8 It Is All Relationships

The Four R’s – Respect, Relevance, Reciprocity, Responsibility

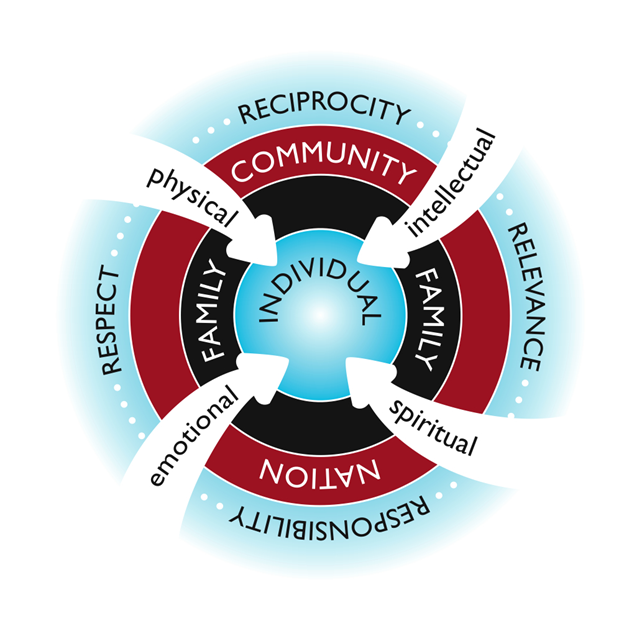

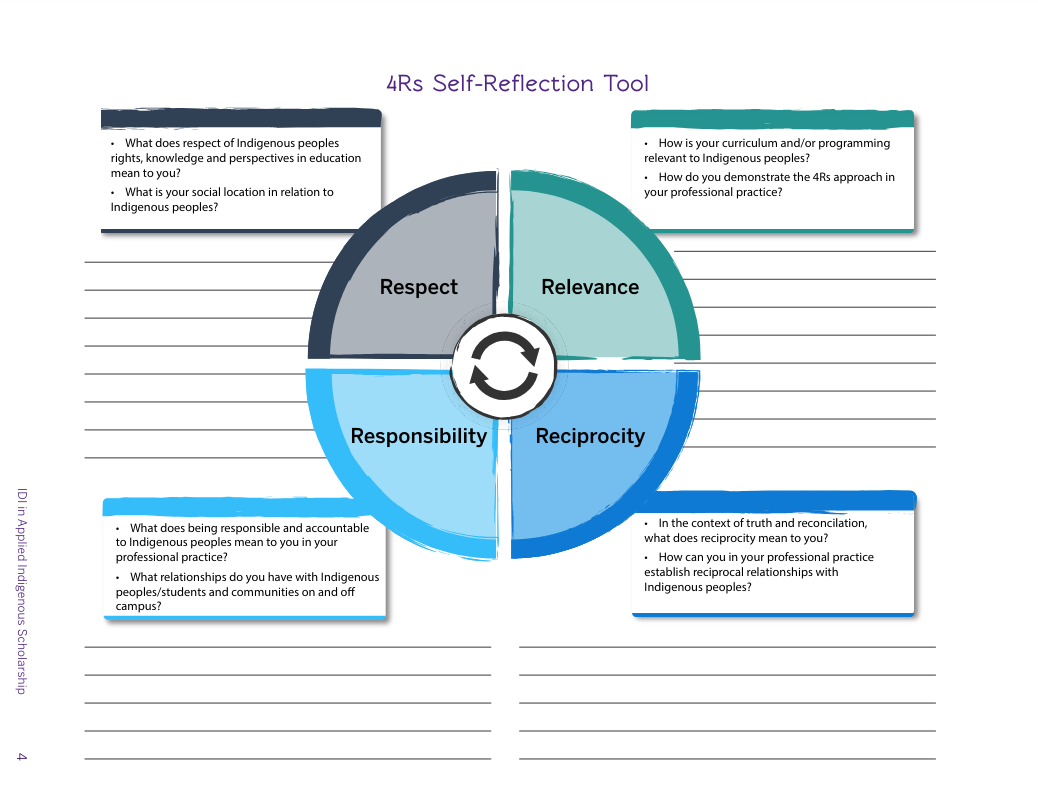

Through analyzing why post-secondary institutes lack proportional representation of Indigenous peoples, Kirkness and Barnhardt (2001) have developed the 4Rs Framework. “This framework recognizes the holistic and interconnected nature of Indigenous knowledge systems and Indigenous learners” (Western University, 2018) and emphasizes a learner-centred approach offering an understanding of how to tailor a learning environment.

● respect of cultural integrity;

● relevance to perspective and experience;

● reciprocity in learning, knowledge, and social hierarchy; and

● responsibility to facilitate an Indigenous voice.

The Four R’s can act as a guiding framework for Indigenizing education.

It is important to note that the Four R’s are a Eurocentric model. Some Indigenous people do not have ‘R’ in their language.

Activity:

Immerse yourself with the 4Rs Self-Reflection Tool (Western University, 2018)

Tool below:

References

Pidgeon, M (2014). Moving Beyond Good Intentions: Indigenizing higher education in British Columbia universities through institutional responsibility and accountability. Journal of American Indian Education, 53(2), 7-28.

Kirkness, V. J. and Barnhardt, R. (2001). First Nations and Higher Education: The Four R’s – Respect, Relevance, Reciprocity, Responsibility. Knowledge Across Cultures: A Contribution to Dialogue Among Civilizations. R. Hayoe and J. Pan. Hong Kong, Comparative Education Research Centre, The University of Hong Kong http://www.ankn.uaf.edu/IEW/winhec/FourRs2ndEd.html

Western University. (2018). Guide for Working with Indigenous Students: Interdisciplinary Development Initiative in Applied Indigenous Scholarship. https://teaching.uwo.ca/pdf/teaching/Guide-for-Working-with-Indigenous-Students.pdf

Self-location / Positionality

Self-location

“Territory acknowledgements are traditional Indigenous gathering protocols that honour and recognize the Indigenous peoples who have deep historical and significant ties to the lands where the gathering is taking place. The territory protocol is an ancient cultural practice of Indigenous Nations across Turtle Island (North America) and is essential in demonstrating our commitment to reconciliation by reversing the forced erasure of Indigenous peoples by colonial Canada.”

