Private: Part V: Relationships, Families, and Youth

Chapter 8: LGBTQ+ Relationships and Families

Sarah R. Young and Sean G. Massey

Introduction

This chapter provides an overview of research and practice relating to LGBTQ+ families, relationships, and parenting. It describes the definitions LGBTQ+ people have for family and the relationships LGBTQ+ individuals have with their families of origin. It investigates how minority stress, family acceptance, and rejection affect these relationships. The chapter discusses how LGBTQ+ people form intimate relationships, how people in these relationships navigate established (often discriminatory) social and legal systems, and how recent social and legal changes (e.g., marriage equality) affect these relationships. It talks about the nature and prevalence of families headed by LGBTQ+ people that include children and the ways that LGBTQ+ people become parents. It reviews the changing legal landscape as it relates to same-sex parenting and family building and delineates some of the challenges these families face when interacting with legal systems, health care and human services providers, and educators. The final section considers what it means to come out as LGBTQ+ to one’s children. Each section also critically explores the relevant scientific literatures, challenges existing anti-LGBTQ+ myths, and identifies resources and organizations that support LGBTQ+ families.

It is difficult to quantify how many people in the United States are in LGBTQ+ relationships. U.S. census data give us some idea, although the numbers are likely underreported. The U.S. census counted approximately 10.7 million adults (4.3 percent of the U.S. adult population) who identify as LGBTQ+ and 1.4 million adults (0.6 percent of the U.S. adult population) who identify as transgender. Of those, approximately 1.1 million are in same-sex marriages (totaling 547,000 couples),[1] and 1.2 million are part of an unmarried same-sex relationship (totaling 600,000 couples).[2]

What Is a Relationship?

The word relationship can refer to many types of social interactions. Relationship research typically focuses on interpersonal relationships, which are deep, close relationships between two or more people. These relationships are sometimes described in other ways, as a friendship, a couple, or a marriage. Research exploring LGBTQ+ interpersonal relationships is often centered on intimate or sexual relationships that are described as a partnership, a couple, a marriage, or just a relationship.

How Do LGBTQ+ Relationships Form?

Relationships vary in the internal and external resources that strengthen the relationship, contributing to the well-being of the members in the relationship, and that help them cope with the stressors they have to confront both as individuals and as a couple. The availability of external resources is a changing landscape for same-sex couples.[3]

For example, research has demonstrated that gay men, lesbians, and middle-aged heterosexuals—those looking for mates in what they term “a thin market”—are more likely to rely on the internet to find a partner.[4] A nationally representative longitudinal survey, “How Couples Meet and Stay Together (HCMST),” of over four thousand adults found that, on average, although heterosexual and same-sex couples reported meeting primarily through friends, trends since 2009 suggest that the number of couples meeting online from both groups is increasing, but same-sex couples are significantly more likely to meet online than heterosexual couples.[5]

Queer Resistance

Some same-sex relationships, with or without children, follow the expected norms regarding monogamy and exclusivity. Some relationships “queer,” or stray from, traditional heteronormative relationship norms, to include polyamorous relationships (three or more committed partners), multiparent families (often two women partners raising children with a male platonic friend who is the biological father), or platonic partnering (often a queer man and woman who are friends and partner to raise a child).[6] Queering these relationships can certainly lead to burdens, including negative judgment and discrimination from external sources. On the other hand, they can also bring strengths, including freedom, creativity, and a family or relationship that is tailor-made to the people involved (figure 8.1).

A study of a thousand gay men in Britain found that approximately 40 percent were or had been in an open relationship. In a study of gay male couples in the San Francisco Bay Area, agreements guiding open relationships varied considerably among gay male couples, with most having rules or conditions regarding extrarelational sex. A related study found that about equal numbers reported having agreements to allow sex with people outside the relationship (47 percent) and agreements to be monogamous (45 percent), with some (8 percent) reporting disagreements. Other studies have found slightly higher levels of monogamy (52.8 percent) and fewer couples reporting open relationships (13.0 percent), and some find “monogamish” relationships (14.9 percent) or discrepant relationships (in which partners do not agree on whether they are in an open or monogamous relationship; 19.3 percent). One study reported even higher rates of agreement to be monogamous (74 percent).[7]

Interestingly, most people maintain a strong bias in favor of monogamous relationships, viewing them more favorably than consensual nonmonogamous relationships in terms of their potential for providing relationship and sexual satisfaction. Monogamous relationships are also seen as more likely to preserve sexual health. However, little evidence exists to support these views. Most couples have little assurance that their partners remain faithful forever, and there is little evidence that nonmonogamists are less likely to practice safer sex. These widespread biases reflect negative media representations and the views of mental health providers and politicians.[8]

The AIDS epidemic fueled the study of sex among men who have sex with men, but there are significantly fewer studies of the sexual agreements of lesbian and bisexual female couples. “The Ultimate Lesbian Sex Survey,” conducted by the online magazine Autostraddle, asked “lady-types who sleep with lady-types” about their relationship agreements. Of the over 8,500 people who completed the survey, 56 percent reported being in a monogamous relationship, 15 percent in a nonmonogamous relationship, and 29 percent reported not being in a relationship. When asked about their preferred type of relationship, 62 percent said monogamy, 22 percent said mostly monogamy, 6 percent said open relationship, 5 percent polyamory, and the rest a range of other configurations, such as “triad,” “polyfidelity,” and “don’t ask, don’t tell.”[9]

Relationship Quality

The field of relationship studies is an interdisciplinary field that includes but is not limited to psychology, social psychology, social work, and marriage and family therapy. Before 2015 this field was not uniformly open to the study of same-sex couples, but it now is an important site of inquiry about LGBTQ+ relationship quality, longevity, and impact. Much of the literature on same-sex relationship quality focuses on comparing LGBTQ+ people’s dating, cohabitation, and marriage pathways and experiences with heterosexual people. This work has repeatedly found that LGBTQ+ relationships experience the same level of satisfaction compared with non-LGBTQ+ relationships and that similar variables predict stability and overall satisfaction in these relationships.[10] The outcome of this research has shown repeatedly that LGBTQ+ relationships are just as well adjusted as their heterosexual counterparts and experience similar stressors.

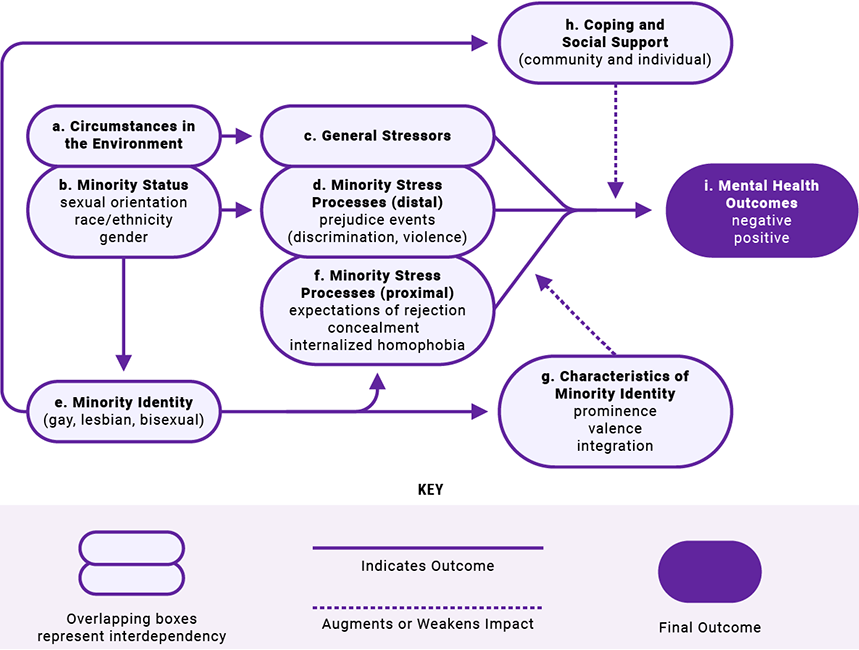

However, LGBTQ+ people, as stigmatized minorities, experience higher rates of mental and physical health challenges, such as mood and anxiety disorders, compared with heterosexual and cisgender people.[11] This unique stress, called minority stress, affects those in LGBTQ+ relationships both internally (internalized heterosexism) and externally (experiences of discrimination) and has a negative effect on relationship quality and satisfaction (figure 8.3). One way to explain the connection is that internalized stigma increases the likelihood for experiencing depression, and depression produces stress on a relationship.[12] In one sample of 142 gay men, trust in relationships was influenced by experiences of discrimination when measuring overall relationship satisfaction. In this same sample, those with lower internalized heterosexism had a greater sense of commitment and higher levels of relationship satisfaction.[13]

This stress provides unique challenges for LGBTQ+ couples and families, compared with their straight and cisgender counterparts. LGBTQ+ couples often have to navigate judgment and rejection from their families of origin and in systems, including employment and faith communities. As mentioned earlier, nonheteronormative couples (e.g., polyamorous LGBTQ+ couples) may face even more relationship scrutiny from others, although the impact of such scrutiny remains underexplored in the research.

