Private: Part VI: Culture

Chapter 10: Screening LGBTQ+

Lynne Stahl

What Is LGBTQ+ Film and Media?

What do Robert Zemeckis’s Who Framed Roger Rabbit? (1988), Penny Marshall’s A League of Their Own, and David Fincher’s Fight Club (1999) have in common? According to film news website IndieWire, they’re all among “the best queer films you didn’t know were queer.”[1] The IndieWire reviewer reads homoerotic valences in Fight Club’s plot, which revolves around illicit male-male contact shrouded in secrecy. But if homosexuality never crosses the viewer’s mind, is the film still queer? The question of what counts as LGBTQ+ film and media is anything but straightforward. Many have debated what makes a gay film gay, a queer film queer, and so on. Must the plot revolve around someone’s emergent sexuality, as in Todd Haynes’s Carol (2015) or Donna Deitch’s Desert Hearts (1985)? Does an LGBTQ+ character suffice? How do we know a character’s sexuality unless it is explicitly stated? Must we assume all film characters are straight until proved queer? What about Charles Herman-Wurmfeld’s Kissing Jessica Stein (2001), in which the title character dates a woman and comes out before finally finding the right man? Are films made by queer-identified directors intrinsically queer?

A range of scholars have explored these questions. In a book on the early lesbian filmmaker Dorothy Arzner, for example, Judith Mayne writes that, though Arzner’s films contain no overtly lesbian characters or plots, they devote “constant and deliberate attention to how women dress and act and perform, as much for each other as for the male figures.”[2] Alexander Doty, meanwhile, suggests that in many popular texts, queerness is “less an essential, waiting-to-be-discovered property than the result of acts of production or reception. This does not mean the queerness one attributes to mass culture texts is any less real than the straightness others would claim for these same texts. As with the constructing of sexual identities, constructing the sexualities of texts results in some ‘real thing.’”[3] In other words, queerness may emanate from the viewer as much as from a same-sex kiss onscreen. As Richard Dyer notes, “In the process of investigation, the by, for, and about category frays at the edges.”[4] With these concerns in mind, this chapter outlines the history of queer representations in screen media and considers the ways both texts and audiences produce queerness in the face of legal and cultural restrictions on overtly queer content.

Representation is important for marginalized groups, but applying labels to individuals and content raises ethical issues. With the aim of advocacy and comprehensibility, this chapter makes provisional use of categories such as gay and trans while remaining sensitive to historical contexts. Elsewhere, queer operates as a catch-all for nonnormative sexual identities, behaviors, and aesthetics.

Similarly, the sections of this chapter are makeshift, a subjective organizing tool to render the content more easily digestible. Part of the work of queer theory is to scrutinize and deconstruct categories, and the taxonomies of film genre and textbook chapter applied here are no exceptions.

Finally, this chapter critiques many of the texts it describes. Critique does not necessarily indicate that the texts in question are unworthy of watching. Rather, recognizing their flaws as symptoms of the sociopolitical systems in which they are produced and consumed is essential to the viewing process. Helping readers learn to identify and analyze these systems is, I believe, a textbook’s core responsibility.

Form and Content

Although the thoughts and feelings they generate are real things, remember that media texts never present objective realities. From Madeleine Olnek’s outrageously campy Codependent Lesbian Space Alien Seeks Same (2011) to hard-hitting documentaries such as David France’s The Death and Life of Marsha P. Johnson (2017), films are representations (figure 10.1). They’re created through subjective human processes such as writing, casting, acting, costuming, editing, and more. However realistic and emotionally affecting, characters are works of art and artifice whose lives stop where the film does. Likewise, documentaries are based on real events but are always interpretations of those events—they’re never fully objective.

Analyzing screen media means considering not just what stories are told but also the techniques and processes—cinematography, editing, mise-en-scène, casting, and so on—used to tell them and how those elements work alongside the content to construct meaning. In literary contexts, form refers to the way a story is told, and content refers to the events, plotline, and characters of which it consists. Content might be thought of as the what of a text; form as how it’s depicted. Making a film or a TV episode entails many decisions beyond plot and dialogue, ranging from camera angles to casting, to wardrobe, to sound mixing, and they all produce certain effects. The language of film form offers a means for examining these decisions and their effects.

A trope, meanwhile, is a “common or overused theme or device.”[5] When overused, it becomes a cliché; tropes are discussed further later in the chapter. The frequent trope of dramatic death in LGBTQ+ film, commonly called Bury Your Gays, includes suicide (William Wyler’s 1961 The Children’s Hour, Lea Pool’s 2001 Lost and Delirious, Atom Egoyan’s 2009 Chloe), homicide (Anthony Minghella’s 1999 The Talented Mr. Ripley, Kimberley Peirce’s 1999 Boys Don’t Cry, Ang Lee’s 2005 Brokeback Mountain, Patty Jenks’s 2003 Monster), and HIV/AIDS (Jonathan Demme’s 1993 Philadelphia, Ryan Murphy’s 2014 The Normal Heart, Bryan Singer’s 2018 Bohemian Rhapsody). These tragic plotlines are so ubiquitous that B. Ruby Rich wryly noted that, in 1999, film’s “only lesbian happy ending involve[d] a portal into John Malkovich’s brain.”[6]

Films involving a queer character’s tragic death aren’t necessarily bad or homophobic, but the persistent, minimally varying association of queerness with unnatural death is reductive and harmful in much the same way that the automatic association of HIV/AIDS with male homosexuality is reductive and harmful. Historically, moreover, these tropes have been cultural or legal requisites for representation to exist at all. To understand the reasons why the definition, production, and consumption of LGBTQ+ film and media remain so complicated today, this chapter devotes significant attention to sociohistorical contexts. Because such context is essential to understanding the contemporary conditions and manifestations of LGBTQ+ film and media, the chapter focuses almost exclusively on the United States.

Historical and Legal Contexts

As this chapter’s title suggests, the history of LGBTQ+ film and media is bound up with social and political constraints that have consistently limited the expression and representation of nonnormative genders and sexualities. Restrictions notwithstanding, all sorts of gender and sexual diversity have found ways to make themselves visible and identifiable since cinema’s early days.

Film’s Beginnings through the Hays Code

In the 1930s, the Motion Picture Production Code, often called the Hays Code, established moral guidelines that films produced for public consumption had to follow. These guidelines prohibited or restricted the depiction of subject matter such as profanity, drug trafficking, religious effrontery, and childbirth scenes; a motion picture was not to “lower the moral standards of those who see it.”[7] But before the Code was imposed, films featured more homosexual content than one might expect. See, for example, Harry Beaumont’s The Broadway Melody (1929) and Cecil B. DeMille’s The Sign of the Cross (1932).

Pre-Code depictions of gay and lesbian characters were often caricatured and insulting: mincing, dissolute men and unflatteringly mannish women. These stereotyped conceptions of homosexuality reflect the era’s prevailing notions of inversion—the idea that queerness equated to femininity in a male body or vice versa. In sexologist Richard von Krafft-Ebing’s words, an invert possessed “the masculine soul, heaving in the female bosom.”[8] Though these stereotypes persist today and have been explored in such venues as David Thorpe’s Do I Sound Gay? (2014), queer and feminist theory have helped dispel the assumption that biological sex (male or female) is inherently connected to gender (masculine or feminine), or indeed that there are only two sexes or two genders.

Poverty stopped many from attending movies when the Great Depression hit, so filmmakers tried shock-value tactics to lure audiences. These tactics encompassed controversial material ranging from unprecedented violence to sexual “perversion,” including homosexual characters.[9] Partially in response to this trend, Will Hays, then president of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (now Motion Picture Association of America) banned all gay male characters in film in 1933.[10] Representations of homosexuality were barred under this ban on the basis of representing “sex perversion or any inference of it”; depictions of interracial relationships were also forbidden.[11]

Just because the Hays Code forbade queer content doesn’t mean none existed, however. Think of the pink elephant game, in which the objective is not to think about pink elephants. Knowing something is not supposed to be present often seems to make the possibility of its presence more acute. For this reason, censorship is notoriously ineffective for enforcing silence on a topic. Further, censorship often begets interpretive tendencies that seek out subtexts whose direct expression has been foreclosed—tendencies Chon Noriega has called “reading against the grain.”[12]

McCarthyism and Onward

The Hays Code’s later years dovetailed with the Red Scare of the 1950s and Senator Joseph McCarthy’s anti-Communist smear campaigns. Josh Howard’s documentary The Lavender Scare (2017) explores the wave of homophobia that arose in conjunction with the Red Scare. The 1950s were a time of extreme scrutiny for gay men and lesbians, leading to firings and other forms of discrimination against individuals suspected of same-sex inclinations. Homosexuality was viewed as dangerously subversive and associated with communist activity—a huge stigma during the Cold War years.

