Private: Part III: U.S. Histories

Chapter 5: LGBTQ+ Legal History

Dara J. Silberstein

Introduction

Historians often face the difficult task of determining how and when to tell the story of certain events, ideas, or people. This is no less true in telling the history of LGBTQ+ law in the United States. It may be surprising to many, but LGBTQ+ laws have a long, storied past and have existed as long as the United States itself. Laws enacted at local and state levels have long been used to regulate acceptable sex and gender norms. For example, in Arresting Dress, Clare Sears writes about the nineteenth-century San Francisco laws that outlawed cross-dressing.[1] These laws and resistance to them tell important stories about how LGBTQ+ practices were regulated. This chapter focuses on some of the key legal doctrines that have been crucial in determining the overall landscape of LGBTQ+ rights in the United States and the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the U.S. Constitution and its application to protecting members of LGBTQ+ communities.

Throughout this chapter it is important to remember that our system of constitutional law is premised on the rights enumerated in the federal constitution being natural rights—that is, rights that are inalienable and preexist our government. What this means is that the Bill of Rights, the first ten amendments to the Constitution, does not grant any rights. Rather, each amendment represents a mandate for the government to not interfere with individual rights or to not prevent others from doing so. For example, the First Amendment right to free speech does not mean that the government has to give you the means to speak, but it cannot interfere with your inalienable right to do so.[2] Crucial to any claim to protected rights is that one must be recognized as human. As anyone who is familiar with U.S. history knows, enslaved African and African Americans were deemed to be chattel (property) and not human, which served to deny them protections as enumerated by these rights. In addition, women, particularly married women, were not recognized as independent citizens and also lacked many of the Constitution’s enumerated rights. Though this egregious thinking would begin to be overturned in the latter half of the nineteenth century, keep it in mind as we survey the rights that eventually applied to members of the LGBTQ+ communities.

Ironically, sexuality, so basic to the human experience, was never mentioned in the original federal constitution or by James Madison, the principal architect of the Bill of Rights. This chapter provides an understanding of the constitutionally based issues that have influenced recent outcomes of the protected rights of LGBTQ+ communities. We begin with a closer look at the tenets that paved the way for recognition of sexual rights. Next we examine the process that eventually led the Supreme Court to extend these rights to include lesbian and gay sexualities. After that extension, the next large hurdle confronting the Court was the question of marriage equality. Finally, we briefly consider recent issues before the Court that go beyond sexual rights but strike at core understandings of LGBTQ+ equality.

Sexual Rights and the Constitution

The U.S. Constitution approved by the delegates to the 1787 Constitutional Convention did not include the protection of rights that were enumerated in the ten constitutional amendments, known as the Bill of Rights, that were eventually ratified in 1791. These amendments included guarantees such as the right to free speech, the right to due process, and the right to a speedy trial.[3] What was not enumerated or made explicit was a right to sexual liberty. How, then, would “we the people” come to expect the Constitution to protect such rights, particularly with respect to same-sex sexualities? An answer to this question begins with the Ninth Amendment’s statement that “the enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.” The inclusion of this amendment makes clear that the rights explicitly stated were not exclusive of those that were unenumerated and those that could not be anticipated. As the authors of Sexual Rights in America write, “As the guardian of fundamental rights unanticipated or underappreciated two centuries past, the Ninth Amendment transforms the Constitution from a static record of our forebears’ political and moral understandings into a dynamic and evolving expression of our basic rights.”[4] To be clear, the Ninth Amendment was not intended to protect the rights of all. As noted earlier, rights were explicitly denied to the enslaved Africans and African Americans who were considered to be not human but chattel, “the name given to things which in law are deemed personal property.”[5] Nor was the full range of rights available to women, particularly married women, who essentially merged their individuality into that of their husbands under the law of coverture. This meant that women were not only denied the vote but, when married, could not sign contracts or conduct other business independent from their husbands.[6]

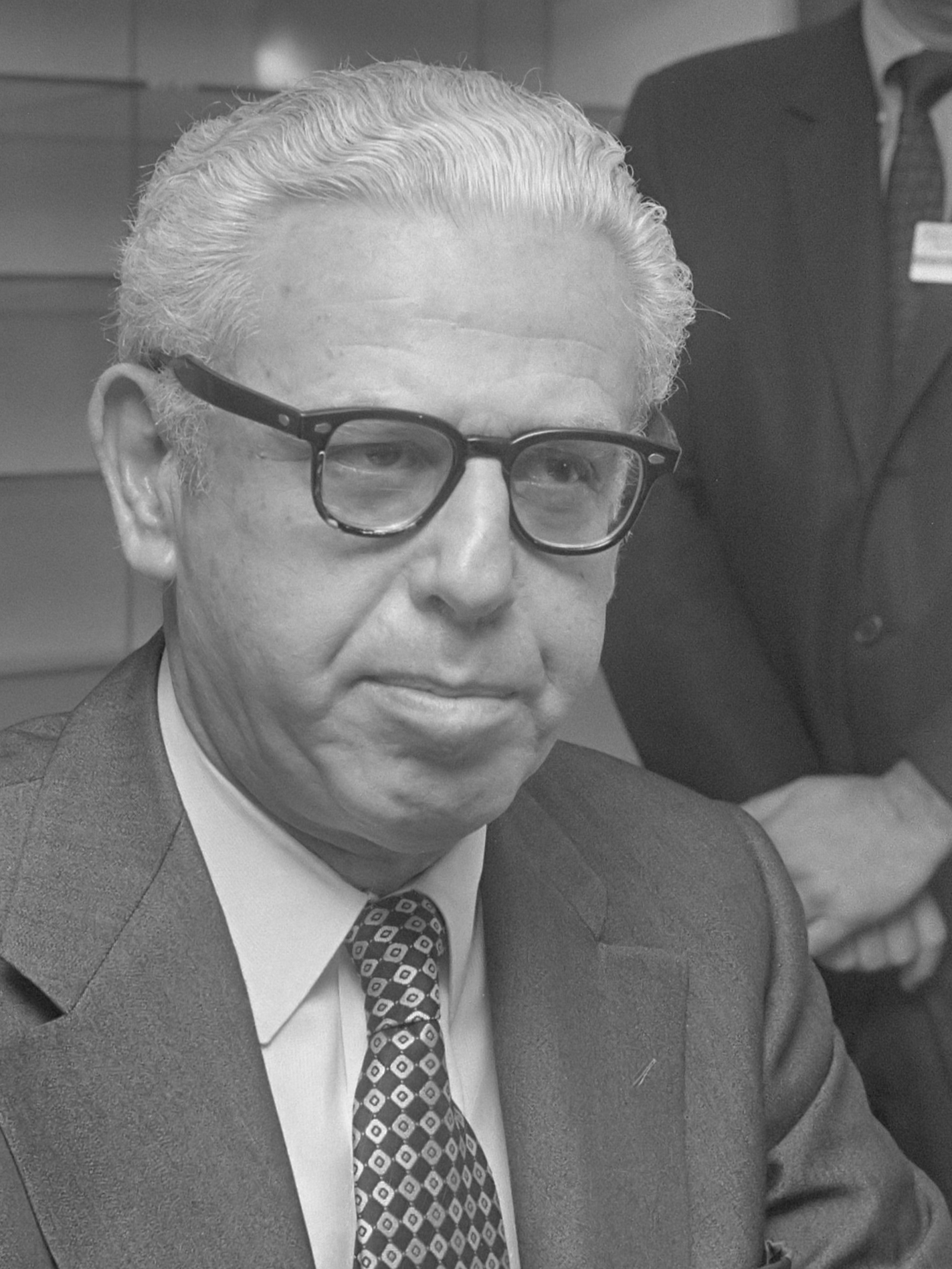

Nevertheless, the inclusion of the Ninth Amendment in the Bill of Rights provides a basis for protecting those rights considered to be natural and thus fundamental to liberty. As some have argued, this includes basic sexual rights, although the range and extent of these rights remains a source of great division among legal scholars and advocates.[7] This was precisely the point made by Justice Arthur Goldberg (figure 5.1) in his concurring opinion in Griswold v. Connecticut (1965), in which the Supreme Court found that a married couple had the fundamental right to privacy within marriage.[8] Arguing that the Ninth Amendment provided a constitutional basis for recognizing this fundamental right, Goldberg stated,

To hold that a right so basic and fundamental and so deep-rooted in our society as the right of privacy in marriage may be infringed because that right is not guaranteed in so many words by the first eight amendments to the Constitution is to ignore the Ninth Amendment, and to give it no effect whatsoever.[9]

Despite what might appear to be an easy way to expand on the rights protected by the Ninth Amendment, the court has rarely addressed its meaning or expanded the list of unenumerated rights it might imply.

