8 The Prince of Parks

1896 to 1903

_____________

“Recognizing the duty which one who has acquired some little wealth owes to the community in which he has prospered … I am impelled to make an offer, the acceptance of which by yourselves, acting for the people, I believe will be a source of enjoyment and pride to my fellows and add a charm to our beloved city.”

— Griffith J. Griffith in his (long-winded) letter to the Mayor and City Council on December 16, 1896

With exceptions for popular presidents and victorious generals, beloved public legacies are hard to come by. There’s the explorer whose name is on a bay or peak, the pioneer whose name is tied to a town, the multimillionaire who funds a university building in his name. And then there’s Griffith Jenkins Griffith, in a category all his own. Not before, or since, has the donation of so much land for a city park been attributed to a single person. So it was no surprise that Los Angeles gladly named it after such a unique benefactor.

Billed by Grif, and then echoed by the press and others, as the largest city park in the world, it was massive at 3,015.4 acres, about five square miles. That’s four times larger than New York’s Central Park — which was acquired by the city not by donation but using eminent domain to seize property. And Griffith Park provided a contrast to the mostly flat Los Angeles: a hillside with seven peaks over 1,000 feet, a fertile farm belt and a valuable five-mile stretch along the Los Angeles River.

The gift was meant to be the biggest legacy created by Grif — the poor Welsh lad who came to America and made his own fortune, and then then married into another. And he was by no means quiet in announcing his donation. A special City Council meeting was set up for December 16, 1896, but no details were released ahead of time. Grif arrived with an entourage reflecting his standing among the Los Angeles elite: three judges, two retired military officers, a lumber baron, a land developer and a textile industrialist. Building up the suspense, Grif handed a rolled-up piece of paper to outgoing Mayor Frank Rader, stating only: “This document has been tied with a blue ribbon by my better half. There goes with it the blessing of my little family.” A sweet touch, perhaps, but also the only hint of public recognition that Grif ever gave Tina for the donation.

The city clerk then read the document aloud. In it, Grif describes some qualities that weren’t widely known about him. First, he stated it was a “duty” to give back to the city that had rewarded him. (A day earlier, in enticing the press to attend, he told a Times reporter that he had a gift for the city that he hoped others with resources would emulate.) Second, like most of his peers he believed Los Angeles was destined to be a “great metropolis”, but he went further by envisioning that it would also require great public parks. Those are, he wrote, “the most desirable feature of all cities which have them”. Most importantly, he wanted those 3,015.4 acres to be “the people’s recreation grounds” and to that effect his only stipulation was that any transportation line going into the park not charge more than 5 cents per person.

Grif also conceded a selfish reason for making this “Christmas gift” while “in the full vigor of life.” And that was to see his fellow Angelenos enjoying the park. The idea being, he wrote, to “bear with me, when I cross the clouded river, the pleasing knowledge of the fruition of a wish long dear to me.”

As for a park name, Grif did not state a requirement in his letter, but the city’s own ordinance accepting the land expressed that “as evidence of the appreciation of the people of the City of Los Angeles, said park shall be forever known as and called Griffith Park.”

Ulterior motives?

So that’s how the donation was presented. But there is a back story involving the why.

It didn’t take long for some to question Grif’s motives — was he trying to unload hilly, unusable land that he had to pay taxes on? The son of a park commissioner later said his father had given Grif the idea to do just that.[1] And the man who had been Grif’s private secretary provided his own version when on trial in 1897 for allegedly embezzling from Grif’s bank account. Grif had wanted to benefit from a donation in two ways, Rhenodyne A. Bird testified: avoid a $1,600 property tax and also buy land around his rancho before the donation so as to benefit over time from the park’s attraction.[2]

The entire Bird trial was a nasty bit of publicity for Grif. Bird insisted Grif had paid out $10,000 to newspapers to publish articles praising the park donation as well as flattering biographies of Grif — all allegedly written by Bird.[3] He also described Grif as exhibiting “insufferable self-pride and conceit” and as a drunk who slept off his binges at the office three or four times a week. Those qualities would later define Grif at his own trial.

Bird was eventually convicted but then the California Supreme Court, on appeal, ordered a new trial. This was nearly four years later and by then the district attorney had tired of the case so Bird walked out of jail a free man.

We’ll never know if Bird was telling the truth since he had reason to lie. But Grif himself, always looking for a laugh, once joked to a Times reporter writing about the donation that he was tired of paying those taxes. It also later was revealed that Grif initially planned to donate just 2,000, mostly hilly, acres, but that Mayor-elect Meredith Rader insisted on the 1,000 acres along the Los Angeles River so as to cement the city’s legal standing on water rights there.[4]

It’s also very possible that a vast park might never have happened had any one of Grif’s earlier rancho pursuits been successful. What if the ostrich farm and railway had continued to bring in crowds and homeowners? What if the 1880s Boom, instead of spreading south and east from downtown, had spread northwest to the rancho and allowed Grif to subdivide much of it? What if his 1889 advertisements to sell the entire rancho had found a buyer? Or if in 1890 when he tried to sell the city 100 Briswalter acres for a park – had it happened perhaps the massive Griffith Park would never have existed.[5] And at the start of 1896, had the treasure hunter found gold they’d both be rich and Grif no longer so burdened by the vast, mostly unusable rancho.