This protocol of acknowledgment is still in practice today between Indigenous groups in North America. When visiting another Indigenous group’s territory, the visitors ask for permission to be on the Land and conduct a certain activity, often presenting a gift to a local Elder or leader and always respecting local protocols and traditions.

Pierre (2022), outlines guidelines for a territory acknowledgement as well as methods to elevate an acknowledgment from a standard to a reflective and transformative one. A transformative acknowledgement is spoken from the heart and “acknowledge[s] concepts like colonialism, anti-racism, reconciliation, and settler power/privilege and institutional oppression,” (Pierre, 2022).

You may find it helpful to reflect on and research questions such as:

■ Why am I sharing this acknowledgement? Why am I choosing this medium/context to do this?

■ How does this acknowledgement relate to the event or work I am doing?

■ What is the history of this territory? What are the impacts of colonialism here?

■ What is my relationship to this territory? How did I come to be here? How did I or my ancestors come to be here? Have my ancestors always been here? What does this mean to me? How do I remain accountable?

■ What are your ethical and political commitments and obligations to this land and Indigenous Peoples?

■ What intentions do you have to disrupt and dismantle colonialism beyond this territory acknowledgement?

(Queen’s University: Centre for Teaching and Learning, 2023)

Activity: Develop a transformative territory acknowledgement that is personal and for the land you live, work, and play on.

Positionality

“Determining your positionality requires you to reflect on your multiple identities based on group memberships, roles and personal values and characteristics and to consider how your lived experiences and perceptions may influence your research questions, methods and the way you interpret research findings.” (Harrington, 2022)

From Harrington, 2022:

What Is Your Instructor Positionality?

