4

Learning Objectives

- Explain the challenges of defining a state

- Analyze state boundaries and the various shapes of states

- Describe the various forms of government found in the world

- Identify the key modern political challenges

- Discuss the challenges of maintaining state unity

How many countries are there in the world? It’s a question geographers are often asked, but it’s not as easy to answer as you might think because the answer depends on who you ask (or, more accurately, which country you ask). First of all, the term “countries” is generally used to refer to sovereign states. There 193 sovereign states that are members of the United Nations – but another two states that are non-member observers: the Holy See (which oversees Vatican City) and Palestine. A number of states are recognized by some countries but not others, including Taiwan, Kosovo, and the Republic of Cyprus. Still other ethnic groups wish to create their own, independent states but do not currently have autonomous territorial control, to include the Kurds, an ethnic minority of around 30 million people in Iran, Iraq, Syria, and Turkey, and the Yoruba, numbering around 35 million people, spread across Nigeria, Benin, and Togo. So why is even deciding which regions and ethnic groups should be sovereign so difficult? What does sovereignty mean? And do state boundaries even matter anymore in a world that has become so increasingly globalized? This chapter investigates these questions through a discussion of political geography.

4.1 Understanding and Defining States

So to begin with, what is a “state” anyway? For geographers, the term state refers to an organized territory led by a government that has control over its domestic and foreign interests. Sovereignty broadly refers to the authority of a state to govern itself within a territory and levels of sovereignty can vary. A state might give up some of its sovereignty in order to form a partnership with another country. States might grant autonomy to particular regional areas within the state – but could similarly rescind that autonomy as well. Defining states is further complicated in the United States because the U.S. calls its regional entities “states,” such as Florida, New York, or Idaho, and Americans often refer to places like Germany, Angola, or Bolivia as “countries.” In other parts of the world, these subnational entities are often referred to as territories or provinces.

In the 1940s, the world contained only 50 states. Now, as discussed, the United Nations has almost 200 member states. Understand, then, that the idea of a “state” is relatively new. Previously, we had various world empires that controlled large tracts of domestic territories as well as colonies abroad. In other areas, like Africa before colonization, you had kingdoms in some areas and in others, various tribal groups controlled different stretches of land and resources.

So how did the idea of states develop? States originated in Mesopotamia (see Figure 4.1) around the same time as agriculture. They began as city-states, which were sovereign cities that controlled the surrounding territory. Many of these city-states later evolved into larger empires. Why did people settle in the area of Mesopotamia? Do you notice any sources of water nearby? Remember, early cities did not have irrigation systems, and thus needed sources of freshwater in order to survive. The ancient city of Ur dates back to 3800 BCE and was located near the mouth of the Euphrates River. The city was the largest city in the world for some time, with a population of around 65,000 people, houses clustered in neighborhoods, and a street system.

Other ancient states began to emerge. Egypt developed as an empire alongside the banks of the Nile. Ancient Greece also developed as city-states, spreading from its hearth by Alexander the Great to other areas including Northern Africa and South Asia. In Europe, the formation of the state began after the dissolution of the Roman Empire, which extended into such areas as Europe, North Africa, Southwest Asia, and Spain. Europe became fragmented because it was ruled by kings and nobles struggling for power. These fragmented areas were governed by local rulers. Some particularly powerful rulers would eventually come to lead large, multi-ethnic empires, such as the Austrian Empire, the Portuguese Empire, and the British Empire.

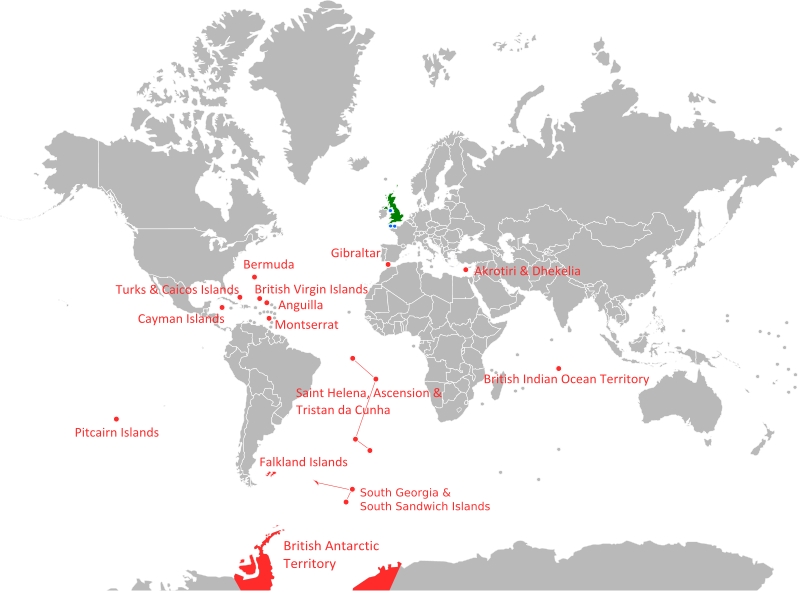

With the expansion of various empires, particularly in Europe, came the era of colonialism. A colony is a territory that is ruled by another state. The Colonial era began in the 1400s, and the United States, of course, began as a colony of Great Britain. Do any colonies still exist today? While many colonies have since gained independence, there is still a significant number of territories, colonies, and possessions around the world today. Chile controls Easter Island, for example. France controls the northern portion of the beautiful Saint Martin island (the Netherlands controls the South.) Greenland, though autonomous, is actually part of the Kingdom of Denmark. Britain controls a number of overseas territories including Grand Cayman and the Pitcairn Islands (see Figure 4.2). And what about the United States? The U.S. controls a number of territories including Puerto Rico, American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, and the Virgin Islands. Do you notice any similarities in these territories? Consider their names and locations. The most populous remaining colony is Puerto Rico (which is technically a commonwealth). Its 4 million residents are US citizens, but do not participate in US general elections. The least populated is Pitcairn Island with 43 people, most of whom are descendants from mutineers from the HMS Bounty.

