7 Doing the Work

Why Me? – Exploring Hesitancy

Many people worry about approaching Indigenization and Decolonization, (including me!). They may ask themselves: why do I have the right? Or tell themselves I won’t be able to ‘do it properly’.

These are normal thoughts and obstacles to address in order to move forward in a better way.

Activity: take a piece of paper and journal your hesitancies

- What are you hesitant about? Be as specific as possible

- Can you identify any underlying reasons for your hesitation, such as fear, uncertainty, lack of knowledge or experience, or past negative experiences?

- Outline some strategies to address your hesitancy (i.e. seeking out information, seeking support from others, or setting small achievable goals)

- What are some potential roadblocks that may arise and how can you plan ahead to overcome them?

Discussion: share this with your discussion group

As you progress in your journey of Indigenization & Decolonization the methods to overcome your personal hesitancy will become clear. In the meantime, here are four ideas to consider:

- Inaction will just perpetuate the status quo. Doing ‘nothing’ for the cause may feel like a neutral stance, but in actuality, it signals that the current setting is ‘okay’. Educating yourself is a fantastic actionable step.

- Everyone, including non-Indigenous people, have a part to play in Indigenization and Decolonization. If the leaves and branches of a tree are the ideas that flourish, then their roots are the invisible societal forces that support and ground them. Everyone carries the ability to support and make space for ideas and other ways of knowing.

- Mistakes are not just allowed; they are considered stepping stones, provided we move forward with genuine intent and a spirit of humility. Adopting an approach of honesty and modesty ensures we are navigating our journey in a good way.

- People need a safe space to explore difficult concepts such as Indigenization & Decolonization. A safe space is a physical and social environment in which individuals may explore their identities, histories, and cultures without external pressures, judgement, or discrimination.

How to Use this Resource

Embody storytelling to best connect with this resource.

We are all on our own journeys. We have our own pasts, perspectives, and ideas – understand and honour this! This is your personal story of Indigenization & Decolonization.

Just like any story, there are good times and bad times. You will make mistakes and there will be many uncomfortable moments. Seek this discomfort, and as you reflect, you will grow from it.

Keep an open mind to other perspectives as you listen, share, and grow together. Every experience is part of one’s story.

Journal, reflect, draw, discuss, and do anything else in order to deepen your learning and to honour your personal journey.

——-

This resource is just a start. Community, professionals, the land, Elders, and Knowledge Keepers are the ‘true’ teachers.

“Elders, Knowledge Keepers and Cultural Advisors are not self-taught individuals. They have been gifted with their respective teachings by other Elders or Knowledge Keepers, typically over years of mentorship and teaching,” (Queen’s University: Office of Indigenous Initiatives, 2020).

Discussion Prompt: What does it mean not to be self-taught? What is lost in self-teaching?

Progress Items:

- Join or form a discussion group on Indigenization and Decolonization in Education.How?

Ask friends and/or colleagues to work on the module together and meet-up weekly to discuss. - Immerse in the land and community. “Effective learning does not happen in a content vacuum,” (Anderson, 2008).How?

Attend events in the community, reach out to communities, contact organizations. - Develop a process for working with Elders, Knowledge Keepers, and Indigenous communities. Review the following guidelines and make your own version. Be aware that some practices are local and may not apply to Indigenous practices of the Land you work on.

- Brandon University. (2019). Guidelines for Respectful Engagement with Knowledge Keepers & Elders. https://www.brandonu.ca/indigenous/policies-guidelines/knowledge-keepers-and-elders/

- Antoine, A., Mason, R., Mason, R., Palahicky, S. & Rodriguez de France, C. (2018). Appendix F: Working with Elders in Pulling Together: A Guide for Curriculum Developers. Victoria, BC: BCcampus. https://opentextbc.ca/indigenizationcurriculumdevelopers/back-matter/appendix-f-working-with-elders/

- Ferland, N., Chen, A., Villagrán Becerra, G., & Guillou-Cormier, M. (2021). Working in Good Ways: Practitioner Workshop. Community Engaged Learning University of Manitoba. https://umanitoba.ca/sites/default/files/2021-05/practitioner-workbook.pdf

- Once you have done the work and can approach with understanding, respect, reciprocity, and humility, connect with Elders/Knowledge Keepers. Can you involve them in your course development and/or delivery?