Still, film depictions of queer men and occasionally women proliferated during this time. Partly because of the Hays Code’s proscription on positive portrayals of “perversion,” these characters were often villainous or mentally ill. Indeed, the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual listed homosexuality as a mental illness until 1973 and renamed “gender identity disorder” as gender dysphoria only in 2013. It’s unsurprising that depictions of queer characters have frequently conformed to prevailing popular and medical opinion. Queerness and psychological disturbance remain linked in productions such as Darren Aronofsky’s Black Swan (2010), Sonny Mallhi’s The Roommate (2011), and Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s Killing Eve (2018–).

Post–Hays Code Film and Television

The 1960s saw pushes for civil rights and freedom of expression in many walks of life. Uncoincidentally, the Hays Code was finally laid to rest in 1968. Having proved unpopular and largely unenforceable, it was replaced by the precursor to the current rating system, again from the Motion Picture Association of America: G (general audiences), M (mature), R (restricted), and X (under 16 not admitted). The ratings of PG (parental guidance suggested), PG-13 (parental-guidance suggested for those under 13), and NC-17 (under 17 not admitted, replacing X) were added later.

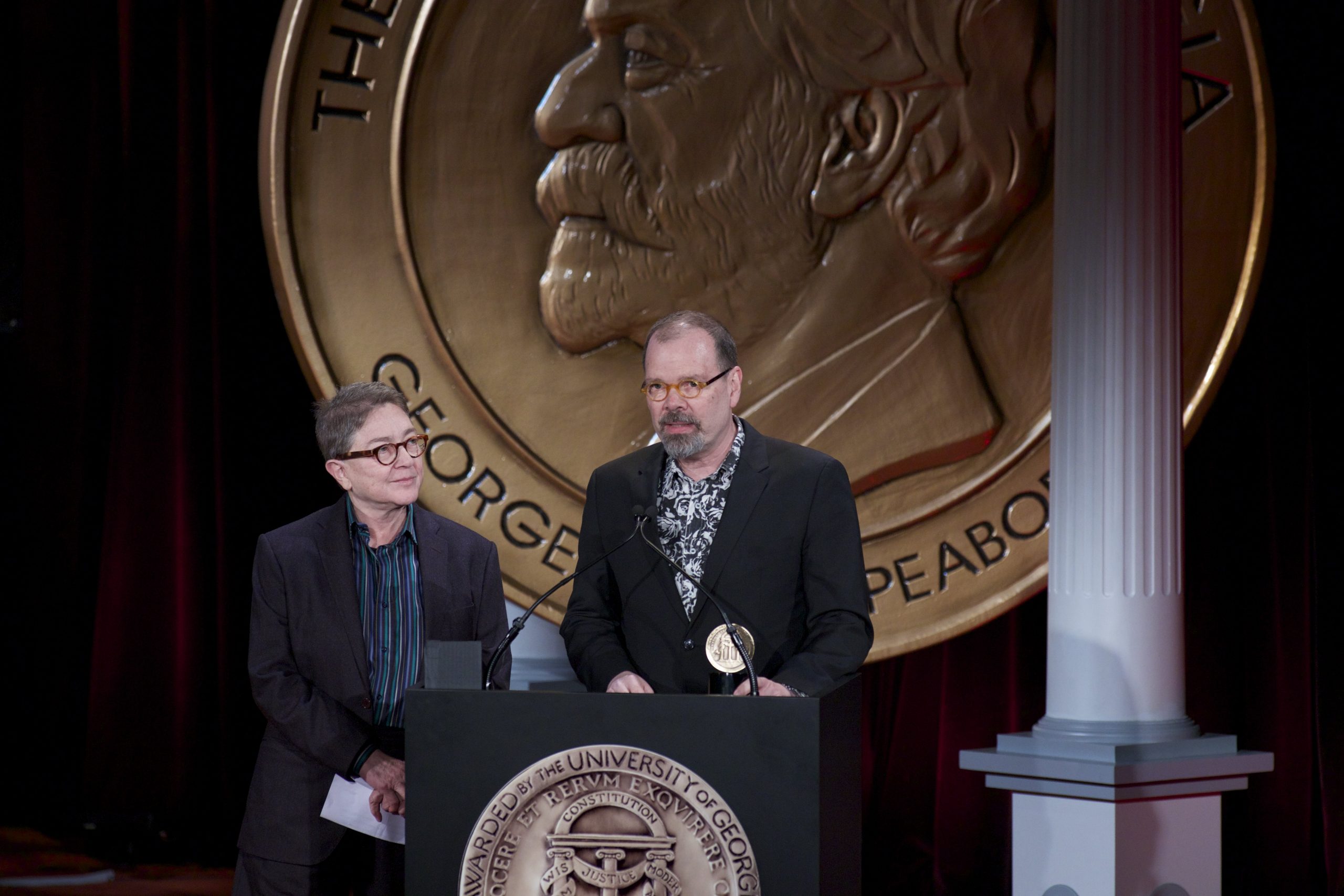

As Vito Russo’s book The Celluloid Closet (adapted into a 1995 documentary by Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman) points out, same-sex representations historically have a much lower threshold for obscenity than do those of heterosexual relations (figure 10.2). That is, a scene where a man kisses another man has been treated as much more obscene—likelier to incur an R rating—than a man kissing a woman.[13]

Free Expression: Then and Now

The first U.S. Supreme Court case to address homosexuality in terms of free speech was One, Inc. v. Olesen in 1958. In it, the court ruled that neutral or positive homosexual content was not inherently obscene. The case had major implications for the media industry, because productions with LGBTQ+ content or themes could not be instantly labeled as pornography even if they flouted the constrictions of the Comstock laws, which blocked content considered obscene from being distributed by mail, or other moral strictures that had historically mandated content considered obscene.

Progressive changes in the portrayal of LGBTQ+ individuals, communities, and issues across media owe much to the continued activism of many groups, from local to international, and changes in public opinion. In 1985, Vito Russo and Jewelle Gomez, among others, founded the Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation (now simply called GLAAD so as not to erase those who identify in ways other than gay or lesbian) in response to negative media coverage of the AIDS crisis. GLAAD promotes inclusive language that does not pathologize. For example, it successfully lobbied the New York Times, the Associated Press, and other outlets to drop “homosexual” in favor of “gay” in 1987. GLAAD also hosts a media awards ceremony each year, compiles indexes related to LGBTQ+ representation in mainstream film, and publishes an annual report addressing the inclusion of LGBTQ+ elements in television.[14]

Underground and Experimental Film

In spite of these legal and cultural restrictions, a gay underground cinema arose with iconoclastic independent filmmakers such as Andy Warhol and Kenneth Anger. Warhol’s Blow Job (1964) consists of a single long take—implicitly of the face of a man on whom another man is performing oral sex. Anger, who worked with the sexologist Alfred Kinsey, made experimental films with homoerotic undertones (and sometimes overtones). Fireworks (1947), which features a group of muscular male sailors and sexually suggestive imagery, led to obscenity charges against a distributor who screened it. A theater manager who screened Anger’s Scorpio Rising in 1963 faced similar charges. In both cases, the charges were dismissed.

Though born in Hollywood, the lesbian filmmaker Barbara Hammer spurned the mainstream (figure 10.3). She directed the groundbreaking Dyketactics in 1973—a four-minute short that consists primarily of fragmented, nonlinear images of naked women walking around outdoors. The later Nitrate Kisses (1992), funded partially by the National Endowment for the Arts, features intimate footage of “deviant” couples, a thread related to the author Willa Cather and her rumored lesbianism, and the victimization of lesbians in Nazi Germany. Unprecedented and avant-garde as Hammer’s style was, she has met criticism from within the feminist community for her association of female bodies with fruit, trees, and other natural images that some view as complicit with the heteropatriarchal construction of women as passive, flowery, and fertile.