Why did states engage in colonial activities? One simple way of remembering is the “3 G’s”: God, gold, and glory: missionaries established colonies to promote Christianity; colonies provided resources that helped the economy of imperial states; and states considered the number of colonies to be an indicator of relative power. But why do colonies persist today? If you notice maps of territories, you’ll find that most territories in the world today are islands. In some cases, colonies are of strategic military importance, as is the case with Guam, which is home to a number of large military installations and has a strategic location in the Pacific. In other cases, the reasons are primarily economic – either benefitting the colonizing country, the colony itself, or both. French Guiana, for example, on the Atlantic coast of South America is a territory of France and, as such, is part of the European Union. It is also home to the Guiana Space Center which is a major launch site for the European Union and provides a considerable amount of economic development and jobs for the territory.

As more powerful states emerged, sometimes a region was caught in between these more powerful states. These are known as shatter belts and these states often experience greater instability and fragmentation as a result of their strategic position. Many of the states of Eastern Europe might be considered part of a shatter belt since they are pinned between Russia and Western Europe, who have historically been at-odds. Mongolia, similarly, might be considered part of a shatter belt region since it is positioned between Russia and China.

Many of the states we commonly know today are actually relatively young. Some only fairly recently achieved independence, which is the case for a number of former colonies like Kenya (declared independence from the United Kingdom in 1963) and Morocco (achieved independence from France in 1956). Other states were fragmented into various city-states or smaller territories and later unified. Italy, for example, was home to a number of different states including the Kingdom of Naples, the Duchy of Savoy, and the Republic of Venice before it was unified into a single state in the late 1800s.

As states developed, some boundaries were relatively homogeneous in terms of their cultural, ethnic, and linguistic composition. These are known as nation-states. We’ve already learned what a state is, and how complex the notion of a “state” really is, but what is a nation? A nation refers to a group of people who have a homogeneous cultural and ethnic identity. A nation-state is thus an independent state that is also culturally and ethnically homogeneous. A number of nation-states still exist in the world today. Poland, for example, is almost entirely populated by ethnic Poles (around 98 percent.) Japan similarly is majority ethnically Japanese (over 98 percent as well), but is also home to the indigenous Ainu and Ryukyuan people. These states can thus be considered nation-states.

Increasingly, though, states have become multi-ethnic, home to a variety of ethnic and cultural identities. The United States, for example, is home to people of many different ethnicities and nationalities. An American might be the descendent of Polish, Italian, and Czech immigrants (like me!), for example, or have Native American ancestry or be descended from Africans who were forcibly brought to the American colonies as slaves. In fact, many countries that we might think are nation-states are actually multi-ethnic, including India, Russia, and China. And, as mentioned, even states with a homogeneous ethnic identity are still home to other minority ethnic groups, even if they are quite small.

Do all nations have states? Consider smaller ethnic groups that may not be the majority in any territory. Or ethnic groups within larger multi-ethnic states that do not have their own sovereignty. There are a number of nations that are not self-governing and these are referred to as stateless nations, or ethnic groups who do not possess their own state and are the minority in every state it occupies. Some stateless nations are quite large, such as the Kurds mentioned earlier. In addition, there might be several stateless nations within a state. Spain, for example, is home to both the Basque and Catalan ethnic groups, among others, who have pushed for greater autonomy and independence. In other cases, some ethnic groups that were previously considered stateless nations later broke away from a larger, multi-ethnic state and became a nation-state, as in the case of many of the nations that comprised the former state of Yugoslavia. This desire for autonomy and sovereignty is a key distinction between the concept of a stateless nation and simply an ethnic group found within a state.

The question of whether or not ethnic groups should have control over their own territory is known as self-determination. The question of self-determination can be tricky. In some cases, the boundaries of a former empire coincide fairly well with the modern ethnic landscape and state boundaries are appropriate. In other cases, an empire might have included minority ethnic groups and their homelands. Sometimes, these groups have been able to achieve independence. In other cases, they remain part of another state and may argue that they have a right to self-determination.

In still other areas, a state might be independent but still subject to foreign involvement or influence. Neocolonialism, unlike colonialism, is a form of control using economic influence or indirect political control rather than direct military or political authority. With neocolonialism, foreign companies rather than countries control an area’s resources either through buying land directly or through investment in the region. Proponents of neocolonialism and foreign investment see these activities as helping to bring economic development to impoverished regions. Critics, however, point out that trade deals are often skewed to the benefit of wealthier countries, with poorer countries only receiving a small fraction of what their raw materials are worth. Furthermore, it can be difficult to break free from neocolonialism. If the people in a colony want to break free from foreign control, they could declare independence. But how would you declare independence from a company? Or renegotiate trade deals that disadvantage poorer countries? Thus the notion of “independence” is much more complex than it might initially appear.