Those pursuits suggest Grif was getting tired of sinking money into the rancho with little return on investment. But it’s also true that Grif had a charitable streak, starting with the sale of Los Angeles River water rights to the city at a discount in 1884. Also, in his breakup letter to then fiancé Tina, he reminded her “how much good could be done” for others with their combined wealth. In 1891, he donated to the city stretches of two key roads just outside downtown that furthered development projects. Finally, when he decided on the park donation he didn’t resist Rader’s request for 1,000 acres along the river.

“The Prince of Los Feliz”

Grif certainly also appreciated the acclaim from his peers — the “Christmas gift” ceremony, which he must have organized himself since the donation was under wraps, was a testament to that. No quiet exchange with city officials, the proceedings on December 16 continued with speeches by the outgoing mayor, the incoming mayor, a councilman and two of Grif’s peers. And all that was followed by a dinner with more speeches at the prestigious California Club.

“The city of Los Angeles should feel prouder of this day than it ever has before,” Mayor-elect Snyder said at City Hall. Councilman Samuel Kingrey proclaimed that Griffith “has found a place… in the hearts of the children of this city, and in the hearts of the people that are to follow his generation and other generations — who shall never be forgotten.” Future Angelenos, he added, will “call this man blessed for the work which he has accomplished.”[6]

