Private: Part I: Theoretical Foundations

Chapter 1: Thirty Years of Queer Theory

Jennifer Miller

Introduction

It is a challenge to create an origin story about a field of study, in this instance queer theory, because ideas are not birthed in a moment, a day, or even a year. They build on what has come before, reflect on it, challenge it, seek to bend or break it, and only eventually, and only sometimes, become an identifiable entity with a name given to them. The story of queer theory’s emergence is entwined with queer activism. Queer theory and queer activism are products of their historical moment as well as transformative forces changing how gender and sexuality are understood in multiple academic disciplines and, increasingly, outside academia. Additionally, both queer theory and activism introduced ways of thinking and acting through politics that went beyond normalizing demands for the inclusion of LGBTQ+ people in existing social institutions.

The 1970s and 1980s saw a rapid increase in lesbian and gay activism and scholarship. A police raid at the Stonewall Inn in New York City in 1969 ignited demonstrations. Following the Stonewall rebellion, lesbian and gay liberation groups started to fight for equal rights, and some scholars started to study the history and culture of lesbians, gays, and bisexuals. Then, in 1987, Larry Kramer, Vito Russo, and others founded the direct-action group AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) to demand that politicians, the medical community, drug manufacturers, and the public acknowledge the AIDS epidemic. The group’s motto was, and remains, “Silence = Death.”[1] An offshoot of ACT UP, Queer Nation, was founded in 1990 to fight the escalating violence and discrimination against LGBTQ+ people.

