3

- To present a historical overview of New Zealand’s employment relations pre-2000s, and the major changes and conflicts that have taken place over the last century

- To identify the prevailing economic, social and political ideologies that have shaped employment relations and significant pieces of employment legislation in New Zealand

- To discuss the impacts of the fundamental shift from a conciliation and arbitration system to decentralised and individualised bargaining processes

- To identify the changes to employment relations processes and outcomes under the Employment Contracts Act 1991

Introduction

Why are we interested in historical issues and trends when most governments, employers, managers, unions and workers are often focused on current challenges or looking forward to the near future? It is partly that a historical approach can answer the vital question: how did we end up here? This is of particular interest in employment relations which is often applied uniquely within national, industry or organisational levels. As such, historical and comparative trends are often used together to establish the relevance of current New Zealand trends and issues. It is also partly about being aware of past mistakes, past public policy directions and biases or negative side-effects of previous employment approaches. Finally, history provides a perspective on current issues whether they are about inequality, unemployment, union density, collective and individual bargaining or any of the myriad of employment relations issues and trends.

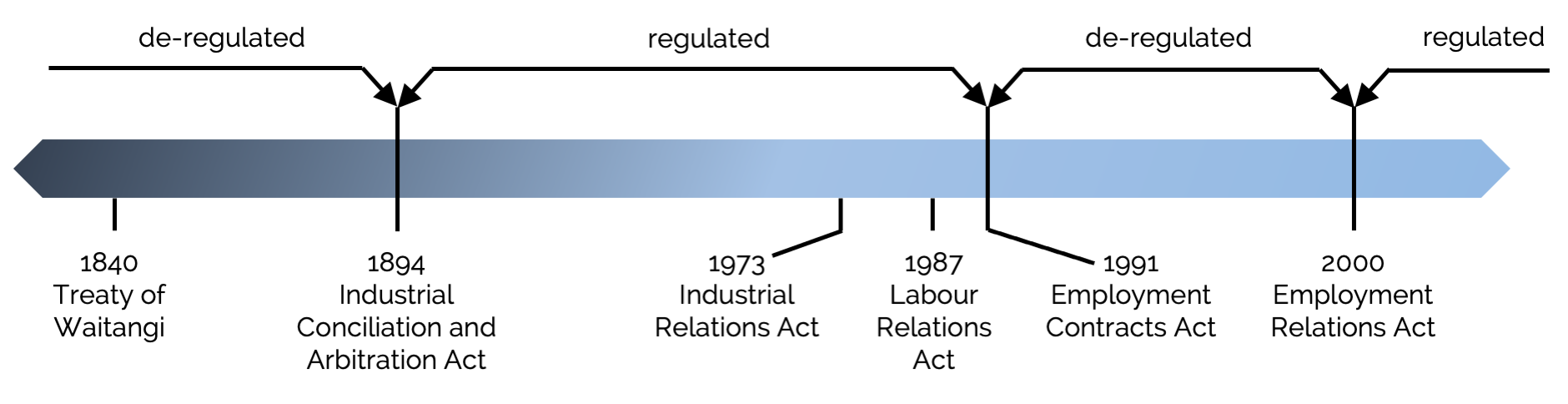

The history of employment relations in New Zealand is characterised by change, contest of ideas, political influence and power, and conflict, consensus and conciliation. Its development has been shaped by the prevailing economic, social and political ideologies (Wilson, 2017) and it has been influenced by trends and events in other countries, particularly the UK and Australia. An overview of New Zealand’s employment relations history is presented in Figure 3.1, using the major law reforms as historical markers of change. A more detailed overview can be found in Table 3.2 at the back of this chapter. Underscoring employment relations history is the oscillation from a deregulated labour market to a regulated labour market. This movement has not only affected the way New Zealanders have bargained over employment matters, whether on a collective or individual basis, but it has also influenced the balance of power between employers and employees and how workplace employment relations was conducted.

The chapter will describe some of the key turning points of the conciliation and arbitration system and will put emphasis on the 1970s and 1980s where many of the new ideas influencing current employment relations started to surface. As economic and social changes gathered pace in the 1980s, there was considerable pressure on employment relations to adapt to a more open economy, a changing labour force with different aspirations, and turbulent financial markets. While this started to challenge traditional collective bargaining and dispute resolution approaches, the demands for change also covered wider employment relations issues, such as occupational health and safety and equality and discrimination (see Chapter 5).

Finally, we will look in more detail at how employer pressure for further changes, together with a change in political power from a Labour to a National Government, resulted in passing of the Employment Contracts Act 1991 (ECA). The ECA 1991 constituted a ‘revolution’ of New Zealand employment relations and swept away key features associated with the nearly 100 year-old conciliation and arbitration system. In the era of the ECA 1991, a different employment relations philosophy took hold and, as shown in the next chapter, the ECA has also influenced the current legislation, the Employment Relations Act 2000 (ERA). Thus, we will discuss in more detail the key legislative changes in the 1990s and the major issues, processes and outcomes during this period.

Early conflict

During the 19th century, countries in the northern hemisphere were experiencing enormous upheavals in their political, social and economic structures. In particular, the British economic, political and social systems were not desirable so most immigrants to New Zealand were leaving for a better life. Many of the changes in Britain and Europe were influenced by ‘new’ technology and the shift from an agrarian-based to an industrial-based economy. These changes created a mass population movement of people to find factory work in towns and cities, but many were deprived of work and this created poverty and crime.

Early colonial settlement in New Zealand was characterised by labour shortages which enabled employees to bargain effectively with their employers for good wages and working conditions. Famously, an employment dispute developed in 1840 over the principle of the eight-hour working day. Samuel Duncan Parnell (1810-1890) is credited for winning this dispute at a time where there were shortages of skilled labour in New Zealand. Parnell was asked to build a store for a local merchant but he refused to work more than eight hours a day. The idea of working an eight-hour day soon spread throughout New Zealand, but it did not become law until 1936.

The period where employees enjoyed good bargaining power was short lived as an economic depression started in the mid-1870s and continued until the late 1890s. The depression period was characterised by high unemployment, deteriorating working conditions and a decline in wages. In response to public pressure over the exploitation of women and children working in factories, the Employment of Females Act 1873 was introduced. The Act focused on working conditions, the hours worked and, most importantly, the health and safety of factories. However, the Act made no provisions for adequate enforcement and, therefore, employers could disregard it, and mistreatment of workers continued at an alarming rate. In 1890, the Sweating Commission was established to investigate the exploitation of New Zealand workers. The Sweating Commission found many examples of poor working conditions and exploitative behaviours. One of the facts that the Commission uncovered was that, when workplaces became unionised, conditions for workers improved, wages did not sink below a living minimum and the hours of work were not excessive.

The Industrial Conciliation and Arbitration system

The new unions were neither experienced nor well-resourced and this made them susceptible to defeat in larger, drawn-out disputes. Their vulnerability was exposed in the trans-Tasman maritime dispute of 1890 which lasted 56 days and involved many industries and workplaces. It originally arose in Australia over the dismissal of a union delegate on a steamship and it quickly spread to New Zealand. The maritime strike was the first major national industrial dispute in New Zealand and ended in complete defeat for unions.

