4

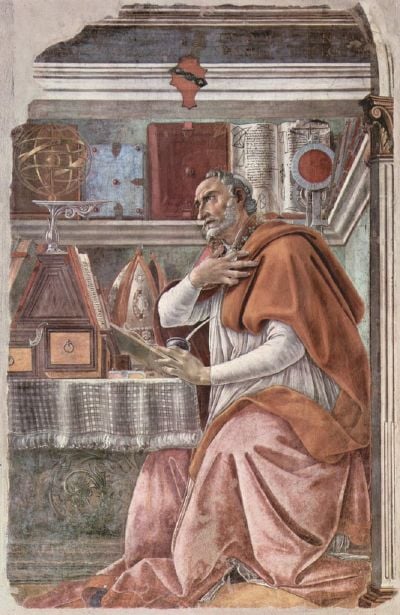

Augustine

Though Augustine’s mother was a Christian, his father was not. In his early life, Augustine rejected Christian teaching. Learning was very important to him, and he studied “that I might flourish in this world, and distinguish myself in the science of speech, which should get me honor amongst men, and deceitful riches!” (quoted in Smith, 156). Augustine’s education and early career was in philosophy and rhetoric, the art of persuasion and public speaking.

In 383 he moved to Rome, where he believed the best and brightest rhetoricians practiced. However, he was disappointed with the Roman schools, which he found apathetic. Manichaean friends introduced him to the prefect of the city of Rome, Symmachus, who had been asked to provide a professor of rhetoric for the imperial court at Milan. The young provincial won the job and headed north to take up his position in late 384. At age 30, Augustine had won the most visible academic chair in the Latin world, at a time when such posts gave ready access to political careers. However, he felt the tensions of life at an imperial court, lamenting one day as he rode in his carriage to deliver a grand speech before the emperor, that a drunken beggar he passed on the street had a less careworn existence than he did.

It was after this that he met Ambrose, a bishop, in Milan. Ambrose was a master of rhetoric like Augustine himself, but older and more experienced. Not only was Ambrose important in the faith community, but he was highly respected politically, as well. Ambrose believed that Christianity should be tied into the empire of Rome–essentially he wanted no separation between church and state. Prompted in part by Ambrose’s sermons, and partly by his own studies, in which he steadfastly pursued a quest for ultimate truth, Augustine renounced Manichaeism. It was during this time that Augustine began reading the the letters of Paul, which eventually led to his conversion in 386.

He then used all of his knowledge of rhetoric and skill in speaking to share the Christian faith. He believed that “since it was a Christian’s duty to spread the word of Jesus, it was also a Christian’s duty to learn to speak well” (Smith, 157). Augustine wrote prolifically, and, in addition to incorporating the style of Paul, his work is heavily influenced by Plato and Cicero. “Wedding his version of Platonism and Ciceronian theory with scripture, Augustine advanced a rhetorical theory to be used for teaching and converting while at the same time refuting the heretics and non-Christian philosophers such as neoplatonists” (Smith, 165).

- From Plato, Augustine gleaned the notion of the soul, the idea that truth comes through divine revelation, and the belief in universal truth.

- From Cicero comes Augustine’s focus on the study of language and memory, including the idea that the message is more important than the speaker and that rhetoric could and should be used for religious purposes.

- From the Bible, Augustine was influenced by St. Paul’s beliefs in predestination and Jesus’ style and concept of multiple audiences hearing the same message.

Augustine believed that there is only one truth, and the source of that truth is God. To him, that meant that only God can reveal the truth. Based on these beliefs, he thought that rhetoric should be used to carry the truth to an audience, who must then receive revelation to understand the message.

Augustine really forms the foundation of Christian teaching, and we still see his influence today in Christian theology.