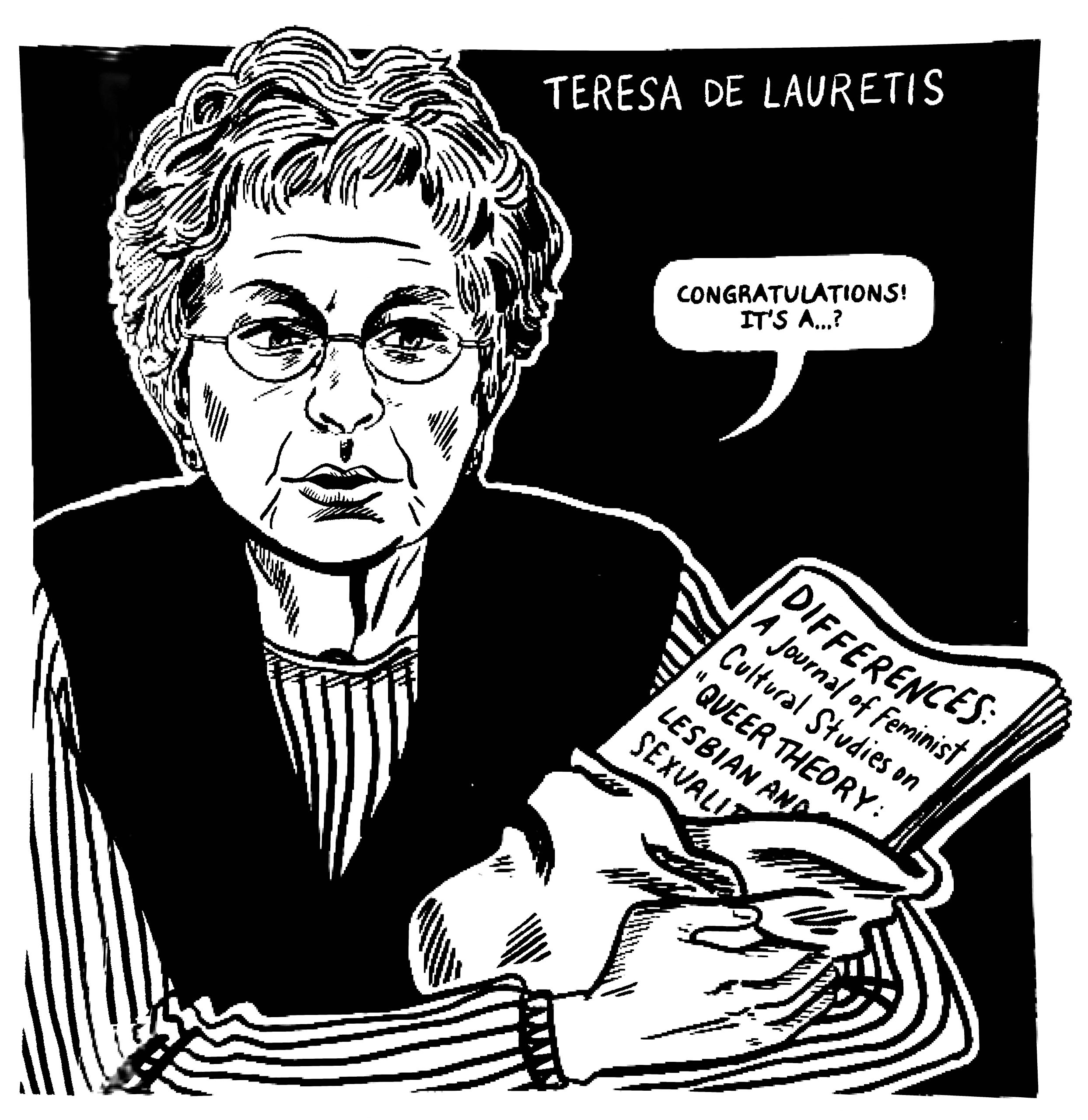

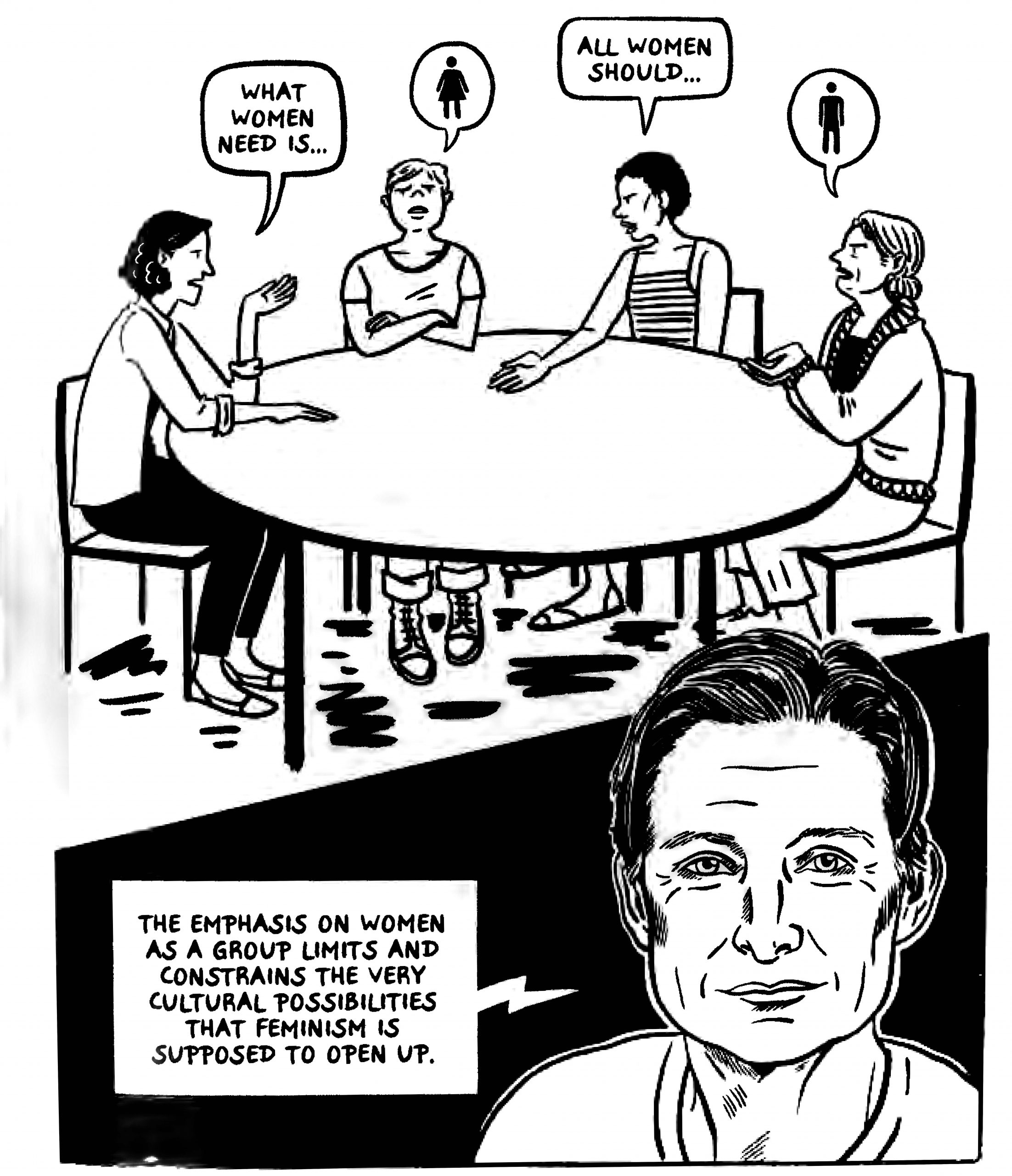

At roughly the same time, the term queer theory began to circulate and quickly gained momentum within academic circles. The film theorist Teresa de Lauretis (figure 1.1) coined the term at a University of California, Santa Cruz, conference about lesbian and gay sexualities in February 1990. The conference proceedings were later collected in a 1991 special issue of Differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies. In her introduction to the special issue, de Lauretis outlines the central features of queer theory, sketching the field in broad strokes that have held up remarkably well.[2]

De Lauretis suggested gay and lesbian sexualities should be studied, not as deviations of heterosexuality, but on their own terms. She went on to claim gay and lesbian sexualities should be “understood and imagined as forms of resistance to cultural homogenization, counteracting dominant discourses.”[3] According to de Lauretis, and queer theorists more generally, lesbian and gay sexualities enact nonnormative intimate and social modes of relating; they put new things in the world, and those new things have transformative potential.

From its earliest iterations, queer theory challenged norms that reproduced inequalities and, at its best, sought to understand how sexuality intersected with gender, race, class, and other social identities to maintain social hierarchies. In fact, de Lauretis used the term queer to create critical distance from lesbian and gay studies. Lesbian and gay studies courses began to appear in the 1970s, and programs slowly emerged in the 1980s. De Lauretis claimed that differences were collapsed within lesbian and gay studies and the experience of white middle-class gay men was privileged. She notes that although it became standard to refer to lesbians and gays in the 1980s, the “and” obscured differences instead of revealing them.[4] In addition to sexuality, de Lauretis hoped queer theory would identify and trouble other “constructed silences”—for instance, those of race, ethnicity, class, and gender.[5] She wanted to break with the past and transform the future by developing new ways of conceptualizing sexual identities in the present of the 1990s.

Gay and lesbian activism has a complex history in the United States and even more so globally. Activist demands that have been most palatable to cisgender heterosexuals are those that foreground the right to privacy, individual autonomy, and equal access to social institutions like marriage and the military. However, queer activism and scholarship reject mainstream liberal ideals of privacy, the goal of formal equality under the law, and the desirability of assimilation into existing social institutions. Instead, queer theory and activism demand publicness, reject civility, and challenge the legitimacy, naturalness, and intrinsic value of institutions—whether marriage or the military—that regulate gender and sexuality.[6] Of course, this very critical, very radical relationship to the normative appears in times before the late 1980s and in places other than the United States, but it is then and there that queer activism and queer theory are named and begin to be, however hesitantly, defined.

This chapter explores the development of queer theory from the 1990s to the present. It begins by elaborating on distinctions between gay and lesbian studies and queer studies before identifying important trends in queer theory.

The Constructionist Turn in Sexuality and Gender Studies

Lesbian and gay studies assumed clear subjects of analysis—lesbians and gays—who were studied as historical, cultural, or literary figures of significance to reclaim a forgotten past and create a sense of collective identity and continuity in the present. Some would argue that lesbian and gay studies took an essentialist view of sexuality that assumed individuals possessed a fixed and innate sexual identity that was both universal and transhistorical.[7]

Queer theorists take a very different approach to understanding identity, which can be understood as constructionist. Constructionists see identity as a sociocultural construct that changes. To assert that identities are sociocultural constructs assumes that in different times and places different meanings and values dominate and influence identity. These meanings and values are transmitted through cultural texts like television, music, or film and are produced within social institutions like schools, museums, and families. As a result, meanings and values change across space and time.

