Private: Part IV: Prejudice and Health

Chapter 7: LGBTQ+ Health and Wellness

Thomas Lawrence Long; Christine Rodriguez; Marianne Snyder; and Ryan J. Watson

Introduction

The health and wellness of LGBTQ+ and other sexual minority people in the United States is influenced by many factors: access to health care and health insurance; ability for open self-disclosure with a queer-affirming health professional; knowledge about the unique health challenges of LGBTQ+ people, including disease prevention and health promotion; and a sense of self-efficacy about their health, or the confidence that they know how to live a healthy life, along with the intention, necessary knowledge, and resources to do so. According to the Institute of Medicine of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences, LGBTQ+ health can be understood through four lenses:

- Minority stress model—chronic stress that sexual and gender minorities routinely experience can contribute to physical and mental health problems.

- Life-course perspective—events at each stage of life influence subsequent stages, with LGBTQ+ people being particularly vulnerable in adolescence and young adulthood.

- Intersectionality perspective—an individual’s multiple identities and the ways they interact may compromise health so that gender and sexual identity may be complicated, for example, by racial or ethnic identity or economic status. Health disparities are already amplified among racial and ethnic minority populations, which queer sexual orientation is likely to intensify further.

- Social ecology—individuals are surrounded by spheres of influence and support, including families, friends, communities, and society, that shape self-efficacy and health.[1]

In this chapter we keep in mind these four overlapping dimensions while exploring the following topics:

- LGBTQ+ people and the history and culture of medicine.

- Vulnerabilities of LGBTQ+ people across the lifespan and across intersectional identities (including race and ethnicity).

- Transgender people’s health.

- Guidelines for being a smart patient and health care consumer.

History and Culture of Medicine and LGBTQ+ People

LGBTQ+ people often have complicated relationships with medicine, and these relationships have histories that extend back to the 1800s. The philosopher Michel Foucault famously (and controversially) suggested that queer sexualities in the ancient and medieval worlds were judged in an exclusively legal or religious category but that in the 1800s sexualities became medicalized.[2] From this perspective, in historical terms, LGBTQ+ people in Western society went from being criminal or immoral to being mentally ill.

Viewed as a pathology rather than just a moral failing or legal violation, queer sexuality became the object of medicine’s study: What is its cause, and if it is a pathology or disease, how might it be cured? This moment occurred in the second half of the 1800s when medical research and practice had absorbed enormous cultural power and authority through its first modern groundbreaking discoveries, including the development of germ theory, surgical antisepsis, and anesthesia. All things seemed possible to medicine.

Developing Terminology

The term homosexual appears to have been coined by the Austro-Hungarian journalist Karl-Maria Kertbeny (1824–1882) (figure 7.1) in an 1869 pamphlet criticizing a German anti-sodomy law.[3] The term was taken up by the psychiatrist Richard von Krafft-Ebing (1840–1902) in his Psychopathia Sexualis [Mental illnesses related to sex] (1886).[4] The term entered English through a translation of Krafft-Ebing’s work and through the advocacy writing of John Addington Symonds and Havelock Ellis in England. The term bisexual, in contrast, had been used in botany since the 1700s to denote plants with both male and female anatomy (also referred to as hermaphrodite), but was adapted in the late 1800s to denote a person with roughly equivalent attraction to men and women. The term intersex, used as a synonym for homosexual, was adapted in the early twentieth century from biology, where it indicated the possession of both female and male anatomical features, and it is now the term frequently used by people born with ambiguous genitalia.

Theories of Sexual Variation

These attempts to name this unique species of human beings and diagnose what they viewed as sexual pathology, or disease, led physicians, sexologists, and psychiatrists to a search for causality and treatment. David F. Greenberg identifies five explanatory categories that emerged over time: homosexuality as innate, degeneracy theory, Darwinian theory, psychoanalytic theory, and behaviorism.[5]

Nineteenth-century advances in embryology and genetics may have influenced what had often been an assumption since Greco-Roman antiquity that sexuality was innate, leading to a theory of the third sex, which was also encouraged by movements for social tolerance and legal reform. In contrast, proponents of degeneracy theory viewed homosexuality and bisexuality as akin to criminality, alcoholism, and drug addiction. Degeneracy suggests that the gene pool had become exhausted as a result of modern life or personal vice and indulgence inherited from a previous generation. Similarly, the application of Darwinian theory evaluated people and behavior, characterizing homosexual and bisexual people as evolutionary throwbacks, akin to “primitive” peoples whom Europeans had colonized throughout the world and whose sexual mores were at odds with Western notions of morality.

Perhaps no theories of sexual identity have been more influential than psychoanalytic theory and behaviorism. Although various psychodynamic theories were espoused in the late 1800s and early 1900s, Sigmund Freud, often called the father of modern psychoanalysis, postulated that infants are “polymorphous perverse,” deriving pleasure from many parts of their body and regardless of gender. The function of society, for Freud, was to channel pleasure into an acceptable, productive heterosexuality. However, traumas or inner conflicts could arrest a child’s psychosexual development or cause a young adult to regress into homosexuality (for example, an overly attentive mother and distant father for boys). The role of psychotherapy was to expose the trauma or conflict and allow growth toward heterosexuality to resume. Nonetheless, Freud was less inclined to view homosexuality as a sickness than as a form of psychosexual immaturity. Behaviorism, in contrast, has been inclined to view sexual orientation generally as a learned behavior, which means that homosexuality can be unlearned.[6] Whereas psychoanalytic theory prefers talk therapy, behaviorism has tended to employ rewards and punishments to “reprogram” sexual behavior, including electroshocks and hormone injections. So-called gay conversion therapy, the subject of increasing legal rejection by states today, has a decades-old history.

