9 Turns of the Century

1897 to 1903, continued

__________________________

“The Colonel was a man of forceful personality, jealous of his title and of the respect his generous gifts commanded.”

— Edwin O. Palmer in his History of Hollywood

The Golden Age of Griffith Jenkins Griffith lasted just under seven years. From December 16, 1896, to September 3, 1903, to be exact. And it wasn’t just about his beloved Griffith Park. It was turn of the 20th Century, and turns were happening everywhere. So much changed in so little time around the world, in this corner of the world, and in Grif’s world, where donating the park was just the start. For Grif, it meant transitioning from rural land baron, to gilded elite, to Progressive reformer and then, at his peak, to benevolent capitalist.

Globally, the Second Industrial Revolution was at full force, while European nations threatened or were at war to protect or expand empires. The United States, too, cut its young teeth on the Spanish-American War in 1898. But for the most part, U.S. ambitions were still focused on expanding within its borders, especially since transcontinental railroads had just opened the West.

Los Angeles was in a teenage growth spurt, having doubled to 100,000 souls from 1890 to 1900 in large part due to the “Land of Sunshine” marketing campaign aimed at Easterners and Midwesterners. An 1897 Then and Now book touted by boosters listed some of the advances since 1882, when the local population was just 12,000:

- From zero paved streets to almost 200 miles of graded and graveled roads; and 135 miles of paved and asphalt “footways”, i.e. sidewalks;

- From a single, horse-drawn transportation system to 127 miles of transit lines, 98% of them using electric rails;

- Last, but not least, from 10 miles of sewer lines to 141, including a 12-mile outfall line to deposit waste in the ocean.[1]

Downtown was the most developed area, much of it now having paved sidewalks and arc lighting, the predecessor to the electric light bulb. No longer was it just the Baker Block for business matters, as other buildings sprouted to accommodate a Chamber of Commerce, a stock exchange and even a mining exchange. Two railways competed into and out of the city, while short rail lines spread like veins to areas where the railway owners had previously bought property that they could later sell — a shrewd way to improve returns on investment! And a world-class shipping port was being built in nearby San Pedro to open trade to the Far East.

But a major, modern city Los Angeles was not — yet. “The year 1900 found Los Angeles an eclectic, patchwork sort of place,” historian Kevin Starr noted in Inventing the Dream.[2] It was old-fashioned Spanish Southwest meets pioneering American Midwest, as the sights and sounds of old and new flooded the streets of downtown: “the clang-clang and rattle-rattle of electric streetcars along Broadway, Spring and Main streets; the clippety-clop clippety-clop of horsedrawn buggies and wagons; the staccato beat of swiftly passing hansom cabs; the occasional whir of electric buggies; and even now and then the cough and sputter of a combustion engine.” That’s right, that sputter was the gasoline-powered automobile and Los Angeles even had its own auto manufacturer by 1897, the first sign of what the city later became known for — its car culture.

As for real culture, Los Angeles still felt like a glorified Wild West town, not a Chicago, New York or even San Francisco. Sure, an opera season was established in 1887 at the height of the Boom, but Angelenos were more loyal patrons to their 200 saloons. “To be frank,” Starr wrote, “turn of the century Los Angeles had little in the way of formal culture … but there were signs of developing urbanism that fought against the unsophisticated boom-town tone that dominated.”

He even cited Grif and his park as a prime example of a more cultured city coming into its own. It took a few more decades, Starr noted, but eventually Los Angeles “enjoyed an excellent network of open spaces” thanks to Grif and later park planners.

‘Jealous of his Title’

Los Angeles and its downtown didn’t offer the bustling urban life of, say, San Francisco, but it still was plenty more sophisticated than the rancho. So even after marriage and a son, Grif did not give up the downtown lifestyle for a quiet spread surrounded by nature. Instead, the Griffiths rented a house downtown for their first year as a family, and then moved to suites at the United States Hotel, which was owned by Tina’s family. That was followed by several years at the Nadeau Hotel, which had become the city’s center of social and business life, and then in 1902 the new Fremont Hotel.

The lifestyle allowed Grif to become a man about (down)town – dressed to the nines and making his way back and forth between hotel, office, club, barbershop and, as we’ll see later, saloon. Tina would, of course, join Grif for opera nights and the Saturday dances at the Jonathan Club. But otherwise she and son Van were mostly on their own. Tina’s outings focused on playing the card game whist with lady friends and assisting the Catholic charity for orphans.

Grif had always liked to promenade, and Griffith Park certainly gave him a new aura that he enjoyed — but which could come across as boorish. “The Colonel was a man of forceful personality, jealous of his title and of the respect his generous gifts commanded,” Hollywood pioneer Edward O. Palmer wrote in History of Hollywood, a 1937 account of early tinsel town.[3] Palmer saw and heard plenty from Grif as the latter became an early investor in Hollywood. “His rather long, jet-black hair, heavy brows, heavy, well-curled mustache, round face, and square-built, robust stature so set off his silk hat, frock coat, boutonniere, and crooked cane as to mark him a person of importance in the informal community,” Palmer noted, And his speeches, well those “seemed a source of extreme satisfaction to him, particularly when bestowing floral tributes on his business associates.”