In the mid-1970s, the French historian and philosopher Michel Foucault published The History of Sexuality, which describes the origin of modern homosexual identity. In this sweeping history of sexuality, Foucault creates an influential theory of sexual-identity formation. For Foucault, “Sexuality must not be thought of as a kind of natural given which power tries to hold in check, or as an obscure domain which knowledge tries gradually to uncover. It is the name that can be given to a historical construct.”[8] By rejecting the idea that something called sexuality exists in all of us, waiting to be liberated, Foucault’s work challenged not only how sexuality was understood in popular and scholarly discourses but also how power was understood. For Foucault, power does not repress a preexisting sexual identity; it provides the conditions needed for sexual identities to multiply. Here it is important to distinguish between sexual identities and sexual practices. Sexual practices have existed in multiple forms across time and space, but only in particular moments do practices congeal into identities that can be named and managed.

According to Foucault, power is everywhere, although it is not evenly dispersed. He argues that medical discourse, particularly the field of sexology, which applies scientific principles to the study of sexuality, intersected with legal discourse to simultaneously create the need and the means to identify and produce knowledge about sexual identity, particularly “the homosexual.” Power in this instance belonged to medical and legal authorities. However, naming the homosexual had unforeseen consequences. Those identified as homosexual in medical discourse appropriated the discourse to revise what the category might mean, identify one another, build a community, and make political demands. This can be seen in the early homophile movement, which refers to late nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century homosexual rights activism that emerged in tandem and entwined with sexology and anti-sodomy laws.

Foucault’s work influenced a new wave of historians committed to studying the construction of modern homosexuality. David Halperin, a historian of classical Greek culture, provided volumes’ worth of historical evidence to support Foucault’s more theoretical claims.[9] Halperin argues that using modern identity frameworks to understand culturally and historically specific expressions of desire is poor scholarship. He interprets sexual histories through a queer lens that does not assume that identities and experiences are universal. John D’Emilio, another queer historian, connects the development of modern gay identity to nineteenth-century urbanization and industrialization.[10] Jonathan Ned Katz, also a historian, focuses a critically queer lens on heterosexuality, arguing that it is also a social construct.[11] By demonstrating that heterosexuality, like homosexuality, is a modern invention, Katz seeks to strip the category of its normalizing power.

Foucault, Halperin, D’Emilio, and Katz contribute to a critical understanding of the social construction of homosexuality and heterosexuality. This does important political and intellectual work in troubling the idea of heterosexuality as normal and natural, a claim that has been used to marginalize homosexuals.

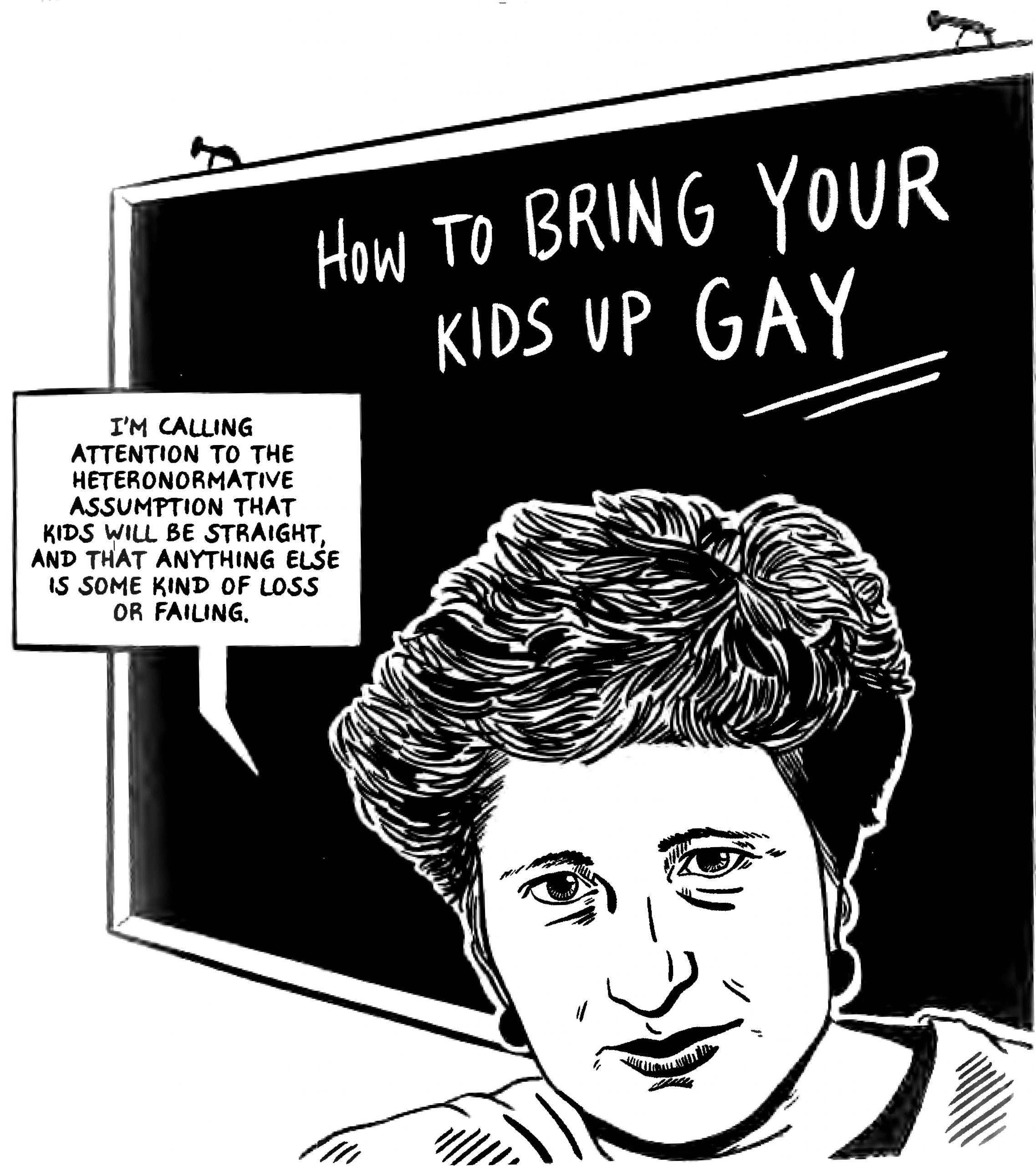

Eve Sedgwick, a literary theorist, continues the project of troubling both homosexuality and heterosexuality in her 1990 publication Epistemology of the Closet, which is widely recognized as a foundational queer theory text (figure 1.2). Sedgwick argues that by the twentieth century, in Western culture, every person was assigned a sexual identity.[12] For Sedgwick, the history of homosexuality is not a minority history—it is the history of modern Western culture. According to Sedgwick, homosexual and heterosexual definition is central to the construction of the modern nation-state, because it informs modern modes of population management. She introduces the terms minoritizing and universalizing to describe competing and coexisting understandings of homosexuality that shape how we imagine sexuality.

