Private: Part IV: Prejudice and Health

Chapter 6: Prejudice and Discrimination against LGBTQ+ People

Sean G. Massey; Sarah R. Young; and Ann Merriwether

Introduction

In the decades since the 1969 Stonewall rebellion provided a symbolic turning point in the critical and community consciousness of LGBTQ+ people, a great many things have changed: a number of states have passed antidiscrimination and hate-crime legislation, openly LGBTQ+ people have been elected to public office, and marriage equality has become law in the United States and in many countries around the world. Representations of LGBTQ+ people have expanded because of community organizing, including activism in response to the AIDS epidemic, increasing popular interest in LGBTQ+ lives, the proliferation and widespread use of the internet and social media, and the emergence of an LGBTQ+ consumer market. National rights organizations focused on LGBTQ+ lives have become more visible and have piqued the interest of social scientists and educators.

However, these years have also witnessed ongoing anti-LGBTQ+ prejudice, discrimination, and violence. According to findings from the survey “Discrimination in America: Experiences and Views of LGBTQ Americans,” a majority of LGBTQ+ people have at some point been the target of homophobic slurs and negative comments about their sexuality and gender identity, and most have been threatened or harassed or have experienced violence at some point because of their sexual orientation or gender identity.[1] This chapter is an overview of the prevalence and trends of anti-LGBTQ+ prejudice in the United States and the attempts to define and measure it. The chapter describes what is known about the nature, origins, and consequences of this prejudice and reviews the variables that have been found to increase or reduce its impact on the lives of LGBTQ+ people. The chapter discusses the resistance and resilience shown by the LGBTQ+ community in response to anti-LGBTQ+ prejudice and discrimination.

Prejudice and Discrimination

In his book The Nature of Prejudice (1954), the psychologist Gordon Allport describes prejudice as “antipathy based on faulty and inflexible generalization. It may be felt or expressed. It may be directed toward a group or an individual of that group.”[2] Put simply, prejudice is felt when someone holds a negative view of a person without having any reason or experience that justifies that negative view. Discrimination occurs when someone acts on prejudice by harming or disadvantaging a person or group or when someone favors their own group at the expense of the other group.[3] Prejudice toward LGBTQ+ people has been found to result in discrimination, including anti-LGBTQ+ violence, bullying and harassment in schools, employment discrimination against LGBTQ+ people, and limited access to health care and other social goods.

Violence against LGBTQ+ People

In 1998, Gwendolyn Ann Smith (figure 6.1) established November 20 as Trans Day of Remembrance as a time to speak the names of all the transgender individuals who were killed in antitrans violence over the previous year. In 2016, according to the National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs, 1,036 incidents of LGBTQ+ hate violence were reported by survivors. Of those targeted by this violence, 47 percent identified as gay, 17 percent as lesbian, 14 percent as heterosexual, 8 percent as queer, and 8 percent as bisexual. Over half those targeted in these incidents identified as transgender, and 61 percent identified as a person of color. That same year, 77 hate-violence-related homicides against LGBTQ+ and HIV-affected people were reported. Of these homicides, 49 occurred during the Pulse nightclub shooting in Orlando, Florida. Even without considering the Pulse shootings, 2016 saw a 17 percent increase in anti-LGBTQ+ homicides from 2015. Of these homicides, 79 percent of the victims were people of color, and 68 percent were transgender or gender nonconforming.[4]

This violence isn’t isolated to a particular part of the county. The Anti-Defamation League has tracked the incidence of hate crimes across the country and provides an interactive map showing hate crimes involving both sexual orientation and gender identity. A quick glance at the map shows hate crimes against LGBTQ+ folks happen everywhere, in all fifty states.[5] Unfortunately, these statistics are likely an underrepresentation of the crimes that actually occur. Many victims of hate crimes are hesitant to come forward—because of fear of retaliation if they do; fear of being outed to family, friends, and coworkers; or the belief that coming forward won’t result in positive change.[6]

Bullying, Teasing, and Harassment

Anti-LGBT prejudice also affects LGBTQ+ youth in schools and online. The harassment, bullying, and victimization they experience contributes to lower self-esteem, poorer academic performance, and increased truancy among LGBTQ+ youth. In addition, it leads to feeling less connected to school and having lower achievement goals, and it correlates with higher levels of depression, more suicidal thoughts and attempts, increased substance use, and more sexual risk-taking.[7]

Some states have passed laws to protect LGBTQ+ students from this harassment, bullying, and violence in their schools. One example is New York State’s Dignity for All Students Act of 2012. The goal was to provide students with school environments that are free from discrimination and harassment based on gender, race, religion, sexual orientation, or gender identity.[8] The legislation provides guidelines for students, teachers, and schools, and it institutes a zero-tolerance policy regarding bullying in schools (see chapter 9). Unfortunately, many schools have failed to implement key components of the act, lack staff with adequate knowledge about its requirements, or have failed to adequately track and report incidents of harassment and bullying that fall within the guidelines.[9]

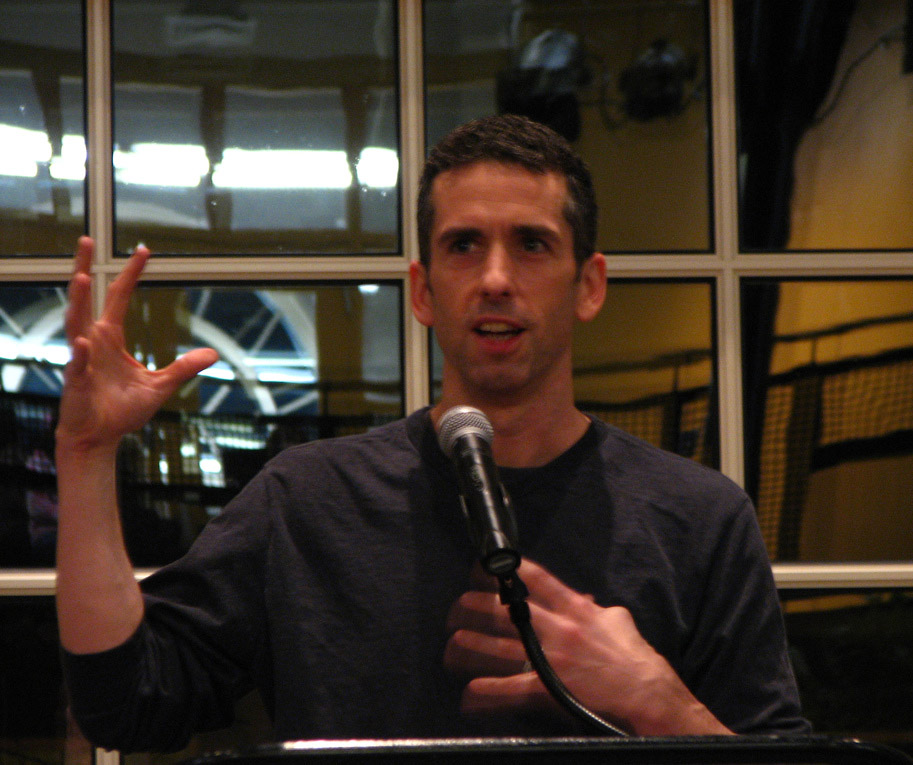

Another resource for LGBTQ+ youth is the It Gets Better Project, founded in 2010 by Dan Savage (figure 6.2) and his partner, Terry Miller. This nonprofit organization attempts to “uplift, empower, and connect lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer . . . youth around the globe” by educating about the negative effects of bullying and harassment and working to build self-esteem for LGBTQ+ youth.[10]

Employment Discrimination

Anti-LGBTQ+ prejudice can also lead to employment discrimination. According to the “Discrimination in America” survey of LGBTQ+ Americans, 20 percent of respondents reported experiencing employment discrimination when applying for a job and in terms of compensation and promotions.[11] These results are even worse for LGBTQ+ people of color. Starting in the 1980s and continuing into the twenty-first century, some states passed employment nondiscrimination laws that offered some protections for LGBTQ+ people, although many of these laws applied only to sexual orientation, leaving out protections for gender expression and identity.