Movements, Aesthetics, and Sensibilities

Camp

Amid the post–World War II baby boom, 1940s–1950s suburban America projected an idyllic image of the nuclear family: suburban homes with white picket fences, father as breadwinner, stay-at-home mom. This image and its performative American-ness became the target of parody and critique by dissidents, filmmakers prime among them. One manifestation of such dissent came to be known as camp.

Camp is an aesthetic that privileges poor taste, shock value, and irony, intentionally challenging the traditional attributes of high art. It is often characterized by showiness, extreme artifice, and tackiness—such as the popular pink flamingo lawn ornaments from which John Waters’s iconic film takes its name. Although largely ironic, camp can also devolve from earnestness gone awry, as in attempts at profundity that fall absurdly short of their targets. Paul Verhoeven’s Showgirls (1995) and Steven Antin’s Burlesque (2010) exemplify the latter. In “Notes on ‘Camp,’” the cultural critic Susan Sontag suggests that nothing in nature can be campy (figure 10.4).[15]

Since the 1960s, the camp cinema of John Waters has delighted some audiences while repulsing others. Pink Flamingos (1972), Polyester (1981), and Hairspray (1988) lampoon the strictures and hypocrisies of the suburban United States, featuring the drag queen Divine and innumerable acts of subversion. Divine’s influence went far beyond Waters’s films, too. Legend holds Divine to be the inspiration for the villainous sea witch Ursula in Disney’s The Little Mermaid (1992). More recently, Liz Flahive and Carly Mensch’s comedy series GLOW (2017–) has embraced the campy 1980s phenomenon of the same name, giving fictional life to the erstwhile women’s wrestling venture full of caricatured personae and self-consciously over-the-top storylines.

New Queer Cinema

The rise of independent film festivals such as Sundance and Telluride in the 1970s and 1980s spotlighted smaller productions that lacked the financial backing of major studios, from avant-garde work to indie narrative cinema. Following the liberation-oriented activism of the 1970s–1980s and then the HIV/AIDS crisis, a movement of unconventional, experimental, and unapologetic films emerged in the early 1990s. Rich termed this movement “New Queer Cinema,” describing it as one “favoring pastiche and appropriation, influenced by art, activism, and such new entities as music video. . . . It reinterpreted the link between the personal and the political envisioned by feminism [and] restaged the defiant activism pioneered at Stonewall.”[16]

New queer cinema films such as Gus van Sant’s My Own Private Idaho (1991) and Derek Jarman’s Edward II (1991) featured overtly queer content, often focalized through outsider characters. Many also engaged with or alluded to the AIDS crisis, including Richard Fung’s 1991 Chinese Characters, Marlon Riggs’s 1989 Tongues Untied, Todd Haynes’s 1991 Poison and 1995 Safe, and Gregg Araki’s 1992 The Living End.

Cheryl Dunye’s (figure 10.5) mockumentary The Watermelon Woman (1996) calls out the erasure of Black lesbians in Hollywood and the persistence of racist film tropes over the years. The film follows Dunye’s character as she stages interviews with both fictitious and real-life lesbian activists, including Sarah Schulman and Camille Paglia. Jennie Livingston’s Paris Is Burning (1990) documents New York City ball culture, foregrounding Black and Latinx lives and communities involved in the dance vogue scene. Iconic as it has become, scholars including bell hooks and Judith Butler have questioned the film’s racial politics. Livingston, who is white and from a privileged background, arguably profits off a marginalized community and the unambivalent celebration of drag as a means of subversion and liberation. Critiques notwithstanding, Steven Canals, Brad Falchuk, and Ryan Murphy joined forces to create Pose (2018–), an FX series that draws from Paris Is Burning in its fictionalized representation of the same ballroom culture. Livingston has contributed in directorial and production roles to that production as well.

Mainstream Gay?

Whereas new queer cinema was defined largely by the queer-identified directors, writers, and producers creating its films, LGBTQ+ films began to enter bigger markets in the early years of the 2000s. Ang Lee’s Brokeback Mountain (2005), for example, featured the (straight) A-list stars Heath Ledger and Jake Gyllenhaal as covert lovers. Subsequently, films such as Julie Taymor’s Frida (2002), Lisa Cholodenko’s The Kids Are All Right (2010), Ryan Murphy’s The Normal Heart (2014), Morten Tyldum’s The Imitation Game (2014), and Barry Jenkins’s (figure 10.6) Moonlight (2016) have all featured well-known (and disproportionately straight) actors and achieved mainstream prominence, including major award nominations.

Television and Streaming Media

LGBTQ+ TV

Actress, comedian, and talk show host Ellen DeGeneres (figure 10.7) is now an internationally recognizable figure who regularly appears on the Forbes annual World’s 100 Most Powerful Women lists, but her success required the resuscitation of a career that went virtually comatose from 1997 to 2003. DeGeneres came out publicly as a lesbian on her sitcom, Ellen (1994–1998), in 1997. The show returned for one more season but was subsequently canceled. Many speculate that the final season’s poor ratings owed to network ABC’s refusal to risk alienating conservative audiences by promoting it.

Thanks largely to Ellen’s milestone pronouncement, late-1990s and early-2000s television saw a spate of LGBTQ+ characters, personalities, and plotlines. Long-running NBC sitcom Will & Grace premiered in 1998, ended in 2006, and rebooted in 2017. It features a gay male lead as well as a prominent gay supporting character. Although the show was groundbreaking and put (some) gay issues on a national stage, its characters played into many stereotypes and offered an almost exclusively white, cisgender, and normative representation of homosexuality.

Ron Becker contextualizes the 1990s spike in LGBTQ+ (mostly “G” and “L”) programming in terms of increasingly segmented markets.[17] The representation of certain safe forms of nonheterosexuality appealed to straight audiences among growing discourses of liberal tolerance. As commercial productions, the existence—or at least distribution—of film and TV shows is always to some extent a business decision. Media studios and companies are unlikely to take a chance on something they don’t believe will prove profitable. The 1990s marked a point at which many companies began to view sexual identity groups and queer-friendly audiences as viable marketing demographics. This trend continues in various venues, such as corporate Pride sponsorships, mass-market rainbow merchandise, and lifestyle networks such as LOGOtv and Here TV.

Showtime’s Queer as Folk (2000–2005) made a splash in 2000, a groundbreaking Americanization of a British series that had premiered the year before. The show, shot chiefly in Toronto, Canada, followed a group of friends and lovers through their lives in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Even though it was predominantly white, middle-class, and cismale, Queer as Folk was pioneering in terms of promoting safe sex and portraying healthful, happy characters living with HIV. The show also thematized prominent issues often associated with gay male communities, for better or for worse, such as polyamory, body dysmorphia, drug and alcohol use, and homophobic discrimination in the workplace and beyond. The L Word (2004–2009), considered by many the female version of Queer as Folk, premiered on Showtime in 2004. It achieved slightly greater diversity than its predecessor, featuring several characters of color, interracial relationships, a trans character, and a deaf character.

With a racially diverse cast, ABC’s The Fosters (2013–2018) has established long-term success among a mainstream audience for which shows such as Glee (2009–2015) and Modern Family (2009–2020) helped pave the way. The Fosters explores an array of issues specific to LGBTQ+ people, such as transitioning and bullying, as well as more universal themes related to relationships, family, and the challenges of puberty (figure 10.8). More recently, the animated series Bojack Horseman (2014–2020) broke ground with its portrayal of asexual Todd Chavez, including his coming out and navigation of ace relationships.

Artist and Activist Spotlight: RuPaul Charles

A major contemporary queer icon, RuPaul Charles (figure 10.9) gained fame in the early 1990s as a drag performer, actor, supermodel, musician, and all-around entertainer.[18] He has appeared in iconic LGBTQ+ films including Jamie Babbitt’s But I’m a Cheerleader (1999) and Beeban Kidron’s To Wong Foo, Thanks for Everything!, Julie Newmar (1995). RuPaul also produces, hosts, and judges the hit reality series RuPaul’s Drag Race, in which he mentors competitors pursuing a cash prize and the coveted title of America’s Next Drag Superstar. Although massively popular, the show’s use of offensive terms and RuPaul’s suggestion—for which he later apologized—that trans contestants possessed an unfair advantage over cis contestants have drawn criticism.

