Private: Part VI: Culture

Chapter 11: LGBTQ+ Literature

Jennifer Miller; Maddison Lauren Simmons; Robert Bittner; Mycroft M. Roske; Cathy Corder; and Olivia Wood

Introduction

Queer desires have found their way into literature for thousands of years. Authors from ancient Greece and Rome, such as Plato and Homer, include love between men in their writing, and Sappho’s reputation as the mother of lesbian poetry is acknowledged by those who have never read her work.[1] By the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in Europe and the United States, representations extended beyond celebrating same-sex sexual and romantic desire to playing a vital role in the development of LGBTQ+ identities. In fact, the social development of LGBTQ+ identities runs through LGBTQ+ literature, as demonstrated by many of the sections in this chapter.

For instance, the American writer Walt Whitman’s poetry collection Leaves of Grass, a lifelong project first published in 1855 and continuously revised until his death, brims with erotic descriptions of men without ever characterizing same-sex desire as an identity. More blatantly queer is the British author Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness (1928), which tells the story of “invert” Stephen Gordon’s lesbian romance and her life negotiating social isolation and stigma as a result of her masculine gender presentation and desire for women. Similarly, the African American author James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room (1956) deals directly with issues of masculinity, homosexuality, and bisexuality through its thoughtful protagonist.[2]

Attempting to describe a canon of LGBTQ+ literature or to create a genealogy of texts spanning continents and centuries is an impossible task. Instead, this chapter explores specific fields of LGBTQ+ literature. Abiding by this limitation acknowledges that any survey of a field as vast and diverse as LGBTQ+ literature cannot be meaningfully cataloged in a single chapter. Students may wish to select one section and pair it with primary sources for an in-depth look at a field. The chapter focuses primarily, although not exclusively, on post-1950 work published in the United States to explore multiple fields of LGBTQ+ literature: children’s picture books, young adult novels, comics, pulp fiction, and memoir. Each section provides readers with a historical overview of the field and introduces readers to key terms, debates, and primary texts in the field. Each section also contextualizes the creation, publication, distribution, and reception of LGBTQ+ literature within a shifting sociocultural landscape. Readers will gain an understanding of social, political, and economic constraints and opportunities that have influenced the creation, distribution, and consumption of LGBTQ+ literature, which has always met with unique pressures from cultural gatekeepers.

Contributors to this chapter consider literature both a product and producer of history, and they suggest that literature plays an essential role in queer culture, community, and identity formation. The genealogical structure most sections adhere to allows readers to consider how literary content changes at different historical junctures. Even more, by reading two or more sections, similarities in content can be compared across fields. Additionally, each section identifies and describes key tropes that emerge in the field discussed. These tropes reflect shifts in societal attitudes about LGBTQ+ identities. For example, in pulp fiction and young adult literature, representations of gay and lesbian love have historically been tragic; happy endings have only recently begun appearing.[3] The quantity and quality of LGBTQ+ literature for young adults reflect shifts in social acceptance, which influences the publishing industry’s willingness to publish these books and the ability of teens to access them in bookstores, libraries, and even schools. It’s fair to say that LGBTQ+ literary and cultural texts are slowly making their way into dominant culture, which means more diverse representations and more positive representations are increasingly available to all readers.

Jennifer Miller’s section, “LGBTQ+ Children’s Picture Books,” maps the development of LGBTQ+ children’s picture books in the United States from the 1970s to the present. Maddison Simmons undertakes a similar project in “Tropes in Lesbian Young Adult Literature” as does Robert Bittner in “Trans and Gender-Nonconforming Characters in Young Adult Literature.” Both trace content shifts in representations of lesbian and transgender or gender-nonconforming youth in middle grade and young adult literature. All three sections demonstrate that representations of LGBTQ+ youth in books written for young people have contributed to parallel shifts in sociocultural understanding and acceptance of LGBTQ+ people. However, there is no linear path to progress; representations remain dominated by cisgender white middle-class gay men in young adult fiction, and middle-class white representations still dominate children’s literature, although transgender and gender-nonconforming characters are increasingly prevalent in the latter.

“LGBTQ+ Comics,” by Mycroft Roske and Cathy Corder, focuses on popular and underground U.S.-based comics. They consider how the 1954 Comics Code influenced queer representations in comics by forcing them underground. The Comics Code was prompted by the psychiatrist Fredric Wertham’s book Seduction of the Innocent: The Influence of Comic Books on Today’s Youth, which argues that comics turned vulnerable youth into delinquents.[4] Similar claims about the seductive power of culture have been used to justify censoring other forms of culture with a young audience, including film and picture books. Whereas cultural gatekeepers worked to censor comics, lesbian and gay pulp remained relatively free from the censor’s wrath. Cathy Corder’s “Lesbian and Gay Pulp Fiction” explores the melodramatic world of pulp, which often depicted young women and men in sex-segregated spaces falling in love. There are rarely happy endings in the realm of pulp, which tended to reproduce the trope of the tragic queer found across LGBTQ+ fields of literature. However, these books were formative in the lives of many gay men and lesbians at a time when few other representations existed.

The chapter’s last section, Olivia Wood’s “LGBTQ+ Memoir and Life Writing,” is unique in focusing on nonfiction books. Wood notes that because of homophobia and transphobia, LGBTQ+ life writing has only recently become available. She explains that life writing before the twentieth century was often in diary form and not meant to reach a public audience. In fact, according to Wood, LGBTQ+ memoirs produced for public consumption are a relatively new phenomenon that didn’t take off until the 1990s. Like the other sections in this chapter, Wood’s demonstrates that increased social acceptance of LGBTQ+ people has prompted increased representations.

This chapter does not represent LGBTQ+ literature in its entirety. Each section shares a snapshot of a particular aspect of LGBTQ+ writing as it has developed in the United States over the last several decades. This deliberate choice introduces important and engaging content to readers in a way that encourages meaningful exposure and exploration.

LGBTQ+ Children’s Picture Books

Jennifer Miller

LGBTQ+ children’s picture books use images and text to explicitly represent LGBTQ+ identities and experiences. They counter dominant sociocultural constructions of gender, sexuality, children, childhood, and family.[5] These texts contribute to a queer world-making project by rendering queer genders and sexualities visible, viable, and accessible to young audiences ranging from babies to twelve-year-olds. According to Jan M. Ochman, children’s picture books are a powerful socializing agent because they help children form a self-image, develop a sense of cultural expectations, and imagine inhabiting social roles.[6] In addition to doing important socializing work, LGBTQ+ children’s literature is a rich historical archive that reflects struggles occurring within culture to define the meaning and value of genders and sexualities that fall outside narrow and oppressive norms.

The best way to tell the story of LGBTQ+ children’s picture books is through the books themselves. This section examines English-language texts published in the United States and Canada between 1970 and 2018. It describes key texts and identifies key themes, as well as shifts in thematic content. It concludes with a brief discussion of how LGBTQ+ children’s picture books became an identifiable subfield within the category of children’s literature.

A Genealogy of LGBTQ+ Children’s Books Published between 1970 and 2018

Overt representations of LGBTQ+ identities and experiences are a fairly new occurrence in children’s picture books, which is why most queer scholarship about children’s literature seeks to uncover the queer potential in more readily available classic texts.[7] LGBTQ+ children’s picture books slowly began to appear in the 1970s, a trend that accelerated greatly after 2010.

1970s: Sissy Boys

A few books about boys who challenged gender stereotypes, a theme that remains popular, were published in the 1970s. The trend began with Charlotte Zolotow’s William’s Doll (1972), which is the story of a little boy who wants a doll. No one supports William’s desire for a doll, although his grandmother eventually buys him one. She appeases his angry father by explaining a doll will help William be a good father. The gay author Tomie dePaola’s Oliver Button Is a Sissy (1979) also tells the story of a boy who doesn’t enjoy typical boy things. Oliver is bullied at school because of his effeminate behavior. When his parents enroll him in dance he gains confidence and even acceptance from peers as a result of his talent. This book has a positive message, although it demands that pro-gay youth demonstrate exceptional behavior to be accepted by peers and family. The queerest of the 1970s trifecta of “sissy boy” books is Bruce Mack’s Jesse’s Dream Skirt (1979), which explores a boy’s desire for a skirt. Jesse’s mother accepts him as do his peers, who end up emulating his style.[8]

1980s: Lesbian Moms

Very few children’s books containing overt LGBTQ+ themes were available between 1979 and 1989. Jane Severance published two books with Lollipop Power Press, a small feminist press located in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, that published twenty-two books in its decade-plus of operation. When Megan Went Away (1979) is told from the point of view of a girl processing the separation of her mother and her mother’s partner. Her mother is emotionally unavailable during this period as she deals with her own pain. Lots of Mommies (1983) is about a girl raised communally by several women. Severance creates a robust cast of lesbian characters who provide the protagonist with a happy, albeit unconventional, home. Annie Jo is a carpenter, Vicki is a school bus driver, and Shadowoman is a healer. These texts are important historical artifacts of lesbian culture and lesbian cultural production in the late 1970s and early 1980s.[9]

In an email exchange on August 16, 2018, Jane Severance told me that she was only a few years out of high school when she wrote her first children’s book. She describes herself as “heavily involved in the women’s/lesbian movement, mostly concentrated on working at Woman to Woman Bookstore in Denver.” Severance observes that “parents were looking for books showing children with different families, children making nontraditional choices and being supported for making those choices.” It was in this context that Severance, with no training but a lot of passion, began writing. Severance received “a lot of flack” for showing a lesbian couple in an unflattering light in her first book, but Severance notes that lesbian mothers “were generally not supported, which meant that they couldn’t always make good parenting choices.” Her work is a product of the moment it records and in many ways is far more antinormative than many of the LGBTQ+ children’s picture books that followed hers and that remain in circulation.

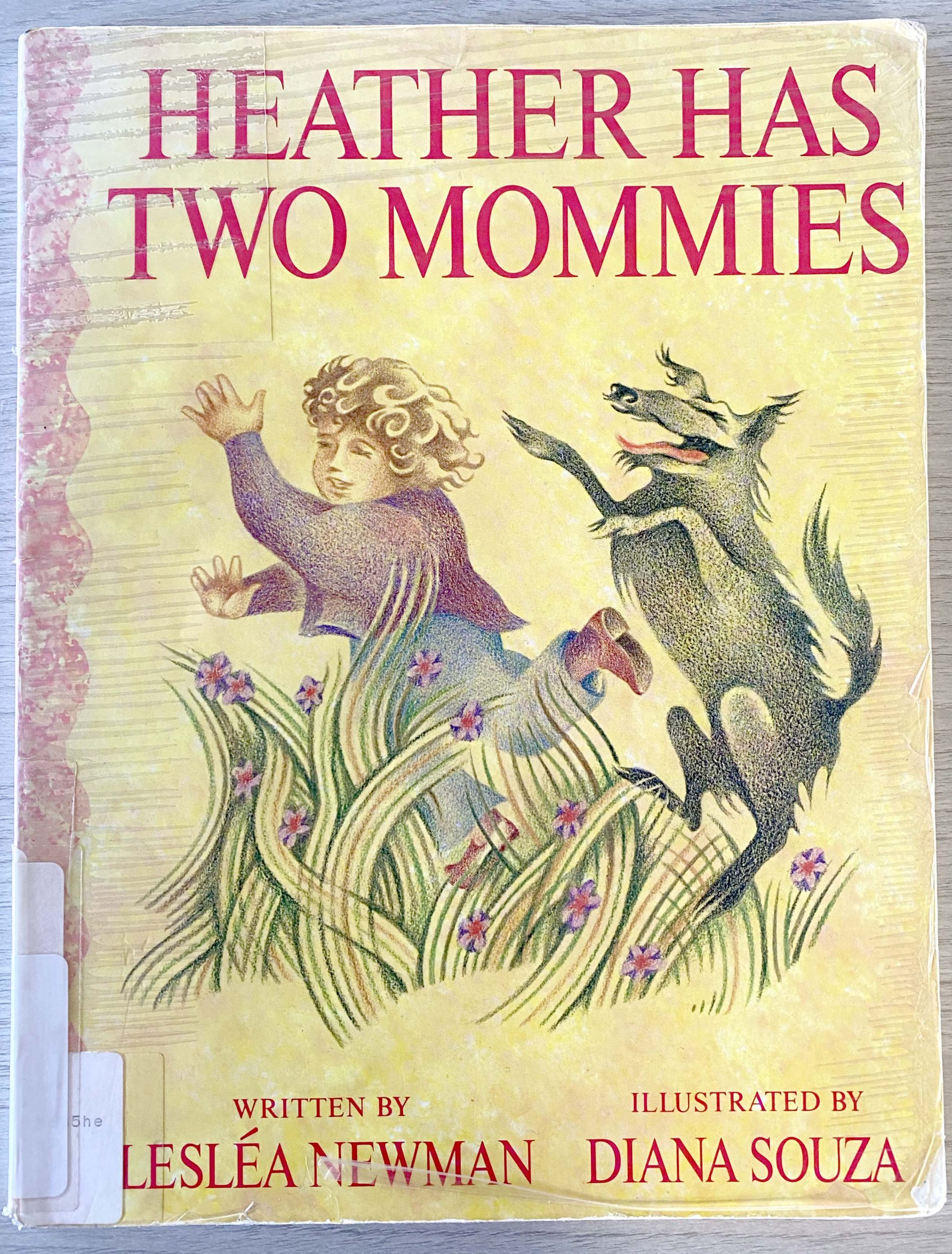

Lesléa Newman’s Heather Has Two Mommies (1989) (figure 11.1) inaugurated a new trend in LGBTQ+ children’s literature by representing lesbian families as patterned after heteronormative conventions. Importantly, Newman published Heather Has Two Mommies without the help of a traditional publisher. In an email exchange from January 28, 2019, Newman told me, “Though Heather Has Two Mommies isn’t self-published, I did actively participate in its publications. My business partner at the time, Tzivia Gover, and I came up with the term co-publishing. She had a desktop publishing business, and when no traditional publisher was willing to publish Heather, we decided to do it ourselves. We raised $4,000 via a letter-writing campaign, found an illustrator and a printer, and brought the book out in December of 1989.”[10] Micro presses and mission-driven (as opposed to profit-driven publishers) self-publishing continue to be a mainstay of LGBTQ+ children’s literature publishing. In fact, crowdfunding though platforms like Kickstarter are the latest tech version of the letter-writing campaign Newman used to fund her project.

