Private: Part II: Global Histories

Chapter 2: Global Sexualities

LGBTQ+ Anthropology, Past, Present, and Future

Joseph Russo

Introduction

Sexuality has long been an interest of sociocultural anthropological research. When anthropologists study sexuality, they examine how the values of a culture are expressed through sexuality practices by analyzing things like kinship systems, hierarchy, and social roles. Anthropologists are interested in not only categories of sexuality but also the purpose or function sexuality serves within a particular culture, as well as across cultures. Heterosexuality was the presumed norm in sexuality studies until the mid-twentieth century. Because of its widespread practice and its association with the reproduction of human life, heterosexuality has also been connected to the sustainment of human culture. Although widespread, heterosexuality varies across cultures, and anthropology has significantly contributed to understanding these differences.

This chapter discusses anthropological studies of non-Western and Indigenous sexualities that question the status of heteronormativity as a global model of social organization. Questioning the status of heteronormativity, however, does not mean that heterosexual kinship and the reproductive unit are not prominent features of nearly all cultures. Rather, this study of global sexualities shows the pertinence of questioning the imperative to be heterosexual. An understanding of sexual difference is enriched by putting sexuality practices in conversation with concepts of gender, race, and class and even with capital, industry, colonialism, and statecraft.[1] Instead of dismissing nonheteronormative sexuality as an outlier or anomaly, this chapter pursues culturally and historically specific data on different cultures across the globe to examine how LGBTQ+ anthropology posits the integral social function of these other sexualities.

Anthropology is the study of human societies and cultures. One of its subfields is sociocultural anthropology, which explores cultural variation, norms, and values. This subfield is the focus of this chapter, with an emphasis on sociocultural ethnographic studies of gender and sexuality. Ethnography is the systematic study of human cultures and is the primary qualitative research method used by anthropologists. Sociocultural anthropologists use ethnography’s immersive, experiential techniques to glean valuable knowledge about human behavior. For instance, they usually live in the communities they study, among the people who reside there, for a significant length of time, to understand life from the point of view of those being studied.

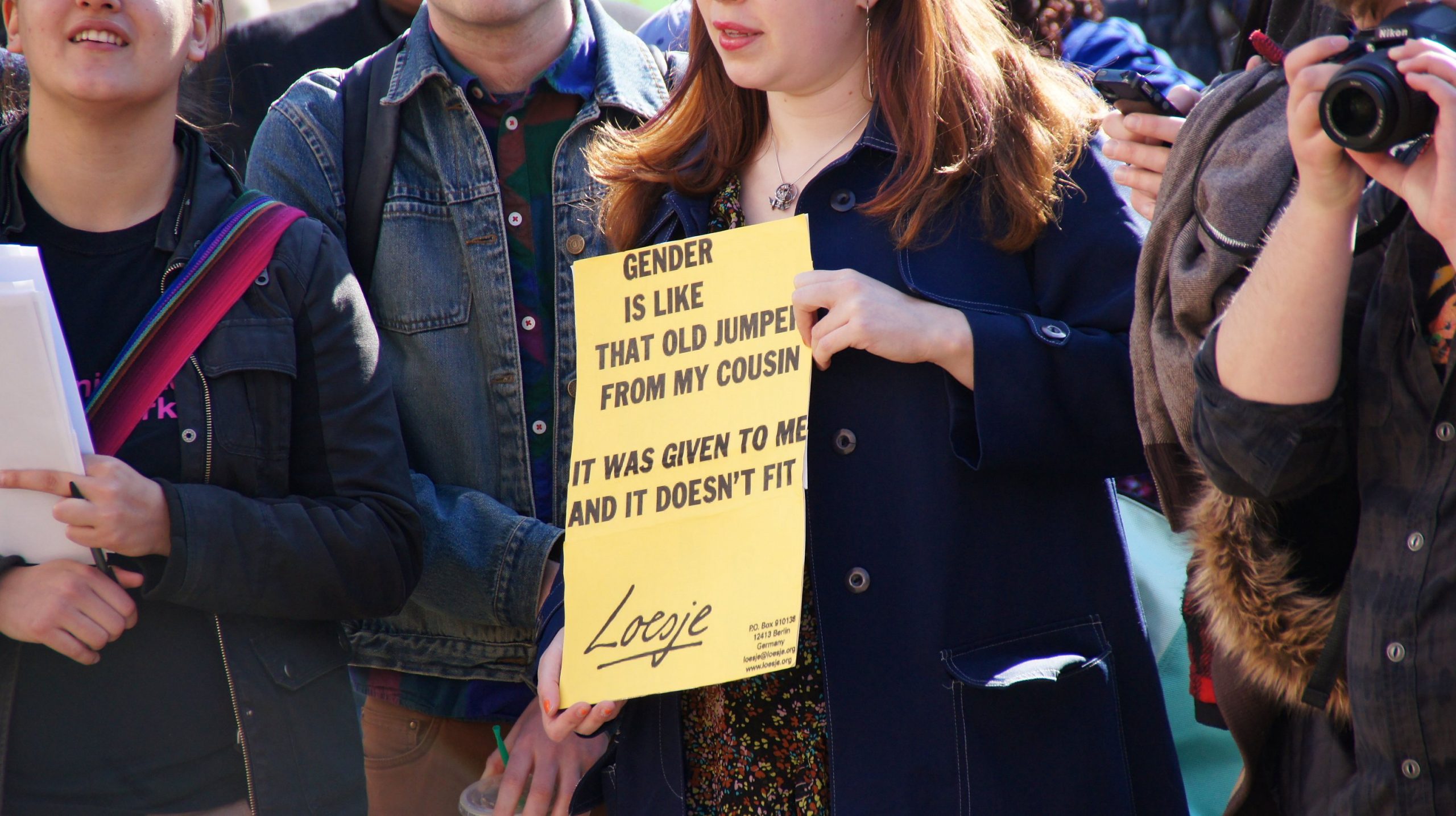

Previous distinctions between sexuality and gender and previous understandings of gender as a binary system do not stand up to scrutiny. The anthropology of sexualities explores the intertwining of gender and sexuality in a culture and the variations among cultures. Studies have found several ways that sex, sexuality, and gender relate to one another in different global cultures. They can form discrete yet related categories, have closely interwoven qualities, and even have qualities that directly inform one another and are occasionally interchangeable or confluent. Gender refers to the characteristics of femininity and masculinity that emerge as social norms and manifest in sociocultural practices and identities. Some theorists maintain that there are boundaries between gender identity and sexuality, but boundaries are not evident in all cultures and throughout all historical periods. Further, defining sexuality and gender as identity formations is not a universal practice. Some cultural conceptions of sexuality and gender see them as a collection of practices or functions.

Additionally, the commonly held belief in a gender binary is not a universal belief. Many cultures have a third gender, a fourth gender, and even a fifth gender. Other cultures understand certain individuals as neither male nor female, either because they embody both genders, moving between gender embodiments (gender fluidity), or they embody neither (gender neutrality). Most research on nonheteronormative gender and sexuality practices focuses on third-gender individuals who were assigned male at birth, but attention to other genders and sexualities is growing. Some other examples are third-gender individuals who were assigned female at birth and queer sexualities, such as female two spirit, gender-fluid queerness, and lesbianism. As discussed later, Native studies have traced this oversight to colonization and the effort of the colonizer to eradicate Native sexualities.[2] Under colonialism, the Native body was seen as sexually deviant. This belief helped justify the elimination and disappearance of Native people and was part of the systematic oppression inherent in colonialism.