Overall, though, Grif was mostly tolerated by his wealthy peers — not because he was lovable but because he had money and he wanted to be involved. It was money that allowed Grif to transition from rancher to lender in the 1880s, and then to dependable do-gooder, Hollywood developer and even industrialist during his turn-of-the-century heyday. Those do-good virtues were highlighted by the weekly Capital in a full-page article titled “Sir Griffith” and in which Angelenos were told they “can never do him too much honor”.

Later Capital accolades cited his connections — from being “close to the throne” of Teddy Roosevelt, to having investment savvy. It even speculated that Grif could become a railroad tycoon given “he possessed that necessary combination, self-confidence and sagacity joined to daring and combativeness.” To boot, The Capital stated, “Griffith probably has more ready money at his command than any other man in Los Angeles.”

Money was also always center stage in the Griffith marriage. Yes, Grif did arrive in Los Angeles with his own fortune, and made more early on by selling water rights to the city. But it was Tina’s inheritance, which he quickly took control of, that changed the path of the Griffith family history. Of course, Grif would never admit that, but he pretty much said so on December 16, 1896, telling his City Hall audience that he’d long wanted to donate land for a park but was only able to do so now that his finances allowed it. Those finances hadn’t improved because of any rancho profits, but because, over the previous decade, Grif had sold off Tina’s Briswalter property in various tracts that netted at least $1.2 million. That bought a lot of wealth back then – compare it to a teacher’s wage of around $750 a year, or residential property lots that cost $300.

All that cash created new opportunities for Grif — and eventually tensions with Tina. The years 1897 and 1898 saw Grif dive into community issues, donating to fundraisers for the unemployed and poor children; traveling to Washington, D.C., on behalf of citrus growers to lobby for tariff protection; arguing that utilities like water and public transit should not be in private hands; and signing up as treasurer of the new Nicaragua Canal Association.[4] In a town not known for philanthropy, Grif was the (if not the only) model citizen.

That year, Grif’s Fiesta “knighthood” brought him new prestige, and Grif became a central figure at the elite Jonathan Club, where he liked to regale (some would say bore) fellow members with stories. His club reputation made it into the press, where one day he might be cheered as the “star ‘Josher’” with the “two-by-four smile”, and another day be mocked as a self-centered speechmaker who used “I” so often at one club event that all but one attendee left. The lone listener, it was reported, had been captivated by Grif’s “glittering I.”[5]

Networking with Teddy and Otis

The Jonathan Club also offered Grif a place to practice politics. Many members were Republicans in what was known as the “Progressive” wing, fighting as Grif put it in a letter to the editor, “to escape from slavery under the political boss” by ensuring clean elections and nonpartisan fire and police chiefs.[6]

Grif’s first political foray was co-founding the Citizen’s League in 1893 and he later toyed with the idea of running for mayor — until an exploratory “mass meeting” at the Chamber of Commerce was attended by just 17 people. Grif was so irate on reading the media mockery the next day, a Herald columnist wrote on July 13, 1900, that he “gave one of the best imitations of a raving maniac I ever saw.”

Grif did keep his hand in local politics, serving as a delegate to the 1900 national Republican convention. That’s where he first met Col. Theodore Roosevelt, then a former New York governor seeking even higher office. Los Angeles is sending “the flower of its manhood and citizenry,” the same Herald columnist gushed. “Griffith’s well-known and justly admired graces of mind and body are accompanying him on his pilgrimage to the Republican shrine.”

In May 1901, when President McKinley, a Republican, visited Los Angeles, Grif was among those invited to the reception at the mansion of Times owner Harrison Gray Otis. Just four months later, McKinley was assassinated, and Grif was appointed to chair the local services commemorating his life. More significantly, McKinley’s demise led to the rise of the vice president, who happened to be Roosevelt. Now, Grif’s political star was shining even brighter. He “is in much demand these days,” declared the Capital, “for the word has been passed along the highways and biways that Col. Griffith is to be exquisitely close to the throne” given the “attachment” formed between him and Roosevelt at the convention.[7]