Watch this overview of Augustine from Professor Mary Bauer :

Augustine’s Works

Augustine was one of the most prolific Latin authors, and the list of his works include apologetic works against the heresies of the Donatists, Manichaeans, Pelagians, and Arians; texts on Christian doctrine, notably “On Christian Doctrine” (De doctrina Christiana); exegetical works such as commentaries on Genesis, the Psalms, and Paul’s Epistle to the Romans; many sermons and letters; and the “Retractions” (Retractationes), a review of his earlier works which he wrote near the end of his life. Apart from those, Augustine is probably best known for his Confessions, which is a personal account of his earlier life, and for “The City of God” (De Civitate Dei), consisting of 22 books, which he wrote to restore the confidence of his fellow Christians, which was badly shaken by the sack of Rome by the Visigoths in 410.

Augustine: Account of His Own Conversion

Scholasticism

The work of Augustine serves as the foundation of two groups of scholars from the middle ages–the scholastics and the humanists.

After the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, Western Europe had entered the Middle Ages with great difficulties. Apart from depopulation and other factors, most classical scientific treatises of classical antiquity, written in Greek, had become unavailable. Philosophical and scientific teaching of the Early Middle Ages was based upon the few Latin translations and commentaries on ancient Greek scientific and philosophical texts that remained in the Latin West.

This scenario changed during the renaissance of the 12th century. The increased contact with Byzantium and with the Islamic world in Spain and Sicily, the Crusades, and the Reconquista allowed Europeans to seek and translate the works of Hellenic and Islamic philosophers and scientists, especially Aristotle. By 1200 there were reasonably accurate Latin translations of the main works of Aristotle, Euclid, Ptolemy, Archimedes, and Galen—that is, all the intellectually crucial ancient authors except Plato. Also, many of the medieval Arabic and Jewish key texts, such as the main works of Avicenna, Averroes, and Maimonides became available in Latin.

The rediscovery of the works of Aristotle allowed the full development of the new Christian philosophy and the method of scholasticism. The term came from the name “Schoolmen” (Latin scholasticus and Greek Scholastikos) given to Christian scholars who were devoted to learning and studied classical and biblical texts. These scholars wanted to reconcile the work of ancient philosophers with their Christian theology.

Scholasticism was the primary method of thought used in universities from 1100-1500. Scholastics believed in empiricism and supporting Roman Catholic doctrines through secular study, reason, and logic. Their focus was on finding the answers to the questions. They wanted to resolve any contradictions they found. They believed that logic could provide all the answers they sought. Thus, scholastics focused on dialectical reasoning and logic. Remember, Plato is the original source of the dialectic–a dialogue between two people with different points of view. Eventually, this became a process called disputation, which included a very specific process whose object was to increase knowledge.

- Lectio–read a piece critically and research everything related to it. question, a response, and a rebuttal.

- Quaestrio: Question– Write down differences and points of contention

- Diputation: Discussion/Debate–Look at meanings of words and eliminate contraditions

Foundations of Scholastic Theology

- God is real.

- It is possible to know God.

- God wants people to know Him.

- He has given people Revelation so that they might know Him.

- He has left clues throughout creation about Himself.

- Science and Theology are both ways of comprehending God.

- Theology interprets Revelation and tells people what to believe.

- Science interprets Creation to show how God does things.

Here’s a short video by Dr. Jordan Cooper discussing the theology of Scholaticism:

In general, the characteristics of Scholastic thought are the following:

- Harmony between reason and faith

- Aristotle is greater than Plato

- Men are divided into classes; therefore, different discourse is used for different classes.

- Rhetoric is for the ignorant; logic is for the educated

- Used Dialectical reasoning and disputation

- Reconciled contradictions and made careful distinctions

The story of “The Owl and the Nightingale” from the 12th/13th century provides an interesting look at the scholastic method.

Please watch this overview of Scholasticism from Christian Cuthbert:

Key Figures

Boethius (480-524)

Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius was a Roman senator, polymath, and a Christian philosopher of the sixth century who was instrumental in transmitting classical Greek logic to medieval Latin scholars by translating Aristotle’s work. Born into a high-ranking Christian Roman family and highly educated, including studying at Plato’s Academy, he served as an official for the kingdom of the Ostrogoths, but was later executed by King Theodoric the Great on suspicion of having conspired with the Byzantine Empire.