The amendment that would provide the basis for sexual rights was the Fourteenth Amendment, one of the three amendments ratified in the post–Civil War period, which states in part,

No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.[10]

One interesting point to consider is that this amendment was ratified in response to the scourge of slavery’s system of racism. Under the Fourteenth Amendment, states could no longer deny some of its residents, particularly formerly enslaved people, their rights protected by the federal constitution. The least influential clause, the privileges and immunities clause, was significantly limited in scope by the Supreme Court in the Slaughter-House Cases (1873).[11] However, the equal protection and due process clauses have played significant roles in the development of sexual rights.

The Fourteenth Amendment’s due process clause does not specify what liberties it is meant to protect. The Court answered this question in Palko v. Connecticut (1937).[12] Writing for the Supreme Court, Justice Benjamin Cardozo found that this clause protected only those liberties that were “of the very essence of a scheme of ordered liberty.”[13] As a result of this decision, the liberties protected by the Bill of Rights were gradually applied to the states as well.

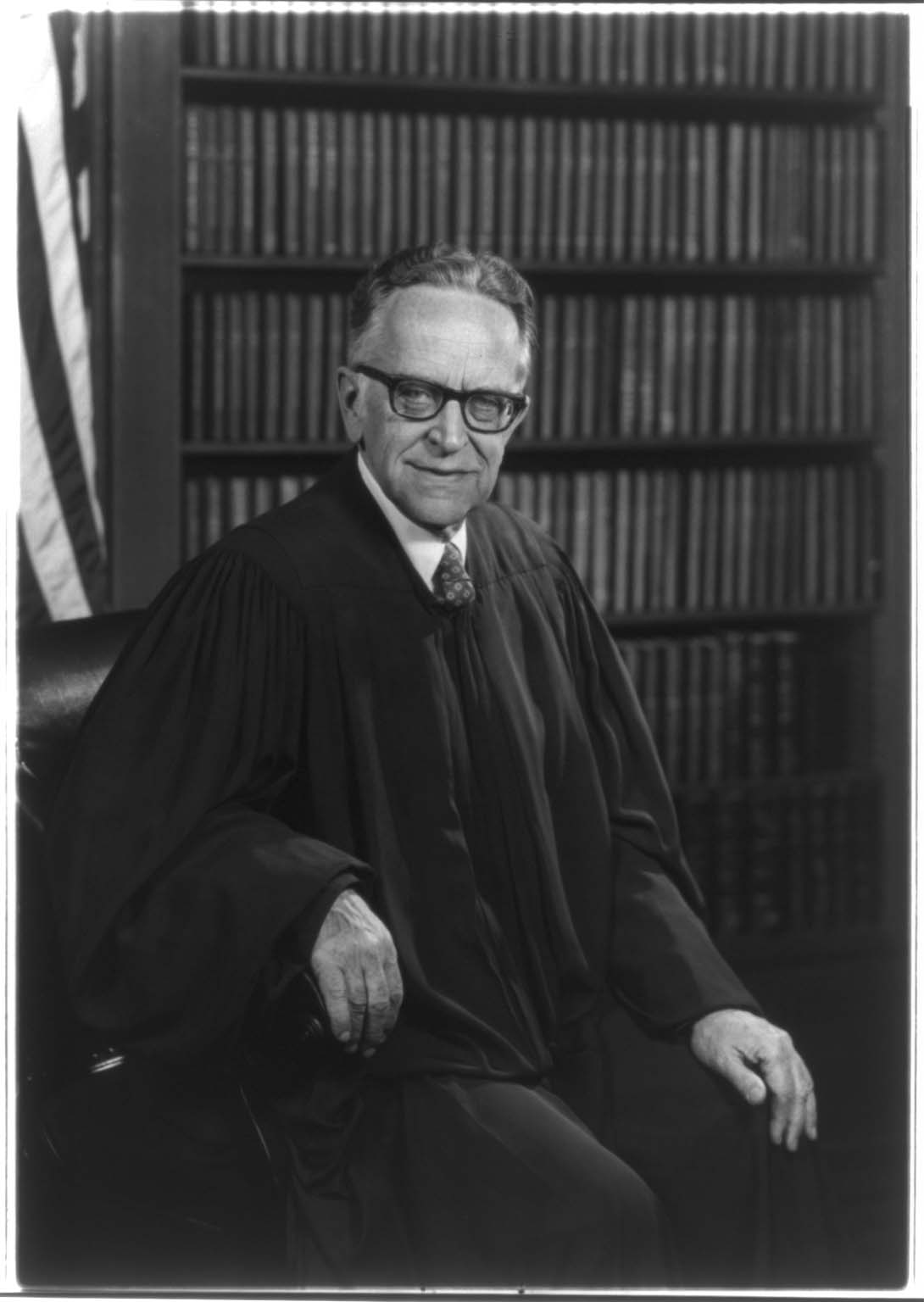

The Griswold case, in which the Supreme Court was asked to rule on whether a married couple had a right to birth control, took the Palko decision further and looked at whether such a right emanated from those enumerated within the Bill of Rights. In his Griswold majority opinion, Justice William Douglas wrote that “specific guarantees in the Bill of Rights have penumbras, formed by emanations from those guarantees that help give them life and substance.” He noted that a number of these guarantees create “zones of privacy” that suggest the framers certainly understood the existence of a fundamental right to privacy. Once this fundamental right was recognized, Douglas aptly applied it to intimate decisions between married couples.[14] As is well known, this fundamental right to privacy became the basis for Justice Harry Blackmun’s (figure 5.2) majority opinion in Roe v. Wade (1973), which found that Texas did not have enough of an interest in interfering with a woman’s fundamental right to privacy in choosing whether to have an abortion during the first trimester.[15] The trimester-based right to privacy was altered by the court’s subsequent decision in Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992), so that the question of the state’s interest in preventing women from exercising their fundamental right to privacy came to be measured against fetal viability: the more viable, the more the state had an interest in protecting the fetus.[16] Some have suggested that the Casey decision limited the fundamental quality of women’s right to privacy and is indicative of the Court’s willingness to limit the liberties protected under this Fourteenth Amendment right. Nevertheless, the Supreme Court’s decisions in the reproductive rights cases created the legal doctrine of the fundamental right to privacy that would eventually become useful in expanding the sexual rights extended to lesbian, gays, and bisexuals.

The Supreme Court first considered whether the right to privacy applied to same-sex sexuality in Bowers v. Hardwick.[17] In this decision, made in 1986 as the AIDS epidemic was ravaging members of LGBTQ+ communities, the Supreme Court demonstrated that it was unwilling to extend the fundamental right to privacy protections to gay men. The Bowers case arose from a challenge to Georgia’s laws criminalizing sodomy. A remarkable fact in Bowers was that the acts in question occurred in the privacy of Michael Hardwick’s bedroom. An Atlanta police officer went to serve what turned out to be an invalid arrest warrant on Hardwick for his failure to appear in court on a citation for alleged public drinking. Hardwick’s roommate allowed the officer to enter, whereupon he opened the bedroom door to find Hardwick and another man having sex. The officer arrested both men, charging them with homosexual sodomy, a felony under Georgia law.[18] From a legal advocacy perspective, this made the fact pattern in Bowers ideal to challenge Georgia’s sodomy law under the fundamental right to privacy. However, writing for the court, Justice Byron White did not find constitutional protection for homosexual sodomy. White noted the court’s previous review of fundamental rights surrounding heterosexual reproductive rights and found that homosexual sodomy was not “implicit in the concept of ordered liberty,” such that “neither liberty nor justice would exist if they were sacrificed.” He also dismissed the idea that the right to engage in homosexual sodomy was “deeply rooted in this Nation’s history and tradition.”[19] This idea, that somehow homosexuality was not a part of U.S. history, inspired historians to produce a range of scholarship that would become instrumental in the Court’s decision to overturn Bowers.