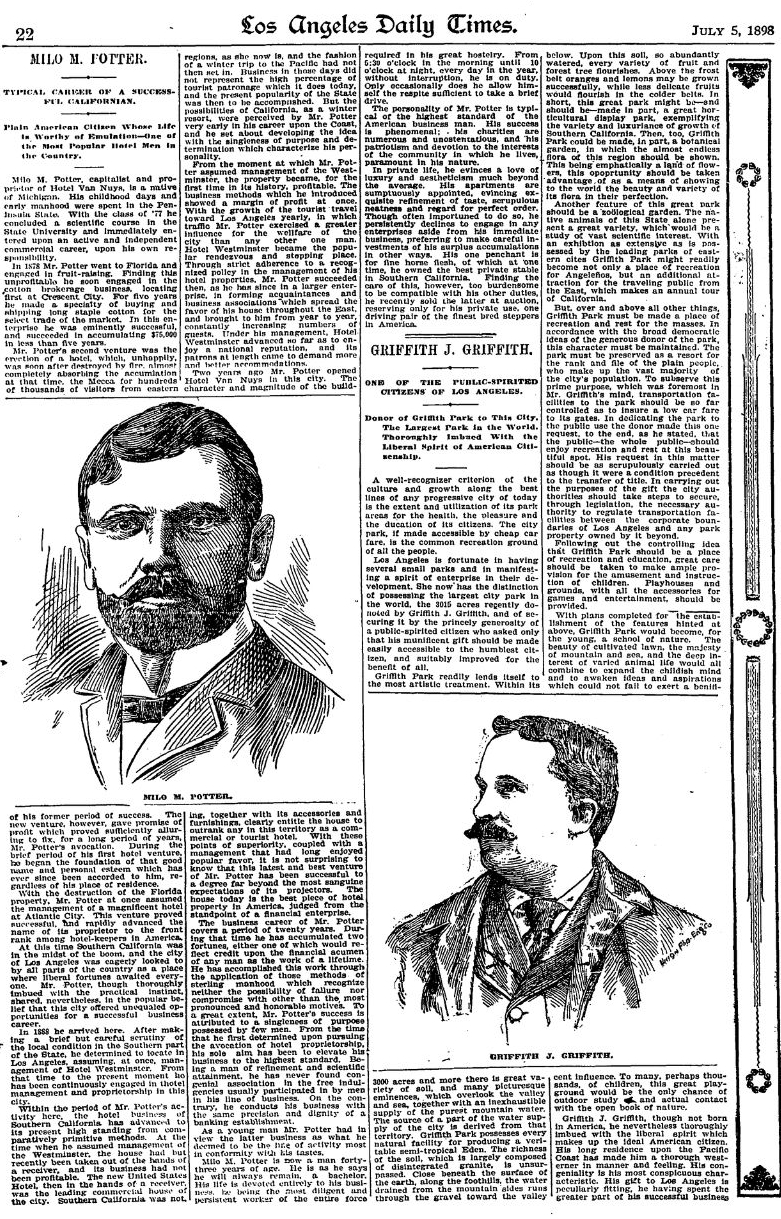

Grif’s ascendancy also caught the attention of the Times, which prior to the park donation had paid him little attention. On January 1, 1898, it featured him in a “Men of Achievement” special section, complete with a large, flattering pen portrait. Among the builders of Los Angeles, the profile went, “none is more entitled to recognition than Griffith J. Griffith. No need to ask ‘Who is G. J. Griffith?’ The individuality of the man has impressed itself so deeply and favorably on this community that his name is even a ‘household word’.”

Six months later, on July 5, he was back for the Times’ “Patriotic War” edition, where a new profile and pen portrait focused on “the princely generosity of a public-spirited citizen who asked only that his munificent gift should be made easily accessible to the humblest citizen, and suitably improved for the benefit of all.” The Times was celebrating U.S. military might in the midst of the war against Spain in Cuba, and used the various profiles to showcase patriotic Americans, honoring the Wales-born Grif as one of its own. “Griffith, though not born in America,” it stated, “he nevertheless is thoroughly imbued with the liberal spirit which makes up the ideal American citizen.”

Moreover, up to this point the Times had only rarely described Grif as “Col. Griffith” — even though the Herald had started doing so in 1886. But Grif became “Col. Griffith” to the Times on December 15, 1898, and with that came another sign that Grif had made it.

The question remains if Grif actually bought some of that goodwill. Was Grif’s secretary, the one charged with embezzlement, telling the truth when he alleged Grif paid newspapers $10,000 to support his park donation? There’s no solid proof, but it was later shown that in June 1897 Grif transferred to Times owner Otis a 1.5-acre lot downtown for just $1. He followed that up in April 1902 by with a Los Feliz lot transfer of $1.[8]

Either way, there’s no doubt Grif also continued with good deeds, and not just having to do with the park or politics. At the turn of the century, he helped start a Welsh social club; donated to a relief fund for victims of the deadly hurricane in Galveston, Texas; dabbled in the Southern California Academy of Sciences; paid for free Central Park concerts as a way to drown out a speaker’s corner that many felt had made the park unpleasant; and even invested $100 to start a local team for the fledgling National Baseball Association.[9]

Harbor Heyday

Grif also saw the culmination of four years’ lobbying for — and, again, helping fund the fight for — a deep water harbor that would not be monopolized by the Southern Pacific railway. The “free” harbor advocates wanted the federal government to finish the port at nearby San Pedro that it had first started funding, in piecemeal fashion, in 1872. The SP wanted the deep-water harbor in Santa Monica, where it controlled the rail line and already had a long wharf.

