2

- To define different theoretical standpoints

- To identify the major frames of reference in employment relations

- To examine the content of frames of reference and their application

- To show that the multidisciplinary foundation of employment relations has created theoretical tensions and debates

- To highlight new theoretical understandings and their employment relations application

Introduction

Employment relations issues are discussed across different academic disciplines and different theoretical approaches have been developed over the years. As in other disciplines, there are different ideas about how certain issues can be explained. Different ideas and opinions are not unique to academia but can be found throughout different parts of society. Most of us have an opinion, one way or the other, about how we work, with whom we want work and how we view those representing our interests and the interests of the other parties. Often our opinion is shaped by where we stand in the organisation’s hierarchy. Management and worker ideologies and attitudes are important because they determine the way we behave. For example, a dispute over pay will normally be seen in totally different ways by an employer and by workers. The employer may view a pay rise for workers in terms of less profit for the firm or reducing investment plans while the workers may see the pay rise as necessary for them to pay their bills and as a rightful reward for working hard.

These different ways of seeing employment relations are called frames of reference or ideologies and are useful tools to help us understand both what is occurring in the employment relationship and also in respect of wider employment relations issues. As there are different and competing frames of reference and ideologies, no single approach satisfies everyone. Some view the workplace as a microcosm of our society with continual tension between employers and employees. Others view organisations as integrated and harmonious collections of people working towards a common goal. Still others see employment relations as a system containing a set of beliefs governed by rules and procedures. These frames of reference have been developed to help us understand events and behaviours that occur in employment relations.

In this chapter, we shall look at the four main theoretical approaches, keeping in mind the strengths and weaknesses of each of them. The chapter begins with a brief presentation of the systems approach. This is followed by an overview of the conflict frames of reference with an emphasis on the traditional three versions: pluralism, unitarism, radical pluralism. The second part of the chapter highlights the multidisciplinary foundation of employment relations and show how new theories and research angles have influenced our current understanding. We show how such theories can be applied to particular problems or issues and exemplify how this can broaden our understanding of employment relations.

Systems approach

One influential work is John Dunlop’s 1958 book entitled Industrial Relations Systems (see also the updated version, Dunlop, 1993). Dunlop argues that it is useful to treat employment relations as a system in order to analyse and interpret the widest possible range of employment practices. Employment relations are seen as a distinctive system although one that partially overlaps and interacts with social, economic and political systems. The focus in the systems approach is to establish and maintain stability and order in a changing environment and it emphasises the interdependencies and interactions between organisations and their environment. In the context of employment relations, the core feature of this system is, according to Dunlop, a system of rules.

