7

Learning Objectives

- Describe the key innovations of the Industrial Revolution

- Understand how the features of industry impacts industrial location

- Explain how to measure development

- Discuss the features of the modern global economy

- Identify the characteristics of sustainable development

Consider the things you use on a daily basis. Where were they made? If you used a bowl or plate today, did you make it yourself or buy it in a store? Did you weave and sew your own clothing, or purchase it? Where was it made? Most products have a country of origin label on it, and students are often surprised at the great distances the products they use have traveled. You might have a pen from Mexico, a phone from India, a shirt from Cambodia, and a car from Japan. Our world has become increasingly globalized, and this doesn’t just affect where we buy goods from, but where jobs are located, what types of development arise in different places, and how countries interact with one another. The Industrial Revolution profoundly changed our human landscape and for many of us, the jobs we currently hold or are working toward only exist as a result of industrial development. This chapter will explore these changes, beginning with the historic causes and changes that resulted from the Industrial Revolution, the patterns of industry found in the world today, and our global economic landscape.

7.1 The Industrial Revolution

How would your ancestors have made the items they needed for daily life? They might have whittled a spoon, forged a knife, or knitted a sock. If they had extra materials, they may have bartered with a neighbor, perhaps trading a handmade scarf for a chair. These types of home-based manufacturing activities were known as cottage industries. Even today, cottage industries remain and you can often buy handmade items produced in the home from online marketplaces. For a very long time, this was how all of our goods were produced.

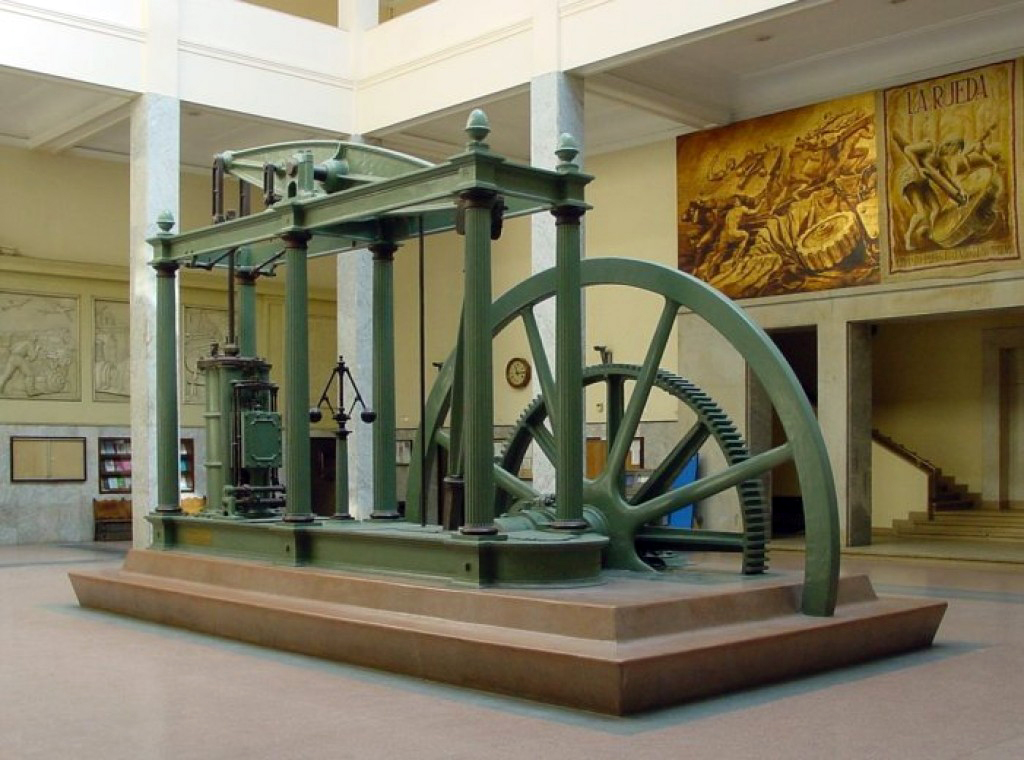

The Industrial Revolution, however, marked a dramatic shift in how we would buy and sell goods. The Industrial Revolution refers to a transition to new manufacturing processes beginning in the United Kingdom from the mid-1700s to the mid-1800s and gradually diffused to the rest of the world. There were a number of technological breakthroughs that occurred to spur a transition from cottage industries to wider-scale, industrial production. Most notably, perhaps, was the invention of the steam engine (see Figure 7.1), which not only led to the creation of machines that could be used to replace human labor, but also the transportation of industrially-produced items over vast distances. The creation of the steam engine enabled more, and better, iron production, since steam engines could drive huge blast furnaces and supply them with a steady stream of heat that was necessary for iron production.

With this shift to steam engines came a shift in the sources of fuel. Previously, machines often relied on moving water, so a mill would need to be located along a river, for example, harnessing the power of the moving water. Other forms of production that required heat, such as smelting, generally used wood, which had become quite scarce across Europe. The Industrial Revolution led to the transition from wood and other bio-fuels to coal, which was far more abundant.

The transition to steam power also led to the invention of a variety of new machines which were able to replace human-powered devices. Imagine, for example, that you wanted to build a table. How would you shape the legs? You could carve and whittle them down, but this would be very time consuming, or use a device that relied on human power to turn and shape wood (which often required two people, one to spin the wood and the other to shape it.) With the invention of the mechanical lathe, all sorts of products could be shaped and turned on an industrial scale – and interestingly the mechanical lathe led to the invention of other machine tools, since the lathe itself could help create new machine parts that would have not been able to be produced with human power previously. Other tools like boring machines and planers similarly led to innovations in other products.