Ask yourself the following questions:

● What groups—race, gender, sexual orientation, age, social class, religion, ability and so on—do I identify with and how salient is each group membership to my identity and related actions as an instructor?

● What roles—significant other, parent, sibling, child, friend, instructor, scholar, author—do I have and how do these impact my identity and related actions as an instructor?

● What type of training and experiences do I have? How have they shaped who am I professionally today, and how might they positively or negatively impact marginalized populations in my classes today?

● What beliefs or values and characteristics do I have, and how do they impact my identity and related actions as an instructor?

● In what ways do my identities represent privilege or marginalization, and how might they compare to those of my students? How might I be engaging in actions that marginalize or discourage students? What actions do I take to promote student success for all the students in my classes?

Activity: On your own, write an introduction and positionality statement.

Discussion: Share and understand each others’ unique viewpoints.

References

Harrington, C. (2022). Reflect on Your Positionality to Ensure Student Success. [BLOG]. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/advice/2022/01/26/successful-instructors-understand-their-own-biases-and-beliefs-opinion

Pierre, L. (2022). Transformative Territory Acknowledgement Guide. https://www.lenpierreconsulting.com/_files/ugd/90c86d_b3aa5cd2564c4d77a72b7b397d96add0.pdf

Queen’s University: Centre for Teaching and Learning. (2023). Positionality Statement. Queen’s University. https://www.queensu.ca/ctl/resources/equity-diversity-inclusivity/positionality-statement

Two-eyed Seeing

The following is an extract from:

Marshall, A. (2017). Two-Eyed Seeing – Elder Albert Marshall’s guiding principle for inter-cultural collaboration. Thinkers Lodge. Pugwash, NS: Climate Change, Drawdown & the Human Prospect: A Retreat for Empowering our Climate Future for Rural Communities http://www.integrativescience.ca/uploads/files/Two-Eyed%20Seeing-AMarshall-Thinkers%20Lodge2017(1).pdf

Mi’kmaq Elder Albert Marshall (who lives in the community of Eskasoni, Nova Scotia, in the Traditional Territory of Mi’kma’ki) coined the English phrase “Two-Eyed Seeing” many years ago for a guiding principle found in Mi’kmaq Knowledge as reflected in the language. Elder Albert is a fluent speaker of Mi’kmaq … Two-Eyed Seeing in his language is known as Etuaptmumk.

Two-Eyed Seeing / Etuaptmumk encourages the realization that beneficial outcomes are much more likely in any given situation if we are willing to bring two or more perspectives into play. As such, it can be further understood as the gift of multiple perspective treasured by many Indigenous peoples. And our world today has many arenas where this realization, this gift, is exceedingly relevant including, especially, education, health, and environment. Elder Albert is passionate about bringing into these arenas the perspectives and knowledges of the Mi’kmaq people, of all Indigenous peoples, such that mutually beneficial, inter-cultural, collaborative relationships with mainstream society and the Western sciences can be nurtured and grown and new understandings put to work. Thus, he describes Two-Eyed Seeing as: “learn to see from your one eye with the best or the strengths in the Indigenous knowledges and ways of knowing … and learn to see from your other eye with the best or the strengths in the mainstream (Western or Eurocentric) knowledges and ways of knowing … but most importantly, learn to see with both these eyes together, for the benefit of all”. Albert acknowledges that such work is not easy and he emphasizes, therefore, that an on-going journey of co-learning is both required and essential in order to develop the profound collaborative understandings and capabilities that Two-Eyed Seeing encourages.

“learn to see from your one eye with the best or the strengths in the Indigenous knowledges and ways of knowing … and learn to see from your other eye with the best or the strengths in the mainstream (Western or Eurocentric) knowledges and ways of knowing … but most importantly, learn to see with both these eyes together, for the benefit of all” – Mi’kmaq Elder Albert Marshall

Learn more:

● Institute for Integrative Science & Health (2013): http://www.integrativescience.ca/

– Integrative Science and Health is an organization that aims to integrate a new paradigm for science that involves multiple perspectives, cultures, and communities. Two-eyed seeing is the main guiding principle.

