6

As in earlier time periods, the way that rhetoric developed during the 17th-19th centuries was influenced by the events of the time. Reciprocally, the ways rhetoric was used influenced the development of history. You’ll find some interesting connections as the study and influence of rhetoric begins to span the oceans to impact our own history here in the US. As in previous time periods, we see a dichotomy between two different schools of thought. The scholastic focus on reason transitions into the Enlightenment, and the humanist resistance to that focus on reason inspires Romanticism.

Historical Events

The Enlightenment takes place in what some call the “long 18th century,” a time spanning from the mid-1600s to the late 1700s/early 1800s. Romanticism emerges at the end of the 1700s as scholars resist the Enlightenment’s focus on reason. Understanding the main events of this time period helps to create a framework for understanding the evolution of rhetoric during this time. Note the intersection of European and American history, as much of the rhetorical theory in Europe provided a background for the revolution stirring in the colonies.

The Industrial Revolution

The 18th century saw the emergence of the ‘Industrial Revolution’, the great age of steam, canals and factories that changed the face of the British economy forever.

Early 18th century British industries were generally small scale and relatively unsophisticated. Most textile production, for example, was centered on small workshops or in the homes of spinners, weavers and dyers: a literal ‘cottage industry’ that involved thousands of individual manufacturers. Such small-scale production was also a feature of most other industries, with different regions specializing in different products: metal production in the Midlands, for example, and coal mining in the North-East.

New techniques and technologies in agriculture paved the wave for change. Increasing amounts of food were produced over the century, ensuring that enough was available to meet the needs of the ever-growing population. A surplus of cheap agricultural labour led to severe unemployment and rising poverty in many rural areas. As a result, many people left the countryside to find work in towns and cities. So the scene was set for a large-scale, labour intensive factory system.

Steam and coal

Because there were limited sources of power, industrial development during the early 1700s was initially slow. Textile mills, heavy machinery and the pumping of coal mines all depended heavily on old technologies of power: waterwheels, windmills and horsepower were usually the only sources available.

Changes in steam technology, however, began to change the situation dramatically. As early as 1712 Thomas Newcomen first unveiled his steam-driven piston engine, which allowed the more efficient pumping of deep mines. Steam engines improved rapidly as the century advanced, and were put to greater and greater use. More efficient and powerful engines were employed in coal mines, textile mills, and dozens of other heavy industries. By 1800 perhaps 2,000 steam engines were eventually at work in Britain.

New inventions in iron manufacturing, particularly those perfected by the Darby family of Shropshire, allowed for stronger and more durable metals to be produced. The use of steam engines in coal mining also ensured that a cheap and reliable supply of the iron industry’s essential raw material was available: coal was now king.

Factories

The spinning of cotton into threads for weaving into cloth had traditionally taken place in the homes of textile workers. In 1769, however, Richard Arkwright patented his ‘water frame’, that allowed large-scale spinning to take place on just a single machine. This was followed shortly afterwards by James Hargreaves’ ‘spinning jenny’, which further revolutionized the process of cotton spinning.

The weaving process was similarly improved by advances in technology. Edmund Cartwright’s power loom, developed in the 1780s, allowed for the mass production of the cheap and light cloth that was desirable both in Britain and around the Empire. Steam technology would produce yet more change. Constant power was now available to drive the dazzling array of industrial machinery in textiles and other industries, which were installed up and down the country.

New ‘manufactories’ (an early word for ‘factory’) were the result of all these new technologies. Large industrial buildings usually employed one central source of power to drive a whole network of machines. Richard Arkwright’s cotton factories in Nottingham and Cromford, for example, employed nearly 600 people by the 1770s, including many small children, whose nimble hands made light-work of spinning. Other industries flourished under the factory system. In Birmingham, James Watt and Matthew Boulton established their huge foundry and metal works in Soho, where nearly 1,000 people were employed in the 1770s making buckles, boxes and buttons, as well as the parts for new steam engines.

Though not all factories were bad places to work, many were dismal and highly dangerous. Some factories were likened to prisons or barracks, where workers encountered harsh discipline enforced by factory owners. Many children were sent there from workhouses or orphanages to work long hours in hot, dusty conditions, and were forced to crawl through narrow spaces between fast-moving machinery. A working day of 12 hours was not uncommon, and accidents happened frequently.

Transport

The growing demand for coal after 1750 revealed serious problems with Britain’s transport system. Though many mines stood close to rivers or the sea, the shipping of coal was slowed down by unpredictable tides and weather. Because of the growing demand for this essential raw material, many mine owners and industrial speculators began financing new networks of canals, in order to link their mines more effectively with the growing centers of population and industry.

The early canals were small but highly beneficial. In 1761, for example, the Duke of Bridgewater opened a canal between his colliery at Worsley and the rapidly growing town of Manchester. Within weeks of the canal’s opening the price of coal in Manchester halved. Other canal building schemes were quickly authorized by Acts of Parliament, in order to link up an expanding network of rivers and waterways. By 1815, over 2,000 miles of canals were in use in Britain, carrying thousands of tonnes of raw materials and manufactured goods by horse-drawn barge.

Most roads were in a terrible state early in this period. Many were poorly maintained and even major routes flooded during the winter. Journeys by stagecoach were long and uncomfortable. London in particular suffered badly when wagons and carts were bogged down in poor conditions and were left unable to deliver food to markets. Faced with these difficulties, local authorities applied for ‘Turnpike Acts’ that allowed for new roads to be constructed, paid for out of tolls placed on passing traffic. New techniques in road construction, developed by pioneering engineers such as John McAdam and Thomas Telford, led to the great ‘road boom’ of the 1780s.

The improvements achieved by 18th century road builders were breathtaking. By the 1830s, the stagecoach journey from London to Edinburgh took just two days, compared to nearly two weeks only half a century before.

