10 Build the Local Indigenous Voice

Build the Local Indigenous Voice

The Perfect Stranger

Lenape and Potawatami educational scholar Dr. Susan D. Dion, in this video, introduces what she considers the all-too-familiar position of the “perfect stranger” that many teachers take with respect to Indigenous students within their classroom. As this position is problematically characterized by not knowing as well not wanting to know about Indigeneity and, accordingly, not being implicated in relationships with Indigenous peoples, Susan Dion suggests a few pedagogical practices that work towards disrupting this problematic position.

Dion, S. (2013). Introducing and disrupting the “perfect stranger”. Vimeo. https://vimeo.com/59543958

Transcript

“Teachers would often say to me when they call me to ask me to come in and speak with their classes, they’d say, ‘oh, I don’t know anything about Aboriginal people. I didn’t grow up near reserve. I didn’t have any Aboriginal friends. I don’t know anything about Aboriginal people.’

And this refrain became quite familiar. Teachers quite often seem to want to tell me that they didn’t know anything and position themselves in this way of saying, I don’t know anything. And that has. You know, Aboriginal issues, that’s between Aboriginal people and the government, it doesn’t have anything to with me and there seemed to almost be this kind of urgency that I understand and appreciate, that this had nothing to do with them and this became such a familiar refrain from teachers that you had to do some thinking about this and thinking about what is this and why is there this desire to position the self as distant from Aboriginal people?

And I came to to recognize this positioning. and I named it the position of the perfect stranger. This position, a perfect stranger, allows teachers and actually all Canadians to be off the hook when it comes to thinking about Aboriginal issues. Thinking about people or the relationship between aboriginal and non Aboriginal people, there was a a desire to distance themselves from the issues and to say this has nothing to do with me.

I find it a very useful term to be able to to talk about that desire to be off the hook. If teachers have this desire to be the perfect stranger, then how do I disrupt that positioning? How do I engage teachers in learning experiences? That will allow them to see the ways in which they are in fact in relationship with Aboriginal people approach that I have is really asking teachers to investigate the biography of their relationship, and I’ve come to understand the significance of this, and in doing and accomplishing decolonizing education to have teachers think about what do I know about Aboriginal people and importantly, what informs my knowing? Where did this knowledge that I have about Aboriginal people come from? So in many of my workshops and courses and talks with teachers, I start with an images exercise and I lay out on a table.

Just a range of images of Aboriginal people and then I invite participants to choose an image and write about what’s their connection to that image and what this exercise does is it allows people to just begin to think about what’s my connection with Aboriginal people.

You know, such a range of discourses that circulate that inform Canadians understanding of Aboriginal people and it really just takes a few minutes for people to look at these images and choose something and write about it. The images exercise is a way to start involving teachers in thinking about the biography of their relationship.

So we start with that those images and people start to talk to each other about the stories that they’ve heard. You know, maybe they remember passing a sign on their way to the cottage. You know, this is Mohawk territory or this is an Indian reserve and then they start to think about what do they know, what do they not know and what informs.

You know, and so that’s the the project of the investigating, the biography of relationship that is a way to engage teachers in thinking about and beginning to question well, if I’m not a perfect stranger, then what do I know? And what’s the significance of what I know and what do I need to know.”

Activity: Reflect individually in a journal and/or engage in a group discussion on the following questions:

- Can you recognize aspects of the “perfect stranger” persona within yourself or among your friends, family, or colleagues? How does this mindset emerge in your interactions with or perceptions of Indigenous peoples?

- What do you understand about Indigenous people, and what shapes this understanding? Where did this knowledge about Indigenous peoples come from?

- What does it mean to not be a “perfect stranger”?

References

Dion, S. (2013). Introducing and disrupting the “perfect stranger”. Vimeo. https://vimeo.com/59543958

Combat Racism

It is absolutely ridiculous that in this day and age, we must still fight to overcome racism. Racism can significantly impact students, faculty, and our society at large. When people are exposed to racist attitudes it can influence how people perceive themselves and others.

“Indigenous peoples have been on these lands for time immemorial, thousands of years before Canada became a nation. Indigenous peoples are NOT Indigenous or Native to Canada.

Many Indigenous peoples DO NOT consider themselves Canadians. They are part of their own sovereign nations and do not consider themselves part of one that has actively worked to assimilate their people.