● Thomas, R. (2016). Etuaptmunk: Two-Eyed Seeing. TEDxNSCCWaterfront https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bA9EwcFbVfg&ab_channel=TEDxTalks

● Provost, M. (2022). Unpacking the Indigenous Student Experience. TEDxSFU https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2JmAlnEo27A&ab_channel=TEDxTalks

Activity:

Reflect individually in a journal and/or engage in a group discussion on the following questions:

● How much cultural understanding and self-awareness do you think is necessary for Indigenous and non-Indigenous individuals to effectively contribute to two-eyed seeing?

● How could two-eyed seeing influence one’s worldview, relationships, and approach to problem-solving? Does two-eyed seeing demand or inspire a specific philosophy?

● How could the practice of two-eyed seeing be integrated into your daily life? How would it look different in various contexts such as home, work, play? What kind of support or change to the environment is needed to facilitate two-eye seeing?

● What are some contradictions in western ways of knowing vs. Indigenous ways of knowing? Explore concepts such as time, relationships with others and nature, or knowledge.

● How do we mediate the differences of Western ways of knowing vs. Indigenous ways of knowing and hold them both as true and valid? How can these differing views coexist or complement each other in various sectors like education, the trades, or society?

● Share any personal experiences or research historical examples where integrating multiple perspectives has led to innovative solutions or deeper understandings. What practices or mindsets can facilitate the reconciliation and validation of both knowledge systems?

References

Bartlett, C., Marshall, M., Marshall, A., & Iwama, M. (2015). Integrative Science and Two-Eyed Seeing: Enriching the Discussion Framework for Healthy Communities in Beyond Intractability: convergence and opportunity at the interface of environmental, health and social issues; edited by Lars K. Hallstrom, Nicholas Guehlstorf, and Margot Parkes. UBC Press. http://www.integrativescience.ca/uploads/files/Bartlett-etal-2015(Chap10).pdf

Institute for Integrative Science & Health. (2013). Integrative Science Home Page. Cape Breton University. http://www.integrativescience.ca/

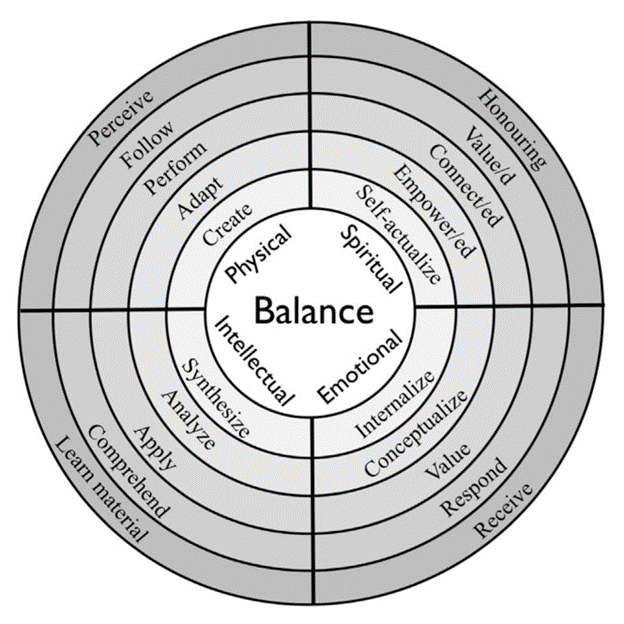

The Spiritual Learning Domain

LaFever (2016) introduces a transformative and holistic approach to learning that is rooted in the Medicine Wheel. The Medicine Wheel is a powerful symbol used by many (but not all) Indigenous peoples in North America to represent the interconnectedness of all things. By applying this framework to learning, LaFever (2016) offers a profound paradigm shift that goes beyond traditional Western education models.