Both sides knew the harbor would open a door to trade with Asia and, once a long-talked about canal in Central America was completed, provide easier ship access to the East Coast and Europe. The United States was also starting to acquire a taste for expansion abroad, having defeated Spain in December 1898. That gave U.S. access to Cuba and, more importantly, a new U.S. territory by way of the Philippines from which to build a trading post. Annexing Hawaii that same year didn’t hurt trade prospects either.

In early 1899, the McKinley administration formally backed the San Pedro site, and plans were made for a “Free Harbor Jubilee” on April 26-27. The biggest party ever seen in California was to cost some $22,000 and Grif was a major contributor.[10] It included a parade to rival the fiestas and what The San Francisco Call declared as “the largest barbecue ever given on the American continent”: 1,500 pounds of beef on 16 roasting pits served by 200 waiters attending 15,000 celebrants. Some 25,000 buns and 10,000 pounds of clams topped off the free bounty, which was enjoyed after rounds of speeches by dignitaries.

The Times played heavy with the prose, calling the jubilee “the most significant and momentous (occasion) in all the prosperous years that the great Golden State has enjoyed since priceless wealth was found in her bosom”. The Herald, on the other hand, was more direct and summed it up nicely in one of its headlines: “A Flood of Eloquence and Beef”.

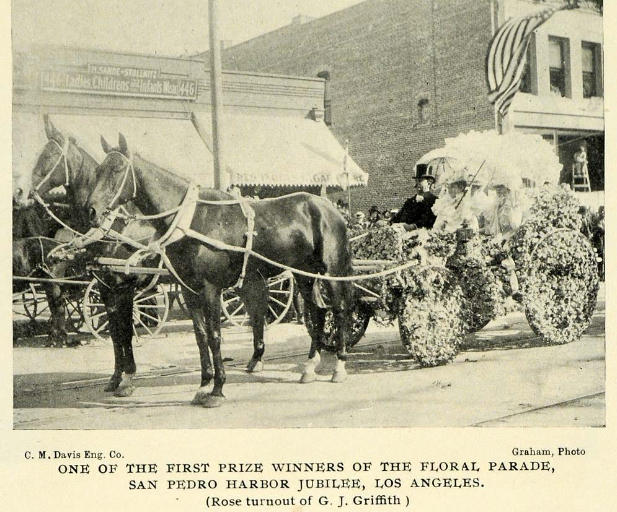

For Grif, the jubilee highlighted his reputation, as per the Times, as a “builder of cities”. He certainly cherished his roles as a member of the “Free Harbor” executive board and chair of its invitation/reception committee. Over those two jubilee days, Grif played his part well, helping regale VIPs and entering his handsome horse carriage in the flower parade, where he won first prize in his category.

Joining Grif on the carriage were Tina, the wife of Tina’s brother Joseph and a female friend of the ladies. A photo (see image at start of chapter) shows Grif sitting ramrod straight, holding the reins tight, Tina beside him.[11] “The ladies (were) attired in pink and carrying pink parasols to match the decorations of the vehicle,” the Herald reported. “Roses and carnations were used with great artistic effect and lavish profusion, producing one of the dreams of the parade.” It was a visual snapshot — the only one known to exist — of a Grif and Tina together and appearing happily married. It was either very deceiving, or a time in their marriage when stresses had yet to turn Grif into Mr. Hyde.

Hollywood, Here I Come

Grif’s ability to dabble in activities that didn’t make money, but which often required him to put up money, was thanks to the sale of Tina’s Briswalter property. Now land-reduced but cash rich — after previously being land-rich but cash-stretched — Grif did turn his sights to a project that promised new financial rewards: taking city expansion in his direction. For two decades, he had seen railway owners and their cronies profit from a scheme that kept repeating itself. They would buy large, undeveloped parcels outside the city when it was cheap, then lay lines to those areas and subdivide, luring buyers with easy access to and from downtown. Of course, the markup could be enormous, making millionaires of those railway insiders not from the rails but from buying and selling land. Grif never was one of the insiders and thus never got a real railway to lay tracks to his rancho during the decade that he tried to subdivide starting in 1888. Areas farther north from downtown, such as the fledgling Hollywood, were also not part of that early expansion.

