6

Erling Rasmussen; Gemma Piercy-Cameron; and Michael Fletcher

- To overview labour market changes and several embedded labour market and employment relations problems

- To identify how the Covid-19 pandemic has influenced labour market and employment relations trends

- To consider the main changes in vocational education and training

- To outline the main reasons for perennial low productivity growth and how this can be reversed in the future

- To present changes in employee participation and the limited role of mandatory participation structures

Introduction

New Zealand employment relations have experienced considerable changes over the last decades as shown in chapters 3, 4 and 5. This chapter deals with some of these changes and the associated trends and issues. It starts with an overview of labour market changes which highlights both stability and radical changes. Many of these changes were facilitated originally by the ECA 1991 and, since then, are linked to concerns about casualisation, low wages, gender and ethnicity issues, long working hours and ‘underemployment’. Similar concerns are also expressed in the ‘future of work’ debate though a sharp rise in casualisation, self-employment and short working hours is yet to occur.

While many economic and employment relations reforms were often premised on future gains the so-called neo-liberal ‘New Zealand Experiment’ never delivered the high wage, high skill, highly productive economy. Despite some public policy changes in the new millennium, there are still a prevalence of low wages, skill shortages and low productivity growth. There have been much research and many reports but there are still embedded labour market issues and a concerning lack of employment relations consensus regarding broadly based solutions. Will New Zealand continue to be reliant on importing overseas workers during economic upswings, sliding in international measures of productivity levels and living standards, and having weak information and consultation standards for employees?

The advent of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 prompted major short-term policy responses and may present new perspectives on the development of the New Zealand economy and labour market. The move towards a post-industrial society (Bell, 1974) was much slower in New Zealand until the opening of market access following the ‘New Zealand Experiment’ from 1984 onwards. However, even now primary industries are very important and being a producer of various form of food is properly regarded more positively following the Covid-19 pandemic. Although it is now seen as problematic that the decline of manufacturing and resultant reliance on overseas goods has created a certain level of vulnerability as has the strong growth in international tourism and hospitality. At the time of writing, it is unclear how much the temporary economic and labour market upheavals due to the pandemic will result in lasting changes or what the long-term outcomes will be.

Labour market issues

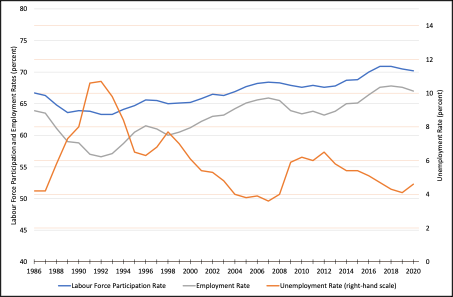

As can be seen from Figure 6.1 the New Zealand labour market has experienced strong employment growth and relatively low unemployment for most of the new millennium. The exception has been the Global Financial Crisis years, although even in those years, the unemployment rate was considerably below the OECD average. The expansion of employment and a rise in participation rate have been very strong and the participation rate has been one of highest amongst the OECD countries in recent years. These increases have coincided with an unprecedented influx of permanent migrants and of workers on temporary visas. Normally, net migration figures would oscillate between plus or minus 20,000 but net migration reached over 60,000 per annum under the 2014-2017 National-led government. By December 2020, the working age population (that is the usually resident population aged 15 years or over) stood at 4,094,000. This number comprised 2,748,000 people in employment, 141,000 who were unemployed, and 1,205,000 people who were not participating in the labour force (based on Statistics NZ’s Quarterly Series).

Figure 6.1 Labour force participation, employment and unemployment rates, 1986–2020

Source: Household Labour Force Survey, Statistic New Zealand

Covid-19 and the labour market

At time of writing in early 2022, New Zealand, like the rest of the world, is still influenced by the Covid-19 pandemic. New Zealand’s public health response has been highly successful, with just over 100 deaths recorded in March 2022. This is one of the lowest death rates per capita in the world. New Zealand’s economic and labour market response has also proven successful. The strategy of containing the virus domestically and maintaining strict border controls limited the impact on business activity, except in specific industries such as tourism and aviation. The Government’s large-scale wage subsidy scheme, although costly at over $14 billion by September 2021, was also effective in tiding most workers and employers over periods where many firms were forced to close either because of the Government-imposed lockdowns or for lack of custom. Other smaller schemes also helped with business continuity.

The uncertainty created by the Covid-19 pandemic has prompted wild predictions and significant fluctuations in labour market statistics. Early estimates that the effects of the pandemic might result in the unemployment rate rising to 8% or even higher have proven incorrect. The unemployment rate jumped from 3.9% in the June quarter 2020 to 5.1% in the September quarter but has since fallen back to 3.2% in late 2021. Similarly, the total number of people in employment, which had fallen by 42,000 in the first half of 2020 has returned to pre-Covid levels, although industries such as tourism and accommodation remain well below pre-Covid levels. Female employment fell more than male employment in the March and June 2020 quarters (negative 23,400 compared to negative 19,100) fuelling talk of a ‘shecession’; however, it also bounced back strongly. Still, a strong construction upswing and subdued hospitality and retail sectors have favoured male employment over female employment in 2021.

With the borders still mostly closed in 2021, sectors that have come to rely on temporary overseas labour, such as horticulture, tourism and hospitality, and some parts of agriculture, have been pressing government to allow more temporary workers to enter the country. To date, the Government’s main response has been to extend the existing temporary visas and provide a pathway to residency of those temporary workers already in New Zealand. There has also been targeted, restricted entry of some overseas workers, for example as part of the Recognised Seasonal Employer (RSE) Scheme.

Labour market and employment trends

Employment demands have been influenced by a certain level of catch-up of infrastructure shortfalls in previous decades but the Global Financial Crisis, the Christchurch earthquakes and repairing ‘leaky buildings’ have added to demand pressures in construction. The accommodation of unusually high net migration between 2013 and 2020 has also put pressure on the domestic construction industry. Besides construction, several sectors have experienced skills shortages and employer organisations have advocated fewer restrictions on permanent and temporary migrant workers. In particular, the tourism and hospitality sector had experienced very strong growth and, at least up until the border closure in March 2020, it had become our biggest income earner. It is too early to tell how tourism and hospitality will evolve post-Covid, whether it will revert to something similar to the pre-Covid period or whether both the number and ‘mix’ of tourists and employees will be different in future?

Many other OECD countries would envy the employment, unemployment and participation record of New Zealand over the last couple of decades. However, there are number of seriously embedded labour issues which have yet to be solved (OECD, 2019). As discussed below, the fundamental problem of low productivity growth has persisted, and this has been associated with an on-going decline in relative living standards and wealth. Economic growth has mainly been achieved by higher labour utilisation where more people have worked more (longer working hours) and, since the early 1990s, with the creation a relatively low paid workforce. Traditionally, skills shortages have been a companion of economic upswings, and this has also been the situation in most years in the new millennium (see next section). Thus, skill shortages have often been a major employer concern and have restrained economic growth, but this has yet to lead to fundamental shifts in pay levels or widespread business investment in vocational training and productivity-enhancing processes.

With the internationalisation of the New Zealand economy and with a strong growth in service sector jobs, concerns have been raised about a move towards a more flexible labour market with fewer full-time and less secure jobs (Groot et al., 2017). Whether it is called vulnerable work, employment insecurity, casualisation or precarious work these terms indicate expectations of a labour market which has less predictability in incomes, employment, and career progression. As shown in chapters 3 and 4, the New Zealand labour market has moved away from a historical high level of employment security since the comprehensive policy reforms of the 1980s and 1990s. The ‘future of work’ debate has also created widespread concerns about the risk of a labour market dominated by the ‘gig economy’ and a decline in permanent full-time employment (NZ Productivity Commission, 2019; Stewart & Stanford, 2017). That said, at least up until the Covid-19 pandemic, trends in official New Zealand statistics of various atypical employment types appear to have stabilised following the post-2008 Global Financial Crisis (see below).

When employment insecurity is measured the most commonly used statistical indicators are full-time versus part-time jobs, employees versus self-employed, and the extent of temporary and casual employment. As discussed below, there are many part-time jobs and a considerable number of self-employed, but the level of part-time jobs and self-employment have been relatively stable as a proportion of the workforce. These trends indicate that economic upswings have tended to generate as many full-time jobs as other forms of work. There have only been official statistics on the extent of temporary and casual employment since the 2008 Survey of Working Life. As can be seen in Table 6.2, this survey has now run another three times since 2008 and temporary and casual employment has been stable and fluctuated around or below 10% of the total employed population. Thus, the fragmented labour market of the ‘future of work’ has yet to arrive, according to the official statistics trends.