The minoritizing view sees homosexuality as relevant only to homosexuals. This view sees homosexuals as a specific group of people, a minority, within a largely heterosexual world. This can have its uses—for instance, in creating a discernible community able to make demands of the state, as seen in the homophile movement as well as in current gay (and lesbian) rights activism. The universalizing view, in contrast, sees sexuality and sexual definition as important to everyone. This is the position Sedgwick takes in her book when she claims that sexual definition is central to social organization and identity formation.

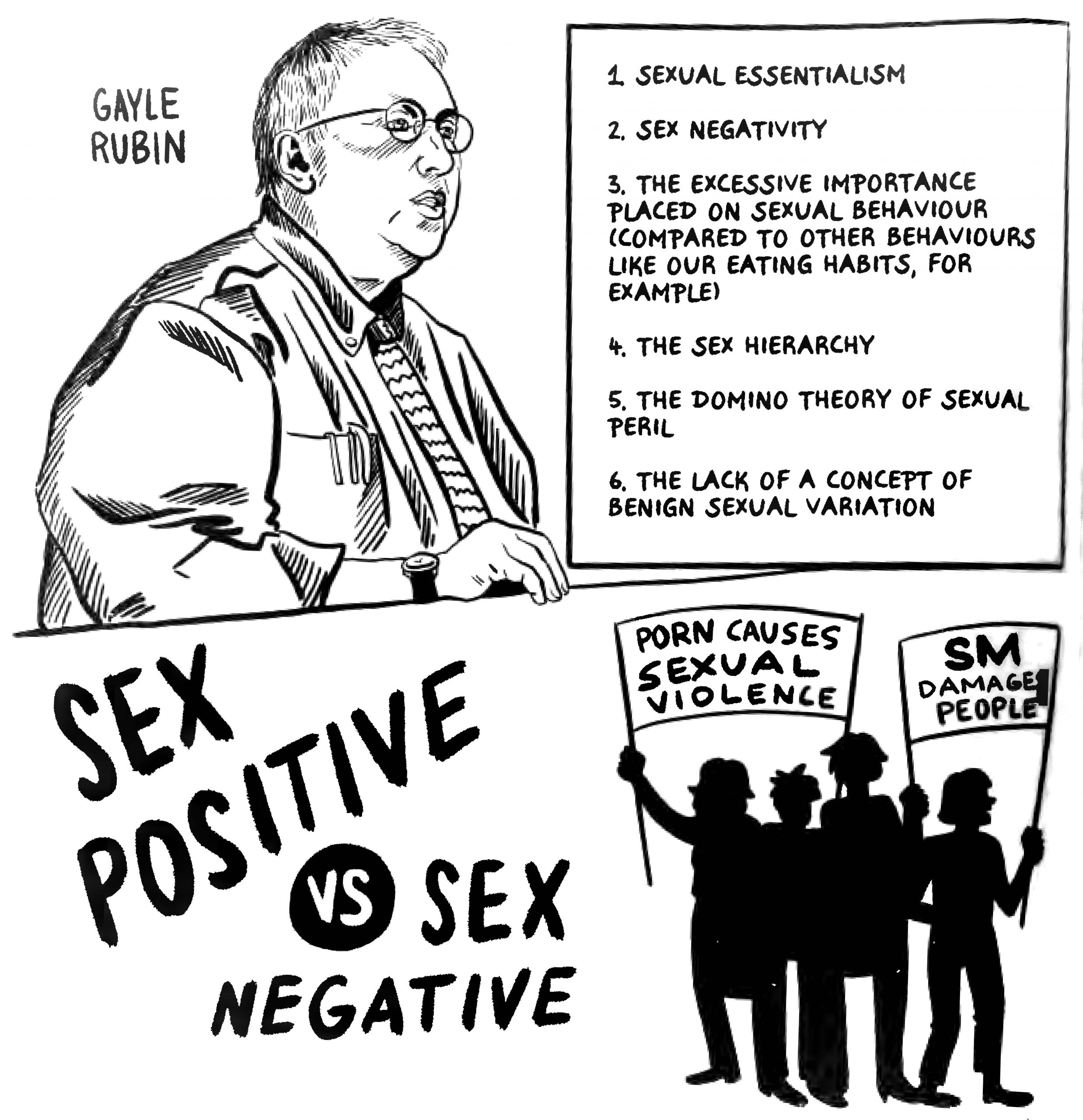

Social constructionism also influenced understandings of gender. For instance, the cultural anthropologist Gayle Rubin’s essay “The Traffic in Women: Notes on the ‘Political Economy’ of Sex” sought to identify the origin of women’s oppression across cultures.[13] It is a constructivist account of gender identity that connects the binary construction of gender (man or woman) to heterosexual kinship and by extension to women’s oppression within heterosexual patriarchal cultures (figure 1.3).

Rubin uses the phrase sex-gender system to describe the process by which social relations produce women as oppressed beings. According to Rubin, “One begins to have a sense of a systematic social apparatus which takes up females as raw material and fashions domesticated women as products.”[14] Rubin writes, “As a preliminary definition, a ‘ sex-gender system’ is the set of arrangements by which a society transforms biological sexuality into products of human activity and in which these transformed sexual needs are satisfied.”[15]

Although Rubin’s work is very influential in feminist and queer theory, one of her basic assumptions, that sex is raw material and thus lacks the influence of social norms, has been challenged by other queer theorists.