It took the Court seventeen years to overturn its Bowers decision, during which several states continued to criminalize same-sex sexuality. It is notable, however, that in terms of the history of overturned precedents this period was brief. For instance, the court’s seminal Brown v. Board of Education decision, ending race-based segregation in education, was issued nearly sixty years after the separate-but-equal doctrine was set forth in Plessy v. Ferguson, allowing states to impose legally sanctioned racial segregation.[20] The Bowers decision, however, held sway in the midst of the AIDS crisis and fostered an environment in which untold numbers of gay men would forgo early medical intervention in addressing the virus for fear of facing criminal charges.[21]

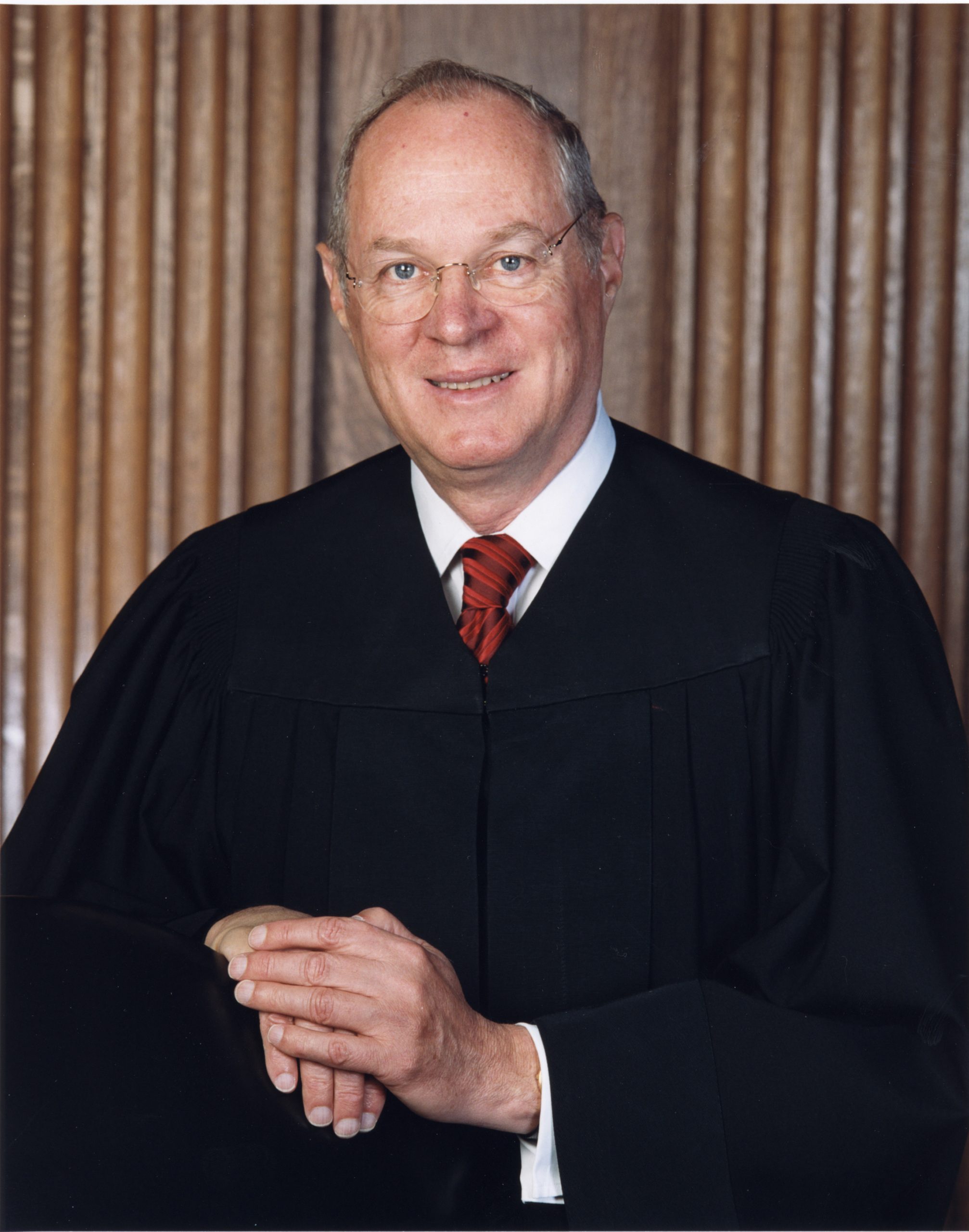

By 2003 the cultural landscape had shifted enough for the court to reconsider the question of the fundamental right to privacy protections afforded to homosexual sex in the case of Lawrence v. Texas (2003).[22] Writing for the majority, Justice Anthony Kennedy (figure 5.3) noted that the facts in Lawrence were similar to Bowers in that Lawrence and Garner were arrested for committing sodomy in the privacy of John Lawrence’s home when a police officer entered in response to a call about a weapons disturbance.[23] The law in Texas criminalized homosexual but not heterosexual sodomy. While advocates offered equal protection arguments in addition to the Fourteenth’s due process protection of the fundamental right to privacy, Justice Kennedy wrote that the case “should be resolved by determining whether the petitioners were free as adults to engage in the private conduct in the exercise of their liberty under the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution.”[24] Kennedy wrote that the sodomy laws sought to control behavior that was within

the liberty of persons to choose without being punished as criminals. . . . It suffices for us to acknowledge that adults may choose to enter upon this relationship in the confines of their homes and their own private lives and still retain their dignity as free persons. When sexuality finds overt expression in intimate conduct with another person, the conduct can be but one element in a personal bond that is more enduring. The liberty protected by the Constitution allows homosexual persons the right to make this choice.[25]

Kennedy’s opinion specifically challenged the historical framework previously set forth in Bowers and, in so doing, established the rootedness of homosexual intimacy as a liberty protected by the fundamental right to privacy. It is noteworthy that Kennedy did not embrace the equal protection clause in his decision, noting that “were we to hold the statute invalid under the Equal Protection Clause some might question whether a prohibition would be valid if drawn differently, say, to prohibit the conduct both between same-sex and different-sex participants.”[26] Kennedy did acknowledge that decriminalizing homosexual sodomy would lead to destigmatizing homosexuality itself, removing an unequal burden previously placed on homosexuals for their sexual intimacies.

One cannot overstate the impact of the Lawrence decision on the lives of LGB people whose intimate practices finally had protection as a fundamental liberty. That being said, some question the dependency of this liberty on a fundamental right to privacy because this emphasis on private sexual activities runs counter to practices within homosexual communities.[27] They suggest that for gay men cruising and sex in public spaces has been an important, integral part of their identities. Within this context, the private sex that the fundamental right is based on is viewed as assimilationist because it continues to marginalize homosexuals or even outright erase components of their sexualities.[28]

Marriage Equality

Having achieved the decriminalization of homosexuality in Lawrence, the question of the legal status of same-sex marriage became a focus of LGBTQ+ activism. This was due, in part, to the increase in anti-LGBTQ+ sentiment that resulted from the notion that the Lawrence decision had gone too far in normalizing homosexuality. Justice Antonin Scalia iterated this concern when he noted that after the court’s ruling, limiting marriage to heterosexuals was on “pretty shaky grounds.”[29] The focus on marriage equality was also due to LGB couples being denied basic protections during the AIDS epidemic, ranging from partners being denied input into medical decision-making to the eviction of surviving partners from their apartments.[30]

As advocates conducted a state-by-state effort to gain marriage equality, Hawaii became the first state in which its court ruled on the issue. In the 1996 case of Baehr v. Miike (originally known as Baehr v. Lewin when it was brought to court in 1993), the Hawaii Supreme Court ruled that same-sex marriage was legal given the state constitution’s equal rights amendment.[31] However, the impact of this decision was curtailed by the state legislature in 1998 when, after a statewide referendum, it amended the state constitution to define marriage to be legal only for opposite-sex couples. This constitutional change reflected the federal Defense of Marriage Act of 1996 (DOMA), which defined marriage as a “legal union between one man and one woman as husband and wife, and the word ‘spouse’ refers only to a person of the opposite sex who is a husband or a wife.”[32] During the ensuing period, several states took up the question of whether state laws would allow or ban same-sex marriage. In 2004 Massachusetts became the first state to legalize same-sex marriage. By the time the U.S. Supreme Court addressed the question of same-sex marriage in United States v. Windsor, thirty-seven states had legalized same-sex marriage.[33]

Same-sex marriage was not wholly embraced within LGBTQ+ communities. Some, like the LGBTQ+ attorney Paula Ettelbrick, argued that marriage was a patriarchal institution that would not liberate lesbians and gay men but would “force our assimilation into the mainstream and undermine the goals of gay liberation.”[34] Others maintained that same-sex marriage was misdirecting the LGBTQ+ movement’s attention away from more important efforts, including the kind of legal reform that would overturn laws targeting LGBTQ+ people.[35] Despite these objections, the main LGBTQ+ advocacy groups focused the bulk of their efforts on achieving marriage equality for same-sex couples.