Spirituality greatly influences Indigenous knowledge and perception as is reflected in their languages, where concepts of relationship, heart, and spirit are deeply embedded. This spiritual perspective fosters a holistic approach to education and understanding, where all aspects of life are interconnected and sacred.

LaFever’s (2016) framework of a spiritual learning domain is counter to Western/Eurocentric views which hold learning in isolated subjects and most importantly separated from spirituality. “Experiences are all connected”(LaFever, 2016).

Using LaFever (2016) can help transform course learning outcomes which creates a tangible way to weave in Indigenous ways of knowing. Building upon the learning domains presented by Bloom (1956), the physical, intellectual, and emotional domains, LaFever adds the spiritual domain:

The Spiritual Learning domain has at its foundation:

1. “Honouring: conscious or aware of learning that is not based in material or physical things, and transcends narrow self-interest;

2. Value/d: building relationships that honour the importance, worth, or usefulness of qualities that are related to the welfare of the human spirit;

3. Connect/ed: build/develop a sense of belonging (group identity/cohesion) in the classroom, community, culture, etc.;

4. Empower/ed: provide support and feel supported by an environment that encourages strength and confidence, especially in controlling one’s life and claiming one’s rights;

5. Self-Actualize/d: ability as a unique entity in the group to become what one is meant to be.” (LaFever, 2016).

Read LaFever’s full article: https://www.lincdireproject.org/wp-content/uploads/ResearcherShareFolder/Readings/Switching%20from%20Bloom%20to%20the%20Medicine%20Wheel.pdf

References

Bloom, B. (1956). Taxonomy of Educational Objectives Handbook I: Cognitive Domain. New York: David McKay.

LaFever, M. (2016). Switching from Bloom to the Medicine Wheel: creating learning outcomes that support Indigenous ways of knowing in post-secondary education. Intercultural Education. 27:5, 409-424, DOI: 10.1080/14675986.2016.1240496

Ecological Thinking

Ecological thinking challenges the mainstream (Western or Eurocentric) approach of ‘linear’ and human-centred thinking. In ecological thinking, one must let go of the ‘linear’ approach that holds events occurring sequentially, an emphasis of cause-and-effect, and the idea that problems have a clear solution.

Ecological thinking is a systems approach where there are complicated interrelationships that are impossible to isolate. Molderez (2020) paraphrases Benyus (1997) in Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature, looks “at nature as a model, a measure and a mentor, instead of seeing nature as only valuable because it is a source of raw materials.” Du Plessis and Brandon (2015) identify “three main themes of the ecological worldview: wholeness, relationship, and change”.

Ecological thinking employs the new materialist philosophy which emphasizes that all things, human, non-human, animate, and inanimate, have agency, autonomy, and power (Toohey, 2018). All things play a role in defining each other and the environment thus developing complex interrelationships and entanglement with one another (Toohey, 2018; Charterisa, Smardona, & Nelson, 2017). “New materialism sees people, discourses, practices and things continually in relation, under construction and changing together, becoming different from what they were before” (Toohey, 2018).

“With one particular apparatus of enquiry, light is a wave; with another, it is a particle. Barad (2007) explained that this apparent contradiction is not only because of our instrumentation; rather, she argued that light does not become ‘a thing’ until it is measured, and the instrument of measurement (as well as the measurer) is entangled with the phenomenon” (Toohey, 2018).

It is evident that one cannot isolate things from one another because their very being may be fundamentally defined by the context and may become something different in a new context. Thus a holistic viewpoint is necessary and one must contemplate, what conclusions may be incorrectly extrapolated from one context to another.