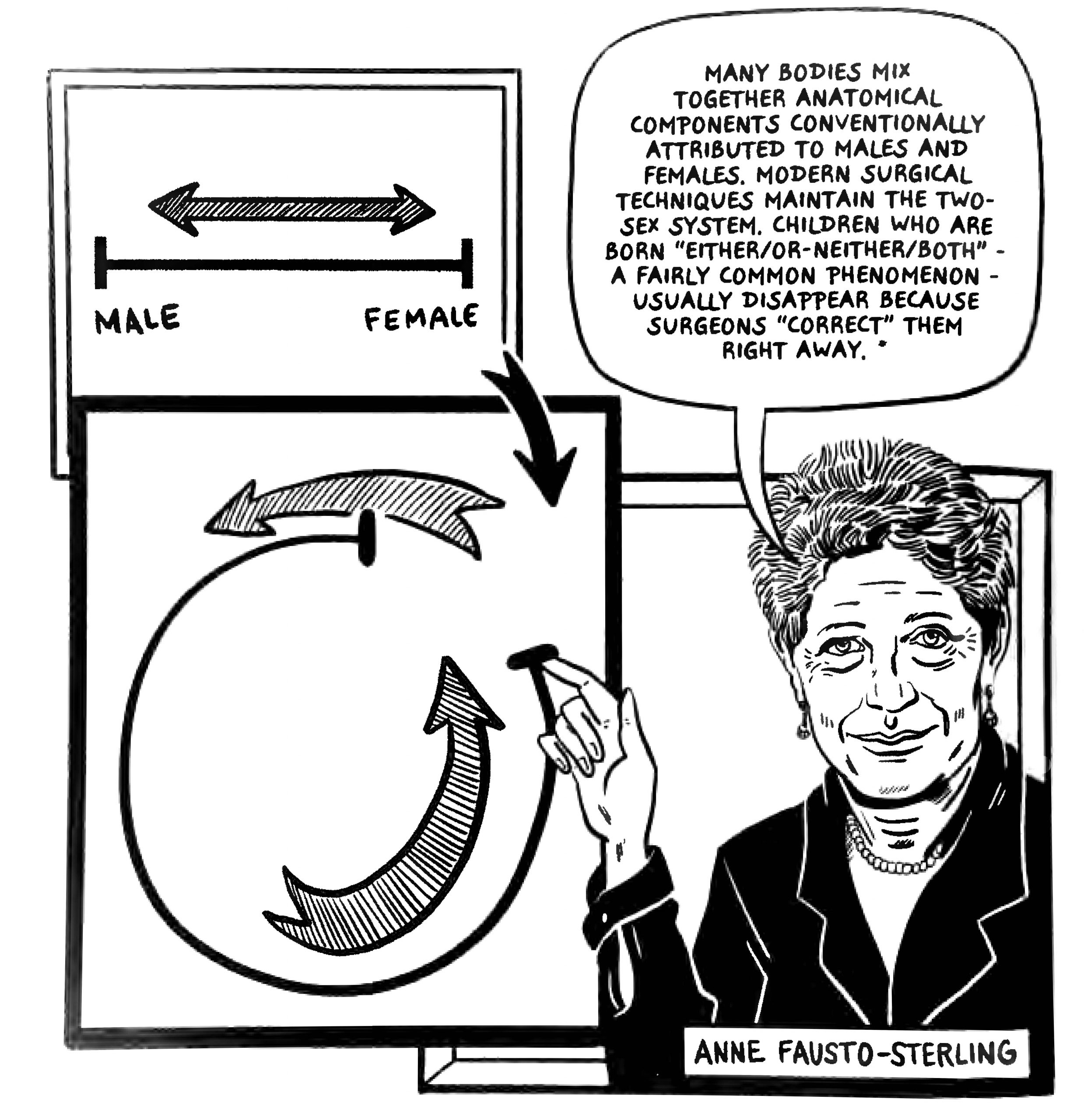

The queer feminist science scholar Anne Fausto-Sterling’s early 1990s work on intersex categories contends that although social institutions are invested in maintaining a dyadic sex system, this system does not map onto nature (figure 1.4). She argues that sex exists as a spectrum between female and male with a minimum of five distinct categories. Fausto-Sterling introduces the terms “herms,” “ferms,” and “merms” to categorize anatomical, hormonal, and chromosomal differences that fall outside a male-female sex dyad.[16] Like Rubin, Fausto-Sterling’s early provocation about sex categories sees sex as biological, natural, and unchangeable; it is raw material that culture transforms into gender. Both Rubin’s work and Fausto-Sterling’s early work leave a nature-nurture binary in place and suggest that sex correlates with nature and gender correlates with nurture.

Fausto-Sterling’s work was soon challenged for focusing too much attention on genitals. For instance, the social psychologist Suzanne Kessler was critical of Fausto-Sterling’s attachment to reading genitals for the truth of sex, insisting that the performance of gender on the body rather than on genitalia was more often used to gender bodies.[17] Fausto-Sterling has since conceded Kessler’s point.[18] Most queer theoretical engagements with gender deprivilege the body, particularly genitals, as a site of truth by suggesting that the appearance of binary sexed bodies is actually an effect of binary gender discourse and, as discussed in the next section, binary performances of gender. In other words, a binary sex-gender system that assumes a correlation between sex and gender is an effect of power, not nature.

Gender Performativity

The cultural anthropologist Esther Newton published Mother Camp: Female Impersonators in America, a groundbreaking ethnography of drag culture in 1972. Newton uses the term drag queen to describe a “homosexual male who often, or habitually, dresses in female attire.”[19] Newton separated the sexed body from the gender expressed on it, suggesting that there is no natural link between the two, as discussed in the previous section, but in 1972 the link between sex and gender remained tightly clamped. Newton writes, “The effect of the drag system is to wrench sex roles loose from that which supposedly determines them, that is, genital sex. Gay people know that sex-typed behavior can be achieved, contrary to what is popularly believed. They know that the possession of one type of genital equipment by no means guarantees the ‘naturally appropriate’ behavior.”[20]

Like Rubin, Newton was writing before the 1990 birth of queer theory. Also like Rubin, her intellectual investments and theoretical findings were harbingers of things to come. In fact, Judith Butler, who is often identified as an early and formative player in the creation of queer theory, cites both theorists as influential to her work on performativity.