The widespread disagreement between state laws and DOMA finally led the Supreme Court to address same-sex marriage in Windsor in 2013. That case involved the surviving partner of a same-sex marriage, Edith Windsor, who sought a refund from the Internal Revenue Service for taxes she was forced to pay on the estate of her spouse, Thea Spyer. Normally, spouses were exempt from paying taxes on their partner’s estate, but the IRS determined that irrespective of whether Windsor’s marriage was legal under New York state law, DOMA meant that it was not legal under federal law. Writing for the majority, Justice Kennedy concluded that DOMA’s “principal effect is to identify a subset of state-sanctioned marriages and make them unequal.” He therefore declared DOMA as a violation of equal protection.[36]

Windsor was a significant victory for same-sex marriage proponents because it declared DOMA unconstitutional. However, the question of whether states were allowed to prohibit same-sex marriages within their jurisdictions would not be resolved until 2015, two years after the Windsor decision, in the case of Obergefell v. Hodges (figure 5.5). Again writing for the majority, Justice Kennedy found that there was no justification for making a distinction between same-sex and opposite-sex marriages: “The limitation of marriage to opposite-sex couples may long have seemed natural and just, but its inconsistency with the central meaning of the fundamental right to marry is now manifest.”[37] Kennedy looked at the fundamental nature of marriage itself and determined that four guiding principles warranted constitutional protection for same-sex couples. First, he noted that the Court consistently found that the personal decision to marry was inherent to the idea of individual liberty. Second, Kennedy acknowledged that the Court had previously determined marriage to be a union unlike any other and that went to the heart of individual liberty. Third, he found that “by giving recognition and legal structure to their parents’ relationship, marriage allows children ‘to understand the integrity and closeness of their own family and its concord with other families in their community and in their daily lives.’” Fourth, Kennedy stated that “this Court’s cases and the Nation’s traditions make clear that marriage is a keystone of our social order.”[38]

Through this analysis Kennedy found that the fundamental right for same-sex couples to marry was protected by the Fourteenth Amendment’s due process clause. He went further to note that there was a synergy between this clause and the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause. He wrote, “The Due Process Clause and the Equal Protection Clause are connected in a profound way, though they set forth independent principles. . . . In any particular case one Clause may be thought to capture the essence of the right in a more accurate and comprehensive way, even as the two Clauses may converge in the identification and definition of the right.”[39] The legal scholar Lawrence Tribe has argued that, by linking equal protection to due process, Kennedy gives centrality and meaning to the legal doctrine of “equal dignity.”[40] Tribe suggests that equal dignity means all individuals deserve personal autonomy and freedom to define their own identity or existence. However, Kennedy’s focus on the tradition and sanctity of marriage in our social order enveloped the issue of LGBTQ+ rights under the cover of conservative notions of family values.[41] Certainly, intimacy plays a significant role in the way many LGBTQ+ people live their lives, but as others have suggested, this alone is not the sole basis for what it means to be queer.

LGBTQ+ and Equality

Before its Obergefell decision, the Supreme Court confronted the question of whether the equal protection clause protected against discrimination toward LGBTQ+ people. In 1996 the Court heard the case of Romer v. Evans, in which it was faced with the decision of whether Colorado’s Amendment 2 violated the equal protection clause. Amendment 2 was adopted in response to several municipal laws that banned discrimination in housing, employment, education, and public accommodation against LGBTQ+ people. The amendment prohibited any law designed to protect the status of people on the basis of their “homosexual, lesbian or bisexual orientation, conduct, practices or relationships.”[42] The state essentially argued that Amendment 2 did nothing more than put LGBTQ+ people on the same footing as all other Colorado residents who weren’t afforded the specific protections of the various laws within the state. However, in a decision authored by Justice Kennedy, the Court found that Amendment 2 violated the equal protection clause and was unconstitutional. Kennedy explained,

The Fourteenth Amendment’s promise that no person shall be denied the equal protection of the laws must co exist [sic] with the practical necessity that most legislation classifies for one purpose or another, with resulting disadvantage to various groups or persons. . . . We have attempted to reconcile the principle with the reality by stating that, if a law neither burdens a fundamental right nor targets a suspect class, we will uphold the legislative classification so long as it bears a rational relation to some legitimate end. . . . Amendment 2 fails, indeed defies, even this conventional inquiry.[43]

Kennedy found that Amendment 2’s exclusion of LGBTQ+ people from receiving legal protections already afforded to others failed to have a rational relationship to a legitimate governmental purpose, and as a result, it violated the minimal standard of review for equal protection cases.[44] This outcome was significant, especially coming after the Bowers decision, but it did not offer the kind of more rigid review given to laws that discriminate on the basis of race or gender. Some suggest that Kennedy’s use of the rational basis test meant that laws targeting LGBTQ+ people for unequal treatment might survive because legislation that could be rationalized would not violate the equal protection clause.[45] For instance, in the case of Boy Scouts of America v. Dale (2000) the court found that the Boy Scouts of America could revoke the adult membership of James Dale, who was a former Eagle Scout and assistant scoutmaster at the time of his ouster. The Boy Scouts claimed that their freedom of expressive association rights would be violated if forced to include Dale, who was a known homosexual and gay rights activist. Writing for the majority, Chief Justice William Rehnquist found,

We are not, as we must not be, guided by our views of whether the Boy Scouts’ teachings with respect to homosexual conduct are right or wrong; public or judicial disapproval of a tenet of an organization’s expression does not justify the State’s effort to compel the organization to accept members where such acceptance would derogate from the organization’s expressive message.[46]

Rehnquist’s opinion read much more into the “expressive” association than was evidenced by the Boy Scouts’ mission, oath, and handbook. Indeed, none of the written records Rehnquist relied on explicitly mentioned how the values the organization purportedly espoused were directly challenged by the inclusion of Dale. This case has not been overturned, although the Boy Scouts themselves have, in recent years, opened their doors to gay men and lesbians.

If a heightened review of LGBTQ+ equal protection had been implemented in the case of Masterpiece Cakeshop, Ltd. v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission (2018), that might have influenced its outcome. In that case the Court was faced with the question of whether a Colorado baker’s religious freedom protected his right to not make a wedding cake for a same-sex wedding (figure 5.6). The couple in this case brought a complaint to Colorado’s Civil Rights Commission, which found in their favor, citing the state’s antidiscrimination law. Justice Kennedy wrote for the court, “While it is unexceptional that Colorado law can protect gay persons in acquiring products and services on the same terms and conditions as are offered to other members of the public, the law must be applied in a manner that is neutral toward religion.”[47] However, this case was narrowly decided in that the Court’s ruling was not so much about religious freedom as it was about the obvious hostility toward the baker’s religious beliefs as expressed by the state’s civil rights commission. In this way the Court left open the door of whether religious freedom protections outweigh the right for LGBTQ+ people to live free from discrimination. As the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund amicus brief argued, allowing religious beliefs to serve as a basis for discrimination puts in jeopardy groups like African Americans who historically endured discrimination because of the religious beliefs held by some that whites were naturally superior to nonwhites.[48] Applying heightened scrutiny to laws and acts that discriminate against LGBTQ+ people might tip the balance of such cases in favor of equal protection over religious freedom in the future.