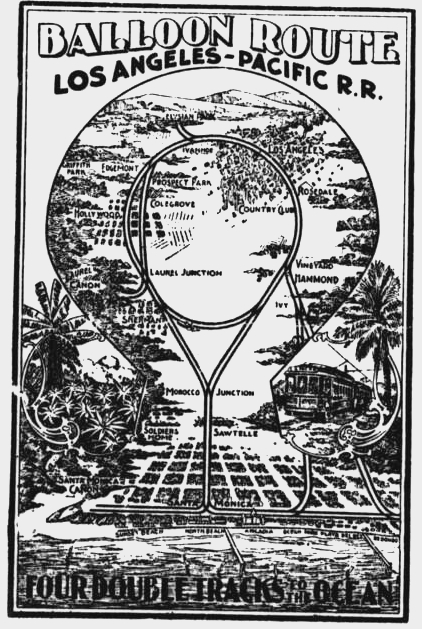

His initial approaches were determined but piecemeal. Grif helped fund the short, bare bones railway to the Ostrich Farm in 1887. It made access to the farm easier and showed off the rancho, but it didn’t sell the area as a reliable investment. Once the farm petered out in 1889, so did the line since it couldn’t compete with the more modern, and more comfortable, rail lines taking the city to the east and south. It wasn’t until 1898 that Grif saw his chance to bring a real railroad his way by partnering with his neighbors in Hollywood and, eventually, with the good developers of distant Santa Monica.

A short line through Hollywood had been bought by railway investors and Grif saw his chance to get in on the ground floor. He contributed to and helped raise $25,000 from property owners to help electrify and extend the line.[12] Grif even became a pitchman, called on to encourage other property owners to keep growing the Los Angeles-Pacific Railroad. By 1899 that included getting folks to donate rights of way for the expanding route — not as do-gooders, he insisted, but as smart investors who’d later cash in by selling land.

Speaking to owners of property along Prospect Avenue (later Hollywood Boulevard) in October 1899, Grif recalled that when he first arrived in 1882 one could buy an acre of land for $1, and now an acre could run $300-$500. Hollywood’s residents were, for the most part, farmers now but even greater rewards were around the corner, he told them. “The next crop to be harvested,” he promised, “will be the home-seekers, the intellectual people of the Eastern States, who, by their improvements, will make its lands worth not $500 but $5,000 per acre.”[13]

Mind you, turn-of-the-century Hollywood was not much of a town. It wasn’t even Hollywood, technically, but Nopalera. Hollywood was the name of the tract platted by Harvey Wilcox. In 1900, the entire area had around 500 residents, thousands of acres in barley and wheat, and hundreds of thousands of lemons harvested annually, especially for the market against scurvy. Those lemons thrived in a frostless belt along the Cahuenga Valley and in Hollywood proper. Pineapples and bananas were also grown there — creating a unique marketing angle when pitching land to Easterners tired of cold weather.

By early 1900, the rights of way were secured. For a mere $5, Grif himself sold the Los Angeles-Pacific Railroad a 35-foot-wide strip of land connecting Hollywood to the existing rail line at the city limit of Los Angeles.[14] The line continued expanding west to Santa Monica and its beautiful beaches. By 1901, the line had a Balloon Route that was a tourist sensation, advertising “10 beaches and 8 cities … 101 miles for 100 cents in 1 day.”[15]

But Grif didn’t stop with a railway. By 1901, he was a local cheerleader for what nationally was being called the “Good Roads Movement”. The cause was begun by bicyclists seeking graded roads since two wheels didn’t work well in mud and ruts. Grif saw a future around individual mobility. Sure, trains moved people around quickly, but they couldn’t take people door to door to where they wanted to be. Already, Los Angeles had a nascent “motor carriage” company and Grif himself was quick to move away from horse-drawn carriages, owning seven Studebakers in the first 20 years of the 1900s.[16]

Ever the pitchmen, Grif and partners in May 1901 organized a “Good Roads” excursion to Hollywood — ironically by train — for 300 business leaders, politicians, potential investors and newsmen.[17] Grif pitched the vision of a wide boulevard from Hollywood to downtown Los Angeles. Paving wasn’t widespread yet, so Grif even promised free gravel from his rancho to “macadamize” the road – essentially using crushed stone that is then compacted. Hollywood property owners were quick to pay for a boulevard to the limits with downtown, and within two years most of the rest was taken care of by the Los Angeles city government.

Of course, Grif’s self-interest was built into this project. Getting reliable transportation, be it by rail or road, to the rancho area was crucial. Grif had learned that the hard way in the late 1880s when he was unable to sell those 1,800 acres. With rail and road now coming along nicely, Grif and cohorts decided it was time to buy and subdivide for themselves. November 17, 1901, saw the creation of The Los Angeles Pacific Boulevard and Development Company, of which Grif was a director.[18] It brought together 100 businessmen worth a combined $60 million, according to their own publicity, making it the wealthiest investor group up to that time in Los Angeles.