Judith Butler’s Gender Trouble, originally published in 1990, introduces the term performativity to suggest that gender identity is not natural and does not emanate from an essential truth that can be located on or in the body (figure 1.5). For Butler, gender is established as consistent and cohesive through its repeated performance.[21] Importantly, for Butler, because gender must be constantly reperformed, it can be intentionally or unintentionally troubled, revealing it as an ongoing project with no origin. This is similar to Newton’s observation of drag, particularly her suggestion that drag reveals gender as a performance.

Gender Trouble was critiqued for ignoring the materiality of the body and real sex differences. In a follow-up publication, Butler argues that sex is a regulatory ideal that forces many bodies into a two-part system.[22] This is likely reminiscent of Fausto-Sterling’s provocation that there are five discernible sexes. Butler responded to critique by arguing that, although discourse does not produce material sex differences, it organizes these differences, gives them meaning, and renders them legible.[23]

In Female Masculinity, Jack Halberstam continues the work of disentangling gender from genitals through a series of interpretive readings of literary, filmic, and historical representations (figure 1.6). Halberstam argues that female masculinity “actually affords us a glimpse of how masculinity is constructed as masculinity.”[24] In other words, women and especially lesbians who are masculine reveal masculinity as a construct, in much the same way that drag queen performances reveal femininity as a construct. Halberstam convincingly claims, “Masculinity must not and cannot and should not reduce down to the male body and its effects.”[25] Like many queer theorists engaging gender, Halberstam deemphasizes genitals, refocusing on gender expressions. In other words, much as Newton observes about drag performances of femininity, anybody can put on a gender expression.

Queer theories of gender have influenced scholars across disciplines, radically transforming how we think about gender. For Butler, there is no natural and essential gender or sexuality that queers deviate from. For Newton, femininity is not the property of women, just as for Halberstam masculinity is not the property of men. Instead, we are all citing, at times contesting, at others complying with, existing ideas about gender and sexuality. Additionally, these ideas, and the value hierarchies that adhere to them, are maintained only by their reproduction.

The work discussed in this chapter dissipates some of the power that coheres around the idea of natural gender and sexuality, an idea that has often been used to mark queer genders and sexualities as unnatural and by extension inferior to heterosexuality.

Transgender Studies

Transgender studies is an interdisciplinary field of knowledge production that, like queer theory, challenges discursive and institutional regimes of normativity. However, whereas queer theory is sometimes guilty of the “privileging of homosexual ways of differing from heterosexual norms,” transgender studies challenges naturalized links between the material body, psychic structures, and gendered social roles.[26] Transgender studies emerged in activist and academic circles around the same time as queer activism and theory. The anthropologist David Valentine attributes the term’s early emergence to activist communities in the United States and the United Kingdom, noting that “it was seen as a way of organizing a politics of gender variance that differentiated it from homosexuality.”[27]

Susan Stryker provides an even more specific periodization, finding that the term transgender emerged in the 1980s but didn’t take on its current meaning until 1992 when Leslie Feinberg published Transgender Liberation: A Movement Whose Time Has Come.[28] At this point transgender began to be used broadly to refer to “discomfort with role expectations, being queer, occasional or more frequent cross-dressing, permanent cross-dressing and cross-gender living, through to accessing major health interventions such as hormonal therapy and surgical reassignment procedures.”[29] Before the 1990s, transgender referred specifically to persons who socially transitioned to a gender other than the one they were assigned at birth without using hormones or surgery to medically transition.

By refusing to accept that there is a right way to be transgender and encouraging coalition building under the newly flexible term transgender, Feinberg hoped transgender persons could build a transformative activism-oriented community.[30] Feinberg’s 1993 publication, Stone Butch Blues, is a fictionalized personal account of negotiating New York City as a butch lesbian in the 1970s.[31] Feinberg experienced harassment and brutality at the hands of police, and the vivid descriptions of violence in the book illustrate the consequences of not embodying a socially sanctioned gender expression. Work like this and work published by other trans scholars demonstrates the importance of thinking gender and sexuality queerly.

Another example is Kate Bornstein, whose 1995 publication, Gender Outlaw: On Men, Women, and the Rest of Us, humorously and accessibly describes her experiences with gender and sexuality.[32] Bornstein writes, “I identify as neither male nor female, and now that my lover is going through his gender change, it turns out I’m neither straight nor gay.”[33] She matter-of-factly expresses her feelings of shame at not fitting into normative gender identities and a corresponding sense of relief with intellectual work coming out in the 1990s that made it possible to understand gender as a social construct.[34]

Against Normativity

In the first years of the 2000s, groups like the Human Rights Campaign (HRC), which takes a formal rights approach to securing legal protections for LGBTQ+ persons, experienced many successes.[35] For instance, Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell, a policy of forced silence about sexuality for gay, lesbian, and bisexual service members instituted by the Bill Clinton administration in 1993, was repealed in 2011. Additionally, as of June 26, 2015, same-sex marriage is legal in the United States. Although inclusion in these institutions is contingent, precarious, and not evenly distributed among all members of the LGBTQ+ community, these two shifts in policy secured access and rights for some LGBTQ+ persons—specifically, white middle-class gay men for whom marriage equality has often been a primary political concern.

Queer critics of the HRC maintain that the organization has a limited vision of human rights, is procapitalist, and supports bills that fail to include transgender persons—for example, the proposed 2007 Employment Non-discrimination Act. For queers invested in transformative justice-oriented politics, the assimilationist strategies employed by liberal LGBTQ+ organizations typified by the HRC stand in the way of meaningful social change. Many queer theorists and activists are concerned that emphasizing single issues (marriage or the military) and centering LGBTQ+ politics on inclusion into existing institutions diminishes the radical potential of queer thought and action. The desire for radical social change that is central to the queer theoretical project is discussed further in the next section.