In the last three decades, part-time employees have constituted around 20% of all employees (according to the Household Labour Force Survey by Statistics New Zealand). There were 20.1% in December 1990, 22.5% in December 2000, 22.1% in December 2010 and 19.8% in December 2020. While the proportion of part-time employment has been fairly stable at around one-fifth of all employees, as the workforce has grown so, too, has the number of part-timers. As the number of employees increased from 1,535,000 in December 1990 to 2,831,000 in December 2021, part-time employees have risen from 308,535 in 1990 to 567,000 in December 2021. It is still predominantly women who are working part-time and that probably have some negative consequences in terms of career progression (see below).

Table 6.2 distinguishes between self-employed and employers by only including self-employed with no employees. As with part-time employment, Table 6.2 illustrates a remarkable stability in the proportion of self-employed in respect of the total employed population. While there can be advantages in being self-employed (see Chapter 1), there are also risks and uncertainties in terms of income volatility and work fluctuation where self-employed can experience a ‘famine or feast’ situation with lots or very few offers of work. Additionally, there are some sectors – for example, construction – where many jobs are designed to be self-employment and that can leave limited choice for workers. Finally, it is important to note that a significant part of the total employed population – nearly 20% – consist of employers and self-employed.

Thus, while we emphasise limited fluctuation in the general types of employment there are still types of employment where work and employment fluctuations are a constant part of work experiences. There are also many groups in the labour market with a tenuous relationship to job and career opportunities and these groups may grow proportionally in the coming years as indicated by the current debates about the ‘future of work’, the ‘gig economy’ and precarious work (see below).

| Employees | Employers | Self-employed, no employees |

|

| Dec 1990 | 80.2 | 7.8 | 10.5 |

| Dec 1995 | 79.1 | 7.0 | 12.7 |

| Dec. 2000 | 81.4 | 6.5 | 11.4 |

| Dec. 2005 | 83.7 | 4.5 | 10.6 |

| Dec. 2010 | 85.1 | 3.6 | 10.3 |

| Dec. 2015 | 80.2 | 6.5 | 12.4 |

| Dec. 2020 | 80.2 | 7.8 | 10.5 |

Source: Household Labour Force Survey, Statistic New Zealand

Note: totals do not sum to 100 because a small number of unpaid family workers has been excluded.

As shown in Table 6.3, there is so far no sign of a growth in temporary employment arrangements. Since the first official statistics in 2008, the total figures of temporary employment arrangements have been stable around 10% (with the 8.6% figure in 2020 probably being influenced by Covid-19 impacts). Likewise, the different forms of temporary employment relationships have also remained more or less stable over the same period. Generally, women are slightly more likely than men to be in temporary employment arrangements: 10.6% compared to 8.2%.

Compared to other OECD countries, New Zealand has an above average percentage of part-time employees, an about average proportion of self-employed and a slightly below average share of workers in temporary employment relationships. A key point, though, is that, across the OECD as a whole, there is no observable rise in casualised employment, at least as far as these very broad indicators are concerned. (Fletcher & Rasmussen, 2019: 36).

| Casual work | Fixed-term employment | Temping | Seasonal employment | TOTAL | |

| 2008 (Mar qtr) | 4.0 | 1.9 | 0.6 | 3.2 | 9.6 |

| 2012 (Dec qtr) | 4.1 | 2.6 | 0.7 | 3.5 | 10.9 |

| 2016 (Dec qtr) | 5.2 | 2.8 | 0.5 | 1.4 | 9.9 |

| 2020 (Dec qtr) | 4.9 | 2.3 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 8.6 |

Source: 2008 and 2012: Survey of Working Life; 2016 and 2020: Household Labour Force Survey, Statistics New Zealand.

While official statistics paint a fairly stable picture this doesn’t mean that employment insecurity and precarious work are not a considerable problem. Various studies suggest that income volatility can be problematic and that many people feel insecure about their current and future job situations (Moore, 2017; NZCTU, 2013). This is partly related to the exposure of the New Zealand economy to international changes as well as many jobs being seasonal or consumer-flow reliant. For example, the strong pre-Covid growth in tourism and hospitality has been associated with a high turnover of firms and jobs (Mooney et al., 2016; Williamson & Harris, 2019). There has also been considerable recent controversy over employment standards and working time (see below) as employers have tried to limit labour costs and match their staff levels to workflow. This included so-called ‘zero hours’ employment agreements without set working hours, which became common in some sectors such as hospitality until they were restricted by law changes in 2016 (Campbell, 2018).

Underemployment and what is called underutilisation are also significant labour market issues. The underemployed are part-time employees who would like more work while underutilisation is a broad measure of unemployment that includes the unemployed, the underemployed, those who would like work but are not actively seeking it, and those who are seeking work but are not able to begin work within four weeks. In December 2021, the total number of people classified as underutilised was 277,000 or 9.2% of the extended labour force. This indicates clearly that labour market inclusion is still a considerable problem, despite very low unemployment in 2021. Indeed, underutilisation has been over 10% in most years since 2007. A particular public policy focus has been the number of young people falling outside the wider labour market – young people (15-25 years of age) who are not in employment, education and training (NEET). Since the NEET statistics were developed in the early 2000s, there have been more than 10% in this category with a jump to 13%-14% during the Global Financial Crisis.

As in other OECD countries, there has been considerable attention paid to gender issues in New Zealand. The gender pay gap and the low number of female executive and board positions have been roundly criticised in the media and by researchers (Biswas et al., 2021; Tahir, 2016). Although there has been a decline in the gap between male and female earnings over time there is still a considerable gap of nearly 10%. While a number of factors will influence this difference, such as occupational patterns, job position, job tenure and number of hours worked, recent analyses have found that there is a significant gap left which is unexplained by such factors (Pacheco et al., 2019). Although female participation rates and female education achievements have increased in the new millennium there are still many traditional occupations – nursing, teaching, child-care and aged-care – which have predominantly female job holders. These sectors would benefit from the pay equity claims currently unfolding under the Labour Government as pay equity claims could create a similar round of pay rises as those implemented in the aged-care sector in 2017 (see Chapter 4).

Understandably, the gender discussion has been focused on gender imbalances and adverse outcomes for female workers. However, there are also considerable problems amongst working age men. Men tend to score, on average, high in suicides, imprisonment, and low in educational achievements. There are also many job categories where the proportion of men is very low. Interesting, the gender imbalance in educational achievements in favour of women has been bypassed with little media or public policy attention and with hardly any comprehensive attempts to improve the educational achievements of men (Rasmussen & Hannam, 2014). There has also been limited discussion of any links between the female prevalence in education jobs and the inability to address the lower level of educational achievements of boys and young men.

New Zealand has become a multi-cultural society, especially after the high levels of migration during 2012–2018. However, the long-standing labour market issues associated with Māori and Pacific peoples are still dominating official statistics. Māori and Pacific peoples are over-represented when it comes to unemployment (including long-term unemployment), young people not in employment, education and training (NEET), amongst people in seasonal employment and outside the labour force and importantly, amongst people in low paying jobs and occupations.

In the last three decades, the New Zealand population has been ‘greying’ and people over 60 years of age have become a significant proportion of the working age population. There appears to be two very different trends surrounding older workers. On one hand, there has been a considerable growth in employment participation amongst people over 60 years of age. This started by a lift in eligibility to receive superannuation to 65 years in 2001 but has been driven by other factors since. Besides being associated with older people feeling it financially necessary to keep on working, they may also feel that it is too early to retire. This can partly be associated with improved health and long lifespans. On the other hand, there are many stories about how older people have difficulty in securing another job when they have become redundant or want to re-enter the job market (Poulston, 2016). This is often associated with some form of age discrimination which is clearly unlawful but can also very difficult to detect and prevent.

Immigration and working hours

Following an upswing in migration after the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), immigration has been an important political and labour market issue. As discussed above, there has historically been an influx of migrants into New Zealand to cover skills shortages and this became pronounced during economic upswings. However, the debates were mainly about ‘brain drain’ and the ethnic mix and skill levels of migrants (Catley, 2001; Small, 2019), though sometimes with xenophobic overtones. The dramatic increase in permanent and temporary migrants in the 2013–2019 period prompted a political reaction and the political parties in the subsequent 2017 Labour-led government promised a reduction in migrant numbers during the 2017 election (Skilling & Molineaux, 2017). However, it lasted until the 2020 Covid-19 pandemic before a dramatic and immediate stop happened to migration. Now, the debates are mainly about when a post-pandemic change to migration can happen and what the new patterns of migration will look like. Will there be a major ‘reset’ of regulations surrounding migration and if so, what will this ‘reset’ entail?