The church in the 18th century by Ryan Reeves:

18th Century Warfare by Crash Course

Additional Resources:

- Overview of European history from Brittanica

- Overview of American history from Brittanica

- Searchable timeline of the 18th century from George Mason University

The Enlightenment (AKA The Age of Reason)

Introduction

“The desire of being believed, the desire of persuading, of leading and directing other people, seems to be one of the strongest of all our natural desires. It is, perhaps, the instinct on which is founded the faculty of speech, the characteristic faculty of human nature.” Adam Smith (1723-1790)

The Scholastics emphasis of mind over soul is heightened as the emergence of epistemology, the study of how the human mind works and how it knows, inspires rhetoricians to apply the newly developed field of psychology to study how people learn and communicate. The Enlightenment’s emphasis on reason shaped philosophical, political and scientific discourse from the late 17th to the early 19th century.

The Enlightenment – the great ‘Age of Reason’ – is defined as the period of rigorous scientific, political and philosophical discourse that characterized European society during the ‘long’ 18th century: from the late 17th century (around 1685) to the ending of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815. This was a period of huge change in thought and reason, particularly in science, philosophy, and politics. As people began to question authority, centuries of custom and tradition were brushed aside in favor of exploration, individualism, tolerance and scientific endeavor, which, in tandem with developments in industry and politics, witnessed the emergence of the ‘modern world’.

Held by© Trustees of the British Museum

This Derby porcelain figurine of the radical politician John Wilkes poses nonchalantly among symbols of English liberty. The plinth upon which he leans has two scrolls, one inscribed ‘Magna Carta’ and the other ‘Bill of Rights’; at his feet a cherub holds a liberty cap and a treatise on government by John Locke.

The Emergence of ‘Reason’

The roots of the Enlightenment can be found in the turmoil of the English Civil Wars. With the re-establishment of a largely unchanged autocratic monarchy, first with the restoration of Charles II in 1660 and then the ascendancy of James II in 1685, leading political thinkers began to reappraise how society and politics could (and should) be better structured. Movements for political change resulted in the Glorious Revolution of 1688/89, when William and Mary were installed on the throne as part of the new Protestant settlement.

The Bill of Rights

The ancient civilizations of Greece and Rome were revered by enlightened thinkers, who viewed these communities as potential models for how modern society could be organized. Many commentators of the late 17th century were eager to achieve a clean break from what they saw as centuries of political tyranny, in favor of personal freedoms and happiness centered on the individual. Chief among these thinkers was philosopher and physician John Locke, whose Two Treatises of Government (published in 1689) advocated a separation of church and state, religious toleration, the right to property ownership, and a contractual obligation on governments to recognize the innate ‘rights’ of the people.

Locke believed that reason and human consciousness were the gateways to contentment and liberty, and he demolished the notion that human knowledge was somehow pre-programmed and mystical. Locke’s ideas reflected the earlier but equally influential works of Thomas Hobbes, which similarly advocated new social contracts between the state and civil society as the key to unlocking personal happiness for all.

Concurrent movements for political change also emerged in France during the early years of the 18th century. The writings of Denis Diderot, for example, linked reason with the maintenance of virtue and its ability to check potentially destructive human passions. Similarly, the profoundly influential works of Jean-Jacques Rousseau argued that man was born free and rational, but was enslaved by the constraints imposed on society by governments. True political sovereignty, he argued, always remained in the hands of the people if the rule of law was properly maintained by a democratically endorsed government: a radical political philosophy that came to influence revolutionary movements in France and America later in the century.

Scientific revolution

These new enlightened views of the world were also encapsulated in the explosion of scientific endeavor that occurred during the 18th century. Instead of through divine revelation of universal truth, intellectuals believed that knowledge came through experience. With the rapid expansion of print culture from around 1700, and increasing levels of literacy, details of experimentation and discovery were eagerly consumed by the reading public.

This growth of ‘natural philosophy’ (the term ‘science’ was only coined later in the 18th century) was underpinned by the application of rational thought and reason to scientific enquiry; first espoused by Francis Bacon in the early 1600s, this approach built on the earlier work of Copernicus and Galileo dating from the medieval period. Scientific experimentation (with instrumentation) was used to shed new light on nature and to challenge superstitious interpretations of the living world, much of which had been deduced from uncritical readings of historical texts.

View images from this item (2) Usage terms Public Domain

At the forefront of the scientific revolution stood Sir Isaac Newton, whose achievements in mathematics and physics revolutionized the contemporary view of the natural world. Born in 1643, Newton demonstrated a talent for mathematical theory at Trinity College, Cambridge, where his astonishingly precocious abilities led to his appointment as professor of mathematics at the age of just 26. Among Newton’s weighty catalogue of investigations were his treatises on optics, gravitational forces and mechanics (most famously encapsulated in his Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy, first published in 1687), all grounded in empirical experimentation as a way to demystify the physical world.

The discoveries of Sir Isaac Newton were complemented by those of a host of equally dazzling mathematicians, astronomers, chemists and physicists (Robert Hooke and Robert Boyle, for example), many of whom were members of the Royal Society (founded in 1660, and active today). Yet it was Newton’s empirical approach to science that remained particularly influential.

The pursuit of rational scientific knowledge was never the preserve of an educated elite. As well as fertilizing a huge trade in published books and pamphlets, scientific investigation created a buoyant industry in scientific instruments, many of which were relatively inexpensive to buy and therefore available to the general public. Manufacturers of telescopes, microscopes, barometers, air pumps and thermometers prospered during the 18th century, particularly after 1750 when the names of famous scientific experimenters became household names: Benjamin Franklin, Joseph Priestley, William Herschel and Sir Joseph Banks, for example.

Encyclopedias, grammars, and dictionaries became something of a craze in this period, helping to demystify the world in empirical terms. People believed that everything could and should be catalogued.