Boethius stated his intention to educate the West by translating all the works of Plato and Aristotle into Latin and adding commentaries; this effort was cut short, but his translations of Aristotle’s works on logic, together with his commentaries, remained the only works of Aristotle available to Latin scholars until the twelfth century. One of his students, Cassiodorus Senator, began the process of copying manuscripts, which preserved many texts. His commentary on the Isagoge by Porphyry, in which he discusses whether species are subsistent entities which would exist whether anyone thought of them, or whether they exist as ideas alone, underlay one of the most vocal controversies in medieval philosophy, the problem of universals. De Categoricis Syllogismis and Introductio ad Syllogismos Categoricos discussed categorical and hypothetical syllogisms.

His legacy includes textbooks on geometry, arithmetic, astronomy and music which were used throughout the Latin Middle Ages; commentaries on Aristotle, Porphyry and Cicero; essays on logic and four treatises applying logic to theological doctrines such as the Trinity and the relationship between God and Jesus Christ. Until the twelfth century, two of his translations were the only works of Aristotle available to Latin scholars. His most famous work, written in prison before his execution, is Consolation of Philosophy, which became one of the most influential philosophical books of medieval Europe and an inspiration for many later poets and authors.

Hugh of St. Victor (1096-1141)

Hugh of Saint Victor was an Augustinian monk and a leading theologian and writer on mystical theology. He wrote a history of arts in the middle ages. Like most scholastics, Hugh matched the style of discourse to the class of people. He believed that “Scripture…is the source par excellence…and theology…is the peak of philosophy and the perfection of truth…” In his work, he divides grammar (speaking without error), dialectic (argument that discovers truth), and rhetoric (persuading).

Hugh wrote many works from the 1120s until his death (Migne, Patrologia Latina contains 46 works by Hugh, and this is not a full collection), including works of theology (both treatises and sententiae), commentaries, mysticism, philosophy and the arts, and a number of letters and sermons.

Hugh was influenced by many people, but chiefly by Saint Augustine, especially in holding that the arts and philosophy can serve theology. In turn, he influenced others, including his student, Peter Abelard, and Thomas Aquinas.

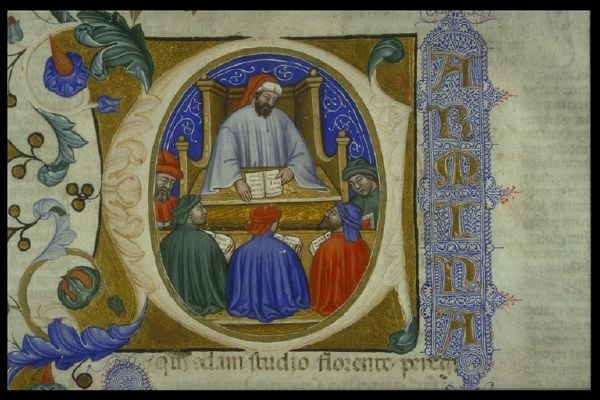

Peter Abelard (1079-April 21, 1142)

Pierre Abélard (in English, Peter Abelard) or Abailard (in English, Peter Abelard) or Abailard was a preeminent French scholastic philosopher, often referred to as the “Descartes of the twelfth century” due to his rationalist orientation, and regarded as a forerunner of Rousseau, Kant, and Lessing. He was one of the greatest logicians of the Middle Ages, and one of those who believed that ancient pagan philosophy was relevant to Christian thought.

He was one of the first to introduce the methods and ideas of Aristotle to Christian intellectuals, and he helped establish the scholastic tradition of using philosophy to provide a rationale for ecclesiastical doctrine. A formidable polemicist, he was rarely defeated in debate because of his keen intelligence, excellent memory, eloquence, and audacity. Abelard is regarded by later scholars as one of the founders of “nominalism.” He also anticipated Kant by arguing that subjective intention determined if not the moral character at least the moral value of human action. The story of his tragic love affair with his student, Héloïse has become a romantic legend.