In the aftermath of the maritime strike, there was an overwhelming support from the trade unionists for the Liberal Government in the 1890 election. The new government came into power on a platform of social, political and economic reform. The Liberal Government introduced the structures of a regulated labour market with a legislative programme designed to protect employment conditions and to facilitate wage fixing reforms. The Minister of Labour, William Pember Reeves, introduced the most progressive and comprehensive labour regulation in the world (see below). New Factories Acts were also developed in 1891 and 1894. These Acts required all factories to be registered and it established the Department of Labour and the role of factory inspectors. The Acts gave prominence to occupational health and safety and provided, subsequently, a long-standing legal framework for employment relations, the so-called conciliation and arbitration system.

Industrial Conciliation and Arbitration Act 1894

William Pember Reeves was disenchanted with strike and lockout activity as highlighted by the maritime conflict in 1890 and believed that there had to be a better way of resolving conflict. The Industrial Conciliation and Arbitration (IC&A) Act was designed to facilitate the settlement of industrial disputes by conciliation and arbitration as well as to encourage the formation of industrial unions and employer associations. The major feature of the Act institutes the following bodies and measures:

- Conciliation Boards. The country was divided into districts in which Conciliation Boards were elected by employers and employees. Matters could either be referred to these Boards, or a Conciliation Board could conduct its own investigation into disputes. If the decision of the Board proved to be unsatisfactory, or if the Board failed to reach a decision, then either party in the dispute could appeal to the Arbitration court.

- Arbitration Court. The court consisted of a Supreme Court judge and two assessors elected by employers’ associations and trade unions. The court had power to hand down binding judgment in respect of wage settlement and work conditions. However, the conciliation and arbitration system did not affect farm or non-unionised labour.

- Registration of trade union. Unions gained the right to ‘exclusive jurisdiction’ in an industry if they were registered under the Act. Registration meant that unions became the legally recognised voice of workers. The Act introduced an ‘award system’, this consisted of the legal employment documents containing details of wage rates and working conditions. Unions were able to take their employers to the Conciliation Boards and the Arbitration Court to obtain awards. However, the unions could not go on strike and thereby put pressure on employers when they were registered under the Act.

The IC&A Act 1894 was intended to stimulate and protect unionism and safeguard the interests of employees. The registration of unions led to great increase in their numbers. The IC&A Act 1894 moved New Zealand from a country with a largely informal employment relations environment to one in which the state offered trade unions powerful statutory means to securing wage settlements with employers. As discussed in the turning points below, there were many changes to the original IC&A Act (also beyond those mentioned). It is simplification, therefore, when the IC&A system is presented as a uniform system, running from 1894 to 1991.

Turning point 1: The initial years of the conciliation and arbitration system

Between 1894 and 1906, there were no significant strikes. In the early years of the Arbitration Court, it granted wage increases and improved working conditions. It also facilitated a re-building of the unions and their membership. However, after the turn of the century, the Arbitration Court took an increasingly legalistic and restrictive stand. Some of the complaints from the unions regarding the decisions of the Court were: unfavourable awards, which were cautious, rather than generous, delays in court hearings and failure to conduct factory inspections to see that awards were properly enforced (Holt, 1986). Due to these issues with the IC&A system, there was a growing frustration among workers and trade unionists, and unions started to ignore the non-strike clause in IC&A Act 1894 or deregistered to rely on direct collective bargaining.

This made the conciliation and arbitration system more unstable as unions gained pay rises and better conditions in direct collective action, for example in the 1908 Blackball miners’ strike (Binney et al., 1990). Likewise, the First World War (1914-1918) had a major constraining labour market impact, as had various economic downturns and supply issues.

Turning point 2: The 1930s economic depression and reforms by the Labour Government from 1935 onwards

There had been economic stagnation in several years during the 1920s but the fall-out from the Wall Street share market crash turned into a full-blown economic depression during the 1930s. Like most western countries. New Zealand experienced economic decline, very high levels of unemployment, employer pressure to reduce wage levels and widespread poverty. In 1932, the Arbitration Court decided to implement a 10% general reduction in award wages, in line with a similar reduction in public sector wages. A subsequent amendment to the IC&A system also abolished compulsory arbitration which allowed employers to drive through further reductions in wage and working conditions (see Holt, 1986, pp. 185-189).

The Labour Party came to power in November 1935, 19 years after its formation. The newly elected Labour Government soon put through a series of employment reforms. These included restoring the compulsory powers of the Arbitration Court, making union membership compulsory, and allowing the registration of national unions as previously registration had been by district only. Restoring compulsory powers of the Arbitration Court, in effect, restored the Court’s authority. This authority allowed Arbitration Court to make legal decisions that often had more to do with the social and economic matters than with the existing employment situation (Deeks et al., 1994, p. 5).

The Arbitration Court decisions between the late 1930s and the mid-1970s were tied to the state benefit and full-time employment policies. This was clearly illustrated by the policy of keeping men in full-time employment at the expense of women’s employment (Du Plessis, 1993). In 1937, the Arbitration Court set minimum wages for women, for the first time, at 47% of men’s wages. This decision was in keeping with government policy which still maintained that a man, as head of the household, should be primary earner in order to support himself and his family. By 1949, the economy began to stall; the Labour Government ran out of steam after 14 years of being in power and was defeated in the 1949 general election by the National Party.

Turning point 3: The waterside dispute of 1951 and the strengthening of the Industrial Conciliation & Arbitration system

The Watersider dispute of 1951 was larger than all others in New Zealand’s employment history (Deeks et al., 1994, p. 52). This dispute was the longest, costliest and most widespread industrial confrontation in New Zealand history and lasted 151 days. When employers refused to pass the full 15% wage increase granted by the Arbitration Court to the waterside workers, the union leaders retaliated and imposed an overtime ban. The port employers threatened to dismiss the workers, who, in turn, responded by walking out.

Prior to the strike, more militant unions (led by the Waterside Workers Union) were angered by the lack of progress on the part of the Arbitration Court to increase wages and improve conditions, and the unions felt resentful about the impotence of the Federation of Labour (formed in 1937). The Federation of Labour backed the Labour Government’s economic policy of ‘stabilisation’ in which the IC&A Act played a key role by delivering static wages and conditions. The Federation of Labour even went so far as to support the National Government to force an end to the strike. However, this unusual position had more to do with supporting the IC&A system and an internal power struggle within the trade union movement than it was an endorsement of the employers’ and government’s stance. The newly elected National Government declared a state of emergency under the Public Safety Conservation Act and ‘brought in servicemen to work the wharves and helped new waterfront unions form under the protection of the police and armed forces’ (Deeks et al., 1994, p. 54) and deregistered the striking union.

Overall, many trade unions were dissatisfied with a system that did not allow them to take direct action in the form of strikes. The Arbitration Court worked well for unions in times of economic stability but not in an inflationary economic climate. In addition, the aftermath of the strike saw the penal sections of the IC&A Act strengthened. Strike action became illegal and hazardous for trade unions in terms of financial penalties.