Secularization and the impact on religion

Religion and personal faith were also subject to the tides of reason evident during the 18th century. Personal judgements on matters of belief were actively debated during the period, leading to scepticism, if not bold atheism, among an enlightened elite. Others argued against this idea. Andrew Baxter, for example, argued that all matter is inherently inactive, and that the soul and an omnipotent divine spirit are the animating principles of all life. In making this argument, Baxter rejected the beliefs of more atheistic and materialist thinkers such as Thomas Hobbes and Baruch Spinoza.

These new views on religion led to increasing fears among the clergy that the Enlightenment was ungodly and thus harmful to the moral well-being of an increasingly secular society. With church attendance in steady decline throughout the 1700s, evidence of increasing agnosticism (the belief that true knowledge of God could never be fully gained) and a rejection of some scriptural teachings was close at hand. Distinct anti-clericalism (the criticism of church ministers and rejection of religious authority) also emerged in some circles, whipped up by the musings of ‘deist’ writers such as Voltaire, who argued that God’s influence on the world was minimal and revealed only by one’s own personal experience of nature.

Though certainly a challenge to accepted religious beliefs, the impulse of reason was considered by other contemporary observers to be a complement rather than a threat to spiritual orthodoxy: a means by which (in the words of John Locke) the true meaning of Scripture could be unlocked and ‘understood in the plain, direct meaning of the words and phrases’. Though difficult to measure or quantify, Locke believed that ‘rational religion’ based on personal experience and reflection could nevertheless still operate as a useful moral compass in the modern age.

New personal freedoms within the orbit of faith were extended to the relationship between the Church and state. In England, the recognition of dissenting religions was formalized by legislation, such as the 1689 Act of Toleration which permitted freedom of worship to Nonconformists (albeit qualified by allegiances to the Crown). Later, political emancipation for Roman Catholics – who were allowed new property rights – also reflected an enlightened impulse among the political elite: such measures sometimes created violent responses from working people. In 1780, for example, London was convulsed by a week of rioting in response to further freedoms granted to Catholics: a sign, perhaps, of how the enlightened thinking of politicians could diverge sharply from the sentiments of the humble poor.

Usage terms Public Domain

Political freedoms, contracts and rights

Public debates about what qualified as the best forms of government were heavily influenced by enlightened ideals, most notably Rousseau’s and Diderot’s notions of egalitarian freedom and the ‘social contract’. By the end of the 18th century most European nations harbored movements calling for political reform, inspired by radical enlightened ideals which advocated clean breaks from tyranny, monarchy and absolutism.

Late 18th-century radicals were especially inspired by the writings of Thomas Paine, whose influence on revolutionary politics was felt in both America and France. Born into humble beginnings in England in 1737, by the 1770s Paine had arrived in America where he began agitating for revolution. Paine’s most radical works, The Rights of Man and later The Age of Reason (both successful best-sellers in Europe), drew extensively on Rousseau’s notions of the social contract. Paine reserved particular criticism for the hereditary privileges of ruling elites, whose power over the people, he believed, was only ever supported through simple historical tradition and the passive acceptance of the social order among the common people.

Similarly, German philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) pointed towards the ‘laziness and Cowardice’ of the people to explain why ‘a large part of mankind gladly remain minors all their lives’, and spoke of reasoned knowledge gained from sensual experience as a means of achieving genuine freedom and equality.

Though grounded in a sense of outrage at social and economic injustice, the political revolutions of both America (1765 to 1783) and France (1789 to 1799) can thus be fairly judged to have been driven by enlightened political dogma, which criticized despotic monarchies as acutely incompatible with the ideals of democracy, equality under the rule of law and the rights to property ownership. These new movements for political reform argued in favor of protecting certain inalienable natural rights that some enlightened thinkers believed were innate in all men (though rarely in women as well): in the freedom of speech and protection from arbitrary arrest, for example, later enshrined in the American Constitution.

However, for other observers (particularly in Britain) the violent extremes of the French Revolution proved incompatible with enlightened thought. Many saw the extremes of revolution as a counterpoint to any true notion of ‘reason’. British MP Edmund Burke, for example, wrote critically of the ‘fury, outrage and insult’ he saw embedded in events across the Channel, and urged restraint among Britain’s own enlightened political radicals.

Political philosopher David Hume also warned of the dangers he perceived in the headlong pursuit of liberty for all. An ill-educated and ignorant crowd, argued Hume, was in danger of running into violence and anarchy if a stable framework of government was not maintained through the consent of the people and strong rule of law. Governments, he believed, could offer a benign presence in people’s lives only when moderated by popular support, and he therefore offered the extension of the franchise as a counterbalance to the strong authority of the state.

The end of the Enlightenment?

The outcomes of the Enlightenment were thus far-reaching and, indeed, revolutionary. By the early 1800s a new ‘public sphere’ of political debate was evident in European society, having emerged first in the culture of coffee-houses and later fueled by an explosion of books, magazines, pamphlets and newspapers (the new ‘Augustan’ age of poetry and prose was coined at the same time). Secular science and invention, fertilized by a spirit of enquiry and discovery, also became the hallmark of modern society, which in turn propelled the pace of 18th-century industrialization and economic growth.

Individualism – the personal freedoms celebrated by Locke, Hume, Adam Smith, Voltaire and Kant – became part of the web of modern society that trickled down into 19th-century notions of independence, self-help and liberalism. Representative government on behalf of the people was enshrined in new constitutional arrangements, characterized by the slow march towards universal suffrage in the 1900s.

Evidence of the Enlightenment thus remains with us today: in our notions of free speech, our secular yet religiously tolerant societies, in science, the arts and literature: all legacies of a profound movement for change that transformed the nature of society forever.

Overview of the Enlightenment from AHS :

Rhetoric of the Enlightenment

The Enlightenment had some key impacts on the way people communicated, especially in the ways in which rhetoric was applied.

The Elocutionary Movement

- The five Canons of Rhetoric (invention, arrangement, style, memory, and delivery) once again became the foundation of rhetorical study.

- Communication was divided into different categories. The Belles Lettres expanded rhetoric into a study of history, poetry, and language. With an emphasis on the appreciation of texts, the rules of classical rhetoric were used to critique literature.