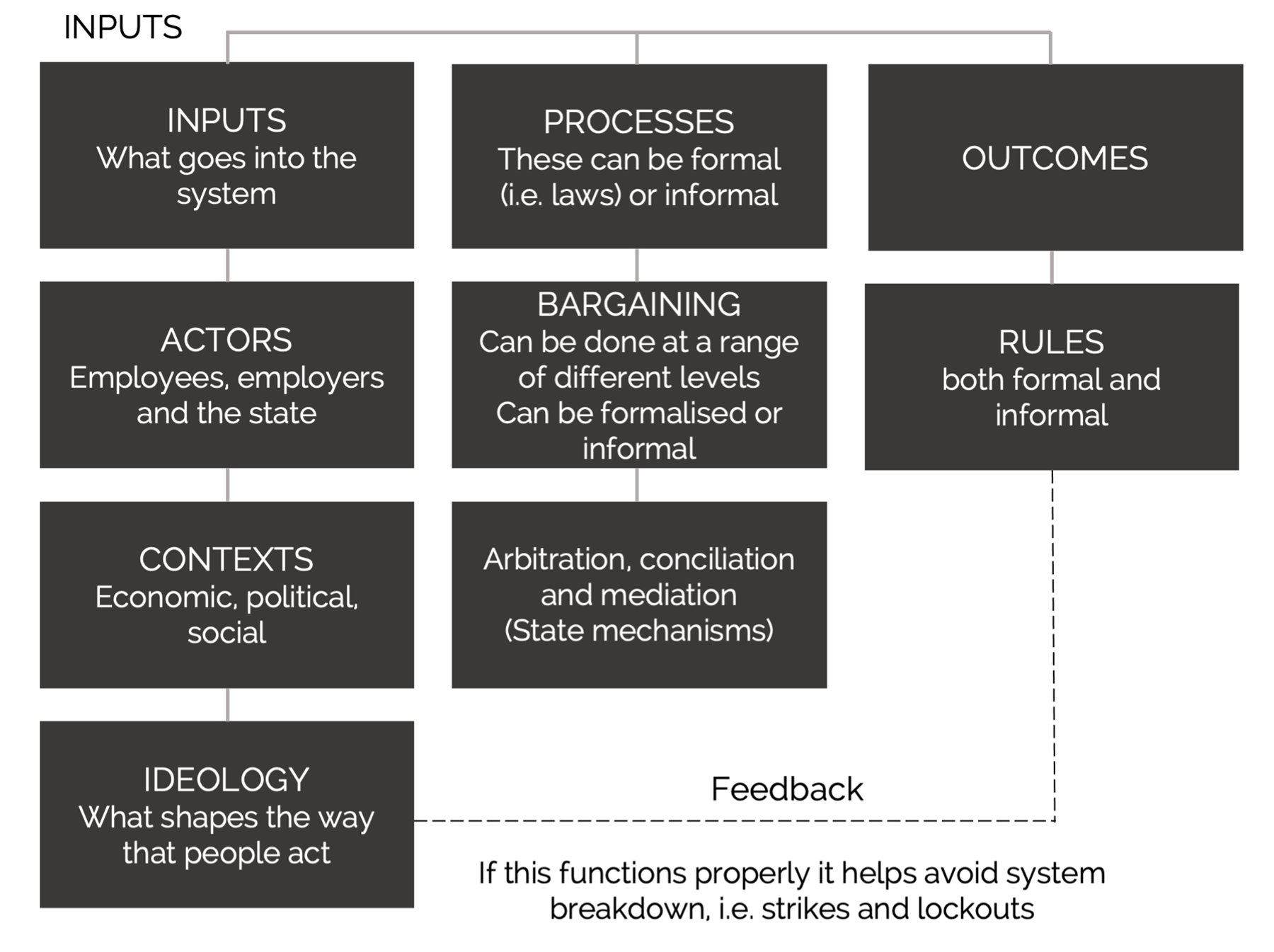

Figure 2.1 shows a system model of employment relations, with inputs that through different processes result in outcomes. The inputs include three parts, namely actors, context and ideology. The actors refer to a hierarchy of managers and their representatives as well as a hierarchy of non-managerial employees and their representatives. As these two actors often have competing interests the role of the state, as the third actor, is to balance the power between employers and employees. Context refers to the economic, political, and social conditions and how, for example, a political election and the economy impacts upon employment opportunities and working conditions. Ideology in this context refers to certain ideas and beliefs regarding the interaction between aforementioned actors.

The processes in the systems approach refers to different activities that are often discussed and analysed in the field of employment relations. These processes refer to, for example, bargaining, negotiation, conciliation, arbitration and other examples of state intervention. Finally, inputs and processes result in outcomes of the system. The outcomes are, according to Dunlop, two types of rules, namely substantive rules – those that set out the conditions under which people are to be employed, found in for example legislation as well as employment agreements – and procedural rules – that govern how the substantive rules are to be made and interpreted (that includes, for example, processes for negotiation and conflict resolution).

Substantive rules are concerned with what is negotiated and set out the conditions under which people are to be employed.

Examples of substantive rules are agreements about wages, holiday pay, and leave entitlements and can be found in legislation.

Substantive rules can also be the result of bargaining and negotiation between employers and employees and can be found in an individual or collective employment agreement.

Finally, substantive rules can also be less formal rules. For example, work practices and expectations (for example weekly expected outputs from employees) as well as management rules and directives.

Procedural rules are concerned with how substantive rules are to be made and interpreted. Examples include how collective bargaining is carried out, as well as how an employee can raise a personal grievance.

Dunlop’s systems approach has been extensively critiqued, in particular for placing too much focus on description of what is existing rather than explaining why there are certain tensions between different actors. Conflict is taken as a natural part of employment relations and the systems approach does little to attempt to explain why there is conflict. Another criticism is that it does not adequately discuss the role of power in the employment relationship. This is problematic, as the power struggle between employer and employee interests can be seen as a fundamental part of the employment relationship.

Although Dunlop’s system approach has been criticized, it has had an immense influence on the understanding of employment relations. It has, for example, influenced our definition of employment relations (see Chapter one) where concepts such as rules, processes, contexts and key parties are used. Further, the systems approach is often used in comparative employment relations, where this framework enables comparison between different national employment relations systems. For example, processes of conflict resolution processes or collective bargaining coverage are issues that can be compared using a systems approach.