4.2 Political Boundaries

If you look at a world map, you’ll notice that the boundaries between states, as well as the size and shape of states, varies widely. Chile, for example, is really long and thin while Uruguay is shaped a bit like an egg. Much of the boundary between the United States and Canada is a straight line, while the boundary between France and Spain is all squiggly. Why is there so much variety?

In addition, how much the boundaries matter is also highly variable. In some areas, the boundary between states is very much a well-defined border, as Figure 4.2 displays. In other cases, the boundary is much more porous and might be as easy as crossing to the other side of the street (see Figure 4.3). In still other cases, the boundaries between states are still contested. Western Sahara, for example, is a disputed territory that is partially controlled by the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic and partially administered, and claimed, by Morocco. There is still a dispute over the Kashmir region, which is claimed by both India and Pakistan, as well as partially by China. Thus, when you look at the boundaries on a map, sometimes the solid lines we see mask underlying conflicts and debates.

Geographers refer to a number of different types of boundaries between states. Broadly, boundaries can be characterized as either physical, that is, corresponding with features on the natural landscape, or cultural, connected with characteristics of the human landscape. Physical boundaries might follow the curve of a river, for example, or drawn along a mountain chain, as is the case for the boundary between Nepal and China. This can present some challenges, however. Do you draw the line from the tops of the mountains or along the valley? If a boundary crosses a body of water, how do you ensure its protection if two countries share it but disagree on how it should be managed?

Cultural boundaries are often created on the basis of ethnic, linguistic, and/or religious identity. Lithuania, for example, is almost entirely comprised of the Lithuanian ethnic group. Here, too, there can be challenges though, since virtually no country is exclusively one ethnic group, and ethnic groups often overlap across international borders. Furthermore, some countries may appear to be ethnically homogeneous, but this modern homogeneity might mask ethnic cleansing that has occurred.

We can also characterize boundaries based on how they were developed and how they have changed over time. Antecedent boundaries were created before the modern human landscape developed. Many physical boundaries, like mountains or large rivers, are also antecedent boundaries because they divided indigenous groups from one another and presented formidable obstacles. In some cases, boundaries develop over time as an area develops, and these are known as subsequent boundaries. Wars, for example, might cause a territory to shift control from one country to another. Consequent boundaries are similar in that they developed later but were specifically drawn in order to separate groups based on cultural features such as ethnic, linguistic, or religious differences. The boundary between India and Pakistan, for example, is a consequent boundary created to divide the predominantly Hindu state of India from the predominantly Muslim state of Pakistan. Superimposed boundaries are exactly what they sound like – these were boundaries superimposed on the landscape by colonizers or conquering forces that often ignored underlying cultural differences or resource distributions. Much of the boundaries in Sub-Sahara Africa were superimposed, created by European powers and the United States at the Berlin Conference of 1884. In other cases, there might be the remnants of a boundary that no longer exists. The Berlin Wall, for example, used to divide West Berlin from the surrounding area of East Germany. These are known as relic boundaries. Finally, geometric boundaries are perhaps the easiest to identify – these are drawn using straight lines, such as lines of latitude or longitude. Much of the border between Algeria and Mali, for example, is geometric and runs in a straight line from the northwest to the southeast.

While these terms can help us begin to uncover how and why borders were created between states, note that as with the other terms we’ve learned like “state” or “sovereign,” the reality is much more complex – and interesting – than it might appear. Furthermore, these terms are highly dynamic and often overlap. For example, the border between Algeria and Mali that was just mentioned could be characterized as geometric. But it also coincides with the Sahara, so it is a physical boundary. It was developed by France, which conquered and colonized Algeria in the mid-1800s, so it is superimposed. Thus, as with all concepts in Human Geography, it is important to dig deeper and recognize the complexity of our human landscape.

Just as the boundaries between states vary, the size and shapes of states vary as well and we can characterize states as one of five basic shapes. Compact states are states where the distance from the center to any point along the boundary is almost the same and these states are highly efficient to govern and to develop infrastructure. Why might this be? In a compact state, everything is, well, compact. This means that if the capital is located near the center of the state, it will be able to easily connect with the surrounding regions. Similarly, it would be easier to build infrastructure such as roads and telecommunications without having to connect fringe regions. Cambodia is an example of a compact state (see Figure 4.5). What other compact states can you identify on a world map?

Elongated states are quite different. These states are very long and narrow. This can make infrastructure, particularly transportation, difficult. Furthermore, areas that are significant distances from the capital can be isolated which can present challenges. Chile is perhaps the most common example of an elongated state (see Figure 4.6), but there are others such as Norway and the Gambia.

Another type of state is known as prorupted (or protruded). Prorupted states generally have a fairly compact main territory, but then have a long extension protruding from it. What challenges might this pose? As with a compact state, the main territory might have the possibility for efficient government control and infrastructure development. But as with elongated states, there might be challenges accessing or controlling the fringe areas along the protrusion. Why would this state shape even exist? Well, consider why the protrusion would be created. Perhaps it exists to connect the main territory to distant resource, like water. Or, a protrusion might naturally develop along a peninsula. Namibia is a good example of a prorupted state. Its Caprivi Strip connects the main territory of Namibia to the Zambezi River and was superimposed by Germany when Namibia was a German colony in order to give them access to the river.