- Communicators called for a plain style of speech that used plain language. They believed that communication should be accessible to all.

- Bacon’s theory of psychology was used as a means to appeal to the mental faculties for the purposes of persuasion.

- The elocution movement focused on delivery, correct pronunciation, and non-verbal appeals. A person’s speech was an indication of their class and education. So, by improving their speech, a person could increase the likelihood of being heard and believed.

Rhetoric and American Independence from Dr. Jerome Mahaffey:

https://youtube.com/watch?v=dGZj5hQVKtQ

Key Figures

Descartes (1596-1650)

René Descartes was a French philosopher, mathematician, and scientist. One of the most notable intellectual figures of the Dutch Golden Age, Descartes is also widely regarded as one of the founders of modern philosophy. He thought that everything a person believes should be proved beyond a reasonable doubt. Reason is the most important thing because the senses can be fooled.

Many elements of Descartes’s philosophy have precedents in late Aristotelianism, the revived Stoicism of the 16th century, or in earlier philosophers like Augustine. In his natural philosophy, he differed from the schools on two major points: first, he rejected the splitting of corporeal substance into matter and form; second, he rejected any appeal to final ends, divine or natural, in explaining natural phenomena. In his theology, he insists on the absolute freedom of God’s act of creation. In the opening section of the Passions of the Soul, an early modern treatise on emotions, Descartes goes so far as to assert that he will write on this topic “as if no one had written on these matters before.”

He laid the foundation for 17th-century continental rationalism. Descartes was well-versed in mathematics as well as philosophy, and he contributed greatly to science as well. Descartes’s influence in mathematics is equally apparent; the Cartesian coordinate system was named after him. He is credited as the father of analytical geometry—used in the discovery of infinitesimal calculus and analysis. Descartes was also one of the key figures in the Scientific Revolution.

Descartes’ Work:

Francis Bacon (1561-1626)

Francis Bacon worked for the queen and used rhetoric to urge the country to go war. He identified three ways of learning: fantastical (myths), contentious (unproven propositions), and delicate (humanists who did not do original research). Bacon invented the term “induction.”

Influenced by Aristotle, Augustine, and Ramus, Bacon believed that the use of rhetoric or imagination could defeat an argument of pure reason. He also believed that language has been corrupted by idols of the tribe (social group/culture), den (home/family), marketplace (popularity), and theater (past theology). This psychological theory would influence the rhetoric of the Enlightenment.

Bacon’s Work

Excerpt from Bacon’s Advancement of Learning

John Locke (1632-1704)

Locke was a Puritan who studied medicine and philosophy. He wrote the bill of rights for William III and Mary II. Locke endorsed the scientific method and believed that the mind is the center of the universe. He believed that the mind categorizes knowledge. He reasoned that the mind could not possibly hold all the information it does unless it was categorized. This was called the Doctrine of Abstraction. For example, our concept of sky blue is built upon our concept of blue, which is built upon our concept of color.

According to Locke, rhetoric applies reason to move the will. He was a proponent of family values, equality, liberty, and consensual government. In fact, he believed that the role of government is to protect the basic rights of every human being of life, liberty, and property.

Locke’s Work

An Essay Concerning Human Understanding

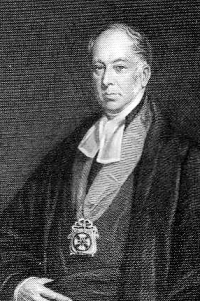

George Campbell (1719-1796)

Rev Prof George Campbell (25 December 1719 – 6 April 1796) was a figure of the Scottish Enlightenment, known as a philosopher, minister, and professor of divinity. Campbell was primarily interested in rhetoric, since he believed that its study would enable his students to become better preachers.

George Campbell ascertained that the human mind is separated into various faculties that serve the purpose of dictating moral reasoning. To his reasoning moral reasoning was a hierarchal system initiated by individual understanding of a given situation and moves on through imagination and personal desire. Campbell was clear that there were seven circumstances involved in a person’s decision to act on their impulses as described by The Rhetoric of Western Thought. The first is probability, the second is plausibility, the third is importance, the fourth is proximity of time, the fifth is connection, the sixth is relation, and the last is interest in the consequences. All of which play a major role in the manner in which a person operates.

Throughout Campbell’s literary career, he focused on enlightened concerns such as rhetoric, taste, and genius—perhaps a result of his time in the Aberdeen Philosophical Society. His attempt to align rhetoric within the sphere of psychology resulted from Francis Bacon’s survey of the structure and purpose of knowledge. The Philosophy of Rhetoric illustrates the influence of Bacon’s inductive methodology, but also scientific investigation—two major concerns of the Enlightenment.

As well, Campbell’s appeal to natural evidences was a similarity in process shared by most of the great minds of the Enlightenment. This is seen throughout his writing, with particular emphasis on placing methodology before doctrine, critical inquiry before judgment, and his application of tolerance, moderation, and improvement.

He argued that, if reason is not enough, there must be something outside of human experience that is the source of truth. He built a theory of argument based on data of experience, analogy, testimony, and probability and was determined to show that rhetoric is useful in the world, especially in preaching. Influenced by Cicero, he believed that “The ultimate task of rhetoric is to enlighten the understanding, to awaken the memory, to engage the imagination and to arouse the passions to influence the will to action or belief ” (Smith, 256).

Campbell’s Work

In his book, The Philosophy of Rhetoric, the philosopher states four types of evidence that goes into reasoning. The first one is that reasoning comes from experience and how past experiences shape our sense of reason for present, and future reasoning. The second type of evidence is analogy, to analyze a situation we are able to get more of an understanding and view what needs to be done in the future to better an outcome. The third type of evidence is testimony. Testimony has to deal with written or oral communication. The very last is calculations of chances. Knowing that chance is not predictable a person can assume and use reason when it comes to other certain types of happenings.