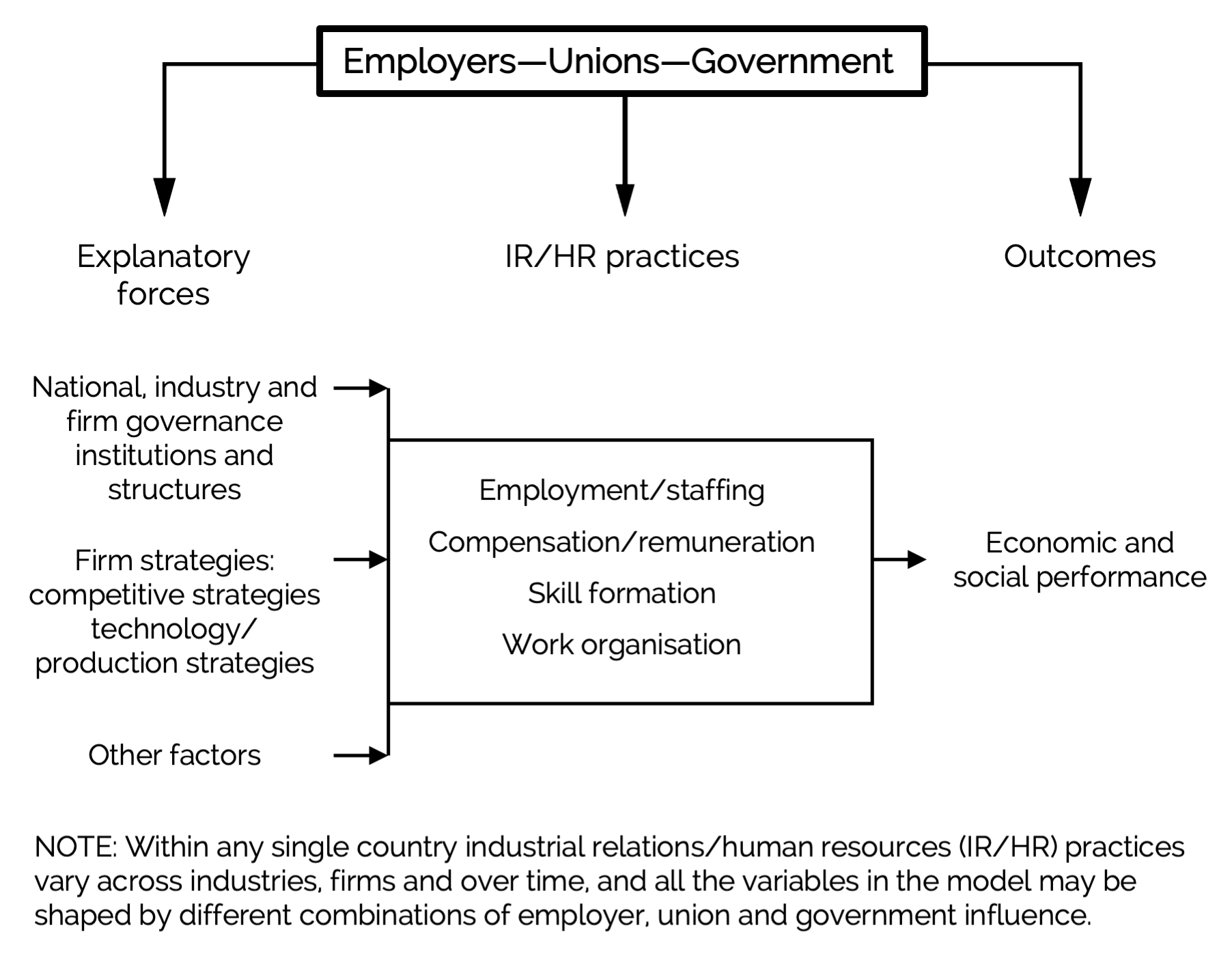

While the thinking and elements of Dunlop’s system model can be detected in many discussions of ‘national employment relations systems’ there have also been distinct attempts to employ insights in other theoretical developments. In light of more pro-active employer strategies and interventions, several American researchers developed new bargaining approaches and understandings of employment relations processes. The Strategic Choice Model, presented in Figure 2.2, is clearly inspired by Dunlop’s system model but it is also influenced by the rise of employer power and human resource management practices.

As can be seen from Figure 2.2, the Strategic Choice Model presents a model, just as Dunlop’s system model, that can be applied to a national employment relations system. There is also a focus on actors, contexts and bargaining which provide the general settings for employment relations. This allows the model to be applied to different countries. However, there are also major differences as the Strategic Choice Model incorporates a distinct workplace or firm perspective and allows for a much stronger, pro-active role for employers and managers. This is highlighted in the model when it focuses on four different types of employment relations processes that clearly have some affinity with traditional human resource management areas.

The strategic choice model had two further important implications. First, it was associated with a number of comparative industry studies which reviewed key people management trends across a number of OECD countries (see Gittell & Bamber, 2010; Kochan, Lansbury & MacDuffie, 1997; Regini, Kitay & Baethge, 1999). These studies highlighted how, within specific industries, general trends spread across many OECD countries while, at the same time, there are distinct national differences in terms of extent, combination and speed of such industry changes. Second, Katz and Darbishire (2000) have suggested that the patterns of changes were resulting in ‘converging divergences’ across and within countries. While the spread of technology, managerial strategies and internationalization were amongst some of the influences which led to industry convergence across countries – for example, similar approaches in the car manufacturing industry – there were also growing divergences within countries. These divergences were driven by different industry employment relations approaches where, for example, the financial sector would have different employment standards and approaches to those existing in the fast-food sector.

Source: Adapted from an original in Kochan, Locke & Piore (1992)

As discussed above, Dunlop’s system model highlights the importance of rule-making. Recent studies have been taken this argument further in analysing legislative frameworks and how rule-making “gives priority to the processes of rule-making embodied in and promoted by national labour laws.” (Bray & Stewart, 2013, p. 21). This allows an evaluation of the legal hierarchy and regulatory priority of rule-making processes associated with different legislative frameworks, including both the rule-making processes and the application of rule-making evaluations (see Bray & Stewart, 2013; Rasmussen, Bray & Stewart, 2019). In summary, the Dunlop model views employment relations as a distinctive system which is useful in order to analyse and interpret the widest possible range of employment practices.

Conflict frames of reference approach

It is argued that the systems approach is inadequate and that there is a need to dig beneath the surface elements of employment relations, such as collective bargaining, management decision making, legislation, representation and workplace custom and practice. The systems approach has a tendency to ignore the tension that exists in the relationship between the employer and the employee or to treat it as a combination of individual responses and actions. Conflict theorists, on the other hand, are united by their recognition that conflict exists in the workplace. However, their views of the ways in which conflict is manifested, managed and resolved, differ (see Figure 1.3). The following sections outlines three main frames of reference: unitarism, pluralism, radical pluralism.

Unitarism

The unitary frame of reference does not recognise major divergent interests amongst individuals in the workplace. Those who advocate the unitary frame of reference assume that each employee identifies with the aims of the company and with its methods of operation. For this reason, there should be no divisions or conflict of interest between managers and employees because it is in everyone’s interest to have efficient production, high profits and good pay.

The unitarist frame of reference has a couple of implications. In the first place, the source of authority lies with management. This view legitimises management prerogative within the workplace and, therefore, management as the sole decision maker. Good employment relations equate with good business and therefore authority can be left in the hands of management. Employees, on the other hand, are motivated by the need to keep their jobs and are not expected to challenge managerial decisions or their employer’s right to manage. Employers also believe that it is unacceptable that there should be a third party intervening in the direct employer-employee relationship. Therefore, trade unions are viewed as an unwanted intrusion, creating unnecessary conflict in an otherwise harmonious working environment (see Table 3.2 in Bray et al., 2018, p. 54).

Since the 1980s unitarist ideology has become more refined and is often referred to as ‘neo-unitarism’ where it has found its way into many New Zealand organisations both publicly and privately owned. Amongst most OECD countries, there has been a trend of weaker unions and less collective bargaining and the resultant employer and managerial confidence in their workplace governance (Foster et al., 2013). Neo-unitarism’s main aim is to integrate employees, as individuals, into their organisations where they will become loyal, committed to quality production, customer needs, and job flexibility. Managers, who subscribe to this frame of reference, seek to create a sense of common purpose and corporate culture, set targets for their employees, and invest in training and management development. Techniques to facilitate commitment, quality and flexibility include performance-related pay, profit sharing and employee involvement (Stone et al., 2018). A more sinister version can be found in the so-called ‘egoist’ version of unitarism, developed by John Budd and his colleagues, where a market-orientated, individualised approach can be aligned with unbalanced employment relationships (see below).