Lisa Duggan coined the term homonormativity to describe the activist work of groups like the HRC.[36]. According to Duggan, groups like the HRC represent the interests of white middle-class gay men whose privilege provides them cover to access social institutions and benefit from assimilation in ways unavailable or undesirable to other members of the LGBTQ+ community. For instance, a primary benefit of marriage is access to health insurance, but one partner must have health insurance for marriage to help a couple in this way. Job discrimination, housing discrimination, street harassment, and access to identification documents are central to the politics of queers of color as well as women and lower-income members of the LGBTQ+ community. Many express criticism that groups like the HRC have become representative voices of the LGBTQ+ community and are failing to represent its most vulnerable members.

Published only a few years after Duggan’s work on homonormativity and neoliberalism, Jasbir Puar’s Terrorist Assemblages: Homonationalism in Queer Times confirms that some queer subjects have been incorporated into U.S. national life as valued citizens. However, according to Puar, “This benevolence towards sexual others is contingent upon ever-narrowing parameters of white racial privilege, consumption capabilities, gender and kinship normativity, and bodily integrity.”[37] Puar further argues that welcoming some queers into national life requires queerness to be projected onto other bodies. She suggests that the deviancy and abjection previously associated with gay and lesbian sexualities is redirected to brown Muslim bodies and instrumentalized to justify the war on terror. That is, the United States appeals to its tolerance of some queers to construct itself as civil and progressive. It then attaches sexual backwardness and violent homophobia to Islamic nations.

Duggan and Puar are critical of activist initiatives that are based on inclusion into existing social institutions, because they see these institutions themselves as damaging. Furthermore, they argue that capitalism and militarism do harm and can only contingently benefit individual LGBTQ+ persons.

Queer Politics, Transformative Politics

Queer theorists like Duggan and Puar are critical of assimilationist politics, but neither offers tangible suggestions for what a socially just and queer-inclusive world might look like. Other queer theorists, particularly queer of color theorists, are doing the important work of imagining politics and society radically differently. Their scholarship gestures toward what a queerly transformed world might look like.

José Esteban Muñoz’s hope-affirming work claims the future for queers (figure 1.7). He writes, “The future is queerness’s domain. Queerness is a structuring and educated mode of desiring that allows us to see and feel beyond the quagmire of the present.”[38] For Muñoz, conditions of everyday life are simply not viable for queer people of color, which prompts many to imagine a transformed world. In Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity, Muñoz explores “the critical imagination,” which he refers to as transformative thought that can prompt and shape social change. This idea, along with Muñoz’s intersectional theorization of oppression and social transformation, resonates with many other queer theorists.[39]

The activist Charlene A. Carruthers’s Unapologetic: A Black, Queer, and Feminist Mandate for Radical Movements foregrounds the importance of intersectional thinking. She introduces a “Black queer feminist lens,” which she describes as a lens “through which people and groups see to bring their full selves into the process of dismantling all systems of oppression.”[40] Whereas libertarian, conservative, and even liberal lesbian and gay groups seek to diminish the importance of sexual (and other) differences, Carruthers suggests that bringing a Black queer feminist lens to political thought and praxis renounces the middle-class notion of the public sphere as a place where identity should be abandoned to maintain the myth of universality.[41] Even more, her vision of activism decenters queerness; she demands that multiple types of oppression, types that will not be experienced the same way or even at all by the entire LGBTQ+ community, must be acknowledged to imagine and enact a truly transformed, justice-oriented social world.

Like Muñoz, Carruthers emphasizes the importance of the Black imagination, specifically the ability to imagine “alternative economics, alternative family structures, or something else entirely.”[42] This work cannot be accomplished if groups like the HRC, which has a clear procapitalist agenda, shape public discourse about LGBTQ+ issues.

In After the Party: A Manifesto for Queer of Color Life, Joshua Chambers-Letson explores the affect music and art can have on audiences in an attempt to theorize the conditions necessary to envision collective change. He suggests that creative work can expand imaginative possibilities and prompt new modes of being together in the world. His project explores “the ways minoritarian subjects mobilize performance to survive the present, improvise new worlds, and sustain new ways of being in the world.”[43]

Similar to Muñoz and Carruthers, he argues that radical transformation is the only way forward for queers of color. Instead of asking, How can we include queers in the existing social world, he asks, How can we queer the existing social world to make it habitable by queers?

Additionally, like Carruthers, Chambers-Letson decenters the queer sexual subject and queer theory to explore intersectional possibilities for speculative world making and practical activism. For him, experiencing performance allows audiences to rehearse new ways of seeing and being in the world together, which is why he emphasizes the importance of art and music. Importantly, Chambers-Letson does not see art and performance as able to fulfill the promise of revolutionary transformative change; instead, it is a site where possible worlds are imagined, but they must still be materially enacted.[44]

Conclusion

This chapter maps the emergence of queer theory, over time and across disciplines, out of the lived experiences of diverse LGBTQ+ people. Both activism and theory are historically and geographically contingent, tethered to time, space, and the material body in its specificity. Queer theory is flexible enough to account for differences of race, class, gender, and nation, although it does not always do so. It does, however, have at its founding, and through the twists and turns of its development, an investment in radical social change tethered to a belief that, because gender, sexual, and other forms of social hierarchy are reproduced and regulated through discourse and social institutions, those institutions can and must be changed for the better.

Media Attributions

- Figure 1.8. © The Root / BYP 100 is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- ACT UP New York (website), accessed March 8, 2021, https://actupny.com/. ↵

- T. de Lauretis, “Queer Theory: Lesbian and Gay Sexualities,” in special issue, Differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies 3, no. 2 (1991): iii. ↵

- De Lauretis, iii. ↵

- De Lauretis, vi. ↵

- De Lauretis, iv. ↵

- L. Duggan, “Making It Perfectly Queer,” in Theorizing Feminism Parallel Trends in the Humanities and Social Sciences, ed. Anne C. Herrmann and Abigail J. Stewart (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2001), 219. ↵

- A. Jagose, Queer Theory: An Introduction (New York: New York University Press, 1997), 8; Duggan, “Making It Perfectly Queer,” 225. ↵

- M. Foucault, The History of Sexuality, vol. 1, An Introduction, trans. Robert Hurley (New York: Vintage, 1990), 23. ↵

- D. Halperin, One Hundred Years of Homosexuality: And Other Essays on Greek Love, illustrated edition (New York: Routledge, 1989); David Halperin, How to Do the History of Homosexuality (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002). ↵

