16 Ambition to Achieve

“No man is entitled to honor and respect for what he possesses – only for what he achieves, and it is my ambition to achieve as much as lies within my gifts and my resources for my city and for my fellows.”

“I am sure that others who know under what trying circumstances I have struggled, will be inspired by my ability to rise above my handicaps and environment.”

—Excerpts from Grif’s letter on December 21, 1912, donating $100,000 for a Griffith Park observatory and hall of science

When Grif emerged from San Quentin on December 3, 1906, he returned to a very different Los Angeles. Less than three years had passed since his conviction, but the city had matured from awkward teen to confident young adult. Hollywood was growing as Angelenos finally set their sights on property north of downtown; the new San Pedro port would soon benefit from the under-construction Panama Canal; and it seemed the city had even solved its water problem when voters approved bonds to build the Los Angeles Aqueduct, then the largest water project ever attempted worldwide.

Local politics, too, were maturing. For years, Teddy Roosevelt had inspired others across the country to take on the political machines that controlled cities. Those “machines” were often fed by railway company donations, and in the case of Los Angeles, in fact all of California, it was the Southern Pacific railroad, aka The Octopus, that was seen to run politics. Progressives like Grif were too early when they tried at the turn of the century to rein in the rail rogues. But in 1907 a new crop of local Progressives started a Good Government movement that pushed through reforms to democratize city elections and finally enforce a recent law allowing voters to recall elected officials.

Some business titans opposed the group since too much reform was not in their financial interests even if they, too, had issues with The Octopus. Grif, on the other hand, was optimistic that this time political reform would stick and would benefit Los Angeles, especially Griffith Park. In 1909, Mayor Arthur Harper resigned rather than face what would have been the first mayoral recall in U.S. history, and by the end of that year voters had secured a Good Government slate across City Hall. “For the first time in American history,” a historian would write decades later, “the forces for municipal reform in a major American city had united … to thoroughly defeat a political machine; the results were overwhelming and impressive.”[1]

This new Good Government movement aimed to clean up politics and Grif positioned himself to be part of it, at least in terms of Griffith Park, by publishing in 1910 Parks, Boulevards and Playgrounds. Grif had previously focused on statewide and national prison reform but saw that local political reform could help him secure what he long wanted as his primary legacy: the Griffith Park of his dreams. It might also complete the path to redemption that his prison reform campaign had set him on.

Like other cities across the country, Grif wrote, Los Angeles “has been the plaything of a political machine owned body and soul by the railroad and other interests”.[2] Finally, he said of the 1909 election results, “we have somewhat shaken off the shackles”. He was incensed not just with the Southern Pacific but also with the Pacific Electric Railway, the suburban trolley line owned by Henry Huntington. They were a rail oligarchy that determined where public transit would go, and thus which areas would flourish. The Free Harbor fight a decade earlier reflected that tension with transit titans, and Grif had complained even earlier, ever since he tried to develop the southern section of his rancho, only to find the city expanding in the other direction thanks to railway decisions.

With Griffith Park, he saw the same danger. What good is a magnificent park, Grif fumed, if no public transit brings the masses in? Remember this was before the city’s car culture, so the vast majority of residents were still dependent on public transit to travel any distance. “Today, this city is rapidly approaching the 400,000 mark; it has gathered Griffith Park within its limits; but not one single step has been taken to secure that accessibility without which the park cannot be considered as open equally to both rich and poor,” Grif wrote.[3] Unless one has an automobile, “the park is non-existent for the poor man” because getting to the picnic grounds would require a two-mile walk.

Now, he hoped, City Hall could make decisions based on what benefited the public, not oligarchs. “At last there is a prospect of Los Angeles no longer neglecting the invaluable asset those in control of her affairs have scorned so long,” Grif wrote.[4]

Selling Safety Valves, not Eugenics

It had been nearly eight years since Grif staged his last public campaign to improve Griffith Park, so he used the book to familiarize the new breed of city officials with the problems he had found in the early 1900s: the illegal logging of trees; horses and cattle grazing on park land; little security; and complete disinterest on the part of city fathers to do anything about it. Photos of fallen trees and grazing animals made a visual impact that his earlier campaign, which focused on newspaper articles, could not.