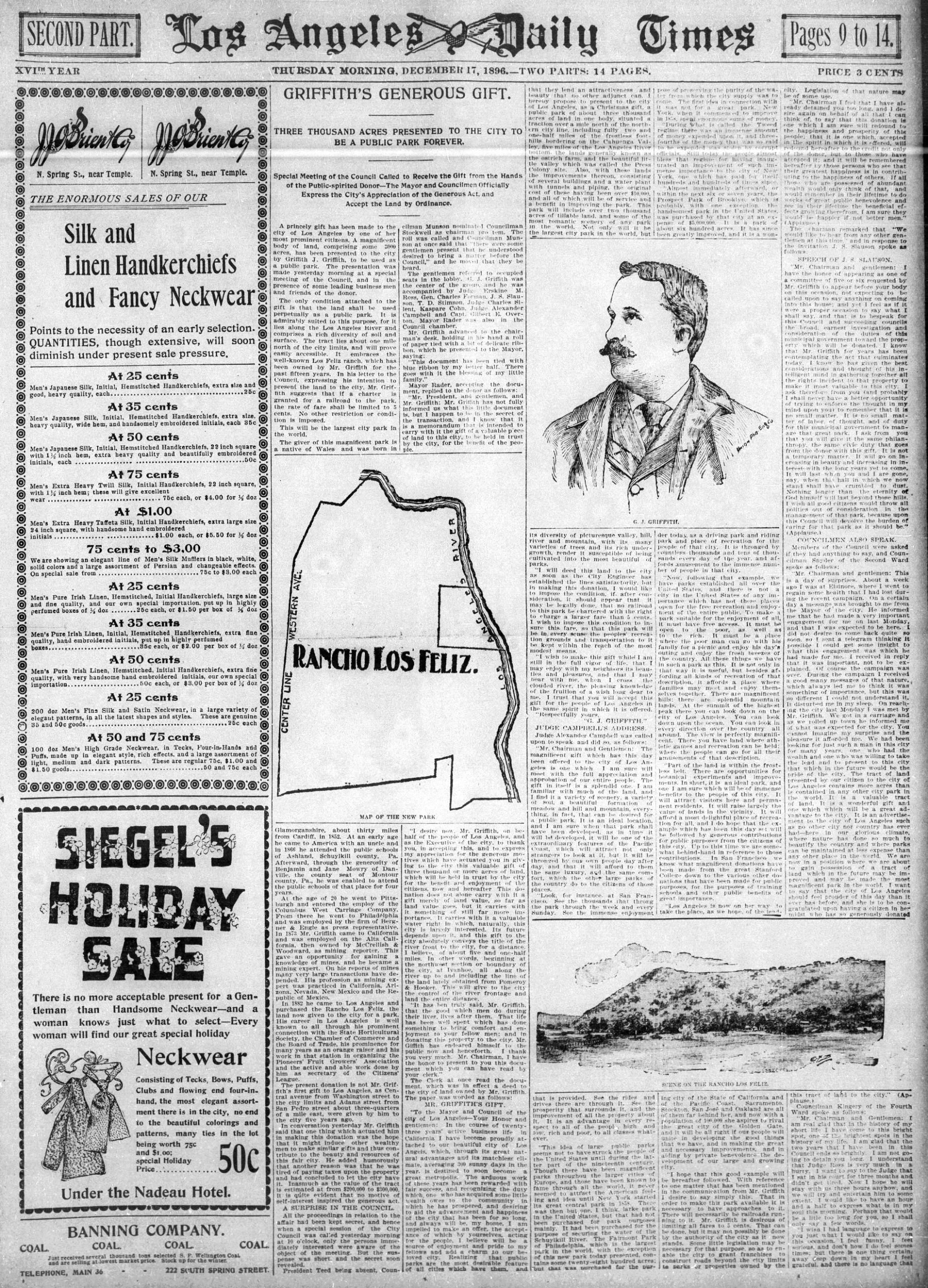

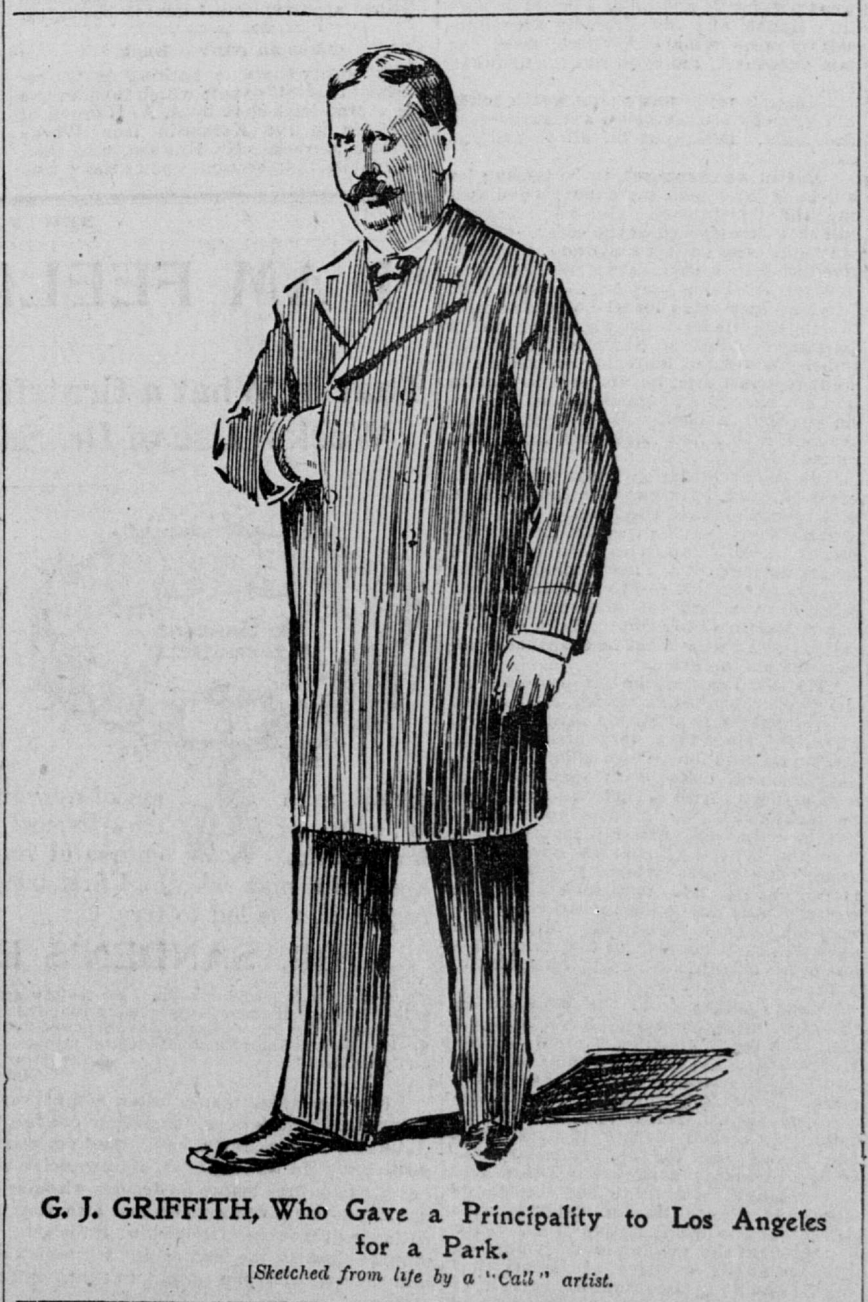

The Times and Herald published those accolades, each providing nearly two pages of coverage plus editorials praising the “princely gift”. The Times included a map of the donated land (see below), an illustration of the rancho, and a two-column sketch of the benefactor himself.

A week later, the Chamber of Commerce acknowledged Grif’s “munificent liberality” by awarding him its first-ever honorary lifetime membership. The Capital, a weekly social/gossip magazine popular among the local elite, waxed that “too many Scrooges” existed among wealthy Angelenos and that they needed to be “Griffithized”, i.e. create their own charitable legacies for the city.[7]

Within a few weeks, the organizers of the upcoming 1897 Fiesta made Grif one of its three new “knights” — men honored for improving the city. When the time came for the “knighthood”, Grif played his part well. Standing on stage before thousands of party goers, as well as the “queen” and her court, he was, the Herald reported, “garbed in deep royal purple velvet, square-cut coat, vest and knee breeches, heavily embroidered with silver, black hose and shoes with diamond buckles.”[8]

The Fiesta queen, in a proclamation read to the crowd, said her new knight had “shown unselfish love” and is “filled with kindness, with thought, with feelings, and with a love for mankind.”