Richard Whately (1787-1863)

Richard Whately was an English academic, rhetorician, logician, philosopher, economist, and theologian who also served as Archbishop of Dublin. He was a prolific author, a flamboyant character, and one of the first reviewers to recognize the talents of Jane Austen.

He claimed that logic is the only province of rhetoric, which means rhetoric is the center of rational thought. Influenced by Cicero, Aristotle, and Campbell, he believed that God gave man reason so they could understand Him and thought every Christian should understand argumentation to share their faith. He warned about making assumptions about the audience because what we assume the audience believes may not be accurate.

Whately developed a new way to open speeches (called proems), that most writing students might recognize as a hook. For example, the speaker could explain how the information relates to the audience, surprise the audience, or tell a story.

- Introduction Inquisitive: connect topic to the audience

- Introduction paradoxical: focus on the improbable

- Introduction Corrective: addresses a misunderstanding or misrepresentation

- Introduction preparatory: background information

- Narrative introduction: story or event

He believed that speakers should use a natural style instead of dramatic speaking.

Whately’s Work

Other Notable Enlightenment Figures

- Alexander Bain (1818-1903): A Scottish philosopher who wrote books on grammar and rhetoric, including a book on how to apply logic to the natural sciences. Advanced the study of psychology.

- Immanuel Kant (1724-1804):Prussian philosopher who believed in human autonomy. Argues that “human understanding is the source of the general laws of nature that structure all our experience.” (IEP)

- Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770-1831): German historian and scholar who used dialectic to explain history.

Additional Resources:

- Here is an interesting resource on The American Enlightenment from the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. It’s important to understand how the intellectual movements in Europe impacted thought in the US, as well.

Romanticism (1798-1832)

“…figures of thought, if properly fashioned by careful word choice, [can] fascinate the mind and thereby hold attention or move the soul” (Vico as quoted by Smith, 242).

The Romantic movement, which favored the soul over the mind, is an extension of humanism. Beginning in the late 16th century, the Baroque era, which was spurred on through the Catholic Church’s emphasis on “realism, emotionalism, spirtualism and contrasts in light and dark” coincides with much of the Enlightenment (Smith, 238). The Jesuits believed that the background for a sermon enhanced its meaning and its effectiveness, influencing them to build ornate altars in churches that appealed to all five senses. In rhetoric, the “baroque rhetors sought to overwhelm their audiences with intense images that appealed to the senses” (Smith, 238).

Today the word ‘romantic’ evokes images of love and sentimentality, but the term ‘Romanticism’ has a much wider meaning. It covers a range of developments in art, literature, music and philosophy, spanning the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

In 1762 Jean-Jacques Rousseau declared in The Social Contract: ‘Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains.’ During the Romantic period major transitions took place in society, as dissatisfied intellectuals and artists challenged the Establishment. In England, the Romantic poets were at the very heart of this movement. They were inspired by a desire for liberty, and they denounced the exploitation of the poor. There was an emphasis on the importance of the individual; a conviction that people should follow ideals rather than imposed conventions and rules.

The Romantics renounced the rationalism and order associated with the preceding Enlightenment era, stressing the importance of expressing authentic personal feelings. They had a real sense of responsibility to their fellow men: they felt it was their duty to use their poetry to inform and inspire others, and to change society.

Age of Revolutions

When reference is made to Romantic verse, the poets who generally spring to mind are William Blake (1757-1827), William Wordsworth (1770-1850), Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772-1834), George Gordon, 6th Lord Byron (1788-1824), Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822) and John Keats (1795-1821). These writers had an intuitive feeling that they were ‘chosen’ to guide others through the tempestuous period of change.

This was a time of physical confrontation; of violent rebellion in parts of Europe and the New World. Conscious of anarchy across the English Channel, the British government feared similar outbreaks. The early Romantic poets tended to be supporters of the French Revolution, hoping that it would bring about political change; however, the bloody Reign of Terror shocked them profoundly and affected their views. In his youth William Wordsworth was drawn to the Republican cause in France, until he gradually became disenchanted with the Revolutionaries.

The Imagination

The Romantics were not in agreement about everything they said and did: far from it! Nevertheless, certain key ideas dominated their writings. They genuinely thought that they were prophetic figures who could interpret reality. Intuition, instinct, and feelings were more important than logic alone.

In fact, the Romantics highlighted the healing power of the imagination because they truly believed that it could enable people to transcend their troubles and their circumstances. Their creative talents could illuminate and transform the world into a coherent vision, to regenerate mankind spiritually. In A Defence of Poetry (1821), Shelley elevated the status of poets: ‘They measure the circumference and sound the depths of human nature with a comprehensive and all-penetrating spirit…’. He declared that ‘Poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world’. This might sound somewhat pretentious, but it serves to convey the faith the Romantics had in their poetry.

The Marginalized and Oppressed

Romantics were concerned with the individual. They believed that every individual was important and that people should be unique. They should be bold and experiment, rather than following the rules. For Romantics, poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings to reflect the journey and development of that self.

Wordsworth was concerned about the elitism of earlier poets, whose highbrow language and subject matter were neither readily accessible nor particularly relevant to ordinary people. He maintained that poetry should be democratic; that it should be composed in ‘the language really spoken by men’ (Preface to Lyrical Ballads [1802]). For this reason, he tried to give a voice to those who tended to be marginalized and oppressed by society: the rural poor; discharged soldiers; ‘fallen’ women; the insane; and children.

Blake was radical in his political views, frequently addressing social issues in his poems and expressing his concerns about the monarchy and the church. His poem ‘London’ draws attention to the suffering of chimney-sweeps, soldiers and prostitutes.

Children, Nature, and the Sublime

For the world to be regenerated, the Romantics said that it was necessary to start all over again with a childlike perspective. They believed that children were special because they were innocent and uncorrupted, enjoying a precious affinity with nature.