Legislative efforts at the federal level to provide protections against discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity and expression were largely unsuccessful. The Employment Non-discrimination Act, a bill that would protect lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people from employment discrimination, was introduced in Congress every year from 1994 to 2013. The bill came close to passing on at least one occasion, but the inclusion of transgender rights created divisions among both supporters and opponents. Moreover, as support for the bill increased, so too did the claims that these protections would violate the religious freedom of those who see homosexuality as a sin, resulting in the addition of religious-exemption language in versions of the bill. These exemptions concern many longtime advocates for LGBTQ+ rights, who argue that they effectively allow religious organizations to discriminate against LGBTQ+ individuals. Some groups, like Lambda Legal, have even pulled their support for the legislation for this reason.

From 2015 on, LGBTQ+ rights advocates moved to support the Equality Act, a bill with a range of broader protections than the proposed Employment Non-discrimination Act, including protections related to gender identity. The Equality Act would prohibit discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity not only in employment but also in housing, public accommodations, public education, federal funding, credit, and jury service. However, this bill was referred to committee and never passed.

In the absence of federal legislation, LGBTQ+ activists continued to press for justice through the courts. In June of 2020, the U.S. Supreme Court issued the Bostock v. Clayton County ruling, which determined that discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity was a form of sex discrimination and was a violation of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.[12] The Civil Rights Act prohibits discrimination in employment based on sex, race, color, national origin, and religion. According to the legal advocacy group Lambda Legal, this ruling “swept away all the contrary precedent and protected all LGBT workers nationwide.”[13] It remains to be seen whether this decision will survive scrutiny of future, possibly more conservative, courts.

Access to Health Care

Prejudice can also have a negative impact on the quality of and access to health care for LGBTQ+ people. This can happen in several ways. The first way relates to access to employment, because a frequent benefit of employment is access to health insurance. Some states have passed laws that protect LGBTQ+ people from health insurance discrimination, which can result in denial of certain services or coverage altogether. According to the Movement Advancement Project, as of 2021 sixteen states offer protections for both sexual orientation and gender identity; twenty-four states prohibit transgender exclusions in health insurance coverage; six states offer health insurance protections for only gender identity, and twenty-eight states offer no protections for LGBTQ+ health insurance.[14]

Beyond access to health care, prejudice can also affect the quality of health care a person receives. For example, in a 2017 survey conducted by the Center for American Progress, 8 percent of gay, lesbian, and bisexual respondents reported being denied service by a doctor or health care provider; 7 percent reported that doctors had refused to recognize their family, such as a child or same-sex partner; 9 percent reported that providers had used abusive language; and 7 percent experienced unwanted physical contact by a doctor or health care provider. A significantly larger percentage of transgender respondents reported being denied service (29 percent), had doctors refuse to provide care related to gender transition (12 percent), were intentionally misgendered by a doctor (23 percent), experienced abusive language (21 percent), or had unwanted physical contact (29 percent).[15]

Efforts to reform the views and practices of the psychological and medical communities have a long history and are an ongoing project (see chapters 4 and 7). For example, the American Psychiatric Association removed homosexuality from the list of mental illnesses documented in its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual in 1973, and the American Psychological Association has taken a affirmative stance toward LGBTQ+ people since 1975. Additionally, the American Academy of Pediatricians published a statement in 2013 saying that LGB adolescents need health care that is “teen-friendly and welcoming to sexual minority youth.”[16] Nevertheless some mental and physical health practitioners still believe that homosexuality is a disorder, as do some members of the general public.[17]

Public Opinion Polls

According to U.S. public opinion polls from the last few decades, attitudes toward gay men and lesbians have become progressively more favorable. Although attitudes toward transgender individuals have not been surveyed for the same amount of time, results from the 2017 Global Attitudes toward Transgender People survey suggest that a majority of Americans hold positive opinions toward transgender people. Questions that reflect egalitarianism tend to reveal more dramatic pro-LGBTQ+ shifts and suggest that the majority of U.S. residents see gay men and lesbians as deserving of equal and fair (egalitarian) treatment and are generally opposed to discrimination in employment, education, and housing. For example, in 1976, when Gallup asked respondents how they felt about protecting “homosexuals” against employment discrimination in general, only a small majority (56 percent) supported protections, but when they asked again in 2008, the percentage supporting protections increased to 89 percent. Similarly, when Gallup asked respondents in 1979 if they thought homosexual relations between consenting adults should or should not be legal, only 43 percent said they should be legal. When a similar question was asked in 2018, 75 percent said yes, these relations should be legal, and only 23 percent said no. And when asked in 1973 if “it was wrong for same-sex adults to have sexual relationships,” 70 percent said it was always wrong. However, in 2018 that number dropped to 31 percent.[18]

Although the overall pro-LGBTQ+ direction of these public opinion polls since the 1970s is undeniable, they should still be viewed with some caution. Public opinion is not entirely stable from year to year, shifting in an affirming direction for one or two years, then falling back, reflecting shifts in the cultural and political landscapes. In addition, the variety of factors that shape public opinion can result in inconsistent or ambivalent viewpoints. Although egalitarianism continues to have a favorable influence on heterosexuals’ overall evaluations of LGBTQ+ people, many anti-LGBTQ+ values, negative stereotypes, and ego-defensive reactions continue to exert a negative influence. For example, participants’ responses to questions about their comfort in “employing homosexuals” can vary significantly depending on whether the question focuses on the fair treatment of LGBTQ+ people or the moral acceptance of homosexuality.[19] Similarly, attitudes can vary on the basis of the job’s potential for influencing beliefs and the social values of others (e.g., clergy are defenders of morality, elementary school teachers shape the development of children, and service members may symbolize U.S. strength). Finally, the duties associated with the job may trigger antigay stereotypes (e.g., the belief that gay men are all pedophiles and therefore shouldn’t be around children).

Measuring Anti-LGBTQ+ Prejudice

Homophobia

The clinical psychologist George Weinberg is credited with coining the term homophobia.[20] He defined homophobia as the “dread of being in close quarters with homosexuals” and suggested that it was a consequence of several factors, including religion, fear of being homosexual, repressed envy of the freedom from tradition that gay people seem to have, a threat to values, and fear of death.[21] According to Weinberg, some heterosexuals seek symbolic immortality through their children. Their belief that gay people don’t want or can’t have children, and are thereby rejecting this route to immortality, leads to existential anxiety or fear of death. In his highly influential book Society and the Healthy Homosexual (published in 1972), as well as in later interviews, he acknowledged the influence of the gay liberation movement on his thinking.[22] Essays that eventually became chapters of Society and the Healthy Homosexual were published in Gay, a gay liberationist magazine edited by the gay liberation pioneers Jack Nichols and Lige Clarke. Positioning himself solidly within gay liberationist philosophy, Weinberg suggested that he “would never consider a patient healthy unless he had overcome his prejudice of homosexuality.”[23] The psychoanalyst Wainwright Churchill was also influential to scholarly thinking about sexual prejudice at the time. In his book Homosexual Behavior among Males (1967), he describes “homoerotophobia,” a concept similar to homophobia, as the psychological consequence of living in an “erotophobic” society, or one that is afraid of the erotic.[24]