Edward Carpenter was an outspoken socialist, philosopher, and activist early in the struggle for rights for homosexuals. His pioneering work Intermediate Types among Primitive Folk, published in 1914, explores the integral social function of nonheteronormative sexualities and gender practices.[3] This work is a combination of archival historical research and armchair ethnography that compiles field notes, travel writings, and anecdotes of settlers, explorers, and missionaries in their encounters with nonheteronormative sexuality and gender practices around the world. In the book, Carpenter developed the theory of intermediacy, which repositions nonheteronormative subjects (previously referred to as inverts or Uranians) to an ambiguously gendered middle ground. They occupy special positions, such as ritual practitioners or creators of arts and crafts. Carpenter includes in his account the samurai code of Japan and military practices in ancient Greece. Military histories from previous eras record same-sex pair bonds and sex acts between warriors. These were often societally enforced sexual and romantic bonds between men in mentorship and initiation, although the reasoning behind such activities and the way societies treated them is still a matter of debate. Carpenter calls these “intermediates,” an umbrella term for any person who falls outside the normative definitions of sexuality or gender practices.

During the mid-twentieth century, LGBTQ+ visibility and political organization in Europe and the United States increased, leading to a deeper engagement with Western LGBTQ+ culture by anthropologists. Esther Newton’s 1972 Mother Camp: Female Impersonators in America is often cited as the first U.S. ethnography on nonheteronormative sexuality and gender. Its subject is drag performance by drag queens (called female impersonators at the time) in the mid-twentieth-century United States.[4] Newton’s work encouraged other LGBTQ+ anthropologists to pursue ethnographic research of LGBTQ+ sexualities in the United States and around the world. Evelyn Blackwood’s pioneering edited volume The Many Faces of Homosexuality: Anthropological Approaches to Homosexual Behavior presented in 1986 a global ethnography of forms of homosexuality.[5] Feminist and gender theory, as well as the rise of queer theory, added complexity to some anthropological concepts. These theories continue to challenge the field today to address ethnographic research that supports LGBTQ+ people and feminist, anti-racist, and anti-colonialist and decolonizing perspectives. For example, one of anthropology’s main theories in studies on global sexualities is the adverse effects European colonialism has had—and continues to have—on the textures and conceptions of Indigenous sexualities and gender embodiments worldwide. These violent, homogenizing colonial encounters were rooted in racist, heteronormative religious orthodoxies that sought to erase Indigenous lifeways.[6]

Explore

Read about the history of the Association for Queer Anthropology and explore the association’s website (http://queeranthro.org/business/aqa-history/).

- Why did it take eight years from the introduction of the resolution on homosexuality to the first official meeting of the Anthropology Research Group on Homosexuality?

- On the “Resources” page, members share syllabi for classes on LGBTQ+ anthropology. Which class would you most like to take, and why?

Will Roscoe’s study of two-spirit Zuni people and the development of two-spirit activism in North America brought an Indigenous perspective to the idea of the erotic.[7] This reframing of the erotic accounted for sexuality on its own terms rather than in constant comparison to a norm from which sexual and gender practices deviate. Some queer Indigenous scholars developed the initialism GLBTQ2—that is, gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, queer, two spirit[8]—to describe the spectrum of sexualities and gender embodiments included in Indigenous conceptualizations of sex and gender. Embracing the terms queer and two spirit, these scholars argue for the decolonization of Indigenous sexualities, and they critique heteronormativity, finding it a product of colonialism. In so doing, these scholars insist on the autonomy of Indigenous people in controlling and contributing to knowledge production about themselves.

Anthropologists study nonheteronormative sexuality and sexual practices, both today’s globalization of Western LGBTQ+ sexualities and community and precolonial global sexuality and gender nonnormativity. The encounter of non-Western cultures with Western models of LGBTQ+ identity has had far-flung effects on identity politics and rights-based notions of identity and community. Governments and organizations even use pinkwashing, or LGBTQ+ people’s presence or themes, to simultaneously downplay or distract from other unethical or illegal, oppressive, and violent behavior.

Henry Abelove and John D’Emilio have suggested that so-called modern sexual identities such as heteronormativity and LGBTQ+ identity (specifically addressing gay male and lesbian identity and community formation) coincide with the rise of industry and capitalism of the late nineteenth to early twentieth centuries in the West.[9] D’Emilio connects the rise of lesbian and gay identities to the reduced centrality of the heteronormative family unit as a productive labor force necessary for self-sufficiency and survival. A thread in historical studies and cultural critique traces the now relatively common presence of LGBTQ+ communities globally through capitalism and industry, largely in urban centers. Anthropological contributions to this theory describe and document local, regional, and cultural variations, noting that queerness as such (individuals engaging in nonheteronormative sexual practices and gender embodiments) precedes these modern historical developments, often back to ancient periods.

Anthropological work emphasizes that Indigenous concepts and terminology more accurately describe the nuanced differences of Indigenous gender and sexuality than do Western LGBTQ+ neocolonial models. For instance, the Maori word for a same-sex partner is takatapui and is used as an identifier for LGBTQ+ identity in modern Maori culture. However, the term has a meaning beyond the mainstream Western definition of LGBTQ+ identity. It describes nonheterosexual identity generally as well as men who have sex with men but do not identify as LGBTQ+.[10] In Hawaiian culture, aikane is another culturally specific term that describes men and women who have same-sex relationships. Historically, this was a socially accepted role in Hawaiian culture. LGBTQ+ people may describe someone as aikane today, but the term retains nuances that the English-language lesbian or gay might not capture. Both terms were common in precolonial usage. Takatapui has become repopularized in today’s society and is used as a marker to create a distinction between Indigenous Maori modes of queerness and mainstream settler-colonialist LGBTQ+ models of identity.