Turning point 4: The Industrial Relations Act 1973

The IC&A system started to experience problems in the 1960s when inflation and full employment encouraged frequent negotiations and more workplace bargaining. The unions were also annoyed that the National Government had introduced voluntary unionism in 1961 (it had been compulsory since 1936). Several unions started to pursue more direct workplace bargaining and, in some cases, they also deregistered from IC&A system and relied on their own bargaining efforts. As a result, so-called ‘second-tier agreements’ became more significant, especially for larger employers, and this facilitated over-award, decentralised pay rises. The encouragement to pursue workplace bargaining was further enhanced when the Arbitration Court handed down a ‘nil order’ wage decision in 1968. While the unions and the employer associations managed, in unison, to overturn this decision in favour of a 5% wage decision, it clearly signalled to unions that they could not rely too much on wage increases obtained through the IC&A system.

The Industrial Relations Act 1973 tried to regain control over ‘second-tier agreements’ by incorporating direct wage bargaining into the legislative structure. Only registered unions could elect to bargain directly with the employer and achieve, subsequently, that these agreements were enforceable by the court. The Act also set fundamental definitional categories for industrial disputes to try to reduce collective action over interpretations of awards and collective agreements:

- Disputes of interests would arise when negotiating an award or a collective agreement. These disputes started a movement towards legalising strikes and lockouts which was further enhanced under the Labour Relations Act 1987 (see below).

- Disputes of rights occurred when an award or a collective agreement was already in place and the disputes concerned an interpretation of the content of an award or a collective agreement. These disputes were not allowed to be solved through industrial action but had to be dealt with within the Employment Institutions.

However, the Act failed to come to grips with the inflationary pressures fuelled by the ‘oil shocks’ of the 1970s. Not only did a tight labour market lead to endless bargaining, but the IC&A system became driven more and more by wage relativity considerations (James, 1986). Thus, the National Government became more and more involved directly in collective negotiations in an attempt to keep wage inflation under control.

Turning point 5: Decentralisation under the Fourth Labour Government, 1984-1990

In the early 1980s, economic pressures, many stemming from overseas, impacted strongly on New Zealand’s economy. Pressure to change New Zealand’s employment relations came from a number of quarters. The Treasury and the Reserve Bank wished New Zealand to progress with changes to bargaining structures and this was also supported by the Business Roundtable and the Employers Federation. The tripartite Long-Term Wage Reform Committee also advocated a more decentralised wage-setting system (Walsh, 1989).

While Australia had instituted an accord between the Labour Government and unions in 1983, public policy took a different direction in New Zealand. Following a sharp devaluation of the New Zealand dollar in the first days of the new Labour Government in 1984, it embarked on a very radical reform programme. These reforms, often called ‘Rogernomics’ after the Minister of Finance, Roger Douglas, or the ‘New Zealand Experiment’ (Kelsey, 1997), created a more open economy with reduced state subsidies and taxation and with fewer constraints on activities in most industries. The wave of economic reforms also enhanced pressures to reform employment relations. While the Industrial Relations Amendment Act 1984 had already replaced compulsory arbitration with voluntary arbitration (and thereby taken away the ability of weak unions to force employers to conclude awards and collective agreements), there were demands for further changes to bargaining processes and outcomes. In particular, there were employer demands for decentralised bargaining at enterprise level, changing or abolishing the awards system, and curtailing ‘blanket coverage’ which extended award coverage to all employers and employees in a particular industry or occupation (Rasmussen et al., 2019).

The Labour Relations Act 1987

The employment relations policy of the fourth Labour Government was based on an uneasy balance between allowing more direct bargaining and retaining the protective mechanisms of the IC&A system. This ‘two-handed’ approach continued through the 1980s. As a consequence, when the Labour Government introduced its Labour Relations Act 1987 (LRA), some key features of the existing law were retained.

On one hand, the LRA continued with the support of more decentralised bargaining and also supported direct bargaining by making the parties enforce their own agreements, widening the bargaining agenda to allow a greater choice of collective contracts and legalising lockouts and strikes. Employers and unions could also agree to remove themselves from award coverage and instead enter into negotiations of an enterprise agreement. On the other hand, there were considerable regulation of union and bargaining activities and unions were required to have more than a thousand members. Separate Employment Institutions were maintained in the form of a Mediation Service, Arbitration Commission and Labour Court. The Labour Government also strengthened the statutory minimum wage and introduced, subsequently, legislation on parental leave and pay equity.

In brief, the LRA 1987 could be seen as the gap between the old IC&A system and the employment regime of the 1990s. The LRA 1987 aligned with the Labour Government’s wider policy agenda since it shifted employment relations out of government control and into the hands of employers and employees. However, the relatively short existence of the LRA and some union unwillingness to engage in enterprise bargaining meant that the Act did not have much impact in terms of changing bargaining structure, processes and outcomes. Instead, this happened in dramatic fashion under the ECA 1991 (see below).

The state unions and the public sector reforms of the 1980s

Most of this chapter has been devoted to the developments in the private sector. However, it is also important to recognise the ongoing employment relations changes in the public sector. By 1980, more than a fifth of the labour force worked for the government, and the state unions were among the largest and most active in New Zealand. There were several major state unions, with the Public Service Association (PSA), the New Zealand Educational Institute and the Post Primary Teachers Association being the largest. The three distinctive features of public sector unions were the following:

- Membership was voluntary.

- Public sector unions operated outside the conciliation and arbitration system and negotiated directly with their employer, the government, and its department heads.

- Public servants were covered by specific employment legislation, commencing with the Public Service Act 1912 and culminating in the State Sector Act 1988.

Being a government employee or a ‘state servant’ was considered desirable as there were many benefits for the employees. Some of the benefits included reduced working hours, paid holidays, sickness leave and many others, though these benefits started to be eroded from the 1970s onwards.

The state service unions had been at the forefront of social reform. The PSA had a long history of challenging wage discrimination based on assumptions about women’s economic dependency. It also mounted a successful campaign for equal pay in the public service from the mid-1950s, which resulted in the passing of the Government Services Equal Pay Act 1960. This was eventually followed by the Equal Pay Act in 1972, which covered both the public and private sector workers. The continued existence of a gendered labour market made equal employment opportunities important. More than half of all employed women in the 1980s worked in just six occupations groups: nursing, teaching, typing, bookkeeping, cashiers, clerical and sales staff (New Zealand Department of Statistics, 1990). While public servants were pushing for equity between the sexes and ethnic groups and for reforms leading to equal opportunity, in general, they were falling behind in wages compared with their counterparts in the private sector, particularly in terms of managerial wage levels.

As the major economic and social changes were implemented under the Labour Government, this also influenced the public sector with key legislative changes being the State-Owned Enterprise (SOE) Act 1986, the State Sector Act 1988 and the local government reforms of 1989. These Acts aligned employment relations in the public sector with private sector employment relations, including collective bargaining disputes resolution, and the public sector was leading the drift towards bargaining at enterprise level.