After Weinberg introduced a word for homophobia, research into the study of attitudes toward LGBTQ+ people expanded considerably. Kenneth Smith conducted the first-ever study attempting to measure heterosexuals’ attitudes toward gay men. His work questioned the nature of the homophobic individual. Smith’s homophobia scale, or H scale, was an attempt to measure heterosexuals’ “negative or fearful responding to homosexuality.” Smith found that homophobic people were more “status conscious, authoritarian, and sexually rigid” than nonhomophobic people and concluded that homophobic people may not see homosexuals as belonging to a legitimate minority group that is deserving of rights.[25] Most of the items in the H scale were ego-defensive in nature, assessing participants’ levels of discomfort with being near a homosexual. Items like “It would be upsetting for me to find out I was alone with a homosexual,” “I find the thought of homosexual acts disgusting,” and “If a homosexual sat next to me on a bus I would get nervous” all imply an aversive and affective response possibly due to repressed fear.[26]

Heterosexism and Heteronormativity

According to the lesbian feminist writer and theorist Adrienne Rich (figure 6.3), compulsory heterosexuality—the assumption that everyone is heterosexual and that heterosexuality is natural for men and women—is maintained and reinforced by the patriarchy.[27] This social and political system of male dominance is reinforced by heterosexism, which Gregory Herek describes as “an ideological system that denies and stigmatizes any non-heterosexual form of behavior, identity, relationship, or community.”[28] What results is heteronormativity, an attitude and practice that centers the world around heterosexuality, privileging only that which conforms to the norms, practices, and institutions of heterosexuality.[29] Queer theory expands on the implications of heteronormativity. Combined, heterosexism and heteronormativity shape the world in which LGBTQ+ people live, creating an everyday environment where they are ignored, invalidated, and sometimes punished for not living up to the standards of heterosexuality.

Many of the traditional milestones of everyday life are influenced by heterosexism and heteronormativity. Think about gender roles and their corresponding attitudes and behaviors, body image, gendered attire and comportment, as well as developmental milestones such as dating, marriage, career, and parenthood. All these norms and events are influenced by heterosexism and a corresponding set of heteronormative sexual scripts. These scripts are mental constructions, shaped by culture, that guide individual understanding of relationships and sexual situations.[30] As LGBTQ+ people attempt to navigate these standards and expectations, they frequently encounter challenges to their well-being. It is also important to point out that, although the challenges are intense, many are able to meet these challenges successfully.

Heterosexism and heteronormativity have cast LGBTQ+ individuals as morally vacuous, criminal threats, and mentally ill. Social sanctions existed in most institutions, denying LGBTQ+ people access to faith communities, education institutions, and even families. Discrimination in employment was the norm, resulting in the need for LGBTQ+ people to deny or dissemble in places of employment, when seeking housing, or in public. And although the U.S. Supreme Court has determined that LGBTQ+ people cannot be discriminated against in employment, efforts are underway to limit the scope of this ruling through the pursuit of religious exemptions. Same-sex marriages were not recognized in the United States until 2015, and that change occurred through the courts and not through legislation. In addition, marriage equality continues to be challenged, with legislative and judicial efforts to limit the extent to which same-sex unions must be recognized as valid. The rights of LGBTQ+ people to become or remain parents to children has also seen progress but remains under siege. For example, in 2018, Oklahoma governor Mary Fallin signed a bill that allows private adoption agencies to discriminate against LGBTQ+ couples, allowing them to refuse to place children in LGBTQ+ families if it “would violate the agency’s written religious or moral convictions or policies.”[31]

Microaggressions

Not all acts of discrimination are overt and easily identified, either by the person who is targeted or by witnesses. The mental health of people who are marginalized because of race, ethnicity, gender, and sexuality can also be affected by microaggressions—”brief, daily assaults on minority individuals, which can be social or environmental, verbal or nonverbal, as well as intentional or unintentional.”[32] Because microaggressions are slight, somewhat indirect, and sometimes dismissible, they can be pernicious and difficult to address directly.

Microaggressions have been found to negatively affect mental health, likelihood of accessing health care, and satisfaction with a workplace or educational setting. There are different kinds of microaggressions. Microassaults occur when someone makes a joke or makes a stereotypical generalization about a person based on their group membership. Microinsults refer to rude and insensitive words and behavior that devalue or demean someone’s group. Finally, microinvalidations take place when someone is excluded because of their group or because their experience as the member of a group is invalidated.[33]

LGBTQ+ Minority Stress

Although most people deal effectively with the stress of everyday life, sometimes negative life events can be so severe (what psychologists call major life stressors) or continue for so long (chronic stressors) that they can negatively affect mental and physical health. Members of racial, sexual, and other minority groups who experience stressors as a result of prejudice and discrimination experience what psychologists call minority stress.[34]

LGBTQ+ minority stress extends beyond the regular stress of everyday life or the stress that comes from unexpected life events. It is particularly related to the external experiences that LGBTQ+ people encounter going through life in a heterosexist world, such as discrimination, anti-LGBTQ+ violence, and microaggressions. Research on minority stress also explores the implication of those stressors on LGBTQ+ peoples’ sense of self and psychological well-being, such as self-esteem, depression, and guilt. Research documents how anti-LGBTQ+ prejudice produces negative stressors such as isolation, lack of family acceptance, ostracization by peers, lack of resources and opportunities in schools, less attention from teachers, and less validation of LGBTQ+ peoples’ lives.[35] These stressors add up and negatively affect the mental and physical health of LGBTQ+ people.

Internalized Homophobia and Heterosexism

Because most LGBTQ+ people grow up in environments that are to some degree heterosexist, most are also likely to internalize some of the anti-LGBTQ+ messages they encounter along the way. This internalized homophobia can have mental health consequences, and addressing it is considered an important step in the coming out process. Variables such as community connectedness have been found to help in addressing internalized homophobia. A survey of 1,093 transgender individuals found that stigma relating to participants’ gender identity and expression contributed to their psychological distress, and that trans community and social support helped moderate the distress. A survey of 484 LGB adults found that parental support of a child’s authentic self was associated with lower internalized homophobia and shame as well as better overall psychological health in adults.[36]

Modern and Aversive Prejudice

New conceptualizations and approaches in the measurement of racism (e.g., symbolic prejudice, modern prejudice, and aversive prejudice) and attitudes toward women (e.g., ambivalent sexism) were introduced in the 1980s and 1990s. These approaches explained that, as it became more socially unacceptable to express prejudice, those old-fashioned forms didn’t disappear entirely but went underground and were replaced by more subtle or indirect forms of prejudice. Similarly, in the face of growing social acceptance of LGBTQ+ people, anti-LGBTQ+ prejudice is also often expressed subtly, indirectly, and in ways that avoid direct social condemnation. For example, a study of attitudes toward LGBTQ+ parenting found that people who score high on a measure of modern anti-LGBTQ+ prejudice will evaluate the parenting of same-sex and opposite-sex parents similarly when both sets of parents are engaged in the same positive parenting behaviors. However, when both sets of parents engage in the same negative parenting behaviors (e.g., losing their temper, slapping their child’s hand, and yelling), those same participants will evaluate the parenting of the same-sex couple more negatively than the opposite-sex parents, suggesting that condemnation of the parents’ negative conduct provides a subtle and socially acceptable way to express existing anti-LGBTQ+ prejudice.[37]

