3

Learning Objectives

- Discuss the features of folk and popular culture

- Explain the primary methods of diffusion

- Understand how to classify the world’s languages

- Identify the major world religions

- Describe ethnicity and how it relates to culture

Imagine that someone asked you to name a song that’s popular right now or maybe a character from a popular movie series or a logo from a common restaurant chain. Could you do it? What if you asked someone from a different area of the country to identify a popular regional dish, maybe scrapple if you live in Pennsylvania or gumbo if you’re in Louisiana or perhaps bisi bele bhath in the state of Karnataka, India? Could someone not from your region identify the dish? With globalization, we are often inundated with references to popular culture. But even as global popular culture has spread, regional cultural variations and folk culture remains. This chapter explores culture, including how is spreads and changes as well as two important features of culture, language and religion.

3.1 The Cultural Landscape

So what is culture, anyway? When we talk about culture, we mean the social behaviors and beliefs as well as material forms found in human societies. Very often, when students are asked to give examples of culture, they respond with things like clothing, food, and so on. Culture is so much more than just the material, although that’s often what we focus on. It’s easy to examine material culture – we can touch it, study it, see patterns at a glance. If I were teaching in a traditional classroom setting, for instance, I might notice that most of my students are wearing jeans, a clear indicator of popular culture. But culture goes far beyond the visual. What elements of non-visual culture can you think of? What about music? Or religious beliefs? Or laws? What about social norms that govern particular situations? These are all certainly elements of culture but they often go overlooked.

As explored in the introduction, culture includes both popular culture and folk culture. Popular culture refers to broad cultural features found dominant, heterogeneous societies while folk culture is practiced by smaller, homogeneous groups that are generally more rural and isolated. The scale of the territory covered by folk culture is generally much smaller, and because of that, it’s often more sensitive to the local environment. With popular culture, however, the environment might be modified in accordance with global rather than local values. Furthermore, popular culture is generally a product of more developed countries and often popular cultural is synonymous with Western popular culture.

So where do these cultural features come from? A social custom originates at a hearth, a center of innovation. With many folk cultures, the hearth is anonymous – originating from unknown sources at unknown dates, or even through multiple hearths. In contrast with folk culture, popular culture generally arises in more developed areas. Often, the intention of folk music is to tell a story, convey information about daily activities, or pass the time while working. Take one of the folk songs of Tripura, a state in northeast India, for example:

During heavy rain in June-July when

soil becomes blackish, all farmers are

starting to plough the land in paddy field.

This song is specific to a particular time, place, and agricultural practice. Even more modern folk music, such as the folk music of the Appalachian region, frequently features agricultural themes. Folk culture, because it arises in a particular, often isolated location, typically connects with a very specific cultural and geographic experience. Consider the lyrics of popular music, by contrast. Popular music, as clearly evidenced by the often vague and sometimes repetitive lyrics, is written by specific individuals, for the purpose of being sold to a large number of people and is often the product of more developed countries. Furthermore, popular culture is easily reproducible as a result of industrial technology and since it is generally a product of more developed, highly globalized countries, popular culture often spreads rapidly to other parts of the world in contrast with folk culture which tends to remain isolated or diffuses much more slowly.

When we examine our global cultural landscape, what cultural traits do we find? As discussed, we find music in both popular and folk forms. We also find differences in housing, with various styles of housing as well as building materials depending on the country, region, and time period constructed. Housing, like music, also takes folk and popular forms. As you travel around your city or town, look at the housing styles. Are some more traditional than others? Do some subdivisions have relatively standard and repetitive housing styles? These are commonly popular housing styles. Folk housing reflects locally-available building materials, cultural customs, and climate needs, perhaps featuring breezy courtyards in warm areas or pitched roofs where snow is more common. In New England, for example, the saltbox-style house was common in the colonial era (see Figure 3.1) and featured a steeply pitched roof with two stories in the front and one story in the rear.

Other folk housing styles in the United States include the I-House, found in the Middle Atlantic states, the Tidewater homes of the Atlantic coastal plain, and the shotgun houses of the south.

Today, housing styles are more reflective of the time period when they were built than local geography. For example, across the United States, ranch-style homes were popular from World War II until the mid-1970s and feature single stories and a long, low roof line (see Figure 3.2). Ranch homes can be found in a variety of locales, particularly in the southern United States. After the 1950s, many new homes in the United States can be described as having a neo-eclectic architectural style, borrowing elements of various historical styles such as Cape Cod, French Provincial, Tudor, or Colonial – and sometimes mixing several styles at the same time.

Clothing and food, like housing, can either reflect the local environment and cultural values, as with folk culture, or be more of a product of global trends, as in the case of popular culture. For example, do you generally cook meals based on what produce is locally and seasonally available? Or is your menu based on a variety of globalized meals that are popular – perhaps pizza one night, tacos the next, and then a stir fry? When you get dressed in the morning, do you put on clothes made from locally available textile materials, or were your clothes produced in a distant country and reflect popular style trends more than distinct cultural values? Sometimes there is a fusion of folk and popular culture. Perhaps you wear a hijab, a veil worn by some Muslim women, and also jeans. Maybe you enjoy some Salvadoran pupusas and curtido one day with relatives, and then the next day, have a fast food hamburger.

Even sports reflect a mix of both folk and popular culture. Take ice hockey, for example – where and why might that sport have originated? And yet today, we have a professional ice hockey team in Florida, the Tampa Bay Lightning. Lacrosse is actually the oldest organized sport in North America and originated as a tribal game played by indigenous Native American and First Nations groups. Football, referred to as soccer (which is short for “Association Football”) in the United States, is the most popular sport globally and likely arose in a number of different hearth areas as various kicking ball games were common in a wide array of cultures throughout human history. Modern popular football rules were devised in England as an attempt to standardize the various rules used by different English schools. American football more closely followed the rules of rugby, allowing players to handle and throw the ball, and similarly became standardized with intercollegiate competitions.