1990s: Gay Uncles

Throughout the 1990s, small presses with a mission, such as Alyson Publications, which was founded in 1980 and created a children’s book imprint, Alyson Wonderland, in 1990, were at the forefront of creating LGBTQ+ children’s literature.

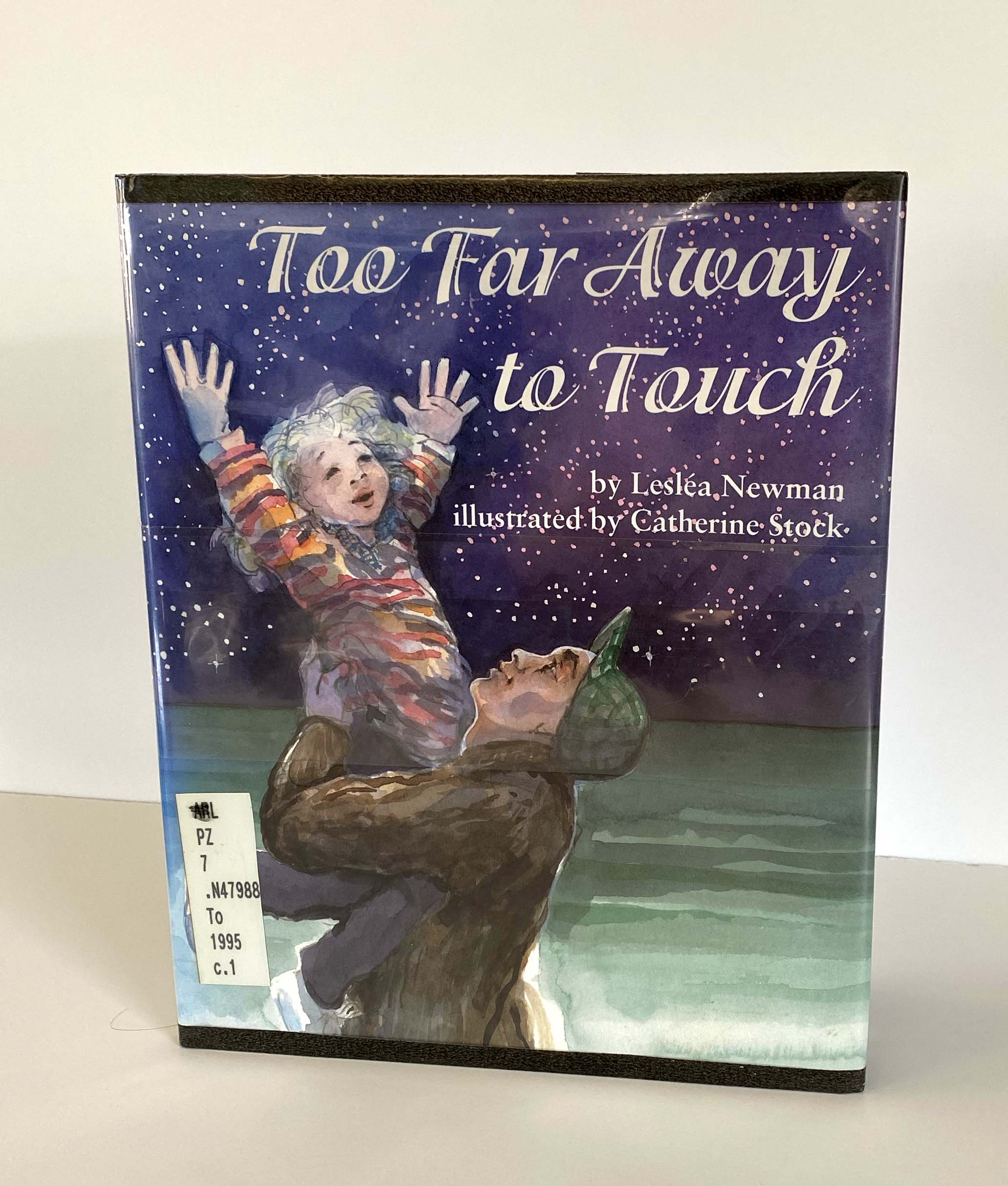

Books helping children understand and process loving and losing adults with HIV/AIDS began to appear in this period. A Name on the Quilt (1999), written by Jeannine Atkins and illustrated by Tad Hills, is the story of a family memorializing a beloved family member after his AIDS-related death. In the book, which is told from the point of view of the man’s niece, the family creates a patch for the AIDS Memorial Quilt. This is one of the few books that gesture toward gay community and activism while representing HIV/AIDS; most depict gay men in isolation, as outsiders within the heterosexual family unit. This is the case with Lesléa Newman’s Too Far Away to Touch (1995) (figure 11.2), in which a young girl’s uncle, who is ill from AIDS-related complications, helps her begin to process his eventual death by explaining that he will always be with her.[11]

My Dad Has HIV (1996) takes a different approach. It is an accessible text about HIV told from the point of view of a seven-year-old child whose father has the virus. The book was cowritten by Earl Alexander, an HIV/AIDS instructor, and two elementary school teachers, Sheila Rudin and Pam Sejkora. The father’s sexuality is never discussed, instead the book focuses on normalizing HIV/AIDS.[12]

That it took until the 1990s to see representations of HIV/AIDS make their way into children’s literature evidences the cultural lag that can be seen until around 2010, when LGBTQ+ children’s literature really became a site of advocacy and activism for LGBTQ+ youth.

2000s: Gay and Lesbian Parents

In the first decade of the 2000s, well-budgeted LGBTQ+ children’s literature that explored a variety of themes became the norm instead of the exception. Most of these books continued to focus on lesbian and gay adults through stories that focalized the experience of children related to them. Increased publishing opportunities eventually led to more diverse representations after 2010.

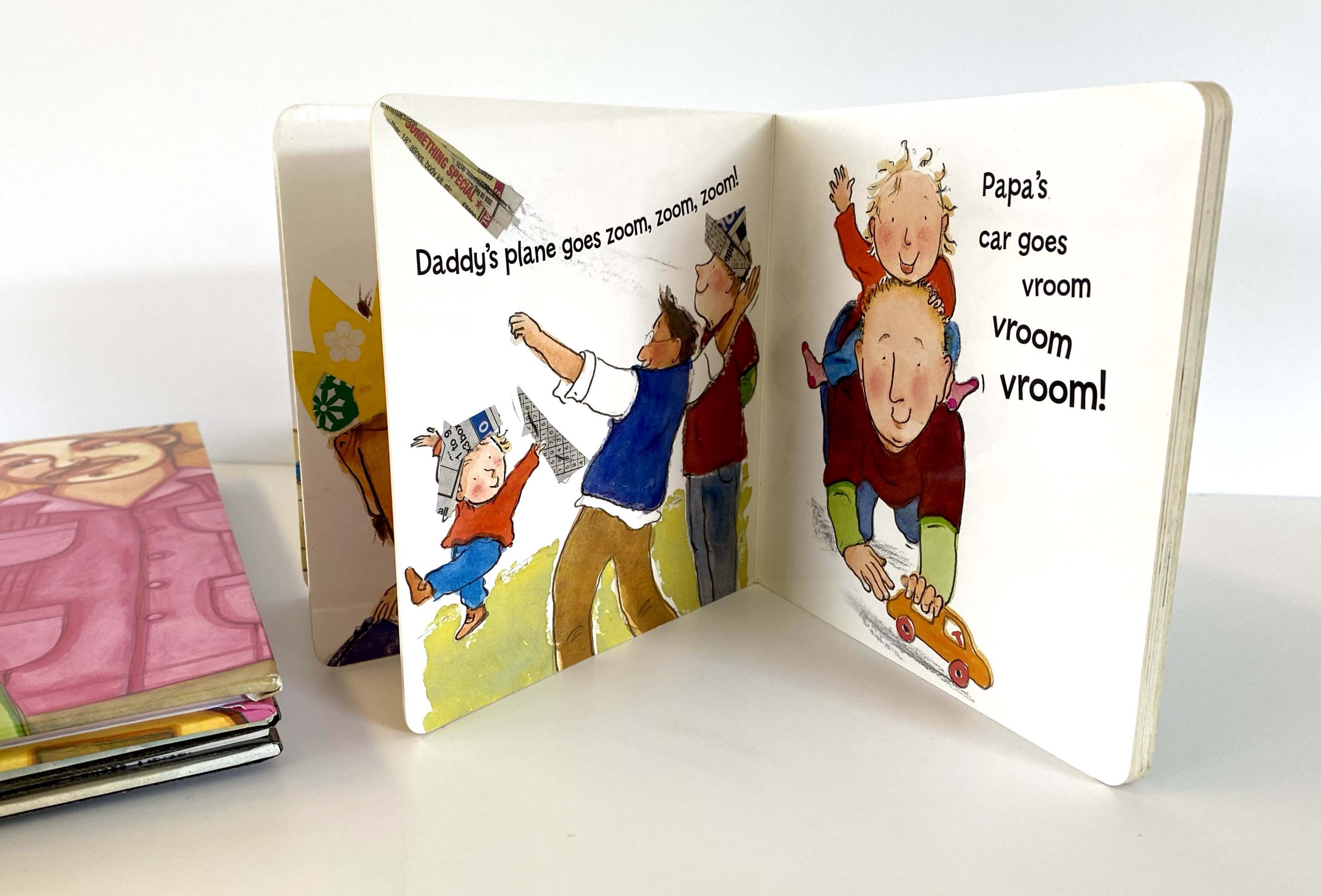

Lesléa Newman, the prolific author of Heather Has Two Mommies (1989) and Too Far Away to Touch (1995), continues to publish in the field. Her experiences negotiating the publishing industry reflect publishing shifts. She went from raising funds to publish her first book through a letter-writing campaign in 1989 to being solicited to create board books with LGBTQ+ themes in 2009. In our email correspondence Newman wrote, “I was asked by Tricycle Press to write a set of board books: one about a child with two moms and one about a child with two dads. Which I did. Tricycle was subsequently bought out by Random House, and the two books, Mommy, Mama, and Me and Daddy, Papa, and Me are still in print (10 years later!) and doing very well” (figure 11.3).[13]

Dozens of books about lesbian- and gay-parented families have been published since the 1990s, with most being writing after 2000. This increased social acceptance and public visibility of lesbian and gay families parallels political discussions about marriage equality and LGBTQ+ adoption. If traditional publishing companies with marketing and production budgets are now publishing LGBTQ+ content, that attests to the marketability of these books, not just to LGBTQ+ families but to all families who wish to provide their children with realistic windows into the world.