The Americas

North America

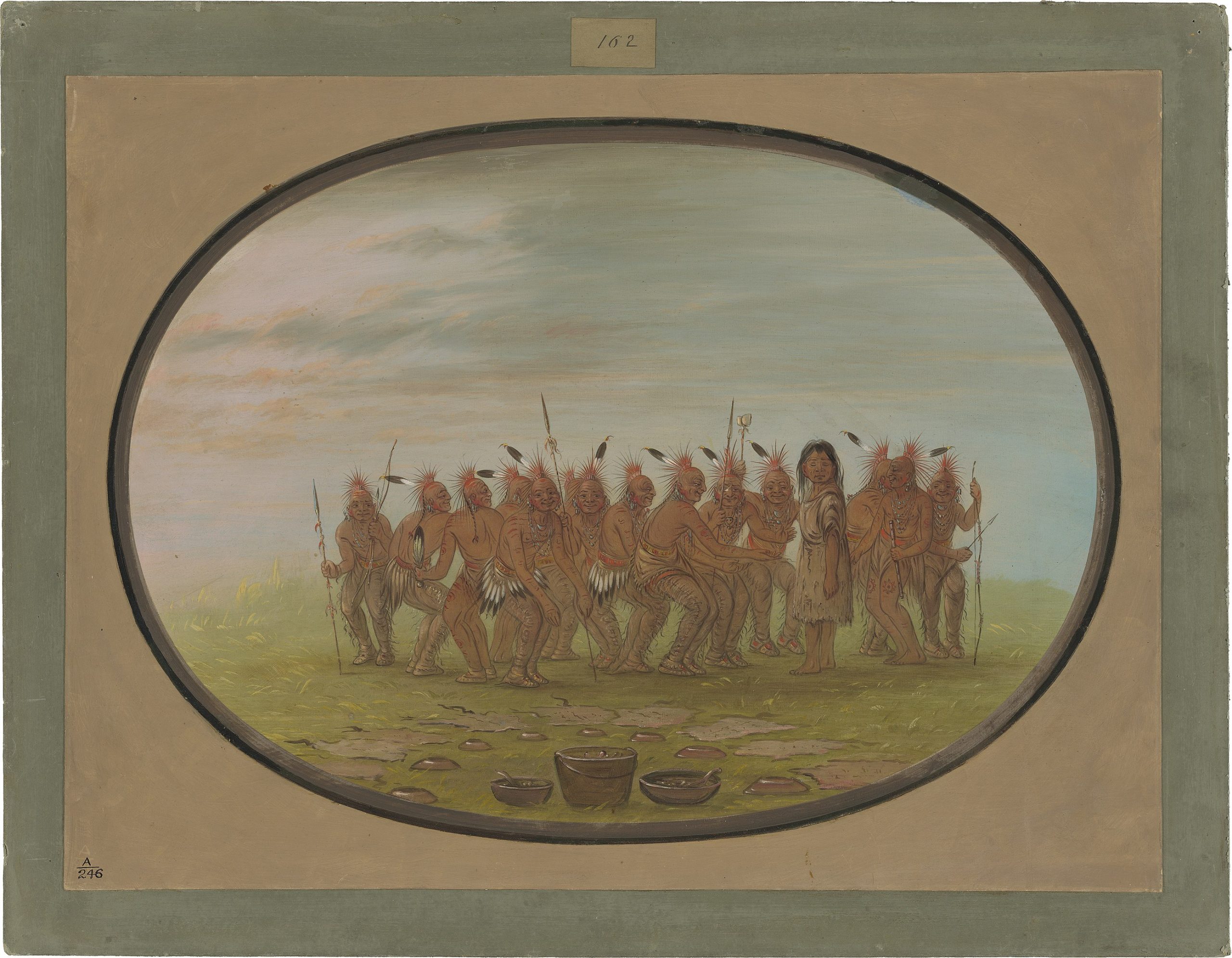

North American Indigenous conceptions of nonheteronormative sexuality and gender practices were documented by settlers, missionaries, and explorers. The individuals engaging in these practices traditionally held integral social roles that fulfilled particular social and ceremonial functions within their respective tribes. Seventeenth- and eighteenth-century white French settlers and missionaries labeled such a person a berdache (the term, denoting a passive homosexual partner or slave, is now usually rejected as a slur) (figure 2.2). Settler colonialists eventually discouraged these roles and violently eliminated those in them. Indigenous groups in the 1990s adopted the term two spirit to emphasize an individual’s experience of dual gender and spiritual embodiments. Two-spirit embodiment, while holding specific meaning and terminology intratribally, commonly signifies a religious or healer role. In Cherokee, the two-spirit term asegi translates to “strange” and is used by some as the modern connotation of queer.

The origin of the berdache role is unclear, and various reasons for the presence of two-spirit individuals have been offered. Some scholars interpret historical material as showing that communities probably assigned this social role, possibly foisting it on a feminine boy or extraneous son to be a passive sex partner, to bolster and reinforce a hierarchy.[11] However, this interpretation is largely rejected by the two-spirit community and is contradicted by the firsthand accounts of two-spirit individuals, such as Osh-Tisch. Also known as Finds Them and Kills Them, Osh-Tisch was a Crow badé (or baté; a male-bodied person who performs some of the social and ceremonial roles usually filled by women) who lived from 1854 to 1929 and famously fought in the Battle of the Rosebud. The story of Osh-Tisch suggests two major points about agency in Crow two-spirit social roles: (1) the role was a cultural institution and chosen by individuals who exhibited exemplary traits, such as excelling at women’s work, and (2) two-spirit individuals could also perform the roles of traditionally gendered males or females, as Osh-Tisch’s part in the Battle of the Rosebud suggests. Similarly, the idea that demographic necessity dictated who would be a two-spirit person is not sufficient to explain female two spirits. Many Crow women took on the traditionally male warrior role, making it difficult to classify two spirits as a response to a shortage of men. A well-known instance is Bíawacheeitchish (Woman Chief) of the Crow, 1806–1858.

Two-spirit presence has been noted in more than 130 Native American tribes. Among the Great Plains Indians alone are instances in the Arapahos, Arikaras, Assiniboines, Blackfoot, Cheyennes, Comanches, Plains Crees, Crows, Gros Ventres, Hidatsas, Kansas, Kiowas, Mandans, Plains Ojibwas, Omahas, Osages, Otoes, Pawnees, Poncas, Potawatomis, Quapaws, Winnebagos, and the Siouan tribes (Lakota or Dakota). Female two spirits, although documented among the Cheyennes, were more widespread among western North American tribes.[12] These practices were often, but not always, associated with nonheteronormative sexuality as well as nonbinary gender. Some two-spirit people engaged in same-sex or queer sexual or romantic and marriage relations.

The most common explanation for two-spirit embodiment suggests that the person prefers avocations traditionally associated with the opposite sex, experiences cosmological dreams and visions, or both. The conception of gender as a binary is challenged by two-spirit notions of being neither male nor female or being both male and female. Further, Inuit (culturally similar Indigenous peoples of the circumpolar North, Arctic Canada, Alaska, and Greenland) conceptions of nonheteronormative gender and sexuality were often connected to the Inuit shamanic role of an angakkuq. Although an angakkuq is not always or even usually nonheteronormative, inclusion of nonheteronormative people in its traditional social role shows an association with LGBTQ+ ways of being. Two-spirit people have also been noted in other Arctic cultural contexts, such as among the Aleutians, in Western Canada, and in Greenland.[13]

Latin America and Central America

The Zapotec in Mexico call themselves Ben ’Zaa, “cloud people.” They are Indigenous peoples concentrated in southern Mexico and especially in Oaxaca. Third-gender Zapotec roles such as muxe or muxhe in Oaxaca and biza’ah in Teotitlán del Valle receive more respect in regions where the Catholic faith has less influence than elsewhere and are believed to bring good luck to their communities. They are often thought of as caretakers of the community and of their families (figure 2.4). The Western notion of gender dysphoria does not describe the third-gender experience. Muxes are culturally accepted as not being in an either-or position. They are not placed on only one side of the male-female gender binary. Muxes have various sexualities that are not necessarily determined by their gender variance, which has local categories based on dress, including vestidas (wearing women’s clothing) and pintadas (wearing men’s clothing, sometimes wearing makeup). Also, if a muxe chooses a male partner (called a mayate), neither is necessarily thought of as a gay man or homosexual male.