Predicting Anti-LGBTQ+ Prejudice

Anti-LGBTQ+ prejudice has been found to highly correlate with other variables, including age, education, location, religiosity, political party and ideology, and sexual conservatism. Personality has also been found to correlate with anti-LGBTQ+ prejudice. People who score higher on measures of right-wing authoritarianism tend to be more deferential to authority figures, see the world in moral absolutes, and be punitive toward those who transgress social norms. These people also tend to hold more negative attitudes toward LGBTQ+ people. In addition, gender and gender-role beliefs have been found to predict attitudes toward LGBTQ+ people. People who support more traditional gender roles and traditional values concerning sexual behavior and family structure tend to express more anti-LGBTQ+ prejudice. Similar correlates have been tied to antitrans attitudes.[38]

Similarly, a national probability sample of heterosexual adults found that more negative attitudes toward transgender people were associated with authoritarianism, political conservatism, religiosity (only for women), rigid views about gender, and lack of contact with transgender people. They also noted that participants’ attitudes toward transgender people were more negative than their attitudes toward LGBTQ+ people.[39]

The contact hypothesis is the idea that contact between groups can improve group relations and reduce prejudice; it was introduced by Allport in 1954. Allport argued that this contact needed to take place in particular situational contexts in which the groups have equal status, that the groups share a set of common goals, are working cooperatively, and have the opportunity to develop emotional connections and empathy.[40] Allport also suggested that there should be support for cooperation and acceptance from authorities or powers that be; the contact must counter the negative beliefs about the group with information that is frequent, consistent, and can be generalized; and the contact should discourage rationalizing the new information as being a special case or subtype of the group.[41] Although prejudice and the threat of discrimination can reduce the possibility of contact between heterosexuals and members of the LGBTQ+ community, heterosexuals with more contact with LGBTQ+ people have been found to hold more favorable attitudes.[42]

The Benefits and Risks of Coming Out

The gay liberation movement of the 1970s advocated for coming out as an LGB person as an important strategy of political change and personal fulfillment. This concept is illustrated in this now famous 1978 quote by the late San Francisco supervisor, and hero of the LGBTQ+ rights movement, Harvey Milk (figure 6.5):

Every gay person must come out. As difficult as it is, you must tell your immediate family. You must tell your relatives. You must tell your friends if indeed they are your friends. You must tell your neighbors. You must tell the people you work with. You must tell the people in the stores you shop in. Once they realize that we are indeed their children, that we are indeed everywhere, every myth, every lie, every innuendo will be destroyed once and all. And once you do, you will feel so much better.[43]

The benefit and buffering effects of coming out have been well established in the literature. Ilan Meyer’s LGBTQ+ minority stress model connects minority identification with positive outcomes in terms of coping and having access to the social support resources necessary to address minority stress. The model also highlights how minority identification is related to minority stressors within the individual such as expectations of rejection, concealment, and internalized homophobia. In addition, identification and community connectedness can increase visibility, which may increase vulnerability to things like employment discrimination, harassment, and violence.[44]

Historians and other social scientists have also suggested that the increased visibility of LGBTQ+ people was a critical element in the formation of LGBTQ+ communities and the progress of the LGBTQ+ rights movements. The contact hypothesis, Harvey Milk’s rallying cry of “Come on out!” and research that highlights the importance of role models and positive representatives in various forms of media all suggest that coming out and increasing the visibility of LGBTQ+ people is an important and often positive strategy for improving social attitudes. As we stated earlier in this chapter, increased visibility does come with risks. However, positive contact between heterosexuals and LGBTQ+ people has been found to result not only in positive attitude change but also in the possibility of increasing the dominant group’s identification with the marginalized group, creating the possibility of allyship—the mobilization of heterosexuals to work toward change benefiting the LGBTQ+ community. As intergroup and interpersonal contact, as well as subsequent social networks, continues to expand into the virtual world through online communities, social networking, and hookup and dating apps, these forms of social interaction will likely continue to shape beliefs about and attitudes toward LGBTQ+ people, create new contexts for minority stress, and expand possibilities for social support and the resources available to LGBTQ+ people.[45]

Conclusion

Although progress in LGBTQ+ rights has been made and attitudes toward LGBTQ+ people have changed in the last few decades, the implications of anti-LGBTQ+ prejudice and discrimination remain serious. It is critical that efforts to change these attitudes continue and that LGBTQ+ affirmative social scientists, educators, and practitioners continue to develop a robust knowledge base to guide these efforts. In addition, a related literature highlights the strength and resilience found in the LGBTQ+ community, even in the face of this adversity.

LGBTQ+ historians and anthropologists like George Chauncey, John D’Emilio, Elizabeth Lapovsky Kennedy and Madeline Davis, and Susan Stryker have helped make visible the courage and perseverance of LGBTQ+ individuals and communities who faced legal risks, social stigma, overt discrimination, and violence across the twentieth century.[46] These are the voices and struggles of a resilient community: the Mattachine Society and Daughters of Bilitis, which organized and built networks of LGBTQ+ people in the shadow of McCarthyism and anti-homosexual witch hunts; the transwomen and transmen, drag queens, queer youth of color, street hustlers, butch dykes, and gay men who took a stand at the Stonewall Inn; the LGBTQ+ people who, amid unimaginable death and sadness brought about by the AIDS epidemic, built organizations, took care of each other, acted up, and fought back against government disdain and neglect; and the people with AIDS, many in the midst of the ravages of the disease, who still found meaning in helping others. These stories of resilience aren’t meant to minimize the dangers or potential for harm. In the words of Harvey Milk, they are simply stories of hope: “Hope for a better world, hope for a better tomorrow, hope for a better place to come to if the pressures at home are too great. Hope that all will be alright . . . and you and you and you, you have to give people hope.”[47]

Profile: Minority Stress and Same-Sex Couples

David Frost

Sexual minority individuals continue to experience prejudice and discrimination as a result of the social stigma that most societies place on sexual behavior and sexual identities outside heteronormative ideals. This stigma persists across many domains of life, including education and the workplace, but is arguably most pronounced in the domain of intimacy and romantic relationships. In this profile, I provide an overview of several studies my colleagues and I have conducted aimed at understanding how sexual minority individuals and members of same-sex relationships experience stigma in the context of their intimate relationships. I demonstrate how experiences of stigma can lead to negative outcomes for members of same-sex relationships in terms of their mental health and in the quality of their relationships. This research illustrates how theories of minority stress can be used to understand how social stigma can be detrimental to the health and relationships of sexual minority individuals and same-sex couples.

The Minority Stress Model

The minority stress model, as proposed by Ilan Meyer, attempts to explain why sexual minority individuals, on average, experience higher rates of mental health problems relative to their straight peers. Noting that these inequalities in mental health are not likely to be caused by sexual orientation itself, the minority stress model contends that the reason for poorer mental health outcomes among sexual minority populations lies in sexual minority individuals having a disadvantaged status in society relative to their straight peers. This disadvantaged social status is created by the stigma that societies place on same-sex sexual behavior and sexual minority identities, which does not apply to straight individuals given the privileging of heterosexuality as normative.[48]

As a result of this disadvantaged social status, sexual minority individuals are exposed to social stress that straight individuals are not. Social stressors include being fired from your job because you are lesbian (i.e., prejudice), being called names because you are bisexual (i.e., harassment), being socially avoided because you are gay (i.e., everyday discrimination), having to worry about when it is safe to disclose your sexual orientation (i.e., stigma concealment), and thinking you are not valued as a person as much as others are because of your sexual orientation (i.e., internalized stigma). These are all examples of social stress that sexual minorities experience that their straight peers do not. As a result of excess exposure to these and other forms of minority stress, sexual minorities are more likely to experience mental health problems like elevated rates of depression, anxiety, substance use, and suicidal ideation. Thus, the minority stress model contends that sexual minority individuals experience higher rates of mental health problems than their straight peers because of excess exposure to social stress stemming from their stigmatized and disadvantaged social status.[49]

Stigma and Minority Stress in Same-Sex Relationships

As of 2020, same-sex marriage is either performed or recognized in thirty-two countries throughout the world, and attitudes toward homosexuality and same-sex marriage are dramatically improved according to opinion polls in most Western countries.[50] However, it is important to recognize that the vast majority of countries across the globe do not legally recognize same-sex couples, and in some countries same-sex sexual behavior continues to be criminalized. Even in countries with equal marriage laws, many same-sex couples experience stigma and discrimination from coworkers, peers, and family. Thus, the domain of intimacy and romantic relationships remains a significant part of sexual minority individuals’ lives in which they continue to experience social stigma.

