowan. The Edge of Words: God and the Habits. London: Bloomsbury, 2014.