Steam engines could also power numerous sewing machines and weavers within one building leading to a complete reshaping of textile manufacturing, which had previously been a cottage industry. Other textile innovations allowed materials to be woven faster, and in larger widths, than ever before, and for yarn to be spun at higher speeds. Before the Industrial Revolution, much of the world’s textiles came from India. With the new technology in Britain, however, and British colonial expansion, the power shifted and Britain established cotton plantations in places like the Americas to support its textile operations. In this way, the shift from cottage industries to industrialization, and a focus on mass-producing goods, led to an unprecedented need for resources that often became the focus of colonization.

Finally, industrial innovations were applied to food processing as well. Whereas preserving foods on a small scale was a home-based endeavor previously, in 1810, a Frenchman started canning food in glass jars, which later switched to tin cans, as a way to feed large numbers of people while avoiding spoilage. Canned food spread across Europe, with the British Army and Royal Navy purchasing considerable quantities of canned foods, such as canned beef and soups. The idea that foods could be preserved so long after harvest further fueled industrialization itself, since more and more workers were moving to the cities where they no longer grew their own crops and access to fresh foods might be limited. This more steady supply of food supported a substantial increase in population. In England alone, the population increased from 8.3 million at the turn of the 19th century to 16.8 million by 1850.

Ultimately, though the Industrial Revolution would spread across Europe to the United States and beyond, the fact that so many industrial advances first began in Britain gave it a considerable advantage. The invention of the steam engine, for example, led to the creation of the steam-powered ship, which gave Britain considerable military advantage in defending itself against adversaries and acquiring new territory, and Britain would remain the world’s largest manufacturer until the early 20th century, when it was surpassed by Germany and then the United States.

So if the Industrial Revolution happened over 200 years ago, how is it still relevant to modern geography? First of all, when we look at the modern map of Europe, and really more broadly at the map of global development, we see that the industrial powers in the world today still often correspond with the areas that were first to industrialize. The Rhine-Ruhr Valley, for example, located in Northern Germany and stretching into Belgium, France, and the Netherlands, was located in close proximity to coal fields and was a site of significant iron production. Today, this region includes the largest metropolitan region in Germany and has a specialization in finance and high tech industries. Even where areas have shifted, like cities within the Rhine-Ruhr valley, from heavy manufacturing to more high tech industries, they have largely retained their economic dominance.

The Industrial Revolution’s effect on the environment was also significant and continues to be a concern. The rise of factory production led to a considerable increase in air pollution. Water pollution, too, intensified, as factories often discharged pollutants directly into rivers and streams. Even today, the way we often produce goods and travel is largely connected to the burning of fossil fuels – the same resources that fueled our early industrial development.

The Industrial Revolution also brought about an increase in specialization. Consider, for instance, your ideal career. Perhaps it’s teaching third grade. Perhaps it’s working as a geospatial analyst on national defense projects. Perhaps it’s working to alleviate child hunger as part of a nonprofit. Think for a moment about how highly specialized these careers are. Not that long ago in our history, we were basically all farmers. Now we have a tremendous variety of jobs we might hold, and most of these jobs are very narrowly specialized. Particular geographic areas tended to specialize as a result of Industrial Revolution as well, perhaps computer technologies or automobile manufacturing. This specialization gave areas a competitive economic advantage.

Economic prosperity was not universal, however, and some critics view the Industrial Revolution as bringing about broader social changes that were not altogether positive. The rapid rural-to-urban migration spurred by industrialization led to overcrowded slums and unhealthy living conditions, often accompanied by a rapid spread of disease. Furthermore, while these new migrants often found increased employment opportunities as a result of industrialization, they also often faced harsh, sometimes dangerous working conditions and long hours. Child labor was widespread, with children expected to contribute to family’s income. However, the expansion of industrialization and increasing size of the working class also led to the rise of trade unions which, despite significant opposition from governments and employers, were able to secure better working conditions and higher wages for employees.

7.2 Patterns of Industry

Industrialization led to the creation of different economic sectors, and very different patterns of development across the world. For much of the time period after industrialization, there were three economic sectors: primary, secondary, and tertiary. Primary sector activities involve directly getting raw materials from the natural environment. This might include activities such as coal mining, fishing, or farming. Secondary sector activities involve transforming these raw materials into goods. Manufacturing would be considered a secondary sector industry. The tertiary sector involves providing a service to businesses and consumers, such as transporting manufactured goods or providing for their sale to consumers. To understand how these sectors work together, a primary sector activity might be logging. A secondary activity might transform this lumber into a chair. A tertiary sector activity would be a furniture store where the chair could be sold to a consumer.

As industries, and our economic landscape, became more specialized and complex, there was an addition of two more sectors to describe the work we do. The quaternary sector describes work that relates to information technology, such as computing or research. The quinary sector consists of jobs related to high level decision-making, such as government officials and senior managers. Sometimes public services are included in the quinary sector.