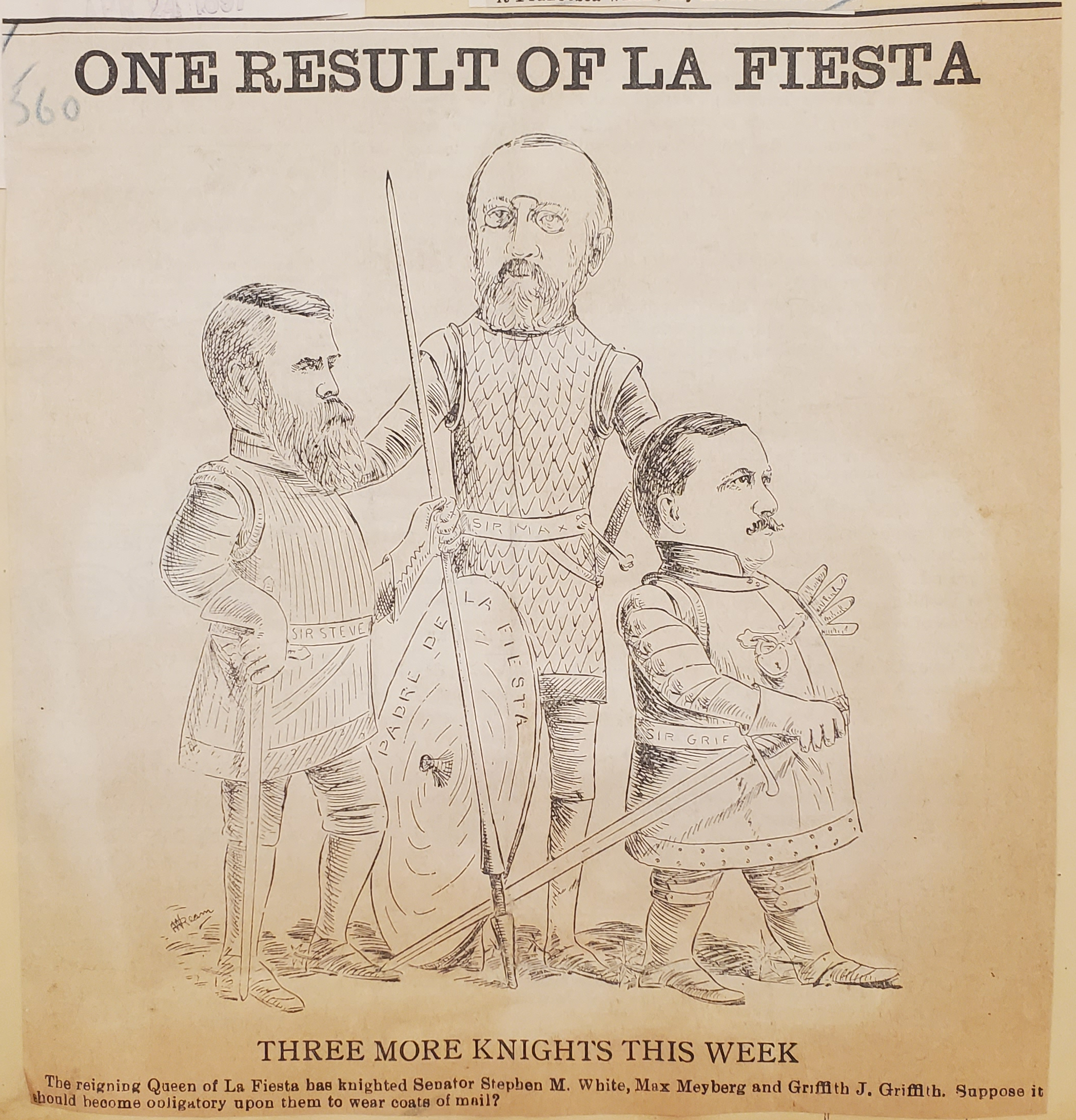

Some would say that Grif milked the donation for all it was worth — carrying himself around town like a West Coast Andrew Carnegie. The Herald dubbed him “The prince of Los Feliz”. The weekly Porcupine, which years earlier had described a pompous Grif, illustrated him (see below) alongside U.S. Sen. Stephen White and Fiesta organizer Max Meyberg — the two other Fiesta knights in 1897.

But even if Grif did try to gain respectability from the donation, he was clearly ahead of his time in imagining how the park could be a key amenity for the city, and especially its poorest residents. In his autobiography, he wrote that he was inspired by the great parks of Europe during a trip there in early 1882, just before settling in Los Angeles. He referred to that trip when he reminded city officials and others of just how large the donation was in comparison to the smaller parks he saw abroad.