Romantic verse was suffused with reverence for the Nature and the natural world. To them, nature represented the divine imagination. In Coleridge’s ‘Frost at Midnight’ (1798) the poet hailed nature as the ‘Great universal Teacher!’ Recalling his unhappy times at Christ’s Hospital School in London, he explained his aspirations for his son, Hartley, who would have the freedom to enjoy his childhood and appreciate his surroundings. The Romantics were inspired by the environment, and they encouraged people to venture into new territories – both literally and metaphorically. In their writings they made the world seem a place with infinite, unlimited potential.

![Samuel Taylor Coleridge, A Walking Tour of Cumbria [folio: 3v-4r]](https://www.bl.uk/britishlibrary/~/media/bl/global/dl%20romantics%20and%20victorians/collection-items-more/c/o/l/coleridge-samuel_taylor-samuel-g70000-64.jpg?w=608&h=342&hash=C1248C6937D555DBBBF23D16FFA6A890)

Usage terms Public Domain

A key idea in Romantic poetry is the concept of the sublime. This term conveys the feelings people experience when they see awesome landscapes, or find themselves in extreme situations which elicit both fear and admiration. For example, Shelley described his reaction to stunning, overwhelming scenery in the poem ‘Mont Blanc’ (1816).

In his 1757 essay, the philosopher Edmund Burke discusses the attraction of the immense, the terrible and the uncontrollable. The work had a profound influence on the Romantic poets.

Romantics saw Symbolism and Myths as the human equivalent to nature’s language. Symbols and myths were seen as universal and, because they could simultaneously mean multiple things, they were seen as superior.

The Second-generation Romantics

Blake, Wordsworth and Coleridge were first-generation Romantics, writing against a backdrop of war. Wordsworth, however, became increasingly conservative in his outlook: indeed, second-generation Romantics, such as Byron, Shelley and Keats, felt that he had ‘sold out’ to the Establishment. In the suppressed Dedication to Don Juan (1819-1824) Byron criticized the Poet Laureate, Robert Southey, and the other ‘Lakers’, Wordsworth and Coleridge (all three lived in the Lake District). Byron also vented his spleen on the English Foreign Secretary, Viscount Castlereagh, denouncing him as an ‘intellectual eunuch’, a ‘bungler’ and a ‘tinkering slavemaker’ (stanzas 11 and 14). Although the Romantics stressed the importance of the individual, they also advocated a commitment to mankind. Byron became actively involved in the struggles for Italian nationalism and the liberation of Greece from Ottoman rule.

Notorious for his sexual exploits, and dogged by debt and scandal, Byron left Britain in 1816. Lady Caroline Lamb famously declared that he was ‘Mad, bad and dangerous to know.’ Similar accusations were pointed at Shelley. Nicknamed ‘Mad Shelley’ at Eton, he was sent down from Oxford for advocating atheism. He antagonized the Establishment further by his criticism of the monarchy, and by his immoral lifestyle.

Female Poets

Female poets also contributed to the Romantic movement, but their strategies tended to be more subtle and less controversial. Although Dorothy Wordsworth (1771-1855) was modest about her writing abilities, she produced poems of her own; and her journals and travel narratives certainly provided inspiration for her brother. Women were generally limited in their prospects, and many found themselves confined to the domestic sphere; nevertheless, they did manage to express or intimate their concerns. For example, Mary Alcock (c. 1742-1798) penned ‘The Chimney Sweeper’s Complaint’. In ‘The Birth-Day’, Mary Robinson (1758-1800) highlighted the enormous discrepancy between life for the rich and the poor. Gender issues were foregrounded in ‘Indian Woman’s Death Song’ by Felicia Hemans (1793-1835).

The Gothic

Reaction against the Enlightenment was reflected in the rise of the Gothic novel. The most popular and well-paid 18th-century novelist, Ann Radcliffe (1764–1823), specialized in ‘the hobgoblin-romance’. Her fiction held particular appeal for frustrated middle-class women who experienced a vicarious frisson of excitement when they read about heroines venturing into awe-inspiring landscapes. She was dubbed ‘Mother Radcliffe’ by Keats, because she had such an influence on Romantic poets. The Gothic genre contributed to Coleridge’s Christabel (1816) and Keats’s ‘La Belle Dame Sans Merci’ (1819). Mary Shelley (1797-1851) blended realist, Gothic and Romantic elements to produce her masterpiece Frankenstein (1818), in which a number of Romantic aspects can be identified. She quotes from Coleridge’s Romantic poem The Rime of the Ancyent Marinere. In the third chapter Frankenstein refers to his scientific endeavors being driven by his imagination. The book raises worrying questions about the possibility of ‘regenerating’ mankind; but at several points the world of nature provides inspiration and solace.

The Byronic Hero

Romanticism set a trend for some literary stereotypes. Byron’s Childe Harold (1812-1818) described the wanderings of a young man, disillusioned with his empty way of life. The melancholy, dark, brooding, rebellious ‘Byronic hero’, a solitary wanderer, seemed to represent a generation, and the image lingered. The figure became a kind of role model for youngsters: men regarded him as ‘cool’ and women found him enticing! Byron died young, in 1824, after contracting a fever. This added to the ‘appeal’. Subsequently a number of complex and intriguing heroes appeared in novels: for example, Heathcliff in Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights and Edward Rochester in Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre (both published in 1847).

Contraries

Romanticism offered a new way of looking at the world, prioritizing imagination above reason. There was, however, a tension at times in the writings, as the poets tried to face up to life’s seeming contradictions. Blake published Songs of Innocence and of Experience, Shewing the Two Contrary States of the Human Soul (1794). Here we find two different perspectives on religion in ‘The Lamb’ and ‘The Tyger’. The simple vocabulary and form of ‘The Lamb’ suggest that God is the beneficent, loving Good Shepherd. In stark contrast, the creator depicted in ‘The Tyger’ is a powerful blacksmith figure. The speaker is stunned by the exotic, frightening animal, posing the rhetorical question: ‘Did he who made the Lamb make thee?’ In The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1790-1793) Blake asserted: ‘Without contraries is no progression’ (stanza 8).