Additional factors that affect heterosexual and cisgender relationships also affect LGBTQ+ relationships, including dating violence and divorce. Prevalence of dating violence among LGBTQ+ adolescents, although not as robust a line of inquiry as for heterosexual youth and adults, is higher than national averages for all adolescents. In addition, dating violence in adolescence appears to predict its perpetuation into college years, as well as other behaviors (such as not using condoms) that put these youth at risk as they enter adulthood. Thus the recognition and prevention of relationship and dating violence with LGBTQ+ communities is important. Some researchers and practitioners theorize that the lack of consistent and positive role models and inclusion of healthy LGBTQ+ relationships in sex education curricula and from parents and mentors creates a vacuum of information on negotiating healthy relationships, particularly for adolescents.[14] Thus, one way to improve relationship quality for LGBTQ+ couples and families is to ensure an inclusive curriculum and access to information that includes queer couples and families across the lifespan.

Those who enter the normative relationship of legal marriage may later opt to seek a legal divorce. Although the process of initiating a divorce has become a fairly equal process between same-sex and different-sex couples, rates of divorce may be different. In several studies in the United Kingdom, lesbians were twice as likely to seek a divorce compared with gay men. In reporting on these statistics, one sociologist theorized that higher rates of divorce among queer and lesbian women can be explained by women entering commitment sooner and having higher standards for the relationship overall.[15]

What Is a Family?

For some, family refers specifically to a social unit of two people, most often a man and a woman, who live together, share resources, and are raising children (or plan to reproduce and raise children) (figure 8.4). However, family actually describes many types of social organizations. It can refer to groups of people organized by kinship and biology—with designations like parents, siblings, cousins, and aunts or uncles—as well as those, regardless of kinship, who live together, share resources, or care for each other.[16] Nuclear family, single-parent family, extended family, family of choice, and blended family are terms used to describe different types of families. Indeed, the effort to understand the meaning and function of family is a central goal of many of the social sciences.

Families serve varied functions, including reproducing and providing for children, regulating sexuality and gender by communicating and reinforcing social norms, and transmitting cultural knowledge. However, the particular functions and purpose of family also vary across cultures and can change over time. For example, the Western notion of family changed significantly as populations moved from farm- and household-based economies to industrial factories and into cities. Whereas farming relied on the family to create the labor necessary for maintenance of land, the production of necessary goods, and ultimately the survival of its collective members, the family in the cities that blossomed under industrial capitalism became a more affective or intimate relational unit that can also serve as a source of individual happiness.[17]

Heteronormativity in Families

Like heterosexual relationships, same-sex relationships form within the culturally defined social norms that organize sexuality and pair bonding in a society in a particular historical context. Modern same-sex relationships, however, exist within a heteronormative context that privileges heterosexual relationships, organizes gender-role expectations in a way that reinforces those expectations, and marginalizes nonheterosexual desire, love, and pair bonding. Additionally, heteronormativity also reinforces the ideal (although not always the practice) of sexual and romantic monogamy, links family authenticity with the presence of children, and implies the need to adhere to patriarchal ideals for the division of domestic labor, sex roles, and often even the vows and covenants made between partners.

What Are LGBTQ+ Families?

These contested definitions of family vary considerably across time and cultural context but have always influenced understanding of LGBTQ+ families (figure 8.5).[18] Researchers investigating the definitions of family for people in the United States found that definitions included a broad range of understandings. They describe an inclusionary model, defining family quite broadly as “same-sex and hetero-sexual couples with or without children, regardless of marital status.” A moderate model defines family as “all households with children, including same-sex households.” Finally is the exclusionary view, defining family as a “heterosexual married couple with children.”[19] Other important aspects of family are the functional characteristics it serves, such as relationship quality, commitment, care, love, or in the case of inclusionists, “whatever it means to them.”[20]

Research has also explored the boundaries of family, proposing the idea of “fictive” and “voluntary” kin.[21] Chosen families are defined as “non-blood related friends who [exist] somewhere between the realm of friends and kin . . . [who] perform a surrogate role, often filling in for family members who are missing due to distance, abandonment or death.”[22] It has been suggested that chosen families are more common among marginalized groups.[23] However, use of the term chosen family may vary by class and race. White middle-class LGBTQ+ people are more likely to use the term, and lower-income LGBTQ+ people of color are less likely to use it but also less likely to use exclusionary definitions of family in general.[24]

Family Support and Rejection

Family support and acceptance is an important psychological resource that can influence an individual’s well-being in a number of ways (figure 8.6). It improves one’s sense of self-worth, increasing optimism and positive affect.[25] Unfortunately, supportive and nurturing family is not the reality for all LGBTQ+ people. Most families exist within a social context defined by heterosexism and anti-LGBTQ+ prejudice. Some families are able to resist heterosexism and embrace LGBTQ+ family members, and some, although initially challenged by the idea that a family member is LGBTQ+, are able to resist or overcome their prejudices and accept those LGBTQ+ members. For others, heterosexism and anti-LGBTQ+ prejudice are too pernicious and may manifest as hostility, rejection, and even violence.

Family Stressors

Rejection by family members of one’s sexual orientation, gender identity, or gender expression can affect the health and wellness of people who identify as LGBTQ+. According to Dr. Caitlyn Ryan at the Family Acceptance Project, this rejection can include violence like “hitting, slapping, or physically hurting the youth because of his or her LGBT identity,” “excluding LGBT youth from family events and family activities,” and “pressuring the youth to be more (or less) masculine or feminine.”[26] LGBTQ+ people whose families reject their sexual orientation, gender identity, or gender expression have higher rates of suicide across their lifetime, higher rates of depression, and greater risk of HIV infection compared with those who report higher levels of acceptance by their families.[27]

Family Buffers

Family acceptance lessens some aspects of LGBTQ+ minority stress—such as the distress and negative feelings that may be associated with sexual orientation. LGBTQ+ youth with accepting families report greater acceptance of their own sexual identity, less internalized homophobia, higher self-esteem, more social support, better overall physical and mental health, less substance abuse, and lower risk of suicide. Support from one’s family may also contribute to individual resilience and thriving. Many of these effects continue across the lifespan.[28]

Increasing the acceptance by families, decreasing their rejecting behaviors, and assisting family members of LGBTQ+ people to understand the root causes of their reactions to their queer children will improve the health of LGBTQ+ people. Acceptance includes behaviors that “support [a] youth’s LGBT identity even though you may feel uncomfortable,” “connect youth with an LGBT adult role model,” and “work to make your religious congregation supporting of LGBT members or find a faith community that welcomes your family and LGBT child.”[29] Much of this research has focused on the role of parents in demonstrating acceptance, and less is known about the role of siblings, grandparents, and other extended family. Promising research is showing the importance of siblings and grandparents in the lives of LGBTQ+ people.[30]

Some families experience feelings of loss, grief, and shame, among others, when they find they have LGBTQ+ family members. Loss and grief may result from feeling that they have to give up more heteronormative ideals of marriage or grandchildren for their child. Shame may be related to either latent or blatant anti-LGBTQ+ bias and the fear of being judged by others for having an LGBTQ+ family member. Outside resources may allow families to process their feelings separate from their family members. An important organization supporting the experiences of families with LGBTQ+ family members is PFLAG (formerly known as Parents, Families, and Friends of Lesbians and Gays). PFLAG was started in the United States in 1973 by “a mother publicly supporting her gay son” and has expanded to over two hundred thousand members in four hundred locations.[31] Using a three-pronged approach of advocacy, education, and support, PFLAG’s chapters across the United States function largely as support groups for families and friends to process their feelings and to shift to becoming advocates for their loved ones (figure 8.7).