Besides listing those problems, the book also reflected Grif’s conviction, foresight and philosophy that parks are crucial to a healthy society. His very first point: America’s population was quickly shifting from rural to urban and, while cities have wealth, “they are also hotbeds of disease, poverty, vice and indescribable misery.” His goal with Griffith Park was to provide “an outlet for the swarming population of the future” — and he had no doubt Los Angeles would continue to grow and face those social pressures.[5]

Grif was emphatic: “Public parks are the safety valves of cities.”[6] Those who have built grand park systems in other cities know “that there must be an outlet for the population that chokes the streets and alleys of our cities; that fresh air, communion with nature and amusements other than those afforded by the cheap theatre, moving picture show or saloon, are requisites to public health, and worth spending money on”.[7]

A “City Beautiful movement” gaining traction nationwide championed the same views, and a leading local promoter cited Grif as an example of the new “Socialized Capitalists” — men like Andrew Carnegie who give “not so much to aid individuals as to better social conditions, or even to transform society itself.” These men, the Rev. Dana Bartlett wrote in his book The Better Way, were becoming “Captains of Philanthropy where they were once Captains of Industry.”[8] As for what to donate, Bartlett was convinced “no better donation can be made than in furnishing a large number of ‘breathing places’ easily accessible to all the people.”[9]

Many a philanthropist of the day would have taken the next step of dealing with this “swarming population” by embracing eugenics – the notion that biology shapes behavior and that sterilization of the weakest, poorest segments can improve the whole of society. But not Grif. He brought it up in his book only to shoot it down with his conviction that perfecting the masses requires “elevating their standard of life.” After citing a contemporary expert who denounced the biological premise, Grif wrote that his own experience convinced him that socio-economic improvements, not sterilization, were required. “I believe that no child should be compelled to live in congested tenements; that every child has a right to space, plenty of God’s sunlight and fresh air; and that, however poor its parents may be, it should have proper food and treatment.”[10]

Well-kept parks, playgrounds and even boulevards can play a big role in improving socio-economic conditions, Grif noted, but often public officials don’t appreciate that or, where there is an open space, they restrict public access. Park administrators still “cling fatuously to the old and autocratic theory that the people are to be distrusted, that their own use of their property is a privilege and not a right; and that, as such, it must be fenced in by innumerable restrictions” that impose “on the holiday seeker the very constraints he left the city to avoid.”[11]

Grif also envisioned a day when the “possibilities of recreation unknown to our fathers are placed within the reach of millions of our people.” The private transit of bicycles, motorcycles and automobiles would guarantee that, he was sure, but for now the public transit of railways and trolleys still dictated how people got around and that usually wasn’t developed in the public interest. “There is more, much more money, for the railroad companies in carrying passengers to distant points,” Grif noted in describing how the city came to sprawl thanks to rail decisions. “But in this gain to them there is a loss to the city, in health, happiness and contentment, that dollars cannot measure.”[12]

Grif was describing his hoped-for, big-picture legacy: a Los Angeles transformed, improved, even perfected by his park. In stark contrast to the egomaniac portrayed at his trial, here one could see an enlightened visionary: embracing democracy over a political elite; aware that the rural to urban transformation of the United States was reshaping society; touting parks as safety valves and to save young lives; anticipating a new boom of immigrants as the globe shrank, especially with the upcoming Panama Canal.