Streaming Services

Some lament the fall of the brick-and-mortar video rental store with the rise of digital video services, but the latter has proved a boon to LGBTQ+ film and television and many consumers who search for that content. The impersonality—not to say anonymity—of these platforms removed the stigma, perceived or real, that might prevent interested audiences from renting or purchasing queer movies in person. These new delivery options (and, later, streaming, a service Netflix began offering in 2007) opened veritable floodgates of viewership, especially in conservative cities, rural areas, and other environs where queer media was difficult to come by. Digital platforms such as Prime Video, Hulu, Hoopla, and Kanopy have further extended the reach of mainstream, indie, and international film, often at little or no direct cost to viewers.

Streaming and Visibility

Retail giant Amazon broke ground with Jill (now Joey) Soloway’s Transparent (2014–2019), the first show produced through Amazon Studios and aired on its streaming platform, Prime Video. Transparent follows Maura, newly out, and her family through their lives in Los Angeles. Cis actor Jeffrey Tambor won a Golden Globe for his performance in a show that presents many challenges trans populations face in society, including bathroom policing, transphobic violence, and trans-exclusionary versions of so-called feminism.

Breaking through in Jenji Kohan’s Netflix series Orange Is the New Black (2013–2019), which explores the experiences of a diverse group of women in prison, Laverne Cox (figure 10.10) has emerged as among the most prominent trans performers in the world. Her role as Sophia Burset sheds light on the particular barriers and forms of dehumanization that trans individuals face in prison, because—in addition to transphobic harassment from guards and inmates alike—their access to medically necessary materials may be curtailed.

Also on Netflix, Lena Waithe cowrote and starred in an episode, “Thanksgiving,” of Aziz Ansari’s comedy series Master of None (2015–2018, 2021). The episode, which depicts the seldom-represented experience of a Black lesbian coming out to her family, won a Primetime Emmy for Outstanding Writing for a Comedy Series.

Comedy Specials

Streaming video has also benefited comedians, providing ready access to audiences who live far from—or can’t afford—urban-centric standup circuits. The vibrancy of queer women in comedy has been a revelation for many in recent years. In addition to performers with established reputations (Rosie O’Donnell, Ellen DeGeneres, Wanda Sykes, and Margaret Cho), a new set has taken viewers by storm, thanks largely to streaming platforms. As with film and television, some LGBTQ+ comedy content expressly addresses aspects of queer identity—for example, Cameron Esposito’s viral clip about her so-called lesbian side mullet.[19] Some, such as Hannah Gadsby’s Netflix special Nanette (2018), upend the genre, critiquing misogyny and homophobia and the bound-up ways the two structure the art world, comedy, and everyday life.

Tig Notaro became famous for her standup in the mid-2010s, including a filmed set in which she lifts her shirt to reveal a chest that has undergone, as part of her breast cancer treatment, a double mastectomy. She would later write, produce, and star in One Mississippi (2015–2017), an autobiographical comedy that aired on Amazon Prime and costarred Notaro’s real-life spouse, the writer and actor Stephanie Allynne.

Other Web Content

Since the proliferation of cable options in the 1990s, the screen media market has fragmented further with the advent of the internet and the means to reach millions instantly with relatively little overhead, experience, or equipment. In 2011, the lesbian Hannah Hart (figure 10.11) broke out with My Drunk Kitchen, a YouTube comedy series whose short films parody cooking show conventions and feature Hart’s inebriated culinary ventures. Around the same time, Jazz Jennings became perhaps the youngest out trans individual to achieve national prominence in the United States. She began making media appearances at age six and later created the YouTube series I Am Jazz.[20] TLC and the Oprah Winfrey Network have produced, respectively, a reality series and a documentary about Jazz.

Multitalented queer figures such as Jes Tom (Soojung Dreams of Fiji), Fortune Feimster (Chelsea), and Sampson McCormick (A Tough Act to Follow) have been able to get around gatekeepers by producing short films available on YouTube. They gained massive followings through a combination of recorded and live performances and their social media presence. Indeed, social media platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter have created unprecedented reach and a sense of connectedness—for better or worse—for celebrities and the public. YouTube has also become a popular medium for coming out via emotionally affecting videos that sometimes accrue millions of views.

LGBTQ+ Film and Media Studies: Critical Conversations

The LGBTQ+ community is anything but monolithic, and perspectives on LGBTQ+ film and media are accordingly myriad. This section highlights some points of particular contention within the field.

Coming Out

One of the predominant tropes in LGBTQ+ film and media is the Coming Out Story, exemplified in John Sayles’s Lianna (1983), Alice Wu’s Saving Face (2004), Dee Rees’s Pariah (2011), and Greg Berlanti’s Love, Simon (2018). These films focus primarily on the protagonist’s realization or disclosure of their queerness. Sexuality is framed as a confession or disclosure, something that a closeted character hides or denies until a dramatic outing scene, often the plot’s climax. Coming out stories are important, but it is also important to challenge the status of heterosexuality as the assumed default until a different orientation is declared.

Homonormativity

Homonormativity (see chapter 1) establishes the bounds of acceptable queerness and that which deviates from it, often replicating other dominant social norms with regard to race, sex, class, and ability. For example, ABC’s popular Modern Family presents gay men (a married couple played by Jesse Tyler Ferguson and Eric Stonestreet) positively, but they are rendered respectable through other aspects of their identity: white, wealthy, monogamous, and constituents of a more or less traditionally structured nuclear family. The show’s message about queerness may therefore be read as “Look, we’re just like heterosexuals,” overriding rather than embracing difference.

Debates over homonormativity in film and television abound. For example, Glee provides numerous queer characters and storylines. Yet as Frederik Dhaenens notes, they ultimately “consolidate the heterosexual matrix” by portraying queer characters who are routinely victimized yet nonetheless overarchingly happy and conformist, as though simply rolling with the punches eventually yields contentment.[21] Moreover, LGBTQ+ people of color are still dramatically underrepresented. Gloria Calderon Kellett and Mike Royce’s web series One Day at a Time (2017–2019, 2020) follows a Latinx family and presents much-needed diversity in terms of both characters and tropes.

Bisexual Erasure

Maria San Filippo and others have critiqued bisexual erasure or invisibility within LGBTQ+ cinema. Even when bisexual themes, characters, and storylines are present in film, San Filippo observes, they are typically referred to as gay, queer, or lesbian, terms that fail to acknowledge bisexuality as its own entity.[22] Kevin Smith’s Chasing Amy (1997), Alfonso Cuarón’s Y tu mamá también (2001), David Lynch’s Mulholland Dr. (2001), Charles Herman-Wurmfeld’s Kissing Jessica Stein (2001), Ang Lee’s Brokeback Mountain (2005), and Luca Guadagnino’s Call Me by Your Name (2017) all unambiguously depict both same-sex and different-sex relationships, yet they are seldom framed in terms of bisexual identity or desire.

Ciswashing

Trans people are often excluded from mainstream (and independent) media, even from narratives specifically about trans lives. Among the films focused on trans individuals that have found commercial and critical success, many feature cisgender actors exclusively: Hilary Swank in Kimberley Peirce’s Boys Don’t Cry (1999), Felicity Huffman in Duncan Tucker’s Transamerica (2005), Jared Leto in Jean-Marc Vallée’s Dallas Buyers Club (2013), and Eddie Redmayne in Tom Hooper’s The Danish Girl (2015).

Laura Horak observes, too, that much writing on trans media focuses on representations of trans individuals rather than on trans authorship.[23] Because being out in Hollywood has always posed professional and personal risks—from pigeonholing and blacklisting to physical violence—it’s impossible to know the full extent of sexual and gender diversity that has existed among filmmakers, performers, writers, and others.