Here’s a video discussing the famous love story of Abelard and Heloise:

The general importance of Abélard lies in his establishment of the scholastic tradition of using philosophy to give a formally rational expression to received ecclesiastical doctrine. Though his own particular interpretations may have been condemned, they were conceived in essentially the same spirit as the general scheme of thought afterwards elaborated in the thirteenth century with approval from the heads of the church. He initiated the ascendancy of the philosophical authority of Aristotle during the Middle Ages; before his time, Realism relied on the authority of Plato. Aristotle’s influence became firmly established in the half-century after Abélard’s death, when the completed Organon, and later all the other works of the Greek thinker, came to be known in the schools. Abelard contributed to the development of argumentative methods by adopting a method of inquiry called Sic et non (“Yes and no”), which presents two contradictory views of authority and highlights the points of disputes. This work highlights Abelard’s belief that doubting (or questioning) is an important part of faith.

Abelard’s Works

Sic et Non in the Public Domain from Medieval Sourcebooks

Among the multitudinous words of the holy Fathers some sayings seem not only to differ from one another but even to contradict one another. Hence it is not presumptuous to judge concerning those by whom the world itself will be judged, as it is written, “They shall judge nations” (Wisdom 3:8) and, again, “You shall sit and judge” (Luke 22:30). We do not presume to rebuke as untruthful or to denounce as erroneous those to whom the Lord said, “He who hears you hears me; he who despises you despises me” (Luke 10:26). Bearing in mind our foolishness we believe that our understanding is defective rather than the writing of those to whom the Truth Himself said, “It is not you who speak but the spirit of your Father who speaks in you” (Matthew 10:20). Why should it seem surprising if we, lacking the guidance of the Holy Spirit through whom those things were written and spoken, the Spirit impressing them on the writers, fail to understand them? Our achievement of full understanding is impeded especially by unusual modes of expression and by the different significances that can be attached to one and the same word, as a word is used now in one sense, now in another. Just as there are many meanings so there are many words. Tully says that sameness is the mother of satiety in all things, that is to say it gives rise to fastidious distaste, and so it is appropriate to use a variety of words in discussing the same thing and not to express everything in common and vulgar words….

We must also take special care that we are not deceived by corruptions of the text or by false attributions when sayings of the Fathers are quoted that seem to differ from the truth or to be contrary to it; for many apocryphal writings are set down under names of saints to enhance their authority, and even the texts of divine Scripture are corrupted by the errors of scribes. That most faithful writer and true interpreter, Jerome, accordingly warned us, “Beware of apocryphal writings….” Again, on the title of Psalm 77 which is “An Instruction of Asaph,” he commented, “It is written according to Matthew that when the Lord had spoken in parables and they did not understand, he said, ‘These things are done that it might be fulfilled which was written by the prophet Isaias, I will open my mouth in parables.’ The Gospels still have it so. Yet it is not Isaias who says this but Asaph.” Again, let us explain simply why in Matthew and John it is written that the Lord was crucified at the third hour but in Mark at the sixth hour. There was a scribal error, and in Mark too the sixth hour was mentioned, but many read the Greek epismo as gamma. So too there was a scribal error where “Isaias” was set down for “Asaph.” We know that many churches were gathered together from among ignorant gentiles. When they read in the Gospel, “That it might be fulfilled which was written by the prophet Asaph,” the one who first wrote down the Gospel began to say, “Who is this prophet Asaph?” for he was not known among the people. And what did he do? In seeking to amend an error he made an error. We would say the same of another text in Matthew. “He took,” it says, “the thirty pieces of silver, the price of him that was prized, as was written by the prophet Jeremias.” But we do not find this in Jeremias at all. Rather it is in Zacharias. You see then that here, as before, there was an error. If in the Gospels themselves some things are corrupted by the ignorance of scribes, we should not be surprised that the same thing has sometimes happened in the writings of later Fathers who are of much less authority….