A Real Park Emerges

To attain this vision, Grif wrote, city fathers must regulate transit lines and staff departments with professional, non-political planners. The Los Angeles of 1910 was starting to look like that, and decisions were finally starting to benefit Griffith Park. The city had annexed Griffith Park on February 27 and by October five miles of gravel roads inside the park had been built by a crew of 40 men; the park superintendent started plans for a zoo; and fishermen were treated to 5,000 rainbow trout placed along the park’s stretch of the Los Angeles River. Within a year, nearly nine miles of roads were in, and a new proposal was on the table: a golf course.[13]

The City Hall run by the Good Government slate, and headed by Mayor George Alexander, was having an impact. “For the first time,” the Herald reported on May 28, 1911, the city had a Board of Park Commissioners that knew what it was doing. The previous commissioners, it insisted, were politicians who “did not know a park from a picket fence” and ran a parks system that “suffered for years from a criminal system of negligence, incompetency and mistaken policy.” If the city funds the system properly, the Herald boasted, it “will be one of the show places of the western world.”

Fifteen years after it was donated, Griffith Park was finally becoming the centerpiece of that system.[14] Its stature had increased thanks to the recent improvements — and soon Grif’s son, Van, would add to that with a hobby that had made him a local daredevil. Since 1909, he had been experimenting with flying machines — including a glider pulled by an automobile in front of his home. Alas, the aircraft flipped and Van broke several ribs. Undeterred, within two years Van was secretary of the Aero Club of America’s local chapter and was helping pioneer a new industry. Having convinced dad to go along, the 23-year-old Van on January 11, 1912, leased 180 acres of the family property still within the rancho for a Griffith Aviation Park. Over the next five years, Van would manage the field, live there with his wife, and help launch what would become Southern California’s aviation industry. Famed aviator and aircraft maker Glenn L. Martin spent time there, teaching other future pioneers like Bill Boeing and Donald Douglas and later building planes for the U.S. military. Hollywood, too, came calling with Mary Pickford among the first actors who filmed on location there — in her case, getting on a flying machine for the first time.[15]

A Second Christmas Gift

Grif was in pretty good spirits now, seeing progress and knowing that his son had a stake in the park, too. So when December 1912 came around he decided it was time for “another Christmas gift” — pledging $100,000 (a relative cost today of $20 million) to build an observatory and hall of science that would crown his park donation 16 years earlier. These would not be academic towers but admission-free palaces for the public to observe the stars and be inspired by scientific discoveries.

It felt like old times. Grif set up a “surprise” announcement at City Hall on December 21 and was joined by a Chamber of Commerce entourage, just as in 1896. He was welcomed by Mayor Alexander and the City Council as a home-town hero, not an ex-con. In fact, not a word was printed in the Times or Herald about his time behind bars. The Times headline on Page 1 said it all:

SPLENDID GIFT TO THE CITY

The Herald included a large photo of Grif depositing his donation letter into a Christmas stocking held by Mayor Alexander.

To be sure, the entourage and the staged Christmas stocking photo all seemed self-serving, but the donation letter prepared by Grif does read like it was conceived with a deep conviction. Much longer than the park donation letter of 1896, it explained his motivations and was read aloud by the city clerk. It began:

“Sometimes I ask myself, ‘What have I done to perpetuate the posterity of my city in perpetuity?’ I feel it is my duty as a good citizen to contribute to the utmost of my means and powers to the common good – to lift myself above selfishness, to render service as well as accept it.”

He then directed advice to his fellow capitalists:

“Too many of us are planning and scheming for private advantage and personal profit; too many of us are sacrificing patriotism for profit; too many of us are too concerned with ourselves, the interest table, the market reports and our particular specialties to trouble about the community. Our ideas are far superior to our ideals. We must remember that our strength as individuals is only in proportion to our community strength and that we can only really advance ourselves by advancing the interests of the people at large.”

He even hinted that his ambition to achieve the park, observatory and hall of science might some day provide the honor, respect and even redemption that he so longed for from his fellow Angelenos, especially after his humiliating trial.

“No man is entitled to honor and respect for what he possesses – only for what he achieves, and it is my ambition to achieve as much as lies within my gifts and my resources for my city and for my fellows.”

“It is not what I plan or what I do that will mean most, it is my example that will benefit Los Angeles most, for I am sure that others who know under what trying circumstances I have struggled, will be inspired by my ability to rise above my handicaps and environment.”