Wordsworth’s ‘Tintern Abbey’ (1798) juxtaposed moments of celebration and optimism with lamentation and regret. Keats thought in terms of an opposition between the imagination and the intellect. In a letter to his brothers, in December 1817, he explained what he meant by the term ‘Negative Capability’: ‘that is when a man is capable of being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason’ (22 December). Keats suggested that it is impossible for us to find answers to the eternal questions we all have about human existence. Instead, our feelings and imaginations enable us to recognize Beauty, and it is Beauty that helps us through life’s bleak moments. Life involves a delicate balance between times of pleasure and pain. The individual has to learn to accept both aspects: ‘“Beauty is truth, truth beauty,” – that is all/Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know’ (‘Ode on a Grecian Urn’ [1819]).

The premature deaths of Byron, Shelley and Keats contributed to their mystique. As time passed they attained iconic status, inspiring others to make their voices heard. The Romantic poets continue to exert a powerful influence on popular culture. Generations have been inspired by their promotion of self-expression, emotional intensity, personal freedom and social concern.

Romantic Rhetoric

The Romantics influenced rhetoric in many ways.

- The focus on using the language of the common people led to a use of Analogy instead of enthymemes and syllogisms.

- The focus on Nature led to the belief that composition should grow instead of being constructed. It should be “organic.”

- Creation of Pulpit/Sermon Rhetoric. This style of speech focused on expressiveness, certain types of organization, appeals to the emotions, ethics, and aesthetics. There should be a dual focus on speaking from the heart and rhetorical considerations. Sermons should be both literary and rhetorical so as to appeal to the common man.

- The value of personal writing, like diaries and letters, and extemporaneous speech was elevated.

- The focus on the individual led to a reliance on pathetic appeals to drive home messages. The emphasis was on the sublime, especially nature and the unpredictable acts of God. `The goal was for the audience to identify with a poem or story and participate through the imagination.

- There was a focus on the past, the surprising, and nature to find harmony with self and God.

- Romantic rhetoric relied upon an appeal to unity in the audience; they believed that the audience must be a willing participant in the communication act and try to identify with the speaker.

Key Figures:

Giambattista Vico (1668-1744)

Giambattista Vico or Giovanni Battista Vico was an Italian philosopher, historian, and jurist. Vico presented his philosophical methodology and theory of knowledge in sharp contrast to those of Descartes. While Descartes attempted to establish a new ground of philosophy based on the presuppositions that geometry is the model of knowledge, and that the primary criterion of truth is certainty, and this “certain” truth can be gained by the exercise of reason, Vico presented the effectiveness of “probable” truth, adaptation of “prudence,” and values of rhetoric particularly for human and social sciences. From Vico’s perspective, Descartes’ view of knowledge and adherence to geometry was one-sided, and limited the sphere of knowledge. In contrast to Descartes’ quest for simplicity and clarity in knowledge, Vico pursued a philosophical methodology to disclose richness and diversity in knowledge. His Scienza Nuova was the culmination of his efforts to create a comprehensive philosophy through a historical analysis of civil society.

Vico’s version of rhetoric is the result of both his humanist and pedagogic concerns. In De Studiorum Ratione, presented at the commencement ceremonies of 1708, Vico argued that whoever “intends a career in public life, whether in the courts, the senate, or the pulpit” should be taught to “master the art of topics and defend both sides of a controversy, be it on nature, man, or politics, in a freer and brighter style of expression, so he can learn to draw on those arguments which are most probable and have the greatest degree of verisimilitude.” As Royal Professor of Latin Eloquence, it was Vico’s task to prepare students for higher studies in law and jurisprudence. His lessons thus dealt with the formal aspects of the rhetorical canon, including arrangement and delivery. Yet as the above oration also makes clear, Vico chose to emphasize the Aristotelian connection of rhetoric with dialectic or logic. In his lectures and throughout the body of his work, Vico’s rhetoric begins from argumentation. Probability and circumstance are thus central, and invention – the appeal to topics or loci – supersedes axioms derived through pure reasoning.

Vico’s recovery of ancient wisdom, his emphasis on the importance of civic life, and his professional obligations compelled him to address the privileging of reason in what he called the “geometrical method” of Descartes and the Port-Royal logicians.

Vico had a holistic view of mind and body that posited that imagination was necessary to make sense of the world. He believed that a study of myths and fables would help develop the imagination. Like most Romantics, he believed that current words were imitations of nature. Adopting Aristotle’s enthymemes, he believed that rhetoric is the foundation of society.

Vico’s Work

n 1720, Vico began work on the Scienza Nuova—his self-proclaimed masterpiece—as part of a treatise on universal law. Although a full volume was originally to be sponsored by Cardinal Corsini (the future Pope Clement XII), Vico was forced to finance the publication himself after the Cardinal pleaded financial difficulty and withdrew his patronage. The first edition of the New Science appeared in 1725, and a second, reworked version was published in 1730; neither was well received during Vico’s lifetime.

David Hume (1711-1776)

David Hume was an 18th-century Scottish philosopher, known for his empiricism and skepticism. He was a major figure in the Scottish Enlightenment.

Hume begins his essay Of the Standard of Taste by discussing whether it is possible to propose a universal system of ethics. He proposes that the mere naming of specific moral attitudes gives the impression that these are desirable, but study of poetry soon makes it clear that different poets, and different cultures, praise different ethical values. He proposes that there is no merit in a notion of a universal morality, and that there can be no general standard of taste. This derives from the idea that there are two ways to consider an object, through judgement and through sentiment. Because judgements make reference to real facts they can be true or false. But sentiment, the way an individual feels about an object, cannot conform – ‘all sentiment is right’ as it derives from the individual’s perception and experience, culture, education, etc. “Beauty … exists merely in the mind which contemplates [things]; and each mind perceives a different beauty.”

What Hume is proposing is that anything can provoke a wide range of reactions of taste; an object has no inherent quality of taste. “Beauty is no quality in things themselves; it exists merely in the mind which contemplates them; and each mind perceives a different beauty.”

