9 History of colonization

History of Colonization

Key Events of Colonization in Canada

European colonization of the Americas is responsible for the largest genocide in history, far greater than the Holocaust, killing an estimated 80% of Indigenous peoples – seeing the population decline from around 75 million in 1492 to around ten million in North and South America (Ostler, 2019). These murders were conducted through bio-warfare tactics (disease), brutal force, sexual assaults, and more advanced weaponry, such as guns (Ostler, 2019; Diamond, 1997). Some “Europeans intentionally [inflicted] Indians with disease (usually through blankets infected with smallpox)” (Ostler, 2019, p. 842).

Indigenous peoples who resisted European trade and sought to preserve their culture and way of life became vulnerable, as they were deprived of important resources and defenses such as firearms (Vaillant, 2006; Ostler, 2019). These groups were more vulnerable to attacks from Europeans and other Indigenous groups who had access to guns, leading to the destruction and displacement of many communities who resisted colonization (Vaillant, 2006; Ostler, 2019).

The genocides continued beyond the periods of first contact and became an organized and political strategy by settlers. Before Canada became a nation, circa the seventeenth century,

“Catholic missionaries and religious orders established boarding schools to educate, convert, and assimilate First Nations children. The goal was to turn Indigenous children into obedient subjects of the French Crown, part of an ambitious plan to grow New France’s population through the cultural and religious assimilation of allied First Nations.” – Berthelette (2023)

Similar strategies continued for centuries, evolving into a systematized and entrenched process. Canada formed the Department of Indian Affairs where Duncan Campbell Scott in 1918 infamously said:

“I want to get rid of the Indian problem. I do not think as a matter of fact, that the country ought to continuously protect a class of people who are able to stand alone… Our objective is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic and there is no Indian question, and no Indian Department.”

The attack on Indigenous culture was institutionalized through laws such as the Indian Act, which “stripped people of their traditional names, devalued women, outlawed cultural practices, [and] replaced traditional leadership with elected leaders” (Joseph, 2018). It also relocated communities onto reserves and undermined their independence, severely threatening cultural continuity (Joseph, 2018). Notably, from 1884 to 1951, the Potlatch—a vital cultural ceremony—was banned, highlighting the deliberate efforts to suppress Indigenous culture (Gray, 2014).

Residential schools were another tactic in an “attempt to educate and convert Indigenous youth and to assimilate them into Canadian society,” (Residential Schools in Canada, 2023) implemented by the Canadian Government. Indigenous Children were forcibly removed from their families (Residential Schools in Canada, 2023). An estimated 150’000 children attended residential schools and of those, an estimated 6’000 died, and never returned to their families (Residential Schools in Canada, 2023). and have been recently discovered in mass graves within the school grounds (Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc Kukpi7, 2021). The first residential school opened in 1828 and the last closed in 1997 (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015).

Children as young as 3 were forced, by law, to leave their families and communities to live at schools designed to “kill the Indian in the child” (RCAP, 1996). These schools taught Aboriginal children to be ashamed of their languages, cultural beliefs and traditions, and were largely ineffective at providing proper or even adequate education (Deiter, 1999; Friesen & Friesen, 2002). In addition to the significant number of mortalities and children who went “missing” from these schools, many were also victims of chronic mental, physical, and sexual abuses and neglect (RCAP, 1996). Not surprisingly, IRS Survivors have been more likely to suffer a variety of mental and physical health problems compared to Aboriginal adults who did not attend (First Nations Centre, 2005). – Bombay, Matheson, Anisman (2014)

Traditional Indigenous philosophies posit The Seventh Generation Principle which teaches that healings and traumas that happened to one’s ancestors are passed down to children from as many as seven generations before (Bombay, Matheson & Anisman, 2014). The horrendous and extensive years of traumas inflicted upon the Indigenous Peoples of Canada continue to be felt today through intergenerational trauma as well as systemic racism (Bombay, Matheson & Anisman, 2014).

Basic human needs are made inaccessible to some. Social justice and social equity remain poor. Access to clean water, insufficient housing or no housing, and on-going discrimination are just some of the problems Indigenous peoples face (United Nations, 2015). “Indigenous women and girls are disproportionately affected by life-threatening forms of violence, homicides and disappearances” (United Nations, 2015). Indigenous people are overrepresented in the criminal justice system with 28% of the population in federal institutes identifying as Indigenous, while Indigenous people only represent 4% of the Canadian population, as reported in 2018 (Department of Justice Canada, 2023). There have been numerous reports of the “extinguishment of indigenous land rights and title” often carried out through private means and are considered legally permissible by the Canadian government (United Nations, 2015).