The previous cases look at issues related to the Constitution’s protection against sexuality discrimination. The Court decided in 2020 that legal protections extend to those who are gender nonconforming. In Bostock v. Clayton County, Georgia, the Court held that gay and gender-nonconforming people are protected by Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, which bars employers from discriminating against employees on the basis of sex, race, national origin, and religion.[49]

Indeed, the United States has a long history of discriminating against gender-nonconforming people. Several cities, including San Francisco and New York, had laws that criminalized those who wore clothing not deemed appropriate to their sex.[50] Today, discrimination against gender-nonconforming people is fairly common. New York allows individuals to change their gender on their driver’s licenses and other official documents, but few other states do. As is often discussed, the grouping of gender-nonconforming people under the LGBTQ+ umbrella has often meant specific gender-based issues are overshadowed by those that are sexuality based. Nevertheless, in the case of Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins (1989), the Court determined that sex stereotyping was a form of prohibited sex discrimination, which might open the door for greater protections for those who are gender nonconforming. In that case, Ann Hopkins was denied partnership in an accounting firm because several of the review partners found that she was not feminine enough. The Court found that this was a form of sex stereotyping, which it defined as “a person’s nonconformity to social or other expectations of that person’s gender.”[51] In its conclusion the Court found that the sex-based actions would be permissible if the employer could prove that Hopkins would not have been promoted in any event, but it was unable to do so in the subsequent court hearings. Though this precedent provides some hope to those advocating on behalf of LGBTQ+ people, it remains to be seen whether the Court will go so far as to afford protections against workplace discrimination in a way that expands the current scope of its previous decisions and current federal laws.

Profile: Anti-LGBTQ+ Hate Crimes in the United States: Histories and Debates

Ariella Rotramel

On June 12, 2016, forty-nine people were killed and fifty-three wounded in the Pulse nightclub shooting in Orlando, Florida. It was the deadliest single-person mass shooting and the largest documented anti-LGBTQ+ attack in U.S. history. Attacking a gay nightclub on Latin night resulted in over 90 percent of the victims being Latinx and the majority being LGBTQ+ identified. This act focused on an iconic public space that provided LGBTQ+ adults an opportunity to explore and claim their sexual and gender identities. The violence at Pulse echoed the 1973 UpStairs Lounge arson attack in New Orleans that killed thirty-two people. These mass killings are part of a broader picture of violence that LGBTQ+ people experience, from the disproportionate killings of transgender women of color to domestic violence and bullying in schools. There are different perspectives within the LGBTQ+ community about responses to hate-motivated violence. These debates concern whether the use of punitive measures through the criminal legal system supports or harms the LGBTQ+ community and whether more radical approaches are needed to address the root causes of anti-LGBTQ+ violence. This profile explores hate crimes as both a legal category and a broader social phenomenon.

What Are Hate Crimes?

Anti-LGBTQ+ hate crimes have had a simultaneously spectacular and invisible role in U.S. society. Today, hate crimes are defined as criminal acts motivated by bias toward victims’ real or perceived identity groups.[52] Hate crimes are informal social control mechanisms used in stratified societies as part of what Barbara Perry calls a “contemporary arsenal of oppression” for policing identity boundaries.[53] Hate crimes occur within social dynamics of oppression, in which othered groups are vulnerable to systemic violence, pushing marginalized groups further into the political and social edges of society. It is theorized that hate crimes are driven by conflicts over cultural, political, and economic resources; bias and hostility toward relatively powerless groups; and the failure of authorities to address hate in society.[54]

Since the colonial period, violence against members of the LGBTQ+ community has been documented in the Western Hemisphere. Colonists drew on an interpretation of Judeo-Christian theology that viewed nonprocreative sex and gender nonconformity as sinful. Thus, violence toward people who did not conform to the colonists’ gender and sexual norms, along with social exclusion, was viewed as permissible.[55]

With the advent of sexual identities such as the “homosexual” in the late 1800s, anti-sodomy and related laws became increasingly used to target LGBTQ+ people in North America and Europe during the twentieth century. These same laws were also imposed on indigenous peoples throughout the world as a result of colonialism. Yet incidents such as the 1960s Compton’s Cafeteria riot and Stonewall rebellion demonstrated that LGBTQ+ people, particularly trans women of color, were no longer willing to tolerate police harassment that resulted in arrests and violence because of who they were (figure 5.7).[56] As the modern LGBTQ+ rights movement emerged, activists challenged the idea that they deserved to be targeted for violence because of their identities. Despite the long history of bias-based crimes, it took centuries for this to become understood and labeled as hate crimes.[57]

Prejudicial cultural norms perpetuate otherness, promoting prejudice and normalizing and rewarding hate, as well as punishing those who respect and embrace difference.[58] Cultures of hate identify marginalized groups as enemies through dehumanization and perpetuate group violence.[59] Perpetrators’ actions thus reflect an understanding and navigation of overarching social structures that separate the othered from the accepted. In the case of anti-LGBTQ+ hate crimes, heterosexism is an oppressive ideology that rejects, degrades, and others “any non-heterosexual form of behavior, identity, relationship or community.” It provides a complementary bias to cissexism, the oppressive ideology that denigrates transgender, gender nonbinary, genderqueer, and gender-nonconforming people.[60] Anti-LGBTQ+ hate crimes are based in a view of the LGBTQ+ community as a suitable target for violence.[61] Such crimes are often identified as hate based by such factors as that “the perpetrator [was] making homophobic comments; that the incident had occurred in or near a gay-identified venue; that the victim had a ‘hunch’ that the incident was homophobic; that the victim was holding hands with their same-sex partner in public, or other contextual clues.”[62] Importantly, anti-LGBTQ+ hate crimes intersect with hate crimes against gender, racial and ethnic, and other marginalized people.[63]

State-enacted or state-sanctioned violence against LGBTQ+ people has not been deemed a form of hate crime, though it draws on hatred toward a group of people. The hate-crime framework has focused largely on the acts of private individuals rather than addressing larger institutionalized forms of hate-motivated violence such as forced conversion therapy or abuse within the criminal and military systems. One estimate attributes almost one-quarter of hate crimes to police officers.[64] Anti-LGBTQ+ violence committed by police officers undermines LGBTQ+ victims’ willingness to report crimes, particularly after experiencing police violence firsthand or having communal knowledge that police officers may not view LGBTQ+ victims as deserving of appropriate services. Even when victims are willing to take the risk of reporting a hate crime, they can be unsuccessful. For example, despite a Minnesota state law requiring police to note in initial reports any victims’ belief that they have experienced a bias-motivated incident, responding officers fulfilled less than half of hate-crime filing requests between 1996 and 2000.[65] Because of bias, lack of training, and limited application, significant underreporting of sexual orientation and gender-motivated hate crimes at the state and federal levels occurs.

Criminalizing Hate

The Enforcement Act of 1871, also known as the Ku Klux Klan Act, addressed rampant anti-Black violence and marked the first effort at the federal level to criminalize hate crimes.[66] However, the Supreme Court’s United States v. Harris decision in 1883 greatly weakened the act and the ability of the federal government to intervene when states refused to prosecute hate crimes.[67] In the wake of the mid-twentieth-century civil rights movement and violence against activists, the 1968 Civil Rights Law covering federally protected activities was signed into law. It gave federal authorities the power to investigate and prosecute crimes motivated by actual or perceived race, color, religion, or national origin while a victim was engaged in a federally protected activity—for example, voting, accessing a public accommodation such as a hotel or restaurant, or attending school. The categories of identity named by the law were the key social categories of concern during this period and followed the language of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. However, the law excluded sex, reflecting an unwillingness to address gender-based discrimination fully rather than piecemeal through laws such as Title IX of the Education Amendments Act of 1972.

In 1978, California enacted the first state law enhancing penalties for murders based on prejudice against the protected statuses of race, religion, color, and national origin. State lawmakers took the lead in developing explicit hate-crime laws, and federal legislators followed suit in the mid-1980s.[68] The emergent LGBTQ+ movement gained traction in the 1980s as the HIV/AIDS epidemic, its toll on the community, and intolerance toward its victims galvanized activists. For example, New York’s Anti-Violence Project (AVP) was founded in 1980 to respond to violent attacks against gay men in the Chelsea neighborhood. A major concern for these groups was the lack of documentation of such crimes; without evidence that these incidents were part of a broader picture of violence, it was difficult to push efforts to address hate crimes. As a lead member of the National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs, AVP has coordinated many hate-violence reports since the late 1990s.[69] Such groups also have pushed for governmental efforts to collect data and criminalize hate crimes.