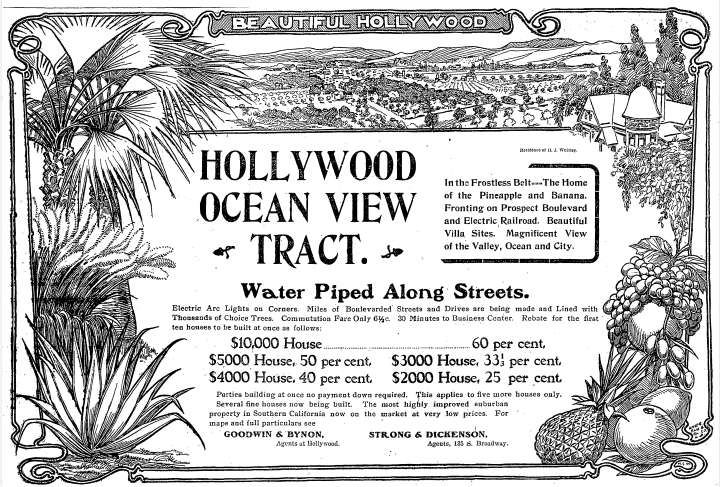

The group bought nearly 400 acres in Hollywood and, even though the sea was 11 miles away, the project became the “Hollywood Ocean View Tract”. On a clear day the higher lots did have a view of the wide Santa Monica Bay, as well as the farmed valley in between, and even views of downtown to the southwest. Per its bylaws, no home could cost less than $3,500 to build (about double what typical homes cost) and no liquor would be allowed — a concession to Hollywood’s prohibitionist founders.

Half-page newspaper ads showed an idyllic farm/hillside scene framed by palms and exotic fruit. The first words were: “In the Frostless Belt — The Home of the Pineapple and Banana”. Advertised were modern amenities like water piped along streets (i.e., not wells), electric arc lights (not dim gas lamps) on street corners, cemented curbs (not dusty pathways), and “miles of Boulevarded Streets”.

So now Grif was invested not only in subdividing part of Los Feliz but also the Ocean View Tract, and the railway he helped cobble together, which was used by the spectacularly successful Balloon Route, tied those investments together nicely. The route started downtown, and then passed through his Ivanhoe subdivision near the entrance to Los Feliz Rancho. From there, on to Hollywood and Ocean View – about 30 minutes by rail from downtown.

“The campaign was on,” Palmer wrote of the Ocean View Tract marketing, “car excursions, tallyho excursions, pep talks, free luncheons, banquets for prospective purchasers with more bouquets in evidence than could be called tangible.”[19] Entertaining well-heeled, prospective buyers was often the duty of Grif and/or H.J. Whitley, who had brought the investors together and was later dubbed “the Father of Hollywood”. It was all a bit incestuous – lots of glad handing, speeches and old boy networking. As Palmer noted, “Col. Griffith toasted Mr. Whitley, Mr. Whitley toasted Col. Griffith, the real estate agents toasted both, and ‘a good time was had by all’.”

Grif was certainly in his element, surrounded by business partners and seeing Hollywood grow before his eyes. He even had his 50th birthday extravaganza in Hollywood on January 5, 1902 – a fete that started with his entourage arriving on the “Mermaid”, the private car of Los Angeles Pacific Railway owner Moses Sherman. Ironically, it probably wasn’t even his 50th since Grif in his own biography wrote he was born in 1850, which would have made him 52. In any event, given Hollywood’s success it was a good year to celebrate 50.

Pineapples, mangoes and cherimoyas grown right there in Hollywood provided exotic desserts for the birthday party. Those toasting to Grif included Mayor Snyder. “If a man is worthy, noble — a good man — he should be honored while he lives,” Snyder said of Grif, also wishing him a life “crowned with health and prosperity, with happiness and honor.”[20] High praise from the man who was the first to publicly cut ties with Grif following Tina’s shooting.

But the tragedy was still nearly two years away and Grif in January 1902 was still climbing social and business ladders. By June, 17 miles of Hollywood boulevards were ready and another excursion brought 300 leaders to see, hear and feel the future. “Iron-shod hoofs and rubber-tired wheels chased each other almost noiselessly over the matchless roads,” the Herald reported on June 27, “the hard smooth, properly built, dustless roads that have helped make Hollywood’s fame.” Here, too, Grif had shown foresight — promoting wide, solid boulevards that were part of an envisioned culture built around cars.

Grif’s promotional work was widely acknowledged, The Times on June 27 even dubbed him “Mayor of Hollywood”. Ocean View lots were selling well, and investors were funding the Hollywood Hotel and the Bank of Hollywood. Both were considered prerequisites for potential buyers — the former to house visitors and the latter to take their deposits. Now ready to show off their work, Grif and fellow investors on May 3, 1903, invited hundreds to visit Hollywood. A brass band greeted the special guests, followed by speeches. Chosen to honor Whitley, Grif was in his element and those watching could see the pride he took in his role. “Col. Griffith in immaculate attire – Prince Albert, black tie, and boutonniere, brought his broad shoulders and portly frame to a stance,” Palmer wrote.[21] “His round, colorful countenance beamed on those about him in a broad smile of justifiable pride, while his bright black eyes twinkled from under his heavy brows and perfect coiffure. His lips parted, and from beneath his heavy, well-waxed mustache issued salutations and words of praise”.