Research with LGBTQ+ Families

Researchers interested in better understanding LGBTQ+ families and relationships face challenges, such as identifying those who are in same-sex relationships or couples, recruiting samples of adequate size, and adequately representing racial, gender, and sexuality diversity within the population. Because LGBTQ+ people continue to face discrimination from their birth families, places of employment, and communities and ongoing threats from social and legal institutions, some may be hesitant to reveal their identities or relationships. Because same-sex marriage has been legal in the United States only since 2015 and the means of relationship formation have been actively shifting, records available to researchers are limited or incomplete.[32]

Also, a great deal of research that is affirming to LGBTQ+ people relies on exclusionary heteronormative definitions of family that limit LGBTQ+ families to those conforming to a traditional heterosexual model or that suggest ideal LGBTQ+ families are those that attempt to conform to those exclusionary models. These definitions may result in the additional marginalization of families that fail to conform to these definitions (e.g., chosen families, families without children, nonmonogamous families, or polyamorous families). In addition, such research often focuses on white families, neglecting queer families of color, working-class queer families, and other families situated at the intersection of multiple systems of oppression.[33]

LGBTQ+ Families with Children

Although not all families include children, becoming parents can be an important goal for many. Research has suggested that a wide range of motivations push people to become parents, including emotional bonding, personal fulfillment, giving and receiving love, continuing the family line, and not being alone later in life. Other reasons include one’s partner wanting to become a parent or a need to feel complete. Lesbian mothers and gay fathers have reported many of the same motivations for becoming parents, but these motivations may be shaped by the unique context of LGBTQ+ parenthood. For example, a study of the parenting motivations of gay fathers found that some were motivated by the desire to instill tolerance in their children, thereby creating a more tolerant world.[34]

Approximately 48 percent of LGBTQ+ women and 20 percent of LGBTQ+ men under age fifty are raising children.[35] Some are doing so as part of a couple and some as single parents. In addition, approximately 3.7 million children in the United States have a parent who is LGBTQ+, and approximately 200,000 have parents who are part of a same-sex relationship (as either couples or single parents) (figure 8.8).[36]

How Are LGBTQ+ Families with Children Formed?

LGBTQ+ families with children are created several ways. Some may become parents while in a heterosexual relationship, and they come out later in life. Some may be in a relationship with a member of the other sex, but identify as bisexual or nonheterosexual. Others may identify as LGBTQ+, be in a same-sex relationship, and become parents through the use of assisted reproductive technology, surrogacy, adoption, or foster care.[37]

Parents Coming Out as LGBTQ+

Because of societal pressure and expectations, LGB people of older generations may have entered relationships with a different sex partner to avoid admitting their sexual orientation, to avoid stigma and be accepted, or to have children at a time when family-building options for LGB people were unimaginable for most. Children’s reactions to parents’ coming out as LGB range from disbelief and shock to blaming the other parent for the LGB person’s “changed” identity, to feelings of acceptance and love.[38] Some adult children report feeling closer to their parent now that they know.[39] Many of these reactions are mediated by the child’s age and developmental stage at the time of disclosure. In fact, some experts on family communication now suggest that coming out to one’s children is about strengthening and “deepening” the relationship, not divulging a dark secret.[40]

Parents who come out as transgender face experiences similar to those of their cisgender LGB counterparts (e.g., challenges disclosing their sexuality and gaining acceptance from children, ex- and current partners, and extended family members) but also different. First, the child’s age may influence reaction to the disclosure. The younger the children are, the more flexible their thinking and the easier they adapt to the news. Second, finding those who have a similar experience coming out as transgender to their children may be difficult. A transgender parent often needs to connect with other transgender parents in similar circumstances to find support. Third, many transgender parents report that their relationships with their children were “the same or better” after disclosing their identity than they were before disclosure.[41]

Gay and lesbian stepfamilies may also have needs and challenges distinct from either straight families or gay and lesbian families with children.[42] In addition to the challenges of forming a stepfamily, gay and lesbian individuals often have to negotiate whether, how, and whom to come out to and assess the impact of coming out on both the individual and the family. Coparenting with a different-sex ex-spouse or partner can range from supportive to antagonistic and can acknowledge or ignore the person’s new same-sex partner or spouse.

Myths about Same-Sex Parenting and Children in LGBTQ+ Families

Myths associated with same-sex parenting and the experiences of children raised by same-sex parents have negatively influenced the decisions of LGBTQ+ parents and interactions with legal and social services professionals.[43] These myths include concerns that children raised by same-sex parents or in LGBTQ+ households will experience disruptions in their gender identity development or in their gender role behaviors or that they will become gay or lesbian themselves. Other myths suggest these children will have more mental health and behavioral problems; will experience problems in their social relationships and experience more stigmatization, teasing, and bullying; and are more likely to be sexually abused by their parents or parent’s friends. Research has soundly refuted all these myths.

The psychologist Charlotte Patterson conducted some of most cited research debunking the negative myths about same-sex parenting. Her research has explored the behavioral adjustment, self-concepts, and sex role behaviors of children raised in same-sex households, concluding that “more than two decades of research has failed to reveal important differences in the adjustment or development of children or adolescents reared by same-sex couples compared to those reared by other-sex couples.”[44] She points out that the quality of family relationships is the most important predictor of healthy child development. A review exploring the implications and fitness of same-sex parenting for children found that, across twenty-three studies, the most common myths about impaired emotional functioning, greater likelihood of a homosexual sexual orientation, greater stigmatization by peers, nonconforming-gender role behavior and identity, poor behavioral adjustment, and impaired cognitive functioning were simply not true. Children raised by lesbian moms and gay dads were no more likely to experience negative outcomes than children raised by heterosexual parents (figure 8.9).[45]

Both the myths about LGBTQ+ parents and their children and the research refuting the myths have found their way into the family courts. Prejudicial attitudes and stereotypes describing unfit lesbian moms and irresponsible gay dads have historically been used in custody cases to justify punitive court decisions. Research that establishes the fitness of LGBTQ+ parents has been influential in custody cases, and Patterson herself has served as an expert witness in numerous custody and other court cases.[46] LGBTQ+ families’ lives are shaped by the powerful social forces of heterosexism and cissexism. These forces can influence policy and law, including family court cases, so there is a continuing need for unbiased and scientifically rigorous studies on LGBTQ+ family formation and the developmental and social outcomes for children in these families.

Navigating and Changing Systems and Institutions

Some LGBTQ+ people and their allies have seized the moment of societal change by trying to change systems from within, finding private sector corporations to be much more open and agile in response to their needs than public institutions. To not lose customers or employees because of anti-LGBTQ+ sentiment, many corporations are opting to strengthen LGBTQ+ workplace policies and affinity groups.[47] Such policies include equal spousal and partner health care benefits, affirmative transgender health care benefits, gender-neutral bathrooms, and nondiscrimination policies that provide protections for sexual orientation, gender identity, and gender expression (figure 8.10). To capture the progress being made in the private sector, the Human Rights Campaign rates corporations in their annual Corporate Equality Index. Described as a “benchmarking tool on corporate policies and practices pertinent to lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer employees,” these ratings are often used by corporations to demonstrate openness and inclusion.[48]

These corporate workplace gains haven’t come without criticism, however. Some have voiced concerns that private sector openness to LGBTQ+ communities is really just a way of manipulating workers into complacency by “keeping employees happy” and exploiting their need to “seek meaning through their job.” These policies can mask labor violations and exploitative practices, thereby creating the perfect marriage of capitalism and personal identity.[49] These corporate policies and practices are often described as assimilationist—that is, a strategy “that strives for access to those in power [and] is rooted in an interest-group and legislative-lobbying approach to political change.”[50]

Other institutional change from within has occurred in health care and human services agencies. The National Association of Social Workers expressed its support in 2002 for allowing same-sex couples to foster and adopt and has repeatedly issued professional support for same-sex marriage—for example, in 2013 and 2015 in relation to Supreme Court rulings.[51] In 2004, the American Medical Association issued a similar statement supporting adoption, and in 2012, issued support for same-sex civil marriage. In 2013, the American Academy of Pediatricians expressed its support for allowing same-sex couples to marry and to become foster and adoptive parents. Other professional groups (for example, the American Psychiatric Association and the American Counseling Association) have followed suit. Collectively, these statements recognize that combating discrimination against LGBTQ+ families is important, discrimination is itself a public health issue, and families should receive professional and unbiased care and services.