Grif never explained why he chose an observatory, but he appeared to have had an epiphany during a visit to the telescope atop nearby Mount Wilson. “The experience moved him profoundly — a distant, heavenly body suddenly being brought so close and made so real,” local politico John Anson Ford recalled years later.[16]

Grif did write that he hoped an observatory atop the park’s highest peak would:

“inspire men with hope and dreams. Ambition must have broad spaces and mighty distances. From this noble height one may behold the glories of the fairest land God gave to his children, and no man standing so near the stars, with illimitable fields and seas to challenge him to the utmost, can dare doubt or despair of future opportunities.”

Grif then circled back to the park itself and echoed his overarching philosophy stated in his parks book:

“Public parks are a safety valve of great cities and should be made accessible and attractive, where neither race, creed nor color could be excluded. Crime and degeneracy can best be battled with by pleasure grounds.”

“Give nature a chance to do her good work and nature will give every person a greater opportunity in health, strength, and mental power.”

The City Council unanimously accepted Grif’s latest gift, and Grif presented a letter from the Pacific Electric Railway stating that, once construction was underway, it would run a line into the park. Grif said he expected it to cost just 5 cents a ride — as per his stipulation in 1896.

He later commemorated the event by publishing “Los Angeles Christmas Present” — an eight-page pamphlet whose cover was mostly a photo portrait of a dapper Grif, looking just as in his heyday. The caption read, in part: “time has dealt very kindly with the Colonel during the past sixteen years.” The contents included: his two donation letters; the City Council approval of each; a list of the 47 community leaders who attended the latest donation; and nearly three pages of praise from Southern California’s pre-eminent astronomer, Edgar Larkin, director of the Mount Lowe Observatory near Pasadena. The last page was an article by an old friend listing many of Grif’s good deeds under the headline “His Reward”.

Anyone reading the pamphlet back then would have been thinking: There he goes again, letting his ego get in the way of his philanthropy. As such, the proposed donation only left an even bitterer taste in the mouths of some Angelenos still raw from Grif’s past. The Graphic, which had embraced the prison-reform Grif, called it “a flamboyant attempt at rehabilitation not to be approved.”[17]

In a letter published by the Examiner, a noted lawyer wrote to the City Council “to repudiate your vote of thanks and protest the acceptance of the gift.”[18]

The Examiner two days later published a second letter to the City Council, this time on its front page, and asked readers to send in their thoughts. The second writer went straight at Grif: “The man’s colossal impudence is overlooked, his famous crime is condoned and his brazen effrontery is treated as a laudable benevolence because he is a millionaire.”

“On behalf of this rising generation of boys and girls we protest against the acceptance of this bribe,” he added. “Are you prepared to say to them that if a man is a millionaire he can commit a crime, and then with his wealth bribe the community to receive him back into fellowship merely because of that bribe?”

Still, others came to Grif’s defense — some noting his sobriety, others preaching forgiveness, and one arguing that Grif’s money was cleaner than that of Carnegie’s. Of the 15 letters published in the Examiner, only four were strongly anti-Griffith.

Nearly a Greek Tragedy

As far as Grif was concerned, he was again an upstanding citizen, and his swagger started to show. He ignored a Park Commission request that his $100,000 gift instead go to build a recreation center in the park, and personally wrote to vendors inquiring about the latest telescopes and cameras for a motion picture viewing area.[19]

Grif frequently visited the park, especially the expanding zoo, and later funded a private bus line that only charged his 5-cent fare and was run by son Van.[20]

Grif also quickly took control of another idea brewing for the park: a Greek-style ampitheater. The East Hollywood Improvement Association pitched the idea to Grif, and he quickly signed on. By May 1913 the Park Commission had the proposal on its agenda[21], but Grif made sure he was seen as the driving force — a tactic that would nearly derail his redemption train. In June, he addressed several hundred who gathered in Griffith Park to lobby for the theater,[22] and within a week had contacted an architect to make plans. [23]