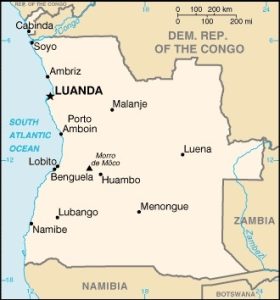

Fragmented states are just that – they are fragmented into multiple parts. Sometimes, water divides the territory, as in the case of many island states like the Philippines and Fiji. In other cases, land in other states might divide noncontiguous pieces of territory. This is the case for Russia (Kaliningrad, located on the Baltic Sea between Lithuania and Poland, is separated from the rest of the state of Russia) and Angola (the Cabinda Province is separated by the Democratic Republic of the Congo) (see Figure 4.7). The United States is fragmented for both reasons – with Hawaii separated by water and Alaska separated by Canada.

Finally, we have perforated states. These are states that completely surround another state. As you can imagine, these types of states are uncommon. Perforated states are often confusing for students, so note that the perforated state is not the state within another state (like Lesotho, which is a compact state.) Rather, perforated states are those that surround another state. One way to remember might be to consider that if I asked you for a perforated sheet of paper, you’d give me a piece of paper with three holes punched on the side, right? You wouldn’t just give me a pile of punched-out holes. South Africa is a good example of perforated state (see Figure 4.8) as it completely surrounds the state of Lesotho and almost completely surrounds the state of Eswatini (commonly known in English as Swaziland.)

As with characterizing boundaries, defining the shape of states can sometimes be challenging. How long and narrow must an elongated state be to actually be characterized as “elongated”? What if it’s really small – is it compact or elongated then? How large must a protrusion be to be characterized as a prorupted state? Understand that these terms have less to do with precisely defining states in their exact category and are more about understanding that the shape of states has an impact and that we can use these general shapes to help understand what those impacts might be.

We also have boundaries within states. These are known as internal boundaries. These might divide larger states into administrative districts, as with the United States or Canada. Or, they might be used to provide autonomy (or relative autonomy) to sub-regions, as with the case of Scotland, which has limited self-government within the United Kingdom.

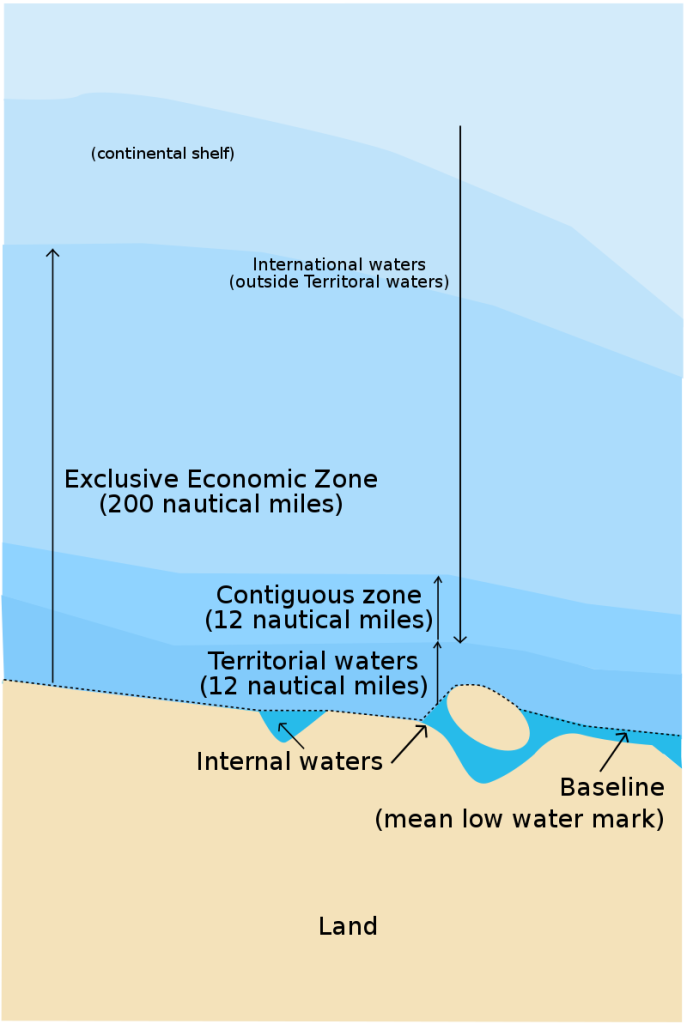

Finally, it might be relatively easy to determine where state boundaries are on land, but how far out does a state’s boundary go when we consider maritime borders? The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) established the boundary zones for international waterways (see Figure 4.9). Essentially, any water body within a country is considered internal waters. Extending out 12 nautical miles from a country’s landmass is considered territorial waters. Here, states are free to set laws, regulate use, and use any resource. Vessels traveling in this zone are given the right of innocent passage, meaning that if it is passing innocently through this zone (i.e. not trying to attack or representing a threat to state security), it is allowed to pass through. Extending out an additional 12 nautical miles from the territorial waters is the contiguous zone. Here, a state has some control, but only over customs, taxation, immigration, and pollution laws in order to protect its territorial waters. Finally, extending out 200 nautical miles from the edge of the state’s landmass is known as the exclusive economic zone (or EEZ). Here, a state has a right to any natural resources. Beyond the EEZ is considered “international waters,” sometimes called the “high seas.,” where no one state has control but there have been a number of global agreements covering a variety of activities such as the dumping of waste.