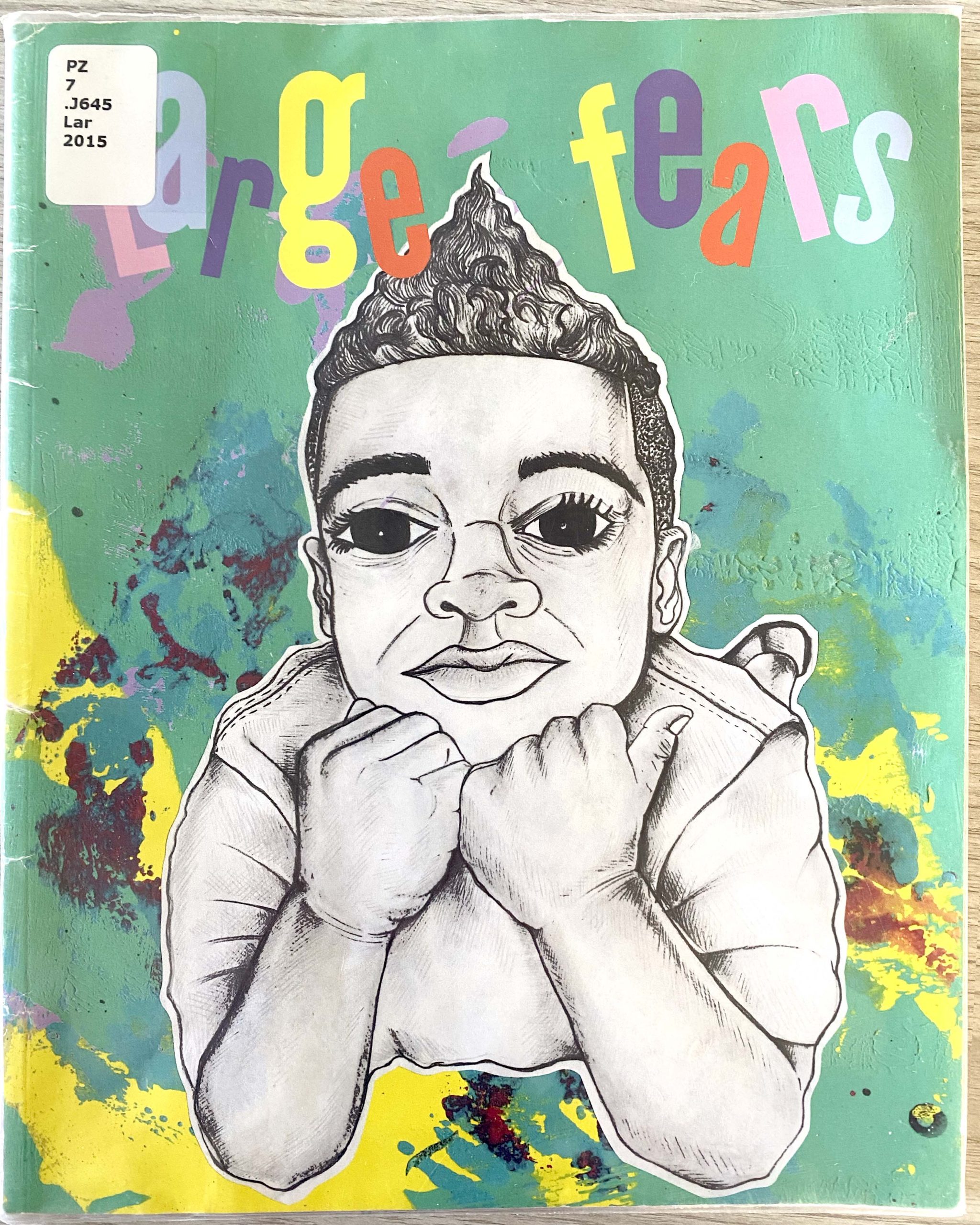

2010s

This is not to say that all queer content has found a home in traditional publishing or that traditional publishing is even desirable for all authors producing LGBTQ+ children’s picture books. For instance, Myles E. Johnson’s Large Fears (2015) (figure 11.4), a series of vignettes about Jeremiah, a queer Black boy who loves pink and wants to go to Mars, was crowdsourced.[14] In a 2019 Twitter exchange with me, Johnson said, “Crowdsourcing has limits, but it is perfect if you see a demand and just let the audience fund it instead of waiting on gatekeepers.” Johnson’s unique narrative style and focus on the subjectivity of a Black queer boy make pursuing traditional publishing, which primarily considers marketability and profitability, challenging.

Small, mission-oriented presses and self-publishing are still more likely than traditional publishers to publish content that intersectionally engages marginalized social identities. For instance, Inhabit Media, an Inuit-owned publishing company founded in 2006, published Jesse Unaapik Mike and Kerry McCluskey’s Families (figure 11.5), a picture book that affirms various family forms, including lesbian and gay families.[15]

Although a handful of books on transgender experience have been published traditionally, most continue to be published by nontraditional means. The very queer Flamingo Rampant, a Canadian micro press funded by crowdsourcing, explores queer gender and sexual identities as they intersect with other identity categories, including race and ability.[16] In one of their first publications, A Princess of Great Daring (2015), written by Tobi Hill-Meyer and illustrated by Elenore Toczynski, a transgender girl has not seen her friends all summer and prepares to share her gender identity with them for the first time. Jamie’s two moms drop her off at her friend’s house, and her friends are playing a game in which they save a princess from a dragon. Jamie offers to be the princess, and the boys are excited to have someone to rescue. Jamie interrupts the traditional narrative by declaring that she will be “a princess of great daring.” Concerned that they will have no one to rescue, one of the boys, Liam, volunteers to be captured by a dragon, but even the dragon defies gender expectations. She grabbed Liam only because she was lonely. When the game ends, Jamie’s friends tell her that she makes a great princess. She takes the opportunity to explain that she is a girl. They immediately accept her, and ask how they can best offer their support.[17]

Not surprisingly, in more traditional presses, marriage became an increasingly popular theme throughout the first and second decades of the 2000s, mirroring the increased visibility of sociopolitical debates about marriage equality. Sarah S. Brannen’s Uncle Bobby’s Wedding (2008) tells about Chloe, a little girl worried that her favorite uncle will have less time for her once he marries his partner. Extended family are accepting of the same-gender relationship, and Chloe comes around once she realizes the joy of having two uncles. Lesléa Newman’s Donovan’s Big Day (2011) (figure 11.6) also takes up the theme of same-gender marriage, this time through the point of view of a young boy whose mothers are marrying.[18]

Additionally, over the last several years, books have introduced very young readers to transgender and gender-nonconforming children, and to a lesser extent, adults have begun to appear. For instance, Worm Loves Worm (2016), written by J. J. Austrian and illustrated by Mike Curato, is a candid story about two worms who fall in love and wish to marry. Their insect and arachnid friends demand they jump through all the traditional hoops, including getting rings even though they don’t have fingers and buying a cake even though they eat only dirt. They go along with everything until it comes to choosing who will wear the white wedding dress and who will wear the tuxedo. At that point, the worms queer gender expectations when one wears the dress with a top hat and the other wears the tuxedo with a veil. Another example, Square Zair Pair (2015), written by Jase Peeples and illustrated by Christine Knopp, takes place in a fantasy world inhabited by Zairs. Zairs hatch from eggs that grow from vines. Some are tall and square; others are short and round. Round and square Zairs always form a pair by attaching tails. One day two square Zairs pair. The community is outraged and demands they leave the group, using rhetoric like that of the real-world Right. After the exiled Zairs save the other Zairs from starving during an unexpected winter storm, they are accepted back into the community, which echoes the demand for queers to be exceptional to be accepted.[19]

Stories about same-gender-desiring children are also (slowly) beginning to appear. In Thomas Scotto’s Jerome by Heart (2018) two boys share an affectionate friendship that makes the adults in their lives uncomfortable. This is one of only two representations of same-gender love between children available in children’s picture books.[20] E. J. Martinez’s When We Love Someone We Sing to Them: Cuando Amamos Cantamos (2018) is the other (figure 11.7). It is a joyful celebration of father-son relationships and young love. Martinez’s depiction of the Mexican serenata tradition subtly queers custom.

It was not until 2009, with the publication of Cheryl Kilodavis’s My Princess Boy, that transgender and gender-creative children began appearing in children’s picture books. The gender-creative protagonist, who is never named but instead referred to by the narrator-mother as “my Princess Boy,” seems to be effortlessly accepted by family and friends. This book and others like it break out of the sissy-boy mold present in earlier books by representing gender-nonconforming boys who enjoy toys and activities associated with girls as accepted by family and peers.[21]

Two years later, the gay author Marcus Ewert published one of the first children’s picture books, 10,000 Dresses (2011), illustrating the experiences of a transgender girl. The child, Bailey, is bullied by family members who insist she is a boy even though she knows she’s a girl. Rex Ray illustrates the text, providing the reader access to Bailey’s inner life by depicting her dreams and thoughts. Every morning when Bailey wakes up, she tells a family member about the dress-wearing dream she had the previous night. Every morning a new family member dismisses her dream, ignores her attempt at self-definition, and tries to silence her. After her brother threatens her with physical violence, Bailey runs away from him. She meets an older girl named Laurel who is the only character besides Bailey who is given a name and face. The two girls create beautiful dresses together. The final image is of the girls wearing the dresses they worked together to make. The book alludes to chosen families through Bailey’s experience of rejection by her heterosexual family and the support she finds with Laurel.[22]

I Am Jazz (2014) is an autobiographical children’s picture book coauthored by Jessica Herthel and the title character, Jazz Jennings. Jennings, now a young transgender woman with her own TLC show, first entered the spotlight in 2007 when she was featured on a 20/20 documentary about transgender children. This book is a significant contribution to LGBTQ+ children’s literature because it is coauthored by and narrated from the perspective of the transgender child protagonist.[23]

LGBTQ+ books published in the last few years demonstrate how social and cultural visibility of LGBTQ+ youth has increased. Representations that affirm LGBTQ+ youth especially reflect medical models of care for young queer people that better meet their needs.

The Making of LGBTQ+ Children’s Literature

The conversations that surround LGBTQ+ children’s literature, specifically, challenges and celebrations of its existence, are an important part of the field’s story.

The internet has played a critical role in increasing the visibility of LGBTQ+ identities and aiding postmillennial queer community building. Blogs by book reviewers, parents, teachers, social workers, and librarians have provided a virtual grassroots campaign to spread the word about LGBTQ+ children’s books. For instance, Mombian: Sustenance for Lesbian Moms is a parenting blog that was founded in 2005 when the creator noted “a lack of sites with current, practical news and information for LGBTQ parents, or sites that looked at other aspects of LGBTQ culture with a parent’s eye.”[24] The blog contains a wealth of information about LGBTQ+ children’s culture and smart reviews of dozens of books.

The recent emergence of literary awards provide LGBTQ+ children’s literature a degree of respectability and authority. For instance, the Stonewall Book Award, which is administered by the American Library Association’s Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Round Table, was established in 1971, but a Children’s and Young Adult Literature Award was not created until 2010. The Lambda Literary Awards began acknowledging and awarding LGBTQ+ authors and writers of LGBTQ+ content in 1989 and created a category for Children’s and Young Adult Literature in 1992. Awards lend legitimacy to the subfield. Both of these relatively new awards help LGBTQ+ children’s books get the accolades they deserve.[25]

Less affirming discourses predate blogs and awards. Children’s literature has many gatekeepers: parents, educators, librarians, even publishers themselves. Representations of lesbian, gay, and transgender experiences, expressions, and identities remain some of the most contested within the world of children’s literature. According to the American Library Association, two of the top ten most contested books of the 1990s represented queer parenting: Daddy’s Roommate, by Michael Willhoite, and Lesléa Newman’s Heather Has Two Mommies.[26]

Controversies over LGBTQ+ children’s literature are hardly a thing of the past. In the 2010s, myriad attempts to keep books with LGBTQ+ content out of libraries and classrooms have sprung up across the United States as well as globally. In Kansas there were attempts to remove I Am Jazz and other books with transgender characters from libraries. Attempts have been made to ban the books of LGBTQ+ children’s picture-book author Gayle Pitman in Colorado, Texas, and Illinois.[27]

The political, cultural, and personal significance of LGBTQ+ children’s picture books can be best understood by cataloging responses to it. Like the texts themselves, discourses that challenge and discourses that celebrate the work are critical archives of feeling and practice that reflect shifting social and cultural responses to LGBTQ+ identity.

Tropes in Lesbian Young Adult Literature

Maddison Lauren Simmons

To explore the rising importance and acceptance of the LGBTQ+ community and uncover tropes and themes, this section examines lesbian young adult fiction, novels written for twelve- to eighteen-year-olds, that have a lesbian protagonist. Eight popular and accessible U.S. novels written since the 1970s are the basis of this examination, with one or two books selected from each decade. All include a woman attracted to other women, with most of them being clear that the character is a lesbian (or in one case, bisexual). In the discussion, queer refers to cisgender women who identify as lesbian, bisexual, pansexual, or queer.

The first lesbian-specific young adult novel was not published until 1976, Rosa Guy’s Ruby.[28] According to Christine A. Jenkins and Michael Cart, the general types of stories with queer characters published between 1969 and 2016 had one of three themes: “homosexual visibility,” “gay assimilation,” or “queer consciousness/community.” Homosexual visibility refers to a character coming out and the tension that “might happen when the invisible is made visible.” Gay assimilation involves a “melting pot of sexual and gender identity,” and these stories involve characters who “just happen to be gay” but it’s not their main characteristic. Finally, stories that involve queer consciousness “show LGBTQ+ characters in the context of a community.”[29] Although the homosexual visibility category is seen in nearly every novel, gay assimilation novels were more common in the 1990s to early 2000s, and stories with queer communities were more common after 2000. This could be due to changing attitudes with respect to the queer community over the decades. Novels closer to the 2020s have more positive and diverse queer representation.

Like LGBTQ+ literature more generally, lesbian young adult fiction tends to fall into one of the three categories Jenkins and Cart introduce. In addition, the narrow field of lesbian young adult fiction includes these tropes: (1) the Miserable Lesbian, which refers to lesbians depicted as unhappy and lonely, (2) the Lesbian Victim, who has experienced acts of homophobia and violence as punishment for her sexuality, (3) the Confused Parents, who think that they did something wrong while raising their daughter and that’s why she’s gay, or they think that someone turned their daughter gay, (4) Lesbian Self-Discovery, in which she feels right with her sexuality and queer love interest, and (5) Found Family, focusing on the importance of friends and on those in the queer community triumphing over hardship and coming together as a family when the biological family of a queer person is lacking.

The earliest lesbian young adult novels are littered with unhappy and lonely queer characters, secret relationships, and violence against the lesbian characters. Of the eight books examined for this project, the stories published in the 1970s and 1980s (and even some into the early 2000s) exhibited these tropes of the miserable lesbian and the lesbian victim, but they accomplish the homosexual visibility and gay assimilation that Jenkins and Cart defined. Although they may have been unhappy, queer characters were at least there, allowing some sort of visibility, even if the queer character didn’t get a happy ending. This is important because it showed lesbian characters during a time when the LGBTQ+ community was not accepted in general society. Between the 1970s and early 2000s, novels that enfolded the beliefs of society at the time encountered less pushback than those featuring an out and proud lesbian who had no problems with her sexuality. People expected lesbian and queer characters to face setbacks because of their sexuality, but as they became more represented and accepted, over time the stories about queer characters were able to evolve from miserable lesbians to lesbians who are out and proud and facing little to no pushback for their sexuality.