Parenting and Family Building

Family and adoption rights are one way that LGBTQ+ parents are discriminated against if they have biological children, want to adopt, or want access to infertility treatment. Only five states actively ban discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity for foster and adoptive parents, an additional three states ban discrimination based on sexual orientation, and ten states have laws that allow discrimination against LGBTQ+ prospective foster parents. Most states are largely silent on the topic, opening up a range of treatment toward same-sex adopting families, from active discrimination that is based in law to indifference.[52] Little change has been made to recognize same-sex parents despite the overwhelming evidence that being raised in an LGBTQ+ family is not inherently harmful or destructive to the children.[53]

Numerous studies have, however, documented the health and stress impacts of unequal laws on families that are headed by same-sex couples. For instance, should a child fall ill, a parent who is not legally recognized may be excluded from making medical decisions or may be separated from their child during an emergency because they are not recognized by medical staff as a parent or guardian. Unnecessary legal hurdles and simultaneous societal discrimination against same-sex households appear to be the root of stress, not the LGBTQ+ parents themselves.[54]

Legal Systems

Same-sex couples report navigating many legal challenges that vary depending on how the couple structures their family life. Interviews with fifty-one LGB parents in California found that the law affected their lives and decisions in three dominant arenas: (1) how to have children, (2) where to live, and (3) how their family was (or wasn’t) recognized.[55] Although some legal protections exist nationally, legal protections for LGBTQ+ families vary widely by state, highlighting the need to carefully consider the three arenas when determining how to best protect one’s family.

LGBTQ+ polyamorous couples who wish to have their entire family recognized and legally protected face numerous challenges, the biggest being that in almost all states and countries you may designate only one spouse in a legal marriage. These designations often mean that polyamorous couples cannot obtain health insurance for all their spouses or partners.[56]

Health Care and Human Services Providers

Same-sex couples, with or without children, report unequal treatment in health care and human services care compared with their heterosexual and cisgender peers. For same-sex couples seeking health care for their children, invisibility, or not being recognized by health care providers as a family unit, is one barrier to quality health care. A survey of nursing and medical students found that 69 percent did not directly ask about the relationship among family members or were unsure if they should directly ask if the two same-sex adults were a couple responsible for the child receiving care.[57] Not being seen and legitimized as a family unit is stressful to the couple and can also complicate care if one parent is not recognized as a guardian or is left out of decision-making processes.

Supportive and affirming policies, practices, and professionals are particularly needed to serve the aging LGBTQ+ community. The aging LGBTQ+ population is underserved and experiences higher risk of medical issues compared with their heterosexual peers.[58] Having higher need, combined with stigma from health care providers, leads to unsatisfactory and unequal treatment in out-of-home care. Couples who are aging and require out-of-home care often report anxiety about how they will be treated by staff and whether they will be seen, treated, and respected as a couple.[59] One study found that over half of elder LGBTQ+ adults were opposed to assisted living, and 80 percent were opposed to out-of-home care because of fear of discrimination, including how their partner would be treated and whether their advance directives for health care would be recognized and respected.[60]

Discrimination from human services providers in care and decision-making has long been of concern. For example, LGBTQ+ people in general and same-sex couples in particular face bias and outright discrimination when trying to adopt a child from foster care or through a social services agency. A survey of 169 diverse gay and lesbian parents found that over one-third were not emotionally supported when they were seeking to adopt (their adoption worker did not express support for them), in contrast to the experience of straight adopting couples, and nearly 15 percent felt very stressed when coming out as lesbian or gay to their adoption worker, fearing that it would limit their chances of having a child placed in their home.[61]

Schools and Educators

LGBTQ+ families with children interact with education systems with varying degrees of support for their families and identities. Challenges may include being treated differently from straight and cisgender parents, not having their family structures represented in the curriculum, and not having both same-sex parents respected as equal parents when decisions need to be made about their child. In addition, some LGBTQ+ parents have described trying to help their children explain their family structure (e.g., “I have two dads”) to other children at school, which is especially difficult when the classroom lacks LGBTQ+ cultural competency. These challenges can have a negative effect on the well-being of LGBTQ+ families and their children. College teaching and education programs need to place greater emphasis on training future educators, before they enter the classroom, in how to demonstrate cultural competence when working with LGBTQ+ families.[62]

Trends and Changes in the Legal Landscape

As Patterson and colleagues have pointed out, today’s quickly shifting legal landscapes regarding LGBTQ+ relationships, marriage equality, reproductive technologies, and foster parenting and adoption by LGBTQ+ individuals have brought challenges but also promise for improving the lives of LGBTQ+ families. However, these advances remain vulnerable to changing attitudes and political majorities. After marriage equality became law through the landmark Obergefell v. Hodges (2015) ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court, state legislatures began considering legislation to limit its influence, and court cases based on the right to religious freedom try to reverse gains. The future legal landscape for LGBTQ+ people appears uncertain.[63]

Strategies for Change: Queer Cautions and Resistance

LGBTQ+ communities, and the families that form within the community, are not monolithic. Therefore, any discussion of family within such a diverse and intersectional community will be a complicated one. For some LGBTQ+ people, the LGBTQ+ movement’s recent emphasis on assimilationist approaches to social change, such as fighting for access to heteronormative institutions like marriage, is misguided and actually privilege heterosexuality over queer lives. Some highlight the diverse and creative ways that LGBTQ+ people create families, emphasizing the importance of choosing families and raising concerns about laws and legally sanctioned institutions that often place limitations on what counts as family.

Some LGBTQ+ people are concerned that vital and limited resources in the fight for things like a national nondiscrimination law have been reallocated to the fight for marriage equality. Thus, ironically, a lesbian living in a state like Texas can now marry her wife but be unable to order a wedding cake if the local baker opposes LGBTQ+ families or marriage. Others look beyond the argument that marriage provides a way to gain access to important resources and benefits (e.g., health insurance, inheritance and property rights, visitation rights in hospitals and jails, adoption rights), instead asking why these benefits must be tied to marriage in the first place. Some scholars suggest that queer communities should reject all notions of family building altogether. They point out that rather than making these benefits available to all, marriage equality has created a new set of boundaries that define who has access to certain privileges that remain inaccessible for others in the broader LGBTQ+ community.[64]

Profile: LGBTQ+ Family Building: Challenges and Opportunity

Christa Craven

Queer people have a long history of creating family in many different ways, including creating chosen families among adults (and sometimes children) who may not be biologically related. Yet with the enhancement of legal rights in recent years, such as same-sex marriage, many LGBTQ+ people are feeling more pressure than ever to form families that include biological or adopted children or both. People have said to me, “After we got married, the next logical question from our families and friends was, ‘When will you have kids?’” With greater access to reproductive technologies and adoption for same-sex parents over the last few decades, LGBTQ+ people have significant opportunities to build families. However, experts estimate that a quarter of all pregnancies end in loss, and a similar number of adoptions fall through; 12 percent of U.S. women are diagnosed with infertility; and transgender people are often faced with difficult reproductive decisions relating to transition. With the rise in LGBTQ+ family making—the “gayby boom”—the numbers of reproductive losses through miscarriage, stillbirth, failed adoptions, infertility, and sterility have also increased.

In addition to heteronormative assumptions about who should have children, LGBTQ+ intended parents face another layer of invisibility and isolation as they combat the well-documented cultural silence surrounding reproductive loss. Even among those who support LGBTQ+ families, there is often political silencing of queer family-making narratives when they do not produce a happy ending. Moreover, the reproductive challenges LGBTQ+ families continue to face have received little attention and have been exacerbated by increasingly restrictive laws regarding LGBTQ+ adoption and family recognition following the 2016 U.S. elections. LGBTQ+ family making is politicized even within queer communities by progressive efforts to create a seamless narrative of progress toward enhanced marital and familial rights. These contentious political battles often eclipse the challenges and barriers LGBTQ+ parents face in establishing and gaining recognition as families.

Physicians and public health experts estimate that 10–20 percent of all recognized pregnancies in the United States and 30–40 percent of all conceptions end in pregnancy loss. Estimates for other countries vary substantially. The knowledge that a pregnancy has ended is likely higher for LGBTQ+ people, who are often more intentional in planning their families than their straight peers and thus more likely to be doing early home pregnancy tests. Public perception regarding pregnancy loss differs substantially from public health estimates. A 2015 survey of over a thousand U.S. adults showed that 55 percent thought miscarriage was rare (occurring in 5 percent or less of pregnancies).[65] In addition, 12 percent of U.S. women are diagnosed with infertility, and fertility preservation options are not always made available to transgender people considering hormones or surgery. Likewise, a review of U.S. studies among different populations estimates adoption failure rates, or what adoption agencies euphemistically refer to as “disruptions,” of 10–25 percent.[66] Statistics on adoption are not kept in most countries.