Learn more:

Integration with Your Teaching Practice

As educational professionals, embracing Indigenization and Decolonization means adopting it into your personal pedagogy, as well as applying it as a tangible education practice.

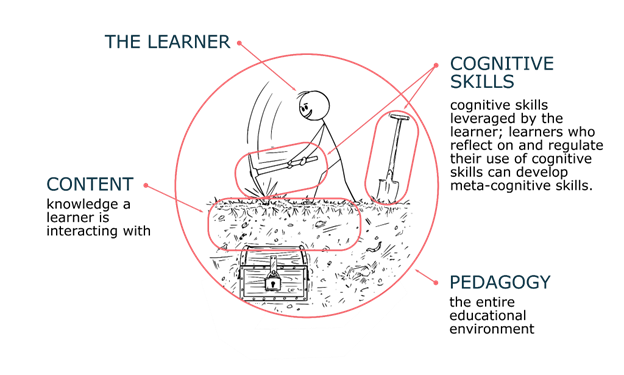

When developing and delivering a course, one potential Eurocentric lens to consider are three key aspects of education: content knowledge, meta-cognitive skills, and pedagogy.

Content knowledge refers to the factual, conceptual, and procedural knowledge that is being taught in the course. This type of knowledge can be directly taught through lectures, demonstrations, and other instructional methods.

Meta-cognitive skills involve thinking about one’s own thinking processes. These skills can only be indirectly taught through learning activities.

Pedagogy refers to the methods and strategies used by the teacher to facilitate learning. Teachers must carefully select and use a variety of instructional methods that are appropriate for the content being taught and the needs of their students.

Consider these three aspects of education when exploring this module and how Indigenization and Decolonization may integrate with your teaching practice. Look for opportunities beyond the content matter to Indigenize. We cannot just focus on content and not meta-cognitive skills and pedagogy.

Note: Content and meta-cognitive skills are simplified from the four knowledge types (Anderson et al., 2001)

Media Recommendations

Books

Talaga. T. (2017). Seven Fallen Feathers. House of Anansi.

“In 1966, twelve-year-old Chanie Wenjack froze to death on the railway tracks after running away from residential school. An inquest was called and four recommendations were made to prevent another tragedy. None of those recommendations were applied.

More than a quarter of a century later, from 2000 to 2011, seven Indigenous high school students died in Thunder Bay, Ontario. The seven were hundreds of miles away from their families, forced to leave home and live in a foreign and unwelcoming city. Five were found dead in the rivers surrounding Lake Superior, below a sacred Indigenous site. Jordan Wabasse, a gentle boy and star hockey player, disappeared into the minus twenty degrees Celsius night. The body of celebrated artist Norval Morrisseau’s grandson, Kyle, was pulled from a river, as was Curran Strang’s. Robyn Harper died in her boarding-house hallway and Paul Panacheese inexplicably collapsed on his kitchen floor. Reggie Bushie’s death finally prompted an inquest, seven years after the discovery of Jethro Anderson, the first boy whose body was found in the water.

Using a sweeping narrative focusing on the lives of the students, award-winning investigative journalist Tanya Talaga delves into the history of this small northern city that has come to manifest Canada’s long struggle with human rights violations against Indigenous communities.”

Kimmerer, R. W. (2013). Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants. Milkweed Edition.

“As a botanist, Robin Wall Kimmerer has been trained to ask questions of nature with the tools of science. As a member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, she embraces the notion that plants and animals are our oldest teachers. In Braiding Sweetgrass, Kimmerer brings these lenses of knowledge together to show that the awakening of a wider ecological consciousness requires the acknowledgment and celebration of our reciprocal relationship with the rest of the living world. For only when we can hear the languages of other beings are we capable of understanding the generosity of the earth, and learning to give our own gifts in return.”

Simpson, L, B. (2013). The Gift Is in the Making: Anishinaabeg Stories. HighWater Press.

“The Gift Is in the Making retells previously published Anishinaabeg stories, bringing to life Anishinaabeg values and teachings to a new generation. Readers are immersed in a world where all genders are respected, the tiniest being has influence in the world, and unconditional love binds families and communities to each other and to their homeland. Sprinkled with gentle humour and the Anishinaabe language, this collection speaks to children and adults alike, and reminds us of the timelessness of stories that touch the heart.

The Gift Is in the Making is the second title in The Debwe Series. Created in the spirit of the Anishinaabe concept debwe (to speak the truth), The Debwe Series is a collection of exceptional Aboriginal writings from across Canada.”