Artist and Activist Spotlight: The Wachowskis

The Wachowski siblings (figure 10.12) made history in announcing their respective transitions—Lana in 2012 and Lilly in 2016. Lana is widely considered the first major trans film director. Though most famous for their futuristic action franchise that began with The Matrix, the Wachowskis have made significant contributions in terms of queer content. Crime thriller Bound (1996) features two women who conspire in a romance-cum-heist. Wishing to avoid the cliché, pornographized, or insultingly diluted depictions of lesbian sex in film, the Wachowskis hired the sex educator and activist Susie Bright as a consultant for the sex scenes. Beyond critical success and Emmy nominations, the Wachowskis’ Netflix sci-fi series Sense8 (2015–2018) was a milestone in trans media. Created primarily by trans filmmakers and featuring a trans character played by the actress Jamie Clayton, who is trans, Sense8 offers a nuanced representation of trans lives and issues.

It Gets Better?

In 2010, the writer and activist Dan Savage and his husband, Terry Miller, founded the It Gets Better Project in response to a rash of suicides by children and teenagers subjected to homophobic bullying and harassment. The campaign entailed the launch of a YouTube channel and viral video ad featuring Savage and his family along with the message that, however tough things are at present, they will improve with time. Although the campaign brought much-needed attention to homophobia and its consequences, it also drew criticism from within the LGBTQ+ community. Many queer activists and scholars, particularly individuals of color including Jasbir Puar (2010) and Tavia Nyong’o (2010), have pointed out that Savage’s promise is predicated on a narrative of upward mobility and affluence that is unavailable to many of the most vulnerable queer populations.[24] It has also been critiqued for its failure to recognize the extent to which its makers’ racial, economic, gender-based, and physical privilege has helped clear their path. Activism and action are essential—and careful thought and reflection equally so.

Conclusion

This chapter is only a brief introduction to the wonders, shortcomings, and manifold complexities of LGBTQ+ film and media. Like raw film, it has been sliced, diced, and rearranged to fit into the narrow confines of its container. Readers who wish for more can avail themselves of the links and suggested readings and viewings that offer helpful paths to further, deeper exploration.

Profile: Giving Voice to Black Gay Men through Marlon Riggs’s Tongues Untied

Marquis Bey

Marlon Riggs, a Black gay documentarian and activist whose work was most prominent during the 1980s and early 1990s, released his classic film Tongues Untied in 1989. Riggs notes that it is a film “specifically for black gay men,” though its reception and praise has far exceeded this demographic.[25] Tongues Untied is a canonical film in the archive of Black queer cinema, along with Riggs’s other work—Ethnic Notions (1986), Color Adjustment (1991), and Black Is . . . Black Ain’t (1994). Ethnic Notions looks at racist stereotypes and caricatures of Black people in the United States; Color Adjustments surveys forty years of Black people in television; and Black Is . . . Black Ain’t explores how multifaceted Black identity is. Tongues Untied was a vanguard film because it was one of the first to explore the specificity of Black gay identity. This profile analyzes Tongues Untied as a film explicitly about Black gay identity and culture. It also meditates on Riggs’s biography and relationship to the content, marginalized voices, Black gay cultural practices, and the politics of sexuality within Black communities.

Riggs himself was in many ways the subject of his films. He was born in 1957 in Texas and grew up during the civil rights movement in the mid-twentieth century. Part of a loving family in a tight-knit Black community, Riggs was a smart, athletic, articulate child. When he graduated from high school and began college at Harvard University, he dated women while constantly trying to deny his attraction to men. For a while he tried to convince himself that men were ugly and disgusting and that loving men was vile. But eventually he conceded his sexual attractions and began living life as a Black gay man.[26] After entering into a long-term partnership with another man, he was compelled to bring his filmic talents to bear on his and others’ lives. Ultimately, Riggs felt the imperative to no longer remain silent about the plights and lives of Black gay male identity, so he took to the reel. Unlike many documentary directors at the time, he put himself in front of the camera. His films center the lives of Black people, and it was Tongues Untied that brought gay Black people to the forefront.

He brings all this to his films, and Tongues Untied can be understood as in part a representation of many things Riggs himself experienced throughout his life. Riggs was quite hesitant to make the film, remarking in an interview that

everything within me was saying, “No, no don’t do it. Find somebody else who will talk about being HIV positive. Find somebody else who will talk about being an Uncle Tom. Find somebody else who will talk about being called nigger and punk and faggot and so forth.”[27]

Amid the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the 1980s and 1990s, when many people were dying from HIV/AIDS-related illnesses (and were disproportionately Black gay men), Black queer film at the time sought to answer the questions of how to speak in the face of death and how to give voice to the dying. Even when not afflicted with deadly diseases, Black gay men lived in social conditions that were not hospitable to their flourishing. They were marked as pariahs who, even if they were HIV negative, were seen as always capable of infecting “innocent” (read: non-Black and nongay) people with their “deviant” lifestyles. The act of calling someone a faggot or nigger is an attempt to silence that person, which often worked. Many Black gay men remained fearful of expressing their sexualities because of the verbal and physical violence they could be met with. This has been occurring for too long; for too long has a racist and homophobic society disallowed Black gay men from simply living as Black gay men. So Riggs thought it absolutely necessary to break this silence.

As a film, Tongues Untied was one of the first to speak explicitly about Black gay life in ways that were not denigrating. The film features a wide range of other cultural producers of Black art, featuring the music of Billie Holiday and Nina Simone and poetry by Essex Hemphill (who also appears in the film) and Joseph Beam. It also defied categorization in its time—melding documentary, experimental filmography, poetry, and interview. Tongues Untied represented Black gay men in unconventional ways in both content and form. It depicted more than a one-dimensional image of Black gay life and conveyed not only the Black man refused entry into the gay bar because of his Blackness or the violent attack that left the gay man bleeding on the sidewalk; it also demonstrated the resilience of Black gay men, from their public protest marches in solidarity with other struggles to their intimate community, to their humorous musicology and vogue dancing (figure 10.13). All this is groundbreaking, rarely depicted filmography.

The vast majority of the film is dark. Its background is pitch black as it faces Black men speaking about their experiences. Many of the images shown are in black and white, muting colors that might have existed. The darkness of the film is symbolic of not only the Blackness of the Black men discussed but also the profound void that the imposed silence on Black gay men creates. It symbolizes isolation, loneliness, the lack of voice.

So often it is remarked that giving voice to the marginalized is important. But what does this mean? For Riggs and Tongues Untied it means “loosening the tongue,” as noted in the film. The tongue is a part of the body integral to speech, and its loosening marks a shift from voicelessness to being able to speak one’s truths. Racism and homophobia, or homophobic racism and racist homophobia, have shackled the voices of Black gay men. And their silence is and has been killing them, disallowing them to ask for things they need or to express their desires or to convey the aspects of their lives. As the Black lesbian feminist poet Audre Lorde famously said, “Your silence will not protect you.”[28] It is a silence imposed on them, so to actualize liberation it is necessary for Black gay men to reclaim their voices.

Moreover, the tongue is an instrument of pleasure and sexuality. It is used to lick, it is a key component in sucking, and it is integral to vocalizing lust and yearning. Nonheterosexual sex has been pathologized, and thus, to loosen the tongues of Black gay men gives them a voice and also allows them to express their sexual desires more freely. Riggs, in the title of his film, breaks the silence of Black gay men around sexuality and actual sexual acts.

Another prominent theme throughout is the complex culture of Black gay men. This rich complexity is showcased primarily through three practices: voguing, snapping, and responses to homophobia. Voguing is a stylized dance originating in the late 1980s and finding roots in underground ballroom scenes in the 1960s that were almost entirely queer people of color. It is inspired by the style of ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics and model poses in Vogue magazine. Voguers strike model-like poses in quick succession, integrating angular movement and holds with the arms and legs. The dance acts as a cultural site of expression in a world that routinely denies the unapologetic expression of Black and queer livelihood, thus serving as a site of catharsis among these marginalized people.

In turn, snapping is, of course, snapping one’s fingers. But this practice takes on a larger meaning in Black gay communities. Snapping is a sly yet profound retort to a number of things. The snap communicates in diverse languages and with varying connotations. It must, because Black gay men have so long been silenced. Snapping acts as a way to speak beyond conventional means; snapping is a vital communication tool for Black gay men who have been disallowed from speaking. There are a variety of different snaps, named in ways that describe their movement and purpose (e.g., classic snap, point snap). For a demographic so violently silenced, it is imperative that new forms of voice be created. Deprived of verbal voice, Black gay men can snap and say just as many things.