In 1985, U.S. Representative John Conyers proposed the Hate Crime Statistics Act to ensure the federal collection and publishing annually of statistics on crimes motivated by racial, ethnic, or religious prejudice.[70] It took five years for the Hate Crimes Statistics Act to become law, in 1990, and it did so only after sexual orientation was explicitly excluded from the legislation. The text of the law emphasizes that nothing in the act (1) “creates a cause of action or a right to bring an action, including an action based on discrimination due to sexual orientation” and (2) “shall be construed, nor shall any funds appropriated to carry out the purpose of the Act be used, to promote or encourage homosexuality.”[71]

Congress took great pains to emphasize that the legislation did not prevent discrimination against LGBTQ+ people nor did it support that community. The law reinforces that Congress was not treating sexual orientation as it did other social identities that were already protected under civil rights laws. The law resulted in the Federal Bureau of Investigation collecting data from local and state authorities about hate crimes, but there are major challenges to collecting accurate data. Police are not consistently trained at the local and state levels to address anti-LGBTQ+ hate crimes, and there continues to be stigma and risk associated with identifying as LGBTQ+ to such authorities. Reporting practices thus vary dramatically across contexts, but the law has assisted antiviolence groups in gaining official data to document violence.

The 1998 beating and torture death of college student Matthew Shepard in Laramie, Wyoming, became a rallying point to address hate crimes more fully in the late 1990s. His murder received substantial media coverage and inspired political action as well as artistic works. As an affluent, white, gay young man, Shepard became a symbol of antigay violence. His attackers were accused of attacking him because of antigay bias but were not charged with committing a hate crime because Wyoming had no laws that covered anti-LGBTQ+ crimes. The attention to his death contrasted with the lesser attention given to Brandon Teena’s sexual assault and murder, which was immortalized in the film Boys Don’t Cry (1999), and to the untold number of murders of trans women, particularly women of color.[72]

Although the particularities of the case have been debated, Shepard’s murder became iconic and served as a means of challenging U.S. lawmakers and society at large to address hate-motivated violence. The Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr., Hate Crimes Prevention Act was passed by the U.S. House of Representatives on October 8, 2009, and the U.S. Senate on October 22, 2009.[73] James Byrd Jr., a Black man, was attacked, chained to a truck, and dragged to his death for over two miles in Jasper, Texas. Both crimes received national attention, and there was public outrage that neither Texas nor Wyoming could enhance the punishment for these bias-motivated murders.[74] The act expanded protections to victims of bias crimes that were “motivated by the actual or perceived gender, disability, sexual orientation, or gender identity of any person,” becoming the first federal criminal prosecution statute addressing sexual orientation and gender-identity-based hate crimes.[75] It also increased the punishment for hate-crime perpetrators and allows the Department of Justice to assist in investigations and prosecutions of these crimes. On October 28, 2009, in advance of signing the act into law, President Barack Obama stated, “We must stand against crimes that are meant not only to break bones, but to break spirits, not only to inflict harm, but to inflict fear.” His words emphasized the broader social context of hate crimes, experienced as attacks on marginalized communities.[76]

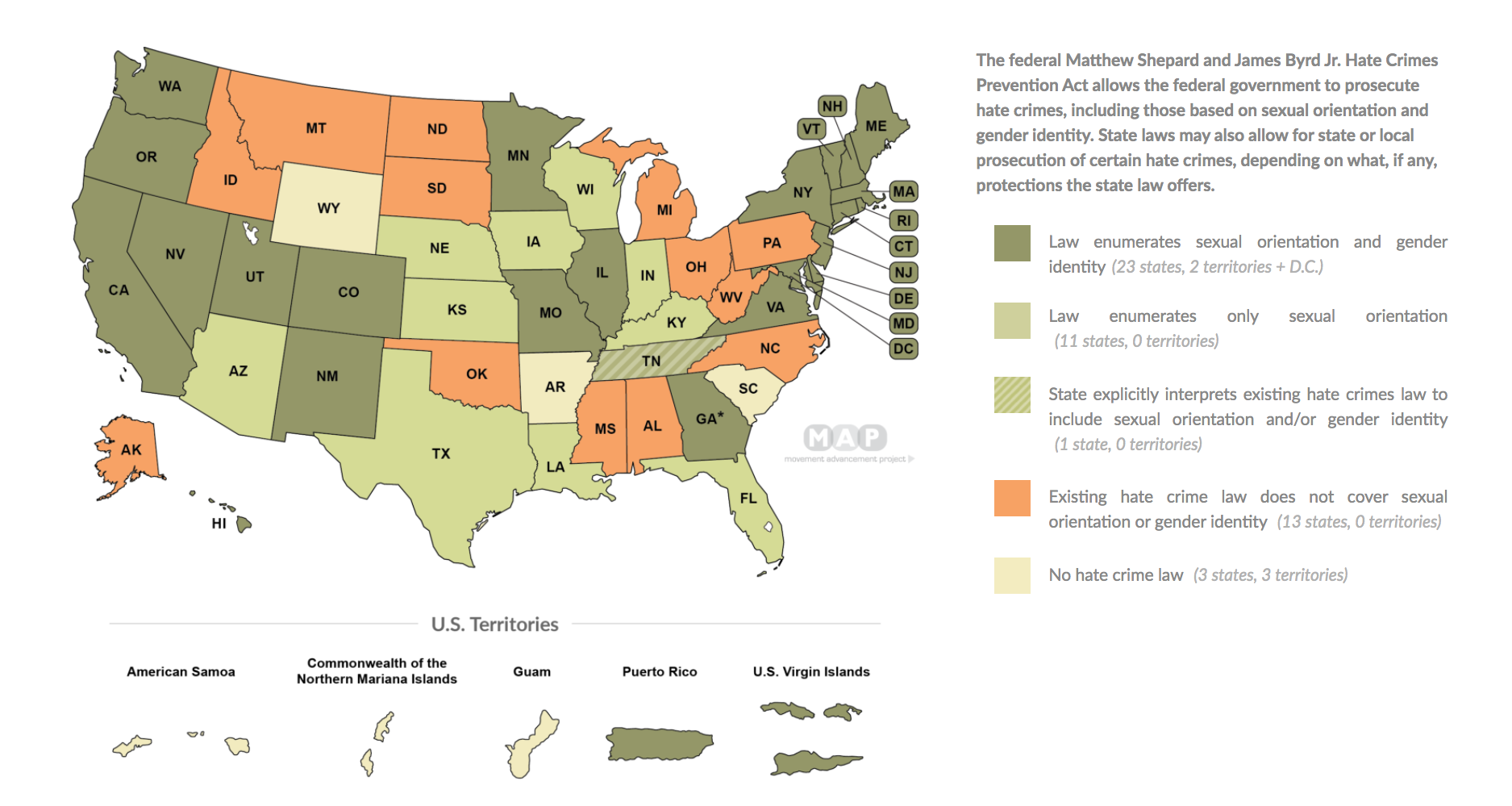

Federal laws address constitutional rights violations, but states have—or don’t have—their own specific hate-crime laws.[77] Today, there are a wide range of laws regarding hate-crime protections across states, and they vary regarding protected groups, criminal or civil approaches, crimes covered, complete or limited data collection, and law enforcement training.[78] As of 2019, nineteen states did not have any LGBT hate-crime laws, and twelve states had laws that covered sexual orientation but did not address gender identity and expression. Twenty states included both sexual orientation and gender identity in their hate-crime laws.[79] The majority of these laws were created in the first years of the 2000s, gender identity and expression were included in following years.

Debating Hate-Crime Laws

The arguments supporting hate-crime laws note that offenders’ acts promote the unequal treatment of not only individuals but also the broader communities that victims belong to, cause long-term psychological consequences for victims, and violate victims’ ability to freely express themselves.[80] The creation of laws serves to “form a consensus about the rights of stigmatized groups to be protected from hateful speech and physical violence.”[81] This approach, however, centers on the perpetrator perspective and avoids a structural approach to oppression that acknowledges the numerous forms of bias and the overarching perpetuation of bias in society. Many scholars have criticized the term hate crime for its erasure of the broader structures that support hate violence and instead placing the blame for such acts solely on individuals assumed to be pathological and acting out of emotion.[82] Moreover, hate-crime laws primarily function at the symbolic level; crimes are reported at low rates, and statutes are not applied to such crimes by authorities.[83] Such laws focus not on prevention of crimes but rather on punitive measures to punish particular crimes.