Interestingly, the rise of neo-unitarism in New Zealand has coincided with an increase in the number of human resource managers, many of whom advocate the neo-unitarist view, according to Haworth (1990). It is also suggested that the Employment Contracts Act not only epitomised the neo-unitarist ideology but also accelerated its embeddedness in workplace employment practices (see Chapter 3).

Pluralism

In the 1960s, there was a distinct reaction against the systems approach. Based on research done at Oxford University, employment relations theorists, such as Hugh Clegg, Alan Fox and Allan Flanders, argued that employment relations are much more than a single system held together by one ideology and individuals and groups pursuing their own goals, yet each is dependent upon the others for mutual survival. The collective means by which individuals pursue their goals is not only natural, but also valid. Conflict is accepted as both inevitable and legitimate within any organisation and is tempered and controlled through structures and procedures (see Table 3.3 in Bray et al., 2018, p. 60).

The potential conflict that exists between employers and employees can be eased by recognising and involving trade unions. Pluralists argue that greater stability can be achieved by working with trade unions than by outlawing them. Although trade unions are viewed as the legitimate representatives of employees with the right to challenge management, there is still the notion of managerial prerogative. That is, that employers have the legitimate right to manage and to require loyalty from their staff, but must include the other interest groups in the decision-making process.

While pluralists would agree with the radical pluralists and Marxists that society is neither static nor harmonious, they would argue, however, that it is possible to achieve relative stability and accord through negotiation, concession and compromise between the different interest groups. Therefore, organisations have to accommodate different and divergent groups in order to accommodate change. In addition, there is a rough equality of power between the different groups which is adjusted by both formal rules such as legislation and informal work or union rules. Power should be diffused among the main bargaining groups so that no one party dominates the other. Rules and laws should restrain the abuse of power and should enable all parties to accomplish some gains. Also, the role of the government should be to protect the weak and restrain the power of the stronger interest groups.

However, the pluralist approach concentrates on controlling and resolving conflict, rather than on understanding why it is generated in the first place (Bray et al., 2018, p. 61). That is, pluralism offers no comprehensive explanation for industrial conflict, beyond acknowledging that different interests prevail in the workplace. Although pluralism recognises that there is an imbalance of power at the corporate and workplace level, it assumes that there is an approximate balance of power at the national level, with the government acting as neutral referee (see Chapter 10 in Rasmussen, 2009). As a result, pluralists have a tendency to focus on how conflict can be managed while ignoring the nature or basis of conflict.

Radical Pluralism and Marxism

Based on the political economy work of Karl Marx, radical pluralism and Marxism offer a different perspective on our understanding of society and employment relations (Bray et al., 2018: 66-70). Radical pluralists and Marxists treat society as fundamentally polarised into two classes: the employers (or capital) and employees (or labour).

This class polarisation is based on the mutual incompatibility of their interests. Radical pluralists and Marxists maintain that the interests of the employers are not legitimate but exploitative. Since employers own the means of production (that is facilities, technology, tools, and machinery) and have power over employees (also referred to as managerial prerogative), who can only sell their labour (time and effort) for wages, there is an inherent inequity in the distribution of rewards in favour of employers (that is employers and owners of a company receive the surplus). Also, any government in a capitalist society will inevitably protect the interests of the powerful and maintain the structural features of society that are crucial to the employers’ existence, for example through tax cuts and incentives to invest. The government will control employment conflict through adjudication, mediation and the courts in order to advance employers’ interests while at the same time playing a decisive role in defeating strikes through the use of the law.

Radical pluralists and Marxists argue that conflict is inherent in employment relations for two reasons. Firstly, our society is class-based and ownership acts as a source of power and control. This gives employers, who own the means of production, the right to employ workers and direct how they shall work (Frege, Kelly & McGovern, 2011). The resulting conflict between employers and employees has become institutionalised, with bargaining agents and a set of parameters laid down by the state and judiciary. Also, the vulnerability of employees as individuals invariably leads them to form trade unions in order to protect their own interests. Trade unions, while they cannot resolve conflict, are viewed as the inevitable consequence of the employers’ exploitation of employees (Bray et al., 2018). Secondly, since the workplace mirrors our society, individuals will have differing values, interests and objectives. Therefore, employers and employees will have different attitudes and beliefs and, in turn, these will create tension and ultimately conflict between the two camps.

However, radical pluralist and Marxist theories are criticised because they are based on ideas developed in the 19th century and as a result are seen to have little relevance for the 21st century. Critics maintain that the growth of middle management and professionals does not exactly fit in with the simplistic view that the working environment is divided into two groups – employers versus employees (for new insights on management theory, see Cummings et al., 2017). It is argued that because radical pluralist and Marxist analysis is predominantly directed at identifying the source of conflict, it has difficulty in recognising other potential outcomes of employment relations. The pluralist and Marxist view is that changes in the structures and institutions will create changes in the relationship between the employer and employee. However, others argue that this will not automatically occur. That is, there has to be a succession of changes in society at large before changes in the fundamental aspects of employment relations are likely to take place.