South America

In South America, travestis are a well-studied LGBTQ+ group. The term is shared among Peruvian, Argentinian, and Brazilian cultures. Travestis are assigned-male-at-birth individuals who use female pronouns and self-identify on a gender spectrum. This spectrum runs the gamut from transgender to a type of third-gender role that is distinct from transgender identity. Travestis are often working-class sex workers. Their societal positions are precarious but also openly recognized. They are open to body modification and transitional surgeries and tend to favor black-market industrial silicone enhancements and intensive hormone therapies. Don Kulick’s study of Brazilian travestis, however, found that they had generally negative attitudes about gender-affirming surgery, preferring to retain their penises for their sex work. They also view transness itself as abnormal to some extent.[14] For these urban Brazilian travestis, gender was a men–not men binary, in which the not-men category encompassed women, homosexuals, and travestis. The travesti category describes a wide spectrum of self-identifying gender-nonnormative individuals,[15] a spectrum that often shifts with changes in politics, legislation, gender, medical science, and cultural conceptions of self.

Asia and Polynesia

South Asia

The Indian subcontinent’s transgender or third-gender category, hijra (referred to in different regions as aravani, aruvani, chhakka, and jagappa), is perhaps one of the more well-documented (by anthropology) nonheteronormative gender embodiments. Hijra is a social category that has been mobilized for political organizing, advocacy, and debate. Hijra people refer to themselves as kinnar or kinner—a reference to the Hindu celestial dance of the hybrid horse-human figure. From Indian antiquity to now, hijra people have been considered closer to third-gender categories than to modern Western binary notions of transgender.[16] In recent political developments, India and Bangladesh have legally recognized hijras as third-gender individuals. Interestingly, the word hijra derives from a Hindustani word that translates to “eunuch” and is used to designate actual eunuchs (people throughout history—most commonly men—whose genitals were mutilated or removed, often for social functions such as guarding women, singing, or religious purposes) and intersex people (those born with bodies that appear neither completely male nor female). Therefore, many third-gender people in India find the term offensive and have created more accurate and appropriate self-identifiers such as kinnar. In India and Pakistan, hijra people usually are employed in sex work. In this precarious and often violent occupation, they experience higher rates of violence, higher rates of HIV infection, and higher rates of homelessness, displacement, and depression.

Southeast Asia

Southeast Asian third-gender embodiments have also been influenced by globalization and capitalism. Third-gender individuals are popularly associated with industries that value their distinct cultural traits. In the Philippines, third-gender embodiments are referred to as bakla (in the Tagalog language), bayot (Cebuano and Bisaya), or agi (Hiligaynon and Ilonggo). Third-gender individuals are incorporated into the social and cultural structures of Filipino life and often work in the beauty and entertainment industries. Anthropologists such as Martin Manalansan have documented how modern bakla life is lived in the context of the diaspora, immigration, globalization, and community, noting that bakla presence challenges Western notions of gay identity and the assumed connection between LGBTQ+ people and progressive politics.[17]

In Indonesia, Evelyn Blackwood has explored tomboi identity among women who identify more closely with masculine cultural traits and enact masculinity in particular ways, thereby blurring the distinctions between male and female social roles.[18] In Thailand, third-gender and third-sex embodiments are described by the identifying term kathoey (or ladyboy).[19] These are distinctive identities, often understood as contrasting with trans identity in Thailand, but not exclusively. Scholars have noted that kathoey can describe a spectrum of gender and sexualities, ranging from trans woman to effeminate gay man, and opinions on what constitutes kathoey identity differ (figure 2.5). The historical connotation of kathoey was much wider; before the 1960s, it referred to anyone falling outside heteronormative sexuality or gender categories. The English translation of kathoey as “ladyboy” has been adopted across other Southeast Asian countries as well.

Polynesia and Pacific Islands

Polynesian language and culture have specific terms for LGBTQ+ identities and for third-gender or nonbinary assigned-male-at-birth individuals. These individuals are understood as embodying characteristics that lead them to self-select or to be socialized as women. In Samoa, the fa’afafine (meaning “in the manner of a woman” in Samoan) third-gender or nonbinary role,[20] similar to the muxe, has cultural associations with the family and hard work (figure 2.6). Fa’afafine is distinct from fa’afatama (male-to-female trans individuals), and the designation’s origin is disputed. The term may have been introduced in the nineteenth century with the advent of British colonialism and the introduction of Bibles translated into Samoan.[21] This suggests that before the introduction of Christianity, gender-variant individuals may have simply been referred to as fafine (women). Fa’afafine sexualities express along a spectrum, from male to female partners, although literature has suggested that fa’afafine do not form sexual relationships with one another. As in other cultures with nonbinary or third-gender individuals, fa’afafine celebrate their cultural heritage and gender variance in pageantry.

The word fa’afafine is cognate with other Polynesian language words in Tongan, Cook Islands Maori, Maori, Niuean, Tokelauan, Tuvaluan, Gilbertese, and Wallisian describing third-gender and nonbinary roles. In Hawaiian and Tahitian, the word is mahu. Third-gender or nonbinary assigned-female-at-birth individuals in Samoa can be referred to also as fa’atane. Dan Taulapapa McMullin, a fa’afafine scholar, argues that the shared history of the words fa’afafine and fa’atane and those individuals’ integral role in society demonstrate that Samoan culture lacks heteropatriarchal structures. He further observes that daughterless Samoan families choosing a son to become a fa’afafine is an anthropological myth.[22] McMullin notes that Western anthropological work on Samoan culture that is seen as authoritative conflates gender and sexual categories in order to make false statements about the status of fa’afafine.[23] Further, the suppression of gender variance in the Samoa Islands in the nineteenth century was a direct and violent result of British colonialism and missionary work. Third-gender identities of Samoan migrants to the United States and Europe were also repressed.

East Asia

Japanese cultural norms around nonheteronormative sexuality and gender practices have shifted over time. Historians have focused on the homosexualities of men. These are traced through ancient homoerotic military and warrior practices of samurai and gender embodiments used in ancient times for sacred and erotic purposes. For example, adolescent boys dressed as traditional geishas in the third-gender wakashu role (figure 2.7). Male homosexuality in ancient and premodern Japan is generally separated into the categories of nanshoku (translating to “male colors” and referring to practices of sex between men) and of shudo and wakashudo (translating to “the ways of teenage and adolescent boys”). The decline of these terms’ use and the discouragement of these practices began with the rise of sexology in Japan in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (Meiji period), when Western notions of sex and sexuality started to replace traditional Japanese norms. Homosexual practices were relegated to areas of Japanese society in which certain transgressions were tolerated, such as among Kabuki performers, some of whom dressed as women. Kabuki and Noh theater barred women from performing, and males played female roles.

Today, homosexuality practices in Japan are similar to the Western model, with culturally specific variations. Homosexuality is not illegal, but as of 2022, same-sex marriage was still not legal at the national level. Same-sex partnerships are recognized in some cities, and antidiscrimination laws vary according to region, much as in the United States and Europe. The LGBTQ+ community is especially visible in urban centers like Tokyo and Osaka, and modern terms for gay and lesbian identities exist. Also, nonnormative gender categories exist, such as the genderless danshi. These are generally young men who adopt third-gender and androgynous elements (e.g., makeup) but who often define themselves using cisgender and heterosexual markers. Danshi are often public performers—for example, musicians—whose fan base is mostly adolescent girls. Some gay erotica and media in Japan, such as the yaoi genre, typically depict adolescent boys in romantic or erotic relationships. Yaoi is generally authored by women and read by adolescent females. Conversely, bara, another form of gay erotica, is made primarily by gay men and has a majority-gay male audience. Among the audience are men who love men (MLM) and men who have sex with men (MSM); both types may or may not self-identify as gay.