Why has it been suggested that a ‘reset’ of migration levels is necessary? There appears to be little disagreement about the value of permanent, high skill migration to plug specific skills shortages and instead two key arguments in favour of a ‘reset’ have featured (see Fry & Wilson, 2020). First, the high level of temporary visa holders – estimated to be around 170,000 or 6% of the labour force in 2018 – distorted industry labour markets as some employers adjusted their business models to an availability of ‘imported, cheap labour’. This could have encouraged these employers to keep labour costs low and rely on temporary visa holders instead of local labour market employees. Second, it has been argued that “These policies reinforce a low-skill, low wage, low-capital status quo” (Fry & Wilson, 2020: i) and this has negative consequences for productivity growth. As discussed below, New Zealand’s productivity levels have languished compared to many other OECD countries and a ‘reset’ of migration policies could endeavour to enhance productivity growth through encouraging more investments in education and training and in new technology and working practices.

At the time of writing in early 2022, it is unclear whether there will be a significant ‘reset’ of migration policies and if so, how far this will go and what the consequences will be. So far, some employers have voiced strong concerns about the negative consequences for running their businesses. These are the employers in, for example, horticulture, hospitality, and retail sectors, who have benefited from a strong rise in temporary labour and there have been many media stories of fruit being unpicked and restaurants and retailers cutting opening hours during 2020–2021. Whether this has prompted employers to recruit from local labour markets and raise their wages is rather unclear though it appears to have happened in some parts of horticulture and hospitality. Thus, the theoretical and empirical arguments surrounding migration are likely to feature in the public debate for some time (Conway, 2021).

Working time patterns have been a key labour market issue for several decades. The traditional 40-hour week started to become less prevalent from the 1970s onwards and has covered less than a third of all jobs since the 1990s. The shift towards a post-industrial society and the influx of women in paid work were amongst the key factors driving this change. As mentioned above, a significant number of employees – predominantly women – work part-time. Part-time employment can often facilitate a better work-life balance, but it can also have detrimental career impacts, especially when it involves less than 20 hours a week. Also concerning is the embeddedness of long working hours in New Zealand working patterns. There is now more than one-third of the workforce that usually work more than 40 hours a week and around a quarter works more than 50 hours a week. As a result, Statistics New Zealand has started to record long working hours in 10-hour bands – for example, 60-70 hours a week – up to over 90 hours a week. Thus, the traditional images of ‘lazy’ New Zealanders and their focus on leisure pursuits have become less true and instead there are concerns that the long working hours have been associated with negative mental and physical well-being effects and with low productivity growth (New Zealand Productivity Commission, 2021; Wong et al., 2019).

Vocational education and training

In recent decades, increased education and vocational training have been seen a key solution in achieving economic success and social inclusion (OECD, 2018; Piercy & Cochrane, 2015). This is most often in reference to the elusive goal of establishing a high wage, high skill, highly productive economy (Rasmussen & Fletcher, 2018). However, there has often been disagreement on how to achieve a highly skilled, adaptable workforce to facilitate a high wage, highly productive economy. For example, debate continues over, whether it is the overall skill level or rather skill mismatches that is the problem in the New Zealand labour market.

As discussed in the next section, the recent strong public policy focus on improving productivity growth has yet to bear fruit. While vocational education and training is considered a core part of moving towards higher levels of productivity growth, the persistent disappointing productivity growth in New Zealand raises fundamental questions about education and vocational training systems, including investments in technological skills, and managerial abilities and approaches. In particular, what are the educational and training approaches and levers that will move New Zealand towards being a high wage, highly skilled and highly productive economy?

In the debates about the value of increased education and vocational training, it is often suggested that the future labour market will have fewer low-skilled jobs and that constant upskilling – ‘life-long learning’ – is necessary to avoid that shortages of skilled people constrain the productive capacity of the economy. While these suggestions appear intuitively plausible with frequent technological innovations, shifting consumer demands and synchronised economic upswing across OECD countries there are currently many service sector jobs with a limited range of technical skill requirements but with an emphasis on ‘soft’ skills and positive attitudes.

How to achieve a highly skilled, adaptable workforce is influenced by the nature of the national labour market, the kind of institutional support available to lift education and vocational training effort and approaches and attitudes of employers and workers. Comparative research has often lauded the well-established training cultures of Japan, Germany and Sweden with their emphasis on long-life learning and generic skills development. Interestingly, the stronger emphasis on firm-specific skills found in Anglo-American countries can also be considered a competitive advantage.

It is problematic that there appears to be ‘fads’ in what is currently recommended by international organisations – such as the OECD and the IMF – and there are considerable constraints in transferring positive lessons from one national labour market to other national labour markets (see Bamber et al., 2016). Besides embedded national institutions, there are also the influential attitudes and preferences of policy-makers, interest organisations, employers and workers. These historically developed institutions and attitudes present considerable barriers in transferring the vocational education and training approaches across countries.

Generally, education and vocational training efforts have often been insufficient in New Zealand and in particular, skill developments have had difficulty in keeping up with labour market demands during economic upswings. With a prevalence of small and medium sized businesses (SMEs) there has been a lack of resources and inclination to invest long-term in skill development and, associated with this, there has been a tendency to ‘poach’ staff from other organisations. Traditionally, the state played a crucial role since it was a major funder of polytechnic institutes and many large public sector organisations had significant apprenticeship and training schemes. While this wasn’t sufficient to meet labour market demands during the post-war economic upswing it did provide for a significant provision of skilled employees which were then often ‘poached’ by private sector employers. This changed dramatically when the so-called ‘New Zealand experiment’ started to unfold in the late 1980s and early 1990s as public sector reforms and growing unemployment curtailed training efforts (see Chapter 3).

Since the late 1980s, there has been considerable public debate over education and vocational training with dramatic public policy and institutional changes and with a regular re-occurrence of skill shortages and reliance of ‘importing labour’ (see below for more historical details). In the early 1990s, the National Government continued the neo-liberal ‘experiment’ by developing a completely new vocational training framework. During 1999–2008, the Labour-led governments continued this framework but introduced Modern Apprenticeships and increased public funding considerably. However, a strong economic upswing put vocational training efforts under considerable pressure until the 2008 Global Financial Crisis.

The 2008–2017 National-led Governments initially reduced investments in vocational education and training but the combination of the Christchurch rebuild after the 2010 earthquake, the ‘leaky building’ reconstructions and the return of economic growth meant that these governments battled skill shortages in their later years. Most recently, the post-2017 Labour-led Governments have announced a major overhaul of vocational education and training and besides implementing this major policy overhaul, the current government is also faced with a major re-balancing of the national economy after the fall-out from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Historical changes to vocational education and training policies

The 1992 Industry Training Act was part of the neo-liberal political ‘experiment’ and presented a radical different way of enhancing vocational training as well as introducing a completely new qualification framework. While there was widespread agreement on enhancing flexibility and portability of skill attainment, as well as meeting new training demands from the growing service sectors there was considerable disagreement about the Act’s reliance on market forces to provide sufficient and suitable training development (see Table 9.3 in Rasmussen, 2009: 252). The new Industry Training Organisations (ITOs) gave primacy to the employers’ role in highlighting and reacting to skill demands, government funding was initially very limited, and many employers had difficulty in navigating the new qualification framework. With subdued economic conditions and a radical new employment relations system many employers had little inclination to invest in training during the early to mid 1990s (see Chapter 3).

From the start of the Industry Training Act there were critical comments regarding its confusing growth of ITOs and qualifications as well as its ability to overcome traditional training weaknesses, including SMEs’ ability and willingness to invest in training. The new vocational education and training system also had to compensate for the downturn in training efforts prior and during the introduction of the new framework. By the mid-1990s, there were over 50 ITOs – equivalent to roughly 10 times the number of ITOs in Australia when measured in terms of employee numbers – and growing concerns about their efficiency and duplication of training efforts. Thus, the government had to deal with a fine-tuning of the new system as well as ramping up training efforts. In late 1990s, this led to an increase in public funding and constant pressure on ITOs to amalgamate and collaborate better with existing providers such as polytechnic institutes.

The 1999–2008 Labour-led governments came into power with promises of doing much better in vocational education and training. Prior to the 1999 general election, the Labour Party had promised a strong increase in public funding, a rise in training efforts and their coverage and in particular, the development of a Modern Apprenticeship scheme to increase the number of young people in apprenticeships. Interestingly, the Labour-led Governments kept most of the existing structures and tried instead to make the vocational training approach more efficient by facilitating ITO amalgamations, improve ITO-polytechnic institute collaborations and encourage employers to take on apprentices through the provision of education co-ordinators to manage apprenticeship paperwork.

With a strong economic upswing during 2002–2008 (see Chapter 4), there were rampant skill shortages, and the government quadrupled its vocation training funding during 1999–2008 (Collins, 2012). In line with its overall political philosophy the government also encouraged tripartite collaborations as exemplified by the 2008 Skill Strategy for New Zealand (Tertiary Education Commission, 2008). While official statistics showed a strong rise in university degrees, trainee numbers and vocational qualification completions this was insufficient and a kind of ‘catch-up’ was continuously being played in respect of labour market demands. Until the Global Financial Crisis in 2008, the new job vacancy surveys and statistics created by Department of Labour recorded unsatisfied demand in a wide range of occupations and jobs (Silverstone & Wall, 2008).