I interviewed over fifty LGBTQ+ people to understand how they experience loss, grief, and mourning. They included those who carried pregnancies, nongestational and adoptive parents, and families from a broad range of racial/ethnic, socioeconomic, and religious backgrounds. I found that stories of loss, death, and reproductive challenges that accompany queer family making are often ignored or silenced both inside and outside LGBTQ+ communities, resulting in personal and political isolation. Three examples drawn from my study highlight the need for more inclusive support resources.[67]

Alex and Nora’s Story

When I spoke with Alex and Nora, they had experienced a second-trimester loss less than a year before. Nora, a cisgender lesbian, had physically carried their first daughter, but she had developed health complications that made another pregnancy dangerous for her health. The couple agreed that Alex, who had previously identified as a female-to-male transman, would carry their next child. Alex had adopted a genderqueer lesbian identity after becoming pregnant and was pregnant at the time of our interview. Nora explained how her experience of their loss was not only a physical and emotional one but also personally and legally complex.

In losing our daughter . . . , I lost not only a biological and a physical connection. . . . I also lost the ability to have legal rights [to our future children], to have my name on this child’s birth certificate. . . . I’m not even going to be able to petition for that [where we live].

In 2011, Nora would have had no legal rights to their child borne by Alex because the couple lived in a state where nongestational queer parents were denied access to second-parent adoption of their children. But to Nora, having to formally adopt in any jurisdiction and be evaluated on her fitness as a parent was devastating.

Nonetheless, the couple continued to consider pursuing legal adoption in another state or country and then returning to their home state to request a reissued birth certificate that would recognize them both as legal parents. Unlike same-sex marriages or civil unions, which were not recognized in much of the United States before 2015 and not recognized in countries where laws do not permit same-sex unions, adoptions are recognized across jurisdictions. However, financial instability—Nora was a full-time graduate student and Alex an administrative assistant—put this option for giving both of them legal parental status out of the couple’s reach.

Although the couple lived in a liberal midwestern town, the homophobic state and federal laws that governed Nora’s relationship—or lack of legal relationship—with the child borne by her partner heightened her experience of loss. They encountered silencing within queer communities following their loss, which resulted in feelings of isolation. As Alex explained, LGBTQ+ reproductive loss “complicates the political rhetoric. It’s the same reason you don’t hear about gay divorce, because it complicates the political rhetoric of trying to get marriage equality.”

Significant changes in the legal landscape for LGBTQ+ couples and families have occurred in the 2010s, in the United States and throughout the world. After the national recognition of same-sex marriage in 2015 following the Obergefell v. Hodges U.S. Supreme Court case, many LGBTQ+ parents assumed that the presumption of parenthood (that both individuals in a marital union are legal parents to any child born within that union) would be extended to lesbian and gay married couples, as it is for heterosexual couples. However, legal precedent on this issue has been inconsistent, which can leave LGBTQ+ families—even those formed within legal marriages—vulnerable in ways that heterosexual married couples are not. Additionally, any children born to same-sex parents outside a legal marriage must still be formally adopted by the same-sex second parent. In the case that the couple legally marries (or the marriage becomes legally recognized) after the child is born, a stepparent adoption is required.

As of April 2019, only fifteen states allow unmarried parents to petition for second-parent adoption. Laws also exist in some states that allow discrimination against LGBTQ+ parents by adoption agencies that cite religious beliefs against same-sex parenting. In 2019, U.S. legal experts in the American Bar Association acknowledged that, despite the federal recognition of same-sex marriage in 2015, “state-sanctioned discrimination against LGBT individuals who wish to raise children has dramatically increased in recent years.”[68] Many adoptive parents also expressed the fear that homophobia and heterosexism within adoption agencies and among birth families meant they had a higher likelihood of adoption disruption than heterosexual couples.

Mike’s Story

Mike’s particularly heartbreaking story concerned suffering the loss of twins in an adoption. He and his partner, Arnold, had traveled to Vermont to get a civil union during the 1990s and began the adoption process shortly afterward in their home state, which didn’t legally recognize their relationship. With their stable jobs and multiracial family—Mike is a white pediatrician and Arnold an African American high school teacher—the adoption agency they worked with thought they were an ideal family to place biracial twins, whose eighteen-year-old mother had two children already and was living in a battered women’s shelter. They moved forward with an open adoption, meeting with the birth mother on multiple occasions and attending all doctor appointments. When the twins were born, the names that Mike and Arnold gave them appeared on their birth certificates. They spent ten days at home with the twins, but on the tenth day—the last day that birth mothers in their state could legally reclaim their children—at thirty minutes to midnight, the call came.

Mike and Arnold later spoke with staff from their adoption agency, who explained that the birth mother had contacted the biological father of the twins, whom she had been estranged from for months, to tell him that she had put them up for adoption to a gay male couple. He did not approve of having a gay couple raise the twins and convinced her to reclaim them. Despite the birth mother desperately trying to reverse that decision to reclaim the twins and making several calls to Mike and Arnold pleading with them to take the children, the adoption was never formalized. Arnold had struggled with depression previously, and after losing the twins, he began to abuse drugs and alcohol and was unable to return to work. Ultimately, after two years, his addiction led to the end of their relationship.

When we spoke, Mike had recently begun the adoption process again as a single man. This time, however, he was pursuing the adoption of an older child. He said,

[This adoption is] in the foster system, with parents whose parental rights had already been terminated. . . . I don’t want the chance of a birth parent reclaiming again. There’s no way I could do that again. . . . It was like they [the twins] had suddenly died. One minute they were here and the next hour they weren’t here. It was horrible.

Yet as many adoptive parents told me, what was sometimes most difficult about their losses was that the child had not died and that their heartache couldn’t be “a pure sense of grief or loss” that one might experience mourning the death of a loved one. Rather, the child they had come to know and love was “out there somewhere,” and that knowledge created ongoing questions and multilayered grief.

Mike’s story is one of multiple interlocking losses and demonstrates how reproductive losses do not always involve the death of a child, nor are they centered solely around the absence of that child (or children) in one’s life. LGBTQ+ adoptive parents, as well as those who experienced pregnancy loss, infertility, and sterility frequently spoke about the “loss of innocence” that shattered their initial expectations of linear progress surrounding reproduction. Reproductive losses can also result in the loss of dreams for particular kinds of family, as Vero’s story highlights.

Vero’s Story

When Vero came out in the late 1970s, she initially thought she didn’t want to have kids. She explained when we connected over Skype, “I waited longer than I should have . . . being gay, being raised in a Hispanic Catholic family, I didn’t even see it as a reality.” Coming out before the 1990s gayby boom and then leaving home as a teen to serve in the U.S. Army for ten years, like many other LGBTQ+ people who grew up during this time, she felt that forming a family would not be an option for her. But as she found a more supportive community, and many of her LGBTQ+ friends began having kids, “it started to feel like a reality.” Although she didn’t initially wish to carry a child, when she desired children with a long-term partner who was unable to carry, she decided to begin monitoring her ovulation. A year and a half later, that relationship had ended.

But I kept thinking about it and . . . thinking about it and decided that that was something I really wanted with or without that relationship. So, I went on with the process. I had a donor. Everything was good to go. . . . And so, I went to get a physical and during that physical was when they found my cancer. And so, it quickly became—I was staged pretty high and so that quickly became the focus. Even though it [having a baby] was sitting in the back of my head, it was more about getting it [the cancer] staged, having biopsies, and starting treatment, blah blah blah. So, all of that kind of consumed me. . . . I didn’t have to think about it [losing my ability to conceive] right away. But then that came. [Fighting back tears.] I still get emotional about it.

At the time, Vero’s doctors estimated that the advanced stage of her cancer gave her between three months and ten years to live. Although well-meaning friends suggested she consider adoption after initial chemotherapy treatment seemed successful, Vero felt that would not be fair to the child because of the uncertainty about her future health. When I asked Vero how she did cope once she was able to focus on her experience beyond the immediacy of her cancer treatment, she spoke about struggling because, she said, “some people don’t even see my experience as a loss, because I never conceived.” She also had complex feelings that others seemed not to understand:

Once all of the dust settled [after three years of chemotherapy and experimental treatment], I felt very grateful. I mean, if it hadn’t been for this child that I had already named but that I never had, I wouldn’t even be here. [Through tears.] I think what helped me find peace in it all was the gratitude that I was still here and in the last sixteen years that my life would have been completely different. It took a really different turn . . . not a 180, but at least a 45-degree angle [laughing]. It gave me more time to be with all of my friends’ kids. . . . If I’d waited any longer than I did to get my physical, I probably wouldn’t have made it, period. It kind of gave me a different gift. It hit me in a bunch of different ways, and it still hits me every once in a while. I was thinking about it just yesterday: that kid would probably have been fourteen or fifteen by now, and how different my life would be . . . just completely different.