The SOE Act 1986 created nine corporate enterprises involved in broadcasting, electricity, forestry, banking, post and telecommunication. This marked the beginning of the dismantling of this part of the public sector, with a loss of more than 40,000 permanent jobs between 1987 and 1989. These changes had profound implications for employment relations and, according to Walsh and Wetzel (1993), it changed the structure of collective bargaining processes and the unions’ role in decision making in SOEs. Subsequently, many of the SOEs were privatised (see Spicer et al., 1996).

The State Sector Act 1988 also facilitated a shift from sector to enterprise bargaining. However, the strong coordination role of the State Service Commission meant that the bargaining processes and outcomes changed less, compared to changes amongst the SOEs. Still, the enterprise focus allowed for diverse pay and conditions amongst managerial staff and undermined the notion of a state sector career.

Finally, the 1989 local government reforms amalgamated local government bodies into larger units and also allowed local government bodies more leeway in developing their own economic strategies (see Bush, 1995). This prompted considerable employment relations changes, with more diverse bargaining processes and outcomes, partly resulting from experiments with new employment arrangements and outsourcing of work.

Employment relations in the 1990s

The Labour Government attempted to follow a ‘two-handed approach’ in the 1980s in order to achieve both a decentralisation of bargaining arrangements and a protection of weak employee groups. Employer pressure for further change, together with a change in political power from a Labour to a National Government, resulted in the passing of the ECA 1991. This represented a dramatic shift in employment relations philosophy, bringing to employment relations the same deregulation and market focus that other parts of the economy had experienced since 1984.

Some of the changes following the ECA’s implementation were expected while others were not. The decline in union density and in collective employment contracts followed the predicted path. It was also anticipated that employees in the secondary labour market would fare less well in a deregulated labour market and that there would be a diversity in bargaining outcomes.[1] However, it is difficult to ascertain which changes in bargaining outcomes can be attributed to the ECA 1991, which ones can be attributed to delayed effects of the previous legislative changes, and which could be regarded, as a result of wider economic conditions. Growth in productivity was disappointingly low under the ECA, a surprise to those who blamed New Zealand’s low productivity growth on the labour market inflexibilities and union monopolies of the previous regime.

The ECA 1991 made employment law a key employment relations topic in the 1990s. The Act brought the notion of employment contracts to the forefront of the debate. As all employees had access to minimum employment rights, including the personal grievance option, the distinction between an employee and a contractor became crucial (see Chapter 1). Although the ECA 1991 set the broad parameters for employment relations behaviour in the 1990s, the non-prescriptive nature of the Act made case law and the legal precedent-setting important. However, the resulting drawn-out and often confusing changes associated with legal precedent made planning difficult for employers and employees alike. The many cases before the Employment Tribunal indicated a shift towards individualised bargaining and dispute processes and this, in turn, raised the questions of whether such a trend towards litigation was beneficial and whether it would bring about efficient workplace practices. By 1999, the Employment Tribunal had a large backlog of cases, and rulings took up to a year to be delivered (Te Ara, 2018, p. 10).

The shift in employment relations philosophy

With the post-1984 economic and social reforms, considerable philosophical debate started about which principles should underpin employment relations. The principles governing employment relations prior to 1984 were derived, in broad terms, from the intellectual tradition associated with Keynesian economic policies, state intervention and welfare state provisions. A tripartite pluralism was often the explicit goal. That is, the state provided a legislative framework which promoted a balance of interests between employers and employees. This was encapsulated in the award structure and its collective bargaining process. It was understood by proponents of that framework that the only context in which individuals could confront, on an equal footing, the relatively more powerful employers in negotiations was through the effective collective organisation of individual employees.

As we saw earlier in this chapter, there was mounting frustration over the inability of the IC&A system to deliver efficient results across the labour market. It became evident in the 1980s that the traditional consensus surrounding employment relations had begun to evaporate and that the latent conflict between centralisation and decentralisation was coming to the fore. A comparison of the basic assumptions of the arbitration system with those of the deregulated labour market approach illustrate interesting philosophical differences. The arbitration system assumed that the employment relationship was a special one – that it differed from a standard market exchange relationship – and that it was one which required some measure of state regulation and involvement (Deeks et al., 1994, p. 82; Walsh, 1993, p. 176).

However, the proponents of labour market deregulation (e.g. Brook, 1990 & 1991) argued that:

- the employment relationship is a private contractual relationship between two parties;

- with the notion of individual choice being promoted, contractual arrangements should have few limits as long as both parties agree;

- beyond supporting fair market exchanges, the state should refrain from labour market interventions;

- supporting fair market exchanges implies restricting or abolishing the monopoly rights of unions.

The question of power imbalance was either not discussed or seen to be solved through other contracting possibilities (for example, having a ‘bargaining agent’).

Thus, the deregulation approach entailed abandoning the traditional balance between efficiency and equity since market solutions were expected to provide adequate equity outcomes over time. In the rare instances where this did not occur, shortcomings could be better compensated through tax or income transfer policies than through direct labour market interventions. The enactment of the ECA 1991 epitomised this philosophical shift by introducing substantial deregulation of bargaining structures and processes. It rejected many of the principles associated with the IC&A system.

Deregulation of employment relations was relentlessly promoted by the business lobby group, the Business Roundtable (Harris & Twiname, 1998), and found at least some support within many business groups. The favoured outcomes of the Business Roundtable were an ‘employment at will’ situation with limited or no restrictions on a direct exchange between employer and employee (Walsh & Ryan, 1993).

The Employment Contracts Act 1991

The ECA focused on efficiency and emphasised that parties have wide-ranging choices in terms of organisational affiliation and bargaining arrangements. This was clearly stipulated in the Act’s long title:

‘An Act to promote an efficient labour market and, in particular

(a) To provide for freedom of association;

(b) To allow employees to determine who should represent their interests in relation to employment issues;

(c) To enable each employee to choose either

(i) To negotiate an individual employment contract with his or her employer; or

(ii) To be bound by a collective employment contract to which his or her employer is a party;

(d) To enable each employer to choose

(i) To negotiate an individual employment contract with any employee;

(ii) To negotiate or to elect to be bound by a collective employment contract that binds two or more employees;

(e) To establish that the question of whether employment contracts are individual or collective or both is itself a matter for negotiation by the parties themselves.’

The ECA constituted a dramatic shift in employment relations – away from the collectivist traditions of the past – by promoting the rights of individual employees and employers. It abolished the award system and union preference rights, and promoted an enterprise-bargaining model in both private and public sectors. The emphasis on individualism and individual choice was promoted in several ways. It was made explicit in Part I of the Act that the individual had an unfettered choice of whether or not to join a union and no undue influence or preferential treatment were allowed by either employers, employees or unions in order to promote or prevent union membership. The individual focus was also bolstered through the notions of employee representatives (‘bargaining agents’), authorisation and ratification of contracts, and personal grievances which all made the individual employee the ‘actor’.