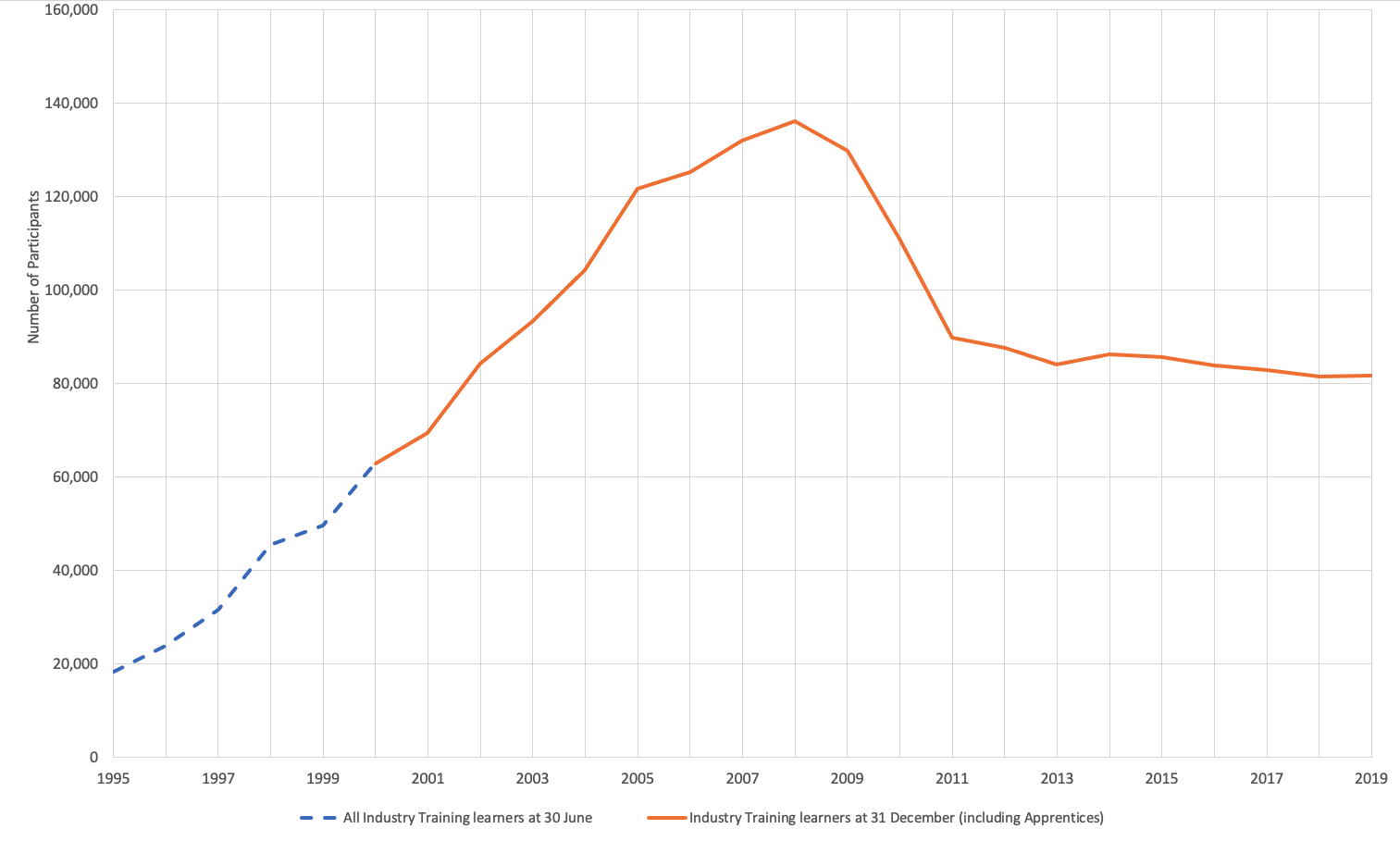

The 2008–2017 National-led governments were faced immediately with a major economic upheaval because of the Global Financial Crisis. As well, the Christchurch earthquakes and the ‘leaking buildings’ debacle created unprecedented demands in the construction industry. Interestingly, the government allowed vocational training to decline from 133,000 to 83,000 trainees during 2008–2011 (Collins, 2012). This decline is also recorded in Figure 6.2 and it created a considerable pent-up demand as construction projects took off and the economy improved. As a reaction, the government allowed considerable ‘import’ of workers and immigration soared to historically unprecedented levels with net migration peaking at over 60,000 in 2016–2018 (as discussed above). Extra funding was also allocated to vocational training providers and the government started to incentivise employers to take on apprentices. This resulted in training efforts and trainee numbers stabilising during 2015–2017.

Figure 6.2 Participants in industry training, 1995–2019

Source: Participation Industry Training 2020, Education Counts.

https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/statistics/vocational-education-and-training

Note: Counts from 2000 may not be comparable with previous years because of changes to reporting systems.

Like the previous Labour-led Governments, the National-led Governments’ training efforts were continuously playing ‘catch-up’, despite the unprecedented high level of net immigration during 2013–2017. During this period, a number of policy packages were announced. The first policy measure was the industry training review (2011–2012) that placed the performance of ITOs under scrutiny and led to operational reforms in 2013. The second key policy measure was the 2014 amendment to the Industry Training Act that removed the modern apprenticeship and trainee schemes and replaced them with New Zealand Apprenticeships (NZAs). Trades Academies were launched alongside NZAs’ scholarship scheme and were established in Secondary Schools, Polytechnics and Private Training Establishments (Piercy & Cochrane, 2015). Targeted reviews of qualifications were also undertaken by the New Zealand Qualifications Authority to reduce duplication and the Vocational Pathways initiative for career advice was established.

Another important policy package was Better Public Services. This initiative included the target to “Increase the proportion of 25 to 34-year-olds with advanced trade qualifications, diplomas and degrees (at level 4 or above) to 55%.” (New Zealand Government, 2012). Despite the overall inability to match demand for skilled labour, there were some improvements with fewer ITOs (falling from 38 in 2007 to 12 in 2017), a stronger focus on qualification completion rates, creating clearer career pathways for school leavers and establishing an annual occupational outlook to guide young people and other decision-makers.