- J. D’Emilio, “Capitalism and Gay Identity,” in The Gender/Sexuality Reader: Culture, History, Political Economy, ed. Roger N. Lancaster and Micaela di Leonardo (New York: Routledge, 1997), 169–178. ↵

- J. Ned Katz, “The Invention of Heterosexuality,” Socialist Review 20 (March 1990): 7–34. ↵

- E. Kosofsky Sedgwick, Epistemology of the Closet, 2nd ed. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008), 1. ↵

- G. Rubin, “The Traffic in Women: Notes on the ‘Political Economy’ of Sex,” in Women, Class and the Feminist Imagination, ed. Karen V. Hansen and Ilene J. Philipson (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1990), 74–112. ↵

- Rubin, “The Traffic in Women,” 78. ↵

- Rubin, 79. ↵

- A. Fausto-Sterling, “The Five Sexes: Why Male and Female Are Not Enough,” Sciences 33, no. 2 (March–April 1993): 20–24. ↵

- S. J. Kessler, Lessons from the Intersexed (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1998). ↵

- A. Fausto-Sterling, “The Five Sexes, Revisited,” Sciences 40, no. 4 (July–August 2000): 18–23. ↵

- E. Newton, Mother Camp: Female Impersonators in America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1979), 100. ↵

- Newton, Mother Camp, 103. ↵

- J. Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (New York: Routledge, 2006). ↵

- J. Butler, Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of Sex (New York: Routledge, 1993). ↵

- Butler, Bodies That Matter. ↵

- J. “Jack” Halberstam, Female Masculinity (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1998), 1. ↵

- Halberstam, 1. ↵

- S. Stryker, “(De)Subjugated Knowledges: An Introduction to Transgender Studies,” in The Transgender Studies Reader, ed. Susan Stryker (London: Routledge, 2006), 7. ↵

- D. Valentine, Imagining Transgender: An Ethnography of a Category (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007), 33. ↵

- L. Feinberg, “Transgender Liberation: A Movement Whose Time Has Come,” in Stryker, The Transgender Studies Reader, 4. ↵

- S. Whittle, foreword to Stryker, The Transgender Studies Reader, xi. ↵

- Feinberg, “Transgender Liberation.” ↵

- L. Feinberg, Stone Butch Blues (Los Angeles, CA: Alyson Books, 1993). ↵

- K. Bornstein, Gender Outlaw: On Men, Women and the Rest of Us (New York: Vintage, 1995). ↵

- Bornstein, Gender Outlaw, 4. ↵

- Bornstein, 12. ↵

- “About,” Human Rights Campaign, accessed May 12, 2021, https://www.hrc.org/about. ↵

- L. Duggan, “The New Homonormativity: The Sexual Politics of Neoliberalism,” in Materializing Democracy: Toward a Revitalized Cultural Politics, ed. Russ Castronovo and Dana Nelson (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2002), 175–193. ↵

- J. Puar, Terrorist Assemblages: Homonationalism in Queer Times (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007), xii. ↵

- J. Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (New York: New York University Press, 2009), 1. ↵

- Muñoz, Cruising Utopia. ↵

- C. Carruthers, Unapologetic: A Black, Queer, and Feminist Mandate for Radical Movements (Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 2018), 10. ↵

- Carruthers, 10. ↵

- Carruthers, 39. ↵

- J. Chambers-Letson, After the Party: A Manifesto for Queer of Color Life (New York: New York University Press, 2018), 4–5. ↵

- Chambers-Letson, 33. ↵

The view of sexuality that assumes individuals possess a fixed and innate sexual identity that is both universal and transhistorical.

The view that identity is a sociocultural construct that influences identity formation.

An institutionalized way of thinking and speaking, which creates a social boundary defining what can be said about a specific topic.

The scientific study of human sexuality, including human sexual interests, behaviors, and functions.

Emerging in the United States and the United Kingdom in the 1950s, the movement was a concerted effort to demand equal rights for homosexuals.

A term introduced by Eve Sedgwick to describe the view of homosexuality as relevant only to homosexuals. This view sees homosexuals as a specific group of people, a minority, within a largely heterosexual world.

A term introduced by Eve Sedgwick to describe viewing sexuality and sexual definition as important to everyone, rather than focusing on homosexuals as a distinct group.

A phrase coined by Gayle Rubin to describe the social apparatus that oppresses women.

Persons who do not have chromosomes, gonads, or genitals that meet medical expectations and definitions of sex within a binary system.

Refers to the performance of femininity or masculinity, and is most frequently used to describe the performance of gender expressions that differ from those associated with the performer’s natal sex assignment.

Most often someone who identifies as a man who behaves in an exaggerated performance of femininity. Drag queens are often associated with gay culture.

The capacity of language and expressive actions to produce a type of being.

Also known as Judith Halberstam, a gender and queer theorist and author, perhaps best known for work on tomboys and female masculinity.

An American professor, author, filmmaker, and theorist whose work focuses on gender and human sexuality, and a founder of Transgender Studies.

The largest U.S.-based LGBTQ+ advocacy group. It works for legal protections for LGBTQ+ persons, such as promoting legislation to prevent discrimination and hate crimes.

The U.S. military’s policy on gays, bisexuals, and lesbians serving in the military, introduced in 1994 by Bill Clinton’s administration. The policy required gay, lesbian, and bisexual persons to remain closeted while in the military. In exchange, it prohibited the discrimination of closeted service persons.

The marriage of two people of the same sex or gender in a civil or religious ceremony.

A strategy or one who enacts such strategy to gain access to, or assimilate into, existing social structures, like monogamous marriage or serving in the U.S. military.

Academics and activists use the term to discuss attempts by LGBTQ+ persons to assimilate into institutions like marriage and the military that reproduce hierarchy and are associated with oppression.

A political ideology that espouses economic liberalism, such as trade liberalization and financial deregulation, and small government. It accepts greater economic inequality and disfavors unionization.

An academic in the fields of performance studies, visual culture, queer theory, cultural studies, and critical theory. His book Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics (1999) uses performance studies to investigate the performance, activism, and survival of queer people of color.

Overlapping or intersecting social identities, such as race, class, and gender, that are produced by social structures of inequality.

A Black queer feminist activist and organizer. Her work aims to create young leaders in marginalized communities to fight for community interests and liberation.

Where identity should be abandoned to maintain the myth of universality.