Truth and reconciliation is a call for social equity. Indigenous peoples of Canada continue to suffer the effects of the traumas inflicted on them by white settlers. It is our moral obligation to ease this suffering by way of offering unwavering support, compassion, and assistance in an effort to support the many generations to come that will still be impacted by these traumas.

Activity:

Reflect individually in a journal and/or engage in a group discussion on the following questions:

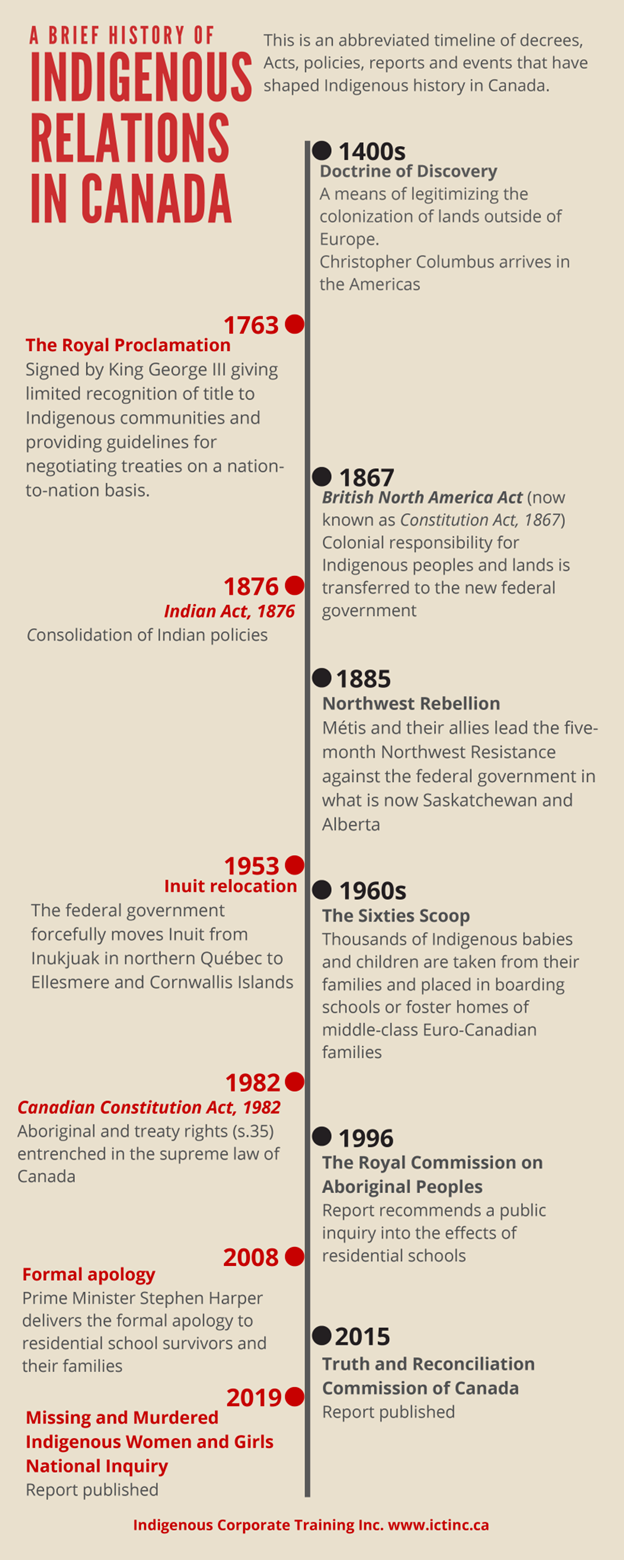

- How do the historical timelines of Indigenous peoples in Canada intersect with your own family’s history, including your ancestors such as parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents? What were you or your ancestors doing during key events such as the Indian Act (1876) or the Sixties Scoop, (1960).

- How have colonial policies and practices affected you and your family’s lineage or current social standing. How does this awareness affect your perspective on reconciliation and Indigenous rights?

- Can you imagine what it’s like to be a child taken from your family, or a parent rendered powerless in such a situation? Being forced to endure an overwhelming scale of injustice without any means to resist has persisted across generations. How would your culture remain after centuries of such experiences?