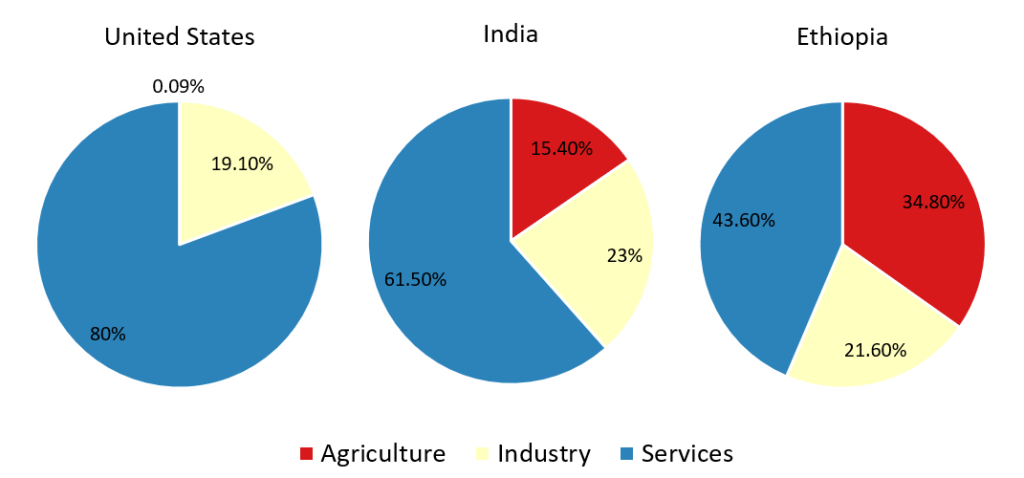

It can sometimes be difficult to differentiate between tertiary, quaternary, and quinary jobs – and in fact sometimes quaternary and quinary activities are considered part of tertiary activities since they are all services – but what is more important perhaps is understanding that countries have a very different mix of these jobs and examining how a country’s employment is structured based on these sectors can shed light on the country’s development and economy as a whole (see Figure 7.2). In general, less developed countries have a greater percentage of their workforce engaged in primary sector activities. As a country becomes more developed, there is generally a shift to more secondary and then to tertiary activities. Think about what career you are currently employed in or are working toward. What economic sector is it in?

Geographers can also examine spatial patterns of where industries are located and why, and again these patterns differ by country and by geographic situation. Imagine you wanted to build a new factory. Where would you build it? Industries are located where the cost of transporting and producing goods is minimized, an idea known as least cost theory. But, where is it going to be least costly? That really depends on what you’re making. Let’s pretend you’re making wooden chairs, to use our example earlier. If you’ve ever worked with wood before or visited a lumber mill, you know that wood is really heavy, and while modern milling techniques can maximize the number of boards we can get from one tree trunk, there is quite a bit of waste in the process. These boards are then cut down to the specifications of your chair design and put together before they can be sold to consumers, again adding some waste of wood into the process. It might make sense, then, to locate close to a lumber mill so you minimize the expense of transporting wood to your furniture factory. The lumber mill itself might locate relatively close to a forest to minimize the expense of shipping heavy logs long distances. Bulk-reducing industries are those where the inputs weigh more than the finished product.

Another example of a bulk-reducing industry is mining. Copper ore, for example, only contains about 0.6% to 1% of actual copper – the rest is waste. Thus, smelting facilities where the valuable metals are extracted from the ore are typically located very close to the mine to reduce the cost of having to transport large amounts of wasted material. Utah’s Bingham Canyon Mine, where copper is mined, is the largest man-made excavation and deepest open-pit mine in the world (see Figure 7.3) and the extracted ore is treated at a smelter a relatively short distance away. Because bulk-reducing industries do just that, they reduce in bulk as they’re worked into more finished products, they tend to locate close to the resources used in their production.

Bulk-gaining industries, on the other hand, are those economic activities where the finished product weighs more than the inputs. Can you think of any examples of bulk-gaining industries? Consider products that have a lot of open space inside. Refrigerators are a good example. The individual components like metal and plastic are relatively easy to ship. However, once you put them together, you end up with a very large, and heavy, product. Soda bottlers are another good example. If you’ve ever worked in a fast food restaurant, you might have encountered boxes of soda syrup. How often do these have to be replaced? Surprisingly infrequently since a relatively small amount of syrup is mixed with carbonated water to make soda. If soda is bottled for sale, the inputs (soda syrup) are relatively light compared to the water it must be mixed with, but water is available anywhere. So where might these industries decide to locate? In general, it would make sense to locate closer to consumers in this case because the weight of the finished product is so high.

Other industries might make a product that is for a single market. Imagine you’re making parts for a new car. It would make sense to locate as close to the automotive factory as possible. Many of these industries also practice what’s known as just-in-time delivery. Just-in-time delivery is exactly what it sounds like – goods are delivered just in time to be used and only the goods that are needed are produced. This eliminates costly inventory and it also eliminates the possibility of having items that will not be able to be sold (perhaps with our car example, if a new model comes out that doesn’t use that particular part.) A challenge with just-in-time delivery is that the elimination of inventory makes the manufacturer more vulnerable when shocks to the system happen. If there is a natural disaster, weather closing, or labor shortage, there is no extra inventory available to fulfill customer orders. Still other industries might make perishable products, and in these cases, it would be beneficial to locate closer to consumers to reduce spoilage.