Stop saying “our”. Indigenous people do not belong to Canada. Canada is bound to Indigenous peoples through treaties that were made by early representatives of the Crown. By saying “our” or “Canada’s Indigenous peoples”, you are reinforcing a false narrative that is paternalistic. This narrative is one that was created by the Canadian state and is false.”

– Queen’s University (2023)

People who experience racism may feel isolated and unwelcome in their community, which can lead to feelings of anxiety, depression, and low self-esteem (Rees, 2020).

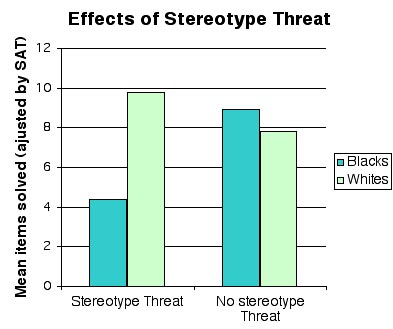

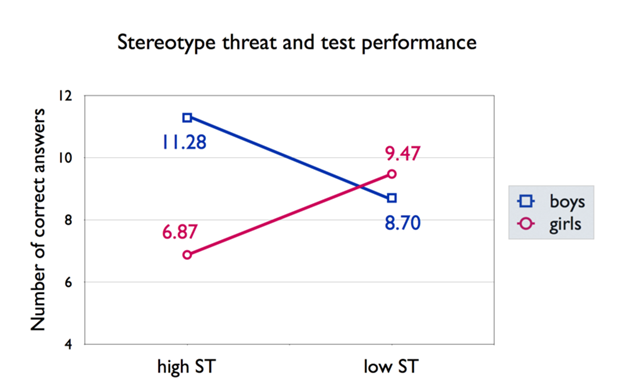

Racism can also have a large impact on students’ performance. Students who experience racism may unconsciously divert attention away from their studies and onto their sense of belonging and self-worth (Steele, 2010). Additionally, racist attitudes and beliefs can affect teachers’ and communities’ expectations of students, leading to unfair treatment and a lack of support for students who are seen as “different.”

Not all instances of racism are obvious or explicit. People may make assumptions based on stereotypes or exhibit prejudice without realizing it (Steele, 2010). Racism can be conveyed through contingency cues, such as choice of words, choice of examples or authors, or through underrepresentation (Steele, 2010). Microaggressions, another form of racism, are brief and often unintended statements or actions that can have a negative impact on marginalized groups (Sue et al., 2007). We all hold implicit biases and exploring these biases can help us understand how they affect our thoughts and actions (Ungvarsky, 2020).

It is crucial for educators as well as the community to be aware of the power of racism and its impact on students. By creating a safe and inclusive environment, we can help students feel valued and respected, regardless of their race or ethnicity.

Activity: Test the implicit biases you may hold: https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/takeatest.html

These tests are developed by Project Implicit, a non-profit organization founded by multiple researchers. They function based on word association – it measures how quickly you associate the given words to a specific group which may give a glimpse into your unconscious biases.

It’s important to note that these reflect one’s implicit bias or automatic thoughts. We do not all act nor accept our first thoughts and most importantly, our implicit biases do not define us, especially if we reflect and challenge them where appropriate.

Adrian Granchelli, Grey&Ivy Collaborator:

“I like to believe I am not very biased. I took the ”Gender – Science Implicit Association Test” and scored terribly! I had an 80% bias in favour of a link between liberal arts to females and between science to males. These results were eye-opening and honestly, a bit hard to stomach.”

Learn more:

- Loppie, C. & Barker, A. (2016). Racism and Privilege in the Everyday. Learning with Syeyutses. Nanaimo Ladysmith Public School & UBC Press. https://www.icscollaborative.com/webinars/racism-and-privilege-in-the-everyday

- McDermott, D. & Sjoberg, D. (2017). Deconstructing’ Racism: Strategies for Individual and Organizational Change. Learning with Syeyutses. Nanaimo Ladysmith Public School & UBC Press. https://www.icscollaborative.com/webinars/deconstructing-racism-strategies-for-organizational-change

References

Queen’s University. (2023). Terminology Guide. Office of Indigenous Iniitiatives. Queen’s University. https://www.queensu.ca/indigenous/ways-knowing/terminology-guide

Rees, M. (2020). What is the link between racism and mental health? Medical News Today. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/racism-and-mental-health

Sue, D. W., Capodilupo, C. M., Torino, G. C., Bucceri, J. M., Holder, A. M. B., Nadal, K. L., & Esquilin, M. (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist, 62(4), 271-286.