The series of agreements over the jurisdiction of our world’s waterways set off a scramble for control of the world’s oceans, because if a country claimed control over even a miniscule island, that island could offer control of a 200 nautical mile radius around it and, perhaps more importantly, whatever resources were found in or beneath the waters such as oil. This is another critical reason why so many of the colonies still present in the world today are islands, and why colonizers are so hesitant to relinquish control.

4.3 Forms of Government

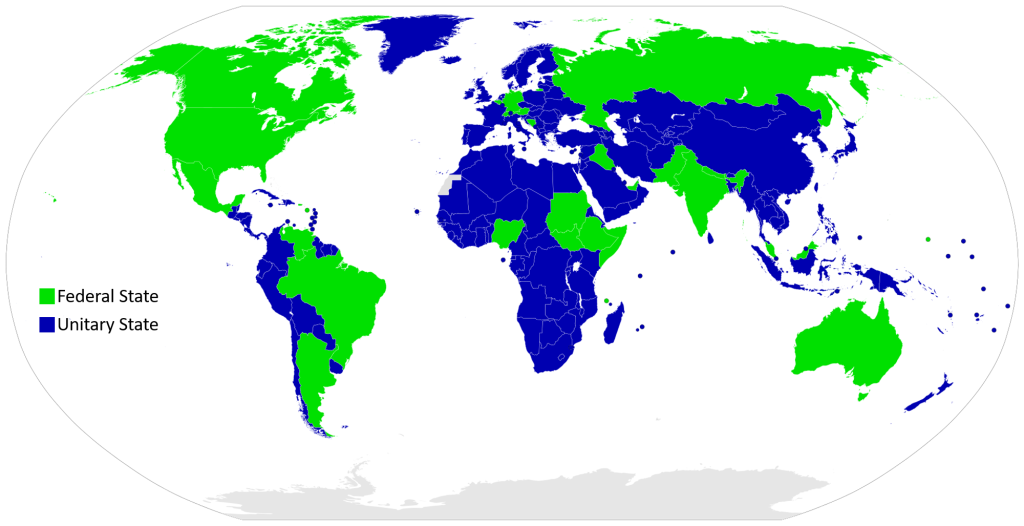

There are a variety of governmental systems found in the world today. We can first explore how the territories within a state are arranged and how much autonomy they might have. Broadly, we can divide the world into unitary states and federal states (see Figure 4.10). A unitary state system works best when you have a strong national unity, and they’re common in Europe and across Africa. Unitary states might have local administrative divisions, but they’re only given whatever power the central government decides to allocate them. In some cases, like Rwanda, Ghana, and Kenya, one ethnic group came to dominate the region, leading to a unitary state status.

Federal states, on the other hand, allocate power to units of local government within a country, such as territories, provinces, or states (referring to subnational entities). The United States is a federal state, which is common for large countries. Often, the capital is too far to adequately control the entire state. Most of the world’s largest states are federal, including Russia, Canada, Brazil, and India. Size isn’t the only factor, though. We must also take cultural and governmental factors into account. Belgium, for example, is federal, but quite small – why? The country is home to two fairly well-defined linguistic communities: the Dutch-speaking Flemish community and a French-speaking community known as Walloons. Thus, a federal structure allows each group to coexist with greater political autonomy. China, on the other hand, is a very large country but is unitary. Why is this the case? Their central government maintains a great deal of control. There been a strong global trend toward a federal government structure. France, for example, previously had a strong, unitary government. In recent years, the government has granted additional powers to regional and local governments. In Poland, there was a switch to the federal system with the collapse of communism.

In some states, a central government offers increased autonomy or delegates additional powers to a sub-national entity. This is known as devolution. Devolution is not the same thing as federalism, since these powers are granted by the central government and could be reversed or changed. Devolution can be a strategy to prevent a region within a country from declaring complete independence. In 2014, for example, Scotland narrowly voted to remain with the United Kingdom on an independence referendum, but the outcome of the vote led to some increased autonomy from the United Kingdom.

In addition to how the territories within a state are administered, we can also look at the various styles of government leadership found within countries. Some states are autocracies, where government rule is concentrated in the hands of one person. Other states are democracies, where people have the authority to choose their government leaders. While it might be tempting to simplify the various forms of government into the categories of “autocracies” or “democracies,” there are actually far more forms of government leadership. In an oligarchy, the power rests within a small group of people. Even within democratic governments, we find a wide variety of expressions from voters directly electing their leaders to the guise of elections but with pre-ordained outcomes determined by a few elite individuals.