Similar industrial developments have also tended to cluster together, a process known as agglomeration. What benefits would industries have from clustering together in a single area? Related businesses can reduce costs by sharing facilities or services, reducing transportation costs as complementary businesses seek to locate in close proximity, and take advantage of a large labor market. One example of agglomeration might be large shipyards (see Figure 7.4), which often have related firms like engine building facilities and steel mills located in close proximity. Another example, which you may be more likely to have come across, is a shopping mall. Unlike shipyards, the businesses located in shopping malls are not necessarily related, but they benefit from agglomeration because it gives them access to a larger market of consumers. You might have gone to the mall for some shoes, for example, and then decided that it was time for a pretzel. Clustering is not always beneficial, however, and deglomeration, or dispersal, can occur if rent becomes too expensive or an industry becomes over saturated in an area and there are no longer enough consumers to support all of the businesses located there. Shopping malls can similarly be an example of deglomeration as many urban shopping malls have closed as consumer spending habits have shifted.

As industries expand, they can also take advantage of economies of scale, where a company is able to decrease the cost per unit of output as it grows. How does this work? Imagine, for example, that you wanted to build a simple wooden chair. What supplies would you need? If you didn’t already have carpentry as a hobby, you’d need to likely buy saws and woodworking tools in addition to wood. The cost of this one chair would be quite high. What if you got quite good at it and wanted to make five chairs? The cost to produce each chair would go down. Larger operations and facilities would have additional overhead costs and require additional employees and resources, so economies of scale often has an optimum limit, but in general as facilities expand, they are able to take advantage of their size and reduce the cost of production.

In addition to situational factors, site factors are also important components of industrial location and these include land, labor, and capital. Essentially, these factors relate to the costs of production inside the plant itself. Labor-intensive industries are those where a high proportion of expenses are spent on wages paid to employees. This is not to say that employees make a high wage in labor-intensive industries, but rather that wages, compared to other costs of production, represent a considerable expense. What industries would you consider to be labor-intensive? The textile industry is a good example. Sewing and other tasks within textile production is best done by people, as opposed to robots or some automated method, and it requires a lot of people to manufacture textiles on a large scale so this is considered labor-intensive. The cost of land can be a considerable expense when opening a new factory, but in areas where land is plentiful, an industry might consider other features, such as proximity to a low-cost energy source like hydroelectric power. Capital costs can similarly be considerable when building a new facility. Government or finance industry initiatives to try and lure new developments can help reduce capital costs.

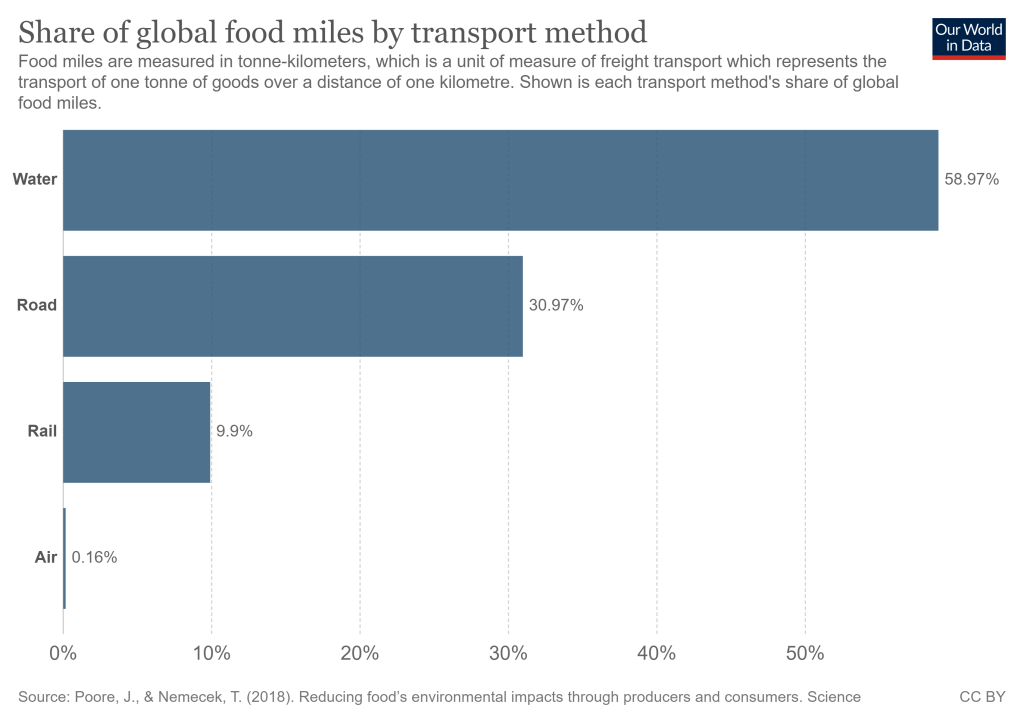

But once you decide on a location for your industry, how do you actually get your product to consumers? Industries transport goods by essentially the same ways we could travel: boat, rail, truck, or air. Generally, a company seeks the cheapest option, but that also depends on the good itself. For example, it would be cheaper, in theory, to ship asparagus by boat since this is generally a lower cost delivery method per mile. But asparagus is highly perishable and so very little of it would be edible by the time it reached its final destination. With a few exceptions, like asparagus and some berries which are sent by air, most food is transported by boat (see Figure 7.5). In fact, the majority of goods transported worldwide are transported by ships.

Commonly, shipping containers are used as they provide a standardized way to transport a large amount of goods a long distance. Shipping containers can be efficiently stacked on large cargo ships and then moved to trains or trucks. Where goods transition from one transportation method to another is called a break-of-bulk point. Break-of-bulk points, as the term implies, break down bulkier cargo deliveries into smaller units. This is where a large container ship offloads the individual containers, perhaps to the back of a truck which can then take the goods to the next destination (see Figure 7.6). The next time you get a package in the mail, see if it has a return address on it or is stamped with its location of origin and consider the journey that product took to get to you – and why the production facility was located at that particular place.