Steele, C. (2010). Whistling Vivaldi. W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. New York.

Ungvarsky, K. (2020). Implicit Bias. Salem Press Encyclopedia, Research Starters. EBSCO Information Services, Inc.

Creating a Safe Space

Marginalized individuals can face numerous challenges, from discrimination and harassment to a lack of representation and resources. It is crucial that Indigenous peoples feel welcome and included. There is no room for racism, intolerance, discrimination, hostility, or bigotry in a safe space.

Saving space means taking deliberate steps to create safe and accessible physical and social environments for individuals as well as for cultures. By doing so, we can help foster a sense of belonging, build community, and provide support and resources that may not be available elsewhere.

“We have achieved cultural safety when First Nations tell us we have.”

(First Nations Health Authority, 2017b)

Whether it’s creating safe spaces for marginalized groups, providing opportunities for representation and participation in decision-making processes, or challenging dominant narratives and power structures that perpetuate marginalization, saving space is a critical component of creating a more equitable and just society. It is important to recognize the significance of saving space and actively work to promote inclusivity and accessibility in all areas of our lives. By doing so, we can help ensure that everyone has the opportunity to thrive and succeed, regardless of their identities or backgrounds.

Cultural safety is an outcome based on respectful engagement that recognizes and strives to address power imbalances … It results in an environment free of racism and discrimination, where people feel safe when receiving health care.

Cultural humility is a process of self-reflection to understand personal and systemic biases and to develop and maintain respectful processes and relationships based on mutual trust. Cultural humility involves humbly acknowledging oneself as a learner when it comes to understanding another’s experience.

(First Nations Health Authority, 2017a)

It is everyone’s responsibility to create a safe space and to stand up to those who act otherwise. To be best equipped, seek out local training; the “The [Ontario Federation of Indigenous Friendship Centres]’s Indigenous Cultural Competency Training (ICCT) program enables participants to build skills, knowledge, attitudes and values essential to fostering positive and productive relationships with Indigenous people” (Ontario Federation of Indigenous Friendship Centres, 2020).

Learn more:

- First Nations Health Authority. (2021). Cultural Safety and Humility. https://www.fnha.ca/wellness/wellness-and-the-first-nations-health-authority/cultural-safety-and-humility

- Cote-Meek, S. & Patel, L. (2018). Cultural Safety in the Classroom: Addressing Anti-Indigenous Racism in Education Settings. Learning with Syeyutses. Nanaimo Ladysmith Public School & UBC Press. https://www.icscollaborative.com/webinars/cultural-safety-in-the-classroom-addressing-anti-indigenous-racism-in-education-settings

- Sinclair, M. & Rogers, S. (2017). Racism, Reconciliation, and Indigenous Cultural Safety. Learning with Syeyutses. Nanaimo Ladysmith Public School & UBC Press. https://www.icscollaborative.com/webinars/racism-reconciliation-and-indigenous-cultural-safety

Cultural Training:

- San’yas Anti-Racism Indigenous Cultural Safety Training Program: https://sanyas.ca/home

- Indigenous Cultural Competency Training (Ontario): https://ofifc.org/training-learning/indigenous-cultural-competency-training-icct/

- First Peoples Group Training (Online remote; Ontario): https://firstpeoplesgroup.com/training/

- Indigenous Canada (Online) https://www.ualberta.ca/admissions-programs/online-courses/indigenous-canada/index.html

References

Bradd, S. (2016). Leading a Framework for Cultural Safety & Humility. First Nations Health Authority. https://www.fnha.ca/PublishingImages/wellness/cultural-humility/FNHA-Cultural-Safety-and-Humility-Graphic-Sam-Bradd.jpg

First Nations Health Authority. (2017a). Creating a Climate for Change. https://www.fnha.ca/Documents/FNHA-Creating-a-Climate-For-Change-Cultural-Humility-Resource-Booklet.pdf