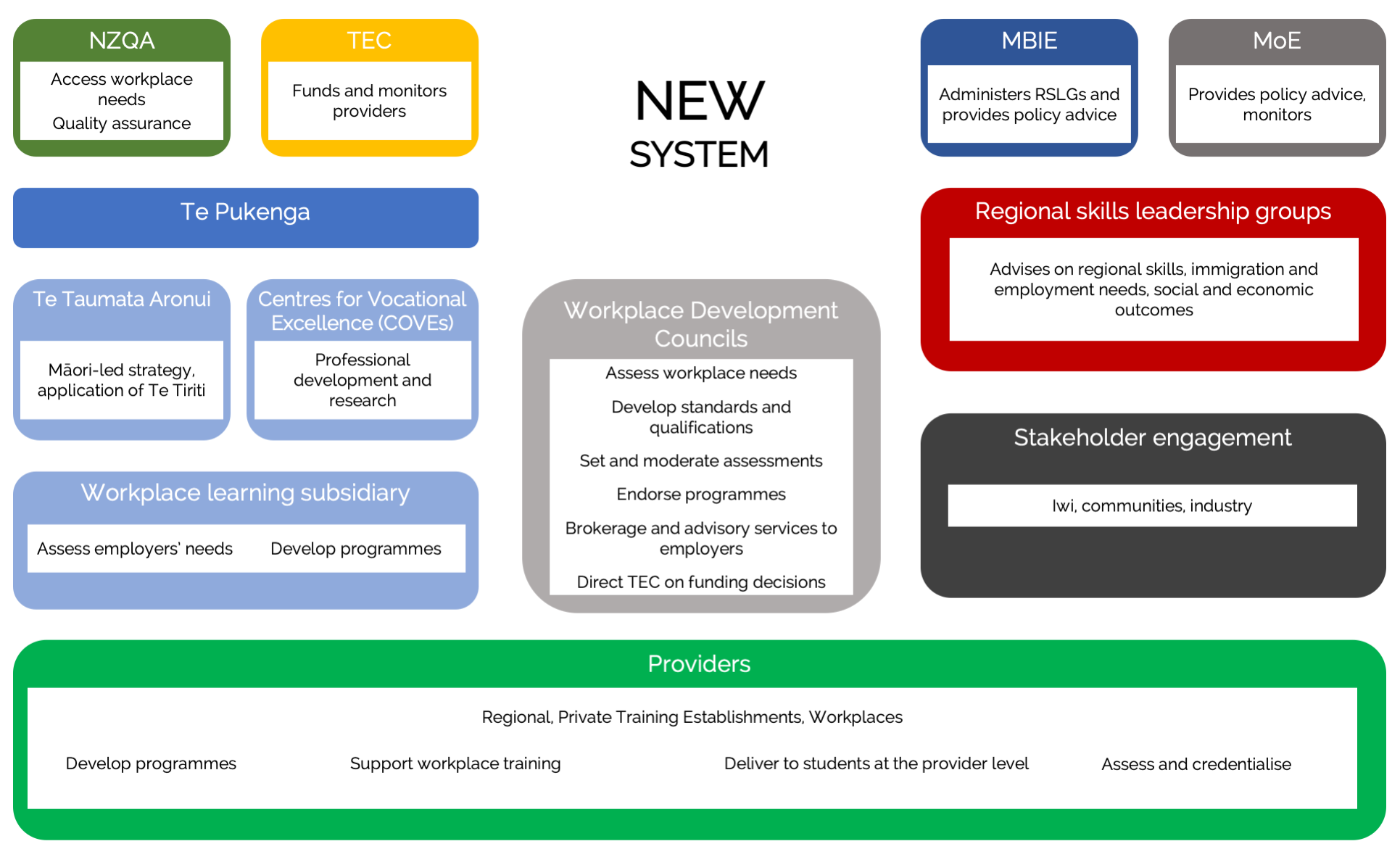

The 2017 Labour-led Government came into office with promises of significant improvements in the funding of education and vocational training. The Labour Party’s promise of three years of fee-free post-school study across a person’s lifetime became initially a one-year fee-free study right. The capital investments in schools were combined with a significant rise in funding as the government increased teachers’ salaries considerably, following several rounds of industrial disputes. Most importantly, the Government announced a radical overhaul of vocational education and training in 2019. The Reform of Vocational Education (RoVE) – based on the Education (Vocational Education and Training Reform) Amendment Act in April 2020 – was the biggest change since the Industry Training Act 1992. As detailed below, it involved new strategies, structures, funding mechanisms and education processes (see Figure 6.3).

Given the magnitude of the changes, the reform process was designed to give Polytechnics and Industry Training Organisations a three-year period to fully enact the reform process. The RoVE changes created Te Pukenga (NZ Institute of Skills and Technology) by merging 16 Polytechs (so-called Industry Training Providers – ITPs). This national organisation was responsible for supporting both workplace-based (on-job) training, and classroom-based (off-job) training. As such, some of the functions of ITOs will transition into this organisation. However, the merger process will not conclude until 2022 and, in the meantime, ITOs are currently operating as Transitional Industry Training Organisations.

Aspects of the ITO system will also contribute to six Workforce Development Councils that cover the vocational pathway sectors of:

- Manufacturing, Engineering and Logistics;

- Construction and Infrastructure;

- Creative, Cultural, Recreation and Technology;

- Health, Community and Social Services;

- Service Industries;

- Primary Industries.

The main function of the Workforce Development Councils is to develop national skills leadership plans to shape and inform the direction for workforce and qualification development for their respective industries. This has now been aligned with the government’s plans for industry partnership to develop transformational strategies.

Other organisations created by these reforms include Centres of Vocational Excellence, and Te Taumata Aronui (a group designed to ensure the reforms reflect the Government’s commitment to Māori Crown partnerships) that sits alongside the governance structure for Te Pukenga. The Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment is also responsible for regional skills leadership groups (RSLGs) that are governance bodies similar to Workforce Development Councils but their focus is on developing regional strategies for skills development. Overall, Te Pūkenga has 17 subsidiary organisations which provide vocational education and training throughout New Zealand. The subsidiaries are governed by Boards of Directors appointed by Te Pūkenga’s Council.

This is what the new system will look like:

Figure 6.3 Model of new vocation, education and training system

Source: Piercy-Cameron, 2022 (adapted from other available figures)

The radical reshaping of vocational education and training started just as the Covid-19 pandemic hit New Zealand. Skills development has been put forward as a solution to the unemployment and labour market dislocation caused by the pandemic. As such the reform process in relation to the WDCs and RSLGs has been accelerated. The government has also created a new policy initiative launched in July 2020 that fully funds sub-degree qualifications at levels 3-7 on the qualifications framework (Tertiary Education Commission, 2020). Uptake has been significant with more than 100,000 signing up for free vocational training courses and as well, in tandem with this change, a Southern Auckland initiative has focused on increased trades participation amongst Māori and Pasifika (for details, see Piercy & Rasmussen, 2022).

Despite these positive moves some of the involved organisations – especially some Polytechs and ITOs – have voiced their concerns over the potential fallouts for individual organisations and the overall ability of the new system to deliver quality education and training (Competenz, 2019). So far, the uptake of trades students appears to have addressed these potential fallouts, but it is happening in a situation where skills and labour shortages caused by border closure is putting the government under political pressure (see above). Interestingly, employers appear to be mainly positive about the changes and there has also been union support. Whether the lack of employer criticism has been overshadowed by the economic and industry disruption caused by the pandemic will probably first become clear when RoVE is fully implemented and the disruption of the pandemic is in the past.

Thus, at the time of writing, there is another major change happening in vocational education and training – on par with the 1990s changes – amidst economic rebuilding following the Covid-19 pandemic. While it has become a mantra that continuous skill developments should be an ingrained part of economic success and social inclusion there is a lack of clarity of how best to facilitate adequate skill development. This has clearly been the case in New Zealand where economic upswings and tight labour markets are associated with skill shortages and the ‘import’ of workers. Constantly, training efforts have lagged behind labour market demands and, besides belated investments in vocational education and training, various schemes have tried to alleviate labour shortfalls in many key industries, such as agriculture and horticulture, tourism and hospitality, construction and IT sectors.

The perennial problem of weak productivity growth

Productivity and rising productivity levels have become crucial measures of the relative success of national economies and their economic performance. As Nobel Prize Winner Paul Krugman has famously coined it: “Productivity isn’t everything, but, in the long run, it is almost everything. A country’s ability to improve its standard of living over time depends almost entirely on its ability to raise its output per worker.” (Krugman, 1994: 11). It has become, therefore, of considerable concern that New Zealand’s relative productivity growth has been dismal over many decades (Conway & Meehan, 2013; NZ Productivity Commission, 2016).

This has raised many questions and issues in respect of how to lift New Zealand’s productivity performance but there has been less success in providing sustainable improvements in actual productivity growth. Interestingly, the major employment relations framework changes in the last three to four decades have been driven partly by an attempt to lift productivity levels (see Chapters 3 & 4). Still, it has also been questioned recently whether legislative employment relations reforms in themselves can raise productivity performance significantly (Peetz, 2012; Rasmussen & Fletcher, 2018).

Discussions of productivity growth have been around for a long time and its basic conceptualisation – producing more value through using input resources better – is well-known economic territory (see Conway, 2016; NZ Productivity Commission, 2021). In basic terms, productivity drivers are: investments in physical and human capital, innovation and investments in research and development, competition pressures, superior workplace relationships and skill utilisation. Or as the NZ Productivity Commission (2021: 3) has formulated it, productivity can be lifted by “producing more with what we have (people, knowledge, skills, produced capital, and natural resources).”

However, productivity is also a tricky concept fraught with measurement problems and the literature will often use at least two different key measures: labour productivity and multifactor productivity. Labour productivity is normally understood as goods and services produced per worker or per hour worked and is measured as developments in output divided by labour input (Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita). Multifactor productivity is a broader concept that measures the amount of output produced by taking into account all the inputs used, including labour, capital, land and intermediate goods or raw materials. It therefore captures the efficiency with which all factors together are used to produce the outputs.

There are different views about the most successful ways for a country to achieve higher productivity growth. While the NZ Productivity Commission (2021: 38-42) points to the usual factors and especially highlights the role of innovation it is unclear exactly how it will happen that New Zealand “produces more with what we have”. There are stark differences between, for example, a neo-liberal approach of reduced state intervention, lower taxes, deregulation, and employer-driven flexibility and a social-democratic approach of considerable state intervention, high taxes, strong regulatory measures (often including support of collective bargaining), and comprehensive employee rights and protections.

| Measured sector |

Primary industries |

Goods producing industries |

Service industries |

Education & training |

Healthcare and social assistance |

Public admin & safety |

||

| 1997–2000 | LP | 2.9 | -0.4 | 3.2 | 3.3 | -1.3 | 5.6 | |

| MFP | 1.9 | -0.4 | 2 | 2.2 | -1.9 | 5.1 | ||

| 2000–2008 | LP | 1.3 | 2.1 | 0.6 | 1.7 | -1.5 | 0.8 | |

| MFP | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.9 | -1.7 | 0.5 | ||

| 2008–2018 | LP | 1 | 2 | 0.4 | 1.1 | -1.3 | -0.3 | |

| MFP | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0 | 0.7 | -1.6 | -0.3 | ||

| 1996–2018 | LP | 1.4 | 2.3 | 0.9 | 1.5 | -1.4 | 0.8 | |

| MFP | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 0.9 | -1.7 | 0.5 | ||

| Employment share | 1996 | 82.6 | 11.3 | 26 | 45.3 | 5.8 | 6.6 | 5 |

| 2018 | 77.9 | 6.9 | 22.3 | 48.7 | 7.3 | 9.1 | 5.6 |

Source: New Zealand Productivity Commission, 2019.