Emerging Self-Care

Throughout the twentieth century the medical establishment in the United States generally considered queer sexualities as mental illnesses. However, early descriptive research by Alfred Kinsey and his colleagues disclosed both a surprising number of self-identified LGB persons and a fluid spectrum of human sexual response. What they called a “heterosexual-homosexual rating scale” identified a range from exclusively heterosexual (0) to equally heterosexual and homosexual (3), otherwise known as bisexual, to exclusively homosexual (6). This scale was applied to each individual according to the participants’ sexual behavior and psychic reactions—that is, thoughts, feelings, and fantasies.[7]

It is no wonder, then, that by the 1960s and the emergence of the gay rights movement, many LGBTQ+ people had come to distrust the medical establishment. Health care providers often either exhibited hostility or acknowledged ignorance about the unique health concerns of LGBTQ+ people.[8] Many gay men and lesbians in particular had come to reject the notion of their sexual orientation as a pathology and had begun to seek the rare health care providers who were affirming of their sexualities. Feminists and the women’s movement had shown how this might be done with health collectives, like the one in Boston that produced the book Our Bodies, Ourselves, part of a movement in the United States in the late 1960s and early 1970s for homegrown self-published self-help books.[9] One groundbreaking book for queer people included chapters on alcohol safety, venereal diseases (now called sexually transmitted infections), and other health topics, many of which had been previously published in local queer newspapers and magazines.[10] In major urban areas, health clinics for LGBTQ+ people formed to serve this vulnerable population.[11]

When the first published reports of an infectious epidemic that would come to be called acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) appeared in 1981, queer communities were wary of uncertain medical explanations and advice, aware of the stigmatization of their sexualities that was now exacerbated by AIDS, but also more prepared for community organizing around health concerns. Grassroots organizations at least in large or midsize metropolitan areas—like New York’s GMHC (Gay Men’s Health Crisis) and Tidewater AIDS Crisis Taskforce of Norfolk, Virginia—advocated, educated, and cared for people infected with HIV. Chapters of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) blossomed in cities, particularly New York and San Francisco, bringing direct-action demonstrations against government and medical inaction. AIDS activists changed the ways that the U.S. medical establishment conducted research and delivered care by insisting on the participation of people living with AIDS in decisions about drug approvals and treatment.[12]

Medicine and the History of Transgender Care

The celebrity of Christine Jorgensen (figure 7.2), who began her physical transition from male to female in the early 1950s and who led a bold public life as a writer, lecturer, and entertainer, brought the transgender experience to wide attention.[13] Beginning in 1965, Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore was the first American medical school to study and perform what was called sex reassignment surgery (now more aptly known as gender-affirming surgery), or in popular parlance, sex change operations. However, despite this pioneering role, the Johns Hopkins clinic ended the practice in 1978, in part because of flawed transphobic follow-up research. Only recently has it resumed its transgender and gender-affirming care.[14] In the first decade and a half of the twenty-first century, almost forty thousand patients sought transgender care, with 11 percent of them seeking gender-affirming surgery and an increasing percentage using health insurance rather than out-of-pocket payments as had been typical in the past.[15]

Medicine’s relationship to LGBTQ+ people has been complicated enough over the last century and a half, but considering a person’s place in the human lifespan and intersectional identities makes it even more so. We explore these considerations next.

Vulnerabilities across the Lifespan and across Intersectional Identities

Decades of research have indicated that LGBTQ+ populations face a disproportionate burden of health problems and stigma, including higher levels of depression, lower self-esteem, compromised academic achievement, and more substance use.[16] These disparities are documented across the lifespan, from childhood to young adulthood and even into late adulthood.[17] Researchers have identified minority stress, or sexuality- and gender-related stressors, as the mechanism through which these health problems can be explained.[18]

Minority Stress Model

Being a marginalized or minority person in a society produces personal and group stress, sometimes invisible but always with both psychological and physiological effects. The Institute of Medicine report proposed the minority stress model as a strong framework to understand health disparities among LGBTQ+ populations. In particular, the report highlights how minority stress has been found to affect the day-to-day lives and health of LGBTQ+ individuals across the lifespan.[19] This minority stress can be distal (e.g., victimization from others because of a sexual minority identity) or proximal (e.g., concealment of sexual identity, internalized homophobia). Therefore, strategies to promote health and well-being should consider multiple types of stressors.

Intersecting Identities

In addition to minority stress, the Institute of Medicine recommended a focus on intersectionality as an imperative consideration for researchers, clinicians, and other stakeholders invested in LGBTQ+ health.[20] Intersectionality at its broadest meaning proposes that race, ethnicity, ability status, and other oppressed identities can amplify LGBTQ+ health issues.[21] In addition to being aware how oppressed and intersecting identities can compound health outcomes, researchers are increasingly measuring and considering all demographic characteristics among LGBTQ+ youth to better understand how multiple identities (e.g., being Black, gay, and residing in the U.S. South) might be related to the holistic LGBTQ+ experience. For example, a study collected data from 17,112 LGBTQ+ youth across the United States and documented twenty-six distinct sexual and gender identities.[22] Additionally, youth who were transgender and nonbinary were more likely than cisgender youth to identify with an “emerging sexual identity label,” such as pansexual (figure 7.3). These patterns also differed by ethnoracial identity, suggesting that youth of color are using different terms, compared with their white counterparts, to describe their sexual attractions and gender identities. The next step is to better understand how intersecting identities may be uniquely associated with health outcomes, given that a large focus of research has focused on disease prevention and health promotion among LGBTQ+ populations. The Institute of Medicine also points out that LGBTQ+ couples and their children are less likely to have adequate health insurance, which is usually provided through employers, especially when they are unemployed or underemployed.[23]

Disease Prevention and Health Promotion

Recent research on health disparities finds that the gap in disparities between some LGBTQ+ and heterosexual youth continues to grow across a number of outcomes.[24] Emerging research has moved beyond documenting these disparities to examining the risk and protective factors that may help prevent disease and promote health among LGBTQ+ people.

With respect to LGBTQ+ youth, research has consistently documented family and parent support to be the strongest buffer against negative health experiences, above and beyond other support systems. In addition to families, a number of other support systems are known to protect against negative health (and thus disease later in life), such as school-based clubs, supportive peers, and supportive policies and laws.[25] The protective role of these support systems extends into young adulthood and across a lifespan, but the magnitude by which certain supports (e.g., school peers) affect LGBTQ+ health may change.