First Nations Health Authority. (2017b). FNHA’s Policy Statement on Cultural Safety and Humility. https://www.fnha.ca/Documents/FNHA-Policy-Statement-Cultural-Safety-and-Humility.pdf

Ontario Federation of Indigenous Friendship Centres. (2020). Indigenous Cultural Competency Training (ICCT). https://ofifc.org/training-learning/indigenous-cultural-competency-training-icct/

Connect with the Indigenous Community

In every interaction, we bring more than just our present selves. Our past experiences, knowledge, and perspectives also take part in shaping every exchange. When approaching any relationship, especially those with Indigenous Communities, we must approach with the 4R’s – Respect, Relevance, Reciprocity, Responsibility.

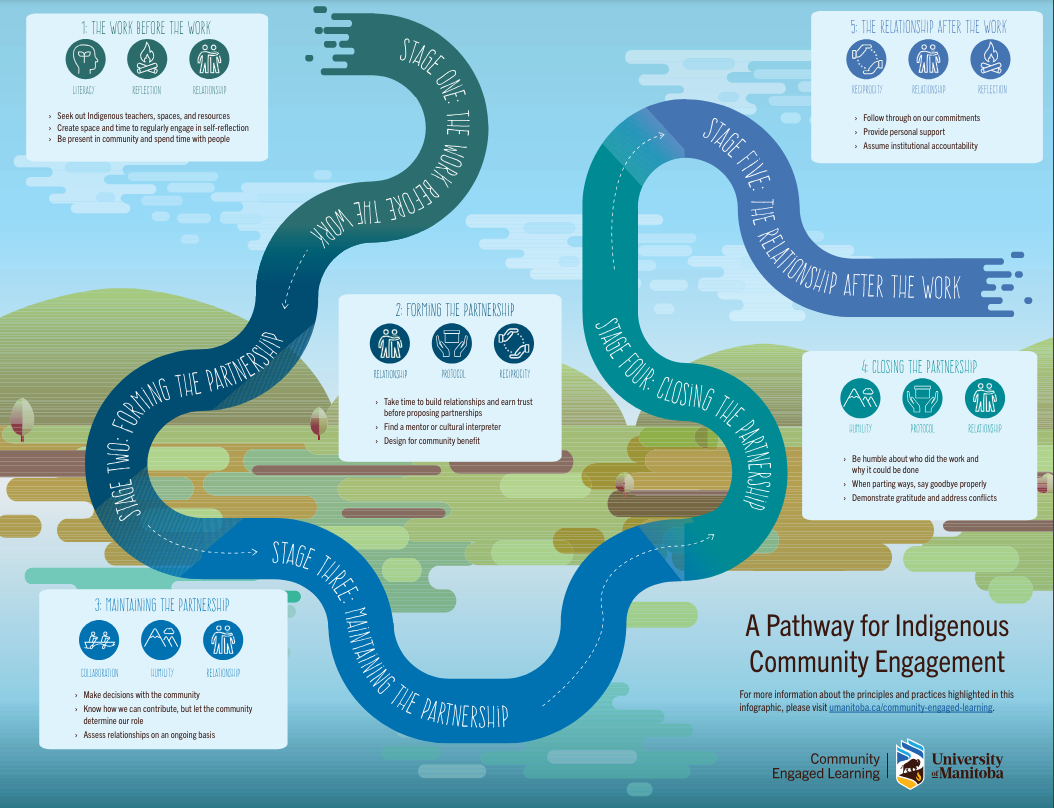

The University of Manitoba (2021) outlines a five-step plan to engage with Indigenous communities.

- The Work Before the Work

- Seek out Indigenous teachers, spaces, and resources

- Create space and time to regularly engage in self-reflection

- Be present in community and spend time with people

- Forming the Partnership

- Take time to build relationships and earn trust before proposing partnerships

- Find a mentor or cultural interpreter

- Design for community benefit

- Maintaining the Partnership

- Make decisions with the community

- Know how we can contribute, but let the community determine our role

- Assess relationships on an ongoing basis

- Closing the Partnership

- Be humble about who did the work and why it could be done

- When parting ways, say goodbye properly

- Demonstrate gratitude and address conflicts

- The Relationship After the Work

- Follow through on our commitments

- Provide personal support

- Assume institutional accountability

Activity

Reflect upon your and your organizations readiness, ability, purpose, and values to engaging with Indigenous Communities through this tool developed by Communities Choose Well (2023).