With so many different cultural features, and such an array of folk and popular cultural traits, how do we view our globalized cultural landscape? For some, a person’s values and beliefs are viewed as a product of a unique cultural tradition and should not be judged based on others’ views or practices. This idea is known as cultural relativism. Ethnocentrism, on the other hand, holds that one’s own culture can be used as a standard or a reference to understand or evaluate other cultural traditions. Just as we all likely have a mix of both folk and popular culture in our own lives, we likely at times can be both cultural relativists and ethnocentrists, sometimes understanding that cultural values are relative while at the same time, believing that certain values should be shared by all (though it might be helpful to remember that even these core values are a product of our own culture and upbringing.) What might be more helpful, perhaps, than labeling ourselves as one or the other would be to simply dig deeper – what values do you hold dear and why do you ascribe to these cultural ideals? How is your own cultural landscape unique and distinct, and what other cultural landscapes have you encountered? How might your life, and your beliefs about the world, be different if you’d been raised within a different cultural landscape?

3.2 Diffusion

A key principle for geographic study is the notion of spatial interaction, the flow of ideas, people, goods, or services from one place to another. This flow is dynamic, subject to change and evolve over time and is impacted by a variety of geographic factors to include physical and social features. So how does culture change and spread as a result of spatial interaction? Diffusion broadly refers to the spread of something to a wider area. There are two main types of diffusion: relocation and expansion. Relocation diffusion involves the physical movement of a person from one place to another, bringing their cultural ideas and traits with them. An immigrant from India moving to the United States and opening a restaurant serving dishes from her hometown would be an example of relocation diffusion. Relocation diffusion has occurred throughout human history as people move from one place to another. Folk culture primarily spreads through relocation diffusion.

Increasingly in today’s world, culture spreads through processes of expansion diffusion, no longer requiring people to physically relocate to spread cultural ideas. With expansion diffusion, features spread from one place to another in a way that grows increasingly large but still remaining in its original location. There are a variety of ways this expansive process might work, to include contagious diffusion, hierarchical diffusion, and stimulus diffusion – the three types of expansion diffusion. With contagious diffusion, the diffusion of an idea or product is widespread throughout a population and the spread can be likened to a contagious virus (hence the name.) “Viral” videos are great examples of contagious diffusion: one person posts it, then their friends like it and repost, and then others like and repost, and it quickly gathers millions of views. The original creator of the video never had to physically travel around and tell everyone about the video they’d made, it just spread from one person to another as people shared it.

With hierarchical diffusion, a cultural feature spreads from a person of authority or influence. A celebrity wearing a particular clothing brand might spur others to buy the same shirt. A highly followed social media celebrity might promote a certain product, inspiring others to go out and buy it. A ruler could decree that a particular religion is now the official faith in a country and numbers of adherents subsequently rise. All of these are examples of hierarchical diffusion.

Finally, stimulus diffusion is a bit different. With stimulus diffusion, it is the idea or principle that diffuses and stimulates new ideas rather than the original product. The original idea is changed or adapted by different cultural groups. There are many examples of stimulus diffusion throughout history. Pasta most likely originated in Asia, and yet when we think of Italian cuisine, we often think of quintessentially Italian pasta dishes rather than Italian versions of Chinese noodle dishes. Thus, the idea of noodles spread and was adapted by other cultures. Various products can be subject to stimulus diffusion, from personal computing technology to cream filled sandwich cookies. The original product might have inspired a later product which grew to be more even popular than the original.

As cultural features diffuse, the effects of and reactions to this diffusion vary depending on the local population. In some cultures, there is a blending of cultural features to form new traits known as syncretism. In other cases, a majority culture is fully dominant and members of minority cultures are expected to fully adopt the cultural features of the majority. This is known as assimilation. In still other cases, there is acculturation, where a majority cultural group exists and is dominant but minority groups still retain some level of their own cultural identity. Finally, there are societies that embrace multiculturalism, where individual cultural features are maintained and encouraged.

What barriers exist to cultural diffusion? Historically, physical barriers presented formidable obstacles. A wide river, expansive ocean, or tall mountain range would have prevented the spread of cultural features from one area to another. Today, most barriers are social. Perhaps a religious law prevents the spread of a popular movie to a certain area. Political barriers, language barriers, economic barriers, and so on all might hamper the spread of cultural features from one area to another. Conversely, these social features might spread a dominant cultural trait so well that local folk cultures are erased in the process, a phenomenon that has often occurred with the diffusion of language.

3.3 Language

There is a tremendous amount of diversity when we explore the world’s languages, and the differences we find aren’t just related to the sounds and structures of words. Our language is the lens through which we see and make sense of the world. Think about it for a moment – when we count in the English language using the Arabic numeral system (already a combination of languages and cultures), we use a base-10 system. So, when we count, we say things like twenty-eight, twenty-nine, and then we roll over to a new word once we reach another ten numbers – in this case, thirty. But not all languages use a base 10 system. Tzotzil, a Maya language, uses a base-20 system. Why? Well, we have 20 fingers and toes. The Tzotzil number for twenty-one is jun scha’vinik, meaning the first digit on the second man. One of my favorite numbering systems is in the Sora language, spoken by an indigenous group in eastern India. They use a base-12 number system and a base-20 system, so the number 34 would be conceived of as twenty-twelve-two. And those are just differences in numbering! Think about how differently you’d look at the world if you had a distinct word for light blue (mizu in Japanese), no notion of time as a distinct, abstract idea (for example, the Amondawa language), or maybe no words for discrete numbers at all (as in Pirahã language.) Sometimes we think that our framework for seeing the world is universal, when in fact, it varies significantly from culture to culture and is expressed in the way we communicate to one another.