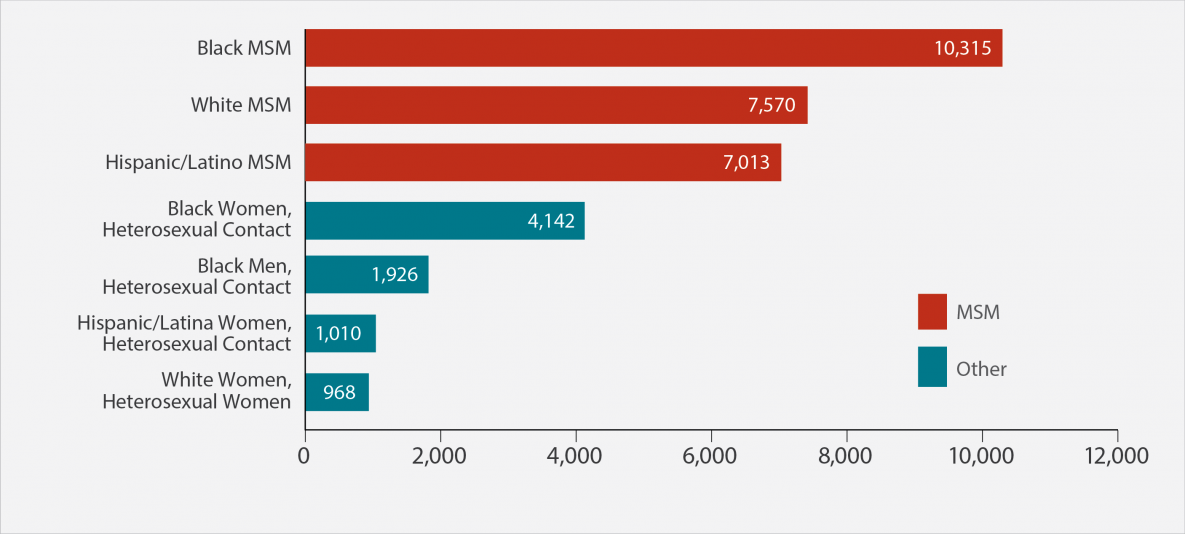

Among older LGBTQ+ adults, there has been a strong focus on sexually transmitted disease and HIV prevention. Given HIV’s disproportionate burdens on the LGBTQ+ community, and in particular the disproportionate impact on African American men who have sex with men, research funding and attention have focused on reducing this stark disparity (figure 7.4). Medical advancements in preventing HIV have proliferated in the recent past, and one method in particular, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), has been the focus of many studies. However, a vexing dilemma exists: although there is a drug that can prevent HIV infection, why aren’t more men who have sex with men (and LGBTQ+ individuals) taking the drug? After all, Tony Kirby and Michelle Thornber-Dunwell find that the rates of HIV acquisition in the United States are still high and similar to the rates in other countries. Researchers continue to consider how stigma, a history of medical mistrust, and other factors might thwart the uptake of lifesaving drugs that prevent HIV among LGBTQ+ populations.[26]

See table 7.1 for a summary of the critical health concerns over the life course.

Table 7.1 Health concerns across the lifespan

| Life stage | Health concerns |

| Adolescence | HIV infection, particularly among Black or Latino men who have sex with men; depression, suicidal ideation, suicide attempts; smoking, alcohol, substance use; homelessness; violence, bullying, harassment |

| Early to midadulthood | Mood and anxiety disorders; using preventive health resources less frequently; smoking, alcohol, substance use |

| Later adulthood | Long-term hormone use among transgender people; HIV infection; stigma, discrimination, violence in health care institutions (e.g., nursing homes). The research literature also suggests that older LGBTQ+ adults may possess a high degree of resilience, having weathered the difficulties of adolescence and earlier adulthood |

Source: Institute of Medicine, The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding (Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2011).

A long history of health professionals’ insensitivity or even hostility to LGBTQ+ people, as described in the beginning of this chapter, continues to have real-life consequences. Disparities are particularly evident among transgender people, who are a uniquely vulnerable population and whose health and wellness concerns we discuss next.

Transgender and Gender-Nonconforming Health Care

The transgender and gender-nonconforming community has suffered, often in silence. Numerous studies have depicted the barriers these patients face with respect to health care, which include mistreatment by health care providers and providers’ discomfort or inexperience regarding patient’s health care needs, as well as patients’ lack of adequate insurance coverage for health care services.[27] Owing to these barriers, transgender and gender-nonconforming patients are often left to navigate health care on their own.

For example, the National Center for Transgender Equality reported that 33 percent of respondents who had seen a health care provider in the preceding year suffered at least one negative experience related to being transgender, and 23 percent of respondents did not even seek a medical provider when they needed one for fear of being mistreated. Additionally, a staggering 39 percent of respondents experienced psychological distress, and 40 percent have attempted suicide in their lifetimes, which is nearly nine times the 4.6 percent rate of the general population.[28] Seeking routine or preventive physical and mental health care, let alone transition-related services for those who seek to transition, is difficult.

Incidence and Prevalence

Several attempts have been made to determine how many Americans identify as transgender.[29] A 2016 estimate postulates that 0.6 percent of the population, or 1.4 million Americans, are transgender.[30] However, the gender construct is complex, and more rigorous epidemiological studies are needed on a global scale to delineate the incidence (percentage of the population) and prevalence (total number of people) of this experience. Historically, transgender and gender-nonconforming individuals have been marginalized, and the disparities discussed earlier in this chapter may instill a sense of fear within the community, thus leading to greater difficulty in obtaining an accurate estimate. Additionally, cultural differences among societies shape the behavioral expressions of gender identities, masking gender dysphoria.[31] For instance, certain cultures may revere and consider as sacred such gender-nonbinary behaviors, leading to less stigmatization.[32]

Moreover, as the literature suggests, the prevalence of gender dysphoria is unknown. There has been great controversy within the transgender and gender-nonconforming community regarding this diagnosis because in earlier years the phenomenon was deemed psychopathological.[33] On the one hand, gender nonconformity refers to “the extent to which a person’s gender identity, expression, or role differs from the cultural norms that designate for people of a particular sex.”[34] On the other hand, gender dysphoria, first described by N. M. Fisk in 1974, is the “discomfort or distress that is caused by a discrepancy or incongruence with a person’s gender identity and that very same person’s sex that was assigned at birth.”[35] Therefore, not every transgender and gender-nonconforming individual experiences gender dysphoria. As a result, the World Professional Association of Transgender Health released a statement in 2010 that urged the depsychopathologization of gender nonconformity worldwide.[36] The goal of the health care professional is thus to assist transgender and gender-nonconforming patients who suffer from gender dysphoria by affirming their gender identity and collaboratively investigating the array of options that are at their disposal for expression of their gender identity.

Therapeutic Options for Transgender and Gender-Nonconforming Patients

An array of therapeutic options must be considered when collaboratively working with transgender and gender-nonconforming patients. Transition, for those who seek it, does not follow a linear model but is, rather, an individualized process based on the patient’s specific needs. Interventions and their sequence differ from person to person. A collaborative approach between the health care professional and patient is of the utmost importance. Additionally, a multidisciplinary approach, one that encompasses primary care providers, mental health clinicians, surgeons, and speech pathologists, results in the best outcomes. The following lists therapeutic options that a transgender and gender-nonconforming patient may undertake:

- Changing gender expression or role, whether living full-time or part-time in the gender expression that aligns with the current gender identity. This may involve chest binding to create a flat chest contour, padding of the hips and buttocks, genital tucking, wearing gaff underwear, or wearing a prosthesis.

