3

Bonni Stachowiak

“Every transition begins with an ending. We have to let go of the old thing before we can pick up the new one—not just outwardly, but inwardly, where we keep our connections to people and places that act as definitions of who we are.” – William Bridges

I remember when my Instapot first arrived at our house. The box was heavy and I wasn’t sure what to expect. I had read a little bit about the device and also watched some videos online. I was ready to learn something new. But I wound up having some unlearning to do, first. And I would have to begin at the end, instead of the beginning.

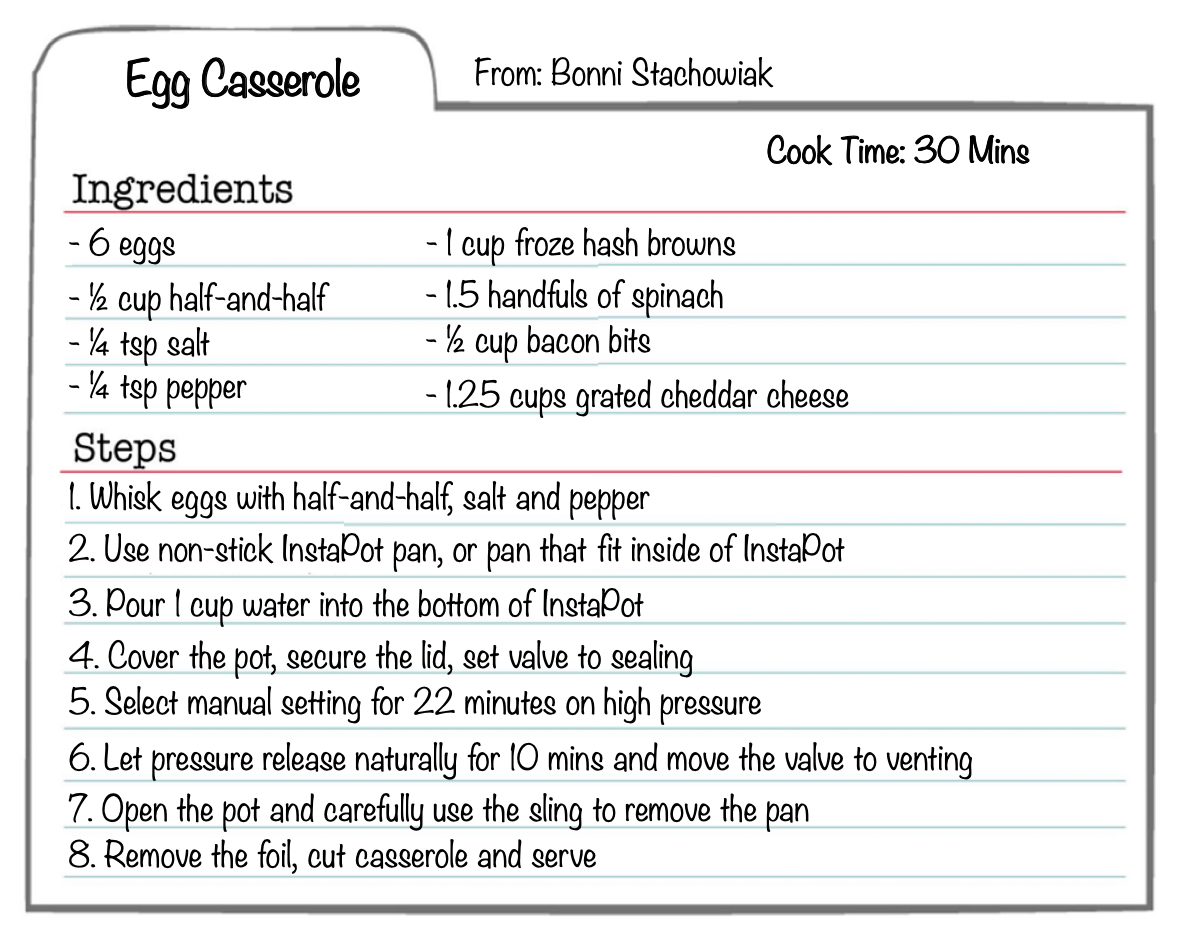

The ending involved leaving our slow cooker behind (though the Instapot would allow us to return to that method of cooking in the future, should we want to, unlike most of the change we go through in life). I tried out cooking an egg casserole, which looked delicious.

It took a really long time to cook. One thing I had not realized was how long it takes to build up enough pressure to actually consider that you have started the cooking process. If the recipe tells you to cook something for five minutes, it is going to take longer than that just to get the thing ready – and full of the needed pressure.

Finally, the meal was ready. It was delicious, but my goodness was the cleanup ever challenging. I wound up buying a non-stick pan accessory to go with the Instapot, as I never wanted to spend that much time on the process of getting it clean, again.

Change can be hard. But as leaders, we can help people navigate through it and come out the other side with a greater sense of vision and purpose.

There are the changes we welcome and transitions we would rather not make. What would sometimes be seen as solely good developments in our lives can have us experience unexpected twists that make us question what we have gotten ourselves into. The times in our lives when we are navigating tremendous grief can cause us to have difficulty envisioning any other way of living besides in our current state of writhing…

Such is the nature of transformation.

In his book, Transitions: Making Sense of Life’s Changes, William Bridges (2008) illustrates how people often say that we resist change, but what we actually resist is transition. Change involves a difference in the situation, but transition “is the process of letting go of the way things used to be and then taking hold of the way they subsequently become” (p. 2)

We expect that when we embark on something new that we will launch at the starting point. Instead, we begin with the endings. We must release how things used to be, in order to discover a new normal. This happens with the good stuff and the bad – and everything in between.