Africa

African formations of sexuality and gender include culturally specific norms of Indigenous groups in urban, rural, and religious contexts. Rudolf Gaudio’s work on ‘yan daudu (or “effeminate men” in the Hausa language) in the northern Nigeria city of Kano finds differences between sexual identity and sexual practices. ‘Yan daudu are thought of, by themselves and by the public at large, as effeminate male sex workers who are not necessarily homosexual, even though they regularly have sex with men. They also occupy a socially ambiguous space with regard to their Islamic faith.[24] Regine Oboler studied female husbands among the Nandi of Kenya. She describes a cultural position occupied by older, childless (or more specifically, without a son) women who marry other women. They take on wives, receive bridewealth, and perform male duties, while not necessarily making their position part of their sexualities or gender embodiments. Oboler argues that maleness and the woman-woman marriage bond is understood as a matter of necessity and function in Nandi patrilineal societies.[25] Some authors argue that Oboler did not sufficiently explore the possibilities of a sexual relationship between the women.[26] Ifi Amadiume similarly explores female husbands in Igbo culture, as does Kenneth Chukwuemeka Nwoko.[27] Among the Tanala, a Malagasy ethnic group in Madagascar, third-gender-embodied individuals are referred to as sarombavy. They have been described as occupying a cultural position like that of Native American two spirits. The Swahili on the East African coast also have third- or alternative-gender identities (figure 2.8).

In the late twentieth century, leaders of new African states typically derided homosexuality as un-African, and they supported the persecution of lesbians and gay men. Nonetheless, after decades of struggle against apartheid in South Africa, the new South African constitution in 1996 enshrined protections against discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. The increase in studies on postcolonial LGBTQ+ rights and gender nonconformity and sexual minorities in Africa constitutes a relatively recent pan-African political movement. In postcolonial African cities, sexual violence against lesbians in South Africa and gender- or sexuality-based oppression and violence have occurred.[28] Scholars have focused on a variety of topics, including sexual violence against lesbians in South Africa and knowing women, a term for working-class women in southern Ghana who share friendship and intimacy.[29] The twenty-first century has witnessed a surge of activism by gender and sexual minorities across Africa. This activism promotes both Indigenous terms and histories of sexuality and gender. It also draws on international LGBTQ+ culture and activism in creating identities that resist and critique colonial and neocolonial heteronormativity.

Europe

Binary formations of sexuality and gender are widely characterized as Western, European, Euro-American, or American. European cultures, however, also have multiple instances of third-gender or nonbinary gender formations. For example, Italy’s traditional Neapolitan culture has the femminiello (the plural form is femminielli), an assigned-male-at-birth homosexual with gender-variant expression (figure 2.9). Members of this group play prominent roles in cultural festivities. These individuals have specific roles in religious parades, are often asked to hold newborn infants, and participate in games such as bingo and raffles (tombolas). Moreover, recent studies suggest that today’s Neapolitan culture is more accepting of femminielli than mainstream LGBTQ+ notions of sexuality and gender.[30] This assignation as femminiello is associated with the long-standing references to gender ambiguity (androgyny) and intersex individuals in Italian custom, going back to ancient myths about Hermaphroditus (the intersex son of Aphrodite and Hermes) and Tiresias. The cult of Hermaphroditus traces back to ancient Cypriot rites in which men and women exchanged clothing before the statue of a bearded Aphrodite.

Rictor Norton chronicles eighteenth- and nineteenth-century England’s molly houses, meeting places for gay men, or mollies—although it is unclear whether this term was a pejorative one or used as a self-designator.[31] Socializing, romancing, and same-sex sexual encounters took place there, as well as cross-dressing activities such as faux-wedding rituals between men and mock births (figure 2.10). These venues were illegal, and homosexuality of any kind was a capital offense in England until the late nineteenth century. Police regularly raided molly houses, and the homosexuals who frequented them were recognizable social types. This complicates Michel Foucault’s suggestion that the public categorizing and punishment of homosexuals and homosexuality did not begin until later.[32]

Conclusion

Throughout history and all around the world, many peoples engaged in same-sex relations. In many societies these practices were accepted and even celebrated. Christianity and colonialism were two key forces that brought homophobia to many societies and influenced local social constructions of gender and sexuality. The study of global sexualities is an ever-evolving discipline. This chapter describes the range of gender and sexual practices that have existed in different places and times and that continue to evolve. In the twenty-first century, globalization continues to spread Western notions of LGBTQ+ liberation, and in turn, local and regional cultural practices affect contemporary Western expressions and struggles over gender and sexuality.

Profile: Lukas Avendaño: Reflections from Muxeidad

Rita Palacios

Lukas Avendaño (1977–) is a muxe artist and anthropologist from the Tehuantepec isthmus in Oaxaca, Mexico. In his work, he explores notions of sexual, gender, and ethnic identity through muxeidad. Avendaño describes muxeidad as “un hecho social total,” a total social fact, performed by people born as men who fulfill roles that are not typically considered masculine. Though it would be easy to make an equivalency between gay and muxe or between transgender and muxe, it can best be described as a third gender specific to Be’ena’ Za’a (Zapotec) culture. Muxes are a community of Indigenous people who are assigned male at birth and take on traditional women’s roles, presenting not as women but as muxes. Avendaño’s work is a reflection on muxeidad, sexuality, eroticism, and the tensions that exist around it. Though muxeidad is understood and generally accepted as part of Be’ena’ Za’a society, it exists within a structure that privileges fixed roles for men and women, respectively. It is important to note that his work provides a reflection on muxeidad from within rather than without—that is, he critically explores what it means to be muxe as muxe himself, providing an alternative to academic analyses that can exoticize.

In Réquiem para un alcaraván, Avendaño reflects on traditional women’s roles, particularly in rites and ceremonies of the Tehuantepec region (a wedding, mourning, a funeral), many of which are denied to muxes. For the wedding ceremony, the artist prepares the stage by decorating for the occasion and then, blindfolded, selects a member of the audience who presents as male to marry him. Such a union would not be well regarded in traditional Be’ena’ Za’a society, even though same-sex marriage was recently legalized in Oaxaca, an initiative spearheaded by a muxe scholar and activist, Amaranta Gómez Regalado, in August 2019.

- Figure 11.8. The Miseducation of Cameron Post by Emily M. Danforth. (Deborah Amory.)

- Figure 1.7. José Esteban Muñoz. (From Queer: A Graphic History by Meg-John Barker and Jules Scheele, provided courtesy of Icon Books. Copyright Icon Books, reprinted with permission.)

On May 10, 2018, in Tehuantepec, Avendaño’s younger brother, Bruno Avendaño, disappeared during a brief vacation from his duties in the navy. He hasn’t been found since, and the artist has used his platform as an international artist to bring attention to the issue of the disappeared in Mexico. Other artists and activists join him as he travels around the world to show his work and create spaces where he can ask for answers at Mexican consulates and embassies for his brother as well as the more than sixty thousand individuals who have disappeared in Mexico in the last decade and a half.