The application of frames of reference

New Zealand’s employment legislation from the early Industrial Conciliation and Arbitration Act 1894 to the Labour Relations Act 1987 aimed to control and institutionalise conflict (see Chapter 3). The dominant employment relations orthodoxy during that period, and particularly in the 1960s and 1970s, was pluralism with its consensus politics, tripartite relations amongst government, employers and trade unions, and collectivism dominating employment relations (Williamson, 2016). At the corporate level, employment relations were controlled by industrial relations managers who often started as union delegates and typically worked their way up within the organisation structure.

| Theory | Management | Workers | Unions | Conflict | The state |

| Unitarism | Legitimate source of authority | Resources to be applied to production process | Outside intrusion into relationship between firm and employee | Unnecessary and incompatible with the aims of the organisation | Should provide a minimal framework but has no special interests in the employment relationship |

| Pluralism | Co-ordinator of a coalition of interests | Partners in production | Legitimate representative of workers’ interests | Inevitable – can be resolved positively by an institutional framework that encourages consensus | Acts as the referee by providing institutions to resolve conflict; represents ‘the public good’ |

| Radical pluralism | Exploiter | Exploited | Only voice for exploited | Inevitable – will only ever end with the overthrow of capitalism | Coercive arm of capitalism |

Source: Rasmussen & Lamm, 2002, p. 17

During the late 1980s and through the 1990s, the pluralist frame of reference shifted more towards a unitarist approach with its emphasis on management prerogative, individualism, freedom of association, workplace bargaining, market-led wage determination and market economy (see Chapter 3). With the passing of ‘new-right’ employment legislation, such as the ECA 1991, the unitarist frame of reference was further strengthened. It has also been argued that more sophisticated unitarist ideas, promoted by a new breed of Human Resource Managers who are more likely to be university educated, are commonplace in large corporations and the public sector (Haworth, 1990 & 2012).

Different frames of references can also be linked to ideologies and different political parties. For example, employment relations policies by the National Party have often been inspired by unitarist assumptions, which is evident in both the Employment Contracts Act 1991 as well as the post-2008 changes to the Employment Relations Act (see Chapter 4). Traditionally, the Labour party has developed and promoted pluralist policies, of which the ERA 2000 is one example. However, an exception to the rule is how the Labour Government in the 1980s adopted market-based policies, sold state-owned assets and adopted more of a unitarist approach (see Chapter 3).

There have also been several important ways of developing the theoretical basis of frames of reference. Following the lead of Fox (1974), there have been different typologies that aim to explain how different management styles and strategies can impact on employment relations. These typologies are often based on managers’ attitudes to collectivism (Purcell, 1997; Sisson, 1989; see examples on the website from Rasmussen, 2009: 299). These attitudes have been researched in New Zealand where Geare et al. (2006 & 2009) found that managers had more pluralist attitudes when it concerned employment relations in general but exposed unitarist attitudes when it involved employment relations at their own workplace. This animosity towards collectivism and legislative restrictions on the managerial prerogative was also found in the research by Foster et al. (2009, 2011 & 2013) on the attitudes of New Zealand employers. It can partly explain the significant employer support of curtailing individual and collective employee rights under the 2008–2017 National-led governments (see Chapter 4).

Another theoretical development has been to expand the various conflict frames of reference. This has included the suggestion of a new neo-liberal, market-orientated management approach, called ‘egoist’ by Budd and Bhave (2008), illustrated by Table 2.2 below. This maybe a suitable addition in light of the decline of traditional employment relationships in many OECD economies (see Chapter 6). It also aligns with the comparative research of Baccaro and Howell (2011 & 2017) which finds that employer discretion has grown across OECD countries. Although Baccaro and Howell do not rely on frames of reference, their findings could be seen to provide a comparative, empirical support of the growing importance of egoist and neo-unitarist frames of reference since the 1980s.

| Approach | Key points of analysis | Ideological perspective |

| Neo-classical economics | Rational economic decisions by individuals based on market prices | Egoist |

| Human resource management | The organizational leadership and policies required to satisfy the psychological needs of employees | Unitarist |

| Marxism | Class struggle and control within the labour process | Radical |

| Employment relations | The rules that regulate the employment relationship | Pluralist |

Source: Bray et al., 2018, p. 17

In collaboration with other colleagues, John Budd has subsequently developed the conflict frames of reference further (see Budd, Colvin & Pohler, 2020) where interesting new angles are the application of these frames on employer and employee attitudes and linking them to diverse response patterns and conflicting interests. The frames of reference can also be intertwined with the traditional distinction between efficiency and equity (as explained below). For example, Budd and Colvin (2013: 13) have suggested that “the trilogy of efficiency, equity, and voice is a useful framework for considering the goals of conflict management in organization.” Overall, these developments of the conflict frames of reference draw on a number of multidisciplinary perspectives and insights and indicate how such multidisciplinary perspectives can be fruitful in adjusting theoretical understandings.

Multidisciplinary perspectives

Understanding different disciplinary perspectives is important in the study of employment relations for a number of reasons. First, it is important when reading employment relations texts or research reports to recognise the assumptions that the authors may be making and the particular biases, conscious or unconscious, that they may bring to the discussion of their subject matter. Secondly, it is necessary to recognise one’s own biases in approaching the study of employment relations – biases that may be derived from earlier courses of study in law, or economics, or sociology, or that may stem from particular work experiences, political attitudes and philosophies, or family and group pressures. Let us not imagine that we can eliminate such biases or indeed that we should strive to do so. Thirdly, it is necessary is to articulate our biases, to examine the ways in which they are likely to influence our approach to employment relations, and to understand how they may colour our discussions of employment relations issues. This articulation also allows other people to understand and evaluate our approach to employment relations.

There may be a variety of points of view on any single employment relations issue. As shown in Table 2.1, such points of view are often determined by the particular discipline that the observer or analyst is drawing upon. Let us look, for example, at the ways in which industrial stoppages may be ‘explained’ by the economist, the psychologist, the sociologist, the political scientist, and the lawyer. Table 2.1 caricatures some of the different perspectives that exist as each specialist seeks to explain a particular phenomenon – in this case the phenomenon of industrial stoppages (that is a strike if initiated by the employees, and a lockout if initiated by employers) – from within the frames of reference provided by his or her discipline. Moreover, within any single discipline there will be widely divergent ideological and philosophical positions as to the ‘cause’ of work stoppages.