Minority Stress as a Barrier to Achieving Relationship Goals

To understand how experiences of minority stress in the relational domain might explain inequalities in mental health between sexual minority individuals and their straight peers, my colleagues and I conducted a survey of 431 lesbian, gay, and bisexual (55 percent) individuals and straight-identified (45 percent) individuals living in the United States and Canada. We specifically wanted to examine the extent to which participants felt stress related to experiencing barriers to achieving their goals in romantic relationships (e.g., getting married, buying a house, planning to have children, moving in together) compared with other areas such as the workplace and education. Participants were asked to complete the Personal Project Inventory on the goals they were pursuing across these life domains and the intensity of perceived barriers to the achievement of these goals, which served as our measure of stress. We also asked participants to complete previously validated measures of depression and psychological well-being.[51]

We found that sexual minority individuals reported significantly more depressive symptoms and lower levels of psychological well-being than their straight peers. Sexual minorities also reported more barriers to goal pursuit than straight participants. People who reported more stress in the form of frustrated goal pursuit scored significantly poorer on mental health and well-being outcomes, and their inclusion in models attenuated sexual orientation differences in mental health. Importantly, when we held constant the differences in the stress related to frustrated goal pursuit, differences between sexual minorities and straight individuals in mental health and well-being were much less pronounced. Thus, our research demonstrates that this frustrated goal pursuit is the critical factor explaining sexual minority differences in mental health and well-being. These barriers to relationship projects came from interpersonal sources, like family, friends, and neighbors.

These findings suggest that stigma in intimacy and relationships may prevent sexual minorities from achieving their goals for intimacy and relationships and in doing so contributes to mental health inequalities observed between sexual minority and straight individuals. These findings have relevance to the changing social context regarding marriage equality. Interpersonal attitudes may affect the everyday relationship activities of sexual minority individuals in ways that are detrimental to their health and well-being.

The Persistence of Minority Stress in a Post–marriage Equality Context

To examine whether minority stress continues to affect the mental health of same-sex couples in the United States after access to equal marriage became available, my colleagues and I examined the degree to which the perception of unequal recognition—as a minority stressor—explained variation in mental health above and beyond legal relationship recognition. We predicted that members of same-sex couples with legal marital status would report more positive mental health outcomes compared with members of same-sex couples who were not legally married. We also predicted that perceiving the social climate as not affording equal recognition to same-sex couples would be related to worse mental health for members of same-sex couples, regardless of legal marital status. Dyadic data from both members of 106 same-sex couples—diverse in terms of couple gender, length of relationship, location in the United States, and race/ethnicity—were collected and analyzed. The survey contained measures of legal marital status, perceived unequal social recognition, and mental health outcomes (e.g., depressive symptoms, nonspecific psychological distress, and problematic drinking behavior).[52]

The results demonstrated that perceived unequal relationship recognition predicted poorer mental health, whether or not members of same-sex couples were in a legally recognized relationship. Focusing on potential differences in mental health by levels of legal relationship recognition, the study found that members of same-sex couples recognized as registered domestic partners or civil unions, but not as legal marriages, demonstrated significantly lower levels of mental health compared with those with legal marriages and those with no legal relationship status. Those who were legally married reported the most positive mental health outcomes but were not statistically distinguishable from those with no legal recognition for their relationship.

These findings illustrate a consistent and robust pattern of associations with multiple indicators of mental health, suggesting that the degree to which members of same-sex couples perceive their relationship to have unequal recognition is a meaningful factor underlying mental health outcomes. In other words, although institutionalized forms of discrimination, such as unequal access to legal marriage, have documented associations with mental health in sexual minority populations, the lived experience of perceived inequality likely represents a more proximal form of minority stress. This form of minority stress is one that potentially exists as shared lived experience at the couple level “and may even persist in contexts where structural stigma has been reduced or eliminated.”[53] These findings also highlight how equal access to legal marriage is an important social change but is not sufficient to eliminate long-standing social stigma as a risk for mental health problems faced by sexual minority individuals and members of same-sex couples. The constantly shifting social and policy climate facing sexual minorities and same-sex couples continues to warrant attention from social scientists, public health scholars, and policy makers in light of its potential impact on mental health.

Resilience and Resistance to Minority Stress in Same-Sex Relationships

It is important to qualify that the research findings discussed up to this point pertain to groups of sexual minority individuals and same-sex couples and reflect the average experience of the participants. Not all sexual minority individuals and members of same-sex couples experience minority stress and not all who do are affected by it in the same way. In fact, many sexual minority individuals and members of same-sex couples live healthy lives in rewarding relationships. Recognizing this variability in individual experience highlights how sexual minority individuals and members of same-sex relationships are resilient in the face of minority stress.

An example of this resilience can be seen in a study of the meaning-making processes same-sex couples use in negotiating minority stress in their relationships.[54] To explore how members of same-sex couples potentially exercise resilience in the face of minority stress, I asked ninety-nine people in same-sex relationships to write about their relational high points, low points, decisions, and goals, as well as their experiences of stigma directly related to their relationships. Narrative analysis of these stories revealed that participants had several psychological strategies for making meaning of their experiences of stigma. Some strategies emphasized a negative, delimiting, and contaminating effect of stigma on relationships, as is commonly found in existing research. However, other strategies emphasized how stigma can be made sense of in ways that allow individuals to overcome its negative effects.

For example, some same-sex couples who participated in this research constructed meanings of stigma-related stressors as challenges that reaffirmed their commitment to and bond with their partners. Others saw stigma as providing an opportunity to redefine notions of commitment and relational legitimacy. These narrative strategies for making meaning of stigma-related stressors represent more than simply coping strategies for minority stress. They represent attempts to reclaim experiences of being stigmatized in ways that allow individuals to resist and even thrive in the face of social stigma. Thus, through individual and group-level meaning-making processes of minority stressors, social stigma can, indirectly, result in positive outcomes for sexual minorities’ well-being and same-sex relationships.