Promoting the “Park”

The donation instantly made Grif the first American to give the public so much land close to an urban area. The next largest, the Fairmount Park in Philadelphia, was cobbled together with several tracts and all were acquired, not donated.

Not that Griffith Park was yet a real park. The land had zero amenities and it was over a mile from the city’s northern limits — a long haul at a time before cars were common and when no public transit went there. But it had potential, beginning with the 360-degree views from its foothills: downtown Los Angeles to the southeast, Santa Monica and the ocean to the west, tiny Hollywood to the north, and behind it the rural valleys that would soon house new cities and allow the southland to sprawl.

But as time went by, nothing ever happened to get the park funded for amenities. Grif periodically got praise, but that seemed to be followed by dismissive actions, or non-actions, from City Hall.

To start with, the press had described Grif as a shoe-in for one of the two seats on the Board of Park Commissioners that were opening up less than a month after the donation. But when the time came for the seven city councilmen to vote on January 4 (ironically Grif’s birthday!), only three backed Grif and so two other candidates were voted in along party lines, one Republican and one Democrat. A week later, the councilman representing the Republican Party said its commissioner would withdraw so that Grif could have a seat. But, as the Herald put it, Grif “could not see his way clear at the time to accept it.” He made no public statement, instead taking the high road by announcing in the same Herald article that he was inviting the City Council and Park Commission for a tour through the park later that month.[9]

What’s more, the city had made it clear that for now it had other financial priorities. Just meeting payroll was a challenge, and besides it had plans to first beautify Elysian Park, which was only 300 acres but closer to downtown.

One of Grif’s associates did offer to contribute $500 of his own money if others joined to create a $50,000 pot to start funding park improvements. The Times liked the proposal so much that it had a sign-up sheet at its business office — but alas nothing ever came of the idea.[10]

Round Two for a Real Park

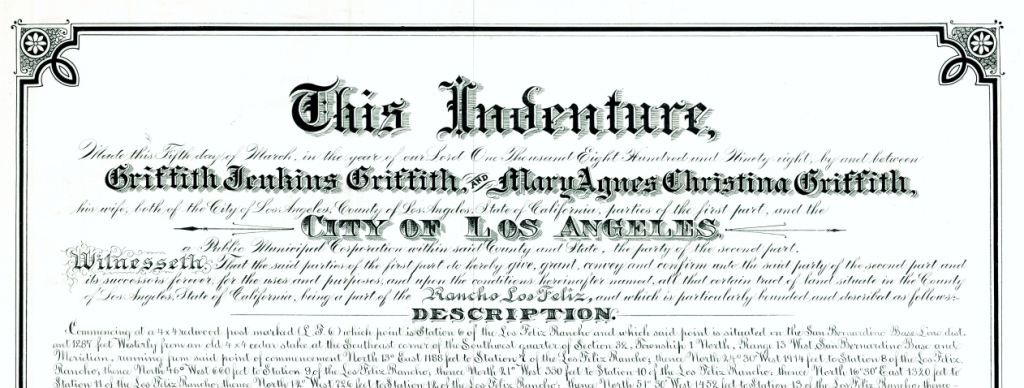

A year later, Grif got a chance to jump start the park back to life. Since determining the exact park boundaries was complicated given its size, the deed was not ready until 15 months after the donation. So, on March 5, 1898, another City Hall celebration was called and this one was even grander. The Herald noted the “immense bow of blue satin ribbon” that tied the deed as Grif walked in with an even bigger entourage this time — representatives from the Chamber of Commerce, the Board of Trade and the Merchants and Manufacturers Association, as well as the state’s foremost politician, lawyer and orator, Sen. Stephen White.

“An assembly more typical of the enterprise, push and solid wealth of the city would be hard to get together,” the Herald reported.[11] The praise was prolific. “In these days of grasping and money getting it is a cheering sight that one man can be found to make so magnificent a donation to the public weal,” proclaimed White in kicking off the ceremony. Echoed Mayor Snyder: “His action will live forever — will be spoken of by our children’s children — for the lives of good men, generous men, do live after them.” The leader of the fast-growing but cash-strapped city also had to get in a word to Grif’s wealthy peers. “Would to God that we had more men in our community like Colonel Griffith,” Snyder said. “I had hoped that his noble example would have borne fruit, but as yet it has not.”

Perhaps most interesting about the entire event was that while Tina did not attend — after all back then these things were handled by the men — she was represented and even acknowledged. City Council President Herman Silver, in his speech, said he’d noticed that the deed listed the donors as Grif AND Mary Agnes Christina Griffith and that she, too, had signed off on the transfer. The Times picked up on the curiosity that any male would even appreciate that, reporting: “Theoretically a man and his wife are one, not two, but in actual life it does not always work out that way, and the president, in expressing the thanks of the citizens of Los Angeles, did so to the joint donors, who had combined in making the gift.”[12]

Grif said a few words, elaborating on how the park came to be. “When I acquired the Los Feliz Rancho, and after visiting various countries and inspecting their parks, I determined, if ever I could afford it, to donate to the city this territory, believing it to be particularly well adapted for a park,” he told his audience. “I owed it to myself and my family to so shape my finances that I could do this and today this has been done and my wish has been fulfilled.”