Above all, it is important to understand that the most crucial aspect of the different disciplinary perspectives and personal biases that we each bring to the study of employment relations is that they determine the information we seek out, the methods of investigation we adopt, and the models we have in mind regarding the kinds of change that should be made in the practice of employment relations. For example, the economist in seeking to ‘explain’ industrial stoppages will look for some relationship between strike statistics and general economic indicators. He or she will want to know whether industrial stoppages increase or decrease significantly with changes in the level of employment, with changes in the rate of inflation, with changes in real disposable incomes or with changes in some other index of economic activity. Should some such significant relationship emerge from such research, the economist is likely to advocate courses of action by government to deal with problems of unemployment, inflation, or personal taxation in the expectation that policy changes in these areas will have some impact on industrial stoppages.

The psychologist, in contrast, in seeking to ‘explain’ industrial stoppages, will collect totally different kinds of data – his or her research being designed perhaps to establish whether or not there is some relationship between the numbers of industrial stoppages and the extent to which individual employees are satisfied with the nature of their work. The psychologist, too, will prescribe changes based on the evidence collected, except that his or her prescription is likely to be aimed at creating a more positive psychological relationship between the individual and the work that he or she does. The expectation is that the key to reducing the number of industrial stoppages lies in workplace relationships rather than in general economic, social, or political factors.

In essence, illustrating how each specialist discipline tends to define employment relations issues in a partial manner; how each collects and analyses information on the basis of restricted initial assumptions, and subsequently proposes policies or seeks solutions that are in turn a function of the assumptions or frames of reference established at the outset. While the reader should be aware that this selectivity is taking place as a result of the perspectives associated with different disciplines, there is no need to be unduly surprised by it. It is a necessary part of any academic or scientific study that some limitation has to be placed on the facts that are observed and on the information that is collected from the infinite mass available.

| ECONOMICS | Industrial stoppages are expressions of economic self-interest as employees strive to protect themselves against inflationary threats to their wages. Which employees will be involved in such stoppages will be determined largely by the bargaining power at their disposal; this bargaining power is, in turn, a result of imperfections in the labour market and the monopoly of skills by groups of employees. |

| PSYCHOLOGY | Industrial stoppages arise as a result of the behavioural eccentricities of the disputing parties, their inability to handle personality clashes, and their poor interpersonal relationships. The alienation of the employee from his or her work, lack of work satisfaction, lack of work motivation, and poor morale are all underlying causes of industrial unrest, as are outdated and inappropriate styles of management and supervision. |

| SOCIOLOGY | Industrial stoppages are the inevitable consequence of class and status divisions within our society and of the conflict of values between management’s demands for efficiency and the employee’s demands for fairness and equality of treatment. The growth of large-scale impersonal enterprises and organisations, and the extensive division of labour in those organisations, has increased the gap between management and workforce and accelerated overt forms of conflict. |

| POLITICAL SCIENCE | Industrial stoppages are the result of the differential distribution of power within industry and are the means by which the parties seek to impose control over each other. In some cases such stoppages may be part of broader political programmes or may arise because of politically motivated leadership within the trade union movement or within employers’ organisations. |

| LAW | Industrial stoppages are the result of the lack of effective disputes procedures, the inadequacies of the government’s mediation and conciliation machinery, and the disrespect of the disputant parties for the legal institutions and procedures available to them to resolve their differences. |

Source: Rasmussen, 2009, p. 34

Multidisciplinarity fosters theoretical tensions and dynamic growth

As Table 2.3 indicates there is a range of subject areas generated and influenced by the various disciplines. The legal perspective is clearly dominant in employment law. Because of the importance of the country’s long-standing statutory system of conciliation and arbitration, the legal perspective has had a particularly dominant influence on New Zealand’s employment relations traditions. Legal ideas and views impact on our current employment relations both through the precedents in common and employment law and through the various legislative frameworks that have been adopted over the years. The impact of economics on employment relations has been equally profound and many of the original pioneers of employment relations were economists. Key debates on the functioning of the labour market, on the economic impacts of unions and employment relations institutions, and on labour market flexibility have been driven and dominated by economists. In other areas, it is political theories and the viewpoints of political scientists and political philosophers that take centre stage; especially those dealing with the role of the state in employment relations.

It is important to stress that the multidisciplinary foundation of employment relations ensures that the topic and its research is forever changing. It is also the reason why, as mentioned in chapter 1, there are many ambiguities and unresolved issues since the various disciplines and the changing ideas within these disciplines constantly brings new angles to bear on the subject. There is an ongoing contest of ideas and explanations and this contest means that there is a useful debate in many areas of employment relations when it comes to explain particular issues and trends. These debates ensure a dynamic growth of the employment relations topic as illustrated in chapters 3 to 6. However, the downside is, as stressed in chapter 1, that employment relations becomes near impossible to cover in its entirety. There are always new issues, new explanations and new theoretical developments.

While the multidisciplinary nature of employment relations brings about a contest of ideas and theoretical angles, these ideas, models and theories do not appear out of thin air; they are normally grounded in fundamental economic, social and employment changes. These changes can be prompted by the business cycle, by fundamental labour market changes, by adjustments in social norms or by new technological breakthroughs. For example, the rise of the debate of work-life balance in the new millennium is based on fundamental economic, social and labour market changes: the influx of women in the labour market has been of key importance as have the changing family patterns; economic growth and rising living standards have been confronted with changing income and material expectations; the promise of new technology and economic growth bringing shorter working time contrasts with some people working very long hours and a considerable diversity in working time patterns. Thus, the very similar notion of work-life balance is rather complex as it can be viewed from many angles and its relevance has been prompted by fundamental societal changes. In the following, we will present an overview of some of these debates and theories that tend to cut across different disciplines.