Languages are simply structured systems of communication where collections of sounds and/or letters have shared meaning. Note that a literary tradition is not a requirement for a language. Hundreds of languages are only transmitted orally, though a lack of a written language system makes these languages particularly challenging to study and document. There are around 6,500 different languages spoken in the world today. While they might all seem quite different, we can actually group them based on shared patterns of sounds and common grammatical structures, all pointing toward a shared, historical origin. Consider your own family tree: there is your family and perhaps your siblings, cousins or parents and they are connected to your grandparents who are connected to your great-grandparents and so on, all the way back to the first humans who ever lived. We are all connected, some more recently on humanity’s family tree and some more distantly. Similarly, we can create a family tree of languages, connecting languages that are more closely related to languages that existed in the distant past.

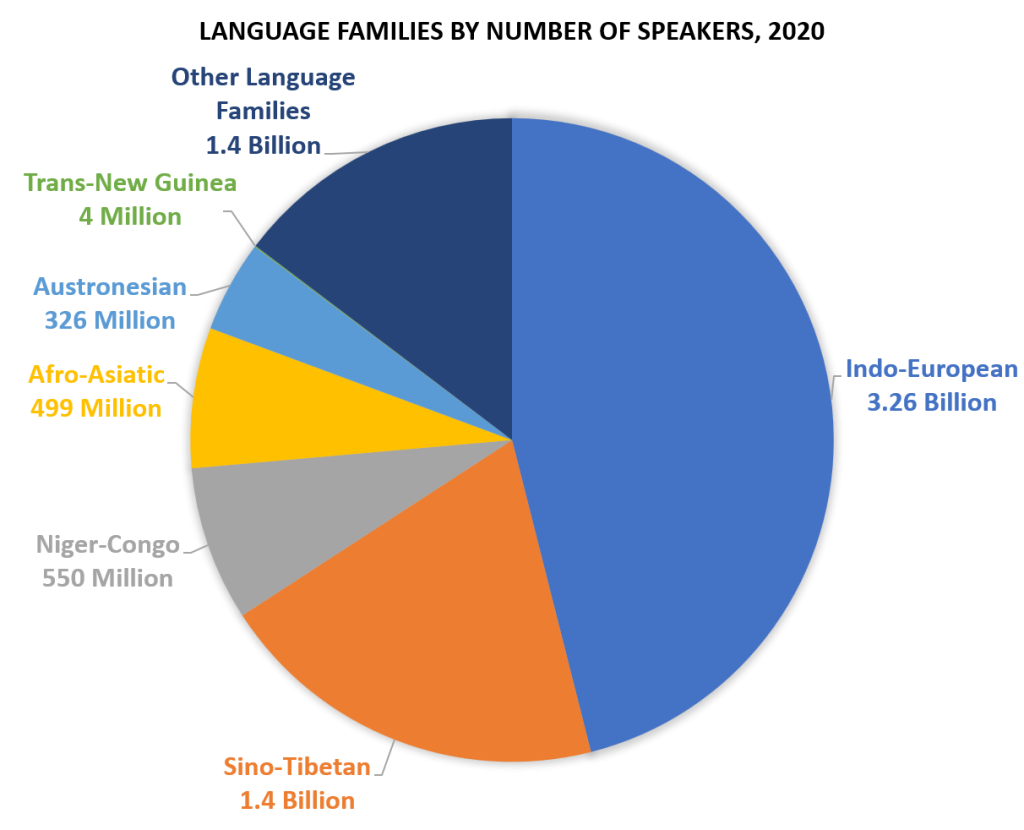

Let’s begin at the trunk of our language family tree. Language families include large groups of languages that were united by a common ancestral language before recorded history. There are numerous language families but the six with the most number of native speakers include: Indo-European (which includes English, the Romance languages, and Hindi, and comprises around 42% of the world’s population), Sino-Tibetan (which includes Mandarin), Niger-Congo (which includes Swahili and is Africa’s largest language family), Afro-Asiatic (which includes Arabic), Austronesian (which includes Javanese), and Trans-New Guinea (which includes over 400 distinct Papuan languages) (see Figure 3.3).

As we continue up our tree, we reach the language branches. A language branch is a collection of languages within a language family that are related through a common ancestral language that existed several thousands of years ago. For example, the Semitic language branch is a group of related languages within the Afro-Asiatic language family. Finally, a language group is a collection of languages that share a common origin in the relatively recent past. Within Indo-European language family, there is the Germanic language branch and then the West Germanic language group which includes the languages of English and German. There are numerous similarities between languages in a language group.

Even within languages, we can find differences. A dialect refers to a particular regional speech pattern found within a language. Generally, dialects are mutually intelligible, but there might be differences in spelling, vocabulary, grammar, and/or punctuation. The English language has numerous different dialects from Received Pronunciation, associated with higher class British boarding schools, to Scottish English to American English to Australian English. Within dialects, we often find numerous different accents. Accents and dialects are similar, and often it is difficult to determine if a variation of a language is a distinct dialect or is an accent. In general, accents refer to differences in how people pronounce words while dialects refer to broader differences not only in pronunciation but also in vocabulary and grammar. Furthermore, as we zoom in to a particular region, sometimes we find dialects or accents within dialects, like a language fractal. Within American English, for example, we find a Southern dialect (sometimes colloquially referred to as a “southern accent”) and if we zoom in even more, we find regional dialects or accents specific to certain places, such as Appalachian English. What languages do you speak? What is your dialect and accent?