- Changing a name and gender marker on identity documents.

- Seeking psychotherapy to understand and investigate the constructs of gender, such as gender identity, gender role, gender attribution, and gender expression. Psychotherapy may also address the positive or negative impacts of such feelings as stigma and address internalized transphobia, if present.

- Undergoing gender-affirming hormone therapy to either feminize or masculinize the patient’s body.

- Choosing gender-affirming surgeries to alter primary or secondary sex characteristics.

- Finding peer-support groups and community organizations that provide social support, as well as advocacy.

- Attending speech or voice and communication therapy that facilitates comfort with gender identity or expression and ameliorates the stress associated with developing verbal and nonverbal behaviors or cues when interacting with others.

- Removing hair through laser treatments, electrolysis, waxing, epilating, or shaving.

The options may seem overwhelming to review, but it is the goal of the health care professional to assist the patient through the journey, regardless of what therapeutic options the patient ultimately chooses. Access to those services requires that the transgender person live in an area where they are available and have adequate health insurance, which is usually provided by employers. Transgender people, particularly trans people of color, however, are less likely to be employed than cisgender LGB people, thus are often deprived of the health insurance that they need.

Criteria for Gender-Affirming Hormone Therapy

Gender-affirming hormone therapy consists of the administration of exogenous endocrine agents to elicit feminizing or masculinizing changes. While some transgender and gender-nonconforming patients may seek maximum changes, others may be content with a more androgynous presentation. The fluidity of this construct should not be minimized, because hormonal therapy must be individualized on the basis of a patient’s goals and thorough understanding of the risks and benefits of medications and an in-depth review of a patient’s other existing medical conditions. Furthermore, initiation of hormonal therapy may

be undertaken after a psychosocial assessment has been conducted and informed consent has been obtained by a qualified health professional. . . . The criteria for gender-affirming hormone therapy are as follows:

- Persistent, well-documented gender dysphoria;

- Capacity to make a fully informed decision and to consent for treatment;

- Age of majority in a given country . . . ;

- If significant medical or mental health concerns are present, they must be reasonably well-controlled.[37]

Common agents used for feminization regimens are estrogen and antiandrogens, and the common agent used for masculinization regimens is testosterone. Progestins are controversial in feminizing regimens, and clinicians can cite only anecdotal evidence for the hormone’s use in full breast development. A clinical comparison of feminizing regimens with and without the use of progestins found that these agents did not enhance breast growth or reduce serum levels of free testosterone.[38] Additionally, progestins’ adverse effects outweigh their benefits because depression, weight gain, and lipid changes have been seen with these agents.[39] However, progestins do play a role in masculinizing regimens and when used in early stages of hormonal therapy assist in the cessation of menses.

Physical Effects of Gender-Affirming Hormone Therapy

A thorough discussion regarding the physical effects of gender-affirming hormone therapy between the health care professional and the patient is warranted. Using endocrine agents to achieve congruency with a patient’s gender identity will induce physical changes, which may be reversible or irreversible. Most physical changes occur within two years, with several studies estimating the process to span five years. The length of time attributed to such changes is unique to each individual. Tables 7.2 and 7.3 outline the estimated effects and the course of such changes.

Table 7.2 Effects of gender-affirming hormone therapy with masculinizing agents

| Effect | Onset (months) |

| Acne | 1–6 |

| Facial and body hair growth | 6–12 |

| Scalp hair loss | 6–12 |

| Increased muscle mass | 6–12 |

| Fat redistribution | 1–6 |

| Cessation of menses | 1–6 |

| Clitoral enlargement | 1–6 |

| Vaginal atrophy | 1–6 |

| Deepening of voice | 6–12 |

Table 7.3 Effects of gender-affirming hormone therapy with feminizing agents

| Effect | Onset (months) |

| Softening of the skin | 3–6 |

| Decreased libido | 1–3 |

| Decreased spontaneous erections | 1–3 |

| Decreased muscle mass | 3–6 |

| Decreased testicular volume | 6–12 |

| Decreased terminal hair growth | 6–12 |

| Breast growth | 3–6 |

| Fat redistribution | 3–6 |

| Voice changes | None |

Because of the masculinizing or feminizing effects of endocrine agents used in transitioning, the coming out process for someone who identifies as transgender or gender nonconforming may be challenging and may differ from the coming out process of LGB individuals. LGB individuals may keep their sexual orientation concealed, but the effects of hormonal agents on the transgender person are noticeable to others. Transgender and gender-nonconforming individuals may have to come out during social interactions, unless they wish to relocate to a new area, where they may choose not to disclose their transgender identity, often referred to in the community as “living stealth.”

The coming out process may seem daunting to endure and may encompass numerous challenges. Those lacking support or who have been “mistreated, harassed, marginalized, defined by surgical status, or repeatedly asked probing personal questions may . . . [experience] significant distress.”[40] Additionally, the persistent and chronic nature of these microaggressions have led some researchers to apply the minority stress model to transgender and gender-nonconforming individuals.[41] Such experiences create a potential for increase in the rate of certain health care conditions, such as clinical depression and anxiety and their somatization, or conversion to physical symptoms.[42]

Transgender people, like all other LGBTQ+ people, need to learn how to become informed consumers of health care services and make informed choices about their physical and mental well-being. The next section explains how to become such a knowledgeable patient.

Being a Smart Patient and Health Care Consumer

As noted throughout this chapter, LGBTQ+ individuals encounter more discrimination in health care compared with the heterosexual population. While some evidence shows that negative experiences for some LGBTQ+ persons are decreasing, discrimination continues. Lack of health care provider education in culturally inclusive LGBTQ+ communication and care is frequently noted as a contributing factor for health professionals’ discrimination. The shortage of educated practitioners and amount of practitioner bias have caused many LGBTQ+ persons to either delay or avoid seeking health care services. A primary reason attributed for this delay or avoidance is that LGBTQ+ individuals often feel invisible to their providers and have experienced discrimination in previous encounters.[43]

Other factors also contribute to the negative health care experiences of LGBTQ+ individuals. A provider whose value system, religious beliefs, and political party affiliation are hostile to LGBTQ+ people may have difficulty providing the respectful and affirming care that LGBTQ+ persons are entitled to. For LGBTQ+ people to receive respectful and culturally inclusive, patient-centered care from their providers, they must take it on themselves to be informed health care consumers, practice self-advocacy, and shop wisely for providers who are LGBTQ+ affirming. Self-advocacy is essential to optimizing access to quality health services.