Profile: Queering Pan-Africanism

Adriaan van Klinken

The recent politicization of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) identities and rights in many parts of Africa has given rise to a renewed emergence of pan-Africanist thought in two directions.[33] First, there is the well-known narrative of antiqueer pan-Africanism, invoked by many African statesmen, clergy, and opinion leaders. It uses sexuality as a key site to defend and preserve African values and identities vis-à-vis perceived foreign imperialism. LGBT sexualities are framed here as “un-African,” and violence against sexual minorities is legitimized in the name of “African pride.” The Ugandan human rights lawyer Adrian Jjuuko summarizes this as the “rise of a conservative streak of pan-Africanism.”[34] Second, and of greater interest here, LGBT activists and allies across the continent resist this popular narrative through a discursive counterstrategy in which they deploy progressive Black and pan-Africanist figures, ideas, and symbols.

One key example of this emerging discourse is the African LGBTI Manifesto, drafted at a meeting in Nairobi in April 2010 by activists from across the continent.[35] It opens with a strong, explicitly pan-Africanist vision: “As Africans, we all have infinite potential. We stand for an African revolution which encompasses the demand for a re-imagination of our lives outside neo-colonial categories of identity and power.” The manifesto then explicitly states its specific concern with sexuality but links it to the project of “total liberation” of the African continent and its peoples: “We are specifically committed to the transformation of the politics of sexuality in our contexts. As long as African LGBTI people are oppressed, the whole of Africa is oppressed.”

A similar emphasis on mainstreaming sexuality in a broader project of decolonization is found in the emerging body of literature in African queer studies. For instance, Sokari Ekine and Hakima Abbas state that “at the root of queer resistance in Africa, is a carrying forward of the struggle for African liberation and self-determination.”[36] African queer politics is a project concerned not just with LGBT identities and rights but with the struggle against patriarchy, heteronormativity, homophobia, and neoliberal capitalism. It aims at a comprehensive liberation of African peoples and societies from the multiple structures of domination and oppression.

As much as the queer African project is about the future of the continent, there is a critical sense of retrieving something that has been lost in the course of history and that can be recovered for contemporary political purposes. In the talk titled “Conversations with Baba,” the late Kenyan literary writer Binyavanga Wainaina uses an inclusive “we” to reclaim Africa as a continent that has always been characterized by diversity, and he thus sets an example to the rest of the world: “We, the oldest and the most diverse continent there has been. We, where humanity came from. We, the moral reservoir of human diversity, human aid, human dignity.”[37]

In Wainaina’s commentary, this rich and strong tradition of diversity characterizing African societies was only interrupted by “those people who came from that time of colonization to split us apart, until our splitting apart came from our own hearts.” Thus, he suggests that the interruption came from outside—from the forces of colonialism and missionary Christianity; he further suggests that moral conservatism and rigidity have been adopted and internalized by certain sections of society in postcolonial Africa, in particular conservative religious actors such as Pentecostal Christian pastors.

Vis-à-vis such forces, Wainaina calls for a reclaiming of indigenous African moral traditions that recognize human diversity. In part two of his six-part video “We Must Free Our Imaginations,” Wainaina describes sociopolitical and religious homophobia in Africa as “the bankruptcy of a certain kind of imagination.” He urges fellow Africans to engage in creative, liberating, and imaginary thinking, reclaiming the past in order to reimagine the future—a future free from oppressive modes of thought.

In a more popularized form, the same narrative is found in the “Same Love” music video.[38] Released in 2016 by the Kenyan band Art Attack under the leadership of the openly gay musician and activist George Barasa, the video was presented as “a Kenyan song about same-sex rights, LGBT struggles, and civil liberties for all sexual orientations.” The lyrics and imagery present a progressive pan-Africanist vision, which unfolds in two steps. First, the video draws critical attention to the recent politics against homosexuality across the continent, showing newspapers with strong and sensationalist antigay messages and images of Kenyan antigay political protests. This part of the song concludes by stating,

Homophobia is the new African culture / Everyone’s the police, Everyone’s a court judge, mob law, street justice / Kill ’em when you see ’em / Blame it on the west, never blame it on love, it’s un-African to try and show a brother some love.

In the next part, the lyrics specifically refer to Uganda and Nigeria, the two countries that in 2015 became internationally known for passing new anti-homosexuality legislation. Then the song calls upon Africa as a whole, saying,

Uganda stand strong, Nigeria, Africa, it’s time for new laws, not time for new wars / We come from the same God, cut from the same cord, share the same pain and share the same skin.

A positive pan-Africanist vision is presented here, emphasizing the unity and common history of African peoples. The basis for this vision is a religious one: the idea of African peoples as created by God. This echoes an important tradition of religiously inspired pan-Africanist thought, centering on the belief “that Africa’s destiny is God given.”[39] In the words of Marcus Garvey, “God Almighty created us all to be free.”[40] Originally, this religious notion allowed for resisting racial discrimination and overcoming the inferiority of people of African descent vis-à-vis white superiority. “Same Love” appropriates it to resist sexual discrimination and to overcome divisions that exist today about who counts as truly African.

In its opening statement—“This song goes out to the new slaves, the new blacks”—“Same Love” situates the experience of same-sex-loving people in Africa in a longer history of racial and ethnic oppression. The lyrics suggest continuity between the civil rights movement in the United States and the contemporary LGBT rights movement in Africa. This is acknowledged later in the video when images of some prominent African queer individuals appear on the screen, while the vocals in the song state that “Luther’s spirit lives on.” The suggestion is that the spirit of Martin Luther King Jr. lives on in those Africans campaigning for the human rights of sexual minorities today. This allows the producers of the video to claim a moral high ground, implicitly appropriating King’s prophetic dream of racial liberation in the United States and applying it to the struggle for queer freedom in Africa.

Wainaina has also invoked the name of King, and of the African American literary writer James Baldwin, as part of his queer pan-Africanist imagination. He referred to Baldwin as a source of inspiration, recognizing him as “black, African, ours,” as a “gay icon of freedom,” and canonizing him as a writer of “new scriptures” (figure 2.14). While commenting on the anti-homosexuality bill in Uganda, he further stated that the pastor of the former U.S. president George W. Bush “has had more influence on the imagination of Africans than Martin Luther King and James Baldwin.” Elaborating on this, Wainaina invoked the tradition of progressive Black religious thought, explicitly referring to “the Jesus of James Baldwin and Martin Luther King,” which, he critically observes, is “a dead man in Africa” (figure 2.15).[41] Describing Jesus as a liberating figure, who is in solidarity with the marginalized, Wainaina criticized the church in Africa for maintaining structures of oppression and exclusion.

The invocation of progressive traditions of Black religious thought is particularly significant in light of popular discourses that denounce homosexuality as both un-African and un-Christian. The question of whether religion, in particular Christianity, can make a constructive contribution to queer pan-Africanist discourse is a debatable one. Many African queer scholars and activists tend to see Christianity as a colonial and conservative religion from which Africa and Africans need to be liberated. This is understandable, but one could ask whether it not also reflects the influence of Western queer scholarship and politics with its secular inclination and anti-religious tendencies. Both Wainaina and the “Same Love” video agree with the postcolonial critique of Christianity. Yet they also suggest that progressive traditions of Christian thought can inspire the Black African queer imagination. Hence, they invite us to engage creatively and constructively with the resources within religious traditions toward Black pan-African queer liberation.

Media Attributions

- Figure 2.4. © Mario Patinho is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 2.5. © Fairtex from Thailand is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 2.8. © Collen Mfazwe of Inkanyiso is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 2.14.