Languages are always changing and evolving, as evident from comparing historical literature to modern writing. Sometimes languages begin to have fewer speakers and eventually become endangered or even extinct. Generally, languages disappear as a result of colonization, conquest, or the presence of a more dominant language in the region. Within the United States, for example, many American Indian children were sent to boarding schools during the late nineteenth through mid-twentieth centuries where they were forced to speak English, adopt American cultural customs, and were punished for speaking their native language. Sometimes, indigenous languages aren’t actively discriminated against, but the presence of a more dominant language of trade and the lack of local languages used in schools leads to a decreasing number of speakers with each generation. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) maintains an online atlas of the world’s endangered languages and, as of 2020, it lists 1,114 languages as either “severely” or “critically” endangered. Some of these languages only have a few speakers remaining. The Ainu language of Japan, for example, only has two remaining native speakers. Wukchumni, a language spoken by a Native American tribe, has just one remaining fluent speaker. When these languages die out, a unique piece of how humans see and understand the world dies with them. Furthermore, because language and culture are so closely intertwined, it represents a loss of a key marker of cultural identity.

Sometimes, languages can be revived, either reversing trends in the decline of a language or resurrecting a language that was previously extinct. Some researchers and advocates, for example, have worked closely with indigenous groups to ensure their language is documented, preserved, and encouraged. Perhaps the most successful example of a revived language is Modern Hebrew, which was effectively extinct and used only in religious ceremonies until the late nineteenth century. Today, around 7 million people speak Hebrew fluently. Reviving endangered languages is not without challenges, however, as an example in Wales demonstrates. In an effort to preserve the Welsh language, which has been quite successful, road signs in Wales are required to be bilingual. So, when a road sign went up in Swansea, officials sent an email asking for a translation and received what they assumed was the Welsh translation in reply and printed it on the sign. Unfortunately, the Welsh text of the sign read: “I am not in the office at the moment. Send any work to be translated.”

3.4 Religion

As with languages, there is a wide array of religious belief and expression in our world today. Geographers distinguish between two types of religions: ethnic religions, which are belief systems primarily associated with a particular ethnic group and generally tied to a particular geographic area, and universalizing religions, which attempt to appeal to all people and operate on a global scale. Because of their global reach, universalizing religions typically seek to convert new believers, while this is less common among ethnic religions. The three largest universalizing religions (see Figure 3.4) are Christianity, Islam, and Buddhism. Ethnic religions include Hinduism, Judaism, and Shinto. That said, sometimes there is more overlap between these distinctions than you might initially expect. Many Christian churches around the world, for example, have highly ethnic components, such as the Greek Orthodox Church. Similarly, some ethnic religions accept conversion and do not limit membership to a particular ethnic group, such as in some branches of Judaism.

Defining religion presents its own challenge. How would you define “religion”? If it’s limited to a belief in a particular deity, then many large and well-known religions would be excluded, such as many expressions of Buddhism. If it’s a particular set of beliefs and practices, that definition might exclude religions like Hinduism which are more focused on individual religious expression and that have little or no over-arching dogma to which all believers ascribe. In truth, there is not one, all-encompassing definition of religion. A religion could perhaps be described as a system of beliefs, practices, worldviews, and/or ethics. Furthermore, an increasing number of people in the world are not religious, either atheist, meaning they do not believe in a God or gods, agnostic, meaning they believe you cannot know whether or not God exists, or simply nontheistic, believing it is unnecessary to have religious belief. And these categories themselves are not exclusive. One could be agnostic but find value in religious rituals. Or personally atheist but believe religious expression can be beneficial for people – or not. As we explore the world’s religions, keep in mind that just as your religious belief or non-belief likely differs from the exact beliefs of your neighbor, so too is there a wide array of individual beliefs and practices even among the major world’s belief systems.

Within the world’s religions, there are various divisions, known as branches, denominations, and sects. A branch is a large division within a religion. The three largest universalizing religions have different branches and these branches have distinctive geographic distributions. A denomination is a subgroup of a religion within a branch that has a common tradition and typically has a single administrative body. Finally, a sect is a further division within a religion that characterizes a smaller group that has split from an established denomination.

Hinduism is one of the oldest of the major world religions, dating back at least 4,000 years. There are over 1 billion followers today, mostly in India and in places where there are large Indian populations. If we look at the actual beliefs of Hinduism more closely, we see that the theology is very broad, without the rigid doctrines we might find in other religions. For Hindus, it is up to the individual to decide the best way to worship God. Hinduism is polytheistic, meaning they believe in the existence of many gods. The three main deities are Brahma (the creator), Vishnu (the preserver of good and order), and Shiva (god of destruction and creation). Because Hinduism does not have a common creed, specific religious authority, or strict moral code, it is challenging to define and generalize Hindu belief and practice. In general, however, Hindu expression typically includes the belief in four key elements: karma, the notion that your deeds, good or bad, will return to you; reincarnation, the belief that you are the sum of numerous past existences; dharma, the laws and duties of being, which include restrains and observances; and worship, or your communion with the gods. Each Hindu is free to worship in their own way, perhaps experiencing the divine through yoga or through the study of Hindu sacred texts such as the Vedas. Figure 3.5 displays the Sri Ranganathaswamy Temple in Tamil Nadu, India, one of the largest religious complexes in the world that attracts over 1 million visitors during its annual 21-day festival.