Health Care Providers

The teaching of medical and nursing students about health issues unique to the LGBTQ+ population is inconsistent among education programs for health care providers. An emerging body of research finds a need for more education to better meet the requirements of LGBTQ+ patients. In one study, for example, U.S. medical schools were found to provide only an average of five hours of LGBTQ+ education throughout the curriculum. Baccalaureate nursing programs in another study spent only an average of a little over two hours teaching content about LGBTQ+ health topics. Less is known about the extent to which other health provider education programs cover this content. During a health care clinical experience, LGBTQ+ individuals often encounter health care providers who lack a basic understanding of LGBTQ+ cultures, terminology, and culturally inclusive care.[44]

Locating a health care facility that affirms LGBTQ+ people can be difficult but is not impossible. Some national organizations provide resources for LGBTQ+ persons and health care providers. For example, the Human Rights Campaign, the largest national LGBTQ+ civil rights organization with over three million members, has a benchmarking tool, the Healthcare Equality Index, to recognize the health care facilities with policies and procedures for equity and inclusion of LGBTQ+ patients, visitors, and employees. Health care facilities evaluated by the index are available in its directory. An agency must reapply every year to demonstrate that it meets the current standards outlined by the Human Rights Campaign.[45]

Another organization, GLMA (Gay and Lesbian Medical Association), advances health care equality for LGBTQ+ people and has an extensive directory of health care providers across the United States that are LGBTQ+ affirming. The GLMA published guidelines that offer recommendations for practitioners to consider when caring for LGBTQ+ clients. The National LGBT Health Education Center, a program of the Fenway Institute, also has excellent resources to help educate providers.[46] Both organizations provide valuable resources and are worth mentioning to a provider who lacks sufficient knowledge to provide culturally inclusive care for LGBTQ+ persons. Organizations and coalitions that support LGBTQ+ health are listed in table 7.4. All provide free publications and resources for the LGBTQ+ person and health care providers.

Table 7.4 LGBTQ+ education and advocacy organizations

| GLMA Health Professionals Advancing LGBTQ Equality | http://www.glma.org/ |

| Association of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender Addiction Professionals and Their Allies | http://www.nalgap.org/ |

| World Professional Association for Transgender Health | https://www.wpath.org/ |

| Center of Excellence for Transgender Health | http://transhealth.ucsf.edu/ |

| National LGBT Cancer Network | https://cancer-network.org/ |

| Trevor Project | https://www.thetrevorproject.org/ |

| CenterLink: Community of LGBT Centers | https://www.lgbtcenters.org/ |

| Fenway Health | https://fenwayhealth.org/the-fenway-institute/ |

| Howard Brown Health | https://howardbrown.org/ |

| Los Angeles LGBT Center | https://lalgbtcenter.org/ |

| Mazzoni Center LGBTQ Health and Well-Being | https://www.mazzonicenter.org/ |

| Callen-Lorde | https://callen-lorde.org/ |

| LGBT Health Link | https://www.lgbthealthlink.org/ |

Informed Health Care Consumers

When navigating a system in which not all providers understand or practice care that includes LGBTQ+ people, LGBTQ+ individuals need to know what questions to ask when visiting their provider. Although it is important to be true to yourself and disclose your sexual identity to your provider so you can receive the most holistic care possible, not all LGBTQ+ persons feel comfortable disclosing this information, particularly to a new health care provider with whom they have not yet established a trusting relationship. The Institute of Medicine has recommended including sexual orientation and gender identity data in electronic health records so that more health care facilities will ask patients for this information.[47] Ultimately, however, LGBTQ+ persons must decide for themselves when and to whom to disclose their LGBTQ+ identity.

Before visiting a provider, consider calling the office to ask if they provide inclusive care for LGBTQ+ patients. Bring a friend or partner to the visit for support if you are uncomfortable meeting with the health care provider. Health care providers must adhere to laws, policies, and ethical codes to keep your information private. Although a health care provider may ask about sexual orientation and gender identity, LGBTQ+ persons also have the right to request that the provider not enter their sexual orientation and gender identity into the medical record.

Paying Attention to Special Health Issues

Providers must understand health care issues common in the LGBTQ+ population and explore whether their patients have any of these risk factors. GLMA has created ten resource sheets for LGBTQ+ persons, each one addressing one of the top health concerns to discuss with a health care provider. Although not all these health issues apply to every person, it is essential to be aware that these health topics are more common among LGBTQ+ people. Several health topics are relevant to all LGBTQ+ groups, and others pertain more to one group. For example, research has identified that depression, tobacco and alcohol use, sexually transmitted diseases (including human papillomavirus and HIV/AIDS), and certain cancers are greater health risks in the LGBTQ+ population. Moreover, the risk of illicit use of injectable silicone is a more significant concern among transgender women. Other health issues are more common within certain groups, such as breast and gynecological cancers among lesbians and male-to-female transgender persons. In addition to the risk of HIV/AIDS among men who have sex with men, they also have a higher incidence of and mortality from prostate, anal, and colon cancer.[48]

Minimizing risk factors for these acute and chronic illnesses is essential to maintaining health. The LGBT Health Link is a network for health equity and offers very practical advice for things that LGBTQ+ people can do to improve their wellness. Recommendations include how to search for insurance options, practice preventive care, seek mental health support, adopt a healthier lifestyle, and practice safer sex.[49]

The resources provided in this section support LGBTQ+ individuals to advocate for themselves when seeking health care services, particularly from providers who are not well educated about LGBTQ+ health issues or who do not demonstrate culturally inclusive and affirming behaviors. Although health care providers are responsible for establishing a trusting relationship with their patients, this does not consistently occur in every health care setting. When a health care provider demonstrates genuine concern and respect for an LGBTQ+ individual in a practice not restricted to a fifteen-minute office visit, then there is greater opportunity for individualized, holistic, patient-centered care.

Becoming a smarter LGBTQ+ health consumer requires being aware of the community’s complex history with medicine, understanding the unique health issues involved, and recognizing health risks and changes that occur over the course of life.