The Graphic, again, lambasted Grif, saying “the self-advertising is out of all proportion to the benefits to be derived by Los Angeles” and later criticizing “the colonel’s insatiable appetite for publicity.” As for the proposed theater design, the weekly noted, it looked like a “hybrid between a soup ladel and a coal shovel.”[24]

But the Times and Herald were on board. On October 11, a day after Grif toured the proposed site with architects, the Times reported that the mayor, City Council AND the Park Commission were “thoroughly satisfied”. It followed up a day later with a Sunday feature headlined:

STATELY STADIUM IN SETTING OF GREEN

A large photo showed Grif signaling to his VIPs features of the outdoor area, and the article talked of a 50,000-seat venue. A second article written by the city’s most renowned artistic manager, a man who had visited every major amphitheater in the world, vowed Griffith’s Greek Theater would be “rivaled only by the Colosseum at Rome and the Temple at Athens.” The city should “cooperate” with Griffith, wrote Lynden Behymer, since the venue would allow “the masses and the classes” to mix, and it would help create a Griffith Park that is “a veritable Garden of Eden for the education, amusement, and the resting of tired bodies and minds.”

When December 1913 came around, Grif was again in the Christmas mood and announced he would put up $50,000 for the theater as well as increase his observatory donation to $150,000. He followed that up in January with a formal letter stating two conditions for both donations: Grif would hire the architects, with city approval, and a three-person commission would manage the projects.

The mayor and City Council had no problem with the terms, but feathers were already ruffling on the park board. So instead of getting the board’s sign-off, the City Council sought and got support from the city’s Public Works Commission, which ironically was chaired by the city’s first (and so far only) Socialist Party council member, Fred Wheeler. On this — the idea of more jobs (Wheeler was also a union leader) and a grand public park for all — socialist Wheeler and capitalist Griffith were allied.

No sooner was the certificate creating Griffith’s commission minted in May 1914, than the park board sued to overturn – arguing it alone had jurisdiction over which park projects to undertake, as well as how and where. The Graphic agreed, writing on June 20 that this new commission would only create “friction and folly” and set a precedent whereby “there is no telling what freak things will be done to our public parks.”

In July, the park board played a new card: vowing to resign en masse. Wheeler came to Grif’s defense. “The attack on Griffith’s donation has been a personal attack on Griffith,” he shot back. “If he has committed any error in his time he has paid the penalty and paid in full.”[25]

For months the bickering continued, and the lawsuit slogged through the courts — until the City Council, knowing that a special election was coming up, figured: Ask voters if the council acted correctly. The Times was among those calling for a “yes” vote, lamenting “the vanity of the Park Commissioners”. The question was among seven propositions on June 1, 1915, and public sentiment was very clear: 49,057 backed Grif; 10,862 backed the park board.[26]

That didn’t convince the board, which noted that the city’s own charter, or set of organizing principles, barred a private individual from making decisions on public land. What to do? Well, as it happened another special election, this time to amend the city charter, was being prepared, and so the Chamber of Commerce secured a proposed amendment to allow a special committee when a donor to a park project wanted to control spending of that donation. Of the 16 proposed amendments, it was not the most talked about (that honor belonged to the issue of whether to allow dancing in restaurants!), but it proved to be the most contentious. This time, it faced opposition from the Municipal League, which saw it as undermining good government. The result on October 24, 1916, was much closer: 24,111 for the amendment; 23,119 against.[27]

Grif, the City Council and his chief ally Wheeler had won the battle, but oh how close they came to defeat. Imagine if they had lost: It’s quite possible Grif would never have put up the funds to build the observatory or theater. That scenario would have been more likely especially since the California Supreme Court in March 1918 finally settled the lawsuit by siding with the park board. Unfortunately for the board, the charter change made the ruling moot since now the City Council had explicit authorization to create a special committee.