- Figure 2.15.

- M. Rifkin, When Did Indians Become Straight? Kinship, the History of Sexuality, and Native Sovereignty (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011). ↵

- C. Finley, “Decolonizing the Queer Native Body (and Recovering the Native Bull-Dyke): Bringing ‘Sexy Back’ and Out of Native Studies’ Closet,” in Queer Indigenous Studies: Critical Interventions in Theory, Politics, and Literature, ed. Q.-L. Driskill, C. Finley, B. J. Gilley, and S. L. Morgensen (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2011), 31–42. ↵

- E. Carpenter. Intermediate Types among Primitive Folk (New York: Mitchell Kennerley, 1914). ↵

- E. Newton, Mother Camp: Female Impersonators in America (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1972). ↵

- E. Blackwood, The Many Faces of Homosexuality: Anthropological Approaches to Homosexual Behavior (London: Routledge, 1986). ↵

- S. L. Morgensen, “Theorising Gender, Sexuality, and Settler Colonialism: An Introduction,” Settler Colonial Studies 2, no. 2 (2012): 2–22. ↵

- For two-spirit Zuni peoples, see W. Roscoe, The Zuni Man-Woman (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1991); for development of two-spirit activism in North America, see S-E. Jacobs, W. Thomas, and S. Lang, eds., Two-Spirit People: Native American Gender Identity, Sexuality, and Spirituality (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1997). ↵

- Q-L. Driskill, C. Finley, B. J. Gilley, and S. L. Morgensen, eds., Queer Indigenous Studies: Critical Interventions in Theory, Politics, and Literature (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2011). ↵

- H. Abelove, “Some Speculations on the History of Sexual Intercourse during the Long Eighteenth Century in England,” Genders, no. 6 (1989): 125–130, https://www.utexaspressjournals.org/doi/abs/10.5555/gen.1989.6.125; John D’Emilio, “Capitalism and Gay Identity,” in The Lesbian and Gay Studies Reader, ed. H. Abelove, M. A. Barale, and D. M. Halperin (New York: Routledge, 1993), 467–476. ↵

- C. Aspin, “Exploring Takatapui Identity Within the Maori Community: Implications for Health and Well-Being,” in Driskill et al., Queer Indigenous Studies. ↵

- See, e.g., R. Trexler, “Making the American Berdache: Choice or Constraint?,” Journal of Social History 35, no. 3 (2011): 613–636. ↵

- Roscoe, Zuni Man-Woman. ↵

- J. Briggs, “Eskimo Women: Makers of Men,” in Many Sisters: Women in Cross-Cultural Perspective, ed. C. Matthiasson (New York: Free Press, 1974), 271; J. Briggs, “Expecting the Unexpected: Canadian Inuit Training for an Experimental Lifestyle,” Ethos 19 (1991): 266; J. Robert-Lamblin, “Ammassalik, East Greenland: End or Persistance of an Isolate? Anthropological and Demographic Study on Change,” Meddelelser om Gronland, Man and Society (Museum Tusculanum Press, 1986), 42. Saladin d’Anglure found the same percentages in his area, see B. Saladin d’Anglure, “Du foetus au chamane: la construction d’un ‘troisieme sexe’ inuit,” Etudes Inuit 10 (1986): 68. ↵

- D. Kulick, Travesti: Sex, Gender, and Culture among Brazilian Transgendered Prostitutes (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998). ↵

- J. Fernández, Cuerpos Desobedientes: Travestismo e Identitad de Genero [Disobedient bodies: cross-dressing and gender identity] (Barcelona, Spain: Edhasa, 2004). ↵

- R. Talwar, The Third Sex and Human Rights (New Delhi, India: Gyan, 1999); Dayanita Singh, Myself Mona Ahmed (Zürich, Switzerland: Scalo Verlag, 2001). ↵

- M. Manalansan, Global Divas: Filipino Gay Men in the Diaspora (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003). ↵

- E. Blackwood, “Tombois in West Sumatra: Constructing Masculinity and Erotic Desire,” Cultural Anthropology 13, no. 4 (1998): 491–521. ↵

- R. Totman, The Third Sex: Kathoey—Thailand’s Ladyboys (London: Souvenir Press, 2004). ↵

- N. Bartlett and P. Vasey, “A Retrospective Study of Childhood Gender-Atypical Behavior in Samoan Fa’afafine,” Archives of Sexual Behavior 35, no. 6 (2006): 659–666. ↵

- D. T. McMullin, “Fa’afafine Notes: On Tagaloa, Jesus, and Nafanua,” Amerasia Journal 37, no. 3 (2011): 114–131. ↵

- McMullin, “Fa’afafine Notes.” ↵

- For an example of conflation, see J. M. Mageo, Theorizing Self in Samoa: Emotions, Genders, and Sexualities (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1998). ↵

- R. P. Gaudio, Allah Made Us: Sexual Outlaws in an Islamic African City (West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009). ↵

- R. Smith Oboler, “Is the Female Husband a Man? Woman/Woman Marriage among the Nandi of Kenya,” Ethnology 19, no. 1 (1980): 69–88. ↵

- R. Morgan and S. Wieringa, Tommy Boys, Lesbian Men, and Ancestral Wives: Female Same-Sex Practices in Africa (Johannesburg, South Africa: Jacana Press, 2005); Gay and Lesbian Coalition of Kenya, “Research on the Lived Experiences of Lesbian, Bisexual and Queer Women in Kenya,” 2016, https://www.icop.or.ke/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Research-on-the-lived-experiences-of-LBQ-women-in-Kenya.pdf. ↵

- I. Amadiume, Male Daughters, Female Husbands: Gender and Sex in an African Society (London: Zed Press, 1987); Kenneth Chukwuemeka Nwoko, “Female Husbands in Igbo Land: Southeast Nigeria,” Journal of Pan African Studies 5, no. 1 (2012): 6982. ↵

- S. Dankwa, “The One Who First Says ‘I Love You’: Love, Seniority, and Relational Gender in Postcolonial Ghana,” in Sexual Diversity in Africa: Politics, Theory, and Citizenship, ed. S. N. Nyeck and M. Epprecht (Montreal, Canada: McGill-Queens University Press, 2013), 170–187; Zanele Muholi, “Thinking through Lesbian Rape,” Agenda: Empowering Women for Gender Equity 18, no. 61 (2004): 116–125, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4066614. ↵

- S. O. Dankwa, Knowing Women: Same Sex Intimacy, Gender, and Identity in Postcolonial Ghana (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021). ↵

- A. della Ragione, “I Femminielli” [in Italian], accessed March 17, 2022, http://www.guidecampania.com/dellaragione/articolo3/articolo.htm#99. ↵

- R. Norton, Mother Clap’s Molly House: The Gay Subculture in England, 1700–1830 (Farnham, Surrey, UK: Heretic Books, 1992). ↵

- M. Foucault, The History of Sexuality, vol. 1, An Introduction (New York: Vintage Books, 1978). ↵

- The profile, slightly edited, is from the website Africa Is a Country, https://africasacountry.com/2020/01/queering-pan-africanism. ↵