Media Attributions

- Figure 7.2. © Maurice Seymour is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 7.3. © kiwineko14 is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 7.4. is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Institute of Medicine, The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding (Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2011). ↵

- M. Foucault, The History of Sexuality, vol. 1, An Introduction, trans. R. Hurley (New York: Vintage Books, 1978), 43. ↵

- J.-C. Feray, M. Herzer, and G. W. Peppel, “Homosexual Studies and Politics in the 19th Century: Karl Maria Kertbeny,” Journal of Homosexuality 19 (2010): 23–48. ↵

- R. von Krafft-Ebing, Psychopathia Sexualis. Eine Klinisch-Forensische Studie (Stuttgart, Germany: Ferdinand Enke, 1886). ↵

- D. F. Greenberg, The Construction of Homosexuality (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988). ↵

- Greenberg, The Construction of Homosexuality. ↵

- A. C. Kinsey, W. B. Pomeroy, and C. E. Martin, Sexual Behavior in the Human Male (Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders, 1948), 638. ↵

- K. Batza, Before AIDS: Gay Health Politics in the 1970s (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018). ↵

- K. Davis, The Making of Our Bodies, Ourselves: How Feminism Travels across Borders (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007). ↵

- K. Jay and A. Young, eds., After You’re Out: Personal Experiences of Gay Men and Lesbian Women (New York: Links, 1975). ↵

- A. J. Martos, P. A. Wilson, and I. H. Meyer, “Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Health Services in the United States: Origins, Evolution, and Contemporary Landscape,” PloS One 12, no. 7 (2017): e0180544. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0180544. ↵

- J.-M. Andriote, Victory Deferred: How AIDS Changed Gay Life in America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999). ↵

- J. J. Meyerowitz, How Sex Changed: A History of Transsexuality in the United States (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002); J. Meyerowitz, “Transforming Sex: Christine Jorgensen in the Postwar U.S.,” OAH Magazine of History 20, no. 2 (2006): 16–20. ↵

- Z. Ford, “Johns Hopkins to Resume Gender-Affirming Surgeries after Nearly 40 Years,” Think Progress, October 18, 2016, https://thinkprogress.org/johns-hopkins-transgender-surgery-5c9c428184c1/. ↵

- C. Tantibanchachai, “Study Suggests Gender-Affirming Surgeries Are on the Rise, Along with Insurance Coverage,” Hub (Johns Hopkins University), February 28, 2018, https://hub.jhu.edu/2018/02/28/gender-affirming-reassignment-surgeries-increase/. ↵

- K. I. Fredriksen-Goldsen, H. J. Kim, S. E. Barkan, A. Muraco, and C. P. Hoy-Ellis, “Health Disparities among Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Older Adults: Results from a Population-Based Study,” American Journal of Public Health 103, no. 10 (2013): 1802–1809; Institute of Medicine, The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People; S. L. Reisner, J. M. White, J. B. Bradford, and M. J. Mimiaga, “Transgender Health Disparities: Comparing Full Cohort and Nested Matched-Pair Study Designs in a Community Health Center,” LGBT Health 1, no. 3 (2014): 177–184; S. T. Russell and J. N. Fish, “Mental Health in Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Youth,” Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 12 (2016): 465–487. ↵

- For childhood, see J. G. Kosciw, N. A. Palmer, and R. M. Kull, “Reflecting Resiliency: Openness about Sexual Orientation and/or Gender Identity and Its Relationship to Well-Being and Educational Outcomes for LGBT Students,” American Journal of Community Psychology 55, nos. 1–2 (2015): 167–178; for young adulthood, see C. Ryan, S. T. Russell, D. Huebner, R. Diaz, and J. Sanchez, “Family Acceptance in Adolescence and the Health of LGBT Young Adults,” Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing 23, no. 4 (2010): 205–213; and R. J. Watson, J. Veale, and E. Saewyc, “Disordered Eating among Transgender Youth: Probability Profiles from Risk and Protective Factors,” International Journal of Eating Disorders 50 (2017): 512–522, https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22627; and for late adulthood, see K. I. Fredriksen-Goldsen, “Promoting Health Equity among LGBT Mid-Life and Older Adults: Revealing How LGBT Mid-Life and Older Adults Can Attain Their Full Health Potential,” Generations 38, no. 4 (2014): 86–92. ↵

- I. H. Meyer, “Prejudice, Social Stress, and Mental Health in Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Populations: Conceptual Issues and Research Evidence,” Psychological Bulletin 129, no. 5 (2003): 674–679. ↵

- Institute of Medicine, The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People. ↵

- Institute of Medicine, The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People. ↵

- M. C. Parent, C. DeBlaere, and B. Moradi, “Approaches to Research on Intersectionality: Perspectives on Gender, LGBT, and Racial/Ethnic Identities,” Sex Roles 68, nos. 11–12 (2013): 639–645. ↵

- R. J. Watson, C. Wheldon, and R. M. Puhl, “Evidence of Diverse Identities in a Large National Sample of Sexual and Gender Minority Adolescents,” Journal of Research on Adolescence 30 (2020): 431–442, https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12488. ↵

- Institute of Medicine, The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People. ↵

- See, e.g., R. J. Watson, N. Lewis, J. Fish, C. Goodenow, “Sexual Minority Youth Continue to Smoke Cigarettes Earlier and More Often than Heterosexual Peers: Findings from Population-Based Data,” Drug and Alcohol Dependence 183 (2018): 64–70, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.11.025. ↵

- For family and parent support, see S. Snapp, R. J. Watson, S. T. Russell, R. Diaz, and C. Ryan, “Social Support Networks for LGBT Young Adults: Low Cost Strategies for Positive Adjustment,” Family Relations 64, no. 3 (2015): 420–430, https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12124; for school-based clubs, see V. P. Poteat, J. R. Scheer, R. A. Marx, J. P. Calzo, and H. Yoshikawa, “Gay-Straight Alliances Vary on Dimensions of Youth Socializing and Advocacy: Factors Accounting for Individual and Setting-Level Differences,” American Journal of Community Psychology 55, nos. 3–4 (2015): 422–432; for supportive peers, see R. J. Watson, A. H. Grossman, and S. T. Russell, “Sources of Social Support and Mental Health among LGB Youth,” Youth and Society 51 (2019): 30–48, https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X16660110; and for supportive policies and laws, see M. L. Hatzenbuehler, K. M. Keyes, and D. S. Hasin, “State-Level Policies and Psychiatric Morbidity in Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Populations,” American Journal of Public Health 99, no. 12 (2009): 2275–2281. ↵

- For African American men, see V. M. Mays, S. D. Cochran, and A. Zamudio, “HIV Prevention Research: Are We Meeting the Needs of African American Men Who Have Sex with Men?,” Journal of Black Psychology 30, no. 1 (2004): 78–105; for PrEP, see S. A. Golub, K. E. Gamarel, H. J. Rendina, A. Surace, and C. L. Lelutiu-Weinberger, “From Efficacy to Effectiveness: Facilitators and Barriers to PrEP Acceptability and Motivations for Adherence among MSM and Transgender Women in New York City,” AIDS Patient Care and STDs 27, no. 4 (2013): 248–254; for U.S. rates of HIV acquisition, see T. Kirby and M. Thornber-Dunwell, “Uptake of PrEP for HIV Slow among MSM,” Lancet 383, no. 9915 (2014): 399–400; and for other factors, see J. T. Parsons, H. J. Rendina, J. M. Lassiter, T. H. Whitfield, T. J. Starks, and C. Grov, “Uptake of HIV Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) in a National Cohort of Gay and Bisexual Men in the United States: The Motivational PrEP Cascade,” Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 74, no. 3 (2017): 285–292. ↵