The individual focus was further enhanced by making collective bargaining more difficult under the Act. There were a number of new terms concerning authorisation, access to employees, ratification procedures and the extension of collective employment contracts. These new terms made it easy for employers to obstruct the unions’ collective bargaining attempts as the unions would have had to clarify the meanings of the new terms through court action. However, the major stumbling block for collective bargaining was that it was unlawful to stage collective action when pursuing a multi-employer contract. This made it near impossible for the unions to continue with industry- or occupation-based multi-employer collective contracts. This restriction was probably in breach of New Zealand’s obligations under the International Labour Code (Haworth & Hughes, 1995; Wilson, 2000). It is no wonder, then, that collective bargaining and union density dropped dramatically under the ECA, as detailed below.

However, Walsh (1993) noted that while the ECA greatly diminished the role of statutory regulation of collective bargaining, it did retain and expand a limited range of employment conditions. The Act also covered all employees, whether they were on collective or individual employment contracts, and across both public and the private sectors. Previously, employees on individual employment contracts were outside the employment relations framework and, as mentioned above, many ‘primary labour market’ employees came under labour law jurisdiction for the first time with the passing of the ECA.

The ECA’s Employment Institutions were relatively similar to the traditional labour institutions under the IC&A system. It provided a strong role for the existing legacy of legal precedence; procedural fairness was crucial in the area of dismissals; the fines and jurisdiction available were substantial; and personal grievances could relatively easily be pursued through the Employment Institutions (Walsh, 1993; Grills, 1994). It also gave mediation a larger role in dispute resolution. The growth in personal grievance cases and mediation’s larger role meant that the Employment Institutions played a crucial, more politicised role under the ECA (Rasmussen & Greenwood, 2014; Walsh, 1993).

Outcomes: union density and collective bargaining

New Zealand has no regular, comprehensive workplace surveys, making longitudinal assessments of changes in workplace practices and employment conditions harder to establish. In particular, information about trends in the secondary labour market has been limited (McLaughlin, 2000). Thus, one has to be cautious in aligning labour market changes, beyond changes to collective bargaining and union density, to the impact of the ECA.

The ECA led to a decline in union density (union members as a percentage of the workforce). Union membership fell sharply following the ECA’s introduction and continued to fall throughout the decade. This decline meant that there was often no union presence in many workplaces in the private sector. In these workplaces, there was no real collective bargaining option available to employees since the expected influx of non-union bargaining agents did not occur. It was only in their traditional strongholds (including the public sector) that the unions kept collective bargaining alive and only there that the unions managed to maintain their representative status.

The advent of the ECA saw changes to bargaining processes and practices, with a move away from collective employment contracts towards individual employment contracts. Prior to the passing of the Act, it was estimated that collective employment contracts covered around 56% to 60% of employees. By February 1992, 45.6% of all those employed were on individual employment contracts, which increased to 56.6% in February 1993 (Statistics New Zealand, 1994, p. 133). Even so, the collective bargaining coverage was probably inflated since it included so-called ‘collective contracting’ under the ECA; that is, collective employment contracts developed (without union negotiations) by the employer and then signed subsequently by employees (Dannin, 1997; Gilson & Wagar, 1998).

| Month | Year | Unions | Membership | Density |

| December | 1985 | 259 | 683 006 | 43.5% |

| September | 1989 | 112 | 648 825 | 44.7% |

| May | 1991 | 80 | 603 118 | 41.5% |

| December | 1991 | 66 | 514 325 | 35.4% |

| December | 1992 | 58 | 428 160 | 28.8% |

| December | 1993 | 67 | 409 112 | 26.8% |

| December | 1994 | 82 | 375 906 | 23.4% |

| December | 1995 | 82 | 362 200 | 21.7% |

| December | 1996 | 83 | 338 967 | 19.9% |

| December | 1997 | 80 | 327 800 | 18.8% |

| December | 1998 | 83 | 306 687 | 17.7% |

| December | 1999 | 82 | 302 405 | 17.0% |

Source: Crawford et al., 2000, p. 294

The level of industrial stoppages was moderate under the ECA, when compared with the situation in the previous decade. The low level of industrial stoppages was probably influenced by the weaker position of the union movement and the fact that the ECA introduced further restrictions on strike actions, including strike action being unlawful in pursuit of a multi-employer collective employment contract. On the other hand, some employers became more aggressive in their negotiation tactics and lockouts, or the threat of lockouts became more important in the first years of the ECA. This included so-called partial lockouts where employees are not locked out of the workplace but the employer withholds one or more of their employment conditions, such as overtime payments, until a settlement is reached. Partial lockouts were first deemed lawful in 1992, but a June 1994 Employment Court decision reversed that legality and, subsequently, occurrence of partial lockouts declined significantly.

Outcomes: the changing status of employment law in the 1990s

The non-prescriptive nature of the ECA meant that there were few directions on how to conduct an employment relationship. As the Act represented a sharp break with the previous conciliation and arbitration system, it contained many new terms which had either vague or no prescribed legal meaning. Therefore, legal decisions taken in the Employment Tribunal, Employment Court and Court of Appeal had a significant impact on the development of employment relations under the ECA.

Reaching legal decisions entails a detailed examination of particular practices and such decisions can establish a well-founded view on a workplace problem over time. However, the constant process of litigation was rather costly (commentators have pointed to lawyers as the major beneficiaries of the ECA – see MacDonald, 1994), and it took considerable time to develop a sufficiently large body of case law to establish benchmarks for the major types of employment relations practices. This also means that individual cases can cause confusion about what is an appropriate, lawful employment relations practice. Under the ECA, this confusion was understandable, since the courts sometimes came to rather different conclusions about similar practices. This was the case in areas of redundancy, fixed-term employment contracts and holidays entitlements and, as highlighted above, it had a significant impact on the use of lockouts in the 1990s.

While the ECA saw a sharp decline in collective bargaining and union density, employees in the ‘primary labour market’ had more leverage, leading to a high level of individual disputes with personal grievance rights becoming central in employment relations. The Act afforded employees the opportunity to decide themselves whether they would lodge a personal grievance claim, whereas previously, the claims procedure had to be conducted through unions. Well-publicised decisions awarding significant compensation to senior or managerial employees influenced some managers to become more careful regarding substantive and procedural fairness in dealings with their staff.

Under the ECA, the idea of a fair process, also known as procedural fairness, received a lot of attention. Key elements of a fair process are a discussion of the issues at stake between employer and employee and issue clarity. These key elements are important as each party should understand the other’s position and also what changes and outcomes are sought. Procedural fairness includes giving the employee the opportunity to rectify the problem and making sure the employee understands that he/she could be dismissed if the problem is not solved. In other words, the employee should be aware of the exact problem and know how to rectify it and be given adequate time to do so (see Chapter 1). In such situations, procedural fairness is important and, if not followed carefully, can lead to a personal grievance being lodged.