Summary

My colleagues and I have conducted studies that collectively demonstrate how social stigma can affect the health and relationships of sexual minority individuals and same-sex couples. These are by no means the only studies on this topic.[55] It is my hope that the details of these studies illustrate the potential utility of minority stress theory to highlight that the continued stigmatization of same-sex couples, even in areas that have progressive laws and policies, puts sexual minority individuals and same-sex couples at risk for negative health and relationship outcomes. This research has been useful for efforts to change laws and policies to be more inclusive of same-sex couples’ rights and to eliminate discrimination against same-sex couples, efforts that are by no means complete and will continue for years to come. However, research on minority stress can also be useful in informing the work of community health workers, counselors, and clinicians working with sexual minority communities to help them cope with, overcome, and resist the potential negative impact of social stigma.[56]

Media Attributions

- Figure 6.2. © Weebot is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 6.3. © K. Kendall is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 6.5. © Ted Sahl, Kat Fitzgerald, Patrick Phonsakwa, Lawrence McCrorey, Darryl Pelletier is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- NPR, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, “Discrimination in America: Experiences and Views of LGBTQ Americans,” 2017, https://cdn1.sph.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/94/2017/11/NPR-RWJF-HSPH-Discrimination-LGBTQ-Final-Report.pdf. ↵

- G. Allport, The Nature of Prejudice (New York: Addison Wesley, 1954), 9. ↵

- J. Dovidio, M. Hewstone, P. Glick, and V. Esses, “Prejudice, Stereotyping and Discrimination: Theoretical and Empirical Overview,” in The SAGE Handbook of Prejudice, Stereotyping and Discrimination, ed. J. F. Dovidio, M. Hewstone, and P. Glick (London: SAGE, 2010), 3–28, http://www.sagepub.com/sites/default/files/upm-binaries/54590_dovido,_chapter_1.pdf. ↵

- National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, and HIV-Affected Hate Violence in 2016 (New York: NCAVP, 2016). ↵

- “ADL Hate Crime Map,” n.d., https://www.adl.org/adl-hate-crime-map. ↵

- F. S. Pezzella, M. D. Fetzer, and T. Keller, “The Dark Figure of Hate Crime Underreporting,” American Behavioral Scientist, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764218823844; M. M. Wilson, “Hate Crime Victimization, 2004–2012: Statistical Tables,” 2014, http://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=4883. ↵

- For lower self-esteem, etc., see J. G. Kosciw, N. A. Palmer, R. M. Kull, and E. A. Greytak, “The Effect of Negative School Climate on Academic Outcomes for LGBT Youth and the Role of In-School Supports,” Journal of School Violence 12, no. 1 (2013): 45–63; for feeling less connection, see J. Pearson, C. Muller, and L. Wilkinson, “Adolescent Same-Sex Attraction and Academic Outcomes: The Role of School Attachment and Engagement,” Social Problems 54 (2007): 523–542; and for mental health, see R. B. Toomey, C. Ryan, R. M. Diaz, N. A. Card, and S. T. Russell, “Gender-Nonconforming Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Youth: School Victimization and Young Adult Psychosocial Adjustment,” Developmental Psychology 46 (2010): 1580–1589. ↵

- New York State Department of Education, “The Dignity Act,” updated July 20, 2020, http://www.p12.nysed.gov/dignityact/. ↵

- New York State Comptroller, “Some NY Schools Not Reporting Bullying or Harassment,” news release, October 13, 2017, https://www.osc.state.ny.us/press/releases/oct17/101317.htm. ↵

- It Gets Better Project (website), accessed April 24, 2021, https://itgetsbetter.org. ↵

- NPR et al., “Discrimination in America.” ↵

- Bostock v. Clayton County, 590 U.S. ___ (2020). ↵

- Lambda Legal, “Bostock v. Clayton County, GA / Zarda v. Altitude Express / RG & GR Harris Funeral Homes Inc v. EEOC,” accessed November 21, 2021, https://www.lambdalegal.org/in-court/cases/bostock-zarda-harris. ↵

- Movement Advancement Project, “Equality Maps: Healthcare Laws and Policies,” accessed April 24, 2021, https://www.lgbtmap.org/equality-maps/healthcare_laws_and_policies. ↵

- S. A. Mirza and C. Rooney, “Discrimination Prevents LGBTQ People from Accessing Health Care,” Center for American Progress, January 18, 2018, https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/lgbt/news/2018/01/18/445130/discrimination-prevents-lgbtq-people-accessing-health-care/. ↵

- For removal of homosexuality from the American Psychiatric Association list of mental illnesses, see R. Bayer. Homosexuality and American Psychiatry: The Politics of Diagnosis (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1981); for the American Psychological Association LGBTQ+ stance, see American Psychological Association, Sexual Orientation and Homosexuality (Washington, DC: APA, 2008), https://www.apa.org/topics/lgbt/orientation; and for the American Academy of Pediatricians statement, see Committee on Adolescence, “Policy Statement: Office-Based Care for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Questioning Youth,” Pediatrics 132, no. 1 (2013): 198–203. ↵

- Institutes of Medicine, The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Patients: Building a Foundation for a Better Understanding (Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2011). ↵

- For attitudes toward gay men and lesbians and survey answers about employment discrimination, see Gallup, “Gay and Lesbian Rights,” accessed April 24, 2021, https://news.gallup.com/poll/1651/gay-lesbian-rights.aspx; for attitudes toward transgender people, see W. Luhur, T. N. T. Brown, and A. Flores, Public Opinion of Transgender Rights in the US (Los Angeles, CA: Williams Institute, 2017), https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/research/public-opinion-trans-rights-us/. Note that in the 1970s, at the time of the survey, homosexual was widely used to describe gay and lesbian people. However, because of its origins in medical and psychiatric discourse, it is today considered by many to be offensive. ↵

- Gallup, “Gay and Lesbian Rights.” ↵

- Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed. (1991), s.v. “homophobia.” ↵

- G. Weinberg, Society and the Healthy Homosexual (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1972), 4. ↵

- R. Ayyar, “George Weinberg: Love Is Conspiratorial, Deviant, and Magical,” GayToday, November 1, 2002, http://gaytoday.com/interview/110102in.asp. ↵

- Weinberg, Society and the Healthy Homosexual, 1. ↵

- W. Churchill, Homosexual Behavior among Males: A Cross-Cultural and Cross-Species Investigation (New York: Hawthorn Books, 1967). ↵

- K. T. Smith, “Homophobia: A Tentative Personality Profile,” Psychological Reports 29 (1971): 1089, 1093. ↵

- Smith, 1094. ↵

- A. Rich, “Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence,” Signs: A Journal of Women in Culture and Society 5 (1980): 631–660. ↵

- G. M. Herek, “The Context of Anti-gay Violence: Notes on Cultural and Psychological Heterosexism,” Journal of Interpersonal Violence 5, no. 3 (1990): 316. ↵

- C. J. Cohen, “Punks, Bulldaggers, and Welfare Queen: The Radical Potential of Queer Politics?,” in Black Queer Studies, ed. E. P. Johnson and M. G. Henderson (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005); M. Warner, “Introduction: Fear of a Queer Planet” Social Text 29 (1991): 3–17, http://www.jstor.org/stable/466295. ↵

- J. H. Gagnon, “The Explicit and Implicit Use of the Scripting Perspective in Sex Research,” Annual Review of Sex Research 1, no. 1 (1990): 1–43; W. Simon and J. H. Gagnon, “Sexual Scripts,” in Culture, Society and Sexuality, ed. R. Parker and P. Aggleton (New York: Routledge, 1984), 31–40. ↵

- J. Fortin, “Oklahoma Passes Adoption Law That L.G.B.T. Groups Call Discriminatory,” New York Times, May 12, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/12/us/oklahoma-gay-adoption-bill.html. ↵

- K. F. Balsam, Y. Molina, B. Beadnell, J. Simoni, and K. Walters, “Measuring Multiple Minority Stress: The LGBT People of Color Microaggressions Scale,” Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 17, no. 2 (2011): 163, https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023244. ↵

- D. W. Sue, C. M. Capodilupo, G. C. Torino, J. M. Bucceri, A. M. B. Holder, K. L. Nadal, and M. Esquilin, “Racial Microaggressions in Everyday Life: Implications for Clinical Practice,” American Psychologist 62, no. 4 (2007): 271–286. ↵