7.3 Measuring and Analyzing Development

Industrialization dramatically changed our human landscape and spurred considerable development, but this development was not evenly distributed. How do we measure and compare development across our world? First of all, when we say “development,” what do we actually mean? Often, people equate development with economic development, such as the level of income or industrial output. Gross domestic product, or GDP, is one way to measure a country’s economic development and it was commonly used historically. GDP measures the amounts of goods and services produced within a country in a given year. Can you think of any limitations of measuring GDP? What about goods and services that are produced for a country but not within a country, such as goods or components produced overseas by an American company? Gross national product, or GNP, includes the value of the national output produced by a country, just as with GDP, but also includes investments made by residents and businesses both within and outside of a country. Gross national income, or GNI, is perhaps the most common measure of economic development today. GNI includes the total income earned by residents of a country regardless of whether that income is earned domestically or abroad. The World Bank classifies a country’s level of development based on its GNI, and in general GNI does tend to correlate with other areas of development within a country. One statistic you may come across is “GNI per capita, PPP” and this simply means the gross national income of a country per person in terms of purchasing power parity, how much a country’s currency can buy based on an international benchmark (which accounts for the fact that goods and services have different prices in different countries.)

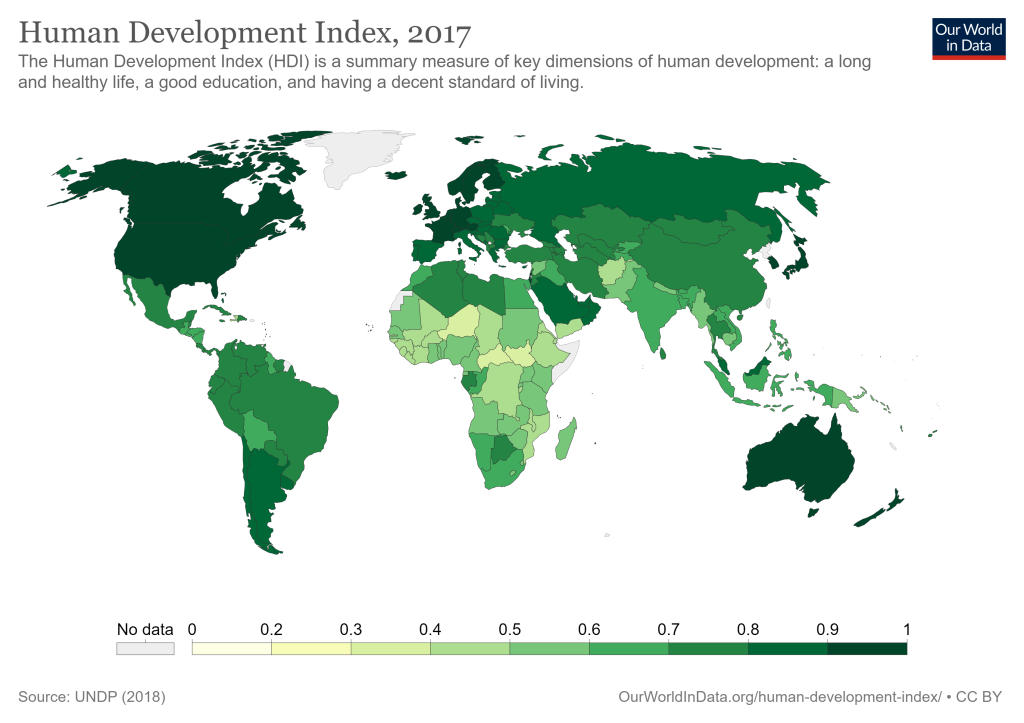

But is income the only way to measure a country’s level of development? What else could be included? What about social factors, such as education and literacy? And what about measures of health, like life expectancy? One of the most common measures of development is the Human Development Index, or HDI. The Human Development Index is a composite statistic created by the United Nations to measure a country’s level of development. By “composite statistic,” we mean that HDI takes more than just income level into account. Rather, HDI consists of life expectancy, education (measured as mean years of schooling completed and expected years of schooling upon entering the education system), and per capita income and creates an index of a country’s development, with a maximum score of 1.0 and a minimum score of 0 (see Figure 7.7). The HDI is useful in comparing countries as well as grouping them based on their level of development. According to the UN’s 2020 report, Norway had the highest HDI at 0.957. The United States was ranked 17th with an HDI of 0.926. Niger was ranked the lowest (189th) with an HDI of 0.394.

Does HDI paint a complete picture of a country’s development, though? What information does the HDI miss? Remember, HDI, like GNI, is an aggregate measure of an entire country’s level of development. It does not include issues like poverty or inequality. There can be significant regional variations of economic development within a country. For example, in 2019, the poverty rate for the entire United States was 10.5 percent. In Mississippi that same year, however, it was 19.6 percent while in New Hampshire, it was 7.3 percent. These aggregate statistics can also miss racial differences. In South Africa, for instance, nearly half of black South Africans are below the poverty line compared to only 1 percent of white South Africans.