- A. Jjuuko, “The Protection and Promotion of LGBTI Rights in the African Regional Human Rights System: Opportunities and Challenges,” in Protecting the Human Rights of Sexual Minorities in Contemporary Africa, ed. Sylvie Namwase and Adrian Jjuuko (Pretoria: Pretoria University Law Press, 2017), https://www.pulp.up.ac.za/latest-publications/179-protecting-the-human-rights-of-sexual-minorities-in-contemporary-africa. ↵

- “African LGBTI Manifesto/Declaration,” Black Looks, posted by Sokari, May 17, 2011, http://blacklooks.org/2011/05/african-lgbti-manifestodeclaration/. The manifesto is also printed in Sokari Ekine and Hakima Abbas, eds., Queer African Reader (Nairobi: Fahamu Books, an imprint of Pambazuka Press, 2013), 52–53 ↵

- Ekine and Abbas, Queer African Reader. ↵

- B. Wainaina, “Conversations with Baba,” TEDxEuston talk, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z5uAoBu9Epg&t=605s. ↵

- Art Attack, “Same Love (remix),” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8EataOQvPII. ↵

- H. Adi, Pan-Africanism: A History (London: Bloomsbury, 2018). ↵

- M. Garvey, The Philosophy and Opinions of Marcus Garvey, Or, Africa for the Africans, comp. Amy Jacques Garvey (1923, 1925; repr., Dover, MA: Majority Press, 1986). ↵

- B. Wainaina, “That name Baldwin, is black, African, ours,” Twitter, March 9, 2014, 6:42 p.m., https://twitter.com/BinyavangaW/status/442792599582035968; Binyavanga Wainaina, “The Baldwin who was a ‘gay icon of freedom,’” Twitter, March 25, 2014, 9:44 p.m., https://twitter.com/BinyavangaW/status/448636702379491329; Binyavanga Wainaina, “James Baldwin wrote new scriptures,” Twitter, February 6, 2014, 7:48 p.m., https://twitter.com/BinyavangaW/status/431590250788294656; “George Bush’s pastor has had more influence on the,” Twitter, January 24, 2014, 10:55 a.m., https://twitter.com/BinyavangaW/status/426745152778944512; Binyavanga Wainaina, “The Jesus of James Baldwin and Martin Luther King is a dead man in Africa,” Twitter, May 4, 2015, 3:13 a.m., https://twitter.com/BinyavangaW/status/595124119127097344. ↵

The way people experience and express themselves sexually and involving biological, erotic, physical, emotional, social, or spiritual feelings and behaviors.

Romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or sexual behavior between persons of the opposite sex or gender.

Refers to social anthropology and cultural anthropology together, focusing on the study of human culture and society.

An account of social life and culture in a particular time and place, written by an anthropologist. The account is based on detailed observations of people interacting in a particular social setting over time.

The range of characteristics pertaining to, and differentiating between, masculinity and femininity. Depending on the context, these characteristics may include biological sex (i.e., the state of being male, female, or an intersex variation), sex-based social structures (i.e., gender roles), or gender identity. Some societies have genders that are in addition to male and female and are neither, such as the hijras of South Asia; these are often referred to as third genders. Some anthropologists and sociologists have described fourth and fifth genders.

In psychology, the qualities, beliefs, personality, looks, or expressions that make up a person (self-identity) or group (particular social category or social group).

The idea that there are only two genders, male and female, and that everyone should and will identify accordingly.

A concept in which individuals are categorized, either by themselves or by society, as neither man nor woman.

Used by sexologists, primarily in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, to refer to homosexuals. Sexual inversion was believed to be an inborn reversal of gender traits: male inverts were inclined to traditionally female pursuits and dress and vice versa for female inverts.

People who use stereotypically gendered clothing and makeup to imitate and often exaggerate gender signifiers and gender roles in an entertainment performance. Drag queens are associated with gay men and gay culture.

A field of critical theory that emerged in the early 1990s out of the fields of lesbian and gay studies and women’s studies. Queer theory seeks to challenge and overturn sex and gender binaries and the normative expectations that support those binaries.

The Maori word meaning a devoted partner of the same sex.

A Hawaiian term used in precolonial times for same-sex relationships between men.

Before the late twentieth century, a term bestowed by anthropologists who were not Native American, or First Nations in Canada, people to broadly identify an Indigenous individual fulfilling one of many mixed-gender roles in a tribe. Anthropologists often applied this term to any male whom they perceived to be homosexual, bisexual, or effeminate by Western social standards, leading to a wide variety of individuals being categorized under what is now considered a pejorative term.

A modern umbrella term used by some Indigenous North Americans to describe Native people in their communities who fulfill a traditional third-gender (or other gender-variant) ceremonial role in their cultures.

A Cherokee term for two-spirit people.

In Zapotec cultures of Oaxaca (southern Mexico), a person who is assigned male at birth but who dresses and behaves in ways otherwise associated with women; the person may be seen as a third gender.

A Zapotec term similar to the Oaxacan muxe describing a male-bodied individual who acts and dresses in feminine ways.

The distress individuals feel if their gender identity does not match their sex assigned at birth.

Behavior or gender expression by an individual that does not match masculine or feminine gender norms. Also called gender nonconformity.

In South America, a gender identity describing people assigned male at birth who take on a feminine gender role and gender expression, especially through the use of feminizing body modifications such as hormone replacement therapy, breast implants, and silicone injections.

A eunuch, intersex, or transgender person. Hijras are officially recognized as a third gender in countries on the Indian subcontinent and considered neither completely male nor female.

The preferred term of members of the hijra community in India, referring to the mythological beings that excel at song and dance.

Individuals born with any of several combinations in sex characteristics, including chromosomes, gonads, sex hormones, or genitals.

In the Philippines, a person who was assigned male at birth but, usually, adopts feminine mannerisms and dresses as a woman. Bakla are often considered a third gender. Many bakla are exclusively attracted to men but are not necessarily gay. Some self-identify as women.

A West Sumatran term for women who dress like men and have relationships with women.

In Thailand, describes a male-to-female transgender person or person of a third gender or an effeminate homosexual male.

Another term for kathoey.

People who identify themselves as having a third-gender or nonbinary role in Samoa, American Samoa, and the Samoan diaspora. It is a recognized gender identity or gender role in traditional Samoan society and an integral part of Samoan culture. Fa’afafine are assigned male at birth and explicitly embody both masculine and feminine gender traits in a way unique to Polynesia.

The word for “in the middle” in Kanaka Maoli (Hawaiian) and Maohi (Tahitian) cultures describing third-gender persons with traditional spiritual and social roles within the culture.

The Japanese term for “young person” (although never used for girls); it is a historical Japanese term indicating an adolescent boy, and in Edo-period Japan, considered as suitable objects of erotic desire for young women, older women, and older men.

The Japanese words for “the ways of teenage and adolescent boys,” respectively.

A Japanese term literally meaning “herbivore men,” describing men who have no interest in getting married or finding a girlfriend. Herbivore men also describes young men who have lost their manliness.

A Nigerian Hausa term meaning “men who act like women.”

Describes the union of two women in marriage in many African cultures, including the Nandi of Kenya.

A Tanala Malagasy term referring to third-gender males who adopt the behavior and roles of women.

A member of a population of homosexual males with markedly feminine gender expression in traditional Neapolitan culture. The plural is femminielli.

A meeting place in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century England, generally taverns, public houses, or coffeehouses, where homosexual men could socialize or meet sexual partners.