Vero’s experience underscores not only the depth and complexities of losing one’s dream of family but also how grief can shift and evolve over time. As others have frequently said, “It never leaves you.”

Together, Alex and Nora’s, Mike’s, and Vero’s stories paint a vivid picture of the multiple interlocking losses that frequently accompany the loss of a child or dreams of a child. LGBTQ+ parents face general social taboos about discussing reproductive loss, but these expectations are frequently magnified by the legal and political barriers they face in gaining recognition as families. Additionally, they face pressures within LGBTQ+ communities where stories of loss are often silenced in efforts to present a political vision for LGBTQ+ progress.

More inclusive support resources that embrace the diverse realities and challenges of forming LGBTQ+ families are necessary for bereaved LGBTQ+ individuals and families. A notable finding of my study was that over half the participants faced financial struggles in their efforts to expand their families. For most, the urgency to become pregnant or adopt again after a loss drove them to invest more (both financially and emotionally) in those efforts. Yet many discussed this financial investment with a great deal of ambivalence, for fear that it would detract from the emotional loss they experienced. Their stories challenge the assumed affluence of LGBTQ+ individuals who seek to expand their families, even among those who do so via expensive assisted reproductive technology and adoption.

As a queer parent who found few resources after my own second-trimester loss and who bore witness to the ways that my partner was further isolated as a nongestational parent, I have always given this project a public focus. When I published Reproductive Losses: Challenges to LGBTQ Family-Making, I launched a companion website—http://www.lgbtqreproductiveloss.org—an interactive and expanding resource for LGBTQ+ individuals and families. Readers can access an archive of commemorative photos and stories, as well as advice to LGBTQ+ parents experiencing loss and those who support them. But there is far more work to be done to overcome the silencing and isolation surrounding reproductive loss; create opportunities for sustained dialogue among LGBTQ+ intended parents, medical and adoption professionals, and other support professionals; and acknowledge that grappling with grief and mourning—particularly in a moment of legal and political uncertainty—is inescapable for many queer people.

Media Attributions

- Figure 8.2. © Pretzelpaws is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 8.3. is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 8.5. © Kurt Luwenstein Educational Center International Team is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 8.6 © Pretzelpaws is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 8.8. © Caitlin Childs is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 8.9. © Caitlin Childs is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- A. P. Romero, “1.1 Million LGBT Adults Are Married to Someone of the Same Sex at the Two-Year Anniversary of Obergefell v. Hodges,” Williams Institute,June 23, 2017, https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/Obergefell-2-Year-Marriages-Jun-2017.pdf; see also A. R. Flores, J. Herman, G. J. Gates, and T. N. T. Brown, How Many Adults Identify as Transgender in the United States? (Los Angeles, CA: Williams Institute, 2016), https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/How-Many-Adults-Identify-as-Transgender-in-the-United-States.pdf. ↵

- G. J. Gates and F. Newport, “An Estimated 780,000 Americans in Same-Sex Marriages,” Gallup, April 2015, https://news.gallup.com/poll/182837/estimated-780-000-americans-sex-marriages.aspx. ↵

- For resources that strengthen relationships, see F. D. Fincham and S. R. H. Beach, “Marriage in the New Millennium: A Decade in Review,” Journal of Marriage and Family 72, no. 3 (2010): 630–649; and for availability of external resources, see S. S. Rostosky and E. D. B. Riggle, “Same-Sex Couple Relationship Strengths: A Review and Synthesis of the Empirical Literature (2000–2016),” Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity 4, no. 1 (2017): 1–13. ↵

- M. J. Rosenfeld and R. J. Thomas, “Searching for a Mate: The Rise of the Internet as a Social Intermediary,” American Sociological Review 77, no. 4 (2012): 523–547. ↵

- M. J. Rosenfeld, R. J. Thomas, and M. Falcon, “How Couples Meet and Stay Together,” waves 1, 2, and 3: Public version 3.04, plus wave 4 supplement version 1.02 (computer files), Stanford University Libraries, accessed January 6, 2022, https://data.stanford.edu/hcmst. ↵

- D. Adams, “What Polyamorous and Multi-parent Families Should Do to Protect Their Rights,” Prima Facie (blog), LGBT Bar, December 11, 2018, https://lgbtbar.org/bar-news/what-polyamorous-multi-parent-families-should-do-to-protect-their-rights/. ↵

- For the study of gay men in Britain, see G. Gremore, “‘Bro-Jobs’ Author Talks Straight Man-on-Man Sex and ‘Repressed Homosexual Desire,’” Queerty, August 6, 2015, https://www.queerty.com/bro-jobs-author-talks-straight-man-on-man-sex-and-repressed-homosexual-desire-20150806; for the study of gay male couples in the Bay Area, see C. C. Hoff and S. C. Beougher, “Sexual Agreements among Gay Male Couples,” Archives of Sexual Behavior 39, no. 3 (2010): 774–787; for the related study showing equal numbers, see C. C. Hoff, S. C. Beougher, D. Chakravarty, L. A. Darbes, and T. B. Neilands, “Relationship Characteristics and Motivations behind Agreements among Gay Male Couples: Differences by Agreement Type and Couple Serostatus,” AIDS Care 22, no. 7 (2010): 827–835; for a study finding different levels, see J. T. Parsons, T. J. Starks, K. E. Gamarel, and C. Grov, “Non-monogamy and Sexual Relationship Quality among Same-Sex Male Couples,” Journal of Family Psychology 26, no. 5 (2012): 669–677, https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029561; and for higher rates of agreement to be monogamous, see S. W. Whitton, E. M. Weitbrecht, and A. D. Kuryluk, “Monogamy Agreements in Male Same-Sex Couples: Associations with Relationship Quality and Individual Well-Being,” Journal of Couple and Relationship Therapy 14 (2015): 39–63. “The term ‘monogamish’ was first coined a few years ago by relationship and sex columnist Dan Savage, who shared that the arrangement he has with his long-term partner, in which they’re committed to each other but can have sex with others, is not just a phenomenon for gay men.” A. Syrtash, “What It Really Means to Be Monogamish,” Glamour, May 9, 2016, https://www.glamour.com/story/what-is-monogamish. ↵

- T. D. Conley, A. C. Moors, J. L. Matsick, and A. Ziegler, “The Fewer the Merrier? Assessing Stigma Surrounding Consensually Non-monogamous Romantic Relationships,” Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy 13, no. 1 (2012): 1–29. ↵

- Riese, “Here’s the Salacious Sex Statistics on Queer Women in Non-monogamous vs. Monogamous Relationships,” Autostraddle,June 9, 2015, https://www.autostraddle.com/heres-the-salacious-sex-statistics-on-queer-women-in-non-monogamous-vs-monogamous-relationships-290347/. ↵

- C. Kamen, M. Burns, and S. R. H. Beach, “Minority Stress in Same-Sex Male Relationships: When Does It Impact Relationship Satisfaction?,” Journal of Homosexuality 58,no. 10 (2011): 1372–1390; D. M. Frost and I. H. Meyer, “Internalized Homophobia and Relationship Quality among Lesbians, Gay Men, and Bisexuals,” Journal of Counseling Psychology 56 (2009): 97–109; D. M. Frost and I. H. Meyer, “Internalized Homophobia and Relationship Quality among Lesbians, Gay Men, and Bisexuals,” Journal of Counseling Psychology 56 (2009): 97–109; E. A. Payne, D. Umberson, and C. Reczek, “Sex in Midlife: Sexual Experiences in Lesbian and Straight Marriages,” Journal of Marriage and Family 81 (2019): 7–23, https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12508. ↵

- I. H. Meyer, “Prejudice, Social Stress, and Mental Health in Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Populations: Conceptual Issues and Research Evidence,” Psychological Bulletin 129 (2003): 674–697. ↵