Bridges (2008) explains this counter-intuitive chronological order of change:

“Before you can begin something new, you have to end what used to be. Before you can learn a new way of doing things, you have to unlearn the old way… So beginnings depend on endings. The problem is, people don’t like endings” (p. 23).

As we leave the endings behind, we don’t immediately move to the beginnig we were hoping for in the first place. Instead, we enter a middle space. “In between the letting go and the taking hold again, there is a chaotic but potentially creative ‘neutral zone’ when things aren’t the old way, but aren’t really a new way yet either,” reveals Bridges (2017, p. 2).

I have been in the ‘neutral zone’ many times in my life. Now, instead of trying to fight it as much, I often think to myself, “Hello, old friend.” This season often brings with it a heightened level of creativity, if we are willing to sort through all the ambiguity it brings.

My role at our institution was elevated to Dean about six months ago. It has felt a lot like driving a stick shift car at points. Some aspects of the position feel comfortable and I have confidence in attempting to influence change. However, other aspects of the job are more of a challenge. Others have gone through their own times of transition, prior to my being asked to provide leadership in my capacity. I find myself wanting to listen and recognize the tremendous losses they have experienced. In other cases, I feel a sense of urgency for us to hurry up and get to the next part where everyone has healed from the difficulties of the past.

Change is rarely something we can hurry along.

Bridges (2009) describes the challenge of being in transition in our modern age, without the rituals that were performed in generations past. Some of these traditions had to do with marking the time of becoming an adult, while others were used to provide space for those who were grieving.

Cultures embraced the idea that people would need to go out into the wilderness and either test their skills of survival or give them time to reflect on the changes they were experiencing. This was a time of isolation to represent the time in-between being a child and becoming an adult. It also might be a season of being set apart in mourning the loss of a loved one.

Today, we are expected to get back to normal as soon as possible immediately following significant shifts in our lives. We’re expected to make these transitions without even experiencing deep pain – or at least to do everyone a favor and avoid expressing our hurt.

Anne Lammot illustrates the ways in which we are asked to keep our grief to ourselves in her book:

Operating Instructions: A Journal of My Son’s First Year

“I had a session over the phone with my therapist today. I have these secret pangs of shame about being single, like I wasn’t good enough to get a husband. Rita reminded me of something I’d told her once, about the five rules of the world as arrived at by this Catholic priest named Tom Weston.

The first rule, he says, is that you must not have anything wrong with you or anything different.

The second one is that if you do have something wrong with you, you must get over it as soon as possible.

The third rule is that if you can’t get over it, you must pretend that you have.

The fourth rule is that if you can’t even pretend that you have, you shouldn’t show up. You should stay home, because it’s hard for everyone else to have you around.

And the fifth rule is that if you are going to insist on showing up, you should at least have the decency to feel ashamed.

So Rita and I decided that the most subversive, revolutionary thing I could do was to show up for my life and not be ashamed” (Lamott, p. 100).

Showing up is essential to being an effective leader. Yet, there’s every excuse to distance ourselves in the hopes that perhaps people won’t notice that not everything is going according to plan.

The neutral zone cannot be ignored.

We tend to believe that “the neutral zone is not an important part of the transition process – it is only a temporary state of loss to be endured” (Bridges, 2009, p. 112). But, Bridges shows us that there is another way to experience transition, one that helps us to tap into our creativity and to develop a new reality for ourselves.

Bridges recommends a number of techniques to assist in the process, including having a quiet time regularly, keeping a journal during the neutral zone, writing an autobiography, learning what it is you really want in life, contemplating what would be missing from your life if it ended immediately, and creating and going on your own version of a “passage journey.”

As I learn to move people through the neutral zone in my new role, it has been helpful for me to write down the kind of leader I want to be. After gathering everyone’s talents from the CliftonStrengths assessment, I discovered that I am the only person out of about 20 who possesses the futuristic strength. They state on their website that people with this talent are:

“…inspired by the future and what could be. They energize others with their visions of the future.”

This process of reflecting and assessing the collective strengths of the teams that I now lead was helpful in determining where they need me most. Additionally, I was able to discern where we might be able to leverage the strengths of team members who may not be as aligned to be able to make their greatest contributions currently.

The final stage of Bridges’ (2009) model is the new beginning. As leaders, we can expect that as our teams enter this phase, individuals will be motivated and open to new ways of seeing the future. Revived energy is present as people discover the unique roles they play in achieving the group’s vision.

I have enjoyed seeing people in the various teams begin to find new ways to contribute to our university – and ultimately our students. There are new spaces to study and collaborate. For those struggling with finances, there is a new place they can come to receive food, meet others encountering similar difficulties, and discover community resources to support them during this time. We have launched new programs for our faculty to share their research and to learn more about culturally-responsive teaching. We still experience struggles – but we recognize more how to work together to overcome them. We also all try to keep our collective sense of humor, which really helps to keep things in perspective.

Recipe for Leadership

Recognize that transitions begin with endings. Navigate the neutral zone by capitalizing on the abundance of ideas and by finding some structure to hold you over until you get to a new normal. Spend time marking the season of change by journaling, reflecting, and learning more about yourself and your team. Emerge into the new beginning, taking advantage of a renewed sense of vision and purpose.

A Recipe for Your InstaPot