Note: LP = Labour Productivity; MFP = Multifactor Productivity.

As discussed in Chapters 3 and 4, the ECA 1991 was based on a very different understanding of achieving higher productivity growth than the ERA 2000. As well as these differences, there are a myriad of different combinations of public policy approaches and workplace practices which could be used to target higher economy-wide productivity growth rates, as well as continuous debates of whether regulatory measures are synchronised and supportive of each other (Haworth, 2010). This could include much stronger regulatory support for the role of unions and collective bargaining beyond the Employment Relations Act 2000, such as Fair Pay Agreements and union membership becomes an automatic option (see Harcourt et al., 2020; Kent, 2021).

As can be seen from Table 6.4, there has been downward trend overall in both labour productivity and multifactor productivity growth rates in the last three productivity cycles. The agriculture sector has shown the strongest growth, due in part to changes in land use and the shift to dairying. (Note that productivity as measured here does not capture negative environmental impacts such as water quality and greenhouse gas emissions.)

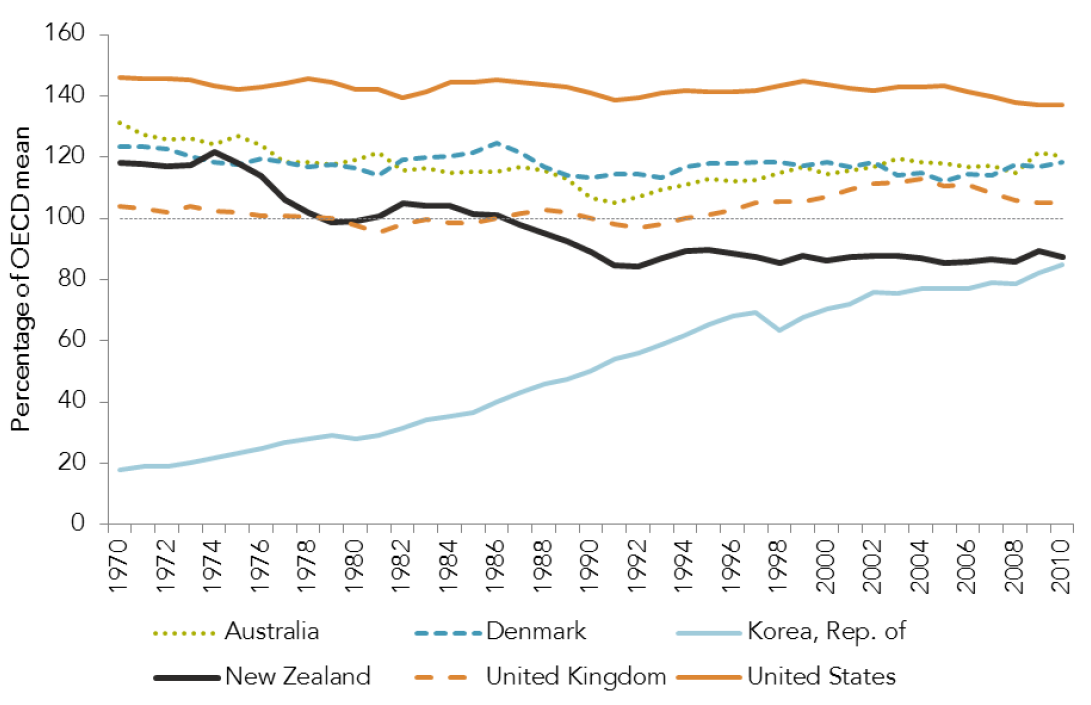

Figure 6.4 GDP per capita as a percentage of the OECD mean (US$ PPPs)

Source: Conway and Meehan, 2013, p.23

This downward trend is reflected in New Zealand’s declining relative productivity performance in respect to most other OECD countries (see Figure 6.4). This relative decline has been particularly important in respect of Australia where GDP per hour worked in New Zealand has dropped to less than 70% of that in Australia (after being on or above 100% in the 1960s). Or as formulated by Rasmussen and Fletcher (2018: 78): “though neither country can be pleased about their productivity growth it is clear that New Zealand’s productivity performance is at a different and much more concerning level.”

Thus, there is little disagreement that New Zealand needs to improve its productivity performance. The poor productivity growth has been described as a ‘paradox’ by international and domestic researchers based on their belief that the opening of the economy, wide-ranging deregulation, and decentralised workplace bargaining in the 1980s and 1990s would lift productivity growth levels (de Serres et al., 2014). However, it became clear in the second half of the 1990s that, despite some positive impact from job shedding and work intensification, there had not been a fundamental shift in productivity levels.

The disappointing productivity levels of the 1990s indicated that the public policy approach and reliance on more market-orientated solutions had been insufficient. Instead, it was argued that it would be necessary to pursue either stronger market-orientated interventions (as suggested by the Business Roundtable, see Kerr, 2008) or move in another direction with the state ensuring larger investments in infrastructure, training and development and new technology combined with more incentives for employers to enhance workplace productivity measures. The latter was clearly the opinion of the 1999–2008 Labour-led Governments (Wilson, 2004) which also shifted completely the view of collective bargaining and union activity from being perceived as barriers to being seen in a positive light (see Chapter 4). There were also specific initiatives such as the Workplace Productivity Group and the Workplace Partnership Centre. While these initiatives had some impact in the public sector and individual workplaces it had limited success in lifting national productivity performance in the 1999–2008 period (Haworth, 2010).

While the key tenets of the ERA were kept in place under the 2008–2017 National-led Governments there was a reversal towards an emphasis on employer-driven flexibility. There was also increased pressure on government funding prompted by the Global Financial Crises and the Christchurch earthquakes. The policy determined drive to secure a balanced budget meant that there was again a shortfall of investments in infrastructure, training and development and public sector services. This started to change in the National-led Government’s last years, including a significant lift in wages of age-care workers (see Chapter 4). A Productivity Commission was also established in 2012 and in the following years, it produced a string of reports on productivity issues, measures and potential barriers (for example, see Conway & Meehan, 2013; NZ Productivity Commission, 2019, 2021). However, the public policy influence of these reports appears to have been limited so far.

Thus, there have been significant changes in economic and labour market policies over the last three to four decades to lift labour market performance and productivity levels. In particular, the last two major legislative employment relations frameworks have been seeking to enhance productivity levels. As Table 6.4 and Figure 6.4 show, these reforms appear to have had limited impact and the search for stronger productivity growth – preferably stronger than most other OECD countries – is ongoing.

Following several decades of lacklustre productivity growth, there have been many different arguments about the reasons behind the inability to raise productivity levels, including the possible limited influence of legislative employment relations reforms (see Rasmussen & Fletcher, 2018). Interestingly, the influence of employment relations is less prevalent in the current debate as the most prevalent explanatory factors mentioned are: inadequate investments in infrastructure, new technology, research and workforce upskilling, ‘remoteness’ from key markets, insufficient managerial capabilities and approaches, short-termism and limited policy synergies, employment growth in low-productivity jobs, and overseas ownership or control of key economic activities (New Zealand Productivity Commission, 2019).

In short, there are many explanatory factors being raised. Interestingly, the current focus has moved away from the perceived negative influence of unions and collective bargaining and instead the focus is more on what employers and managers can do to increase productivity growth. Business strategies and behaviours are now being seen as problematic because many employers and sectors have become reliant on low paid workers, ‘poaching’, and ‘import of labour’. The current Labour Government seeks to encourage employers to move away from high labour utilisation and instead invest more in labour-saving, productivity-increasing technology and work practices (see above the current debate about immigration and ‘importing’ labour). While this has included more emphasis on stronger labour standards, higher statutory minima and increased vocational training efforts it is unclear whether this will overcome an inefficient reliance on ‘cheap labour’. Likewise, following the economic upheaval prompted by the Covid-19 pandemic it is debatable, as discussed above, whether this will provide a major economic and employment relations ‘reset’ or a continuation of the historical low productivity growth path.

Workplace change, partnerships and employee participation structures

There has been a long-term interest in employee participation and influence and this interest has increased with modern human resource management approaches where employee ‘buy-in’ or commitment is often seen as crucial for highly innovative and productive workplaces (Macky, 2018). However, there are at least three fundamental problems with this basic positive understanding of employee participation, influence and commitment.