- Frost and Meyer, “Internalized Homophobia.” ↵

- Kamen, Burns, and Beach, “Minority Stress in Same-Sex Male Relationships.” ↵

- M. Dank, P. Lachman, J. M. Zweig, and J. Yahner, “Dating Violence Experiences of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Youth,” Journal of Youth and Adolescence 43 (2014): 846–857, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-013-9975-8; T. Gillum, “Adolescent Dating Violence Experiences among Sexual Minority Youth and Implications for Subsequent Relationship Quality,” Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal 34, no. 2 (2017): 137–145, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-016-0451-7; D. R. Marrow, “Social Work Practice with Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Adolescents,” Family in Societies 85, no. 1 (2004): 91–99. ↵

- M. Bulman, “Lesbian Couples Two and a Half Times More Likely to Get Divorced than Male Same-Sex Couples, ONS Figures Reveal,” Independent, October 18, 2017, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/lesbian-couples-more-likely-divorced-male-same-sex-marriages-uk-ons-figures-a8006741.html. ↵

- For family as kinship and biology, see L. Steel, W. Kidd, and A. Brown, The Family, 2nd ed. (Houndmills, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012); for family regardless of kinship, see A. P. Edwards, and E. E. Graham, “The Relationship between Individuals’ Definitions of Family and Implicit Personal Theories of Communication,” Journal of Family Communication 9, no. 4 (2009): 191–208, https://doi.org/10.1080/15267430903070147. ↵

- J. D’Emilio, Sexual Politics, Sexual Communities, 2nd ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998). ↵

- A. B. Becker and M. E. Todd, “A New American Family? Public Opinion toward Family Status and Perceptions of the Challenges Faced by Children of Same-Sex Parents,” Journal of GLBT Family Studies 9, no. 5 (2013): 425–448. ↵

- B. Powell, C. Bolzendahl, C. Geist, and L. C. Steelman, Counted Out: Same-Sex Relations and Americans’ Definitions of Family (New York: Russell Sage, 2010), 26. ↵

- K. E. Hull and T. A. Ortyl, “Conventional and Cutting-Edge: Definitions of Family in LGBT Communities,” Sexuality Research and Social Policy 16 (2019): 33; for family and its functional characteristics, see Powell et al., Counted Out. ↵

- M. K. Nelson, “Whither Fictive Kin? Or, What’s in a Name?,” Journal of Family Issues 35, no. 2 (2014): 201–222; D. Braithwaite, B. W. Bach, L. Baxter, R. DiVerniero, J. Hammonds, A. Hosek, E. Willer, et al., “Constructing Family: A Typology of Voluntary Kin,” Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 27, no. 3 (2010): 388–407. See also P. H. Collins, Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment, 2nd ed. (New York: Routledge, 2000). ↵

- K. L. Blair and C. F. Pukall. “Family Matters, but Sometimes Chosen Family Matters More: Perceived Social Network Influence in the Dating Decisions of Same- and Mixed-Sex Couples,” Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality 24 (2015), https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?p=HRCA&u=nysl_oweb&id=GALE|A441585157&v=2.1&it=r&sid=googleScholar&asid=f32e263b. ↵

- Nelson, “Whither Fictive Kin?”; Braithwaite et al., “Constructing Family.” ↵

- A. Stein, “What’s the Matter with Newark? Race, Class, Marriage Politics, and the Limits of Queer Liberalism,” in The Marrying Kind? Debating Same-Sex Marriage within the Gay and Lesbian Movement, ed. M. Bernstein and V. Taylor (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 39–65. For more on chosen families, see K. Weston, Families We Choose: Lesbians, Gays, Kinship (New York: Columbia University Press, 1997). ↵

- P. A. Thomas, H. Liu, and D. Umberson, “Family Relationships and Well-Being,” Innovation in Aging 1, no. 3 (2017), https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igx025; P. Symister, and R. Friend, “The Influence of Social Support and Problematic Support on Optimism and Depression in Chronic Illness: A Prospective Study Evaluating Self-Esteem as a Mediator,” Health Psychology 22, no. 2 (2003): 123–129. ↵

- C. Ryan, D. Huebner, R. M. Diaz, and J. Sanchez, “Family Rejection as a Predictor of Negative Health Outcomes in White and Latino Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Young Adults,” Pediatrics 123, no. 1 (2009): 346–352. ↵

- C. Ryan, S. T. Russell, D. Huebner, R. Diaz, and J. Sanchez, “Family Acceptance in Adolescence and the Health of LGBT Young Adults,” Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing 23, no. 4 (2010): 205–213. ↵

- For negative feelings associated with sexual orientation, see B. A. Feinstein, L. Wadsworth, J. Davila, and M. R. Goldfried, “Do Parental Acceptance and Family Support Moderate Associations between Dimensions of Minority Stress and Depressive Symptoms among Lesbians and Gay Men?,” Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 45, no. 4 (2014): 239–246, https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035393; for accepting families of LGBTQ+ youth, see H. R. Bregman, N. M. Malik, M. J. L. Page, E. Makynen, and K. M. Lindahl, “Identity Profiles in Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Youth: The Role of Family Influences,” Journal of Youth and Adolescence 42, no. 3 (2013): 417–430, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-012-9798-z; for less internalized homophobia, see A. R. D’Augelli, A. H. Grossman, M. T. Starks, and K. O. Sinclair, “Factors Associated with Parents’ Knowledge of Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Youths’ Sexual Orientation,” Journal of GLBT Family Studies 6, no. 2 (2010): 178–198; for higher self-esteem and so on, see Ryan et al., “Family Acceptance in Adolescence and the Health of LGBT Young Adults”; for support from family, see S. L. Katz-Wise, M. Rosario, and M. Tsappis, “Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Youth and Family Acceptance,” Pediatric Clinics of North America 63, no. 6 (2016): 1011–1025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcl.2016.07.005; and for effects across the lifespan, see E.-M. Merz, N. S. Consedine, H.-J. Schulze, and C. Schuengel, “Well-Being of Adult Children and Ageing Parents: Associations with Intergenerational Support and Relationship Quality,” Ageing and Society 29 (2009): 783–802, https://doi.org/10.1017/s0144686x09008514. ↵

- Ryan et al., “Family Rejection as a Predictor of Negative Health Outcomes in White and Latino Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Young Adults.” ↵

- For the importance of siblings, see K. R. Allen and K. A. Roberto, “Family Relationships of Older LGBT Adults,” in Handbook of LGBT Elders, ed. D. Harley and P. Teaster (Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2016); and for grandparents, see K. S. Sherrer, “Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Queer Grandchildren’s Disclosure Process with Grandparents,” Journal of Family Issues 37, no. 6 (2016): 739–764. ↵

- “About PFLAG,” PFLAG, accessed April 26, 2021, https://pflag.org/about. ↵

- For challenges to researchers, see D. Umberson, M. B. Thomeer, R. A. Kroeger, A. C. Lodge, and M. Xu, “Challenges and Opportunities for Research on Same-Sex Relationships,” Journal of Marriage and Family 77 (2015): 96–111, https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12155; for the Supreme Court ruling on same-sex marriage, see Obergefell v. Hodges (No. 14-556) (U.S. June 26, 2015); and for shifting relationship formation, see L. A. Peplau and A. W. Fingerhut, “The Close Relationships of Lesbians and Gay Men,” Annual Review of Psychology 58 (2007): 405–424. ↵

- K. Crenshaw, “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Policies,” University of Chicago Legal Forum, no. 1 (1989): 139–167. ↵

- For motivations, see D. Langdridge, P. Sheeran, and K. Connolly, “Understanding the Reasons for Parenthood,” Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology 23, no. 2 (2005): 121–133; and W. B. Miller, “Childbearing Motivations, Desires, and Intentions: A Theoretical Framework,” Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs 120, no. 2 (1994): 223–258, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8045374; for a need to feel complete, see C. R. Newton, M. T. Hearn, A. A. Yuzpe, and M. Houle, “Motives for Parenthood and Response to Failed In Vitro Fertilization: Implications for Counseling,” Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics 9, no. 1 (1992): 24–31; and for gay fathers’ motivations, see A. E. Goldberg, J. B. Downing, and A. M. Moyer, “Why Parenthood, and Why Now? Gay Men’s Motivations for Pursuing Parenthood,” Family Relations: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Applied Family Studies 61, no. 1 (2012): 157–174. ↵

- G. J. Gates, Demographics of Married and Unmarried Same-Sex Couples: Analyses of the 2013 American Community Survey (Los Angeles, CA: Williams Institute, 2015), https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/Demographics-Same-Sex-Couples-ACS2013-March-2015.pdf. ↵

- G. J. Gates, “Marriage and Family: LGBT Individuals and Same-Sex Couples,” Future of Children 25, no. 2 (Fall 2015): 67–87, https://www.jstor.org/stable/43581973. ↵