It is no less important in my opinion to ascertain whether texts quoted from the Fathers may be ones that they themselves have retracted and corrected after they came to a better understanding of the truth as the blessed Augustine did on many occasions; or whether they are giving the opinion of another rather than their own opinion . . . or whether, in inquiring into certain matters, they left them open to question rather than settled them with a definitive solution….

In order that the way be not blocked and posterity deprived of the healthy labor of treating and debating difficult questions of language and style, a distinction must be drawn between the work of later authors and the supreme canonical authority of the Old and New Testaments. If, in Scripture, anything seems absurd you are not permitted to say, “The author of this book did not hold to the truth”–but rather that the codex is defective or that the interpreter erred or that you do not understand. But if anything seems contrary to truth in the works of later authors, which are contained in innumerable books, the reader or auditor is free to judge, so that he may approve what is pleasing and reject what gives offense, unless the matter is established by certain reason or by canonical authority (of the Scriptures ) ….

In view of these considerations we have undertaken to collect various sayings of the Fathers that give rise to questioning because of their apparent contradictions as they occur to our memory. This questioning excites young readers to the maximum of effort in inquiring into the truth, and such inquiry sharpens their minds. Assiduous and frequent questioning is indeed the first key to wisdom. Aristotle, that most perspicacious of all philosophers, exhorted the studious to practice it eagerly, saying, “Perhaps it is difficult to express oneself with confidence on such matters if they have not been much discussed. To entertain doubts on particular points will not be unprofitable.” For by doubting we come to inquiry; through inquiring we perceive the truth, according to the Truth Himself. “Seek and you shall find,” He says, “Knock and it shall be opened to you.” In order to teach us by His example He chose to be found when He was about twelve years old sitting in the midst of the doctors and questioning them, presenting the appearance of a disciple by questioning rather than of a master by teaching, although there was in Him the complete and perfect wisdom of God. Where we have quoted texts of Scripture, the greater the authority attributed to Scripture, the more they should stimulate the reader and attract him to the search for truth. Hence I have prefixed to this my book, compiled in one volume from the saying of the saints, the decree of Pope Gelasius concerning authentic books, from which it may be known that I have cited nothing from apocryphal books. I have also added excerpts from the Retractions of St. Augustine, from which it will be clear that nothing is included which he later retracted and corrected.

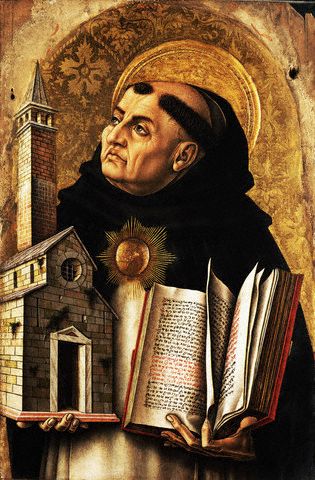

Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274)

Saint Thomas Aquinas, O.P. (also Thomas of Aquin, or Aquino; c. 1225 – March 7, 1274) was an Italian Roman Catholic priest in the Order of Preachers (more commonly known as the Dominican Order), a philosopher and theologian in the scholastic tradition, known as Doctor Angelicus, Doctor Universalis and Doctor Communis. He is the foremost classical proponent of natural theology, and the father of the Thomistic school of philosophy and theology. Aquinas persuaded the Catholic church to embrace the doctrine of Free Will and championed Aristotelian views. Unfortunately, this led to the conviction of Galileo and other scientists.

In Aquinas’s thought, the goal of human existence is union and eternal fellowship with God. Specifically, this goal is achieved through the beatific vision, an event in which a person experiences perfect, unending happiness by comprehending the very essence of God. This vision, which occurs after death, is a gift from God given to those who have experienced salvation and redemption through Christ while living on earth.

