4

In order to help struggling students, it is important to be “wise to” their situations: students at the high school and college ages are going through crucial stages of self-exploration and self-definition, constantly creating new meanings and drawing inferences about themselves and where they fit in. At a cognitive level, this involves using Conway’s Self-Memory System, which refers to the interaction between the working self and the autobiographical knowledge base (Conway & Playdell-Pearce, 2000). The working self, or the person and their goals in the present moment, is constantly drawing upon knowledge from autobiographical memory, and activating schemas about the self. Memories validate and support aspects of our self-schemas (Conway & Playdell-Pearce, 2000), and as such, we use schematic memories to form identity. Thus, autobiographical memory is fundamental to the formation of a sense of self.

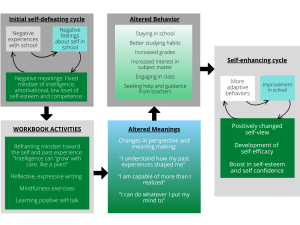

According to Markus & Ruvolo (1989), there is always some subset of the self-schema active and modulating cognition and behavior. When self-schemas are active, they guide our thinking about ourselves to generate “possible selves”—possibilities of who we could be, and who we could not be. This type of thinking and these internal narratives form a working self concept, which functions like a working hypothesis (Walton & Wilson, 2018). This is particularly true when a part of self concept is developing, which is the case in many areas of life for adolescents as they are trying new things, testing their abilities, and trying to find their place in society. Wise interventions aim to target these working hypotheses, and guide them to a more positive narrative. In the case of struggling students, the goal is to promote feelings of belongingness and self-efficacy in school. In a positive feedback loop, these feelings should lead to higher performance which fosters and more positive feelings about themselves in school and their academic abilities.

For example, a positive narrative like “I know I can do anything I set my mind to” can make a student feel competent and reaffirm that they belong in school, which motivates them to put higher quality effort toward academic endeavors. The higher quality effort will lead to academic improvement, which will give the student even more self-efficacious feelings and more feelings of belongingness. Thus, a positive cycle keeps the student thriving.

How people make sense of themselves and their personal situations is critical to their behavior (Walton & Wilson, 2018), so it is important to intervene when students develop negative self narratives about their academic skills and performance. Wise interventions can help to ensure that students have a fair chance at actualizing their academic potential and increasing their sense of self-efficacy. Without intervening, many students end up believing the negative self narrative so strongly that it restrains their abilities. How many times does a student have to think “I can’t do this; I’m not smart enough for this” for it to affect their academic abilities and motivation? The in-the-moment thoughts and goals of the working self inform what gets encoded to the autobiographical knowledge base, creating a sense of self and identity. The narratives we tell ourselves, then, directly affect our motivation and who we feel we are. The wise intervention aims to interrupt this self-fulfilling series of events by changing negative self narratives, so as to redirect the thinking pattern to a positive one. As described above, positive thoughts and feelings can then direct a person to a positive feedback loop which helps them believe they can succeed in school.