Rosa Guy’s Ruby (1976) is often heralded as the first lesbian young adult novel. In the book, eighteen-year-old Ruby Cathy and her family move from the West Indies to Harlem, New York. The story describes the family’s adjustment to Harlem and Ruby’s budding relationship with Daphne Duprey, a self-confident and charming girl in Ruby’s classroom. Ruby is described as a terribly lonely girl plagued by sadness, but she sees Daphne as a way to escape her loneliness. Although the story doesn’t touch on lesbianism much and never explicitly defines Ruby as a lesbian, this was the first young adult novel that involved a relationship between two women. This book is a great example of Jenkins and Cart’s homosexual visibility because, although Ruby is not happy, at least her story was published and people could read about a young queer woman and her relationship with another woman.

Julie Anne Peters’s novel Keeping You a Secret (2003) is about Holland, the protagonist, realizing she has feelings for a girl named Cece and their eventual relationship. This novel harks back to the miserable lesbian trope of earlier years because Holland gets kicked out of her house once her mother learns about her and Cece. But it also anticipates the presence of queer community, because Holland uses local queer resources to move into a queer-run apartment complex. This novel includes the confused parent, lesbian victim, and self-discovery tropes and falls in line with all three themes of Jenkins and Cart. Although her life seems bleak after she is kicked out, Holland believes that one day things will be okay and she will have a home, pride, and acceptance within the queer community.[30]

By the early 2010s, the queer community theme and found family trope are widely used. Published in 2012 but set in 1990, The Miseducation of Cameron Post, written by Emily M. Danforth (figure 11.8), is set in a conversion therapy camp. This story involves the miserable lesbian, lesbian victim, and found family tropes and falls into Jenkins and Cart’s queer community category. Although the camp itself is extremely toxic and is meant to break down the very essence of who each camper is in order to convert them to heterosexuality, the friendships formed between the more rebellious campers are a saving grace in a place where they would otherwise lose sight of who they are. As the first semester at the camp comes to an end, all the campers go home to their families during winter break. After spending months with new people and having practically zero contact from her life before, Cameron notes how strange it feels to be leaving camp. She realizes that the camp has become home, but more specifically, she realizes just how important the friendships she made have been. Despite the circumstances that brought them together, Cameron feels closer to the other campers than she does to her aunt, who sent her to the camp. This shows that, even though this type of camp was meant to strip away the essence of who a queer person was, it didn’t always work and sometimes created stronger friendships and a strong found family.[31]

These Witches Don’t Burn (2019), written by Isabel Sterling, is about a teen witch named Hannah who has to deal with her ex-girlfriend and an attack on her coven while managing life as a teenager. This novel is filled with positive representations of queer characters, and Jenkins and Cart’s theme of queer community is very present in this novel. The trope of self-discovery is also prevalent, but because Hannah is an out lesbian from the first page, the trope focuses more on her feeling right with her new love interest than on wrestling with her sexuality. A lot of queer characters throughout These Witches Don’t Burn show queer consciousness and the importance of positive queer representation. There are lesbian neighbors who are married and expecting a child, there’s a trans coworker at Hannah’s job, and various other queer students. When Hannah first meets her new coworker Cal, she slips up and mentions her ex and then has to say that her ex is another woman. She immediately is nervous, her internal monologue saying, “Coming out is always nerve-wracking, no matter how many times I do it.” Cal then comes out to her, mentioning an ex-boyfriend of his and that he’s trans, and Hannah recalls “instantly feeling a tighter kinship with my new coworker, like seeing a familiar face in a crowd of strangers”[32] There’s a powerful dynamic when queer people meet in a public space and recognize that the other is queer. When two queer characters meet in a story and recognize that the other is queer, it lets readers know that nothing bad is going to happen to them (at least with the other person) because of their sexuality.

When LGBTQ+ people are not accepted by their birth families, stories of found families and queer communities resonate deeply. These tropes and themes are important not just as story elements but for queer readers to see themselves in fiction. Even with the ruling of Obergefell v. Hodges in 2015, which legalized gay marriage in all fifty states, there are still homophobic people who don’t support queer people. Although society is generally becoming more inclusive and welcoming of different people, not everyone is lucky enough to be loved and supported by their biological family when they come out. Queer friendships are usually stronger than other types because most queer people live with the fear that they will eventually come in contact with someone who hates them just because they’re queer. Finding another queer person and creating a found family that provides safety, love, and support is an incredibly important event in real life and in literature.

The trope of self-discovery and feeling right with a queer partner is in nearly every novel of this project. The character deals with their sexuality or, if they were already out, with their feelings for another woman. In Annie on My Mind (1982) and Keeping You a Secret (2003), especially, in a moment of gay panic, the main character slowly realizes she is queer and freaks out, but her worries melt away once she kisses her love interest and feels that nothing had ever been more right or made as much sense. In the novels published after 2010, there is less of this gay panic and more nonchalance about sexuality, because the main character was usually already aware of her sexuality and okay with it.[33]

Even if the story has many pitfalls and trials for the queer characters, at least each novel mentions that being with the right person, no matter their gender or sexuality, feels right and good and brings peace. It’s something that most people can relate to, and it’s a powerful sentiment that normalizes queer relationships by implying that queer people and queer relationships are not inherently disgusting or wrong. Allowing queer characters the same ability to find Mr. or Ms. Right, but of the same gender, normalizes queerness in a heteronormative society.

Since the 1970s, lesbian young adult novels have moved away from the miserable lesbian trope and toward happier lesbian characters who find a strong queer community and feel love and acceptance. The trend of the tropes and themes discussed here suggest that, one day, queer experiences will be filled with less tragedy, but until then, literature will continue to have a strong queer community and an influx of queer-affirming stories.

Trans and Gender-Nonconforming Characters in Young Adult Literature

Robert Bittner

Literature for young readers fluctuates constantly to reflect and speak to the experiences of children and teens in different geographic and community-oriented contexts, changing—sometimes rapidly, as in the case of gender and sexuality—over time as the sociopolitical landscape shifts.[34] Literature reflecting the realities of LGBTQ+ youth is indeed very reactive to the sociopolitical landscapes in which it is written and published. As queer and trans acceptability grows in mainstream media and the political landscape, so too does representation increase in the literature published for young people.

This section focuses primarily on literature produced between 2000 and 2020 for middle grade readers, between the ages of eight and twelve, and young adult readers, between the ages of twelve and eighteen. Starting with a look at where transgender representation in young adult literature began, this chapter then follows a time line of transgender and gender-nonconforming representation in middle grade and young adult literature, highlighting the evolution of gender identities in these years. The last part of the chapter explores tropes—commonly used themes or literary devices that can become cliché over time—within trans and gender-nonconforming narratives and how they can be problematic.

Beginnings

The year 2004 is often cited as the beginning of transgender representation in literature for young adults, and in many respects, this is true. In this year Luna, the first young adult novel with a transgender character, was published, but it was not the first instance of a transgender character in young adult fiction.[35] That distinction is given, as Jenkins and Cart note, to Francesca Lia Block’s short story “Dragons in Manhattan,” published in her 1996 collection Girl Goddess #9.[36] They further note that although the story itself is young adult, the trans character is an adult, unlike the vast majority of trans characters in young adult literature today.

Five years after Block’s short story, Emma Donoghue published “The Welcome” in Michael Cart’s edited collection Love and Sex: Ten Stories of Truth (2001).[37] Both Block’s and Donoghue’s short stories feature trans women, as does Luna. These firsts are to be commended for paving the way for future transgender and other gender-nonconforming characters, but since that time, scholars have noted the problematic nature of these early representations, particularly in Luna, mostly due to the emphasis on Luna’s sibling, rather than Luna herself, and also because Luna is portrayed as a burden to her family and friends throughout the novel.

The existence of other gender-nonconforming characters in young adult literature is a relatively new phenomenon spanning just over two decades, even less when looking only at full-length novels. With this in mind, the many varieties of gender identities now represented is impressive, especially considering how long it took to move beyond gay and lesbian characters.[38] Since Luna, there has been greater inclusivity of characters who are not cisgender, including transgender, genderqueer, intersex, bigender, nonbinary, and two-spirit representation.

These diverse gender representations are important for many reasons. Rudine Sims Bishop notes in her work on children’s literature that books function as mirrors and windows.[39] Diverse representation, therefore, allows more young readers to see themselves reflected in the books they read, thus reinforcing that their existence is legitimate and worthy of deeper exploration in literature. As windows, literature for young readers allows a glimpse into the lives and worlds of others. This is the lens through which the remainder of this section is constructed, thereby emphasizing the necessity and impact of diverse representations of gender in young adult literature.

A Time Line of Firsts

Building on the momentum from the publication of Luna (2004), Ellen Wittlinger wrote Parrotfish (2007)—the first instance of a trans man in young adult literature—which follows Grady in his physical and mental transition while dealing with an unaccepting family (figure 11.9). Two years later, Brian Katcher’s novel, Almost Perfect (2009) arrived on the scene and won a Stonewall Book Award from the American Library Association, the oldest and largest U.S.-based professional organization for librarians. Katcher’s novel began to gather more negative reviews from trans teens over the years following its publication, however, because of the many stereotypes the narrative relies on. In the same year, the novel Punkzilla (2009) by Adam Rapp was published and two more short stories came out in Michael Cart’s edited collection How Beautiful the Ordinary: Twelve Stories of Identity (2009).[40]

Another first occurred with the publication of I Am J by Cris Beam in 2010 (figure 11.10). J is assigned female at birth and is looking for medical intervention to transition, but because he is not eighteen and his parents don’t know that he is trans, he cannot legally access hormone treatment. But what makes this novel a first is that J is both Jewish and Puerto Rican, making this the first instance of a nonwhite transgender teen in young adult literature.[41]

A banner year for literature for trans and gender-nonconforming young adults, 2012 saw the publication of three novels with transgender characters and the first instance of a two-spirit secondary character. Happy Families by Tanita S. Davis explores the lives of a Black family as their father comes out as transgender, and Rachel Gold’s Being Emily (2012) follows Emily as she is forced into reparative therapy to “cure” her transness.[42] Emily Danforth’s The Miseducation of Cameron Post (2012) also focuses on conversion therapy, and although it focuses on a lesbian protagonist, Danforth includes a two-spirit character named Adam.[43] Last, Kirstin Cronn-Mills published the Stonewall Book Award–winning Beautiful Music for Ugly Children (2012).[44]

In 2013, Kristin Elizabeth Clark published Freakboy, a novel in verse from the perspectives of three different characters, two of whom are transgender. Another book, Two Boys Kissing by David Levithan, features alternating chapters from the perspectives of different characters, one of whom is transgender, which revolve around an attempt by two boys to break the world record for longest kiss.[45]

Middle grade literature saw its first transgender protagonist in 2014 with Ami Polonsky’s Gracefully Grayson. Additionally, For Today I Am a Boy, by Kim Fu, includes the first Asian trans protagonist (figure 11.11). But what makes 2014 stand out, in addition to these texts, is that the first instance of an intersex character appeared in Bridget Birdsall’s Double Exposure, in which Alyx struggles to understand and accept her body and her gender in a world of binaries. This year also saw the publication of a pair of trans young adult memoirs by Katie Rain Hill and Arin Andrews. Hill’s Rethinking Normal and Andrews’s Some Assembly Required explore the lives of these teens both individually and during the time that they were dating each other. These books started a small wave of trans young adult memoir over the next five years. A further nonfiction title, Beyond Magenta, by Susan Kuklin, features the stories of trans youth and the challenges they face every day living in the United States.[46]

Another transgender middle grade novel, George, came out in 2015 (figure 11.12). The book was written by Alex Gino, a genderqueer author, and garnered a number of awards. In 2021, the book was retitled Melissa to show respect for the protagonist’s gender identity. Robin Talley published What We Left Behind (2015), about Toni, a character questioning their gender.[47] According to Jenkins and Cart, within this novel “every conceivable word in the transgender vocabulary is bandied about, dissected, and analyzed,” making this novel not only enjoyable but also informative.[48] Two more intersex protagonists also showed up on the scene: Alex as Well (Alyssa Brugman, 2015) and None of the Above (I. W. Gregorio, 2015). And to make 2015 even more exciting, Pat Schmatz published Lizard Radio, featuring a nonbinary protagonist.[49]

If I Was Your Girl (2016) was the first young adult novel written by a transgender author, Meredith Russo. That same year, Jeff Garvin published Symptoms of Being Human (2016), a novel focusing on a gender-fluid teen who explores expectations of a binary world both in high school life and online through a series of blog posts. Anna-Marie McLemore published a highly decorated novel called When the Moon Was Ours (2016), which features dual protagonists, one of whom is trans. Girl Mans Up (2016), a novel about a gender-nonconforming teen by Canadian author M-E Girard, was also published the same year.[50]

Books like Lizard Radio and When the Moon Was Ours showed the possibilities of combining trans narratives with genre fiction, a trend that continued into 2017 with Dreadnought by April Daniels and Mask of Shadows by Linsey Miller. An acclaimed nonfiction book by Dashka Slater, The 57 Bus (2017), chronicles the true story of a young trans girl whose skirt was set on fire in a prank and the young Black man who was painted as a monster in the wake of the crime. Jaya and Rasa, by Sonia Patel, a novel set in Hawaii, explores not only gender but also the plight of young sex workers. Another middle grade novel, Felix Yz, by Lisa Bunker, features a gender-fluid grandparent who goes by Grandy.[51]