Encompassing these practices and the many others of Black gay communities is how the broader world treats people who are Black and gay. Riggs encapsulates this at one point in the film: a medley of different voices spew various epithets used to foreshadow and do harm to Black gay men—”punk,” “homo,” “faggot,” “motherfucking coon,” and “freak.” These are terms solely for denigrating Black and gay identity. Racist and homophobic terms such as these do more than speak badly of Black and gay people; they are themselves forms of violence. As such, these terms negatively influence how Black gay men in particular feel and behave in the world. For instance, especially in the 1980s—and still in the twenty-first century—gay men had to often hide their sexualities for fear of homophobic violence (yet still were subject to racist violence). If outed as gay, they would often be met with physical and verbal forms of harm. These violent practices led many Black gay men, and sexual minorities on the whole, to face a constant fear for their lives, unable to live publicly in affirmation of their gay identities.

To live in such constant fear necessitated an outlet. Quite often the only solace Black gay men could find during the 1980s was other Black gay men. Often, communing with other Black gay men was the only time each could be his full self. Viewers see an example of this in Tongues Untied when a group of Black gay men are sharing a meal together, sharing anecdotes about their lives. They converse about encountering homophobic vitriol, about confronting that vitriol, and about strategies used to survive in its aftermath. Such moments are life sustaining, and such moments allow for the tiny accumulation of boldness, acceptance, and love that constitute revolutionary acts.

What also weighed on Black gay men, especially during the 1980s, was how other people in the Black community forced an impossible choice, a choice described in the film as “Come the final throw-down, what is he first: Black or gay?” This is an impossible choice for Black gay men because it is impossible to separate the two identities—they are always, at the same time, Black and gay. Recognition of this is perhaps the primary lesson learned by intersectionality: that the various aspects of our identities and oppressions converge and make up one another rather than being separable into discrete categories. For example, one is Black and woman and faces bias on both of those grounds together, not one at a time. So when the revolution comes, they will be Black and gay first, because it could be no other way.

Black gay life is circumscribed by these violences, indeed, but it is not determined by them. In other words, Black gay men have a rich social life despite these violences and in the face of these violences. Riggs finds the perfect consolidation of this tension in Black gay men’s lives. Tongues Untied is, then, a film showcasing one possible way of holding on to the pain and the joy and how holding on to these two things is revolutionary. Consider what Riggs says in an interview titled “Tongues Untied Lets Loose Angry, Loving Words”:

I really spoke of black men loving black men being not just a revolutionary act, but within the context of black male dynamics, the revolutionary act. It’s not the overthrow of whitey. It’s learning to love within all the conditioning of learning to hate ourselves. To me that’s truly a radical break from our past.[29]

Revolution happens when we radically depart from the current state of things, a state of things that rests on the foundation of white supremacist and homophobic violence. In this context, Riggs is arguing that Black men loving one another is not just one revolutionary act among many others of equal weight; it is the revolutionary act. Because so much of Riggs’s world was structured by racism and homophobia, to love Black men marked a way of inhabiting the world in a profoundly revolutionary way.

It cannot be overstated how profound Black men loving Black men is, especially amid the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the 1980s when there was an underground culture of cruising—men looking for illicit, often unprotected sex with other men—during a sexual crisis. This practice affirms denigrated life. To clarify: for two Black gay men to choose one another for unprotected sex, for pure pleasure and sexual autonomy, amid the HIV/AIDS crisis is not to be reduced simply to sexual irresponsibility or, even worse, ignorance. No, it is, rather, a commitment to living one’s sexual life as fully as possible despite how much one’s very identity has been pathologized. For two Black gay men to have sex during this epidemic is an affirmation of closeness, of touch; of disregard for the various ways they have been told that their bodies and desires are disgusting and literally illegal. “I will not do what they have done to us,” the act says. “I will love every inch of you, every crevice.” And this is an unwavering love for those who have been said to be unlovable. Riggs, in giving voice to Black gay men, is voicing precisely this sentiment.

Tongues Untied remains relevant today because there is still a lack of Black gay male representation in film and media. Love between Black gay men is still a taboo topic for films, only starting to change with the acclaim a film like Moonlight (2016) received. That Tongues Untied is still one of only a few films that explicitly take up Black gay male life shows that there is still a lack of representation, which signals a larger silencing of Black gay male experience in social life. Returning to this film could reassert the importance of Black gay identity, could usher in a shift in the cultural imaginary.

All in all, the radical, revolutionary act is love, loving those who have been said to be unlovable. Tongues Untied is an ode to how breaking the silence and giving voice to the oppressed is revolutionary. So often in the 1970s Black identity and liberation was understood as one thing, by the masculinist revolutionary calls of Black Power and Black Nationalism. But Riggs’s revolution is one focused on more than just “the overthrow of whitey”; it is focused on how Black men can learn to love one another. Real transformation, at least for Riggs, is in the ending of the silence Black gay men have been forced to keep. When the silence—what is called in Tongues Untied “the deadliest weapon”—ends, perhaps Black gay men can come together and love unapologetically and openly. And as said in the opening minutes of the film, through coming together—the coming together of “BGAs: Black gay activists”—”we can make a serious revolution together.”

Profile: How One Day at a Time Avoids Negative Queer Tropes

Shyla Saltzman

Popular media, for better or worse, helps teach audiences what is valued and what is possible. Inclusive representation, or portrayals of people with diverse bodies and identities in the media, can influence how we see ourselves and feel and behave toward other people. In a Washington Post article, Amber Leventry explains that “coverage of topics and people that have historically been considered taboo can take the emotional burden off LGBTQ+ people by educating people about gender, pronouns, gender expression and sexual orientation.”[30] Studies have shown that when we see sympathetic depictions of marginalized groups, our opinions of those groups improve.[31] One study found that people are more accepting of transgender individuals after seeing them depicted onscreen, which could have positive implications for persuading the public to support policies that combat transgender discrimination.[32] Representation aids in educating, familiarizing, and also developing empathy for people we may otherwise be biased toward.

Representation is important in itself, but it needs to be handled responsibly. Reliance on reductive stereotypes or tropes can reinforce harmful messages despite the best intentions. There is more queer representation on television and in media today than ever before, which is an incredible achievement. GLAAD’s annual “Where We Are on TV” report found a larger than ever percentage of not only queer characters on network, cable, and streaming television but also queer characters of color: for the 2018–2019 TV season, 8.8 percent of regular series characters were LGBTQ+ (up from 6.4 percent), and queer characters of color outnumbered white queer characters for the first time.[33] But sometimes we celebrate too soon. LGBTQ+ visibility is important, but it is not always an advancement in and of itself. There are more queer television characters, but they are often limited to a few categories: “safe” and celibate, deeply pathologized, or otherwise preoccupied with homophobia to the detriment of their mental health and development. To consider contemporary examples of LGBTQ+ representation in media, this profile explores how the Netflix series One Day at a Time showcases nuanced queer characters in a way that offers drama, empowers queer youth, and provides learning opportunities and positive depictions for queer viewers, allies, and allies to be.

One Day at a Time focuses on a Latinx family that faces multifaceted issues and challenges. The grandmother is a devout Catholic from Cuba, and part of her narrative arc is becoming a U.S. citizen at a time when Latin American immigration is a painfully charged topic in the United States. Her daughter, Penelope Alvarez, is a single mother, as well as a war veteran who suffers from depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. Penelope struggles to become a nurse practitioner and often deals with racism and sexism in the doctor’s office where she works. Most importantly for this chapter, Penelope’s daughter, Elena, is a lesbian teenager (figure 10.14). To explain why Elena is a noteworthy lesbian character on television, we need to discuss a trope that is regularly featured in queer narratives: plot arcs that center homophobia and the calling out of bigotry.