- For general negative life events, see B. P. Dohrenwend, Adversity, Stress, and Psychopathology (New York: Oxford University Press); and B. P. Dohrenwend, “The Role of Adversity and Stress in Psychopathology: Some Evidence and Its Implications for Theory and Research,” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 41 (2000): 1–19; and for minority stress, see I. H. Meyer, “Prejudice, Social Stress, and Mental Health in Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Populations: Conceptual Issues and Research Evidence,” Psychological Bulletin 129, no. 5 (2003): 674–697. ↵

- S. G. Massey, “Valued Differences or Benevolent Stereotypes? Exploring the Influence of Positive Beliefs on Anti-gay and Anti-lesbian Attitudes,” Psychology and Sexuality 1, no. 2 (2010): 115–130. ↵

- For internalized homophobia, see I. H. Meyer and L. Dean, “Internalized Homophobia, Intimacy, and Sexual Behavior among Gay and Bisexual Men,” in Stigma and Sexual Orientation: Understanding Prejudice against Lesbians, Gay Men, and Bisexuals (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 1998), 160–186; for community connectedness, see D. M. Frost and I. H. Meyer, “Measuring Community Connectedness among Diverse Sexual Minority Populations,” Journal of Sex Research 49, no. 1 (2012): 36–49; for the transgender survey, see W. O. Bockting, M. H. Miner, R. E. S. Romine, A. Hamilton, and E. Coleman, “Stigma, Mental Health, and Resilience in an Online Sample of the US Transgender Population,” American Journal of Public Health 103, no. 5 (2013): 943–951; and for the survey of LGB adults, see N. Legate, N. Weinstein, W. S. Ryan, C. R. DeHaan, and R. M. Ryan, “Parental Autonomy Support Predicts Lower Internalized Homophobia and Better Psychological Health Indirectly through Lower Shame in Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual Adults,” Stigma and Health 4, no. 4 (2019): 367–376. ↵

- For aversive racism, see S. L. Gaertner and J. F. Dovidio, “The Aversive Form of Racism,” in Prejudice, Discrimination, and Racism, ed. J. F. Dovidio and S. L. Gaertner (Orlando, FL: Academic Press, 1986), 61–89; for new conceptualizations and approaches, see S. L. Gaertner and J. F. Dovidio, “The Subtlety of White Racism, Arousal, and Helping Behavior,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 35, no. 10 (1977): 691–707; P. Glick and S. T. Fiske, “The Ambivalent Sexism Inventory: Differentiating Hostile and Benevolent Sexism,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 70, no. 3 (1996): 491–512; I. Katz and R. G. Hass, “Racial Ambivalence and American Value Conflict: Correlational and Priming Studies of Dual Cognitive Structures,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 55 (1988): 893–905; J. B. McConahay, “Modern Racism, Ambivalence, and the Modern Racism Scale,” Prejudice, Discrimination, and Racism (Orlando, FL: Academic Press, 1986); D. O. Sears, “Symbolic Racism,” in Eliminating Racism: Profiles in Controversy, ed. I. Katz and S. Taylor (New York: Plenum Press, 1988); J. K. Swim, K. J. Aikin, W. S. Hall, and B. A. Hunter, “Sexism and Racism: Old-Fashioned and Modern Prejudices,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 68, no. 2 (1995): 199–214; and F. Tougas, R. Brown, A. M. Beaton, and S. Joly, “Neosexism: Plus ça change, plus c’est pareil,” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 21, no. 8 (1995): 842–849; and for attitudes on LGBTQ+ parenting, see S. G. Massey, A. Merriwether, and J. Garcia, “Modern Prejudice and Same-Sex Parenting: Shifting Judgments in Positive and Negative Parenting Situations,” Journal of GLBT Family Studies 9, no. 2 (2013) 129–151. ↵

- For anti-LGBTQ+ prejudice correlations and predicted attitudes toward LGBTQ+ people, see G. M. Herek, “Confronting Sexual Stigma and Prejudice: Theory and Practice,” Journal of Social Issues 63, no. 4 (2007): 905–925; for right-wing authoritarianism scores, see B. E. Whitley and S. E. Lee, “The Relationship of Authoritarianism and Related Constructs to Attitudes toward Homosexuality,” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 30, no. 1 (2000): 144–170; for supporters of traditional gender roles and values, see G. Herek and K. A. McLemore, “Sexual Prejudice,” Annual Review of Psychology 64 (2013): 309–333; M. P. Callahan and T. K. Vescio, “Core American Values and the Structure of Antigay Prejudice,” Journal of Homosexuality 58 (2011): 248–262; and M. B. Goodman and B. Moradi, “Attitudes and Behaviors toward Lesbian and Gay Persons: Critical Correlates and Mediated Relations,” Journal of Counseling Psychology 55 (2008): 371–384; and for antitrans attitudes, see A. T. Norton and G. M. Herek, “Heterosexuals’ Attitudes toward Transgender People: Findings from a National Probability Sample of US Adults,” Sex Roles: A Journal of Research 68, nos. 11–12 (2013): 738–753. ↵

- Norton and Herek, “Heterosexuals’ Attitudes toward Transgender People.” ↵

- T. Pettigrew, “Intergroup Contact Theory,” Annual Review of Psychology 49 (1998): 65–85; P. Hill Collins, Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment (Boston, MA: Unwin Hyman, 1990). ↵

- Pettigrew, “Intergroup Contact Theory”; M. Rothbart and O. P. John, “Social Categorization and Behavioral Episodes: A Cognitive Analysis of the Effects of Intergroup Contact,” Journal of Social Issues 41, no. 3 (1985): 81–104. ↵

- T. F. Pettigrew and L. R. Tropp, “A Meta-analytic Test of Intergroup Contact Theory,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 90 (2006): 751–783; Herek and McLemore, “Sexual Prejudice.” ↵

- J. Capehart, “From Harvey Milk to 58 Percent,” Washington Post, March 18, 2013, https://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/post-partisan/wp/2013/03/18/from-harvey-milk-to-58-percent/. ↵

- For the beneficial effects of coming out, see Michael J. Stirratt, I. H. Meyer, S. C. Ouellette, and M. A. Gara, “Measuring Identity Multiplicity and Intersectionality: Hierarchical Classes Analysis (HICLAS) of Sexual, Racial, and Gender Identities,” Self and Identity 7, no. 1 (2007): 89–111; V. C. Cass, “Homosexual Identity Formation: Testing a Theoretical Model,” Journal of Sex Research 20, no. 2 (1984): 143–167; and R. R. Troiden, “The Formation of Homosexual Identities,” in Gay and Lesbian Youth, ed. G. Herdt (New York: Harrington Park Press, 1989), 43–73; and for the LGBTQ+ minority stress model, see Meyer, “Prejudice, Social Stress, and Mental Health in Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Populations.” ↵

- For formation of LGBTQ+ rights movements, see J. D’Emilio, Sexual Politics, Sexual Communities: The Making of a Homosexual Minority in the United States, 1940–1970 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983); and G. Chauncey, Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890–1940 (New York: Basic Books, 1995); for the contact hypothesis, see G. M. Herek and J. P. Capitanio, “‘Some of My Best Friends’: Intergroup Contact, Concealable Stigma, and Heterosexuals’ Attitudes toward Gay Men and Lesbians,” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 22, no. 4 (1996): 412–424; and Allport, Nature of Prejudice; for Harvey Milk, see R. Shiltz, The Mayor of Castro Street (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1982); for role models and positive representatives in media, see GLAAD, GLAAD Media Reference Guide, 10th ed. (New York: GLAAD, 2016), https://www.glaad.org/reference; S. L. Craig, L. McInroy, L. T. McCready, and R. Alaggia, “Media: A Catalyst for Resilience in Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Youth,” Journal of LGBT Youth 12, no. 3 (2015): 254–275; and B. Forenza, “Exploring the Affirmative Role of Gay Icons in Coming Out,” Psychology of Popular Media Culture 6, no. 4 (2017): 338–347; for improving social attitudes, see M. Levina, C. R. Waldo, L. F. Fitzgerald, “We’re Here, We’re Queer, We’re on TV: The Effects of Visual Media on Heterosexuals’ Attitudes toward Gay Men and Lesbians,” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 30, no. 4 (2000): 738–758; and for allyship, see N. K. Reimer, J. C. Becker, A. Benz, O. Christ, K. Dhont, U. Klocke, S. Neji, et al., “Intergroup Contact and Social Change: Implications of Negative and Positive Contact for Collective Action in Advantaged and Disadvantaged Groups,” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 43, no. 1 (2017): 121–136, https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167216676478. ↵