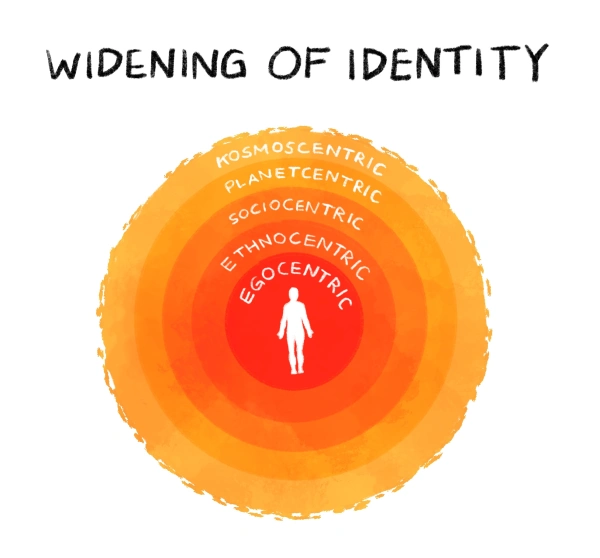

Ecological thinking requires a broadening of identity in how we see ourselves in relationship to the world around us. Hes and Du Plessis explain that “as one’s identity expands, so does one’s view of the world. With these changed perceptions also come a change in values, behaviours and possible leverage points” (2014). Sean Esbjörn-Hargens (2010) describes this ‘widening of identity’ as a transition from ‘me’ (egocentric) to ‘my group ‘(ethnocentric) to ‘my country’ (sociocentric) to ‘all of us’ (worldcentric) to ‘all beings’ (planetcentric) to finally ‘all of reality’ (Kosmoscentric). In performance practice, this could be interpreted as a widening in identity from ‘me’ as the artist to considering how I might create work that actively engages with communities as well as the ‘living world’.

– (Beer, 2014)

Some guiding practices:

● Humility: Look beyond the self. Be humble and deeply recognize humans cannot know everything. Get comfortable with the limits of your understanding as well as your group’s, community’s, society’s, and humanity’s knowledges. Welcome other ways of knowing.

● See all things (animate and inanimate) as relevant, powerful, and having autonomy.

● Avoid dichotomies: Drawing lines and splitting things up can oversimplify and hinder a complex understanding. Often dichotomies are the labelling of specific characteristics which may overlook the larger picture.

● Do not label cause-and-effect: avoid deterministic phrasing as a system is always changing and it is very, very difficult to determine cause-and-effect. Labelling something conclusively often ends the exploration of the topic.

Learn more:

● Watson, J. (2020). How to build a resilient future using ancient wisdom. TED. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_DOOJx7AZfM&ab_channel=TED

● June, L. (2022). 3000-year-old solutions to modern problems. TEDxKC. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eH5zJxQETl4

● Humboldt PBLC. (2019). Traditional Ecological Knowledge & Place-based Learning Communities. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=liKV74avPso&ab_channel=HumboldtPBLC

References

Beer, T. (2014). Ecological Thinking. Ecoscenography. https://ecoscenography.com/ecological-thinking/

Benyus, J.M. (1997), Biomimicry. Innovation Inspired by Nature, Harper Collins, Glasgow.

Du Plessis, C. & Brandon, P. (2015). An ecological worldview as basis for a regenerative sustainability paradigm for the built environment. Journal of Cleaner Production. 109. P. 53-61. ISSN 0959-6526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.09.098. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0959652614010385

Jennifer Charterisa, Dianne Smardona and Emily Nelson (2017) Innovative learning environments and new materialism: A conjunctural analysis of pedagogic spaces. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 49, No. 8, pp. 808–821 https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2017.1298035

Molderez, I. (2020). How transformative learning nurtures ecological thinking. Evidence from the Students Swap Stuff project. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education. 22 (3). pp. 635-658. Emerald Publishing Limited. DOI 10.1108/IJSHE-05-2020-0174

Toohey, Kelleen (2018) “New materialism and language learning”, Ch. 2 in Learning English at School (2nd edition) Multilingual Matters: Bristol