The rising number of personal grievance cases in the 1990s and the confusion surrounding justifiable dismissals raised doubts about the efficiency of the non-prescriptive nature of the ECA. This meant that there was a lack of adequate guidelines for satisfactory employer and employee behaviour. Instead, the process of developing legal precedent – that is, court decisions on key legal issues – was used to formulate more precise guidelines. This was a long-winded and litigious process and could be difficult to understand for the average employer and employee.

Outcomes: key labour market changes during the 1990s

When it comes to the changes that occurred in wages, wage dispersion and other employment conditions in the 1990s, it is important to stress that these changes were not attributable, either directly or indirectly, to any single factor. The ECA 1991 had an important impact, but so did other changes in the New Zealand economy, such as economic activity and demographic changes. Any suggested causality between trends in labour market indicators and the impact of the ECA needs to be critically examined.

Although average hourly wages increased every year in the 1990s, these increases were initially matched by increases in the Consumer Prices Index for the first part of the 1990s, and then real wages increased slowly in the second half of the 1990s. During the ECA’s first two years, the expectation of increased wage dispersion (that is, a growing difference between high and low wage levels) resurfaced in frequent media reports, as did reports of widespread abolitions and reductions in penal rates and overtime payments. The biggest effects of these cuts were felt in those areas of the labour market in which penal rates and overtime payments constituted a major part of wage packages, such as low-wage areas of retailing, hospitality, cleaning and caregiving.

There were major changes in working hours in the 1990s, with a tendency towards longer working hours amongst full-time employees and a rise in the number of people working part-time. In the 1990s, the 40-hour working week was no longer the prevailing norm. The workforce was split roughly into three parts, with around a third normally working less than 40 hours, another third working 40 hours and the remaining third working in excess of 40 hours per week. Several indicators pointed to a substantial increase in working time: full-time employees worked, on average, more hours per week; there were more people working very long hours, and there were more people with more than one job. It is difficult to see how this move towards longer working hours can accommodate the fashionable notion of balancing work and family life or allow time for continuous upskilling and re-education.

On the other hand, the number of people working part-time also increased, with female employees accounting for more than two-thirds of this increase. While part-time employment suits many people with family responsibilities, there are negative aspects to it, such as limited income, fewer career prospects and reduced training opportunities. Many employees also found it difficult to plan working hours as casualisation, on-call arrangements and split-shifts became more common (Brosnan & Walsh, 1998). McLaughlin (2000) found in his survey of employees in the retail sector that such employees had a limited choice regarding the scheduling of their working hours and many reported that their hours of work had a detrimental impact on their family life.

While most new jobs created were still full-time ones, there was a strong rise in ‘non-standard’ types of employment, such as an increase in multiple job holders and people working on either a casual or a fixed-term basis. The number of people employed in both the primary and secondary sectors of the economy declined significantly while employment in the service sector increased by nearly 20%. It was within the expanding service sector of the economy that most non-standard work was created.

An increase in non-standard employment has far-reaching implications for the individuals concerned (Brosnan & Walsh, 1998). It can provide an opportunity to tailor one’s working patterns to family or personal interests, it may open the way for new career options and it can be an option when faced with unemployment (Alach & Inkson, 2004). However, it has been suggested that many of the new ‘non-standard’ work practices may simply be a way for employers to cut costs, with some of these costs and insecurities being passed onto individuals. This has been especially true in the case of self-employed contractors. They are not protected by employment law as they are not classified as employees and, consequently, they are not entitled to related benefits. The costs for the individuals concerned are many and varied and include: unpredictability of income; no payment of mandatory employee-related benefits (e.g. holiday pay, sick pay, statutory holiday pay); no provision of training; limited ongoing professional advancement and development (Burgess & Connell, 2004). In some cases, there are also negative social implications, such as inconvenient or long working hours and the inability to plan family and leisure time.

Unemployment levels fluctuated a great deal under the ECA but stayed at a concerning high level for most of the 1990s. At the same time, there was a sharp increase in the number of people on other types of benefits. Despite changes in employment relations and the benefit cuts of the early 1990s (Boston & Dalziel, 1992), it was necessary for the government to devote further attention to unemployment and social welfare problems. This included the 1995 Employment Task Force reports, the 1998 ‘work fare’ scheme for unemployed people, and changes to welfare benefits announced in the 1998 budget (Rasmussen & Lamm, 2000).

Outcomes: the unfulfilled expectations of stronger productivity growth

One of the well-published purposes of the ECA was to encourage increased national labour productivity by combining changes in the labour market with the already started economic reforms.

‘By introducing voluntary unionism and changing bargaining procedures it will increase productivity, enhance employment and encourage the sharing of benefits that flow from increased output’ (National Party, 1990, p. 27).

However, the Act fell short of these expectations. Although there were many reports of increased productivity within individual organisations, it caused alarm when dismal national labour productivity figures started to appear in the mid-1990s (for an overview of estimates, see Rasmussen, 2009, p. 449).[2] The exact reasons for the low productivity in New Zealand were puzzling and no single obvious explanation was forthcoming. Among the factors being blamed were: inadequate investment in infrastructure (roads, electrical power generation, public transport systems, etc.), insufficient investment in training and education, and lack of positive synergy between the various reforms.

The main reason behind the positive expectations was that it was assumed by proponents of the ECA 1991 that productivity growth was limited by restrictive workplace practices instituted by the award system and union activity. This assumption was even shared by some opponents of the ECA (Easton, 1997, p. 12). As the abolition of the award system and the weakening of union influence did not lead to major productivity increases, other explanations were sought. Instead of union practices, some commentators put the spotlight on the efficiency of management practices in New Zealand (Rasmussen, 2009).

On a theoretical level, the pinpointing of union practices as the culprit for the productivity problems prior to 1990 is in accordance with classical economic models (e.g. Brook, 1990). These models view unions as monopolists who introduce inefficient restrictions on work practices and extract excessive wage increases. The compression of wage differences pursued by many unions is also regarded as damaging to productivity since it can block the efficient allocation of labour – people are not encouraged to shift from low-productivity organisations (paying low wages) to high-productivity organisations (paying high wages).

However, the assumption that union activity always has a negative impact on productivity has been strongly criticised. The counter-attack has underlined the positive effects of union activity (e.g. Freeman & Medoff, 1984). These positive effects can include a reduction in staff turnover because the union is able to make management aware of employee dissatisfaction (the so-called collective or union ‘voice’), an upwards pressure on labour costs may induce the employer to implement more efficient labour processes, and union-management collaboration to create more efficient workplace practices can also be very beneficial (Peetz, 1998). This could explain why some countries with a high union density rate, for example the Scandinavian countries, have high productivity levels. Thus, the type of union actions and the setting in which unions operate will often determine the actual impact they have on productivity.

Conclusion

New Zealand’s employment relations history is characterised by conflict, conciliation and change. While employment relations began historically with individual bargaining, some individual rights, and traditional employer-employee conflicts, this changed in the 1890s. Then, there was a realisation that conflict could be managed through a formalised conciliation and arbitration system which recognised the collective rights of both employees and employers. The conciliation and arbitration system lasted, with considerable modifications, nearly 100 years. Unsurprisingly, this longevity meant that there were many contextual changes as war, different governments, economic cycles and social pressures all influenced changes to the conciliation and arbitration system. This prompted numerous ‘fine tunings’ and more substantial changes of the legislative frameworks underpinning the conciliation and arbitration system and, at the end of the 1980s, there had clearly been a considerable shift towards a somewhat different legislative framework.