A Will for the Ages

A few months before the charter amendment, when things looked grim for Grif, he decided to have a backup plan in case the delays went on after he did. So, on February 8, 1916, he prepared a will that increased his theater donation to $100,000 and, more importantly, stipulated that, should he die before either or both projects were completed, a three-member trustee committee would disburse estate funds and monitor progress. Grif even named who would be on it, two close friends and son Van.[28]

Grif was right about those delays — he did not live to see either project — but Van made it his mission to do so. The Greek Theater opened on September 25, 1930; the Griffith Observatory on May 15, 1935.[29]

The theater had to be scaled down due to costs, while the observatory retained most of the features sought by Grif, including a cement construction “to endure for ages,” as he had contemplated in 1912. One significant change to the observatory: it could not be built on Mount Hollywood due to its size, so it was located slightly lower.

Grif dabbled in both projects until July 6, 1919, when he died in peace and without further scandal. It should be noted that he never had a run-in with Tina or any other altercation, at least in public, in all the 16 years after the shooting. It’s also probable he never again was drunk in public — he rarely attended social functions and no mention was ever made in the press of any unbecoming behavior.

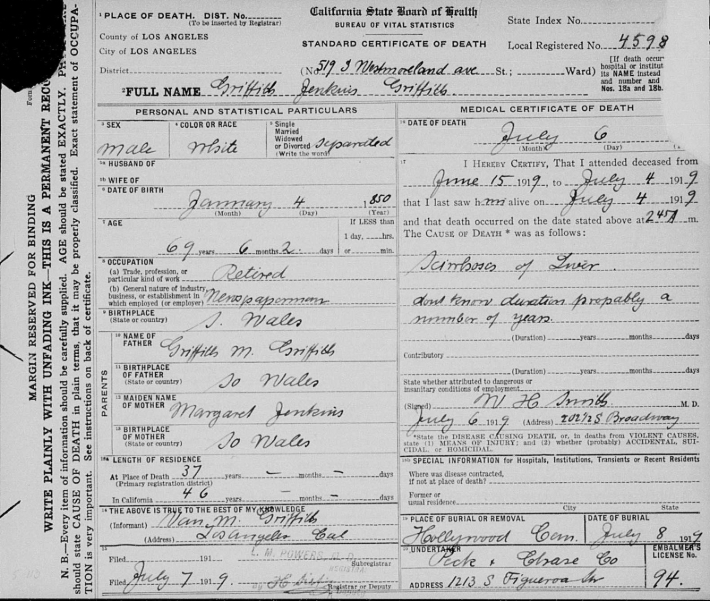

The death certificate (see below), completed and signed by Van, offered some final insights about the complicated Griffith Jenkins Griffith:

Profession: “Newspaperman”

(not capitalist, developer or even philanthropist; Van himself worked for a spell as a journalist so perhaps he wanted to remember his father’s early days)

Age: “69”

(this dates his birth to 1850, not a few years later as Grif would sometimes suggest)

Marital status: “separated”

(perhaps Van or even Tina, who lived for another 29 years, never wanted to acknowledge the finality of divorce)

Cause of death: “psirrosis of the liver”

(the alcohol that had helped ruin Grif’s American Dream took his life nearly 16 years later).

In his will, Grif left $100,000 to “my beloved son” Van, $10,000 each for 12 relatives in Los Angeles and Pennsylvania (his mother’s side of the family), $1,000 each for another 12 relatives and the rest, around $1 million, to the Griffith Park Trust Fund.

But if Griffith Jenkins Griffith expected to die a fully redeemed citizen of Los Angeles and a favorite son, he would have been disappointed. His death was reported widely — his philanthropy was recognized while his crime was mostly ignored (as was Tina) — but there were no outpourings of public grief or appreciation.

The burial service at the Hollywood Cemetery’s Griffith Lawn on July 8 was attended by just a few people, but his pallbearers did reflect the generation of Angelenos who, like Grif, had helped turn a scrappy town into the biggest city on the West Coast, and a soon-to-be global cultural magnet.

Who’s Who of Grif’s Pallbearers

Harry Chandler: The publisher of the Times, having taken over from father-in-law Harrison Gray Otis, he had arrived in Los Angeles just like Grif in 1882. Unlike Grif he always kept a low profile and was now the wealthiest person in the city, having created a vast real estate empire thanks to the Los Angeles Aqueduct.