Most shows that explore homophobia or transphobia resort to calling out for dealing with discrimination. To call someone out is to expose their problematic behavior, often in a stern way that allows onlookers to also judge them. In “Speaking Up Without Tearing Down,” Loretta J. Ross writes, “Calling out happens when we point out a mistake, not to address or rectify the damage, but instead to publicly shame the offender. In calling out, a person or group uses tactics like humiliation, shunning, scapegoating, or gossip to dominate others.”[34] The TV network Freeform has perfected the call-out scene. In their hit show Pretty Little Liars, the teenager Emily Fields has a relatively conservative mother who is horrified to learn that her daughter is lesbian. Pam Fields’s journey to acceptance begins when her husband, who fights in the U.S. military, gently chides her for judging their daughter so harshly: “I don’t like this, but [Emily] is struggling with this; I can see it. . . . She is alive and healthy, and after everything I’ve seen, alive and healthy counts for a lot, believe me.”[35] The turning point for Pam comes at an even more severe calling-out session, when multiple members of Emily’s high school English faculty confront a belligerent father who insists that Emily only won her spot on the swim team because of the school’s “gay agenda.” Pam’s moment of redemption is not, as we might hope, an embracing of Emily on her own terms or a realization that nothing has changed or broken about her daughter or their relationship; instead we get a moment of protective instinct that pits Pam against this other parent’s even more egregious form of homophobia: “My daughter never got anything she didn’t earn. That’s how we raised her. That is who she is. So you drop this . . . or I’ll show you what a real agenda is.”[36] The audience does not get to witness a substantial transformation by Pam—instead, at best, we see her realize that her daughter is subjected to a lot of pain and anger in the outside world, and she does not want to add anymore: “Emily—I still don’t understand, but I love you. You are my child, and nobody hurts my child.”[37] Before she can apologize specifically for her prejudice, Emily stops her with a hug. The gesture suggests that Pam has done enough hard work for the day and that Emily should acknowledge her for that alone.

Pam and Emily have a very moving relationship throughout the series, but Pretty Little Liars erases the discord in the family about Emily’s lesbian identity by contrasting Pam’s tortured religious homophobia with the privileged white man’s supposedly much worse homophobia. Pam saying, essentially, “My love for you and desire to protect you matters more to me than my misgivings about your sexuality,” is not the same as saying, “I am sorry that I had an unhealthy reaction that made you feel unsafe and less loved. I am your mother, and I love you the same now as I did when you were born.”

When the message is always and only “I love you more than I hate queerness,” the bar for compassion and acceptance remains very low. It magically lets family members and friends off the hook for problematic core beliefs, and it reinforces the idea that an LGBTQ+ teen’s happiness rests entirely on the benevolent epiphanies of the prejudiced people in her life. It necessitates that bigots come around before the character can have a happy ending. It also often makes the LGBTQ+ teen character take responsibility for or accept the homophobia of adults.

One Day at a Time moves away from the calling-out narrative in favor of calling in. Calling in usually involves a more sympathetic way of addressing problematic behavior: “Call-ins are agreements between people who work together to consciously help each other expand their perspectives. They encourage us to recognize our requirements for growth, to admit our mistakes and to commit to doing better.”[38] The emphasis is on educating and changing an individual, rather than shaming them. Elena’s mother, Penelope, is not on board when she first comes out as a lesbian (figure 10.15). The first refreshing and positive aspect is that the calling in is not Elena’s responsibility. In season 1, episode 11, “Pride and Prejudice,” Penelope makes every effort to support her daughter’s coming out. The audience realizes that Penelope is battling her own homophobia, but at no point does she make that Elena’s problem. Penelope notices that out of everyone in their life—her other child, a close family friend, her own mother—she is the only one struggling with Elena’s news: “I feel really weird about this Elena stuff. . . . I hate that I feel weird about it but I do.”

While Penelope is figuring out her hang-ups about her daughter’s sexuality, she knows to put on a supportive face because her “reaction could affect Elena for the rest of her life.” She turns to trustworthy adults for help. She meets with a friend, Ramona, who is an out lesbian, to talk about her reservations: “I’m a monster. My daughter came out to me and I am not totally okay with it. And I hate myself for it.” Often this sort of conversation could turn into Ramona making Penelope feel ashamed of herself or guilting her into magically getting over her homophobia because she wants to prove she is a good person. Instead, Ramona fields Penelope’s questions—“How do I know if a girl coming over is a friend or more? Does she all of a sudden think men are disgusting?”—and validates her process of coming to terms with the loss of heteronormativity in her life: “You’re just not there yet. It’s a complete adjustment in how you see your daughter. Your heart is okay; you just need a little time waiting for your [mind] to catch up.”

Aside from the inclusive coming-out narrative, Elena serves to educate audiences about queer identity and the gender binary. The first season of One Day at a Time focuses heavily on Elena’s upcoming quinceañera and how or if the occasion will reflect that she is gay. According to the website My Quince, “This coming-of-age ceremony plays an important part in preserving the heritage and cultures of the individual. Similar to the process of planning a wedding, the [quinceañera] requires the same amount of effort, time, and proper preparation in order to make the person’s birthday a memorable event.”[39] The event traditionally celebrates a teenage girl’s entering womanhood and marriageability at age fifteen—but now the family also has to reckon with Elena’s expression of womanhood not matching the underlying message and expectations of a traditional quinceañera. According to Marybel Gonzalez, “The quinceañera marks an important milestone in a girl’s life. Part birthday party, part rite of passage, it symbolizes a girl’s entrance into womanhood when turning 15, traditionally showcasing her purity and readiness for marriage.”[40] It is similar to debutante balls, a tradition of upper-class Southern white society in the United States, which signify that a teen girl has reached the age thought suitable to be married to a man. Elena’s resistance to the event’s heteronormativity manifests as concern about her dress and about the role of her relatively absent father, who is supposed to close the event with a father-daughter dance.

Elena’s grandmother happens to be a skilled seamstress and insists on making Elena’s dress; however, the grandmother’s best design does not appeal to Elena. In season 1, episode 13, “Quinces,” the grandmother confronts Elena about why she is not yet excited about her ensemble. Elena suggests, “What you’re picking up on is that I’m not really comfortable wearing a dress. . . . What about instead of heels I wear my Doc Martens?” Elena confirms that she wants a “feminist quinces” that undoes some of the heterosexist traditions. Ultimately, the grandmother redesigns the dress and reveals it to Elena the night before the quinces. The audience does not see it yet, but we know she did something important to the dress that is truer to Elena’s gender expression. When she is finally revealed at the event, we see that the grandmother eliminated the skirt portion entirely, so that now the glamorous glittering bodice of the gown is a top paired with a white suit. She is wearing masculine pants but with a generous amount of feminine sparkle.

One concession Elena makes is that she dances with a boy, presumably for the benefit of her father, who is still unhappy with Elena coming out as well as the unconventional interpretations of her quinceañera. Dancing with a boy while being dressed similarly to him actually highlights Elena’s queerness, and it is at this point that the father decides to leave the quinces and not participate in the father-daughter dance. Note that during this episode, the father’s homophobia is not centered. Beyond Penelope entreating him to show up at the quinces, no undue amount of energy is spent trying to guilt-trip the father into accepting Elena or changing his mind about LGBTQ+ identities. No one realizes he is gone until the moment the dance is supposed to start. Elena is sad to see he is gone, but that sadness could have as much to do with the familiar disappointment of being let down by her father as his homophobia. She is immediately joined on the dance floor by her mother—who is a more fitting choice in any case, since she has been the sole provider for the family. Penelope says simply, “I got you,” as she holds Elena, before they are soon joined by the closest family and friends who make up Elena’s loving support system.[41]

One Day at a Time does not present a utopia where everyone is accepted without conflict. It instead refuses to pathologize queerness or to divide the world between people who love you and people who hate you. It educates viewers on the dilemmas surrounding queer brown immigrant youth and demonstrates an alternative possibility, in which adults recognize that their bigotry is their own problem and that the happiness of a young LGBTQ+ person does not rest entirely on the acceptance of their family.