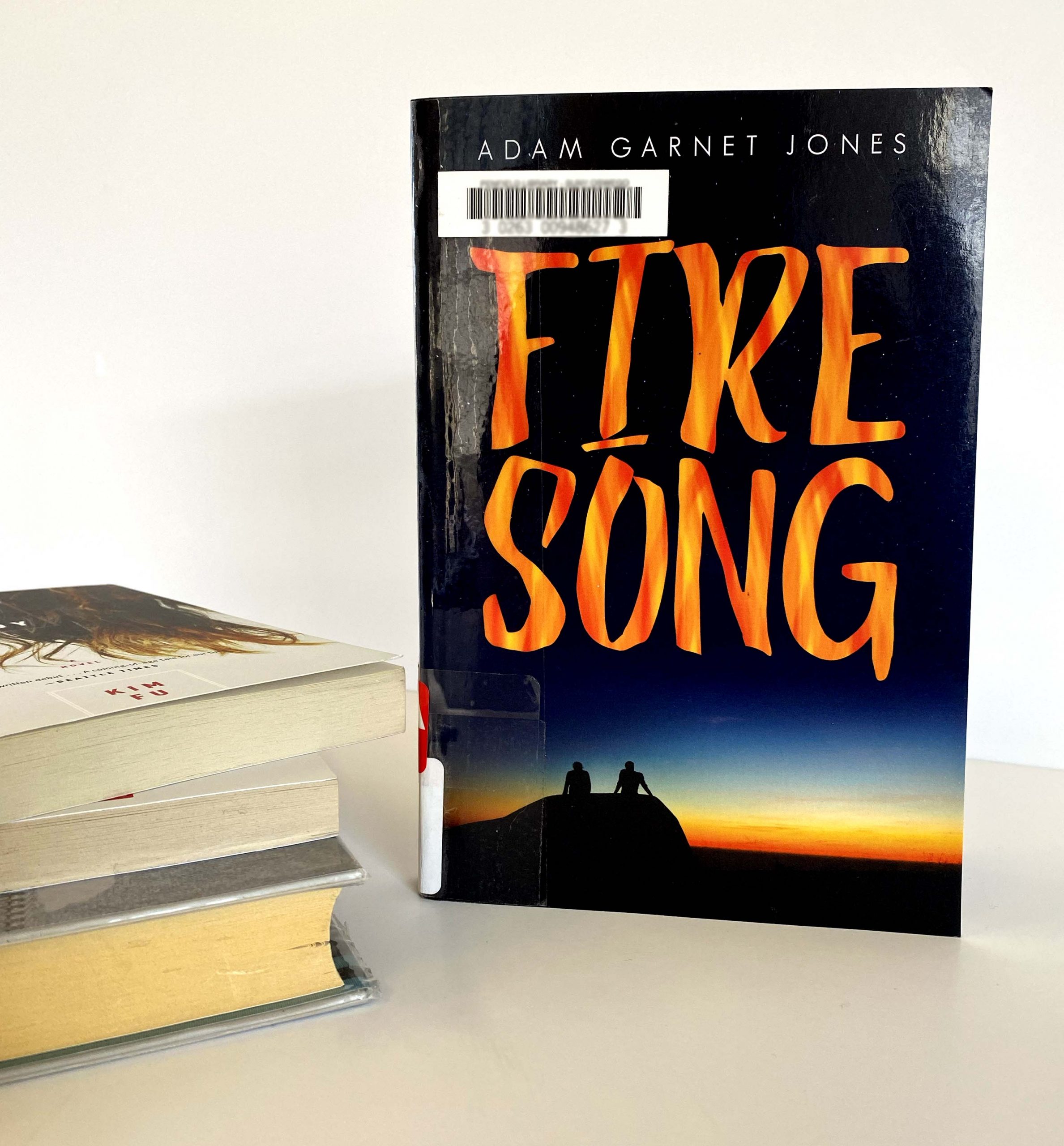

In 2018, Adam Garnet Jones adapted his feature-length film into a young adult novel called Fire Song, which features Canadian Indigenous queer youth and looks at gender roles and gender expectations within that context (figure 11.13). Mason Deaver brought out another nonbinary character in I Wish You All the Best in 2019, and what makes it even better is that Deaver is a nonbinary author. Kings, Queens, and In-Betweens, by Tanya Boteju, features drag, gender questioning, and explorations of gender nonconformity with a diverse cast of primary and secondary characters.[52]

Two 2020 novels bringing new gender identities into mainstream young adult fiction are Kacen Callender, who writes about a demiboy in Felix Ever After, and in Somebody Told Me, Mia Siegert examines what it means to be bigender.[53]

Many more new and emerging identities no doubt will be featured in the coming years, and considering how long it took from the emergence of queer literature for teens in 1969 to the first trans young adult novel in 2004, there has been a huge change in what is included under the umbrella of gender and sexual diversity in literature for teens. However, because there are still so few representations in the larger landscape, it is necessary to understand at least a few of the common and problematic tropes that exist in the body of transgender and gender-nonconforming literature for young adults. And along with those tropes, the overwhelming majority of existing young adult and middle grade fiction revolves around white middle-class suburban families under the umbrella of contemporary realistic fiction, making it difficult to even find racial and class diversity among trans and gender-nonconforming representation.

Tropes and Troubles

Many trans young adult novels until very recently have been written by cisgender authors, and therefore a large majority of earlier young adult novels feature tropes such as the wrong-body narrative in which being transgender is described almost entirely as being born into the wrong body. Although some trans people may feel this way, many do not, and for nontransgender audiences to see this trope time and again can reinforce the idea of a universal trans experience. Other tropes discussed here include the acceptance narrative, the hero’s journey, and the focus on physical transitioning in middle grade and young adult novels featuring trans and gender-nonconforming young people.

Clarence Harlan Orsi notes in the Los Angeles Review of Books, “A lot has changed for trans people in the last 15 years, yet the novels reflect a relatively unified perspective. . . . After reading only a handful of these books . . . , I could usually predict what would happen next.” He continues, “In the end, though, . . . they teach the kids (and parents) who read them what it means to be trans.”[54] When young adult novels and other forms of mainstream media continue to push the same tropes over and over again, audiences construct a false understanding of trans lived experiences, including the idea that trans existence is defined by physical and psychological trauma. Brian Katcher’s novel makes for an almost perfect (pardon the pun) jumping-off point to better understand other common tropes.

Almost Perfect is an award-winning novel, but its narrative arc and character descriptions follow what steadily became a well-worn trope thanks to Luna and Parrotfish. These early novels, and many since, follow a trope that Vee Signorelli calls the acceptance narrative, in which the focus is on cisgender characters and their ways of coping with transgender people in their lives. Even when the novels have trans narrators, they are still often focused on the reactions of cisgender peers or family members. Signorelli claims that in the acceptance narrative trope, cisgender characters often realize they have been horrible to trans people and should be nicer, but not until after many years of torment and trauma.[55]

In 2016, Signorelli expanded on the acceptance narrative, explaining a slightly more nuanced, but still problematic, trope in young adult literature: the hero’s journey. This trope seems more hopeful at first; the trans character tends to be the hero of their own story, and they often end up in a more hopeful place at the end. But within the main narrative arc, the trans character still endures hardship in the form of physical or psychological trauma. With both of these typical narrative trajectories involving violence toward trans characters, the ultimate message for young readers is that it is impossible to exist as a transgender or gender-nonconforming person without inevitable trauma. As Signorelli notes, “Over and over again, our pain is used, and misrepresented. To make the very people who make this world so terrifying for us feel good about themselves.”[56]

Even in memoir and other nonfiction, texts tend to focus on physical transition, medical intervention, and navigating trauma, which in turn raises the question: Who are these books for? With fictional trans characters and trans teen memoir focusing mostly on the transgender body, readers are left with the idea that being trans is entirely about the physical self, not about other aspects of life and enjoyment. It seems that much of the existing literature is still written to educate nontransgender readers rather than tell individual stories where trans characters can experience joy, purpose, and fulfillment.

Because so many novels follow this path, the idea of a universal trans experience means that existing literature may seem diversified on the surface, but underneath, the core of many trans young adult narratives is the same. Novels such as those by Deaver, Callender, Gino, and even those by trans youth themselves, like Katie Rain Hill and Arin Andrews, attempt to break free from the universality of so much existing representation. By using personal experiences—as trans and gender-nonconforming individuals—these authors can mirror their experiences within the literature that they create, thus allowing for more accurate and nuanced representation of trans and gender-nonconforming lives.

Things are certainly improving, but there is still a long way to go.

LGBTQ+ Comics

Mycroft M. Roske and Cathy Corder

Graphic narratives—stories told through sequential images with words—come in many forms: comic strips, superhero comics, graphic novels, manga, and more. Whereas the format of a picture story goes back centuries, our notion of comics is primarily a twentieth-century development.

U.S. comics have an antecedent that is distinct from European comics: the earliest comic strips were found on the sports pages in daily newspapers, between reports on baseball, boxing, and horse racing. Indeed, the first comic strip, Mutt and Jeff (two men with a close relationship) debuted in 1907 as a strip that focused solely on Mutt, a racetrack gambler. This sports orientation set the tone for many later comics as a heterosexual male-dominated genre, both in the characters and situations depicted and in the industry behind the comics.

In the 1930s, however, comics could be quite playful about gender and sexual orientation. For example, the two main characters in George Herriman’s comic Krazy Kat, which ran from 1913 to 1944, are Krazy Kat and Ignatz Mouse. Krazy loves Ignatz, and what makes this relationship special is that other characters in the strip refer to Krazy by both male and female pronouns. Krazy at times wonders whether they should marry a man or a woman.

Comics could also be quite explicit, as seen in the Tijuana bibles, which were typically very cheap, eight-page brochure-type publications that satirized Hollywood stars and other popular figures, such as Archie from the comics, with situations that include hetero- and homosexual couples and threesomes and sometimes animals. The eight-pagers were extremely popular during the 1930s and paralleled the overt sexuality then common in films (e.g., the not-so-subtle innuendo of Mae West), which in turn led to the imposition of the Hays Code (1934–1968), an effort to censor movies.

Fans and scholars alike recognize the Golden Age of comics as comprising the years 1930 to 1956, a period that saw the introduction of popular superheroes. World War II, in particular, inspired the rise of Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, and many other superheroes. Also appearing in the 1940s and early 1950s were two other popular genres: crime comics, such as True Crime Stories, first published in 1947, and horror comics, such as Tales from the Crypt, which began in 1950. These two genres were rife with extreme violence and sexuality—a development that did not sit well with the conservative social backlash of the 1950s.

Censorship of American Comics

Into this cultural atmosphere came Fredric Wertham, a psychiatrist who had expressed disapproval of comics for years, including in a 1948 interview, “Horror in the Nursery,” and a symposium speech, “The Psychopathy of Comic Books.” In 1954, Wertham published his infamous book, Seduction of the Innocent: The Influence of Comic Books on Today’s Youth, which argued that comics, by depicting morally questionable acts and images, were a significant cause of juvenile delinquency. Wertham expressed concern regarding graphic violence, drug use, sexual imagery, and other topics. One of his major concerns, however, was what he considered to be implied homosexual content. He argued, among many other points on the subject, that Wonder Woman, an independent and physically and emotionally forceful woman, was implied to be lesbian; and that Batman and Robin, two bachelor males living together and emotionally close to each other, were implied to be gay.[57]

Wertham’s book led to hearings before the newly formed U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency in 1954. By the summer after the Senate hearings, fifteen comics publishers had gone out of business, and multiple city councils had passed ordinances banning crime and horror comics. The surviving publishers, in desperation, formed an organization known as the Comics Code Authority to police their own publications.

The Comics Code Authority wrote and enforced the Comics Code, which was based on the earlier Hays Code but had many far stricter regulations that prohibited anything considered remotely morally objectionable. The Comics Code covered graphic violence and sexual content but also had extensive mandates regarding acceptable story lines:

- It required, for instance, that “in every instance good shall triumph over evil.”

- It effectively banned entire genres.

- It disallowed “references to physical afflictions and deformities” (disabilities).

- It forbade the portrayal of racial prejudice, which was used to disallow the inclusion of any nonwhite central characters in what had previously been an unusually racially diverse medium.[58]

A primary focus of the Comics Code was sexual activity. Though the Hays Code had made generic statements about “sex perversion,” the Comics Code was more specific and verbose. It prohibited “sexual abnormalities,” “sadism,” “illicit sex relations,” and on and on. It required that any romantic stories emphasize the “sanctity of marriage”—a phrasing that may sound familiar today. And among the most forceful prohibitions was a mirror of the Hays Code: “Sex perversion or any inference [sic] to same is strictly forbidden.”[59]

Superhero comics were nearly the only genre able to adapt to the dozens of comprehensive rules, and other genres fell to the wayside. A large portion of publishers had already gone out of business and many more were unable to sustain readership while following the Comics Code. This left most comics, especially superhero comics, to only two publishers—National Comics, now known as DC Comics, and Atlas Comics, now known as Marvel Comics. The Comics Code led to and cemented the lasting image of superheroes as morally unassailable and superhero narratives as morally simplistic. And it removed nearly all diversity.

Underground Comix

The Comics Code devastated the comics industry—but not entirely. The 1960s and 1970s witnessed the rise of underground comics, many of which started in college newspapers and reflected the collegial culture of rebellion. One early example of underground comix, as they were called, is Zap, a series that Robert Crumb and other authors and artists introduced in 1968. The comics scholar Hillary Chute has identified this underground industry as very much a “boys’ club” that produced raunchy narratives with a strong white, male heteronormative focus on taboo subjects and gender and racial stereotypes.[60] Zap, for example, had the bisexual characters Captain Pissgums and his Pervert Pirates, who were kinky drug addicts.

Following are some highlights of underground comix that include LGBTQ+ characters:

- Matt Groening’s series Life in Hell, which began in the late 1970s and ran until 2012, featured Akbar and Jeff, who are gay anthropomorphized rabbits.

- In 1976, Garry Trudeau introduced the gay character Andy Lippincott to Doonesbury, which started in 1970 and is still running today; Andy died of AIDS in 1990.