Van Horn, G., Kimmerer, R. W., & Hausdoerffer, J. (2021). Kinship: Belonging In A World Of Relations, Vol. 2 – Place. Center for Humans and Nature.

“We live in an astounding world of relations. We share these ties that bind with our fellow humans―and we share these relations with nonhuman beings as well. From the bacterium swimming in your belly to the trees exhaling the breath you breathe, this community of life is our kin―and, for many cultures around the world, being human is based upon this extended sense of kinship.

Kinship: Belonging in a World of Relations is a lively series that explores our deep interconnections with the living world. The five Kinship volumes―Planet, Place, Partners, Persons, Practice―offer essays, interviews, poetry, and stories of solidarity, highlighting the interdependence that exists between humans and nonhuman beings. More than 70 contributors―including Robin Wall Kimmerer, Richard Powers, David Abram, J. Drew Lanham, and Sharon Blackie―invite readers into cosmologies, narratives, and everyday interactions that embrace a more-than-human world as worthy of our response and responsibility.

Given the place-based circumstances of human evolution and culture, global consciousness may be too broad a scale of care. “Place,” Volume 2 of the Kinship series, addresses the bioregional, multispecies communities and landscapes within which we dwell. The essayists and poets in this volume take us around the world to a variety of distinctive places―from ethnobiologist Gary Paul Nabhan’s beloved and beleaguered sacred U.S.-Mexico borderlands, to Pacific islander and poet Craig Santos Perez’s ancestral shores, to writer Lisa María Madera’s “vibrant flow of kinship” in the equatorial Andes expressed in Pacha Mama’s constitutional rights in Ecuador. As Chippewa scholar-activist Melissa Nelson observes about kinning with place in her conversation with John Hausdoerffer: “Whether a desert mesa, a forested mountain, a windswept plain, or a crowded city―those places also participate in this serious play with raven cries, northern winds, car traffic, or coyote howls.” This volume reveals the ways in which playing in, tending to, and caring for place wraps us into a world of kinship.”

Joseph, B. (2018). 21 Things You May Not Know About the Indian Act: Helping Canadians Make Reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples a Reality. Indigenous Relations Press.

“Based on a viral article, 21 Things You May Not Know About the Indian Act is the essential guide to understanding the legal document and its repercussion on generations of Indigenous Peoples, written by a leading cultural sensitivity trainer.

Since its creation in 1876, the Indian Act has shaped, controlled, and constrained the lives and opportunities of Indigenous Peoples, and is at the root of many enduring stereotypes. Bob Joseph’s book comes at a key time in the reconciliation process, when awareness from both Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities is at a crescendo. Joseph explains how Indigenous Peoples can step out from under the Indian Act and return to self-government, self-determination, and self-reliance – and why doing so would result in a better country for every Canadian. He dissects the complex issues around truth and reconciliation, and clearly demonstrates why learning about the Indian Act’s cruel, enduring legacy is essential for the country to move toward true reconciliation.”

Linklater, R. (2014). Decolonizing Trauma Work: Indigenous Stories and Strategies. Fernwood Publishing.

“In Decolonizing Trauma Work, Renee Linklater explores healing and wellness in Indigenous communities on Turtle Island. Drawing on a decolonizing approach, which puts the “soul wound” of colonialism at the centre, Linklater engages ten Indigenous health care practitioners in a dialogue regarding Indigenous notions of wellness and wholistic health, critiques of psychiatry and psychiatric diagnoses, and Indigenous approaches to helping people through trauma, depression and experiences of parallel and multiple realities. Through stories and strategies that are grounded in Indigenous worldviews and embedded with cultural knowledge, Linklater offers purposeful and practical methods to help individuals and communities that have experienced trauma. Decolonizing Trauma Work, one of the first books of its kind, is a resource for education and training programs, health care practitioners, healing centres, clinical services and policy initiatives.”

Alfred, T. (1999). Peace, Power, Righteousness: An Indigenous Manifesto. Oxford University Press.

“This visionary manifesto, first published in 1999, has significantly improved our understanding of First Nations’ issues. Taiaiake Alfred calls for the indigenous peoples of North America to move beyond their 500-year history of pain, loss, and colonization, and move forward to the reality of self-determination. A leading Kanien’kehaka scholar and activist with intimate knowledge of both Native and Western traditions of thought, Alfred is uniquely placed to write this inspiring book. His account of the history and future of the indigenous peoples of North America is at once a bold and forceful critique of Indigenous leaders and politics, and a sensitive reflection on the traumas of colonization that shape our existence.”