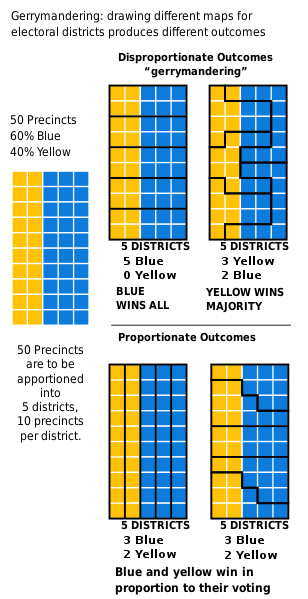

The internal boundaries of states can impact and reflect the balance of power within a country. Often, states are divided into different voting districts to elect local or state leaders. Electoral geography is a branch of political geography that specifically examines electoral politics. Of particular interest to electoral geographers is a practice known as gerrymandering. Gerrymandering is a tactic used to create voting districts in a way that benefits a particular political party. Essentially, as Figure 4.11 displays, if one party is in power and has the ability to draw electoral districts, they can draw them in a way that ensures they stay in power. Similarly, even with the same underlying population patterns, another party could draw districts in a way that ensures they maintain power.

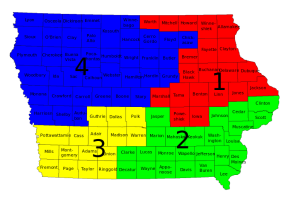

Within the United States, gerrymandering has been repeatedly used by both political parties to increase their power. Some states, like Iowa (see Figure 4.12), use a nonpartisan redistricting process that effectively eliminates gerrymandering. Their maps, by Iowa law, cannot take partisan factors into account when creating districts.

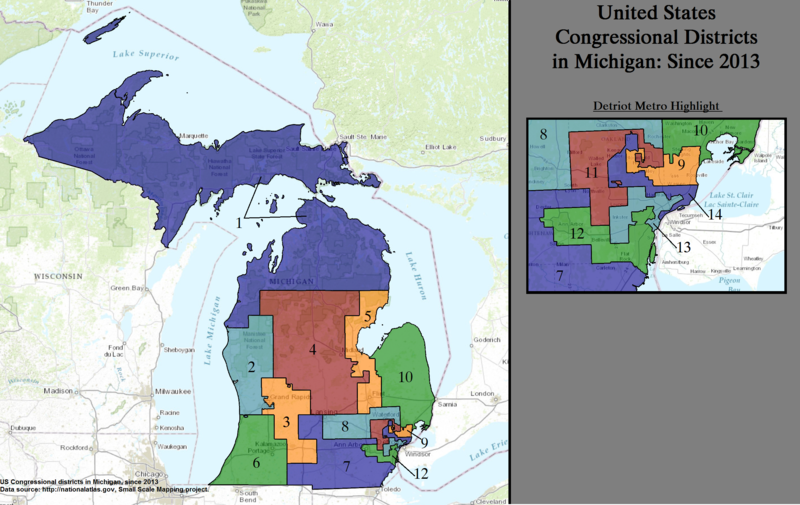

Other states, like Michigan, have utilized computer software to create gerrymandered districts that effectively keep one political party in power (see Figure 4.13). In the 2016 Congressional election in Michigan, for example, Republicans beat Democrats by only 1 percent in total votes – but won 9 of 14 seats. A grassroots campaign to end gerrymandering in Michigan was ultimately successful and an independent redistricting commission will redraw the state’s electoral districts in the future.

4.4 Political Challenges

Today’s states face a number of challenges, both international and domestic. As mentioned, a state might have struggles within its internal boundaries: perhaps a region wants more autonomy or a multi-ethnic state might struggle to create an acceptable balance of power for all parties. States might be in conflict with other states and this could lead to regional or global conflicts. Historically, balances of powers emerged between large empires and later states. The Soviet Union and the United States, for example, shared a balance of power for some time after World War II. To maintain this balance of power, both countries engaged in an arms race to ensure that neither country would have a military advantage. These countries still have a tense relationship.

But what of other groups who are not in this balance of power, and have relatively little global influence? Sometimes these groups turn to terrorist activity in order to meet their demands. Terrorism can be carried out by both individuals and organizations and broadly refers to the use of violence to achieve political goals. The terrorist attacks on 9/11 in the United States resulted in nearly 3,000 deaths. Al-Qaeda, a militant Islamist organization founded by Osama bin Laden, claimed responsibility for the attacks resulting in the U.S. declaring a “War on Terror.” The terrorist organization known as ISIS (the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria) then formed when the U.S. invaded Iraq. Members of ISIS are Sunni Muslims who were unemployed and felt marginalized as a result of political changes after the U.S. deposed Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein (who was also Sunni) and enabled the majority Shi’a to rule. While the U.S. has declared victory over ISIS, researchers caution that the recipe for the emergence of ISIS, such a lack of infrastructure and a feeling of political disenfranchisement, is still very much a concern in the region and could lead to the reemergence of ISIS or the creation of a new terrorist organization.