Buddhism is the world’s fourth-largest religion with over 520 million adherents and stemmed from Hinduism. Its founder, Siddhartha Gautama, was a Hindu who lived around 500-400 BCE and was born into an aristocratic family. While in his early years, he enjoyed a life of privilege, Siddhartha grew disenchanted with his life and the suffering he saw around him. He was ultimately searching for a way to end the cycle of death and rebirth, known as samsara. But how do you end this cycle? Siddhartha determined that there were four noble truths of our human existence: 1. Life is suffering. 2. The cause of suffering is desire. 3. There is a way to end suffering. 4. The way to end suffering is the eightfold path. These truths might seem pessimistic, but in many ways, they are realistic. Suffering is, indeed, universal, but for Siddhartha, suffering was a function of our denial of our true existence or our desire. Think about when you have suffered – were you upset over a lost love, sad that your pet died, or distressed over an injury or illness? For each of these cases, Siddhartha taught that by connecting our happiness with individuals, things, or our physical bodies, we ultimately suffer because these things are impermanent.

So how do you relieve suffering? By following the eightfold path, which includes: right view, right resolve, right speech, right conduct, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration. This path is intentionally vague, because in Buddhism, as in Hinduism, there is a multitude of possible paths. By following the eightfold path, one eventually enters nirvana, a state of absolute desirelessness and peacefulness, and is liberated from the cycle of samsara. Siddhartha is often called “the Buddha,” but this title really means one who has achieved enlightenment or “one who is awake” and could be applied to other enlightened beings as well.

Now let’s turn to the Abrahamic faiths, so-called because they trace their origins to the patriarch Abraham. These religions include Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, as well as Baháʼí. According to religious texts, Abraham had two sons: one, Ishmael with his wife’s servant Hagar; another, Isaac with his wife, Sarah. Muslims trace their ancestry through Ishmael, while Jews trace their lineage through Isaac.

Judaism is an ancient religion, remarkable in the fact that while many other quite similar religions existed at the time have since vanished, Judaism still exists today, despite continued persecution throughout history. Jewish religious practice in ancient times was centered around a temple in Jerusalem within the modern state of Israel. This temple was destroyed by the Babylonians in 586 BC, but was eventually rebuilt by King Herod. It, too, was destroyed in 70 C.E. by the Romans and was never reconstructed. Following the destruction of the second temple, much of the Jewish population was forced out of their homeland, creating what’s known as a diaspora – a group of people who are living outside of their geographic homeland.

Judaism is a monotheistic religion, professing a belief in one God. Before Roman conquest, Jewish ritual practice was centered around temple worship. God was believed to have physically dwelled within the temple and thus the temple was the site of ritual sacrifices and the high priests who presided over them. Once the temple was destroyed, though, where was God? Judaism underwent an evolution and a shift in theology from the notion that God physically dwells in the temple to the idea that God is wherever Jews are. Thus, there was the creation of the synagogue (see Figure 3.6) and an emphasis on home rituals and observances. Priests no longer became important, but rather, rabbis who could interpret Jewish laws and commandments found in the Hebrew Bible. (Note that the Hebrew Bible is referred to as the “Old” Testament in Christianity – but it’s only “old” if you think there’s something new.) Today, Judaism has several branches including Orthodox, Conservative, Reform, and Reconstructionist.

Christianity historically began as a reformation of Judaism. Jesus, who was Jewish, is considered to be the “messiah” or “anointed one” by his followers. He was born in 4 BCE and was killed by the Romans most likely in either 30 or 33 CE, only a few decades before they destroyed the Second Temple in Jerusalem. The Romans were worried that he would incite a revolt and crucified him, a manner of death that was generally reserved for political prisoners. His death is discussed in the Biblical gospels as well as in other historical sources.

Today, there are over 2 billion Christians worldwide and Christian belief is quite varied, particularly with regards to Biblical interpretation. Some take a more literal interpretation of the Bible as the authoritative word of God, while others look at the Bible as more metaphorical, part of an evolving conversation with the divine. Christianity has three major branches: Roman Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy, and Protestantism. Roman Catholicism is the oldest branch of Christianity. Catholics believe that God conveys his grace to humanity through the seven sacraments: Baptism, Confirmation, Penance, Anointing of the Sick, Matrimony, Holy Orders, and most importantly, the Eucharist. Eastern Orthodoxy developed as a result of a split in 1054 CE known as The Great Schism. Russian Orthodox makes up 40% of this branch. The Protestant reformation began with Martin Luther on Oct. 31, 1517. Luther believed that individuals should be able to directly communicate with God, without the need for a priest as an intercessor, and that grace was given through faith.

Islam is yet another of the Abrahamic faiths and is the second-largest religion in the world, behind Christianity, but is the fastest growing, primarily because it is found in places with high natural increase rates. Islam is a monotheistic religion whose adherents believe in one God, Allah, and believe that Muhammad is a prophet of God. Note that “Allah,” the term for God used in Islam, simply means “the God” in Arabic, just as “Elohim” similarly does in Hebrew. While outsiders sometimes seem to view Allah as “some other God,” certainly Muslims believe that Allah is the same God as the deity found in the Jewish and Christian traditions.

The word Islam comes from the root word SLM meaning “submission,” and this core principle is essential to understanding Islam. Muslims believe that submission to Allah is key and every Muslim belief centers around this principle. Muhammad, who lived from 570 to 632 CE, was an orphan raised by relatives who would often spend time meditating and praying in the caves near his hometown of Mecca, in what is now the state of Saudi Arabia. During one of these prayer sessions, he is believed by Muslims to have received the first in a series of revelations. These revelations, believed to be recitations directly from Allah, are compiled in the Qur’an. Muhammad is thus seen as a prophet in Islam, alongside other prophets including Abraham (Ibrahim in Arabic), Noah (Nuh), Moses (Musa), and Jesus (Isa).