Lowman, E. B. & Barker, A. J. (2015). Settler, Identity and Colonialism in 21st Century Canada. Fernwood Publishing.

“Through an engaging, and sometimes enraging, look at the relationships between Canada and Indigenous nations, Settler: Identity and Colonialism in 21st Century Canada explains what it means to be Settler and argues that accepting this identity is an important first step towards changing those relationships. Being Settler means understanding that Canada is deeply entangled in the violence of colonialism, and that this colonialism and pervasive violence continue to define contemporary political, economic and cultural life in Canada. It also means accepting our responsibility to struggle for change. Settler offers important ways forward — ways to decolonize relationships between Settler Canadians and Indigenous peoples — so that we can find new ways of being on the land, together.

This book presents a serious challenge. It offers no easy road, and lets no one off the hook. It will unsettle, but only to help Settler people find a pathway for transformative change, one that prepares us to imagine and move towards just and beneficial relationships with Indigenous nations. And this way forward may mean leaving much of what we know as Canada behind.”

Films

Rawal, S. (2020). Gather [Film]. Illumine Group. https://gather.film/

“Gather is an intimate portrait of the growing movement amongst Native Americans to reclaim their spiritual, political and cultural identities through food sovereignty, while battling the trauma of centuries of genocide.

Gather follows Nephi Craig, a chef from the White Mountain Apache Nation (Arizona), opening an indigenous café as a nutritional recovery clinic; Elsie Dubray, a young scientist from the Cheyenne River Sioux Nation (South Dakota), conducting landmark studies on bison; and the Ancestral Guard, a group of environmental activists from the Yurok Nation (Northern California), trying to save the Klamath river.”

Zegeye-Gebrehiwot, T., Carlson-Manathara, E., & Rowe, G. (2020). Stories of Decolonization. https://www.storiesofdecolonization.org

Stories of Decolonization is a multi-film interview-based documentary project that shares personal stories in order to explore accessible understandings of colonialism and its continued impact on those living on the lands now called Canada. It also explores notions and actions of decolonization.

Stories of Decolonization: Land Dispossession and Settlement is the first short film of the series, focusing specifically on stories of personal and ancestral connections to these lands. Come experience this film, build awareness, participate in dialogue, and take action!

Stories of Decolonization: (De)Colonial Relations is the second film in the series, is the project’s newest release. In this bilingual film (French and English, with subtitles), personal stories are woven into key insights regarding ongoing processes and structures of colonialism in Canada, and regarding the relationships and social locations carried by diverse peoples living on lands occupied by the Canadian state. With sensitivity to the intersectional oppressions experienced by diverse groups and the challenges these present, the film illuminates pathways forward toward solidarity, deeper relationality, and decolonization.

Obomsawin, A. (1992). Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance [Film]. National Film Board Of Canada. https://www.nfb.ca/film/kanehsatake_270_years_of_resistance/

“In July 1990, a dispute over a proposed golf course to be built on Kanien’kéhaka (Mohawk) lands in Oka, Quebec, set the stage for a historic confrontation that would grab international headlines and sear itself into the Canadian consciousness. Director Alanis Obomsawin—at times with a small crew, at times alone—spent 78 days behind Kanien’kéhaka lines filming the armed standoff between protestors, the Quebec police and the Canadian army. Released in 1993, this landmark documentary has been seen around the world, winning over a dozen international awards and making history at the Toronto International Film Festival, where it became the first documentary ever to win the Best Canadian Feature award. Jesse Wente, Director of Canada’s Indigenous Screen Office, has called it a “watershed film in the history of First Peoples cinema.”

Arnaquq-Baril, A. (2016). Angry Inuk [Film]. National Film Board of Canada.

In her award-winning documentary, director Alethea Arnaquq-Baril joins a new tech-savvy generation of Inuit as they campaign to challenge long-established perceptions of seal hunting. Armed with social media and their own sense of humour and justice, this group is bringing its own voice into the conversation and presenting themselves to the world as a modern people in dire need of a sustainable economy.

Tailfeathers, E., & Hepburn, K. (2019). The Body Remembers When the World Broke Open [Film]. Array Releasing; Experimental Forest Films.