As mentioned above, the two key ‘labour issues’ at the turn of the twentieth century were social order and social welfare. In New Zealand, these issues were associated with major industrial and political upheaval in the 1890s which prompted the introduction of the world’s first national conciliation and arbitration system in New Zealand in 1894 (see Chapter 3). The conciliation and arbitration system was primarily a way of ensuring social order – controlling strikes and lockouts – but its wage-fixing properties also contributed to beneficial working conditions and thus impacted on social welfare. The conciliation and arbitration system was a radical development but it also encapsulated fundamental issues associated with legal employment relations frameworks: what should the role and functions of the state be, how could collective bargaining and unions contribute positively (or viewed negatively: the effects be constrained), what kinds of dispute resolution would be most effective? As conditions and power balances changed, the ‘solutions’ to these issues shifted and new ‘solutions’ became the order of the day. This has become evidently so in the last 25 years with the legislative frameworks undergoing radical changes (see Chapters 3 & 4).

Chapters 3 to 6 indicate how the balance between the fundamental guiding principles of ‘efficiency and equity’ has shifted over time but also how the understandings underpinning the delivery of efficiency and equity have adjusted. These understandings have been influenced by the prevailing thinking of the day, but New Zealand employment has witnessed, in at least three instances, the implementation of radical solutions which has created considerable overseas interest. The main periods of ‘experimentation’ have been the 1890s, 1930s and 1990s. Faced with relative economic decline, New Zealand’s legislative framework has focused more on economic efficiency in recent decades. This has been capsulated in the prime objective of the ECA 1991 being an ‘efficient labour market’ and subsequently the prime objective of the ERA 2000 being ‘productive employment relationships’. Recent public policy fluctuations have also been prompted by changing opinions regarding how to obtain higher economic efficiency and how to best balance efficiency with fair bargaining and the protection of workers with limited labour market power (see Chapter 4 to 6). These changing opinions are also associated how higher productivity growth can be enhanced by more worker engagement, involvement and ‘voice’ (Budd & Colvin, 2013; Rasmussen & Tedestedt, 2017).

Since the early 1980s there has been a major shift in favour of individualism and workplace employment relations. While the current legislative framework – see the object clause of ERA 2000 (Figure 4.1 in Chapter 4) – has an explicit promotion of collective bargaining and unionism, a number of statutory individual employment entitlements were also introduced or enhanced and direct, individualised employer-employee relationships still played a crucial role. The focus on individualism has been associated with several interesting theoretical changes.

First, it has questioned the traditional understanding of collective action. With a more heterogeneous and transient workforce, it can often be difficult to fashion collective strategies and campaigns that are inclusive enough. This is a problem that several union movements have faced and new theories have tried to encapsulate how unions have attempted to cover several levels of employment relations (from the workplace to international arena – see Chapter 1) as well as develop a wider agenda which takes into account more social and individual concerns.

Second, the focus on individual behaviour and thinking can be found, as mentioned above, in theories on human resource managements, psychological contracts, emotional and aesthetic labour. These theories emphasise how employees ‘feel’ and ‘think’ of, or if seen from an employer’s view, should ‘feel’ and ‘think’. This can also be found in recent debates about work-life balance, careers and generational differences in work expectations.

Third, anti-discrimination and equal employment opportunity theories and models have prompted considerable changes in employment practices. While these debates may involve a group perspective the legislative interventions have often been about individual employment rights and entitlements.

The focus on workplace employment relations has made human resource management more crucial and also adjusted various human resource management approaches. The growing emphasis on organizational efficiency internationally has coincided with productivity being a major issue in New Zealand employment relations (see Chapter 6). The focus on productivity can also be detected in the recent popularity of strategic human resource management models building on resource-based view of the firm theories (Boxall & Purcell, 2011). This is aligned with the growing emphasis on building human capabilities within organisations and across the labour market. Because of its development mainly in the USA and the UK, the strong Anglo-American bias of human resource management has meant that recent emphasis on employee participation has mainly taken the weak informal, communicative forms (for example, ‘employee voice’). This is clearly less powerful when compared to formalised employee participation structures (see Chapter 6).

The popularity of the human resource management approach has been seen by many traditional ‘industrial relations’ academics as a threat. We regard it as just another example of how the employment relations field of study is continuingly evolving and being enlarged through its multidisciplinary approach. As can be seen from our definitional discussion in Chapter 1 and the multi-disciplinary perspective of this chapter, employment relations span a wide area of interest and covers several levels. In that respect, human resource management becomes a subset of employment relations field of study with its specific focus on organisational and management perspectives (Bray et al., 2018). However, human resource management scholars and practitioners are clearly pursuing their independent, field-specific research interests and thereby contribute to the continuous enlargement of the employment relations field of study. This has also encouraged employment relations scholars to move beyond their traditional focus on union and collective bargaining activities, which has also been prompted by the decline in union membership and collective bargaining in many OECD countries (Bray et al., 2018, p. 9).

Conclusion

This chapter has presented students with different theoretical positions and highlighted the positive impact of having competing position. A major part of the chapter has been devoted to the classical employment relations theories – systems approach and frames of reference (radical pluralism, pluralism, and unitarism) – as they present major research angles and basic understandings. While the discussion of these theories provides its own insights it is the continuous use of them which makes them important. There has been an emphasis, therefore, on providing examples on how the various perspectives are currently applied in employment relations debates. In some cases, this application can be obvious – such as the recent development of frames of reference – while in other cases this is less obvious (such as some of the developments of Dunlop’s system theory in comparative employment relations analyses).