First, it is often not specified in detail how this positive link to innovative and productive workplaces will actually take place as it assumes particular managerial and employee attitudes and behaviours (Caraker et al., 2016; Iqbal, 2019). Second, it is unclear how employee participation and influence is aligned with notion of managerial prerogative: does it assume a dilution of managerial prerogative and if so, how much dilution would such a rise in employee participation entail? Third, there are many different concepts applied – often indiscriminately – in the discussion of employee participation where it is unclear whether we are talking about: voluntary or legislative backed participation, direct or indirect (though a representative) participation, financial or non-financial participation (see Budd, 2014; Caraker et al., 2016; Rasmussen, 2009: 495-7).

There have been similar problems in the New Zealand debate and the concepts of employee participation, influence and commitment and their implementations are surrounded by controversy and a variety of understandings. While employers have been keen to promote more employment commitment of a voluntary nature there have also been several attempts to promote both union backed participation schemes and legislative backed participation structures. In the following, we will address these three different types of employee participation.

The managerial promotion of employee participation has often aligned with progressive human management approaches where employee involvement can have positive effects on organisational performance. There are, however, a number of assumptions associated with positive effects (see Ababneh & Macky, 2015) as well as demanding comprehensive and sustained management efforts (Newman & Freilekhman, 2020). Earlier New Zealand research has highlighted some positive management efforts to institute voluntary, low level participation mechanisms (see Boxall et al., 2007) though it is unclear whether these efforts are widespread currently. Still, recent literature has pointed to the importance of employee engagement, well-being and employee retention as underpinning organisational performance (Bailey et al., 2017; Edgar et al., 2018; Iqbal, 2019). This is particular the case in tight labour markets where the competition for skilled, talented and engaged employees often can be fierce and this has been the case in several industries during the post-2000 years in New Zealand.

Union backed schemes date as far back as the Second World War but there have mainly been two versions in recent decades: Workplace Reform in the 1990s and Workplace Partnerships in the 2000s. Workplace Reform started in the late 1980s, but it really gained traction when a tripartite organisation Workplace New Zealand was set up in 1991 (Perry et al., 1995). This organisation organised two large conferences in 1992 and 1996 and it supported and published information about workplace reform initiatives in New Zealand and overseas (Rasmussen, 2009: 479-482). While some major companies were involved in various workplace changes there was not broad-based support and some employers and unions were either ambivalent or against such collaborative efforts (Chong et al., 2001).

Workplace Partnerships were initially a public sector initiative promoted by the Public Sector Association (PSA). It received support through the Partnership Resource Centre which sponsored research and workplace interventions, including using nominated consultants (Rasmussen & Tedestedt, 2017). While the expected increase in collective bargaining did not occur under the ERA 2000 (see Chapter 4) there were several interesting workplace initiatives, especially in the public sector. However, Workplace Partnerships had difficulty in surviving the shift in government post-2008 and, besides a few organisations continuing their efforts, Workplace Partnerships started to disappear after the Global Financial Crisis. Whether this approach will be resurrected under the current Labour Government is still unclear.

There have been several attempts to institute legislative prescribed participation schemes and structures. Such schemes are different in nature since employers and managers have less say in their form and implementation. These schemes align with statutory employment minima but are different since small and medium size employers are often exempt. For example, the 1989 report of the Committee of Enquiry into Industrial Democracy proposed joint consultative committees in enterprises with 40 or more employees. However, the proposal sank without trace since it hardly featured in public policy debates of the time, it had limited union support, and employers preferred a voluntary approach (Deeks, 1990; Newman & Freilekhman, 2020; Rasmussen & Tedestedt, 2017).

The introduction of legislation backed occupational health and safety (OHS) committees in 2002 as part of the Health and Safety in Employment Amendment Act was a decisive step forward (see Chapter 5). These committees gave employee a legal right to elect health and safety representatives in organisations with 30 or more employees. This was further extended in the Health and Safety at Work Act 2015 where OHS committees were mandated in organisations with 20 or more employees. While there have been suggestions that OHS committees could be an integral part of more productive employment relationships (Lamm, 2010) there is little broadly based research evidence to support such claims and it is contradicted by New Zealand’s dismal health and safety record (Lilley et al., 2013; Pashorina-Nichols, 2016). It was acknowledged by Rasmussen and Tedestedt (2017: 184) that

…one can only wonder why the various governments and academic researchers have yet to put major efforts into evaluating employee participation in OHS. It is also interesting to note that some of the preliminary research findings show an uneven pattern across employers and their willingness to implement participatory process.

Overall, the three different approaches have disappointed in their extension and implementation though this is clearly an area where more research is needed. The voluntary schemes promoted by employers have seldom moved beyond informative and low level consultation. Across New Zealand organisations a variety of schemes has been tried but there is limited evidence available to evaluate the current dominant schemes and their impact. Interestingly, there appears to have been few financial participation schemes beyond traditional performance payment schemes and neither is there a New Zealand tradition for having tax inducements. With the decline in union strength, there have been few union-backed participation schemes and the Workplace Reform and Workplace Partnership attempts have had limited reach beyond particular firms and public sector organisations. While legislative mandated OHS committees have constituted something of a break-through in respect of legislative schemes their wider and specific workplace impacts have been unclear.

Conclusion

New Zealand employment relations have been through major changes but the longevity of the ERA 2000 has started to settle ‘things’ after the dramatic changes unleashed by the ECA 1991. The post-2000 reforms have made important changes to workplace employment relations – as described in Chapters 4 and 5 – but the main pillars of the ERA 2000 are still there and it is possible to establish key areas of change and disagreement.

This chapter is less about the ERA 2000 than its surrounding public policies and what employers, unions, employees and self-employed have agreed or accepted. These working standards are shifted by legislation about employment standards, pay equity and statutory minima as well as by societal norms, regulatory enforcement and media reports. It is an adjustment, however, that can often be rather slow and this is probably one of the reasons why the ‘low wage, low skill, low productivity’ and gender, ethnicity and age differences have become embedded issues. On that background, short-term adjustments are seldom about wholesale changes but rather about the direction (positive or negative) of changes.

Likewise, it is crucial to detect whether there have been shifts in the employment relations narrative and how it is envisaged that employment relations improvements can be brought about. The lingering of the neo-liberal, free-market approaches of the 1980s and 1990s can still be detected but there have been considerable adjustments to the thinking and narrative of key employment relations actors in the new millennium. In particular, stronger regulatory interventions have featured across a number of public policy areas as discussed above in respect of labour market inclusion (gender, ethnicity, age), vocational education and training, low wages, and OHS committees. It is also expected that there will be considerable change associated with how the economic and employment fall-outs of the 2020 and 2021 Covid-19 ‘lockdowns’ are and will be tackled.

References

Ababneh, O. & Macky, K. (2015). The meaning and measurement of employee engagement: A review of the literature. New Zealand Journal of Human Resource Management, 15(1), 1-35.

Anderson, P., & Warhurst, C. (2012). Lost in translation? Skills policy and the shift to skill ecosystems. In T. Dolphin and T. Nash (Eds.), Complex New World: Translating new economic theory into public policy (pp. 109-120). Institute for Public Policy Research.

Bailey, C., Madden, A., Alfes, K. & Fletcher, L. (2017). The meaning, antecedents and autcomes of employment engagement: A narrative synthesis. International Journal of Management Reviews, 19, 31-53.

Bamber, G. J., Lansbury R. D., Wailes, N., & Wright C. F. (2016). International and comparative employment relations: National regulation, global changes. (6th edition). Allen and Unwin.

Bell, D. 1974. The Coming of the Post-industrial Society. Heinemann.

Biswas, P.B., Roberts, H. & Stainback, K. (2021). Does women’s board representation affect non-managerial gender inequality? Human Resource Management, 60(4), 659-680. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.22066

Blackwood, K., Bentley, T., Green, N. & Tappin, D. (2018). Changing terrain: Flexible forms of working and their meaning for human resource management and employment relations. In Parker, J. & Baird, M. (Eds.), The Big Issues in Employment (pp. 51-72). Wolters Kluwer.

Boxall, P., Haynes, P. & Macky, K. (2007). Employee voice and voicelessness in New Zealand. In Freeman, R., Boxall, P. & Haynes, P. (Eds.), What workers say: Employee voice in the Anglo-American workplace (pp. 145-165). Cornell University Press.

Budd, J. (2014). The future of employee voice. In Wilkinson, A., Donaghey, J., Dundon, T. & Freeman, R. (Eds.), The handbook of research in employee voice (pp. 477-488). Edward Elgar.