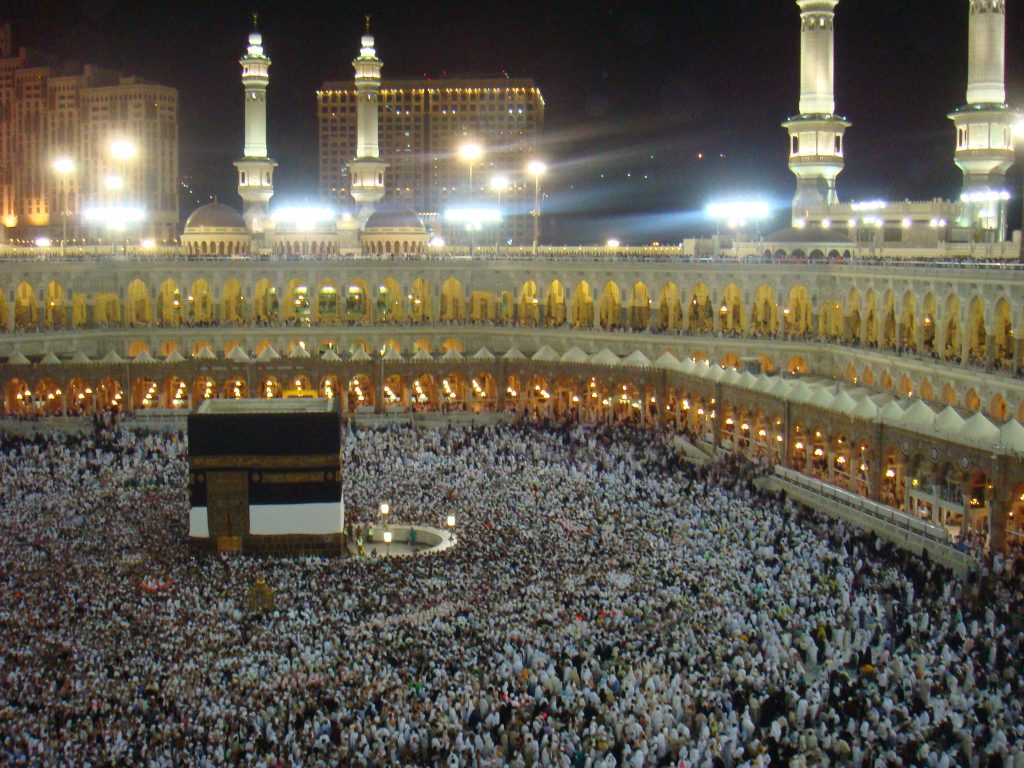

There are five core practices in Islam, known as the five pillars. These are: shahada, the statement of faith – “There is no god but Allah and Muhammad is the messenger of Allah;” salat, prayer five times a day; zakat, the giving of alms – 2.5% of all assets, not just income; sawm, a month of daytime fasting during the month of Ramadan – no food, drink, or sex during daylight; and hajj, one pilgrimage to Mecca (see Figure 3.7) for those who are able. Some students often mistakenly think that jihad is one of the five pillars, but it is not. Furthermore, jihad actually means a “holy struggle” and is generally seen as a metaphorical struggle with one’s faith and doubts, rather than a physical struggle against other individuals.

Today, there are over 1.9 billion followers of Islam. Though there are majority Muslim countries across parts of North Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Southwest Asia, most Muslims actually live in South Asia, with Indonesia having the largest Muslim population in the world. Islam can be broadly divided into two main branches: Sunni (around 85% of adherents) and Sh’ia (around 15%) (see Figure 3.8). These groups split over who should be caliph, the leader of Islam, after the death of Muhammad, which was challenging as Muhammad had no male heir. The Shi’a believed that the successor should be a direct descendant of Muhammad, who they viewed as his son-in-law Ali (so Shīʻatu ʻAlī means “followers of Ali”), while the Sunni believed that the leader did not have to be hereditary, and were more interested in the leader’s ability and charisma. Like Judaism and Christianity, individual belief and practices vary among Muslims. Some Muslim women believe in the wearing of head coverings, known as hijab, and modest dress, while others do not. Also as with other religions, there are also more fundamentalist groups within Islam who hold a strict, literal interpretation of religious scripture.

There are numerous other world religions as well. The Baháʼí Faith is essentially a synthesis of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam and believes in the unity of all people and the value in all religious expressions. Sikhism is a fusion of Hinduism and Islam based on the teachings of Guru Nanak, who lived from 1469-1539 CE. Within Japan, we find the ancient religion of Shinto, a polytheistic religion whose followers believe that a divine power inhabits all things, known as animism. Most people in Japan actually practice a combination of both Shinto and Buddhist beliefs. Animistic beliefs are also common across traditional African religions which are practiced by around 100 million people.

In addition, an increasing number of people in the world are considered to be among the so-called “religious nones,” those who are unaffiliated with any belief system. Within the United States, around 12% of U.S. adults identified as “nothing in particular” in 2009 on a Pew Research survey. By 2018-2019, that figure had risen to 17%. Across Europe, while most people identify themselves as Christian, relatively few regularly attend church and here too there has been a rise of adults describing themselves as religiously unaffiliated.

3.5 Religious Diffusion and Conflict

Religious beliefs spread around the world through various processes of diffusion. Missionaries help transmit religious ideas through relocation diffusion. For Christianity, the spread of the Roman Empire accompanied a mix of contagious diffusion, through daily contact among believers in towns and nonbelievers in the countryside, and hierarchical diffusion, occurring as a result of Roman leaders embracing Christianity and proclaiming it the official religion. For Buddhism, the emperor Asoka was predominantly responsible for its diffusion. He was the emperor of the Magadhan Empire around 250 CE. His son led a mission to modern-day Sri Lanka and converted all the subjects to Buddhism. As the merchant routes spread, so too did the Buddhist faith. Islam spread with the conquest of the Islamic Empire and continues to grow today as a result of voluntary conversion, migration, and proselytization.