- How has the history of Indigenous peoples in Canada been taught or represented in your education? How has this influenced your perception of Indigenous communities and their historical and ongoing struggles?

- Do you think the historical and current experiences of Indigenous peoples in Canada could be compared to slavery? Consider aspects like loss of autonomy, cultural suppression, and forced assimilation. Was there ever a point where Indigenous peoples were legally or culturally considered slaves, and what features of their treatment might support or challenge this idea?

- Explore your personal connection to the Land in which you live or grew up on. How does this connection, or the lack of it, inform your views on land rights and environmental stewardship?

Learn more:

- Detailed Timelines:

- ○ Historica Canada. (2018). Key Moments in Indigenous History Timeline.

http://education.historicacanada.ca/en/tools/495 - ○ com (2022). Native American History Timeline. History. https://www.history.com/topics/native-american-history/native-american-timeline

- ○ Historica Canada. (2018). Key Moments in Indigenous History Timeline.

- Historica Canada. (2018). Indigenous Perspectives Education Guide. http://education.historicacanada.ca/en/tools/493

- National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Woman and Children. (2023). Home. https://www.mmiwg-ffada.ca/

- Residential Schools

- ○ Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). Residential Schools: A Reading List. https://www.tdsb.on.ca/Portals/0/Community/docs/ResidentialSchoolsReadingList.pdf

- ○ Wells, A., & Sanfilippo, J. (2016). Wawahte: Stories of Residential School Survivors (documentary). Wawahte. SoudWise.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oGrJNUCQ-r4&ab_channel=SoundWise

- Sixties Scoop

- ○ Indigenous Foundations (2023). Sixties Scoop. University of British Columbia: Faculty of Arts. https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/sixties_scoop/

- The Educational Systems

- ○ Battiste, M. (2021). Indigenous Knowledge In Education. Learning with Syeyutses. Nanaimo Ladysmith Public School & UBC Press. https://trc57speakerseries.ca/speakers/marie-battiste/

- ○ Carr-Stewart, S. (2021). Decolonizing Canada’s Education System. Learning with Syeyutses. Nanaimo Ladysmith Public School & UBC Press. https://trc57speakerseries.ca/speakers/sheila-carr-stewart/

- Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation. (2019). The History of Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation. https://www.ncncree.com/about-ncn/our-history/

References

Berthelette, S. (2023). Indigenous Residential Schools in New France. Defining Moments Canada: Bryce100. Retrieved from https://definingmomentscanada.ca/bryce100/history/residential-schools-in-new-france/

Bombay, A., Matheson, K., & Anisman, H. (2014). The intergenerational effects of Indian Residential Schools: implications for the concept of historical trauma. Transcultural psychiatry, 51(3), 320–338. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461513503380

Department of Justice Canada. (2023). Overrepresentation of Indigenous People in the Canadian Criminal Justice System: Causes and Responses. https://justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/jr/oip-cjs/p3.html

Diamond, J. (1997). Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies. W. W. Norton.

Gray, R. R. R. (2014). Repatriating Indigenous Cultural Heritage: What’s Reconciliation Got to Do With It? Intellectual Property Issues in Cultural Heritage. Retrieved from https://www.sfu.ca/ipinch/outputs/blog/repatriating-indigenous-cultural-heritage-what-s-reconciliation-got-do-it/

Joseph, B. (2018). Why Continuity of Indigenous Cultural Identity Is Critical. Indigenous Corporate Training Inc. Retrieved from https://www.ictinc.ca/blog/why-is-indigenous-cultural-continuity-critical

Nutton, Jennifer & Fast, Elizabeth. (2015). Historical Trauma, Substance Use, and Indigenous Peoples: Seven Generations of Harm From a ” Big Event “. Substance Use & Misuse. 50. 839-847. 10.3109/10826084.2015.1018755.

Ostler, J. (2019). Surviving Genocide: Native Nations and the United States from the American Revolution to Bleeding Kansas. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Residential Schools in Canada. (2023). The Canadian Encyclopedia. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/residential-schools

Vaillant, J. (2006). The Golden Spruce: A True Story of Myth, Madness and Greed. Vintage Canada.

Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc Kukpi7. (2021). Media Release. https://tkemlups.ca/wp-content/uploads/05-May-27-2021-TteS-MEDIA-RELEASE.pdf

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future: Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2015/trc/IR4-7-2015-eng.pdf

United Nations. (2015). International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Human Rights Committee: Concluding Observations on the Sixth Periodic Report of Canada. CCPR/C/CAN/CO/6.