What’s interesting about his choice of words is that, while Tina supported the donation (years later she stated so), Grif talks about “my wish”. And then there’s his need to “shape my finances” — ironic given that Tina’s inherited property was a big part of why Grif was able to be in good financial shape.

The deed itself was straightforward — lots of details about the boundary. But it also spelled out, and made legally binding, the park’s name. If the city “shall at any time change the official name of said park from GRIFFITH PARK to some other name or designation,” the deed stated with a sentence structure only a lawyer could love, “then the lands hereby conveyed shall immediately upon the happening of either said events revert to said parties of the first part or their heirs.” So, whereas the initial donation had no stated requirement for a park name, the final deed was definitive. That detail would later derail the efforts of those who, once Grif was convicted, wanted to rename the park.

The celebration concluded with several of Grif’s peers pledging $10 each for an unspecified monument marking the donation. Just like with the park improvement fund, however, nothing ever came of the plan.

The Herald and Times followed up with editorials calling for action to develop the park. The Times urged city spending so as to turn the park into “the Mecca of all visitors to Los Angeles.” The Herald’s lead editorial, titled “Paradise of the Pacific”, was a reflection on Griffith Park’s potential and included a long list of well-known parks worldwide that were much smaller.

Not So Happy Hunting

Grif saw he now had some momentum and the very next day, March 6, he went to the park to assess its condition. He was not happy with what he found: old oak trees had been cut for wood, and hunters were shooting birds and deer. “These hunters should not be permitted to invade the park and depopulate it of its beautiful songsters and other natural denizens,” he pleaded in a letter to the park commission. [13] How much he cared for the land was clear by how he described that wildlife. “Among the latter are several deer which are so tame that they have recently been seen drinking from the same trough as the dairy cows. Among the birds are thousands of golden oriole, meadow lark, California linet, mocking bird, blackbird, quail, sandhill crane and wild duck. These if unmolested in their accustomed haunts, will constitute a great charm for future visitors at the park, and I am sure every lover of nature will echo my wish that they should be permitted to consider the park their rightful home.”

To the city’s credit, especially given that the park was a mile outside city limits, a watchman was appointed two weeks later to patrol the park but, as for amenities, that was still a dry well. The city did entertain some other ideas. One was bananas, literally. The Cahuenga area west of the park was a frostless belt where tropical fruit, from bananas to pineapples, could be grown. Just two weeks after the deed went to the city, the local improvement association, basically landowners, offered to plant 10 acres of bananas inside Griffith Park in exchange for use of the land, the idea being to showcase the area to visiting investors, and thus inflate local land prices. Grif and the city were interested, but the idea soon dropped off the face of newsprint and was never heard from again.[14]

The city did take over a lease of land that had been Grif’s but was now part of the park, land that was being used to pasture cattle. The rancher had gotten away without pay rent in the first years of the park, but once the deed was transferred the city realized its legal standing and started demanding payment.[15] Grif certainly accepted the arrangement since it had started while he was owner, but it set a precedent for other farm uses in the park that Grif would later object to.

Another proposal that didn’t get very far was placing prisoner barracks on park grounds. The Chamber of Commerce came up with the idea in October 1898 as part of its proposed “City Charter” to reform what it saw as an inefficient local government. Voters rejected the charter and the barracks never appeared.[16]

The most grandiose idea, and the one with the longest shelf life, was that of using Griffith Park for a national arboretum. Grif loved the idea, telling the City Council there was “no better way to add to the glory and prestige of the city than to change this local into a national park.”[17]

It first came up on November 19, 1899, when the Times reported that Grif would be showing the park to a visiting federal official surveying possible sites for a national arboretum. The official was said to have become enchanted with the park and within a month the City Council unanimously approved the transfer to federal ownership.

The feds, however, came back and said no mechanism existed for the federal branch to receive a donation from a city branch of government. Instead, Congress would have to approve funds to buy the land for a national arboretum. Congressmen representing Los Angeles tried but failed to secure funding, thus ending another chapter in the park saga.

Diplomacy, Then Demands

After that, Griffith Park basically was out of public sight and mind until March 26, 1902, when it became clear that Grif wanted to light a fire under city officials. He organized a tally-ho for reporters to see the lack of improvements more than five years after his donation. That same day he fired off a letter to the mayor and City Council, which he also submitted to the Times, and got published the next day.

“You need only to have a few facts called to your attention,” he wrote diplomatically, “facts that doubtless have been overlooked in the pressure of other matters, to insure your righting a wrong”. To start with, he noted, “Nothing has been expended” to make it a park, and on top of that several hundred acres have been leased to farmers while old trees have been “ruthlessly destroyed and marketed for fuel.” In other words, those facts were adding injury (park destruction) to insult (his ignored legacy). Asking, but not demanding, he concluded: “Cannot our City Fathers, acting in behalf of the public, expend a modest annual sum to make its oak-dotted meadows, its beautiful canyons and its commanding heights accessible to the lovers of nature?”