Campbell, I. (2018). Zero-hour work arrangements in New Zealand: Union action, public controversy and two regulatory initiatives. In O’Sullivan, M., Lavelle, J., McMahon, J., Ryan, L., Murphy, C., Turner, T. & Gunnigle, P. (Eds.), Zero hours and on-call work in Anglo-Saxon countries (pp. 91-110). Springer.

Caraker, E., Jøregensen, H., Madsen, M.O. & Baadsgaard, K. (2016). Representation without co-determination? Economic and Industrial Democracy, 37(2), 269-295.

Catley, B. (2001). The New Zealand ‘brain drain’. People and Place, 9(3), 54-65.

Chong, K.P. Mealings, A. & Rasmussen, E. (2001). Giving voice to the employee: Employee perspectives of workplace reform in New Zealand. Paper, Department of Management and Employment Relations, University of Auckland.

Collins, S. (2012). Getting more bang out of our trade education buck. New Zealand Herald, 21 November 2012, pp. A18-A19.

Competenz. (2019). Vocational education reform ‘devastating’ for NZ industry. 19 March 2019. https://www.competenz.org.nz/news/vocational-education-reform-devastating-for-nz-industry/

Conway, P. (2016). Achieving New Zealand’s productivity potential. Research Paper 2016/1, New Zealand Productivity Commission.

Conway, P. (2021). Time for the migration conversation. Sunday Star-Times, 4 July 2021, p. 62.

Conway, P. & Meehan, L. (2013). Productivity by the numbers: The New Zealand experience. Research Paper 2013/1. New Zealand Productivity Commission.

Deeks, J.S. (1990). New tracks, old maps: continuity and change in New Zealand labour relations 1984-1990. New Zealand Journal of Industrial Relations, 15(2), 99-116.

de Serres, A., Yashiro, N. & Boulohol, H. (2014). An international perspective on the New Zealand productivity paradox. New Zealand Productivity Commission.

Edgar, F., Geare, A. & Zhang, J.A. (2018). Accentuating the positive: The mediating role of positive emotions in the HRM-contextual performance relationship. International Journal of Manpower, 39(7), 954-970.

Foster, B. & Rasmussen, E. (2017). The major parties: National’s and Labour’s employment relations policies. New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 42(2), 95-109.

Fry, J. & Wilson, P. (2021). Could do better. Migration and New Zealand’s frontier firms. Report commissioned by the NZ Productivity Commission, NZIER, September 2021.

Groot, S., van Ommen, C., Masters-Awatere, B., & Tassell-Matamua, N. (2017). Precarity: Uncertain, insecure and unequal lives in Aotearoa New Zealand. Massey University Press.

Harcourt, M., Gall, G., Wilson, M., Rubenstein, K. & Shang, S. (2020). Public support for a union defailt: Predicting factors and implications for public policy. Economic and Industrial Democracy, https://doi-org.ezproxy.aut.ac.nz/10.1177/0143831X20969811

Haworth, N. (2010). Economic transformation, productivity and employment relations in New Zealand 1999–2008. In Rasmussen, E. (ed.). Employment relationships: workers, unions and employers in New Zealand (pp. 149-167). Auckland University Press.

Iqbal, M. (2019). High-involvement work processes, trust and employee engagement: The mediating role of perceptions of organisational justice and politics. PhD Thesis, Auckland University of Technology.

Kent, A. (2021). New Zealand’s Fair Pay Agreements: A new direction in sectoral and occupational bargaining. Labour & Industry 31(3), 235-254. https://doi.org/10.1080/10301763.2021.1910899

Kerr, R. (2008). Closing gaps needs change of direction. NZ Herald, 28 April 2008, p. C2.

Krugman, P. (1994). The Age of Diminished Expectations. MIT Press.

Lamm, F. (2010). Participative and productive employment relations: the role of health and safety committees and worker representation. In Rasmussen, E. (ed.). Employment relationships: workers, unions and employers in New Zealand (pp. 168-184). Auckland University Press.

Lilley, R., Samaranayaka, A. & Weiss, H. (2013). International comparison of International Labour Organization published occupational fatal injury rates: How does New Zealand compare internationally? Commissioned report for the Independent Taskforce on Workplace Health and Safety. http://hstaskforce.govt.nz/working-papers.asp

Macky, K. (2018). Strategic people management – Where have we come from and where are we going? In Parker, J. & Baird, M. (Eds.), The Big Issues in Employment (pp. 203-223). Wolters Kluwer.

Mooney, S., Harris, C. & Ryan, I. (2016). Long hospitality career – A contradiction in terms? International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 28(11), 2589-2608.

Moore, T. (2017). Income volatility in New Zealand. Policy Quarterly, 13(4), 44-52.

Newman, A. & Freilekhman, I. (2020). A case for regulatory industrial democracy post Covid-19. New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 42(2), 70-76.

NZCTU. (2013). Under pressure: A detailed report into insecure work in New Zealand. NZ Council of Trades Unions.

New Zealand Government. (2012). Better public services results: Targets and public communication Cabinet paper. [CAB (12) 315]. https://www.publicservice.govt.nz/our-work/better-public-services/

New Zealand Productivity Commission. (2019). Technological change and the future of work. https://www.productivity.govt.nz/inquiries/technology-and-the-future-of-work/

New Zealand Productivity Commission. (2021). Productivity by the numbers: 2019. www.productivity.govt.nz/productivity-by-the-numbers/

New Zealand Productivity Commission. (2020). Research Publications. www.productivity.govt.nz/research

OECD. (2018). Opportunities for all: A framework for policy action on inclusive growth. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/

OECD. (2019). OECD economic survey of New Zealand. OECD Publishing.

Pacheco, G., Li, C. & Cochrane, B. (2019). An empirical examination of the gender pay gap in New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 44(1), 1-20.

Pashorina-Nichols, V. (2016). Occupational health and safety: Why and how should worker participation be enhanced in New Zealand? New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 41(2), 71-86.

Peetz, D. (2012). Does Industrial Relations Policy Affect Productivity? Australian Bulletin of Labour, 38(4), 268-292.

Perry, M., Davidson, C. & Hill, R. (1995). Reform at Work. Longman Paul.

Piercy, G., & Cochrane, B. (2015). The skills productivity disconnect: Aotearoa New Zealand industry training policy post-2008 election. New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 40(1), 53-69.

Piercy, G. & Rasmussen, E. (2022, February 8-10). Vocational education and training reforms before, under and beyond the Covid-19 pandemic. [Paper presentation]. New Zealand Political Studies Association conference, Auckland.

Poulston, J. (2016). Barriers to the employment of older hotel workers in New Zealand. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality and Tourism, 15(1), 45-68.

Rasmussen, E. & Fletcher, M. (2018). Employment relations reforms and New Zealand’s ‘productivity paradox’. Australian Journal of Labour Economics, 21(1), 75-92.

Rasmussen, E. & Hannam, B. (2014). Before and beyond the Great Financial Crisis: Men and education, labour market and well-being trends and issues in New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 38(3), 24-33.

Rasmussen, E. & Tedestedt, R. (2017). Waves of interest in employee participation in New Zealand. In Anderson, G., Geare, A., Rasmussen, E. & Wilson, M. (Eds.), Transforming workplace relations 1976-2016 (pp. 169-190). Victoria University Press.

Silverstone, B. & Wall, V. (2008). Job vacancy monitoring in New Zealand. [Paper presentation]. Labour, Employment and Work Conference, Wellington. https://ojs.victoria.ac.nz/LEW/article/view/1660

Skilling, P. & Molineaux, J. (2017). New Zealand’s minor parties and ER policy after 2017. New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 42(2), 110-128.

Small, Z. (2019, July 8). Statistics New Zealand no longer measuring ‘brain drain’ to Australia. Newshub. https://www.newshub.co.nz/home/politics/2019/03/statistics-new-zealand-no-longer-measuring-brain-drain-to-australia.html

Stewart, A. & Stanford, J. (2017). Regulating work in the gig economy: What are the options? Economic and Labour Relations Review, 28(3), 420-437.

Tahir, R. (2016). Does gender matter? Female representation on the corporate boards: The case study of New Zealand. International Journal of Management Development, 1(4): 307-320.

Tertiary Education Commission. (2020). Targeted training and apprenticeship fund. https://www.tec.govt.nz/funding/funding-and-performance/funding/fund-finder/targeted-training-and-apprenticeship-fund/

Williamson, D. & Harris, C. (2019). Talent management and unions. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(10), 3838-3854.

Wilson, M. (2004). The Employment Relations Act: a framework for a fairer way. In Rasmussen, E. (Ed.). Employment relationships: New Zealand’s Employment Relations Act (pp. 9-20). Auckland University Press.

Wong, K., Chan, A.H.S & Ngan, S.C. (2019). The effect of long working hours and overtime on occupational health: A meta-analysis of evidence from 1998 to 2018, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(12), 2102.