HDI also doesn’t account for disparities by gender. There are other statistics that measure these factors, including the Gender Inequality Index, or GII. GII is similar to HDI in that it is a composite index, which again allows for relatively easy comparison of country-level data. The GII essentially measures the loss of potential development within a country that results from gender inequality. It considers reproductive health, empowerment, and labor market participation. In every single country in the world, there is gender inequality, but the situation is slowly improving in most countries. Switzerland had the lowest GII in 2019, meaning it had the lowest levels of gender inequality. Mothers in Switzerland, for example, are given 14 weeks of paid maternity leave, as mandated by the Swiss Constitution. In 2019, the Swiss government also approved a proposal requiring better representation of women on the boards of publicly traded companies. Yemen was ranked the lowest in terms of GII in 2019 with an index of 0.795. The United States was ranked 46th with 0.204. This inequality comes at a significant economic cost with research by the U.S. Treasury Department showing that achieving gender equity would add between $2 trillion and $4 trillion to the U.S. gross domestic product.

It is clear that economic development has occurred unevenly, both in terms of disparities within a country and between countries. There are several key theories that can help explain these spatial variations. American economist Walt Whitman Rostow proposed in 1960 that economic development occurs in five basic stages, commonly referred to as Rostow’s Stages of Economic Growth. Each country, according to Rostow, is in one of the following stages of growth, and each stage varies in length:

- The traditional society: characterized by hunting and gathering activities or subsistence agriculture; primary sector activities

- The preconditions for take-off: shift to commercial agriculture; increasing spread of technology and infrastructure improvements

- The take-off: increase in urbanization; secondary sector activities expand

- The drive to maturity: industries diversify; transportation and social infrastructure develops

- The age of high mass-consumption: highly urban society; widespread consumption of high-value consumer goods

While Rostow’s model fits the historical development pattern of Europe and the United States quite well, in other geographic locations such as across much of Asia and Africa, the model seems to be less applicable. Furthermore, not every country has the same resources and may not have a long period of industrialization, perhaps shifting from more primary sector activities to service sector activities like hospitality or banking. Colonization, too, dramatically changes how rapidly a country is able to develop and how easily it can invest in its infrastructure.

Another theory that seeks to address the persistent underdevelopment of some states is dependency theory. Dependency theory is the notion that resources generally flow from peripheral countries to core countries, enriching the economies of the core countries at the expense of peripheral countries. Dependency theory essentially holds that it is to the core country’s advantage to keep the peripheral countries in the periphery. Why is that? If core countries can limit the economic advancement of peripheral countries, they can buy goods and services from these countries more cheaply. This theory is counter to Rostow’s model, viewing underdeveloped countries as not just in an “earlier” stage of a development model, but rather having a weaker position in the world economy that limits development. Countries in the periphery are often considered to be commodity dependent, meaning that they rely heavily on exporting basic products, which then makes them vulnerable to international markets and price fluctuations.

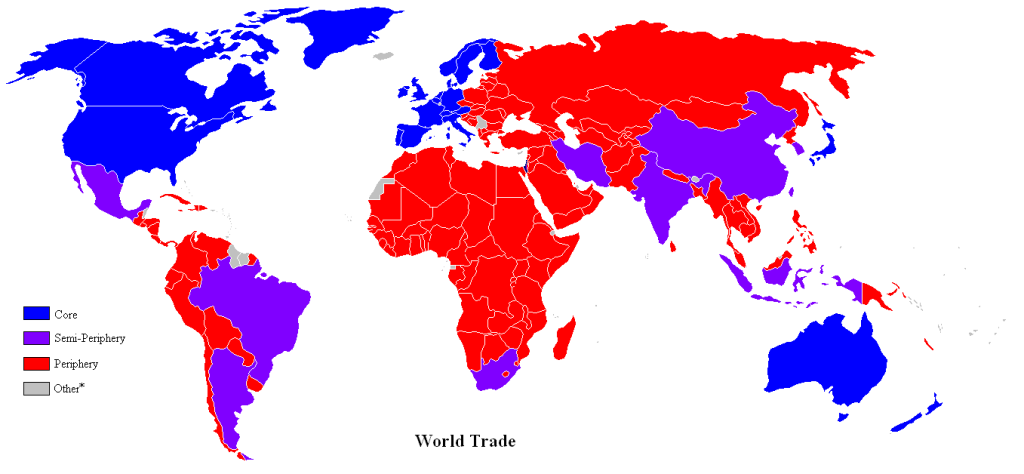

World Systems Theory, developed by sociologist and historian Immanuel Wallerstein in the 1970s, builds upon dependency theory and divides the world into three categories – the core, periphery, and semi-periphery – based on economic development and political power (see Figure 7.8). According to this theory, the world is increasingly interconnected, and while there is an acknowledgement that peripheral countries are exploited by core countries, World Systems Theory notes that peripheral and semi-peripheral countries do see some benefits as result of trading with core countries. Furthermore, World Systems Theory, as the name suggests, views countries as part of a larger world economy. According to Wallerstein, just as within a typical capitalist economy, where there are differences in social class and the ownership over means of production, these ideas can be applied to a broader scale, with core countries controlling the major means of production and performing higher-skilled tasks while peripheral countries own very little and provide lower skilled labor.

All three models present different, generalized perspectives on global uneven development. They are often criticized, though, for being overly general and overlooking the unique geographic situations and histories of particular countries as well as regional differences or struggles within countries. As a human geography student, rather than ascribe to one particular theory exclusively, it might be more helpful to use these theories as lenses to help analyze and critically examine the world. How have countries developed historically? In what cases did a country clearly pass through progressive stages of development as in Rostow’s model? In which cases did a country shift around, perhaps following one economic system before shifting to another? Which countries tend to dominate the global economic system, and which countries have relatively little power? How would you explain why these differences exist?