As human geographers, we can explore the paths of religions as they grew and spread, but we can also examine the geography of religion on a more local scale by exploring sacred sites. Religious structures play a critical role in bringing people together and both reflect and reinforce underlying religious beliefs. These places often relate to a founder’s life or to historical events in the religion’s history. Each of the world’s religions has sites that they consider to be holy, and in some areas, these holy sites are located in close proximity to the holy sites of other faiths.

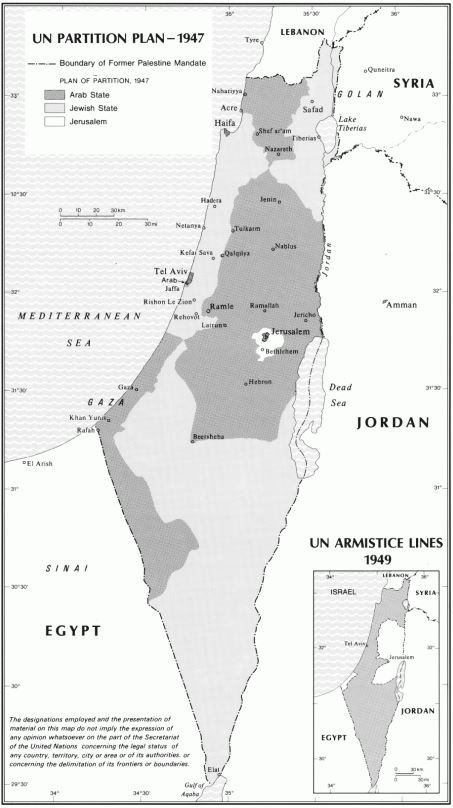

At times, this has led to conflict. In Jerusalem, for example, the holiest site for the Jewish people, the remnants of the destroyed Second Temple, is located right next to one of the holiest sites for Muslims, the Dome of the Rock where Muhammad is believed to have ascended into heaven (see Figure 3.9). Christians, too, often make pilgrimages to Jerusalem to visit the historical sites where Jesus walked and preached. This region has been the site of broader territorial conflicts for centuries. Following World War I, Britain had secured a mandate to administer the then-territory of Palestine. The Balfour declaration in 1917 by Great Britain stated that Britain supported the concept of a Jewish homeland and led to a mass of Jewish immigration to Palestine, and subsequently to rising conflicts between Jews and Arabs in the region. There had been continued calls for a Jewish homeland at least since the late 1800s, but these calls took renewed urgency following World War II and the murder of approximately six million Jews. In some countries, huge percentages of the Jewish population were killed, including 90% of the entire Jewish population of Poland and over three-quarters of the Jewish population of Slovakia. The United Nations ultimately settled on a plan to partition the territory of Palestine into an Arab state, a Jewish state, and U.N.-administered city of Jerusalem (see Figure 3.10). The surrounding Arab states immediately opposed this plan and armed clashes broke out. Ultimately, Israel declared independence in 1948 and subsequently gained additional territory, including the areas that were intended to be part of the Arab state, after a number of wars with surrounding countries.

It might be useful to pause a moment and consider why the Jewish people would demand a homeland. If you are the minority everywhere, then there’s really nowhere you’d be completely safe from persecution. If you’re the minority everywhere, then the Holocaust could happen again. Furthermore, Jewish text states that this land was given to them by God, so Jews view this land as their divine right. On the other hand, can you see why Palestinians, and the surrounding Arab states would not support the partition? While you might support a Jewish homeland intellectually, it’s hard to give up your land. And Palestinian Arabs have lived here for centuries. So, on the one hand, you have a group claiming the region because it’s their historical homeland for hundreds of years and on the other, a group claiming it because it was their homeland years earlier and because they believe their religious texts decrees that it is their land. Furthermore, recall that both Judaism and Islam are both Abrahamic faiths and are quite similar, especially when you compare them to other religious traditions. Additionally, as is often the case with territorial conflict, this conflict stems from a combination of ethnic and religious factors.

In the current situation, there is the independent state of Israel and within that state, Palestinian-inhabited areas, though there is no official state or territory of Palestine (see Figure 3.11). Within the United Nations, Palestine is included as a “non-member observer state,” though many have fought for Palestinian statehood. Complicating the situation further is that there are two Palestinian areas, one in the Gaza strip and the other in the West Bank. In the West Bank, we also find Israeli settlements. Both Palestinian areas are walled off from the rest of Israel and Palestinians who wish to cross must go through lengthy checkpoints, if they are allowed to cross at all. The Israeli government maintains that these walls and precautions are for the safety of Israeli citizens. Over half of the population of Gaza lives below the poverty line and residents of Gaza maintain that the Israeli blockade of the area has prevented needed goods and services from entering the area. In addition, the presence of Israeli settlements further complicate the peace process because it would be challenging to return to the U.N. partition plan with substantial numbers of Israelis living in what was intended to be an Arab state. Some, including the United Nations and the European Union, view these settlements as a violation of international law. The Israeli government, however, views these settlements as legal since they maintain to have legal claim to the entire territory.

Globally, we see religious tensions existing in many different places. A challenge we’ll likely face is the rise of secularism (non-religion) alongside areas where conservative religion is flourishing. Rising secularism in North America and in most of Europe has sometimes been at-odds with the the deep religious views expressed by many in the developing world, the same areas that were once colonized and controlled by the West. There has also been a resurgence of religious fundamentalism, which some groups see as a way of keeping their particular culture distinct from an increasingly “Western,” secular society. The Taliban, for example, has imposed very strict laws which scholars note are not in line with the Qur’an but Taliban adherents see as a method of maintaining their interpretation of Islam free from global influence.