A Times editorial that same day called the letter a “mortifying reminder of the city’s apparent indifference”. The Herald backed Grif as well editorially, and it had a reporter ask each park commissioner for their take on funding, but even that public spotlight didn’t change things. A few weeks later, Grif took the mayor and commissioners to see the park but that went nowhere as well.

Having had enough, and this time dropping the diplomacy, Grif fired off a letter to the press on July 1. The Herald published the full rant in a section called “The Public Pulse”. Grif noted that he had become hopeful when commissioners started talking about improvements, even building a paved road up to the park, but those “hopes were doomed to disappointment and the fair promises have ended in talk.” To which he added: “Talk is cheap”. He was also slighted by the lack of respect after all he had done for the city. The man who had sold the city water rights at a big discount, and made sure river frontage was part of his donation, was now being denied river water for the 350-acre parcel he retained after the donation. “When I applied to the city authorities for my usual water supply three years ago,” he complained, “it was denied me and has been denied me ever since, consequently I lost my tenant.”

Grif noted, too, that others were being allowed to farm parts of the park at a subsidized rate, and “many of the trees which I had carefully guarded for years” were still being cut down and sold for firewood. He then implied that the commissioners weren’t taking the park seriously, using “crude methods” and “shifting policy” to essentially put him and the park off. Perhaps the donation was “a grand mistake,” he added. “I did not dream … the park would be let out to wood choppers and turned into barley fields and cattle pastures,” he concluded. “It is doubtful if one person in a thousand in this city has ever visited its northern slopes or knows how to get there.”

Amid this rancor, Grif did enjoy a very special July 4 that year: Hollywood and Cahuenga Valley boosters feted him with a hike and American flag planting at the park’s highest point, and even informally named it Griffith Peak. “We look down upon this vast domain of mountains, canyons and winding valleys,” the chief speaker pronounced, “and are reminded that it is the gift of one unselfish citizen whose object was to benefit his fellow-man.”[18]

But the next few months saw even more accusations — Grif threatened to take back the park, while one adversarial city councilman crowed “it is time that pile of rocks went back to the source from whence it came.”[19] Finally, the city decided to seek a public vote for a $20,000 bond to improve the park. But that was shelved in October when the state Supreme Court decided it would rule on the legality of city bonds. Whatever optimism Grif had re-found was probably gone again by now.

Promise of Progress

It all looked hopeless for Grif — until 1903 ushered in a new political era in Los Angeles and nationally. The Gilded Age of capitalism at any cost was giving way to the Progressive Era and reforms meant to ease the pressure building up in cities across the country. From corrupt politics to the stench of industrial smokestacks, cities were becoming cesspools for discontent. America’s new president, Teddy Roosevelt, led the reform charge, with support across the country from folks like Grif.

At the city level, public sentiment was leaning towards taking back services such as water and transport from capitalists like Henry Huntington, who monopolized the local transit system. That was the context when, in January, Mayor Snyder appointed Grif and two allies to replace three park commissioners seen as representing the status quo. Snyder, who cleaned house in other parts of city government as well, got the look and feel of a Progressive administration, while Grif now had a public platform from which to fund the park he’d envisioned.[20]

Expenditures started to flow for new roads and trails inside Griffith Park, as did ideas, among them:

- The feds wanted to locate 100 elk in the park, an idea embraced by Grif as the start of a local zoo;

- The police chief suggested using the city’s prisoner chain-gang to build park roads;

- The Los Angeles & Glendale Railway proposed an extension of its electric line into the park from the Glendale area;