7.4 Global Economics and Trade

The global economy has become increasingly interdependent and these global connections have led to the creation of a number of new organizations and trading relationships. Perhaps the most well-known is the World Trade Organization (WTO). The WTO was formed in 1995 and it regulates and facilitates international trade, providing a framework for negotiating trade agreements. Generally, these agreements seek to promote free trade, and indeed the WTO has significantly contributed to the reduction of trade barriers and an increase in global trade. The WTO’s approach to trade is often characterized as neoliberalism. Neoliberalism is an ideology that promotes free market competition and views economic growth as critical to human progress. Under neoliberalism, goods and capital should be allowed to flow freely, with only minimal government intervention.

As mentioned, though, the world’s resources are not distributed evenly, and some criticize the WTO’s approach as contributing to a widening gap between rich and poor countries. Promoting neoliberal trade policies early in a country’s development can make it susceptible to commodity dependence and an over-reliance on primary sector industries that can be difficult to disentangle from. Furthermore, even once a country begins to industrialize and diversify, it can be difficult for them to compete with more advanced countries in the global core. Others argue that the reduction in global tariffs contributed to wage and job loss in the United States as firms moved their production overseas.

In general, our entire economic system and the production of goods and services is far more fluid than at any previous time in human history. In early industrialization, we were often limited by local resources and labor markets. Today, though, multinational firms may have facilities all over the globe, importing resources from one area, putting some components of a product together using low wage laborers in another location, and finishing the product in an entirely different place. This portioning out of business activities is known as outsourcing. Often, companies outsource to other countries where labor rates, in particular, are lower. Sometimes, activities which are detrimental to the environment are also outsourced to areas where environmental regulations are not as strict.

A number of other trade organizations have emerged that have further fostered global cooperation and contributed to globalization. One of the founding principles of the European Union was the goal of free trade across its member states, and the EU itself is a member of the World Trade Organization. Mercosur, or the Southern Common Market, is a South American trading organization promoting free trade and the fluid movement of goods and people across its member states, which include Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay. The United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA), which replaced the former North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), is a free trade agreement between Canada, the United States, and Mexico.

Some trade organizations were created not as regional partnerships but with a focus on specific goods or resources. The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, more commonly known as OPEC, was founded in 1960 among six of the world’s top oil-producing states. It now has 13 member states all over the world, including Algeria, Venezuela, Angola, and Iraq. OPEC is highly influential in the global oil market and OPEC exports account for over half of global oil trade. Oil prices, like other resources, are determined by global supply and demand. If countries over-produced oil, then prices would drop. Similarly, if there was a huge spike in demand without an accompanying increase in supply, prices would increase. OPEC sets production targets for its member countries and through these targets, is able to stabilize the market price of oil, limit over supply, and ensure steady profits.

Let’s imagine that a country wanted to increase its development and global trade but had limited financial resources or was experiencing economic hardships. How could a state fund investments in its infrastructure and improve its economic position? Private citizens or businesses could ask a bank for a loan but states often turn to the International Monetary Fund, or IMF, an international financial institution. The IMF aims to promote global economic growth and stabilize the world’s financial markets as well as provide loans to countries who may be experiencing economic distress. In cases of public health disasters, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, the IMF provides debt relief grants for low income countries to be able to better address crises.

Connecting with World Systems Theory, one of the most significant criticisms of the IMF is that it reflects, and often reinforces, the political and economic power imbalances that exist in our world. In addition, IMF loans come with specific conditions that must be met to ensure a country repays its debt, and generally these conditions include increased privatization, instituting more liberal trade policies, and accepting foreign investment. Historically, these lending conditions were enforced through Structural Adjustment Programs, or SAPs, a set of guidelines and policies aimed at improving a country’s financial situation. In practice, however, SAPs often reduced government funding for social programs and a country’s most vulnerable citizens, instead focusing on spending on production and trade, activities which generate more economic benefits in the short-term but may not address underlying infrastructure, healthcare, or education needs within a country. Today, the IMF uses a system known as Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers, ideally a process driven by the country requesting a loan rather than the IMF, but in practice, containing much of the same policies promoted through Structural Adjustment Programs.

The increase in interconnectedness of our global economy has, in many ways, contributed to greater global prosperity. However, this increasing interdependence also means that what happens in one country can have a significant impact on another. The Great Recession of 2007-2009, for example, was very much a global economic decline that began with the bursting of the United States’ housing bubble. This then triggered a financial crisis in Greece as a result of its significant government debt and the country received massive bailouts from the IMF and other international organizations in order to stabilize. In essence, the increasing interconnectedness of our world means that when one of us does well, we all benefit (though we don’t experience equal benefits), but when one is struggling, we all feel the effects.

The impact of economic globalization is also evidence on our landscape. In peripheral and semi-peripheral countries, industrialization and globalization has led to the creation of special manufacturing zones. In China, for example, Special Economic Zones (SEZs) have been established that allow free market economic policies that are more attractive to foreign investment and businesses. If you examine a map of SEZs (see Figure 7.9), what do you notice about their location? SEZs are located along China’s coast to better facilitate exports. Special Economic Zones where free trade is promoted aren’t limited to China, however. Today, there are SEZs all across the world including Latin America and Asia and the first was actually established in Ireland.