Grif had further plans in Hollywood, Palmer noted, a resort hotel atop Olive Hill, which Grif had recently bought near Hollywood’s border with Los Angeles and situated near Eddy’s planned incline railway to the top of Griffith Peak.[22] A Hollywood-area newspaper had earlier urged Grif to turn those 36 acres, now planted with 10,000 olive trees, into a world-class resort. It didn’t outright beg, but pretty much said it was his destiny to do so and added a dollop of flattery: “Wherever he is known his public spirit and his philanthropy make glad the hearts of those who are brought in contact with him”. The writer concluded that during his 30-year friendship with Grif he “has never known him guilty of a single mean, ungentlemanly or underhanded action during all those years, nor do we believe him capable of such action.”[23]

As for the bigger picture of Grif’s rancho property, it had taken a decade, and required a railway and boulevards, but Grif was finally seeing interest in folks buying plots and moving north of downtown Los Angeles. Hollywood became the epicenter of that shift, and in August 1903 a majority of its 700 residents voted to incorporate as a city. The first law, true to its founders, was a ban on liquor sales.

Captain of Industry?

Now a capitalist and developer, Grif also began thinking about becoming an industrialist. The turn-of-the-century buzz was about bringing “manufactories” to the region. Grif was among those who could envision a Los Angeles that manufactured goods, not just farm products, or dreams for that matter. In a long, rambling essay for the 1897 book Then and Now, he explained that Los Angeles had oil, rail and soon a deep-water port to further industry and trade, especially abroad. Manufactured goods could be next, but proceed with caution, he argued. “Trade is not created, but rather is evolved by the expansion of consuming ramifications, otherwise, the enlargement of purchasing territory,” he stated with bloated prose, “therefore manufactures, in a comparatively new country like the southwest, cannot be launched into existence on a large scale at once, but instead must have small beginnings.”

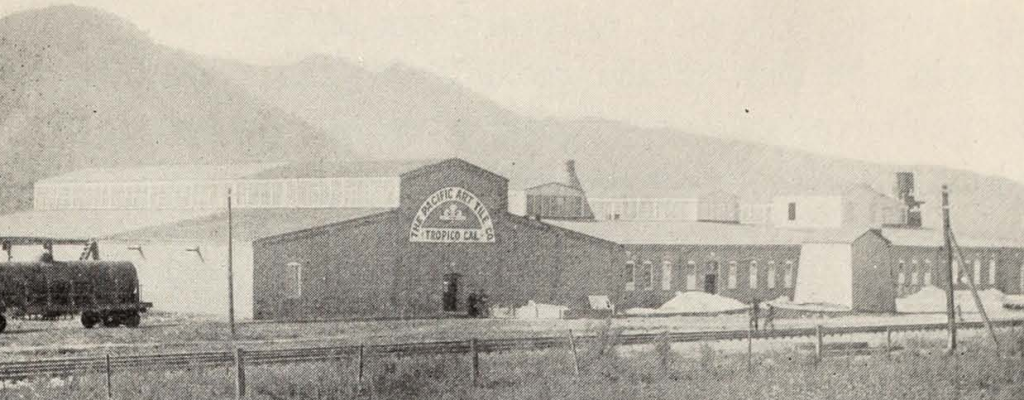

Three years later, Grif felt the time was right to put his words into practice. As the story goes, Grif, on hearing that a famous decorative tile maker was looking to set up business in San Francisco, decided to hijack the idea for Los Angeles. He wined/dined Joseph Kirkham, who had been with Wedgewood in England, and donated 22 acres for the factory site in Tropico, a town just east of the rancho and today is part of Glendale. Grif became president of the Pacific Art Tile Company, which started with $600,000 in capital and also drew investors from back east.[24]

In March 1900, the investors announced plans to hire 800 workers for the “largest manufacturing enterprise the region has ever had,” according to the Herald. So much for Grif’s go-slow advice. The enterprise was billed as progressive by industry standards back then. “There will be no smoke or offensive vapors to contaminate the neighborhood,” the Herald reported, and one area will be open for “ladies who desire to do (clay) modeling of their own, or color, decorate or glaze their own work.” A third of the jobs were expected to go to women, “furnishing pleasant and profitable employment to young people of both sexes.” The Times noted that “it will not be the policy of the factory to employ very young boys or girls” and that “much of the work will be of such a nature that it will not require a change of clothing to do their jobs.”[25]

Over the next two years, Grif would periodically update local businessmen, host potential investors, and get some press coverage like the Herald’s “Progress of Our Manufactories” — a full-page review on December 23, 1900, in which Pacific Art Tile got top billing. But it took all that time just to get to a groundbreaking ceremony on July 25, 1902, and, for reasons unknown, Grif was now no longer president, just one of several directors.