With the existing high incarceration rates of LGBTQ+ people as well as people of color, hate-crime laws support rather than challenge mass incarceration.[84] Some activists argue for efforts to “build community relationships and infrastructure to support the healing and transformation of people who have been impacted by interpersonal and intergenerational violence; [and efforts to] join with movements addressing root causes of queer and trans premature death, including police violence, imprisonment, poverty, immigration policies, and lack of healthcare and housing.”[85]

No universal consensus about the role of hate-crime laws in furthering the acceptance and inclusion of LGBTQ+ people in American society currently exists (figure 5.8). For many people such laws carry with them an emphasis on the value of their lives and help further their sense of belonging. Others, particularly LGBTQ+ activists engaged in broader social justice struggles, argue that such laws shore up a broken criminal justice system that is predicated on a violent logic that cannot truly benefit the LGBTQ+ community.

Media Attributions

- Figure 5.2. is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 5.8. © Courtesy of the Movement Advancement Project is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- C. Sears, Arresting Dress: Cross-Dressing, Law, and Fascination in Nineteenth-Century San Francisco (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015). ↵

- C. Mackinnon, Only Words (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1996). ↵

- U.S. Const. amends. I, V, and VI. ↵

- P. Abramson, S. D. Pinkerton, and M. Huppin, Sexual Rights in America: The Ninth Amendment and the Pursuit of Happiness (New York: New York University Press, 2003), 2. ↵

- The Law Dictionary, s.v. “What Is Chattel,” accessed March 14, 2022, https://thelawdictionary.org/chattel/. ↵

- The Law Dictionary, s.v. “What Is Coverture,” accessed March 14, 2022, https://thelawdictionary.org/coverture/. ↵

- Abramson, Pinkerton, and Huppin, Sexual Rights in America. ↵

- Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965). ↵

- Griswold, 381 U.S. at 492. ↵

- U.S. Const. amend. XVI. ↵

- Slaughter-House Cases, 83 U.S. 36 (1873). ↵

- Palko v. Connecticut, 302 U.S. 319, 325 (1937). ↵

- Palko, 302 U.S. at 325. ↵

- Griswold, 381 U.S. at 484, 486. ↵

- Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973). ↵

- Planned Parenthood v. Casey, 505 U.S. 833 (1992). ↵

- Bowers v. Hardwick, 478 U.S. 186 (1986). ↵

- W. N. Eskridge, Dishonorable Passions: Sodomy Laws in America, 1861–2003 (New York: Penguin, 2008), 232–234. ↵

- Bowers 478 U.S. at 192 (quoting) Palko 302 U.S. at 326. ↵

- Brown v. Board of Education 347 U.S. 483 (1954); Plessy v. Ferguson 163 U.S. 537 (1896); Bowers, 478 U.S. at 192 (quoting) Griswold, 381 U.S. at 506. ↵

- S. McGuigan, “The AIDS Dilemma: Public Health v. Criminal Law,” Law and Inequality: A Journal of Theory and Practice 4, no. 3 (1986): 545–577. ↵

- Several have advocated for the case being known as Lawrence and Garner v. Texas because Tyrone Garner was a copetitioner on the case and a man of color, and not including his name continues the practice of erasing people of color from history. M. Spindelman, “Tyrone Garner’s Lawrence v. Texas,” Michigan Law Review 111, no. 6 (2013), https://repository.law.umich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1074&context=mlr. ↵

- Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558 (2003). ↵

- Lawrence, 539 U.S. 564. ↵

- Lawrence, 539 U.S. 567. ↵

- Lawrence, 539 U.S. 575. ↵

- D. Bell, J. Binnie, R. Holiday, R. Longhurst, and R. Peace, Pleasure Zones: Bodies, Cities, Spaces (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2011). See also “Getting Rid of Sodomy Laws: History and Strategy That Led to the Lawrence Decision,” ACLU, accessed April 21, 2021, https://www.aclu.org/other/getting-rid-sodomy-laws-history-and-strategy-led-lawrence-decision. ↵

- J. E. Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (New York: New York University Press, 2009). ↵

- Lawrence, 539 U.S. 601. ↵

- J. D’Emilio, “Will the Courts Set Us Free? Reflections on the Campaign for Same-Sex Marriage,” in The Politics of Same-Sex Marriage, ed. C. Wilcox and C. A. Rimmerman (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007), 39–64. ↵

- Baehr v. Miike 910 P.2d 112 (1996); Baehr v. Lewin 74 Haw. 530, 852 P.2d 44 (1993). ↵

- Defense of Marriage Act, H.R. 3396, 104th Cong. (1996), § 3. ↵

- United States v. Windsor, 570 U.S. 744 (2013); W. N. Eskridge, “How Government Unintentionally Influences Culture (the Case of Same-Sex Marriage),” Northwestern University Law Review 102 (2008): 495–498. ↵

- P. Ettelbrick, “Since When Is Marriage a Path to Liberation?,” Out/Look: National Lesbian and Gay Quarterly 6 (1989): 14. ↵

- L. Duggan, “Beyond Marriage: Democracy, Equality, and Kinship for a New Century,” Scholar and Feminist Online 10, nos. 1–2 (Fall 2011–Spring 2012), https://sfonline.barnard.edu/a-new-queer-agenda/beyond-marriage-democracy-equality-and-kinship-for-a-new-century/. ↵

- Obergefell v. Hodges, 576 U.S. 644 at 646 (quoting) U.S. v. Windsor, 570 U.S. 744 at 759. ↵

- Obergefell, 576 U.S. at 659. ↵

- Obergefell, 576 U.S. at 672. ↵

- Obergefell, 576 U.S. at 681. ↵

- L. H. Tribe, “Equal Dignity: Speaking Its Name,” Harvard Law Review Forum 129 (2015): 16–32. ↵

- E. J. Baia, “Akin to Madmen: A Queer Critique of the Gay Rights Cases,” Virginia Law Review 104 (2018): 1021–1063. ↵

- Romer v. Evans, 517 U.S. 620 (1996). ↵

- Romer, 517 U.S. at 631–632. ↵

- Romer, 517 U.S. at 635. ↵

- J. B. Smith, “The Flaws of Rational Basis with Bite: Why the Supreme Court Should Acknowledge Its Application of Heightened Scrutiny to Classifications Based on Sexual Orientation,” Fordham Law Review 73 (2005): 2769–2814. ↵

- Boy Scouts of America v. Dale, 530 U.S. 640, 661 (2000). ↵

- Masterpiece Cakeshop, Ltd. v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission, 584 U.S. 2 (2018). ↵

- S. Ifill, “Symposium: The First Amendment Protects Speech and Religion, Not Discrimination in Public Spaces,” SCOTUSblog, June 5, 2018, https://www.scotusblog.com/2018/06/symposium-the-first-amendment-protects-speech-and-religion-not-discrimination-in-public-spaces/. ↵

- Bostock v. Clayton County, Georgia, No. 17-1618 (2020). ↵

- Sears, Arresting Dress ↵

- Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins, 490 U.S. 228, 251 (1989). ↵

- R. Blazak, “Isn’t Every Crime a Hate Crime? The Case for Hate Crime Laws,” Sociology Compass 5, no. 4 (2011): 245. ↵

- B. Perry, “The Sociology of Hate: Theoretical Approaches,” Hate Crimes, vol. 1, Understanding and Defining Hate Crime, ed. B. Perry et al. (Westport, CT: Greenwood, 2009), 56. ↵

- C. Turpin-Petrosino, “Historical Lessons: What’s Past May Be Prologue,” in Hate Crimes, vol. 2, ed. B. Perry et al. (Westport, CT: Greenwood, 2009), 34. ↵

- See chapter 3. ↵

- S. Levin, “Compton’s Cafeteria Riot: A Historic Act of Trans Resistance, Three Years before Stonewall,” Guardian, June 21, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2019/jun/21/stonewall-san-francisco-riot-tenderloin-neighborhood-trans-women; Meredith Worthen, “The Stonewall Inn: The People, Place and Lasting Significance of ‘Where Pride Began,’” in Biography, June 21, 2017; updated June 26, 2020, https://www.biography.com/news/stonewall-riots-history-leaders. ↵

- Turpin-Petrosino, “Historical Lessons.” ↵

- J. Levin and G. Rabrenovic, “Hate as Cultural Justification for Violence,” in Perry et al., Hate Crimes, 1:41–53; B. Perry, “Where Do We Go from Here? Researching Hate Crime,” Internet Journal of Criminology 3 (2003): 45–47. ↵

- Levin and Rabrenovic, “Hate as Cultural Justification for Violence”; Perry, “The Sociology of Hate.” ↵