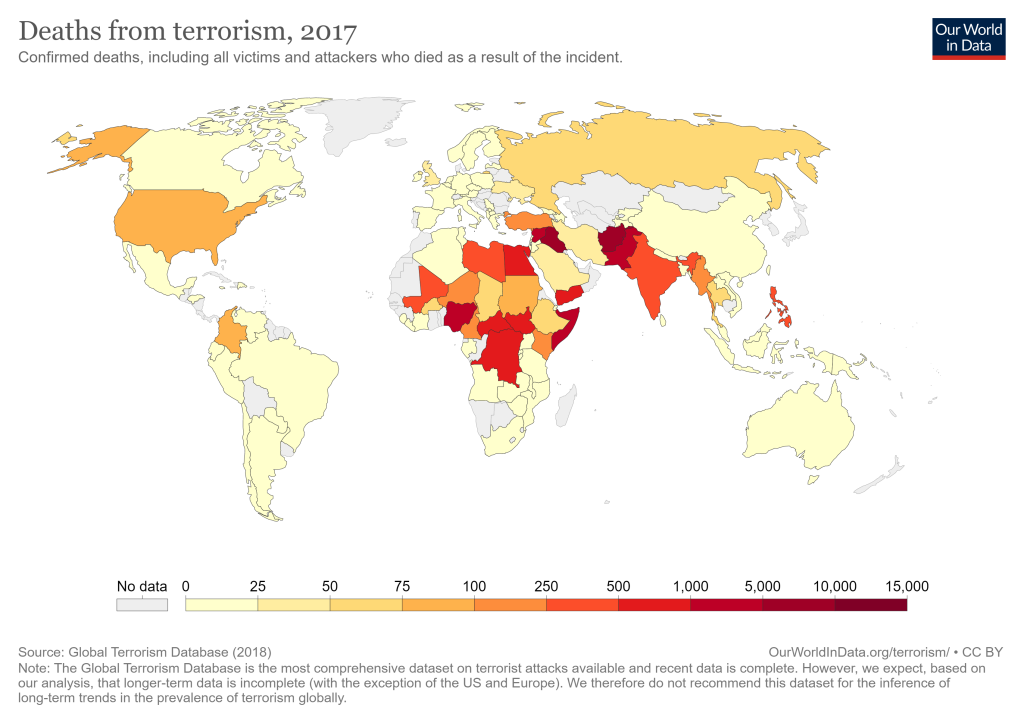

Terrorism isn’t just limited to threats from outside individuals and organizations, however. On April 19, 1995, Timothy McVeigh, an American domestic terrorist, bombed the federal building in Oklahoma City killing 168 people. He was motivated by the federal government’s handling of the Waco Siege in 1993 and the Ruby Ridge incident in 1992. His attack was timed to coincide with the second anniversary of the Waco Siege. Domestic terrorism has been on the rise in the United States for some time, fueled by social media and the Internet that has enabled radical ideas to be widely shared. In Ireland, “the Troubles,” referring to a 30-year conflict from the 1960s to 1998 between Unionists (primarily Protestants who wanted Northern Ireland to remain with the United Kingdom) and Irish nationalists (who were mostly Catholic and wanted Northern Ireland to leave the United Kingdom) led to the deaths of 3,500 people. Countries in North Africa and Southwest Asia have experienced the highest number of deaths from terrorism for the past decade (see Figure 4.14).

Why do we classify particular groups as terrorists or extremists? And how might this classification differ depending on our geographic location and background? Could a government be seen as engaging in terrorism? States might support terrorism, either covertly or overtly, through assisting terrorist activities against an adversary. This assistance might be in the form of monetary funding, providing supplies such as weapons, or offering sanctuary to individuals suspected as terrorism. Often, who we label as “terrorists” depends on how we interpret their actions. In addition, how we deal with the root causes of terrorism can significantly impact its reach and spread. Addressing underlying concerns (such as infrastructure needs, employment and education opportunities, and political representation) can help lessen the ability of terrorist groups and ideologies to gain new adherents.

Another political challenge states face is related to their own sovereignty. Sometimes this occurs as a result of armed conflicts or invasions by neighboring states. In other cases, though, a state might wish to trade some of its autonomy in order to create more regional cooperation. These political entities comprised of a number of different member states are known as supranational organizations, meaning that their organizational influence and control extends beyond the boundaries of a single state. Why would a state want to join such an organization and have less autonomy over their own decision-making? Sometimes, joining a regional or international organization can help states collectively develop and stabilize. ASEAN, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, was formed with the goal of accelerating economic growth and providing political and military integration among its member states and indeed the average economic growth of member states was considerably higher than non-member states during the decades after its founding. It can also be to a state’s advantage to join a supranational organization that will ensure that all states play by the same rules. Among other functions of the United Nations supranational organization is establishing collective global security and its Security Council can refer cases where rules have been violated, such as instances of war crimes or genocide, to the International Criminal Court.

The European Union (EU) was formed after World War II coalescing out of a number of regional organizations including Benelux, established in 1944 and comprised of the neighboring states of Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg, which sought greater political and economic cooperation between its member states, and the European Economic Community, which was created in 1957 and aimed to create a common market for its members. Today, the European Union has 27 member states, 19 of which use the euro, the official currency of the EU. The United Kingdom withdrew from the European Union in 2020, the only state to do so since its founding. (This withdrawal is commonly referred to as “Brexit,” a combination of the terms “Britain” and “exit.”) Those supporting the UK’s withdraw from the European Union argued that the the EU was a threat to the country’s sovereignty, since the UK was bound by trade agreements and immigration policies. Those wishing the UK to remain with the EU, on the other hand, believed the benefits of EU membership outweighed the costs and that being part of the EU made the UK economy stronger. Complicating this vote is that the United Kingdom, as mentioned, is a multi-ethnic state, and certain nations within the UK opposed the state leaving the EU. The majority of voters in Scotland and Northern Ireland voted to remain with the European Union.