The grand opening followed more than a year later. To Grif’s credit, it did have the effect of renewing excitement for the industrial future of Los Angeles. On August 1, 1903, 400 Chamber of Commerce members and spouses arrived by rail from downtown. Some 500 locals were also there to celebrate the opening of the $250,000 main building, the only “manufactory” of its kind west of Indianapolis.

Several dignitaries spoke, including a Chamber of Commerce official and a “temperance evangelist” famous for getting millions across the country to sign an alcohol abstention pledge. He “did not refrain from taking a shot at his arch-enemy, the booze demon,” the Times noted, ironic given that Grif just a month later would have his own booze demon to reckon with.

Grif told those gathered that local markets and clay supplies would be plentiful, and that the savings of not having to ship ceramic tiles from the East Coast would be enormous. “Business statistics show that more than 1,500,000 square feet of floor and wall tiles are annually consumed on the Pacific Coast,” he cited, “and if we could turn out 1,000,000 square feet per year, which is about our present capacity, we should not then supply more than one-half of our home demand in the immediate future.”

Other products can also be made “from our extensive beds of clay,” he added. “There is an enormous consumption of what is called sanitary ware, used by plumbers in all modern residences and public buildings, on this Coast, and as these goods are very heavy, the freight is a very large part of their cost … The erection of another factory building for this purpose is contemplated at an early date.”

And then, of course, there was the prospect of even bigger markets in Asia and India now that Los Angeles had a deep-water port. The sense of industrial destiny was all the greater after President Roosevelt’s visit a few months earlier, when he praised the region’s potential to reach across the Pacific Ocean.

Relishing his duty to dedicate the plant, Grif extolled this “new industry” and, to his credit, the opportunities each worker now had. “There is another consideration which will have weight in the minds of all those within the sound of my voice.” That would be workers with steady, well-paid jobs, he said, “enabling them to earn a livelihood for themselves and their families and consequently the planting of new homes and promoting a healthy and permanent growth of the community.”

Grif sounded like a proud father showing off his family. “Realizing that our employees must have homes,” he added, “and desiring that they shall be pleasantly situated, the directors have set aside a considerable tract of land, which will be traversed by broad, shaded streets, and furnish sites for 200 residences and cottages.”

But as fate would have it, August 1, 1903, did not turn out to be the birthdate of a successful manufactory. The local demand was there, but Pacific Art Tile’s troubles had started with that three-year gap before its grand opening, followed by a long delay in getting key equipment. And then it turned out that good quality clay deposits were actually farther away and more expensive than first thought. Within a year the company had been sold to other investors and renamed Western Art Tile.[26]

August 1, 1903, did, however, turn out to be Grif’s peak of achievement. Up until now he had lived the American Dream: poor immigrant, journalist, mine speculator, rancher, financier, developer and presently captain of industry. But four weeks later it would all come tumbling down at the Hotel Arcadia in Santa Monica.

- Atchison and Eshelman, Los Angeles: Then and Now, pp32-34 and pp116-120. ↵

- Kevin Starr, Inventing the Dream, pp64-65. ↵

- Edwin Palmer, History of Hollywood, p99. ↵

- Herald, March 2, 1897; Times, March 21, 1897; Times, July 17, 1898; Times, December 16, 1898. ↵

- Herald, September 2, 1900. ↵

- Times, January 22, 1896. ↵

- The Capital, October 5, 1901. ↵

- Griffith Family Papers; from the list of property conveyances prepared by Griffith's legal team for his divorce proceedings. ↵

- Herald, September 23, 1900; September 13, 1900; Herald, May 14, 1901;Times, February 27, 1901; Herald, May 20, 1903. ↵

- Grif's contribution was among the donations listed in a 1912 pamphlet announcing his gift of a Griffith Park observatory. ↵

- The photo, given how it contains a caption and photographer info, appears to have been part of a publication or postcard from the event. It was located at periodpaper.com, a website selling historic images, and no other copies have been located. ↵

- Palmer, p92. ↵

- Herald, October 8, 1899. ↵

- Griffith Family Papers; from the list of "conveyances" prepared by Griffith's legal team for his divorce proceedings. ↵

- Trolleys to the Surf by Ira Swett and William Myers offers an excellent account of early rail activity in Los Angeles, especially the Balloon Route. ↵

- Grif provided a testimonial for a Studebaker ad in the Times on June 28, 1914. ↵

- Herald, May 26, 1901. ↵

- Palmer, pp113-114. ↵

- Palmer, pp114-115. ↵

- Herald, January 5, 1902. ↵

- Palmer, p116. ↵

- Grif later had to sell Olive Hill to come up with cash for his divorce settlement, and the property was sold several times before being donated to the city for today's Barnsdall Park. ↵

- Cahuenga Valley Sentinel, March 24, 1900. ↵

- Herald, August 15 and December 23, 1900, and Times, July 8, 1900. ↵

- Times, July 8, 1900. ↵

- Bulletin of the American Ceramic Society, May 1943, p148; see also https://sandiegohistory.org/journal/1999/october/china/. ↵