- In response to the male-dominated comics of this period, a group of women organized to publish Wimmen’s Comix, a comics anthology that ran from 1972 to 1992. The first issue included a story with a lesbian main character, “Sandy Comes Out.”

- Howard Cruse was the editor of a similar comics anthology, Gay Comix, which ran from 1980 to 1998. Cruse also authored Wendel in 1986, which is the first queer comic strip with a gay author. His graphic memoir, Stuck Rubber Baby, relates his coming of age as a gay boy growing up in the South and his participation in the civil rights movement.[61]

- The comic book series Strangers in Paradise, by Terry Moore, ran successfully from 1993 to 2007. At the heart of this series, which often took a turn toward mystery and intrigue, was a romantic triangle between two women, one of whom identifies as lesbian, and the man who meets them.

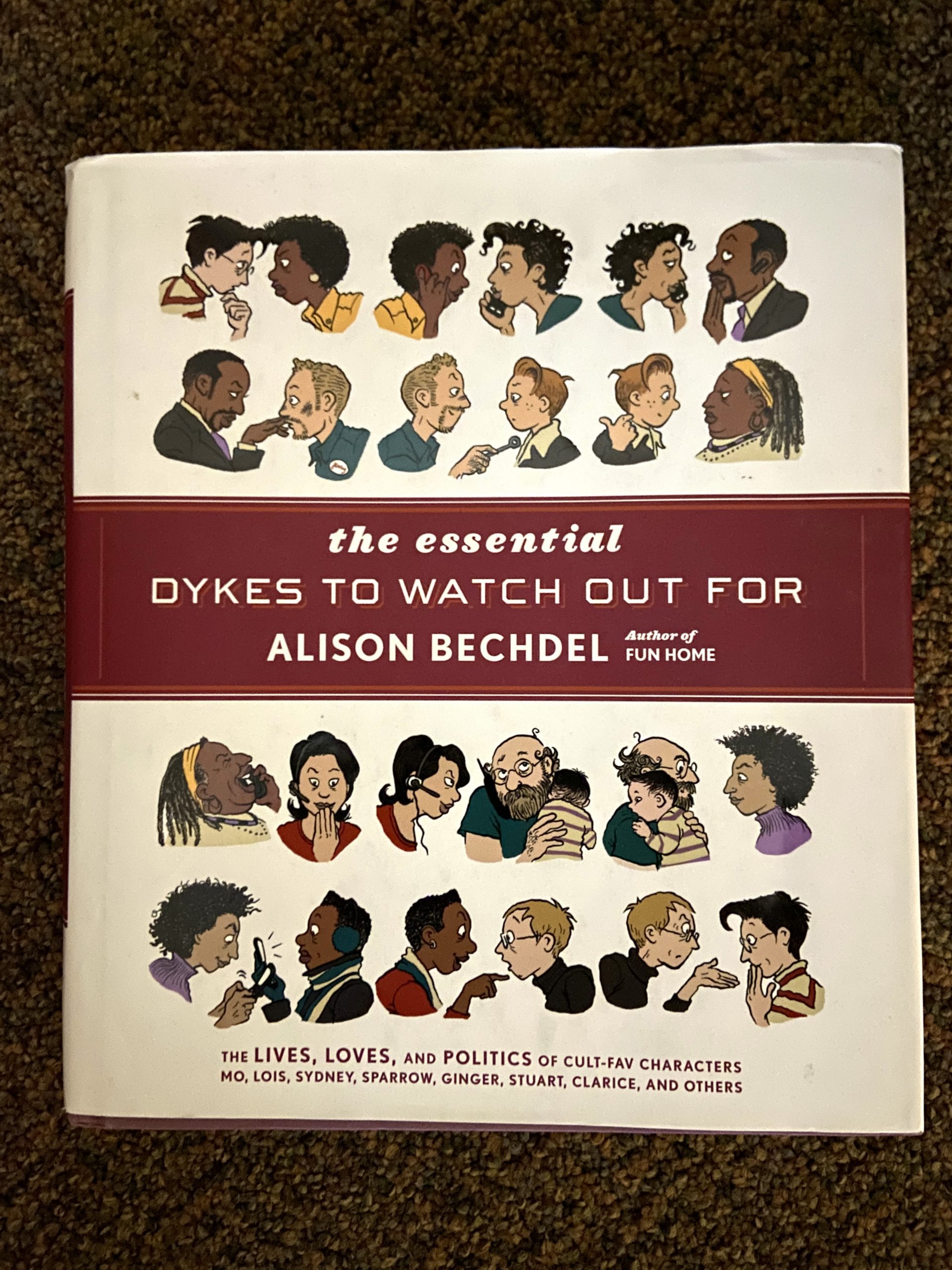

- The comic strip Dykes to Watch Out For by Alison Bechdel ran from 1983 to 2008 (figure 11.14). The strip follows a group of lesbians in real time through personal and political struggles, starting with the Ronald Reagan years and young love and continuing through graduate school, parenting, falling in and out of love, and finally the election of Donald Trump.

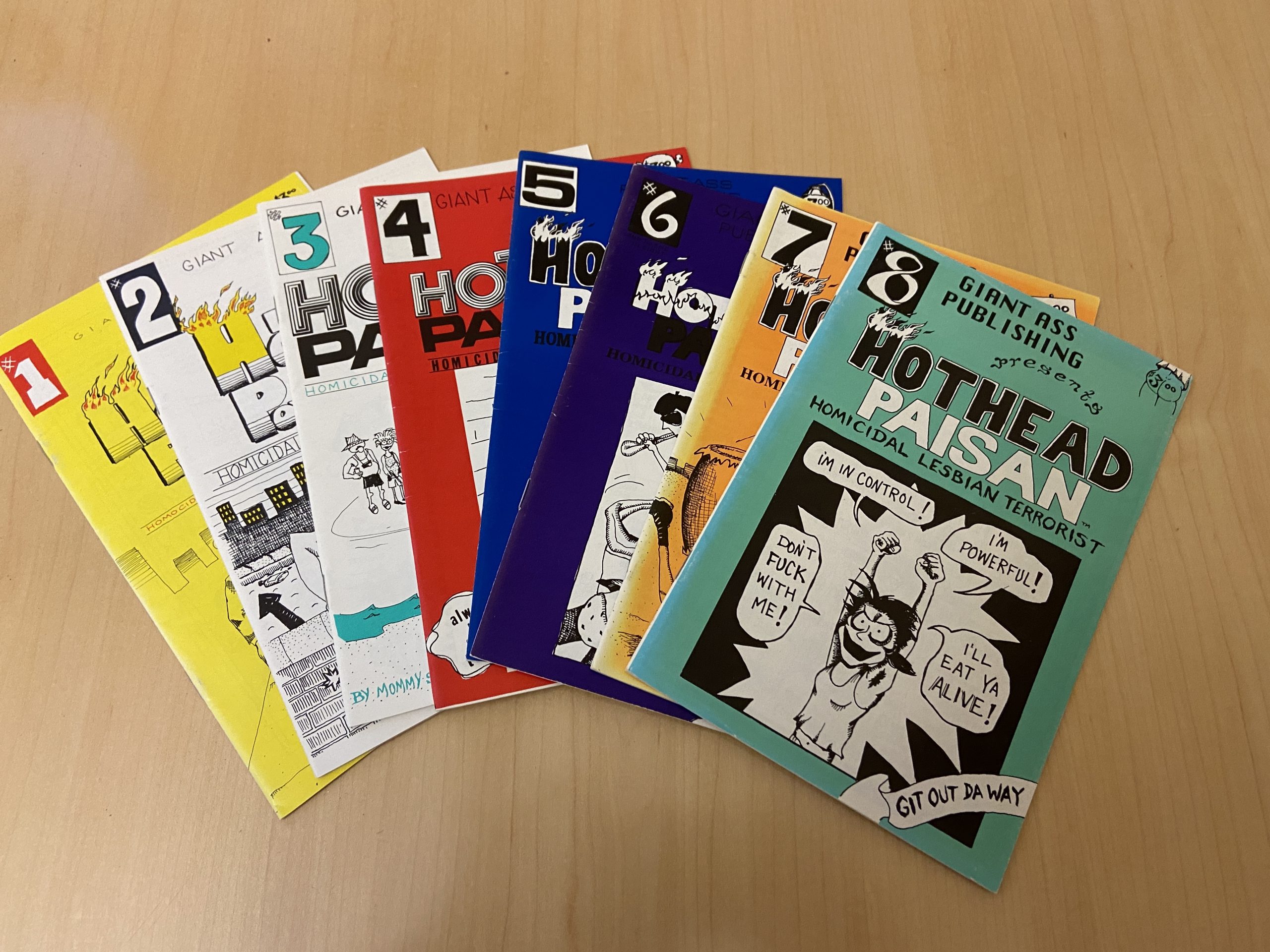

- My personal favorite, Hothead Paisan: Homicidal Lesbian Terrorist, was initially self-published in 1991 by Diane DiMassa (figure 11.15). Hothead rages against a sexist society by castrating men. The comic series ran until 1998.

- Roberta Gregory’s comic book series Naughty Bits ran from 1991 to 2004, and her comics starred Midge McCracken, or Bitchy Bitch, and Bitchy Butch, the “angriest dyke in the world.”

One important landmark publication almost single-handedly changed the comics industry. Art Spiegelman’s Maus, which was published serially in Raw magazine from 1980 to 1991, demonstrated that the genre could maintain a high artistic quality and deal with substantive issues.

The alternative and independent comics that emerged from the underground comix in the 1990s and early 2000s built on this newly found status, and notable publications that depicted lesbian characters are Alison Bechdel’s graphic memoir Fun Home (2006) and Shannon Watters’s comic book series Lumberjanes. The latter series started in 2014 and relates the adventures of five girls at Miss Qiunzella Thiskwin Penniquiqul Thistle Crumpet’s Camp for Hardcore Lady Types, an all-girls’ camp with activities that encourage transgressive gender roles.

Reintroducing LGBTQ+ Characters in Mainstream Comics

Over decades, authors, artists, and publishers had gradually chipped away at the code, but LGBTQ+ characters were among the last major frontiers. Asexual characters can be counted on one hand; transgender characters on two. Most LGBTQ+ characters have been introduced using various tactics to soften their impact, to make them less shocking and more palatable. Acceptance of LGBTQ+ people and issues in society, as a whole, has been a major factor enabling progress. Inclusion has filtered in toward the center from the outside—into first creator-owned comics, then smaller publishers, then the adult-oriented publications of large publishers, and finally the center of the mainstream.

Here follows a short time line of the inclusion of LGBTQ+ characters in superhero comics, showing those shifts.

- 1988: The first gay character, Extraño, appeared in Millennium no. 2; he was not technically out but was an intensely queer-coded caricature.

- 1991: The reformed villain Pied Piper came out as gay in The Flash no. 53.

- 1992: The first explicitly gay hero, Northstar, came out in Alpha Flight no. 106. The creator, John Byrne, had supposedly intended for him to be gay since his debut in 1979 but had been repeatedly overridden by editors.

- 1992: One of the first multisexual heroes, Element Lad, entered a similar-gender relationship in Legion of Superheroes no. 31, a soap opera–esque comic. This character was later retroactively written out as having never happened.

- 1993: A bisexual transgender woman, Coagula, briefly appeared starting in Doom Patrol no. 70 under an adult-oriented DC Comics imprint. She was created by Rachel Pollack, a transgender writer.

- 1994: A transgender man, Masquerade, was outed in Blood Syndicate no. 10 under another adult-oriented DC Comics imprint. He was a shapeshifter who used his ability to present as male but had dialogue that made clear his identity as a transitioned man.

- 1999: Apollo and Midnighter, written as parallels to Superman and Batman, became a couple in The Authority no. 8, under yet another adult-oriented DC Comics imprint.

- 2002: Apollo and Midnighter became the first married gay couple in superhero comics in The Authority no. 29.

- 2005: Billy Kaplan and Teddy Altman, a gay teenage couple, were introduced as main characters in Young Avengers no. 1, though this was not initially explicit, and they would not explicitly kiss until 2012.

- 2006: The first major lesbian hero, Batwoman, debuted in New 52, volume 1, no. 7.

- 2011: DC Comics and Archie Comics officially abandoned the Comics Code, the last major publishers to do so.

- 2012: A nonbinary character, Sir Ystin, came out in Demon Knights no. 14 after a year of their gender ambiguity being used as a running gag.

- 2012: Shortly after New York legalized same-sex marriage, Northstar had the first same-sex wedding in mainstream comics in Astonishing X-Men no. 51.

- 2014: Loki said he identifies as both a man and a woman in Loki: Agent of Asgard no. 2. This makes him arguably the highest-profile transgender character not only in comics but also in all of U.S. popular culture, but very few people are aware that he is transgender.

- 2016: Apollo and Midnighter became the first gay couple to headline a comic with the six-issue miniseries Apollo and Midnighter.

- 2016: Jughead, a character in Archie Comics, came out as asexual in Jughead no. 4.

- 2016: Wonder Woman was stated to be bisexual by a writer, although the references to this in the comics themselves are subtle and easily missed or denied.

- 2017: Loki used the word genderfluid to describe himself for the first time in Unbeatable Squirrel Girl no. 27.

Tropes and Themes

LGBTQ+ characters in comics show many of the same tropes as in other media—some negative, some neutral, some maybe even positive. However, some tropes appear with particular frequency in comics, as opposed to other media. These are often employed to make the characters less visibly gay, thus less likely to be forbidden by the Comics Code Authority (in earlier years) and easier on the slow-changing, image-concerned industry both earlier and later. A very abbreviated list of a few of them follows.