7.5 Sustainable Development

We’ve come a long way as a human race and the way we live and work continues to evolve. The process of industrialization and development has not always been easy, though, and the negative effects have been significant. So, is it possible to develop in a sustainable way? And what does that even mean? Sustainable development broadly refers to development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. Essentially, it is considering the long-term impacts of development rather than just short-term gains. The notion of sustainable development is often applied to environmental impact, and while this is an important component of sustainability, true sustainable development also considers social and economic impacts.

Consider, for example, how we generally finance development. Large corporations and businesses are more easily able to secure loans from financial institutions. But what about smaller businesses or even individuals who are looking to expand or enter a market and need only a small sum of money? Microfinance broadly refers to financial services that target individuals and small businesses. Part of microfinance is microlending, offering small loans to lower income clients. Microfinance, though, is not limited to loans and can also include smaller savings and checking accounts, microinsurance programs, and payment systems. For women in particular, microfinance can provide a much-needed way to advance economically in areas where there might not be access to traditional banking and financial services, or in cases where banks would be unwilling to provide such a small loan to a household with no assets. Rates of repayment on microfinance loans are extremely high.

As consumers, we have an important role in shaping global development, though we might not often realize it. Everything we buy is essentially a vote that we support the production of that item and the way it was produced. When we buy clothing produced in a textile mill that has poor working conditions or even employs slaves, we are saying that we support that system continuing – and over $120 billion of the garments imported by more developed countries in 2018 were at risk of having been produced by modern slaves. When we buy food like coffee from suppliers who pay farmers barely above or even sometimes below the cost of production, we’re saying that we are okay with that arrangement if it allows us to pay lower prices.

So what if we don’t actually support those kinds of unsustainable developments? Are there any alternatives? One solution is known as fair trade, which aims to do just that – help producers in developing countries create more sustainable and equitable trade relationships. Fair trade seeks to ensure that producers are paid a fair wage and have decent working conditions, including a ban on forced labor and child labor. It also aims to make sure that products are produced in environmentally sustainable ways and that producers have a greater voice the production process. There are a number of organizations that provide fair trade certification, and while the price of fair trade products might be higher, proponents argue that these higher prices provide more sustainable development for producers and more accurately reflect the product’s true cost.

The United Nations also developed a set of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015 with the intention of achieving them by 2030. The 17 SDGs are:

- No Poverty

- Zero Hunger

- Good Health and Well-being

- Quality Education

- Gender Equality

- Clean Water and Sanitation

- Affordable and Clean Energy

- Decent Work and Economic Growth

- Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure

- Reducing Inequality

- Sustainable Cities and Communities

- Responsible Consumption and Production

- Climate Action

- Life Below Water

- Life On Land

- Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions

- Partnerships for the Goals

While significant progress had been made in reducing poverty worldwide, the COVID-19 pandemic contributed to the first increase in global poverty since 1998. In addition, school closures contributed to a decline in global education as well as access to food, since many young children relied on schools for nutritious meals. Broadly, the world’s poorest and most vulnerable were those hit hardest by the effects of the pandemic.

You’ll notice that these so-called “development” goals really encompass much more than just industry and the production of goods, and this really is a reflection of the fact that development impacts every area of our lives. What we do and how we produce goods has a profound effect on the environment, on our economics, on our broader society to include things like education and healthcare, on how our cities grow and change, on where our population is located, on poverty within our countries and around the world. Our human landscape is shaped by our development practices.

We are more connected to one another than ever before, and these connections are clearly apparent as we examine global industry and development. But because of this increased connectivity, we also have new opportunities to collaborate and innovate. The COVID-19 pandemic’s rapid and wide-reaching spread illustrates how interconnected we are in our modern society, but the development of the vaccine also provides an example of the value in harnessing these global connections as scientists and researchers were able to share knowledge and learn from one another on a scale that has never been seen before. What other solutions could we tackle with the same spirit of openness and global cooperation? How can we leverage these connections to find new ways of sustainably developing and improve our world? Our story is your story. What you want for your life and your work, how you view the environment and Earth’s resources, how you view our role in the global economy, all of these will shape the jobs of the future, what we produce, and how we produce it. What does our future hold? It’s up to you.

a home-based manufacturing activity, such as weaving

a period of transition to new manufacturing processes beginning in the United Kingdom from the mid-1700s to the mid-1800s

an economic activity that involves directly getting raw materials from the natural environment

an economic activity that uses a raw material to create a finished good

an economic activity that provides a service to businesses and consumers

an economic activity that relates to information technology, such as computing or research

an economic activity related to making high level decisions

an economic activity where the inputs, or raw materials, weigh more than the finished product

an economic activity where the finished product weighs more than the inputs

a system of producing goods only as needed in order to reduce inventory and align with the buyer's needs

a clustering of economic activity, such as when similar industries locate near one another

the cost advantage gained by industries as they grow in scale and are able to decrease the cost to produce each unit

a location where cargo arriving in bulk is broken up into smaller units to transport elsewhere

or GDP, a measure of the amounts of goods and services produced within a country in a given time period

the value of all goods and services produced by a country and the value of all of the overseas investments by its residents and businesses

or GNI, the total income earned by residents of a country

or HDI, a composite statistic created by the United Nations to measure a country's level of development

or GII, a measure of gender disparity created by the United Nations that uses reproductive health, empowerment, and labor market participation to measure the loss of achievement in a country due to gender inequality

a theory of uneven development that holds that resources generally flow from peripheral countries to core countries

an ideology that promotes free market competition

contracting out a portion of a business to another party, which might be located in another country

financial services that target individuals and small businesses on a smaller scale than traditional financial institutions