- Chauncey, Gay New York; D’Emilio, Sexual Politics, Sexual Communities; E. L. Kennedy and M. D. Davis, Boots of Leather, Slippers of Gold: The History of a Lesbian Community (New York: Penguin Books, 1993); S. Stryker, Transgender History (Berkeley, CA: Seal Press, 2008). ↵

- H. Milk, “The Hope Speech,” June 25, 1978, https://www.speech.almeida.co.uk/harvey-milk. ↵

- Meyer, “Prejudice, Social Stress, and Mental Health in Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Populations.” ↵

- For social stress, see I. H. Meyer, S. Schwartz, and D. M. Frost, “Social Patterning of Stress and Coping: Does Disadvantaged Social Statuses Confer More Stress and Fewer Coping Resources?,” Social Science and Medicine 67, no. 3 (2008): 368–379; and for minority stress, see Meyer, “Prejudice, Social Stress, and Mental Health in Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Populations.” ↵

- P. M. Ayoub and J. Garretson, “Getting the Message Out: Media Context and Global Changes in Attitudes toward Homosexuality,” Comparative Political Studies 50, no. 8 (2017): 1055–1085; T. Fetner, “US Attitudes toward Lesbian and Gay People Are Better than Ever,” Contexts 15, no. 2 (2016): 20–27. ↵

- D. M. Frost and A. J. LeBlanc, “Nonevent Stress Contributes to Mental Health Disparities Based on Sexual Orientation: Evidence from a Personal Projects Analysis,” American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 84 (2014): 557–566. ↵

- A. J. LeBlanc, D. M. Frost, and K. Bowen, “Legal Marriage, Unequal Recognition, and Mental Health among Same‐Sex Couples,” Journal of Marriage and Family 80, no. 2 (2018): 397–408. ↵

- LeBlanc, Frost, and Bowen, “Legal Marriage, Unequal Recognition, and Mental Health among Same‐Sex Couples,” 405; for minority stress, see Meyer, “Prejudice, Social Stress, and Mental Health in Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Populations.” ↵

- D. M. Frost, “Stigma and Intimacy in Same-Sex Relationships: A Narrative Approach,” Journal of Family Psychology 25, no. 1 (2011): 1–10. ↵

- For a review, see S. S. Rostosky and E. D. Riggle, “Same-Sex Relationships and Minority Stress,” Current Opinion in Psychology 13 (2017): 29–38; and for a meta-analysis, see D. M. Doyle and L. Molix, “Social Stigma and Sexual Minorities’ Romantic Relationship Functioning: A Meta-analytic Review,” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 41, no. 10 (2015): 1363–1381. ↵

- I. H. Meyer and D. M. Frost, “Minority Stress and the Health of Sexual Minorities,” in Handbook of Psychology and Sexual Orientation, ed. C. J. Patterson and A. R. D’Augelli (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), 252–266. ↵

The effort of a social group or social movement to challenge or struggle against another group, policy, or government that is oppressing them.

An individual’s ability to recover, or bounce back, from a stressful or traumatic experience.

Negative emotions, beliefs, or behaviors toward an individual, based on the person’s group membership and not based on prior knowledge or experience with that individual.

The unjust or prejudicial treatment of an individual or group based on their actual or perceived membership in a particular group or class of people (e.g., race, gender identity, or sexual orientation).

Crimes, such as assault, bullying, harassment, vandalism, and abuse, that are motivated by prejudice toward a certain group and that in some jurisdictions incur harsher penalties.

A law in New York State passed in 2010 that seeks to eliminate discrimination and bullying (based on race, physical size, national origin, ethnicity, religion, ability, sexual orientation, gender identity, and sex) in schools through education, modification of district codes of conduct, and the mandated collection and reporting of incident data.

Surveys to measure the views, attitudes, or opinions of the general public on topics, issues, or social problems.

The positive and negative emotions, beliefs, and behaviors that a person holds or exhibits toward another person, group, object, or event.

The political philosophy of believing in the equality of all and in the elimination of inequality.

A response to another person or group that is motivated by the unconscious need to avoid disturbing or threatening thoughts, such as feelings of guilt.

Negative or hostile attitudes toward people who identify as, or are perceived to be, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer. Biphobia and transphobia are also used to describe negative or hostile attitudes toward people who identify, or are perceived to be, bisexual or transgender.

An idea, proposed by the feminist writer and scholar Adrienne Rich in 1980, that patriarchy and heteronormativity cause society to assume and mandate heterosexuality in everyone.

A society, or belief system, that favors or privileges men at the expense of women, in which men hold most of the power and control most of the wealth, and in which women are marginalized.

An attitude and belief based on the idea that everyone is heterosexual or that heterosexuality is the only acceptable sexual orientation.

A societal belief that makes heterosexuality the default and assumes that everyone is heterosexual until proven otherwise; a belief normalizing heterosexuality and othering any other identity or experience apart from heterosexuality.

Common verbal, behavioral, or environmental insults, indignities, and slights that cause harm by communicating, intentionally or unintentionally, hostility and prejudice toward members of a marginalized group.

Social stress resulting from being a member of a social group or having a social identity that is stigmatized by society.

The acceptance or incorporation of anti-LGBTQ+ prejudice or stereotypes by LGBTQ+ people.

Also known as coming out of the closet; a process in the lives of LGBTQ+ people of disclosing one’s sexual orientation or gender identity to others.

A subtle and indirect form of prejudice toward a group that can manifest as the rejection of the policies and initiatives that are designed to help that group achieve equality while also expressing support for the equality of that group.

Prejudice that is expressed toward an individual through subtle discriminatory behaviors, denial that ongoing discrimination against that group continues, or the suggestion that the marginalized group is trying to advance too far, too fast.

A theory of prejudice, originally proposed in the 1980s in the context of aversive racism, that suggests that negative attitudes toward marginalized groups are sometimes manifested indirectly through feelings of discomfort and the avoidance of members of those groups.

A personality characteristic of individuals who easily submit and defer to leaders, or authority figures, they perceive as strong and legitimate; they tend to adhere to social norms and hold negative attitudes toward anyone who challenges those norms, and they support the use of force to preserve norms and bring social order.

A theory, introduced by the psychologist Gordon Allport in the 1950s, suggesting that, under the right conditions, prejudice, stereotyping, and discrimination can be reduced or eliminated by encouraging interaction between members of the majority and the minority groups.

Building a supportive relationship with a marginalized or mistreated group of people that one is not a part of, an effort that continues even when that relationship threatens one’s comfort, status, or relationships with one’s group.

People who have sexual identities that are not straight, including but not limited to lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer, and pansexual.

Sexual or romantic relationships involving two partners who share the sex assigned at birth and gender identity.

A lower place within the social hierarchy of a society, often defined by a lower level of power, lower social value, and exclusion from full and equal access to material and symbolic forms of citizenship.

Stress that emanates from a person’s relationships with other people, other communities, and the general social environment.