- Explicit Naming: Several characters are stated to be LGBTQ+ by writers or editors, but the actual text contains only ambiguous hints toward their identity. This allows the characters to technically be LGBTQ+ without the average reader being aware of it. This is particularly common with high-profile characters such as Deadpool and Wonder Woman.

- Nonbinary Shapeshifters: Nearly all transgender characters in fiction are inhuman, and comics are no exception. Comics, though, are unusually fond of the nonbinary shapeshifter, who shifts between genders and simultaneously physically between sexes. Thus at any given point, the reader is able to think of the character as cisgender and doesn’t have to deal with a character’s identity not “matching” their body. (And neither do the people in charge.) Examples include Loki, Mystique, and Xavin.

- It’s Not Gay If It’s an Alternate Universe: This trope, nearly unique to comics, depends on comics’ use of the multiverse. Characters are often portrayed as LGBTQ+ in alternate universes, allowing both companies and audiences to deny that any queerness exists in the primary versions of those characters. The trope is ridiculously common, applying to dozens of characters. DC Bombshells is particularly notable. Bombshells is an alternate universe with its own yearslong series in which nearly the entire cast (composed of alternate versions of preexisting characters) is lesbian, bisexual, transgender, or some combination. A variant of the trope makes a character a different gender so that a pair can be together without being LGBTQ+ at all. Dark Reign: Fantastic Four no. 2 shows an alternate universe in which Captain America and Iron Man are married—and Iron Man is a woman. In other narratives, characters in alternate universes with the same roles and titles but different names are LGBTQ+.

- But Not Too Gay: This occurs across media, but because the Comics Code emphasizes visuals, it is particularly significant in comics. LGBTQ+ characters are desexualized compared with their straight counterparts. Queer couples are often together for years without so much as an on-page kiss, whereas straight couples in the same series are shown in blatantly explicit situations. Queer couples may even be restricted from having any physical contact at all.

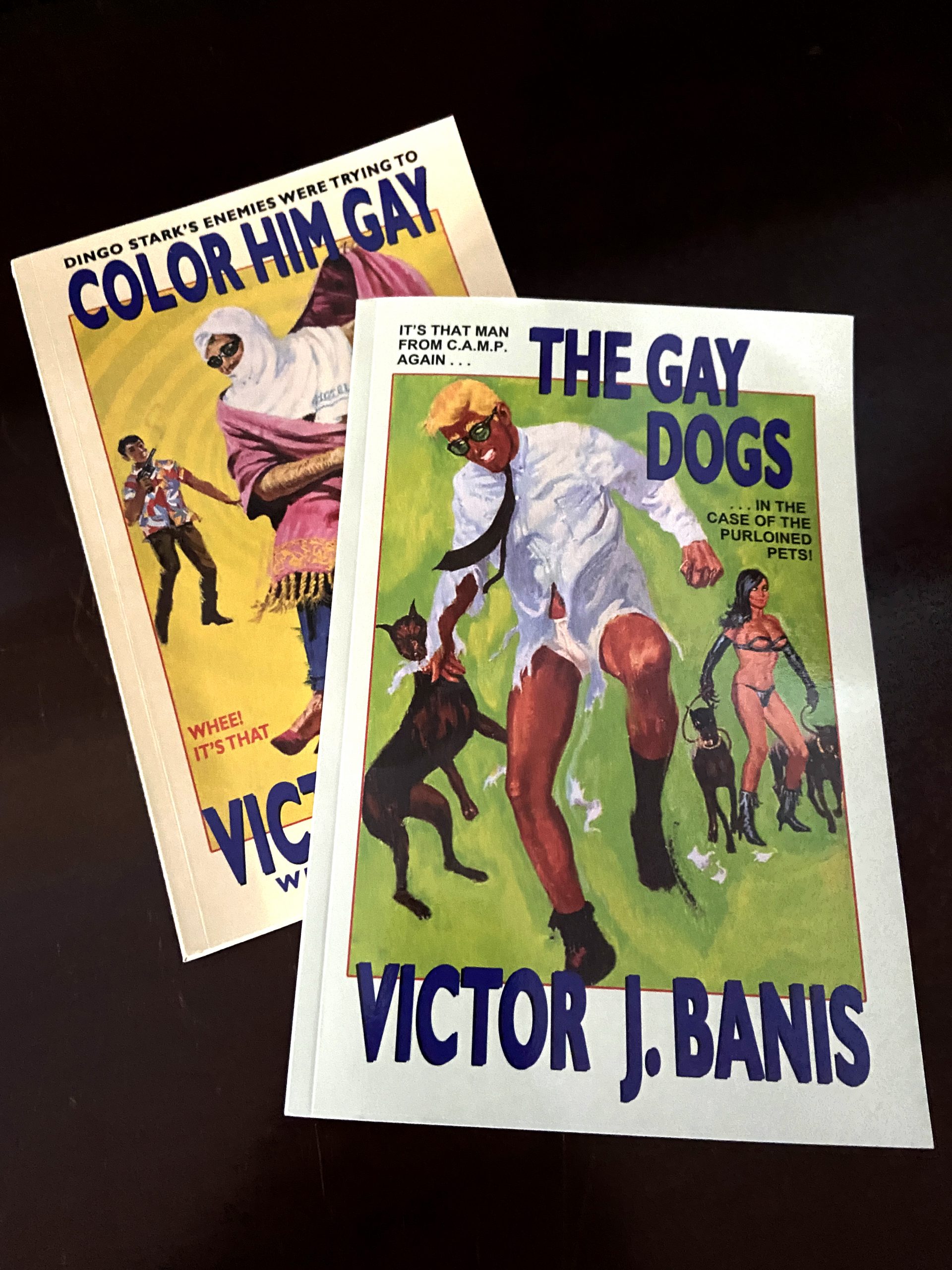

Lesbian and Gay Pulp Fiction

Cathy Corder

Many people dismiss pulp fiction as cheap, trashy paperbacks that lower-class people read in lieu of literary classics. Yet because they could be produced and distributed so quickly and inexpensively, these stories were able to respond with immediacy to the great changes in society that followed World War II. Sandwiched between the Kinsey reports on male and female sexual behavior (1948 and 1953) and landmark censorship trials and the 1969 Stonewall rebellion, the characters and narratives of lesbian and gay pulp fiction reflected a more open attitude toward sexual identities and relationships but also the harsh reality during the McCarthy era of the lavender scare and the moral panics about homosexuality that were used to justify firing homosexuals from government positions. Pulp fiction that features LGBTQ+ characters as the primary protagonists was a genre roughly from 1945 to 1970. These books were usually printed under a pseudonym, and scholars and archivists have been uncovering the real authors, many of whom identify as gay or lesbian. Further, printing houses with LGBTQ+ owners or sponsors enabled the widespread dissemination of these popular stories. Much pulp fiction from the 1950s and 1960s was reprinted starting in the 1980s by, for example, Naiad Press, Cleis Press, and Argo Press.

Historical Context for Pulp Fiction

The antecedents for pulp fiction go back to the nineteenth century, when the rise of industrialization led to both more economical printing processes and more spare time for reading among the middle and working classes. The penny press was tabloid-style newspapers that included fiction along with news, and because these were so cheaply printed, readers thought nothing of discarding them with the trash.

This early popular literature was quite melodramatic and highly moralistic, but that quality evolved into the more sensational fiction that featured sex, sexual crime including rape and incest, crime more generally, family secrets, squalor, and clear-cut differences between good and evil. One early type of this popular fiction, the city mystery, brought together characters from all classes, races, and genders through convoluted plots that focused on the decadence of the upper class and the vile nature of the lower.

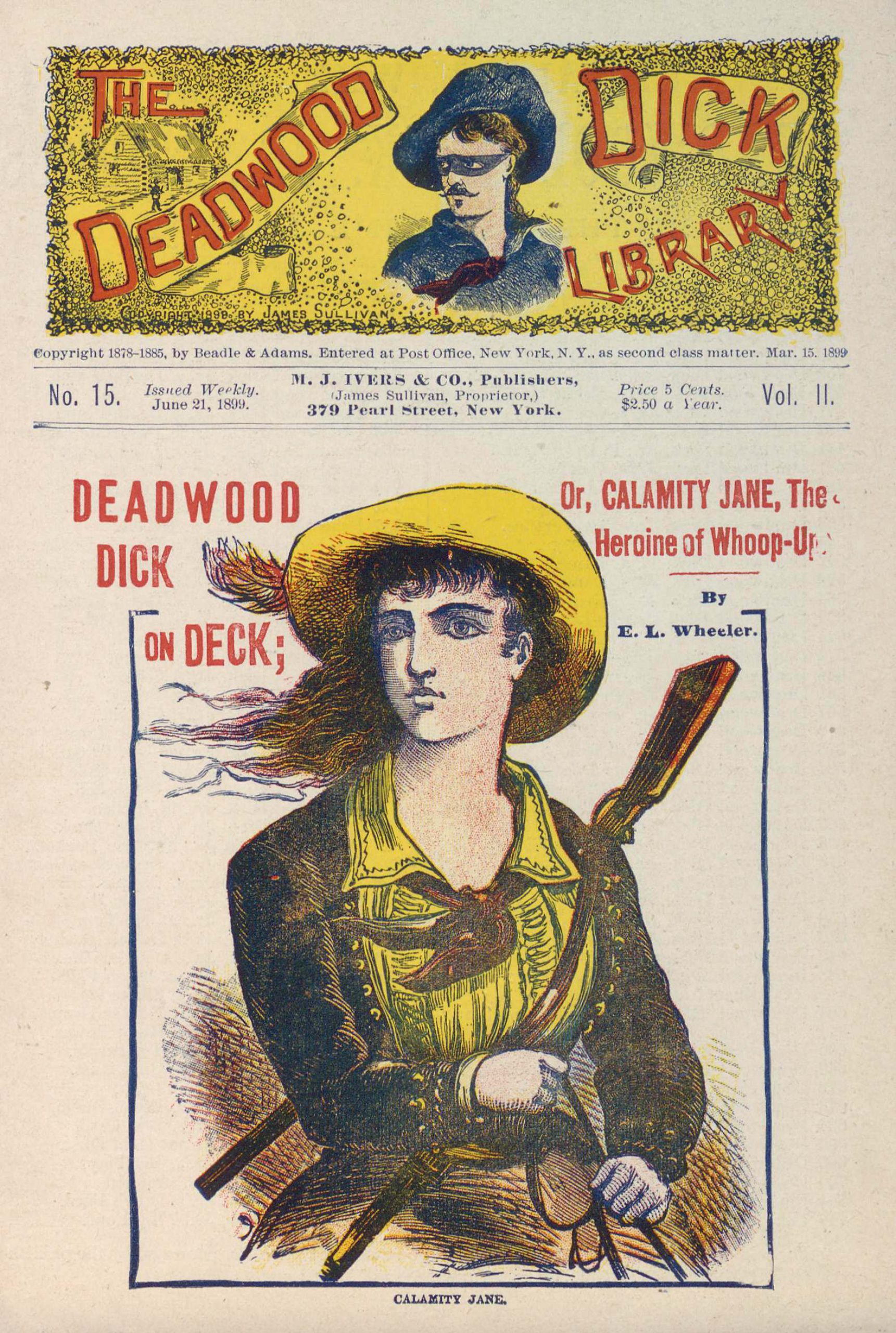

Other genres included westerns (such as the Deadwood Dick series; figure 11.16), horror (derived from the earlier Gothic genre), and crime and police stories. Although none of this literature can be identified as LGBTQ+, it had important features that shaped the queer pulp of the twentieth century. One such feature was the garish covers that quickly identified the type of story they contained.

Another important characteristic, found particularly in the city mystery, was the manner in which these narratives identified specific urban spaces where certain communities of people might congregate. Almost every city mystery features secret passages, hidden doors, and shadowed alleys—all suggesting the dark underworld where social mores could be transgressed. (It is no wonder that twilight becomes such a catchword in queer pulp.) One of the best contributions of lesbian and gay pulp fiction was to help LGBTQ+ people see that they could be a part of their city and that there were spaces that would welcome them.

Again, although there were no LGBTQ+ characters in early pulp, there were gay subtexts that highlight effete men who wear suffocating perfumes and too much hair oil and voracious women who threaten young virgins. Much popular fiction of the nineteenth century provided the vocabulary and stereotypical characters for later reading audiences concerning individuals who fail to conform to proper social and sexual guidelines.