However, the long reign of the conciliation and arbitration system created a number of ingrained approaches and structures (Rasmussen, 2009, pp. 61-64):

- The legalistic process encouraged an adversarial process;

- The unions’ ability to have exclusive bargaining rights through their registrations – and not because of industrial strength – fostered many and weak unions;

- The extension of bargaining outcomes through ‘blanket coverage’ of industry or occupations meant that many employers were not involved in negotiations;

- Specialised Employment Institutions – for example Conciliation Boards and the Arbitration Court – dealt with negotiations and industrial disputes;

- Individual employment agreements were outside the conciliation and arbitration system and instead they were dealt with under common law jurisdiction;

- Bargaining was restricted to a number of narrowly defined issues (‘industrial matters’) which limited the demands of the unions and their possible involvement in managerial issues.

Generally, the inability of the conciliation and arbitration system to implement fast and flexible wage adjustments in both upwards and downwards directions was always its weakest point during inflationary and deflationary periods, and this inability became the catalyst for change. The growing focus on pay relativities and the lack of widespread workplace bargaining made the conciliation and arbitration system less suited to an economy integrated into world markets, and this prompted demands for more direct, decentralised bargaining as other parts of the economy was deregulated. Initially, the public sector was leading the way towards decentralised collective bargaining and workplace employment relations. In the private sector, the Labour Relations Act 1987 had less impact than had been expected and this, together with an economic recession, increased the pressure for further change in the 1990s.

The chapter discussed in detail the revolutionary changes facilitated by the ECA. These changes were driven by economic pressures, a different employment relations philosophy and a very different, non-prescriptive legislative framework. This prompted a shift from collective to individual bargaining and towards workplace arrangements. The associated sharp decline in collective bargaining and union density may have been expected, though it also facilitated a high level of individual disputes with personal grievance rights becoming central to employment relations. More surprising (for some) was the disappointing productivity growth and questions arose why this was the case when the supposed culprits of unions, collective agreements and inflexible working practices had much less influence in the 1990s.

In hindsight, the first half of the 1990s marked the high watermark of neo-liberalist, free-market reforms. The general unhappiness with radical reforms prompted a surprising outcome of a 1993 referendum on New Zealand’s electoral system with a proportional electoral system (Mixed Member Proportional – MMP) being implemented in the 1996 general election. The radical public sector reforms came under attack from the mid-1990s (especially after the so-called ‘Schick Report’ in 1996), and were slowly adjusted (Boston, 1999). The ECA 1991 continued to be a controversial, unpopular approach throughout the 1990s. As market-driven, contractual approaches came under attack at the end of the 1990s, the change in government heralded, as will be discussed in the next chapter, another major change in employment relations.

| Historical developments and events | Reasons for changes/events and consequences |

| Early Settlers in mid-1800s had good bargaining position | Labour shortages enabled employees to bargain effectively with employers for good wages and working conditions |

| First employment conflict, involving Parnell in 1840 | Disputes over working hours during a time of skilled labour shortages. Parnell won the 8-hour working day (seen as the origin of Labour Day). |

| Economic depression in late 19th century (1870s to early 1890s) | High unemployment affected working conditions and wages decline. Longer hours were common and boys and girls often worked. |

| Introduction of Employment of Females Act 1873 | This Act was enacted due to public pressure over exploitation of women and children working in factories. However, the Act made no provisions for adequate enforcement and employers often disregarded regulations. |

| Late 19th century was a time of strong support for trade unions | Reaction to economic depression, exploitation of workers and dire working conditions. |

| 1890 Maritime dispute in Australia that spread to New Zealand. This was the first major national industrial dispute in New Zealand | Arose in Australia over dismissal of union member. Maritime dispute lasted for 56 days. Dispute ended in complete defeat for the participating unions and their supporters.

Consequences: employers were able to make non-unionism a condition of work; if employees were found to be in connection with trade unions, they could be dismissed instantly. |

| Factories Act 1981 and 1894. Right to inspect factories and wage books | The Liberal Government introduced structures of regulated labour market. Legislation designed to protect employment conditions and facilitate wage fixing reform. Factories Act required all factories to be registered. The Act established Department of Labour which had the role of factory inspection. |

| Industrial Conciliation and Arbitration (IC&A) Act 1894. Act designed to facilitate the settlement of industrial disputes | Influenced by maritime conflict of 1890. Act dealt with strikes and lock-out activity. Sought to protect and promote unions and safeguard the interests of employees. Encouraged formation of industrial and employer associations. Unions gained strength.

Features of the Act:

|

| 1894–1906 no significant strikes | Stability – the IC&A Act seems to work. |

| 1908 Blackball miners’ strike. Tension between employers and unions | Poor working conditions in the mine, with main issue being an unreasonable time (15 minutes) for meal breaks.

A 3-month strike ends in union victory which changes unions’ attitude to IC&A system. Non-registration allows unions to strike and negotiate directly with employers. |

| Before WW1 in 1914 |

|

| 1920s Economic Downturn | High rate of unemployment and inflation.

Decisions handed down by Arbitration Court during this time restricted adjustment of wages and conditions. During the 1920s economic downturn, the Arbitration system weakened |

| 1935 Labour Party in power | Compulsory powers of the Arbitration Court restored. Arbitration Court could also make legal decisions based on social and economic factors rather than just employment.

Union membership made compulsory. |

| 1937 Arbitration Court sets minimum wage for women but constitutes only 47% of men’s minimum wage | Introduction of the minimum wage was set in line with government policy which maintained that men were heads of household; thus, women were paid considerably less than men. |

| 1951 Waterside dispute | National Party in government after defeat of Labour Government in 1949.

Unions unhappy with Arbitration Court progress to settle wage disputes and improve conditions. Employers’ refusal to pass on a 15% wage increase granted by Arbitration Court to waterside workers led to longest, costliest and most widespread industrial confrontation in New Zealand history. Lasted 5 months and cost 42 million pounds. |

| 1950s/1960s/1970s recorded an increase in workplace bargaining | Wage settlements under the IC&A system often included additional local agreements (known as ‘second tier’ agreement). These decentralised pay rises undermined the IC&A system, especially after the infamous ‘Nil Decision’ by the Arbitration Court was overturned in 1968. |

| The Industrial Relations Act 1973 | ‘Second tier’ agreements based on direct wage bargaining are incorporated into legislative structure.

Only registered unions could elect to bargain directly with employer and achieve agreements enforceable by courts. Industrial Relations Act failed to come to grips with inflationary pressure of the 1970s oil shocks. |

| Labour Relations Act 1987 | Economic and public policy pressures due to international changes in overseas markets (e.g. Britain joining the EU and the 1970s oil crises). Major reforms post-1984: the New Zealand deregulation ‘experiment’.