The importance of the multi-disciplinary perspectives cannot be overstated as these perspectives have grown strongly in recent years. Different disciplinary perspectives often cloud the debate of employment relations issues as they are responsible for preferences of information sources and research approaches and they can lead to vastly different ‘solutions’. While this diversity can be frustrating it also promotes a healthy dose of theoretical debate and tensions which has prompted dynamic growth in theoretical perspectives and their application. It has meant that employment relations research has stayed relevant and forever changing. The drawbacks are that it makes it very difficult for researchers to keep up with theoretical advances and it promotes specialisation which erects barriers for multi-disciplinary understandings.

References

Bacarro, L. & Howell, C. (2011). ‘A Common Neoliberal Trajectory: The Transformation of Industrial Relations in Advanced Capitalism’. Politics & Society, 39(4), 521–564.

Baccaro, L. & Howell, C. (2017). Trajectories of Neoliberal Transformation: European Industrial Relations since the 1970s. Cambridge University Press.

Bamber, G.J. & Lansbury, R.D. (Eds.). (1998). International and Comparative Employment Relations: A Study of Industrialised Market Economies. Allan & Unwin.

Bray, M., Waring, P., Cooper, R. & Macneil, J. (2018). Employment Relations. 4th Edition, McGraw-Hill Education.

Bray, M. & Stewart, A. (2013). What Is Distinctive about the Fair Work Regime? Australian Journal of Labour Law, 26(1), 20–49.

Budd, J. & Bhave, D. (2008). Values, ideologies, and frames of reference in Industrial Relations. In Blyton. P., et. al. (Eds.). The Sage Handbook of Industrial Relations (pp. 92-113). Sage Publications.

Budd, J.W. & Colvin, A.J.S. (2013). The Goals and Assumptions of Conflict Management. In Roche, W. K., Teague, P. & Colvin, A. (Eds.). Oxford Handbook of Conflict Management (pp. 449-474). Oxford University Press.

Budd, J.W., Colvin, A.J.S & Pohler, D. (2020). Advancing Dispute Resolution by Understanding the Sources of Conflict: Towards an Integrated Framework. Industrial & Labor Relations Review, 73(2), 254-280.

Burke, R.J. & Richardsen, A.M. (2019). Creating Psychologically Healthy Workplaces. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Boxall, P. & Purcell, J. (2011). Strategy and Human Resource Management. Palgrave Macmillan.

Cummings, S., Bridgman, T., Hassard, J. & Rowlinson, M. (2017). A New History of Management. Cambridge University Press.

Deeks, J., Parker, J. & Ryan, R. (1994). Labour and Employment Relations in New Zealand. Prentice Hall.

Dibben, P., Klerck, G., & Wood, G. (2011). Employment relations: a critical and international approach. Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development.

Dunlop, J.T., (1958). Industrial Relations Systems. Harvard Business School Press Classic.

Dunlop, J.T. (1993). Industrial Relations Systems: Revised Edition. Harvard Business School Press.

Foster, B., Murrie, J. & Laird, I. (2009). It Takes Two to Tango: Evidence of a Decline in Institutional Industrial Relations in New Zealand. Employee Relations, 31(5), 503-514.

Foster, B., Rasmussen, E., Laird, I. and Murrie, J. (2011). Supportive legislation, unsupportive employers and collective bargaining in New Zealand. Relations Industrielles/Industrial Relations, 66(2), 192-212.

Foster, B., Rasmussen, E. & Coetzee, D. (2013). Ideology versus reality: New Zealand employer attitudes to legislative change of employment relations. New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 37(3), 50-64.

Fox, A. (1974). Beyond Contract: Work, Power and Trust Relations. Faber & Faber.

Frege, C., Kelly, J. & McGovern, P. (2011). Richard Hyman: Marxism, trade unionism and comparative employment relations. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 49(2), 209-30.

Geare, A., Edgar, F. & McAndrew, I. (2006). Employment relationships: ideology and HRM practice. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 17(7), 1190-1208.

Geare, A., Edgar, F. & McAndrew, I. (2009). Workplace Values and Beliefs: An Empirical Study of Ideology, High Commitment Management and Unionisation. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 20(5), 1146–1171.

Gittell, J.H. & Bamber, G.J., (2010). High-and low-road strategies for competing on costs and their implications for employment relations: International studies in the airline industry. International Journal of Human Resource Management. 21(2), 165–179.

Haworth, N. (1990). HRM – a Unitarist Renaissance? In Boxall, P. (Ed.) Function in Search of a Future: perspectives on contemporary human resource management in New Zealand (223-236). Longman Paul.

Haworth, N. (2012). Commentary: Reflections on high performance, partnership and the HR function in New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 37(3), 65-73.

Katz, H. & Darbishire, O. (2000). Converging Divergencies. ILR Press/Cornell University Press.

Kochan,T.A., Lansbury, R.D. & MacDuffie, J.P. (1997). After lean production: evolving employment practices in the world auto industry. ILR Press.

Purcell, J. (1987). Mapping management styles in employee relations. Journal of Management Studies, 24(5), 533-548.

Rasmussen, E., Bray, M. & Stewart, A. (2019). What is Distinctive about New Zealand’s Employment Relations Act 2000? Labour & Industry, 29(1), 52-73.

Rasmussen, E. & Tedestedt, R. (2017). Waves of interest in employment participation in New Zealand. In Anderson, G., with Geare, A., Rasmussen, E and Wilson, M. (Eds.) Transforming Workplace Relations (pp. 169-187). Victoria University Press.

Regini, M., Kitay, J. & Baethge, M. (1999). From Tellers to Sellers. MIT Press.

Sisson, K. (1989). Personal Management in Perspective. In Sisson, K. (Ed.) Personnel Management in Britain. Basil Blackwell.

Stone, R.J. (2018). Managing Human Resources. Wiley, 9th Edition.

Williamson, D. (2016). In Search of Consensus: A History of Employment Relations in the New Zealand Hotel Sector – 1955 to 2000. PhD Thesis, Auckland University of Technology.