Pulp Fiction in the Twentieth Century

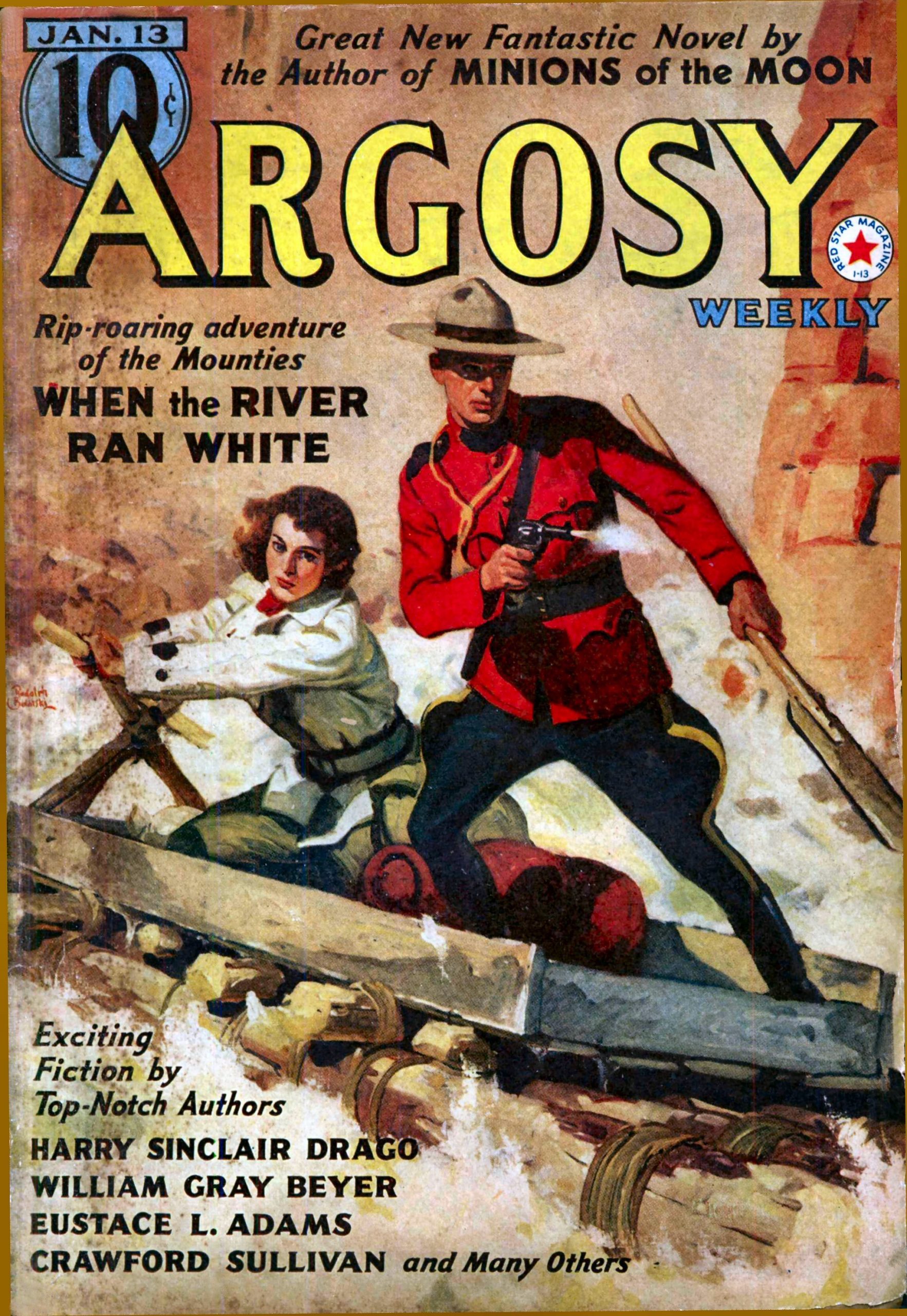

The 1920s and 1930s saw the continuing publication of popular stories in magazine format, and these mass-marketed magazines began to specialize in specific sorts of stories: crime, passion, adventure, romance, and science fiction. These stories continued to feature garish covers and sensational language (figure 11.17).

Then, in 1939, Simon and Schuster Publishers established a new division, Pocket Books, which was modeled after Penguin Books in England. With the introduction of a much cheaper form of paper production based on wood pulp (hence the genre’s name), Pocket Books was able to sell these new paperbacks for twenty-five cents. At first, Pocket Books reprinted literary classics in this new format, which shared characteristics of the earlier magazines. Every author from Shakespeare to William Faulkner could be pulped into a cheaper edition, and lurid cover art and text were part of the process.

By the advent of World War II, pulp fiction magazines were popular and profitable—but they were also considered second-rate literature. With wartime paper shortages, magazines soon died out, but publishers made good use of digest and magazine presses to produce Armed Services Editions from 1943 to 1947. These small fiction and nonfiction paperbacks were issued to members of the military and introduced new generations of readers to entertaining and distracting stories printed in a portable format.

Postwar publishing houses responded to these new readers with an explosion of cheap paperbacks. Fawcett’s Gold Medal Books, established in 1950, was the first to publish original writing in this format, typically five by seven inches, with a glued spine, garish cover art, and cheap, rough paper that quickly turned yellow and disintegrated.

Lesbian Pulp Fiction

In 1950, Gold Medal Books printed the first lesbian pulp novel: Women’s Barracks by Tereska Torrès. This novel is a largely autobiographical account of the time that the author spent in London at a military barracks for women serving in the Free French Forces. Torrès herself narrates, relating the day-to-day life for a group of five French women, who differ in age and in experience and who couple and partner in various ways. One of the first scenes of the story occurs when the women have stripped naked for their medical evaluation; much focus is put on the individual female bodies, both naked and clothed. And one of the characters, of course, commits suicide.[62]

Appearing soon after Women’s Barracks were Vin Packer’s Spring Fire (1952), considered the first lesbian pulp fiction by a lesbian author, and Patricia Highsmith’s The Price of Salt (1952), written under the name Claire Morgan. The Price of Salt was unusual for its time, in that the two protagonists remain together at the end of the story; at the end of Spring Fire, one woman is confined to a mental hospital because of her unfortunate alliances.[63]

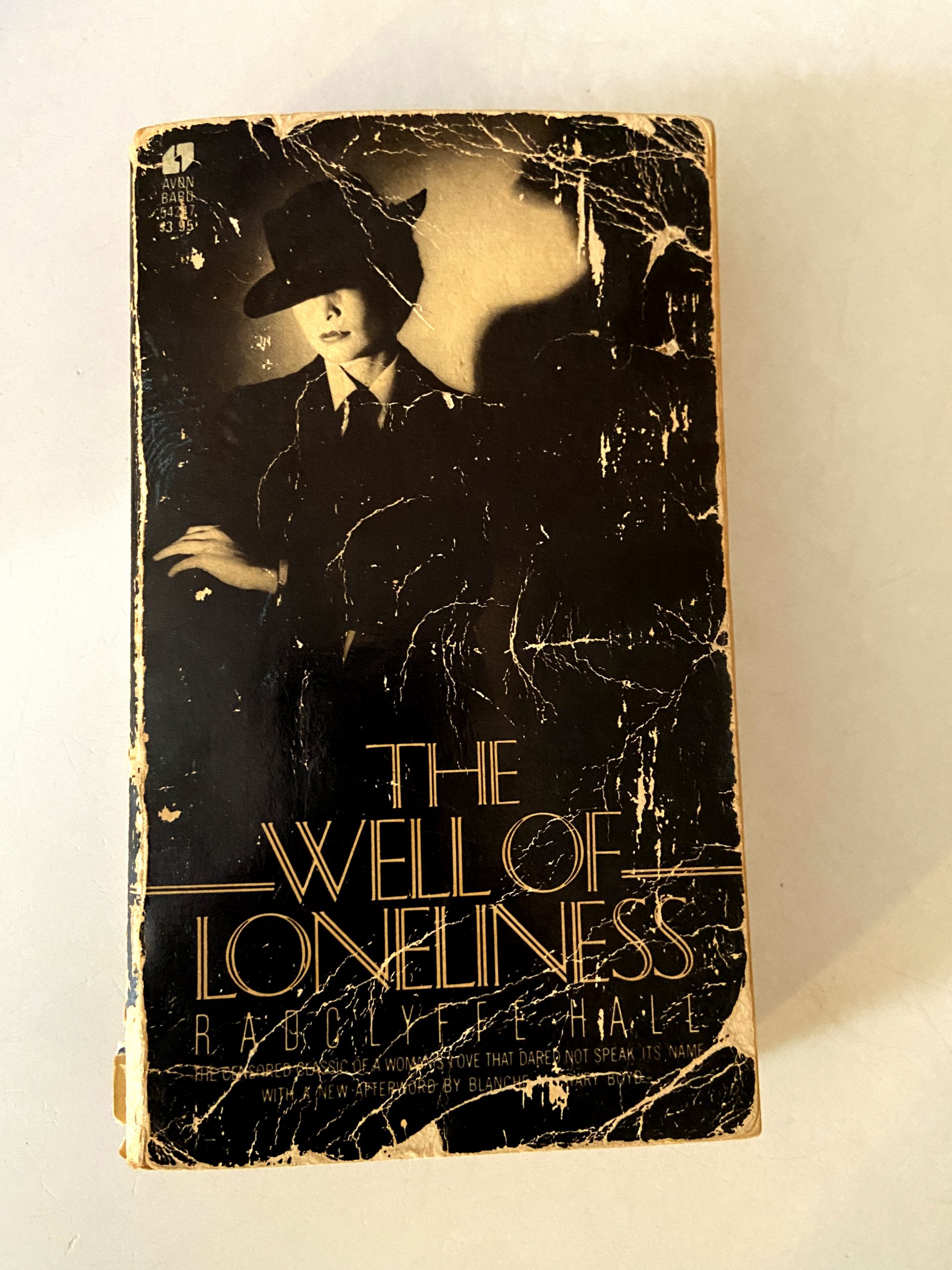

Lesbian pulps were not the first appearance of lesbian women in literature. Earlier in the century, Radclyffe Hall wrote The Well of Loneliness (1928) with the “inverted” character Stephen Gordon. Djuna Barnes published Night Watch in 1936 with the help of a literary agent, and Gale Wilhelm published We Too Are Drifting in 1935 with Random House. Although these early works are now considered classics of lesbian literature, even Radclyffe Hall could be pulped and reissued in the 1950s (figure 11.18).[64]

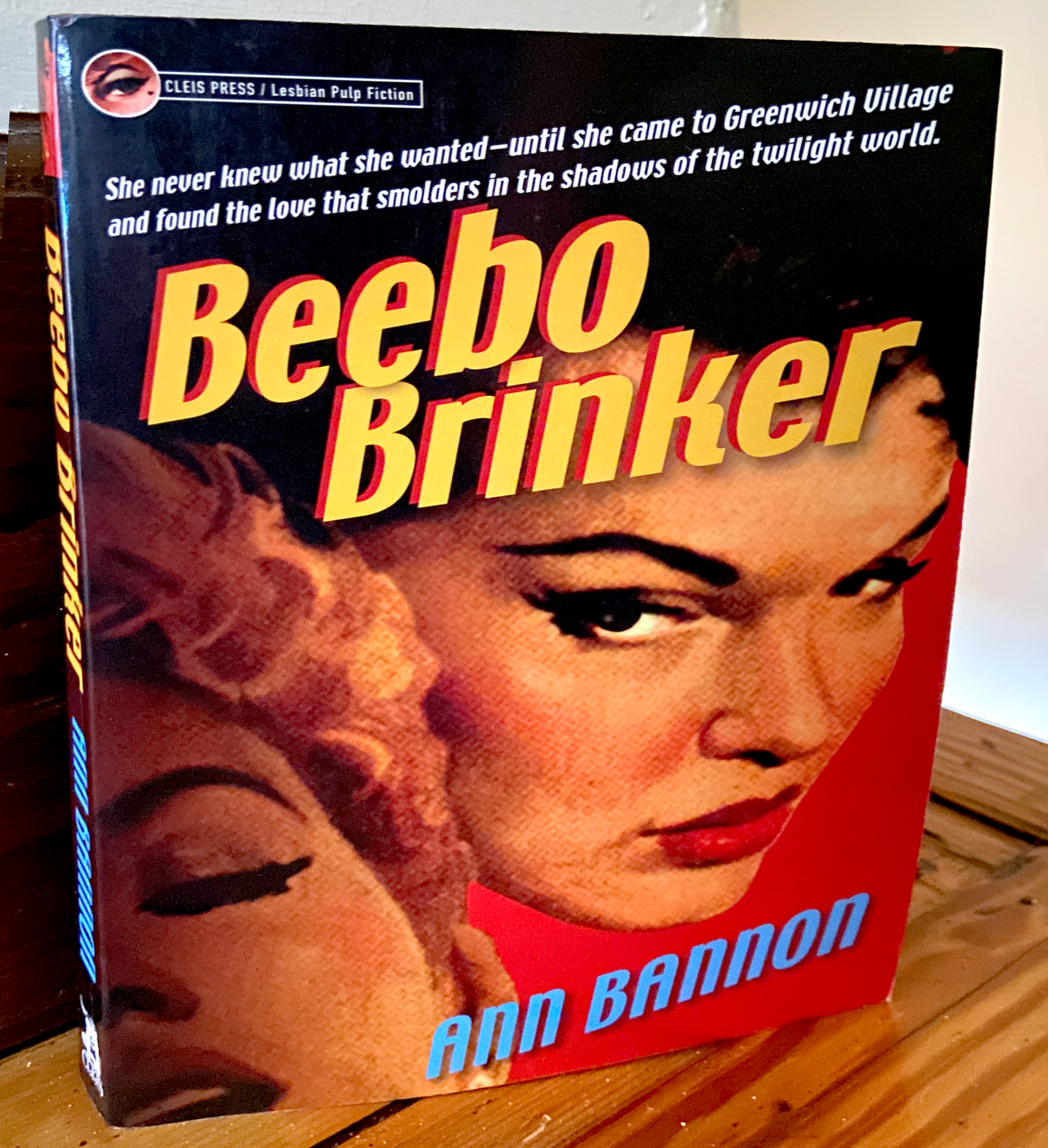

Although the earlier lesbian pulp fiction, such as Women’s Barracks and Spring Fire, ended tragically in suicide or insanity, a handful of lesbian authors contributed a great deal to the increasing level of self-acceptance among their readers, due to their complex characterizations and positive plot resolutions. Across the nation, lesbians read pulp fiction and learned that they were not alone, and lesbian pulps did much to help these readers establish their own communities. Ann Bannon, whom many consider the queen of lesbian pulps, wrote five books in the Beebo Brinker series (1957–1962) (figure 11.19). Her characters range from the mannish Beebo to more femme characters, demonstrating how far pulps could move from the stereotypical people who transgressed social and sexual norms.[65]