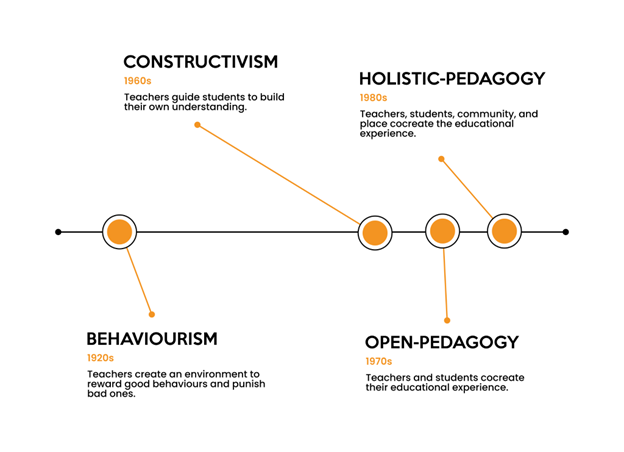

Holistic Pedagogy

If we observe some important and influential pedagogies, there is an evolution of widening the sphere of influence. Behaviourism focuses on changing the external behaviours that students exhibit through teacher reinforcement and punishment. With constructivism, learners develop their own understanding with teachers as guides. Behaviourism holds the power of teaching with the teacher, while constructivism releases some power to the learners. Open pedagogy further involves students by practicing openness “within all aspects of instructional practice; including the design of learning outcomes, the selection of teaching resources, and the planning of activities and assessment,” (Paskevicius, 2016). Holistic Pedagogy is concerned with teaching the ‘whole’ student, including spiritual and humanistic values (Rudge, 2016). The educational experience of Holistic Pedagogy may be advised by the learner, culture, community, and place. For reference, Waldorf and Montessori schools, practice Holistic Education (Rudge, 2016).

Note: The above dates are just a guidepost to help understand the people, places, and societies where these ideas gained popularity in the Western world. It is very difficult to pinpoint the origins of such ideas as they have been prevalent in one form or another for hundreds of years.

There is no ‘best’ pedagogy. Every pedagogy has strengths and weaknesses and are suitable for different learning activities and outcomes. Educators are constantly faced with the difficult task of selecting and integrating a beneficial pedagogy into their learning activities. The intent of presenting holistic pedagogy is for educators to become familiar with and to adopt aspects of holistic pedagogy for the right personal context.

Overview

Relationships are the forefront of holistic pedagogy. “Holistic education is primarily concerned with the overall development (physical, intellectual, emotional, and spiritual) of the individual” with an emphasis on wholeness and/or interconnectedness (Rudge, 2008).

“Holistic education integrates the idealistic ideas of humanistic education with spiritual and philosophical ideas; it incorporates principles of spirituality, wholeness, and interconnectedness along with those of freedom, autonomy, and democracy.”

– Rudge, 2008

Rudge (2016), through a meta-analysis, outlines eight principles split into two categories:

| Spiritual/ Holistic | Humanistic |

|

● Spirituality

● Reverence for life/nature

● Interconnectedness

● Human wholeness

|

● Individual uniqueness

● Caring relations

● Freedom/autonomy

● Democracy

|

Downsides to Holistic Pedagogy:

Implementing holistic education is time-consuming and expensive. It requires significant time and effort to truly understand the context in which the learners exist. Collaborating with others is a crucial aspect of implementing holistic education which can also be time-consuming. Effective collaboration involves working with a variety of individuals, including educators, administrators, parents, and community members to create a shared vision for education.

The emphasis on the learner can sometimes result in a de-emphasis on academic achievement, which can make it difficult to integrate with traditional curricula. The focus on the learner’s well-being and personal growth can sometimes clash with the standard academic subjects and goals. Finding the right balance between these two approaches can be challenging, but essential for holistic education to be successful.

Another difficulty with holistic education is the incorporation of spiritual and humanistic components. Spiritual and humanistic components require a different way of thinking and may not fit within the traditional academic framework. However, integrating these components is crucial to creating an education that addresses the learner’s needs holistically.

Holistic education is a comprehensive approach that can lead to a well-rounded education for learners but requires significant time, effort, and resources to implement.