John T. Jones: Grif’s personal lawyer was also one of his oldest friends and backed up Earl Rogers in Grif’s 1904 trial. True to Grif’s ability to cross political lines, Jones was a Democrat. Grif also named Jones, along with Van and an auditor, to run the Griffith trust.

George Rice: the loyal friend who, in the 1912 observatory donation pamphlet, described Grif as one of the city’s “wheel horses”. He had also testified in Grif’s defense at trial, saying that when both were on the Park Commission, Grif went “bug-house” every time the topic of Catholics came up.

Meredith Snyder: as mayor in 1896, he had joyously accepted the park donation. But he was also the mayor who quickly had Grif booted off the Park Commission and who cast the tie-breaking vote to formally name the park’s highest point Mount Hollywood, not Griffith Peak.

Charles Toll: a leading banker who lived in Glendale, near Grif’s ill-fated Pacific Art Tile Company. Both Republicans, they were also Chamber of Commerce stalwarts who helped win the Free Harbor battle.

Frank Wiggins: A Chamber of Commerce staffer for 34 years, he was known as the marketer-in-chief of Los Angeles as “The Land of Sunshine”. The only way to keep Los Angeles from growing further, William Mulholland once joked, would be to kill off Frank Wiggins.

And so Grif’s peers laid him to rest on July 8, 1919, with none of the pomp and circumstance of a home-town hero. What the reverend said was lost to time as no newspaper reported his words. Having moved on to other dramas, the Examiner, Times and Herald ran just a few paragraphs on inside pages. “Simple Ceremony” was the Times headline for its one-paragraph finale. Its secondary headline only reinforced the lack of interest: “Short Unostentatious is Funeral Service for Col. Griffith”.

- Mark Stevens, "The Road to Reform", Southern California Quarterly, 2004, Issues 3, 4, p362. ↵

- Prison Reform League, Parks, Boulevards and Playgrounds, p41. ↵

- Ibid, p39. ↵

- Ibid, p41. ↵

- Ibid, p1. ↵

- Ibid, pp21-22. ↵

- Ibid, p5. ↵

- Dana Bartlett, The Better Way, pp1-12. ↵

- Greg Hise and William Deverell, in Eden by Design, pp16-17, credit Grif and Bartlett with Los Angeles' initial steps towards planned urban public spaces. ↵

- Parks, Boulevards and Playgrounds, pp17-19. ↵

- Ibid, pp23-24. ↵

- Ibid, p44. ↵

- Herald, October 11, 1910. ↵

- Even a small zoo was eventually started in 1912, but not using the Los Angeles Zoological Society's proposal for a vast complex that would include "families of some of our fast disappearing aboriginal tribes". Grif never embraced that plan, perhaps because the society's president was Charles Silent, one of his lawyers who sued him after his trial. ↵

- Hunter Hollins, "Science and Military Influences on the Ascent of Aerospace Development in Southern California", Southern California Quarterly, Winter 2014, pp381-383. ↵

- John Anson Ford, Honest Politics My Theme, p124. ↵

- Graphic, December 28, 1912. ↵

- Examiner, December 24, 1912. ↵

- Herald, February 6, 1913. ↵

- Herald, May 7, 1915. ↵

- Times, May 18, 1913. ↵

- Express, June 20, 1913. ↵

- Mike Eberts in Griffith Park, p103, ties Grif's pledge to his speech on June 21, 1913, but Van Griffith, in a Griffith Family Papers manuscript titled "Greek Theater History", states the pitch happened at the group's previous annual picnic in June 2012. ↵

- Graphic, June 28 and October 18, 1913. ↵

- Times, July 22, 1914. ↵

- Herald, June 2, 1915. ↵

- Herald, October 26, 1916. ↵

- See Eberts in Griffith Park, pp106-107, for details. ↵

- Eberts in Griffith Park dedicates full chapters to the construction of the observatory, pp89-101, and theater, pp103-110. ↵