- K. Konsenko, L. Rintamaki, S. Raney, and K. Maness, “Transgender Patient Perceptions of Stigma in Health Care Contexts,” Medical Care 46 (2013): 647–653; T. Poteat, D. German, and D. Kerrigan, “Managing Uncertainty: A Grounded Theory of Stigma in Transgender Health Encounters,” Social Science and Medicine 84 (2013): 22–29; A. Radix, C. Lelutiu-Weinberger, and K. Gamarel, “Satisfaction and Healthcare Utilization of Transgender and Gender Non-conforming Individuals in NYC: A Community-Based Participatory Study,” LGBT Health 103, no. 10 (2014): 1820–1829; C. G. Roller, C. Sedlak, and C. B. Drauker, “Navigating the System: How Transgender Individuals Engage in Health Care Services,” Journal of Nursing Scholarship 47 (2015): 417–424; N. Sanchez, J. Sanchez, and A. Danoff, “Health Care Utilization, Barriers to Care, and Hormone Usage among Male-to-Female Transgender Persons in New York City,” American Journal of Public Health 99 (2009): 713–719; J. M. Sevelius, E. Patouhas, J. G. Keatley, and M. O. Johnson, “Barriers and Facilitators to Engagement and Retention in Care among Transgender Women Living with Human Immunodeficiency Virus,” Annals of Behavioral Medicine 47, no. 1 (2014): 5–16. ↵

- S. E. James, J. L. Herman, S. Rankin, M. Keisling, L. Mottet, and M. Ana, The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey (Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality, 2016). ↵

- Institute of Medicine, The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People; K. J. Zucker and A. A. Lawrence, “Epidemiology of Gender Identity Disorder: Recommendations for the Standards of Care of the World Professional Association for Transgender Health,” International Journal of Transgenderism 11 (2009): 8–18. ↵

- A. R. Flores, J. L. Herman, G. J. Gates, and T. N. T. Brown, How Many Adults Identify as Transgender in the United States? (Los Angeles, CA: Williams Institute, 2016), https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/How-Many-Adults-Identify-as-Transgender-in-the-United-States.pdf. ↵

- E. Coleman, W. Bockting, M. Botzer, P. Cohen-Kettenis, G. DeCuypere, J. Feldman, L. Fraser, et al., “Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender-Nonconforming People, Version 7,” International Journal of Transgenderism 13, no. 4 (2012): 165–232. ↵

- E. Coleman, P. Colgan, and L. Gooren, “Male Cross-Gender Behavior in Myanmar (Burma): A Description of the Acault,” Archives of Sexual Behavior 21, no. 3 (1992): 313–321; S. J. Kessler and W. McKenna, Gender: An Ethnomethodological Approach (New York: Wiley, 1978); A. Wilson, “How We Find Ourselves: Identity Development and Two-Spirit People,” Harvard Educational Review 66 (1996): 303–317. ↵

- P. R. McHugh, “Psychiatric Misadventures,” American Scholar 61 (1992): 497–510. ↵

- Coleman et al., “Standards of Care,” 168. ↵

- N. M. Fisk, “Gender Dysphoria Syndrome—the Conceptualization That Liberalizes Indications for Total Gender Reorientation and Implies a Broadly Based Multi-dimensional Rehabilitative Regimen,” Western Journal of Medicine 120 (1974): 386–391; American Psychological Association, Definitions Related to Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, https://www.apa.org/pi/lgbt/resources/sexuality-definitions.pdf. ↵

- WPATH Board of Directors, “WPATH De-Psychopathologisation Statement,” released May 26, 2010, https://www.wpath.org/policies. ↵

- Coleman et al., “Standards of Care,” 187. ↵

- W. Meyer, A. Webb, C. Stuart, J. Finkelstein, B. Lawrence, and P. Walker, “Physical and Hormonal Evaluation of Transsexual Patients: A Longitudinal Study,” Archives of Sexual Behavior 15, no. 2 (1986): 121–138. ↵

- W. J. Meyer III, A. Webb, C. A. Stuart, J. W. Finkelstein, B. Lawrence, and P. A. Walker, “Physical and Hormonal Evaluation of Transsexual Patients: A Longitudinal Study,” Archives of Sexual Behavior 15 (1986): 121–138; V. Tangpricha, S. H. Ducharme, T. W. Barber, and S. R. Chipkin, “Endocrinologic Treatment of Gender Identity Disorders,” Endocrine Practice 9 (2003): 12–21. ↵

- l. m. dickey, D. H. Karasic, and N. G. Sharon, “Mental Health Considerations with Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Clients,” in Guidelines for the Primary and Gender-Affirming Care of Transgender and Gender Nonbinary People, ed. M. B. Deutsch (San Francisco, CA: Center of Excellence for Transgender Health, 2016), https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/mental-health. ↵

- M. L. Hendricks and R. J. Testa, “A Conceptual Framework for Clinical Work with Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Clients: An Adaptation of the Minority Stress Model,” Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 43 (2012): 460–467; Institute of Medicine, The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People. ↵

- W. O. Bockting, M. H. Miner, R. E. Swinburne Romine, A. Hamilton, and E. Coleman, “Stigma, Mental Health, and Resilience in an Online Sample of the US Transgender Population,” American Journal of Public Health 103, no. 5 (2013): 943–951. ↵