Employers pressured for deregulated labour market. Unions believed that workplace bargaining would result in lower wages and high unemployment rate. This pressure led the Labour Government to introduce the Labour Relations Act 1987. Features of the Act included:

|

Source: Originally developed by Shivashni Priya Singh in 2013; subsequently amended by authors.

References

Alach, P. & Inkson, K. (2004). The new ‘Office Temp’: Alternative models of contingent labour. New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 29(3), 37-52.

Binney, J., Bassett, J. & Olssen, E. (1990). The people and the land: Te Tangata me Te Whanau. Allen & Unwin.

Boston, J. (1999). New models of Public Management: the New Zealand case. Samfundsøkonomen, 5, 5-15.

Boston, J. & Dalziel, P. (1992). The Decent Society: Radical Politics in New Zealand. Oxford University Press.

Brook, P. (1990). Freedom at Work. Oxford University Press.

Brook, P. (1991). New Zealand’s Employment Contracts Act: An incomplete revolution. Policy, 7(3), 12-14.

Brosnan, P. & Walsh, P. (1998). Employment Security in Australia and New Zealand. Labour & Industry, 8(3), 23-41.

Burgess, J. & Connell, J. (Eds). (2004). International Perspectives on Temp Agencies and Workers. Routledge.

Bush, G. (1995). Local Government and Politics in New Zealand. Auckland University Press.

Conway, P., Meehan, L. & Parham, D. (2015). Who benefits from productivity growth? – The labour income share in New Zealand. Working Paper 2015/1, NZ Productivity Commission.

Crawford, A., Harbridge, R. & Walsh, P. (2000). Unions and Union Membership in New Zealand: Annual Review for 1999. New Zealand Journal of Industrial Relations, 25(3), 291-302.

Dannin, E. (1997). Working Free: The Origins and Impact of New Zealand’s Employment Contracts Act. Auckland University Press.

Davidson, C., & Bray, M. (1994). Women and part time work in New Zealand: a contemporary insight. NZ Institute for Social Research and Development.

Deeks, J., Parker, J. & Ryan, R. (1994). Labour and Employment Relations in New Zealand. Longman Paul.

Du Plessis, R. (1993). Women, Politics and the State in New Zealand. In C. Rudd, C. & B. Roper (Eds.), The Political Economy of New Zealand (pp. 210-225). Oxford University Press.

Easton, D. (1997). The Economic Impact of the Employment Contracts Act. Californian Western International Law Journal, 28(1), 209-220.

Freeman, R. & Medoff, J. (1984). What Do Unions Do? Basic Books.

Gilson, C. & Wagar, T. (1997). The Impact of the New Zealand Employment Contracts Act on Individual Contracting: Measuring Organisational Performance. Californian Western International Law Journal, 28(1), 221-234.

Grills, W. (1994). The impact of the Employment Contracts Act on the labour law: Implications for unions. New Zealand Journal of Industrial Relations, 19(1), 85-101.

Harris, P. & Twiname, L. (1998). First Knights: an investigation of the New Zealand Business Roundtable. Howling At The Moon Publishing.

Haworth, N. & Hughes, S. (1995). Under Scrutiny: The ECA, the ILO and the NZCTU Complaint 1993-1995. New Zealand Journal of Industrial Relations, 20(2), 143-162.

Holt, J. (1986). Compulsory arbitration in New Zealand: the First Forty Years. Auckland University Press.

James, C. (1986). The quiet revolution: turbulence and transition in contemporary New Zealand. Allan & Unwin-Port Nicholson Press.

Kelsey, J. (1997). The New Zealand Experiment: A world model for structural adjustment? Auckland University Press.

MacDonald, F. (1994, October 8). You’re fired, I’m hired: Lawyers are big winners under the Employment Contracts Act. Listener, 28-30

McLaughlin, C. (2000). “Mutually Beneficial Agreements” in the Retail Sector? New Zealand Journal of Industrial Relations, 25(1), 1-17.

National Party. (1990). Election Manifesto.

New Zealand Department of Statistics. (1990). Labour Market Statistics. NZ Department of Statistics.

Peetz, D. (1998). Unions in a Contrary World. The Future of the Australian Trade Union Movement. Cambridge University Press.

Rasmussen. E. (2009). Employment Relations in New Zealand. Pearson.

Rasmussen, E., Bray, M. & Stewart, A. (2019). What is Distinctive about New Zealand’s Employment Relations Act 2000?’ Labour & Industry, 29(1), 52-73.

Rasmussen, E., & Greenwood, G. (2014). Conflict resolution in New Zealand. In W. K. Roche, P. Teague, & A. J. S. Colvin (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Conflict Management in Organizations (pp. 449-474). Oxford University Press.

Rasmussen, E. & Lamm, F. (2000). ‘New Zealand Employment Relations. In G. J Bamber, F. Park, C. Lee, P. K. Ross& K. Broadbent, K. (Eds.), Employment Relations in the Asia-Pacific: Changing Approaches (pp. 46-63). Allen & Unwin.

Spicer, B., Emanuel, D. & Powell, M. (1996). Transforming Government Enterprises: Managing radical organisational change in deregulated environments. Centre for Independent Studies, Melbourne.

Statistics New Zealand. 1994. Labour Market 1993. Statistics New Zealand.

Te Ara Encyclopaedia. (2018). Story: Strikes and labour disputes. https://teara.govt.nz/en/strikes-and-labour-disputes/page-10

Walsh, P. (1989). A Family Fight? Industrial Relations Reform under the Fourth Labour Government. In E. Easton (Ed.), The Making of Rogernomics (pp. 149-170). Auckland University Press.

Walsh, P. (1993). The State and Industrial Relations in New Zealand. In B. Roper & C. Rudd (Eds.), State and Economy in New Zealand (pp. 183-201). Oxford University Press.

Walsh, P. & Ryan, R. (1993). The Making of the Employment Contracts Act. In R. Harbridge (Ed.), Employment Contracts: New Zealand experiences (pp. 89-133). Victoria University Press.

Walsh, P. & Wetzel, K. (1993). Preparing for privatisation: Corporate strategy and industrial relations in New Zealand’s state owned enterprises. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 31(1), 57-74.

Wilson, R. (2000). The decade of non-compliance: The NZ government record of non-compliance with international labour standards 1990-98. New Zealand Journal of Industrial Relations, 25(1), 79-94.

- The distinction between the ‘primary and the secondary labour market’ is based on the Dual Labour Market Theory where the ‘secondary labour market’ is characterised by low status, low pay and often unsure employment, while the ‘primary labour market’ is associated with high status, high pay, and opportunities for upskilling, career development and promotion (see Rasmussen, 2009, pp. 429-431). ↵

- Later analyses of the same period do suggest, however, higher rates. For example, Conway et al. (2015) estimate that labour productivity growth averaged 2.9% in the 1990s, although they attribute a part of the late-1980s and early-1990s growth to labour-shedding associated with the economic reforms and low economic growth (Conway et al., 2015, p. 37). ↵