This ultimate goal carries implications for one’s present life on earth. Aquinas stated that an individual’s will must be ordered toward right things, such as charity, peace, and holiness. He sees this as the way to happiness. Aquinas orders his treatment of the moral life around the idea of happiness. The relationship between free will and goal is antecedent in nature “because rectitude of the will consists in being duly ordered to the last end [that is, the beatific vision].” Those who truly seek to understand and see God will necessarily love what God loves. Such love requires morality and bears fruit in everyday human choices.

Saint Thomas Aquinas is held in the Roman Catholic Church to be the model teacher for those studying for the priesthood (Code of Canon Law, Can. 252, §3). The work for which he is best-known is the Summa Theologica. One of the 33 Doctors of the Church, he is considered by many Roman Catholics to be the Catholic Church’s greatest theologian. Consequently, many institutions of learning have been named after him.

Here is an interesting video on the differences between Augustine and Aquinas: “Saint Augustine and Thomas Aquinas: the role of the State in Medieval Europe (video lecture)”:

Aquinas’ Works

Summa Theologica (1265-1275, unfinished)

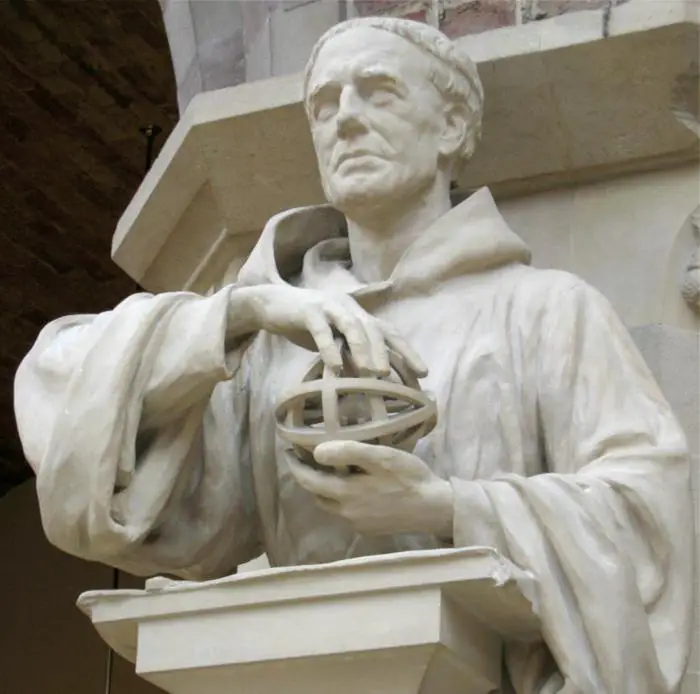

Bacon (1214-1292)

Roger Bacon (c. 1214 – 1294), was one of the most famous Franciscan friars of his time. He was an English philosopher who called for the reform of theological study, the study of foreign languages, and the integration of scientific study to the normal university curriculum. He placed considerable emphasis on empiricism, and has been presented as one of the earliest advocates of the modern scientific method in the West. HIs belief that data is needed to support conclusions helped to support scientists.

He was intimately acquainted with Aristotelian logic and philosophy, mathematics, and optics, much of it via the Arab world. Thus he served as a precursor for the reconciliation of science and religion through his call for academic development and reform of the Church in the study of scripture and science. Educated at Oxford, Bacon wrote about moral philosophy and believed that logic could not stand alone, beginning a revival of rhetoric.

The scientific training Bacon had received showed him the defects in existing academic debate. Aristotle was known only through poor translations, as none of the professors would learn Greek. The same was true of scripture. Physical science was not carried out by experiment in the Aristotelian way, but by arguments based on tradition.

Therefore, Bacon withdrew from the scholastic routine and devoted himself to languages and experimental research. The only teacher whom he respected was Petrus de Maharncuria Picardus, or “of Picardie” (probably the mathematician, Petrus Peregrinus of Picardie), who is perhaps the author of a manuscript treatise, De Magnete, contained in the Bibliotheque Imperiale at Paris. In the Opus Minus and Opus Tertium, he pours forth a violent tirade against Alexander of Hales, and another professor, who, he says, acquired his learning by teaching others, and adopted a dogmatic tone, which caused him to be received at Paris with applause as the equal of Aristotle, Avicenna, or Averroes.