Hume defined high and low rhetoric depending on the purpose. Low rhetoric is manipulative, while high rhetoric is polite and accurate.

Hume’s Work

Edmund Burke (1729-1797)

Burke was an Irish statesman and philosopher. Born in Dublin, Burke served as a member of parliament (MP) between 1766 and 1794 in the House of Commons of Great Britain with the Whig Party after moving to London in 1750.

Burke was a proponent of underpinning virtues with manners in society and of the importance of religious institutions for the moral stability and good of the state. These views were expressed in his A Vindication of Natural Society. He criticized the actions of the British government towards the American colonies, including its taxation policies. Burke also supported the rights of the colonists to resist metropolitan authority, although he opposed the attempt to achieve independence. He is remembered for his support for Catholic emancipation, the impeachment of Warren Hastings from the East India Company, and his staunch opposition to the French Revolution.

In his Reflections on the Revolution in France, Burke asserted that the revolution was destroying the fabric of good society and traditional institutions of state and society and condemned the persecution of the Catholic Church that resulted from it. This led to his becoming the leading figure within the conservative faction of the Whig Party which he dubbed the Old Whigs as opposed to the pro-French Revolution New Whigs led by Charles James Fox.

In the 19th century, Burke was praised by both conservatives and liberals. In the 20th century, he became widely regarded as the philosophical founder of modern conservatism.

Thomas Sheridan (1719-1788)

Sheridan was an Irish author and actor. The godson of Jonathan Swift, he wrote at least eleven book son pronunciation, including the Dictionary of the English Language. His goal was to make English the international language. He believed that a person’s accent affected their credibility.

Gilbert Austin (1753-1837)

Austin was an Irish minister who established a private school and wrote Chironomia, or a Treatise on Rhetorical Delivery, which focused on using hand gestures while speaking.

Austin observed that British orators were skilled in the first four divisions of rhetoric: inventio, dispositio, elocutio, and memoria. However, the fifth division, pronuntiatio or delivery, was all but ignored. Rather than study the art of delivery, orators trusted to the inspiration of the moment to guide their voices and gestures.

Chironomia is a treatise on the importance of good delivery. Good delivery, Austin notes, can “conceal in some degree the blemishes of the composition, or the matter delivered, and…add lustre to its beauties” (187). In the first part of the book, Austin traces the study of the art of delivery from the classical world to the 18th century. The second part of the book is devoted to a description of the notation system Austin designed to teach students of rhetoric the management of gesture and voice. The system of notation is accompanied by a series of illustrations depicting positions of the feet, body and hands.

Throughout Chironomia, Austin instructs speakers to avoid the appearance of vulgarity or rusticity. Austin first developed the system of notation described in Chironomia at his school for privileged young men. Austin’s goal was to prepare his students for a life in the church or politics by training them to become better orators. Although Austin’s system was eventually dismissed as too rigidly prescriptive, Chironomia was a highly influential book during the 19th century.

Austin’s Work

Hugh Blair (1718-1800)

Blair was a Scottish minister and professor who believed that speech should be sincere and that speakers should clearly understand the rhetorical situation. Fond of Quintilian, he believed that “True eloquence is the art of placing truth in the most advantageous light for conviction and persuasion.”

Hugh Blair on Rhetoric and the Belles Lettres

Thomas De Quincey (1785-1859)

British author and opium addict.

Thomas De Quincey’s Confessions of an English Opium-Eater was first published in 1821 in the London Magazine. It professes to tear away the ‘decent drapery’ of convention and present the reader with ‘the record of a remarkable period’ in the author’s life, beginning when he ran away from school at the age of 17 and spent several months as a vagrant. It is the sections that describe his opium addiction, however, that have become the most famous. De Quincey began to take the drug as a student at Oxford, to relieve a severe bout of toothache, and remained dependent on it for the rest of his life. He describes, in vivid detail, the visions and dreams he experiences, conjuring up a world of contrasts that was both a ‘paradise’ and a place of ‘incubus and nightmare’.

De Quincey wrote his Confessions while unknown and in debt, but the work caused such a sensation that his literary fame was secured, and his account of his addiction has become a central Romantic text.

De Quincey’s Work

The Literature of Knowledge and Power

Romanticism vs the Enlightenment

Here’s a short video discussing how Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein illustrates the tension between the ideas of Romanticism and the Englightenment:

This table shows a simplistic view of the differences between the Enlightenment and Romanticism:

| Enlightenment | Romanticism |

| Reason | Passion/Emotion |

| Human nature | Nature |

| Man over nature | Nature over man |

| Forward looking | Backward looking |

| Ignore the middle ages | Look to the middle ages |

Looking at work of Descartes and Vico side by side can also give us an interesting look at the contrast between the two styles.

Descartes vs Vico

Additional Resources:

- American Romanticism from the Stevenson Library Digital Collections

- An overview of Romantic Rhetoric/Aesthetics from Stanford

- What was Romanticism?

- Discussion Descartes vs Vico

Attributions

- References from the following texts:

- Smith, Craig R. Rhetoric and Human Consciousness, 5th Edition. Waveland Press, 2017.

- Percy Bysshe Shelley, Shelley’s poetry and prose: authoritative texts, criticisms, ed. by Donald H. Reiman and Sharon B. Powers (New York; London: Norton, c.1977), p.485.

- Content adapted from “The Enlightenment” by Matthew White licensed CC BY NC.

- Content adapted from “Romanticism” by Stephanie Forward licensed CC BY NC.

- Content adapted from “The Industrial Revolution” by Matthew White licensed CC BY NC.

- Content adapted from “Four Dissertations” licensed under CC BY.

- Descartes licensed CC SA.

- Campbell licensed CC SA.

- “Vico” licensed CC BY.

- “Burke” licensed CC BY.

- “Austin” licensed CC BY.

- “Confessions of an Opium Eater” licensed CC BY.