- For continuing discrimination, see C. Dorsen, “An Integrative Review of Nurse Attitudes towards Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Patients,” Canadian Journal of Nursing Research 44 (2012): 18–43; for lack of culturally inclusive LGBTQ+ communication and care, see K. L. Eckstrand and J. M. Ehrenfeld, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Healthcare: A Clinical Guide to Preventive, Primary, and Specialist Care (New York: Springer, 2016); M. J. Eliason and P. L. Chinn, LGBTQ Cultures: What Health Care Professionals Need to Know about Sexual and Gender Diversity, 3rd ed. (Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer, 2018); J. Landry, “Delivering Culturally Sensitive Care to LGBTQI Patients,” Journal for Nurse Practitioners 13, no. 5 (2017): 342–347; A. S. Keuroghlian, K. L. Ard, and H. J. Makadon, “Advancing Health Equity for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBTQ) People through Sexual Health Education and LGBTQ-Affirming Healthcare Environments,” Sexual Health 14 (2017): 119; F. A. Lim, D. V. Brown, and S. M. Kim, “Addressing Health Care Disparities in the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Population: A Review of Best Practices,” American Journal of Nursing 114 (2014): 24–34, https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000450423.89759.36; and Joint Commission, Advancing Effective Communication, Cultural Competence, and Family- and Patient-Centered Care for the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) Community: A Field Guide (Oak Brook, IL: Joint Commission, 2011); and for being invisible and experiencing discrimination, see R. Carabez, M. Pellegrini, A. Mankovitz, M. Eliason, M. Ciano, and M. Scott, “‘Never in All My Years . . .’: Nurses’ Education about LGBT Health,” Journal of Professional Nursing 31 (2015): 323–329; Eckstrand and Ehrenfeld, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Healthcare; and Eliason and Chinn, LGBTQ Cultures. ↵

- For the need for more education, see M. Eliason, S. Dibble, and J. De Joseph, “Nursing’s Silence on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Issues: The Need for Emancipatory Efforts,” Advances in Nursing Science 33 (2010): 206–218, https://doi.org/10.1097/ANS.0b013e3181e63e49; and F. Lim, M. Johnson, and M. J. Eliason, “A National Survey of Faculty Knowledge, Experience, and Readiness for Teaching Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health in Baccalaureate Nursing Programs,” Nursing Education Perspectives 36, no. 3 (2015): 144–152, https://doi.org/10.5480/14-1355; for the study of U.S. medical school hours on LGBTQ+ education, see J. Obedin-Maliver, E. S. Goldsmith, L. Stewart, W. White, E. Tran, S. Brenman, M. Wells, et al., “Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender-Related Content in Undergraduate Medical Education,” Journal of the American Medical Association 306 (2011): 971–977, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.1255; for other health provider education programs, see Lim, Johnson, and Eliason, “A National Survey of Faculty Knowledge”; and for lack of understanding of LGBTQ+ inclusive care, see Landry, “Delivering Culturally Sensitive Care to LGBTQI Patients.” ↵

- For the 2022 index, see Human Rights Campaign, “Healthcare Equality Index 2020,” https://www.hrc.org/resources/healthcare-equality-index. ↵

- For the provider directory, see GLMA, “For Patients,” accessed April 26, 2021, http://glma.org/index.cfm?fuseaction=Page.viewPage&pageId=939&grandparentID=534&parentID=938&nodeID=1; practitioners can see GLMA, “For Providers and Researchers,” accessed April 26, 2021, http://www.glma.org/index.cfm?fuseaction=Page.viewPage&pageId=940&grandparentID=534&parentID=534; and for the guidelines, see GLMA, Guidelines for Care of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Patients (San Francisco: GLMA, 2006), http://glma.org/_data/n_0001/resources/live/GLMA%20guidelines%202006%20FINAL.pdf. See also National LGBT Health Education Center, Ten Things: Creating Inclusive Health Care Environments for LGBT People (Boston, MA: Fenway Institute, 2016), https://www.lgbtqiahealtheducation.org/publication/ten-things/; and “LGBTQIA+ Glossary of terms for Health Care Teams,” published 3 February 2020, https://www.lgbtqiahealtheducation.org/publication/lgbtqia-glossary-of-terms-for-health-care-teams/”. ↵

- Institute of Medicine, The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People. ↵

- For health risks, including cancers, see Institute of Medicine, The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People; and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Health Considerations for LGBTQ Youth,” updated December 20, 2019, https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/disparities/smy.htm; for silicone use, see C. Bertin, R. Abbas, V. Andrieu, F. Michard, C. Rioux, V. Descamps, Y. Yazdanpanah, et al., “Illicit Massive Silicone Injections Always Induce Chronic and Definitive Silicone Blood Diffusion with Dermatologic Complications,” Medicine 98, no. 4 (2019), e14143. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000014143; and for prostate, anal, and colon cancer, see U. Boehmer, A. Ozonoff, and M. Xiaopeng, “An Ecological Analysis of Colorectal Cancer Incidence and Mortality: Differences by Sexual Orientation,” BMC Cancer 11 (2011): 400. ↵

- F. O. Buchting, L. Margolies, M. G. Bare, D. Bruessow, E. C. Díaz-Toro, C. Kamen, L. S. Ka‘opua, et al., “LGBT Best and Promising Practices throughout the Cancer Continuum,” 2016, https://moqc.org/wp-content/uploads/LGBT-HealthLink-Best-and-Promising-Practices-Throught-the-Cancer-Contiuum.pdf. ↵

Romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or sexual behavior toward both males and females or toward more than one sex or gender.

Biologically, an organism that has complete or partial reproductive organs and produces gametes normally associated with both male and female sexes.

People born with any of several variations in sex characteristics, including chromosomes, gonads, sex hormones, or genitals.

A concept in which individuals are categorized, either by themselves or by society, as neither man nor woman.

Behavior that deviates from the norm and that society considers immoral, inferior, pathological, and—in relation to evolutionary theory—a retreat from progress.

Pathogens that are commonly spread by sexual activity, especially vaginal intercourse, anal sex, and oral sex.

Also known as gender-affirming surgery; surgical procedures by which a transgender person’s physical appearance and function of their existing sexual characteristics are altered to resemble those socially associated with their identified gender.

Also known as sex reassignment surgery; surgical procedures by which a transgender person’s physical appearance and function of their existing sexual characteristics are altered to resemble those socially associated with their identified gender.

A sociological model, as proposed by Ilan Meyer, explaining why sexual minority individuals, on average, experience higher rates of mental health problems relative to their straight peers.

Overlapping or intersecting social identities, such as race, class, and gender, and related systems of oppression, domination, or discrimination.

The sexual, romantic, or emotional attraction toward people regardless of their sex or gender identity.

A measure of the probability of occurrence of a given medical condition in a population within a specified period of time.

The proportion of a particular population affected by a condition (typically a disease or a risk factor such as smoking or seat belt use).

The distress a person feels because of a mismatch between their gender identity and their sex assigned at birth.

A behavior or gender expression by an individual that does not match masculine or feminine gender norms.

The personal sense of one’s gender, which can correlate with assigned sex at birth or can differ from it.

A person’s behavior, mannerisms, interests, and appearance that are associated with gender in a particular cultural context, specifically with the categories of femininity or masculinity.

Hormone therapy in which sex hormones and other hormonal medications are administered to transgender or gender-nonconforming individuals to more closely align their secondary sexual characteristics with their gender identity.