Bacon was always an outspoken man who stated what he believed to be true and attacked those with whom he disagreed, which repeatedly caused him great trouble. In 1256 a new head of the scientific branch of the Franciscan order in England was appointed: Richard of Cornwall, with whom Bacon had strongly disagreed in the past. Before long, Bacon was transferred to a monastery in France, where for about ten years he could communicate with his intellectual peers only through writing.

Bacon wrote to the Cardinal Guy le Gros de Foulques, who became interested in his ideas and asked him to produce a comprehensive treatise. Bacon, being constrained by a rule of the Franciscan order against publishing works out of the order without special permission, initially hesitated. The cardinal later became Pope Clement IV and urged Bacon to ignore the prohibition and write the book in secret. Bacon complied and sent his work, the Opus Majus, a treatise on the sciences (grammar, logic, mathematics, physics, and philosophy), to the pope in 1267. It was followed in the same year by the Opus Minus (also known as Opus Secundum), a summary of the main thoughts from the first work. In 1268 he sent a third work, the Opus Tertium to the pope, who died the same year, apparently before even seeing the Opus Majus, although it is known that the work reached Rome.

In his writings, Bacon calls for a reform of theological study. He emphasizes that less emphasis should be placed on minor philosophical distinctions as in scholasticism, but instead the Bible itself should return to the center of attention and theologians should thoroughly study the languages in which their original sources were composed. He was fluent in several languages and lamented the corruption of the holy texts and the works of the Greek philosophers by numerous mistranslations and misinterpretations. Furthermore, he urged all theologians to study all sciences closely, and to add them to the normal university curriculum.

He possessed one of the most commanding intellects of his age, or perhaps of any, and, notwithstanding all the disadvantages and discouragements to which he was subjected, made many discoveries, and came near to many others. He rejected the blind following of prior authorities, both in theological and scientific study. His Opus Majus contains treatments of mathematics and optics, alchemy and the manufacture of gunpowder, the positions and sizes of the celestial bodies, and anticipates later inventions such as microscopes, telescopes, spectacles, flying machines and steam ships. Bacon studied astrology and believed that the celestial bodies had an influence on the fate and mind of humans. He also wrote a criticism of the Julian calendar, which was then still in use. He first recognized the visible spectrum in a glass of water, centuries before Sir Isaac Newton discovered that prisms could disassemble and reassemble white light.

Attributions

- Introductions for each section are written by Dr. Karen Palmer and licensed under CC BY NC SA. They reference information found in the following texts:

- Smith, Craig R. Rhetoric and Human Consciousness, 5th Edition. Waveland Press, 2017.

- Mabry, June. “Class 3 – The Universities and Scholasticism – The Era of Renaissance & Reformation.” The Era of Renaissance and Reformation, St. Anthony of Padua, 2020, sites.google.com/site/theeraofrenaissancereformation/the-universities-and-scholasticism.

- Pieper, Josef. “Scholasticism.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 14 Aug. 2019, www.britannica.com/topic/Scholasticism.

- “Scholasticism.” Scholasticism – By Movement / School – The Basics of Philosophy, www.philosophybasics.com/movements_scholasticism.html.

- V., Gabriela Briceño. “Scholasticism: What Is, about, History, Characteristics, Education, Economy, Works.” Euston96, 29 Sept. 2019, www.euston96.com/en/scholasticism/.

- “Augustine” from New World Encyclopedia licensed under CC BY SA.

- “Boethius” from New World Encyclopedia licensed under CC BY SA.

- “Aquinas” from New World Encyclopedia licensed under CC BY SA.

- “Hugh of St. Victor” licensed under CC BY SA.

- “Abelard” from New World Encyclopedia licensed under CC BY SA.

- “Bacon” from New World Encyclopedia licensed under CC BY SA.