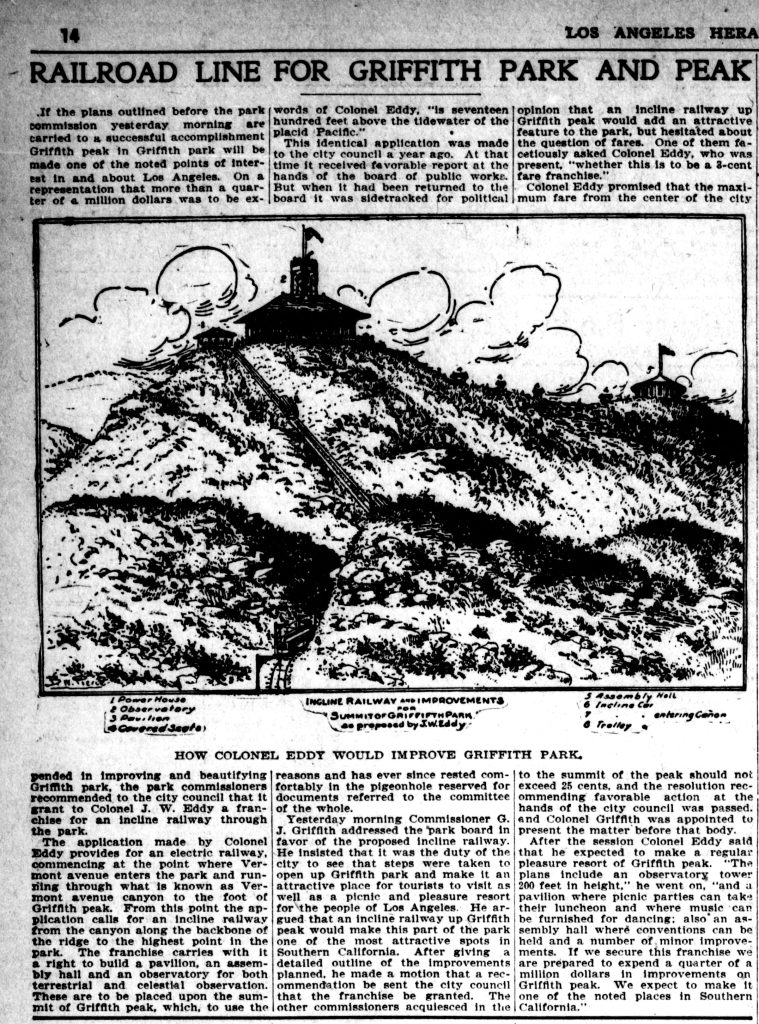

- Col. J.W. Eddy, the man behind Angel’s Flight, the popular incline railway on downtown’s Bunker Hill, wanted to create a funicular to Griffith Peak, complete with casino and dance hall at the top. Eddy promised to make it inexpensive, and thus had Grif’s blessing. The city accepted the proposal, which Grif backed with a $5,000 bond guarantee, on the afternoon of September 3, 1903 — ironically the same afternoon that Tina was shot.

It seemed the park’s time had come: even California’s Supreme Court eventually sided with the city on the issue of raising funds via bonds, and the Times quickly embraced a bond vote on the next ballot.

For reformers like Grif, it must have seemed as if they were creating a new world order. Their actions were becoming standards for others, later enshrined by activists like Dana W. Bartlett, a Protestant minister in Los Angeles who described benefactors like Grif as “Socialized Capitalists”.[21]

Both Roosevelt and Grif saw nature as playing a key role in releasing the class pressure building up in cities. Sure, compared to Roosevelt’s grandiose plans to protect vast wilderness areas for all to enjoy, Grif’s park seemed tiny. But think about the foresight Grif showed — in 1896, few actually believed the Chamber of Commerce’s boast that Los Angeles would soon overtake San Francisco and become the largest city on the West Coast. And if that was the mentality, who needs a huge park? But Grif and the chamber were spot on — within 24 years Los Angeles indeed surpassed San Francisco and never looked back.[22]

It wasn’t just the park that kept Grif busy, and socially prominent, in those years at the turn of the century. He was also helping develop and subdivide a farm town called Hollywood, gathering investors for the biggest “manufactory” on the West Coast, backing the “Good Roads Movement” spreading across the country, lobbying for the “Free Harbor” in San Pedro, and rising up within the local Republican Party, attending a national convention and even meeting Roosevelt.

At the same time, however, cracks were starting to line the facade of the Griffith marriage — warning signs dating as far back as 1900 that all was not well at home.

- Workman, The City that Grew, p225. ↵

- Times, July 6, 1999 and Herald, July 18, 1899. ↵

- Herald and Times, July 19, 1899. ↵

- Eberts, in Griffith Park, p9, cites a note by Van Griffith as the source of this claim. ↵

- The Express on July 23, 1890, reported Grif was offering to sell the 100 acres to the city for $75,000 when he felt they were worth $200,000. ↵

- Times, December 17, 1896. ↵

- The Capital, January 9, 1897. ↵

- Herald, April 21, 1897. ↵

- Herald, January 4, 5 and 12, 1897. ↵

- Times, December 27, 1896. ↵

- Herald, March 6, 1898. ↵

- Times, March 6, 1898. ↵

- Herald, March 8, 1898. ↵

- Herald, March 25 and 29, 1898. ↵

- Herald, December 23, 1898. ↵

- Herald, October 13, 1898. ↵

- Times, December 12, 1899. ↵

- Herald, July 5, 1902. ↵

- Express, September 8, 1902. ↵

- Mark Stevens in The Road to Reform notes Los Angeles later became the first big U.S. city to hold a nonpartisan primary election, p346, as well as the first where reformists united to defeat a political machine, p362. ↵

- Dana Bartlett, The Better Way, pp1-12. ↵

- Kevin Starr in Material Dreams, pp110-111, credits Grif with helping cement park planning in Los Angeles, adding that it took a few more years after Grif's death for other city elite to make such policy mainstream. It was only in 1927 that a citizen's panel on parks was created and filled by the likes of oil tycoons Edward Doheny and J. Paul Getty as well as Hollywood movie royalty. ↵