When Áila encounters a young Indigenous woman, barefoot and crying in the rain, she soon discovers that this young woman, Rosie, has just escaped a violent assault at the hands of her boyfriend. Áila decides to bring Rosie home with her and over the course of the evening, the two navigate the aftermath of this traumatic event. Inspired by a very real and transformative moment in the co-director Elle-Máijá Tailfeather’s life, THE BODY REMEMBERS WHEN THE WORLD BROKE OPEN weaves an intricately complex, while at the same time very simple, story of a chance encounter between two Indigenous women with drastically different lived experience, navigating the aftermath of domestic abuse.

Hubbard, T. (2019). nîpawistamâsowin: We Will Stand Up [Film]. National Film Board of Canada.

On August 9, 2016, a young Cree man named Colten Boushie died from a gunshot to the back of his head after entering Gerald Stanley’s rural property with his friends. The jury’s subsequent acquittal of Stanley captured international attention, raising questions about racism embedded within Canada’s legal system and propelling Colten’s family to national and international stages in their pursuit of justice. Sensitively directed by Tasha Hubbard, nîpawistamâsowin: We Will Stand Up weaves a profound narrative encompassing the filmmaker’s own adoption, the stark history of colonialism on the Prairies, and a vision of a future where Indigenous children can live safely on their homelands.

Richardson, B. & Ianzelo, T. (1974). Cree Hunters of Mistassini [Film]. National Film Board Of Canada. https://www.nfb.ca/film/cree_hunters/

“An NFB crew filmed a group of three families, Cree hunters from Mistassini. Since times predating agriculture, this First Nations people have gone to the bush of the James Bay and Ungava Bay area to hunt. We see the building of the winter camp, the hunting and the rhythms of Cree family life.”

Dunn, W. (1968). The Ballad of Crowfoot [Film]. National Film Board Of Canada. https://www.nfb.ca/film/ballad_of_crowfoot/

“Released in 1968 and often referred to as Canada’s first music video, The Ballad of Crowfoot was directed by Willie Dunn, a Mi’kmaq/Scottish folk singer and activist who was part of the historic Indian Film Crew, the first all-Indigenous production unit at the NFB. The film is a powerful look at colonial betrayals, told through a striking montage of archival images and a ballad composed by Dunn himself about the legendary 19th-century Siksika (Blackfoot) chief who negotiated Treaty 7 on behalf of the Blackfoot Confederacy. The IFC’s inaugural release, Crowfoot was the first Indigenous-directed film to be made at the NFB.”

Mitchell, M. K. (1969). You Are on Indian Land [Film]. National Film Board Of Canada. https://www.nfb.ca/film/you_are_on_indian_land/

“Released in 1969, this short documentary was one of the most influential and widely distributed productions made by the Indian Film Crew (IFC), the first all-Indigenous unit at the NFB. It documents a 1969 protest by the Kanien’kéhaka (Mohawk) of Akwesasne, a territory that straddles the Canada–U.S. border. When Canadian authorities prohibited the duty-free cross-border passage of personal purchases—a right established by the Jay Treaty of 1794—Kanien’kéhaka protesters blocked the international bridge between Ontario and New York State. Director Michael Kanentakeron Mitchell later became Grand Chief of Akwesasne. The film was formally credited to him in 2017. You Are on Indian Land screened extensively across the continent, helping to mobilize a new wave of Indigenous activism. It notably was shown at the 1970 occupation of Alcatraz.”

References

Anderson, T. (2008). Towards a theory of online learning. In Anderson, T. & Elloumi, F. (Eds.), Theory and practice of online learning (pp. 45-74). Edmonton, AB: Athabasca University.

Anderson, L., Krathwohl, D., Airasian, P., Cruikshank, K., Mayer, R., Pintrich, P., Raths, J., & Wittrock, M. (2001). A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing: A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives Complete Edition.

Queen’s University: Office of Indigenous Initiatives. (2020). Elders, Knowledge Keepers, and Cultural Advisors. https://www.queensu.ca/indigenous/ways-knowing/elders-knowledge-keepers-and-cultural-advisors

Western University. (2018). Guide for Working with Indigenous Students: Interdisciplinary Development Initiative in Applied Indigenous Scholarship. https://teaching.uwo.ca/pdf/teaching/Guide-for-Working-with-Indigenous-Students.pdf