Values:

- What are my values?

- Do my values match, align or complement the values of the potential Indigenous community partner?

Capacity:

- Do I have the capacity to participate in genuine relationship building outside of working hours on an ongoing basis?

- Do I have the capacity and interest in participating in the practice of “making relatives”?

Resource Sharing:

- Am I able and prepared to provide resources (including funding) to the partner if they are better positioned to use it?

- Am I prepared to support activities/ initiatives that do not directly produce or contribute to my or my organization’s outputs or deliverables? (e.x., participate/ host/ fund a community event that meets a community need but does not contribute to your deliverables.

Allyship & Sharing Power:

- Am I willing to participate in allyship?

- Am I willing to use your power to have difficult conversations to advocate for your Indigenous partners? (i.e. Am I prepared to relocate an event if a space will not allow for important protocols like smudging?)

All of the questions as well as reflections can be found here:

Communities Choose Well. (2023). How to Effectively Engage with Indigenous Communities.

References

University of Manitoba. (2021). A Pathway For Indigenous Community Engagement. https://umanitoba.ca/sites/default/files/2021-05/a-pathway-for-indigenous-community-engagement-infographic.pdf

How-to Support Indigenous Students

Indigenous students face numerous barriers and challenges that can make their educational journey complicated and difficult. In order to create an inclusive and supportive learning environment, it’s essential to adopt a holistic approach that addresses their unique needs and experiences. By doing so, we can help Indigenous students feel welcomed, valued, and empowered to achieve their academic goals.

Western University (2018) identified and organized the barrier Indigenous students may face into six themes:

- Historical & Ongoing Threat of Assimilation

- Access-to-Education Barriers

- Financial Barriers

- Geographics Barriers

- Social, Cultural & Political Barriers

- Contextual Barriers

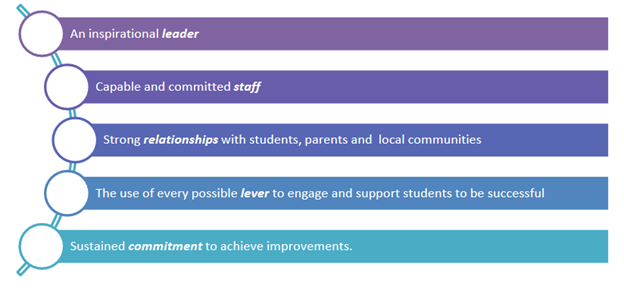

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2017), have reported that students feel support when the people at their schools:

- “Care about them and who they are as Indigenous people;”

- “Expect them to succeed in education; and,”

- “Help them to learn about their cultures, histories and languages” (p. 2).

Fuller et al. (2021) share calls to action from a macrosystem and ecosystem perspective:

- Ensure access for and within the community at large

- Educate the educational workforce on the value of equity, diversity, and inclusion

- Present content in a matter that is culturally relevant, recognizing and celebrating diversity

- Develop curriculum that supports indigenous students

- Foster the communities value and understanding to this specific education

- Continued action research for a continued understanding of the developing systems

Learn more:

- Western University. (2018). Guide for Working with Indigenous Students: Interdisciplinary Development Initiative in Applied Indigenous Scholarship. https://teaching.uwo.ca/pdf/teaching/Guide-for-Working-with-Indigenous-Students.pdf

References

Fuller, J., Luckey, S., Odeon, R., & Lang, S. (2021). Creating a Diverse, Inclusive, and quitable Learning Environment to Support Children of Color’s Early Introductions to STEM. Translational Issues in Psychological Science. 7 (4). p. 473-486

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2017). Supporting Success

For Indigenous Students. Directorate for Education and Skills. https://www.oecd.org/education/Supporting-Success-for-Indigenous-Students.pdf

Hire Indigenous Instructors and Elders-in-Residence

Increasing the presence of Indigenous peoples in leadership roles is likely the most impactful thing that can be done to Indigenize and Decolonize the educational system. The more Indigenous instructors or Elders that can be involved throughout the educational process, the stronger the voice of Indigenous knowledges can be.