Media Attributions

- Figure 10.2. © Massimo Consoli is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 10.3. © Theredproject is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 10.5. © veritatem is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 10.6. © Jared Eberhardt is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 10.7. © Glenn Francis is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 10.9. © DVROSS is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 10.11. © Gage Skidmore is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 10.15. © Dominick D is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- J. Dry, “5 Queer Films You Didn’t Know Were Queer, from Fight Club to Showgirls,” IndieWire, July 7, 2017, https://www.indiewire.com/2017/07/best-lgbt-films-you-didnt-know-were-queer-fight-club-gay-lesbian-movies-showgirls-1201851309/. ↵

- J. Mayne, Directed by Dorothy Arzner (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994), 63. ↵

- A. Doty, Making Things Perfectly Queer: Interpreting Mass Culture (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993), xi. ↵

- R. Dyer, Now You See It (New York: Routledge, 2013), 23. ↵

- Merriam-Webster, s.v. “trope (noun),” accessed April 14, 2019, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/trope. ↵

- B. R. Rich, New Queer Cinema: The Director’s Cut (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2013), xxv. ↵

- L. J. Leff and J. L. Simmons, The Dame in the Kimono: Hollywood, Censorship, and the Production Code (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2013), 270. ↵

- R. Krafft-Ebing, Psychopathia Sexualis: With Especial Reference to the Antipathic Sexual Instinct; a Medico-forensic Study (New York: Rebman, 1906), 399. ↵

- H. M. Benshoff and S. Griffin, Queer Images: A History of Gay and Lesbian Film in America (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2006). ↵

- T. Doherty, Pre-Code Hollywood: Sex, Immorality, and Insurrection in American Cinema, 1930–1934 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999). ↵

- J. Lewis, Hollywood v. Hard Core: How the Struggle over Censorship Created the Modern Film Industry (New York: New York University Press, 2002), 304. ↵

- C. A. Noriega, “‘Something’s Missing Here!’: Homosexuality and Film Reviews during the Production Code Era, 1934–1962,” JCMS: Journal of Cinema and Media Studies 58 (2018): 20, https://doi.org/10.1353/cj.2018.0089. ↵

- V. Russo, The Celluloid Closet: Homosexuality in the Movies, rev. ed. (1981; New York: Harper and Row, 1987). ↵

- GLAAD Media Institute, “Where We Are on TV,” https://www.glaad.org/whereweareontv. ↵

- S. Sontag, Notes on “Camp” (London: Penguin, 2018). ↵

- Rich, New Queer Cinema, xv. ↵

- R. Becker, “Prime-Time Television in the Gay Nineties: Network Television, Quality Audiences, and Gay Politics,” Velvet Light Trap 42 (1998): 36–47. ↵

- RuPaul, Lettin’ It All Hang Out (New York: Hyperion, 1995). ↵

- C. Esposito, “Cameron Esposito—Woman Who Doesn’t Sleep with Men (from Same Sex Symbol),” April 6, 2014, https://youtu.be/TSJGaVuJJn8. ↵

- I Am Jazz, TLC, https://www.tlc.com/tv-shows/i-am-jazz/. ↵

- F. Dhaenens, “Teenage Queerness: Negotiating Heteronormativity in the Representation of Gay Teenagers in Glee,” Journal of Youth Studies 16, no. 3 (2013): 304–317, https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2012.718435. ↵

- M. San Filippo, The B Word: Bisexuality in Contemporary Film and Television (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2013). ↵

- L. Horak, “Tracing the History of Trans and Gender Variant Filmmakers,” Spectator 37, no. 2 (2017): 9–20. ↵

- J. Puar, “In the Wake of It Gets Better,” Guardian, November 16, 2010, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/cifamerica/2010/nov/16/wake-it-gets-better-campaign; T. Nyong’o, “School Daze,” October 1, 2010, Bully Bloggers, https://bullybloggers.wordpress.com/2010/09/30/school-daze/. ↵

- M. Riggs, “An Interview with Marlon Riggs: Tongues Untied Lets Loose Angry, Loving Words,” interview by Robert Anbian, March 1990, http://newsreel.org/guides/Riggs-Guide/Release-Print-Riggs-Interview-1990.pdf. ↵

- I Shall Not Be Removed: The Life of Marlon Riggs, directed by Karen Everett, 1996. ↵

- POV, “Tongues Untied: Filmmaker Interview with Marlon Riggs,” season 4, episode 5, PBS, July 15, 1991, https://www.pbs.org/video/pov-tongues-untied-filmmaker-interview/. ↵

- A. Lorde, “The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action,” paper delivered at the Modern Language Association’s “Lesbian and Literature Panel,” Chicago, December 28, 1977, https://electricliterature.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/silenceintoaction.pdf. ↵

- Riggs, “An Interview with Marlon Riggs.” ↵

- A. Leventry, “The Importance of Social Media When It Comes to LGBTQ Kids Feeling Seen,” Washington Post, September 19, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/2019/09/20/importance-social-media-when-it-comes-lgbtq-kids-feeling-seen/. ↵

- See, for example, E. Schiappa, P. B. Gregg, and D. E. Hewes, “The Parasocial Contact Hypothesis,” Communication Monographs 72, no. 1 (2005): 92–115. ↵

- A. R. Flores, D. P. Haider-Markel, D. C. Lewis, P. R. Miller, B. L. Tadlock, and J. K. Taylor, “Transgender Prejudice Reduction and Opinions on Transgender Rights: Results from a Mediation Analysis on Experimental Data,” Research and Politics 5, no. 1 (2018), https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168018764945. ↵

- R. Deerwater, “Color of Change, Women’s Media Center, RespectAbility, NHMC React to GLAAD’s ‘Where We Are on TV’ Findings,” GLAAD, October 30, 2018, https://www.glaad.org/blog/color-change-women%E2%80%99s-media-center-respectability-nhmc-react-glaad%E2%80%99s-%E2%80%98where-we-are-tv%E2%80%99-findings. ↵

- L. J. Ross, “Speaking Up Without Tearing Down,” Teaching Tolerance, no. 61 (2019), https://www.tolerance.org/magazine/spring-2019/speaking-up-without-tearing-down. ↵

- N. Buckley, dir., “Moments Later,” season 1, episode 11, Pretty Little Liars, January 3, 2011. ↵

- M. Grossman, dir., “The New Normal,” season 1, episode 17, Pretty Little Liars, February 14, 2011. ↵

- Grossman, “The New Normal.” ↵

- Ross, “Speaking Up Without Tearing Down.” ↵

- “What Is a Quinceañera and Why Is It So Important?,” My Quince, accessed July 23, 2015, https://www.myquincemagazine.com/what-is-a-quinceanera-and-why-is-it-so-important/. ↵

- M. Gonzalez, “The Quinceañera, a Rite of Passage in Transition,” New York Times, June 4, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/05/nyregion/the-quinceanera-a-rite-of-passage-in-transition.html. ↵

- P. Fryman, dir., “Quinces,” season 1, episode 13, One Day at a Time, June 4, 2016. ↵

Pertaining to a person or group that does not fall within the gender binary of heterosexuality.

Portrayal of a person or group by a representative who acts for them or in their interests.

The way a story is told, including choices such as editing, cinematography, wardrobe, and framing.

The substance of a story, typically entailing narrative, characters, and dialogue.

A pattern, phrase, rhetorical device, or plot point that has been used so often it can be categorized and anticipated.

Fear or hatred for queerness and queer people.

Representing a trait, behavior, or identity as a sickness or inevitable tragedy.

An aesthetic that privileges poor taste, shock value, and irony and poses an intentional challenge to the traditional attributes of high art. It is often characterized by showiness, extreme artifice, and tackiness.

An asexual person is known as ace, and they have asexual relationships.

A political and sometimes narrative approach that works to establish LGBTQ+ lives as no different from straight lives beyond the genders one is attracted to. It is an assimilation-based approach that invokes the rhetoric of sameness in appeals for civil rights and social acceptance.

To be rendered less important, less powerful, and less visible than what is considered the norm or mainstream.

Containing layers of meaning, having subtle differences.

Approaching problematic behavior or language combatively; striving to shame a group or individual for their behavior to serve as a warning to others.

A preconceived positive or (usually) negative feeling toward someone or something.

Receiving advantages that are not available to everyone.

Approaching problematic behavior or language with sympathy; asking why the behavior occurred, explaining why it is oppressive, and devising a new course of action collaboratively.

Policies, beliefs, and behaviors that assume everyone adheres to the gender binary, or that everyone is heterosexual.

The idea that there are only two genders, male and female, and that everyone should and will identify accordingly.

Policies, beliefs, or behaviors enacted by straight people that discriminate against queer people.

The external presentation of gender, through body language, pronoun choice, and style of dress.

Intolerance or bias toward an identity or group of people.