Learn more:

● Canadian Council of Learning. (2007). First Nations Holistic Lifelong Learning Model https://firstnationspedagogy.com/CCL_Learning_Model_FN.pdf

● Nehinuw (Cree) Pedagogy

https://trc57speakerseries.ca/speakers/linda-goulet-keith-goulet/

● Redvers, T. (2017). Creating environments for Indigenous youth to live & succeed. TEDxKitchenerED https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zwLR23fHBQU&ab_channel=TEDxTalks

Activity:

Reflect individually in a journal and/or engage in a group discussion on the following questions:

● Can you share examples where you’ve observed or personally experienced a significant enhancement in the academic journey of students through supportive measures? What specific support strategies were implemented, and how did they contribute to the improvement in students’ learning experiences, engagement, or academic outcomes?

● What challenges do you anticipate when introducing holistic pedagogy into your institution’s academic culture, and what strategies could effectively address these obstacles?

References

Rudge, L. (2008). Holistic Education: An Analysis Of Its Pedagogical Application. [Doctoral Dissertation, The Ohio State University].

Rudge, L. (2016). Holistic Pedagogy in Public Schools: A Case Study of Three Alternative Schools .Other Education: The Journal of Educational Alternatives ISSN 2049-2162 5 (2). pp. 169-195

Paskevicius, M. (2016). Conceptualizing Open Educational Practices through the Lens of Constructive Alignment. 2017 Open Education Global Conference Selected Papers. Open Praxis. 9 (2). pp. 125–140. https://doi.org/10.5944/openpraxis.9.2.519

Two-Spirited People

The two-spirited person originates from ancient Indigenous traditions, even being represented in some of the earliest known artifacts (Laframboise & Anhorn, 2008). These beliefs tell a story of an understanding that gender is non-binary, embracing cross-gender roles. Colloquially, two-spirited people may also identify with terms such as gender fluid, gender queer, or transgender, but this term can even be used more broadly to encompass the entire LBGTQ2S+ community within an Indigenous context.

“Systematic dismantling of indigenous religions, education, and social structures has led to an internalized and externalized homophobia, transphobia, and sexism that contemporary Two-Spirit people must contend with in addition to the xenophobia, racism, and classism from larger American societies.” (Pizzi, 2013).

Cultural sensitivity and cultural safety are essential in providing this community space to overcome these numerous barriers. It will take a collective community effort to support this group to empowerment.

Learn more:

● Prudan, H. (2013). Two-Spirit Resource Directory. National Confederacy of Two-Spirit Organizations and NorthEast Two-Spirit Society. https://idlenomore.ca/native-youth-sexual-health-network/

● Laframboise, S., & Anhorn, M. (2008). The Way Of The Two Spirited People: Native American concepts of gender and sexual orientation. Dancing to Ragle Spirit Society. http://www.dancingtoeaglespiritsociety.org/twospirit.php

● Makokis, J., & Walters, K. (2021). Two Spirit and Indigiqueer cultural safety: Considerations for relational practice and policy. Indigenous Cultural Safety Collaborative Learning Series. https://www.icscollaborative.com/webinars/two-spirit-and-indigiqueer-cultural-safety-considerations-for-relational-practice-and-policy

● Driskill, Q. (2022). Cherokee Queer and Two-Spirit Memory – Stories of Asegi. Learning with Syeyutses. Nanaimo Ladysmith Public School & UBC Press. https://trc57speakerseries.ca/speakers/qwo-li-driskill/

References

Pizzi, D. (2013). Model of Change: Two Spirit Population. SW6010: Race, Gender, and Inequality in Social Work. http://www.dancingtoeaglespiritsociety.org/essays/model_for_change.pdf

Laframboise, S., & Anhorn, M. (2008). The Way Of The Two Spirited People: Native American concepts of gender and sexual orientation. Dancing to Ragle Spirit Society. http://www.dancingtoeaglespiritsociety.org/twospirit.php