- Gates, “Marriage and Family.” ↵

- K. Davies, “Adult Daughters Whose Mothers Come Out Later in Life: What Is the Psychosocial Impact?,” Journal of Lesbian Studies 12, nos. 2–3 (2008): 255–263, https://doi.org/10.1080/10894160802161422; L. Rowello, “How LGBTQ Parents Can Handle Coming Out to Their Children,” Washington Post, October 9, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/2020/10/09/parents-come-out/. ↵

- Davies, “Adult Daughters Whose Mothers Come Out Later in Life.” ↵

- Rowello, “How LGBTQ Parents Can Handle Coming Out.” ↵

- Lambda Legal, “FAQ about Transgender Parenting,” accessed April 26, 2021, https://www.lambdalegal.org/know-your-rights/article/trans-parenting-faq. ↵

- C. Bergeson, A. Bermea, J. Bible, K. Matera, B. van Eeden-Moorfield, and M. Jushak, “Pathways to Successful Queer Stepfamily Formation,” Journal of GLBT Family Studies 16, no. 4 (2020): 368–384, https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428X.2019.1673866; A. M. Bermea, B. van Eeden-Moorefield, J. Bible, and R. E. Petren, “Undoing Normativities and Creating Family: A Queer Stepfamily Experience,” Journal of GLBT Family Studies 15, no. 4 (2019): 357–372; J. M. Lynch and K. Murray, “For the Love of the Children: The Coming Out Process for Lesbian and Gay Parents and Stepparents,” Journal of Homosexuality 39, no. 1 (2000): 1–24, https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v39n01_01; M. R. Moore, “Gendered Power Relations among Women: A Study of Household Decision Making in Black, Lesbian Families,” American Sociological Review 73, no. 2 (2008): 335–356. ↵

- C. J. Patterson and R. E. Redding, “Lesbian and Gay Families with Children: Implications of Social Science Research for Policy,” Journal of Social Issues 52, no. 3 (1996): 29–43. ↵

- C. J. Patterson, “Children of Lesbian and Gay Parents,” Current Directions in Psychological Science 15 (2006): 241, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2006.00444.x. See also C. J. Patterson and J. L. Wainright, “Adolescents with Same-Sex Parents: Findings from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health,” in Adoption by Lesbians and Gay Men: A New Dimension in Family Diversity, ed. D. Brodzinsky and A. Pertman (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 85–110; C. J. Patterson, “Children of Lesbian and Gay Parents,” Child Development 63 (1992): 1025–1042; and C. J. Patterson, “Children of the Lesbian Baby Boom: Behavioral Adjustment, Self-Concepts, and Sex-Role Identity,” in Contemporary Perspectives on Lesbian and Gay Psychology: Theory, Research and Application, ed. B. Greene and G. Herek (Beverly Hills, CA: SAGE, 1994), 156–175. ↵

- N. Anderssen, C. Amlie, and E. A. Ytteroy, “Outcomes for Children with Lesbian or Gay Parents: A Review of Studies from 1978 to 2000,” Scandinavian Journal of Psychology 43 (2002): 335–351. ↵

- For prejudice influencing court decisions, see Patterson and Redding, “Lesbian and Gay Families with Children”; for research establishing the fitness of LGBTQ+ parents, see C. J. Patterson, “Parental Sexual Orientation, Social Science Research, and Child Custody Decisions,” in The Scientific Basis of Child Custody Decisions, 2nd ed., ed. R. M. Galatzer-Levy, L. Kraus, and J. Galatzer-Levy (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2009); and for Patterson as expert witness, see Shelby Frame, “Charlotte Patterson, at the Forefront of LGBTQ Family Studies,” June 26, 2017, American Psychological Association, https://www.apa.org/members/content/patterson-lgbtq-research. ↵

- R. Githens, “Capitalism, Identity Politics, and Queerness Converge: LGBT Employee Resource Groups,” New Horizons in Adult Education and Human Resource Development 23, no. 3 (2009): 18–31. ↵

- For the most recent index, see Human Rights Campaign, “Corporate Equality Index,” https://www.hrc.org/campaigns/corporate-equality-index. ↵

- Githens, “Capitalism, Identity Politics, and Queerness Converge,” 18. ↵

- C. A. Rimmerman, The Lesbian and Gay Movements: Assimilation or Liberation? (New York: Routledge, 2015), 12. ↵

- United States v. Windsor, 570 U.S. 744 (2013); Obergefell (2015). ↵

- Movement Advancement Project, 2019, https://www.lgbtmap.org/. ↵

- A. E. Goldberg, Lesbian and Gay Parents and Their Children: Research on the Family Life Cycle (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2010); S. Golombok and S. Badger, “Children Raised in Mother-Headed Families from Infancy: A Follow-Up of Children of Lesbian and Single Heterosexual Mothers, at Early Adulthood,” Human Reproduction 25(2010): 150–157; J. G. Pawelski, E. C. Perrin, J. M. Foy, et al., “The Effects of Marriage, Civil Union, and Domestic Partnership Laws on the Health and Well-Being of Children,” Pediatrics 118, no. 1 (2006): 349–364. ↵

- E. C. Perrin, B. S. Siegel, and Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health of the American Academy of Pediatrics, “Promoting the Well-Being of Children Whose Parents Are Gay or Lesbian, Pediatrics 131 (2013): 1374–1383. ↵

- N. K. Park, E. Kazyak, and K. Slauson-Blevins, “How Law Shapes Experiences of Parenthood for Same-Sex Couples,” Journal of GLBT Family Studies 12 (2016): 115–137. ↵

- A. L. Johnson, “Counseling the Polyamorous Client: Implications for Competent Practice,” VISTAS Online, American Counseling Association Professional Information/Library, article 50. ↵

- R. Chapman, R. Watkins, T. Zappia, P. Nicol, and L. Shields, “Nursing and Medical Students’ Attitude, Knowledge and Beliefs Regarding Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Parents Seeking Health Care for Their Children,” Journal of Clinical Nursing 21 (2012): 938–945. ↵

- S. Morrison and S. Dinkel, “Heterosexism and Health Care: A Concept Analysis,” Nursing Forum 47 (2012): 123–130. ↵

- S. D. Erdley, D. D. Anklam, and C. Reardon, “Breaking Barriers and Building Bridges: Understanding the Pervasive Needs of Older LGBT Adults and the Value of Social Work in Health Care,” Journal of Gerontological Social Work 57, nos. 2–4 (2014): 362–385, https://doi.org/10.1080/01634372.2013.871381. ↵

- K. M. Hash and F. E. Netting, “Long-Term Planning and Decision-Making among Midlife and Older Gay Men,” Journal of Social Work in End-of-Life and Palliative Care 3 (2007): 59–77. ↵

- S. Brown, S. Smalling, V. Groza, and S. Ryan, “The Experiences of Gay Men and Lesbians in Becoming and Being Adoptive Parents,” Adoption Quarterly 12, nos. 3/4 (2009): 229–246. ↵

- Brown et al., “The Experiences of Gay Men and Lesbians in Becoming and Being Adoptive Parents.” ↵

- C. J. Patterson, R. G. Riskind, and S. L. Tornello, “Sexual Orientation and Parenting: A Global Perspective,” in Contemporary Issues in Family Studies: Global Perspectives on Partnerships, Parenting, and Support in a Changing World, ed. A. Abela and J. Walker (New York: Wiley/Blackwell, 2014), https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/9781118320990.ch13; for the uncertain legal landscape, see E. Kazyakand and M. Stange, “Backlash or a Positive Response? Public Opinion of LGB Issues after Obergefell v. Hodges,” Journal of Homosexuality 65, no. 14 (2018): 2028–2052; and S. Miller, “3 Years after Same-Sex Marriage Ruling, Protections for LGBT Families Undermined,” USA Today, June 4, 2018, https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2018/06/04/same-sex-marriage-ruling-undermined-gay-parents/650112002/. ↵

- See, e.g., L. Edelman, No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004). ↵

- J. Bardos, D. Hercz, J. Friedenthal, S. A. Missmer, and Z. Williams, “A National Survey on Public Perceptions of Miscarriage,” Obstetrics and Gynecology 125, no. 6 (June 2015): 1313–1320, https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000000859. ↵

- Child Welfare Information Gateway, Adoption Disruption and Dissolution (Washington, DC: Children’s Bureau, June 2012), https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubPDFs/s_disrup.pdf. ↵