3.6 Ethnic Identity

Ethnicity refers to a shared identity with a group of people who have a common history or cultural tradition, and ethnic identity can be a source of pride for many, a link to the experience of ancestors and to cultural traditions, such as food and music preferences. Ethnicity can be closely tied to folk culture, language, and religion. It is a natural human tendency to seek a shared sense of belonging, but there is also the unfortunate tendency to “other,” to label a particular group of people as something wholly “different” from ourselves. It is this “othering” that leads to prejudices. For some, ethnic identity can be primarily a function of our distant ancestry. In the United States, for example, someone might identify as being “Italian,” though this identification might only relate to the food they cook (or enjoy eating) and to where their relatives emigrated from. For others, ethnic identity can represent the core of who you are.

Ethnicity is distinct from race, which refers to the identity with a group of people who have a shared biological heritage. Is race socially constructed, or is there a biological basis for it – or is it a combination of both? Modern scholars view the distinct, racial categories often used today as socially constructed, meaning they have been created by society. This is apparent from the labels we often use to define various races, such as “white” and “black” and how we make these distinctions. No one’s skin tone is really white or black. Yours might be a rich chocolate color or a warm olive tone or ivory with a hint of pink. That said, there are inherited features such as skin color and hair texture that can dramatically impact how a person is perceived by the wider society. Racism refers to the belief that race corresponds with differences in both physical appearance and behavioral traits and the belief that one race is superior over another. This is not to say that the mere idea of race produces racism, but it is often the labeling of others and the practice of “othering” that is the first step in developing prejudices and racist views.

There can be some overlap between race and ethnicity with regard to culture. Someone might identify as “Black” with regards to race and also the African American ethnicity, connecting to their African heritage. Someone else, however, might identify as “Black” but their ancestors more recently came from the Caribbean and so they may not identify with an African ancestry. Furthermore, some people may identify as multiple races or ethnicities.

Ethnicity is also different from nationality, which refers to your attachment to a particular country, and is explored further in the Political Geography chapter. However, ethnicity and nationality can sometimes go hand in hand. When new countries are created, they are often separated on the basis of ethnicity – but you can rarely separate two ethnicities completely. When creating national boundaries, how do you decide which ethnicities (and their territories) to include in a new country, and how do you decide which to separate? If multiple ethnicities exist within a country, how do you decide which ethnic group should rule? What happens if you’re a majority ethnic group that wants to rule, and the minority is resistant? In some cases, the majority ethnic group or the ruling ethnic group turns to ethnic cleansing, which is a process in which a more powerful ethnic group forcibly removes or kills a less powerful one in order to create an ethnically homogeneous region. Genocide, specifically referring to the intent to destroy a particular ethnic group, is a crime under international law. There have been numerous instances of ethnic cleansing throughout history including ethnic cleansing campaigns by the Nazi government, the Cambodian genocide in the 1970s, and the Rwandan genocide in the 1990s. More recently, the Myanmar government has been accused of ethnic cleansing related to their Rohingya population, an ethnic minority within Myanmar who are viewed by the government as illegal migrants and deny them citizenship. Around half of the 1 million Rohingya have fled to neighboring Bangladesh.

Our cultural practices and beliefs are highly personal – and yet they connect us to broader ethnic, religious, and linguistic communities. Furthermore, our cultural beliefs can significantly shape how we view and interact with others outside of our community. For some, this might mean embracing multiculturalism and enjoying sharing and learning from the cultures of others. For others, particularly those who are involved in territorial disputes or who have a historical grievances against another ethnic group, these cultural differences can have severe consequences. Ultimately, our culture helps shape who we are and transmits our values and ideals to the next generation.

the social behaviors and beliefs as well as material forms found in human societies

broad cultural features found dominant, heterogeneous societies

cultural features practiced by small, homogeneous groups that generally live in rural, more isolated areas

the idea that a person's values and beliefs are a product of a unique cultural tradition and should not be judged based on others' views or practices

evaluating or judging another culture's traits based on one's own cultural system

diffusion of culture through the physical movement of people from one place to another

the spread of culture through an expansive process, growing larger as it spreads but remaining in its original location

the rapid and expanding spread of a cultural feature from person to person

the expansive spread of a cultural feature from a person of influence or authority to the wider population

the spread of an idea or principle rather than the original cultural feature or product

the blending of cultural features to form new traits

the process by which a minority group adopts the values and traits of a more dominant cultural group

when a dominant culture is present and exerts influence but minority cultural features are still retained

the presence of multiple, distinct cultural identities

a structured system for communication

a large group of languages that were united by a common ancestral language before recorded history

a collection of languages within a language family that are related through a common ancestral language that existed several thousands of years ago

a collection of languages that share a common origin in the relatively recent past

a particular regional speech pattern found within a language

a difference in the pronunciation of words within a language

a belief system primarily associated with a particular ethnic group and generally tied to a particular geographic area

a lack of belief in God/gods

the belief that the existence of God/gods cannot be proven

not having a belief in God/gods

a large division within a religion

a subgroup of a religion within a branch that has a common tradition and typically has a single administrative body

a division within a religion that characterizes a smaller group that has split from an established denomination

the belief in many gods

a group of people who are living outside of their geographic homeland

the belief in one God

a form of a religion that is characterized by a strict, literal interpretation of scripture and a return to the religion's core principles

the belief that objects, people, and creatures all possess a divine essence

a member of a religious group who helps diffuse and promote their religion in an area

a shared identity with a group of people who have a common history or cultural tradition

identity with a group of people who have a shared biological heritage

the belief that race corresponds with differences in both physical appearance and behavioral traits and the belief that one race is superior over another

a personal allegiance to a particular country

the forced removal or killing of an ethnic group in order to create a more ethnically homogenous region