Having Indigenous leaders in positions of power can help to promote the inclusion of Indigenous knowledges in education (Tsosie et al., 2022). Indigenous peoples enextricable hold unique knowledge of people, place, history and culture, and with their empowerment and presence they may bring Indegenous Knowledges to an institution (Tsosie et al., 2022).

“there’s a whole set of knowledge that [Elders] have that nobody else has that they open up.”

– Leduc as cited by Iqbal (2017)

Martin and Drees (2011) conducted a study to better understand the value and impact of Elders-in-Residence at Vancouver Island University and came to the following conclusions:

- Students, faculty, and staff clearly “Elder presence at the university as a positive development and opportunity” with students heaving the strongest positive response (Martin & Drees, 2011).

- Students recognize an “all-encompassing [academic and personal] impact on their lives” from the Elders-in-Residence as Elders model “respect, trust, spirituality and support (Martin & Drees, 2011).

- “Students enjoy the benefit of intergenerational contact on campus” and enjoy the opportunity to interact with Elders outside of the classroom (Martin & Drees, 2011).

- “Students voiced concerns about the lack of institutional respect for … Elders-in- Residence,” thus suggesting a deeper and broader understanding of the two-worlds Indiengous people navigate as well as reciprocating the respect they have learned from the Elders (Martin & Drees, 2011).

Learn more:

Iqbal, M. (2017). Elders on Campus. Indigenous Land Urban Stories. https://indigenouslandurbanstories.ca/portfolio-item/elders-on-campus/

References

Iqbal, M. (2017). Elders on Campus. Indigenous Land Urban Stories. https://indigenouslandurbanstories.ca/portfolio-item/elders-on-campus/

Martin, M. & Drees, L. (2011). Elders-in-Residence at Vancouver Island University: Transformational Learning. Vancouver Island University. https://indigenous.viu.ca/sites/default/files/aboriginal-education-transformational-learning-final-report.pdf

Tsosie, R., Grant, A., Harrington, J., Wu, K., Thomas, A., Chase, S., Barnett, D., Hill, S., Belcours, A., Brown, B., & Sweetgrass-She Kills, R. (2022). The Six Rs of Indigenous Research. Tribal College: Journal of American Indian Higher Education. 33 (4). https://tribalcollegejournal.org/the-six-rs-of-indigenous-research/

Adopt / Develop Calls to Action

Adopting calls to action is a powerful tool that organizations can use to ensure continued efforts towards the goals of Indigneiation and Decolonization. They can allow for systemic changes by providing a clear and comprehensive framework that defines specific actions and creates a sense of accountability and urgency.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (2015) conducted extensive research and ultimately developed the Calls to Action. This is an extensive list of action items that Canadian and Canadian organizations should adopt in order to address the legacy of residential schools and to address reconciliation. Some of the Calls to Action that pertain to trades education are:

- Addressing educational and employment gaps (7, 8, 9, 10)

- Addressing financial barriers (8, 9, 10, 11)

- An understanding of Indigenous history and persecution (62 i)

- Establishing Indigneous knowledge and teaching methods (12, 62 ii, iii)

View the entire Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to ActionCalls to Action (2015) here: https://ehprnh2mwo3.exactdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Calls_to_Action_English2.pdf

Success Story:

The Indigenous Design and Planning Student Association (IDPSA) at the Faculty of Architecture, University of Manitoba, serves as an excellent example of how such an approach can be effective. By developing a set of calls to action and working to get the university to adopt them, the IDPSA has created a framework that will guide future efforts in addressing Reconciliation. By committing to these calls to action, the university and the IDPSA are working towards a shared vision of creating a more inclusive and just society. This shows the potential for the adoption of calls to action to drive real change and create a positive impact in communities.

The IDPSA Calls to Action (2021) include aspects on Indigenous recruitment, representation, advocacy, and support, as well as developing a foundational understanding for all students and staff. View the full IDPSA Calls to Action here: https://umanitoba.ca/architecture/sites/architecture/files/2021-06/idpsa_2021_calls-to-action.pdf

References

Indigenous Design and Planning Student Association. (2021). Calls to Action. Faculty of Architecture, University of Manitoba. https://umanitoba.ca/architecture/sites/architecture/files/2021-06/idpsa_2021_calls-to-action.pdf

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). Calls to Action. Winnipeg, Manitoba. https://ehprnh2mwo3.exactdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Calls_to_Action_English2.pdf