As supranational organizations have grown, both in the number of member states and in their global reach and scope, citizens in member countries will likely continue to grapple with weighing the benefits of joining and remaining a part of these groups against areas where they believe their national autonomy is being compromised. Similarly, as states exert their global influence and seek their own economic development, this may lead to conflict when other states and/or ethnic groups feel their own rights have been infringed.

4.5 Maintaining Unity

With all of the many changes and challenges facing our world, how can a state possibly maintain unity? Centripetal forces are those that serve to unify a state and bring people together. Can you think of any examples of centripetal forces? In the United States, examples of these might be the Pledge of Allegiance which is recited in schools across the country each day. When a country is attacked by an outside foe, citizens often come together to defeat a common enemy, another example of a centripetal force. National symbols, national anthems, state holidays celebrating a country’s heritage, all could be ways to unify people within a country. Shared cultural features can also bring people together within a country, such as sharing a common language or ethnic identity. Centripetal forces are sometimes equated with nationalism.

On the other hand, centrifugal forces are those that push people apart. (Think of a centrifuge, as in biology or chemistry.) If centripetal forces include things like shared cultural features, what would centrifugal forces be? Ethnic differences may serve as centrifugal forces, particularly if one ethnicity sees themselves as superior or has most of the political power. Sometimes, centrifugal forces can be geographic, such as a formidable physical barrier such as a mountain range or a distant, poorly-connected piece of territory. If centrifugal forces cannot be overcome, a state may break up into a smaller independent units, which may be hostile toward one another, a process known as balkanization, named after the Balkan peninsula region of Europe. Yugoslavia was a former state that came into existence after World War I and was comprised of a number of distinct ethnic and religious groups. The dictator Josip Broz Tito led the country for some time and attempted to unify it, but ethnic tensions grew after his death in 1980 and a series of violent ethnic conflicts erupted, leading to the deaths of over 100,000 people and displacing far more. By the early 1990s, republics within Yugoslavia began declaring their independence. Today, seven states comprise former Yugoslavia (see Figure 4.15), including the newest state, Kosovo, which declared independence from Serbia in 2008.

One danger of establishing and maintaining political unity is that if cultural features are used as centripetal forces, this can be difficult to maintain as the cultural landscape changes. If the ideal citizen is seen as someone who looks or speaks or believes a certain way, what happens when there are minority groups who may not share that identity, or when migrants settle in an area? Nationalism, when taken to the extreme, is known as fascism, where a dictator rules and espouses a form of ultranationalism. As the world has become more interconnected and globalized, certain groups within states may feel like their state’s cultural identity is changing, and their individual roles in society may be changing, so movements promoting ultranationalism may be appealing, though this can ultimately serve to threaten national unity and may lead to conflict.

Maintaining political unity may be a balance, then, between crafting a state identity that doesn’t exclude certain groups but at the same time, finding enough ideals that citizens hold in common to develop a shared sense of national pride and belonging. While some may view the current landscape of the United States as highly divisive, Americans in fact agree on a great deal, as a 2020 survey conducted for Harvard University’s Carr Center for Human Rights and Institute of Politics illustrates. In that survey, over two-thirds of respondents agreed with the statement: “Americans have more in common with each other than many people think” and over 90% of respondents in each category of political affiliation (Democrat, Republican, and Independent) agreed that Americans have an essential right to clean air and water, a quality education, and the protection of personal data. It can be more difficult to promote unity around these kinds of ideals compared to establishing a national religion or a national language, but then again, these values may be able to better withstand the test of time.

an organized territory led by a government that has control over its domestic and foreign interests

the authority of a state to govern itself within a territory

a sovereign city that controls the surrounding territory

a territory that is ruled by another state

a region caught between more powerful states (can also be spelled shatterbelt)

an independent state that has a homogenous cultural and ethnic identity

a group of people with a strong cultural and ethnic identity

an ethnic group that does not govern its own state and is not the majority population of any nation-state

the right of a group of people to govern themselves

a form of control using economic influence or indirect political control rather than direct military or political authority

a boundary that was created before modern human settlement occurred

a boundary established after human settlement

a boundary created by an outside power that ignores underlying cultural differences

a boundary that no longer functions but is still apparent on the landscape

a shape of a state where the distance from the center to any point on the boundary is roughly the same

a state that is long and narrow

a shape of a state that has an extension that protrudes from its main territory

see prorupted state

a state that is fragmented into multiple, noncontiguous parts

a state that completely surrounds another state

a boundary within a state

a form of government where a central government entity has all or most of the governing power

a form of government where the power resides in units of local government, such as self-governing territories or states.

when a central government delegates additional powers to a sub-national entity

a form of government where power is held by a single ruler

a form of government where people have the right to select their leaders

a form of government where the power structure rests with a small group of people

a political tactic used to create voting districts that give an advantage to one political party

the use of violence to achieve political goals

an organization or political entity that is comprised of a number of different member states and whose administrative structure extends across multiple national boundaries

a force that unifies people within a state

a force that pushes people apart within a country and threatens national unity

the process of a state breaking up into a smaller independent units, which may be hostile toward one another

a political system characterized by an extreme form of nationalism and the rule by a dictator