- G. M. Herek, “The Social Context of Hate Crimes: Notes on Cultural Heterosexism,” in Hate Crimes: Confronting Violence against Lesbians and Gay Men, ed. Gregory M. Herek and Kevin T. Berrill (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 1992), 89. ↵

- Perry, “The Sociology of Hate”; H. J. Alden and K. F. Parker, “Gender Role Ideology, Homophobia and Hate Crime: Linking Attitudes to Macro-Level Anti-gay and Lesbian Hate Crimes,” Deviant Behavior 26 (2005): 321–343; D. P. Green, L. H. McFalls, and J. K. Smith, “Hate Crime: An Emergent Research Agenda,” Annual Review of Sociology 27, no. 1 (2001): 479–504; Herek, “The Social Context of Hate Crimes.” ↵

- N. Chakraborti and J. Garland, Hate Crime: Impact, Causes and Responses (London: Sage, 2009), 57–58. ↵

- E. Dunbar, “Race, Gender, and Sexual Orientation in Hate Crime Victimization: Identity Politics or Identity Risk?,” Violence and Victims 21, no. 3 (2006): 323–327. ↵

- K. T. Berrill, “Anti-gay Violence and Victimization in the United States: An Overview,” Journal of Interpersonal Violence 5, no. 3 (1990): 274–294. ↵

- K. B. Wolff and C. L. Cokely, “‘To Protect and to Serve?’: An Exploration of Police Conduct in Relation to the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Community,” Sexuality and Culture 11, no. 2 (2007): 15. ↵

- J. Lurie and S. P. Chase, The Chase Court: Justices, Rulings, and Legacy (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2004), 140. ↵

- United States v. Harris, 106 U.S. 629 (1883). ↵

- V. Jenness and R. Grattet, Making Hate a Crime: From Social Movement to Law Enforcement (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2001). ↵

- “Reports: Hate Violence Reports,” Anti-Violence Project, accessed December 29, 2021, https://avp.org/reports/. ↵

- Perry, “Where Do We Go from Here?”; Hate Crimes Statistics Act: Hearing before the Subcommittee on Criminal Justice of the Committee on the Judiciary, 99th Cong., 1st sess. (1985), https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/jmd/legacy/2013/09/06/hear-137-1985.pdf. ↵

- Hate Crime Statistics Act, H.R.1048, 101st Cong. (1989–1990), https://www.congress.gov/bill/101st-congress/house-bill/1048/text. ↵

- For an incomplete list of such murders, see Wikipedia, s.v. “List of People Killed for Being Transgender,” last modified April 18, 2021, 07:00, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_unlawfully_killed_transgender_people. ↵

- A. L. Bessel, “Preventing Hate Crimes Without Restricting Constitutionally Protected Speech: Evaluating the Impact of the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act on First Amendment Free Speech Rights,” Journal of Public Law and Policy 31 (2010): 735–775. ↵

- B. A. McPhail, “Hating Hate: Policy Implications of Hate Crime Legislation,” Social Service Review 74, no. 4 (2000): 635–653. ↵

- Department of Justice, “The Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr., Hate Crimes Prevention Act of 2009,” updated October 18, 2018, http://www.justice.gov/crt/about/crm/matthewshepard.php. ↵

- Office of the Press Secretary, White House, “Remarks by the President at Reception Commemorating the Enactment of the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act,” press release, October 28, 2009, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/remarks-president-reception-commemorating-enactment-matthew-shepard-and-james-byrd-. ↵

- J. Levin and J. McDevitt, Hate Crimes Revisited: American’s War against Those Who Are Different (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2002). ↵

- M. Shively, Study of Literature and Legislation on Hate Crime in America (Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice, 2005), ii, https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/210300.pdf. ↵

- Movement Advancement Project, “Equality Maps: Hate Crime Laws,” accessed April 22, 2021, https://www.lgbtmap.org/equality-maps/hate_crime_laws. ↵

- R. J. Cramer, A. Kehn, C. R. Pennington, H. J. Wechsler, J. W. Clark III, and J. Nagle, “An Examination of Sexual Orientation- and Transgender-Based Hate Crimes in the Post-Matthew Shepard Era,” Psychology, Public Policy, and Law 19, no. 3 (2013): 355–368; Bessel, “Preventing Hate Crimes”; J. Glaser, “Intergroup Bias and Inequity: Legitimizing Beliefs and Policy Attitudes,” Social Justice Research 18 (2005): 257–282; M. Sullaway, “Psychological Perspectives on Hate Crime Laws,” Psychology, Public Policy, and the Law 10 (2004): 250–292. ↵

- J. Spade and C. Willse, “Confronting the Limits of Gay Hate Crimes Activism: A Radical Critique,” Chicano-Latino Law Review 21 (2000): 41. ↵

- L. Ray and D. Smith, “Racist Offenders and the Politics of ‘Hate Crime,’” Law and Critique 12 (2001): 203–221; G. Mason, “Body Maps: Envisaging Homophobia, Violence and Safety,” Social and Legal Studies 10, no. 1 (2001): 23–44; Perry, “Where Do We Go from Here?”; F. M. Lawrence, Punishing Hate: Bias Crimes under American Law (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999). ↵

- McPhail, “Hating Hate,” 637, 645. ↵

- I. Meyer, A. Flores, L. Stemple, A. Romero, B. Wilson, and J. Herman, “Incarceration Rates and Traits of Sexual Minorities in the United States: National Inmate Survey, 2011–2012,” American Journal of Public Health 107, no. 2 (2017): 267–273; Center for American Progress and Movement Advancement Project, “Unjust: How the Broken Criminal Justice System Fails LGBT People of Color,” https://www.lgbtmap.org/file/lgbt-criminal-justice-poc.pdf. ↵

- M. Bassichis, A. Lee, and D. Spade, “Building an Abolitionist Trans and Queer Movement with Everything We’ve Got,” in Captive Gender: Trans Embodiment and the Prison Industrial Complex, ed. E. Stanley and N. Smith (Baltimore: AK Press, 2011), 17. ↵

The first ten amendments to the U.S. Constitution containing specific guarantees of personal freedoms and rights, clear limitations on the government’s power in judicial and other proceedings, and explicit declarations that all powers not specifically granted to the U.S. Congress by the Constitution are reserved for the states or the people.

Property that is movable; in terms of slavery, people are treated as the personal property of the person who claims to own them and are bought and sold as commodities.

A part of the Bill of Rights, this amendment addresses rights, retained by the people, that are not specifically enumerated in the Constitution.

A legal doctrine whereby, upon marriage, a woman’s legal rights and obligations are subsumed by those of her husband.

Adopted on July 9, 1868, as one of the Reconstruction Amendments, this amendment to the U.S. Constitution addresses citizenship rights and equal protection of the laws and is one of the most litigated parts of the Constitution.

A political approach that focuses on fixing the system from within, trying hard to fit into the status quo; integrating.

A U.S. federal law passed by the 104th Congress and signed into law by President Bill Clinton, defining marriage for federal purposes as the union of one man and one woman. The law allowed states to refuse to recognize same-sex marriages granted under the laws of other states. However, the provisions were ruled unconstitutional or left effectively unenforceable by Supreme Court decisions in the cases of United States v. Windsor (2013) and Obergefell v. Hodges (2015).

The Compton’s Cafeteria riot occurred in August 1966 in the Tenderloin district of San Francisco. The incident was one of the first riots concerning LGBTQ+ people in U.S. history, preceding the more famous 1969 Stonewall rebellion in New York City. It marked the beginning of transgender activism in San Francisco.

A series of spontaneous, violent demonstrations by members of the LGBT community against a police raid that began in the early morning hours of June 28, 1969, at the Stonewall Inn in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of Manhattan, New York City.

An act of the U.S. Congress that empowered the president to suspend the writ of habeas corpus to combat the Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacist organizations. Also known as the Ku Klux Klan Act.

In this case, also known as the Ku Klux Case, the U.S. Supreme Court held that it was unconstitutional for the federal government to penalize crimes such as assault and murder. It declared that the local governments have the power to penalize these crimes.

The portion of Section 245 of Title 18 that makes it unlawful to willfully injure, intimidate, or interfere with any person, or to attempt to do so, by force or threat of force, because of that other person’s race, color, religion, or national origin and because of their activity as a student at a public school or college, participant in a state or local government program, job applicant, juror, traveler, or patron of a public place.

A national organization dedicated to reducing violence and its impacts on LGBTQ+ individuals in the United States.