4.2 Political Identities

Separatist Movements

Occasionally people within a country find themselves unable to agree on the rules under which they can all live peaceably. When this happens, a separatist movement is likely to ensue. Often separatist movements revolve around questions of control over religious practice, language, or other cultural questions. Usually, it is a minority group, often living in a peripheral region of the country that is the offended party ready to break away from the majority group living in the country’s hearth or core region.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3V2JO24e9P8

Thousands of separatist movements have marked world history, and hundreds of separatist groups are active today. Even within prosperous Europe, dozens of ethnic groups (nations) would like to break away to establish their nation-state in Europe alone. In principle, Americans and American foreign policy support the right to self-determination, which is essentially the right of a group of people to control the political system of the territory in which they live. Indeed, the United States itself was born of a rebellion by separatists living in a marginalized, peripheral region of the British Empire. American colonists’ rallying cry for self-determination was “no taxation without representation.” For many years, Scotland has debated its inclusion in the United Kingdom (England, Wales, Northern Ireland, and Scotland).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ma9KNLy_4dw

Scottish people, many of whom are resentful of the dominance of their more numerous English neighbors, held a parliamentary vote in late 2014 to decide the question, “Should Scotland be an independent country?” Ultimately, the Scots voted to stay part of the United Kingdom but to keep Scotland in the United Kingdom; the English gave into several demands by Scottish separatists for additional autonomy from the British (English) control. Fast forward to June 2016 when the U.K. shocked the world by voting to leave the European Union; Scottish separatists took advantage of the political and social instability to renew their call for independence and self-determination.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YSfmmsI_Xyw

Politics and Identity

Separatist movements do not always arise from perceived differences in identity. Just as often, the real difference is economical, but those who would lead a group to rebel rarely admit this basic fact. The American Civil War was less a fight over identity as it was over the control over rules governing slavery and the economics of slavery. Both sides of the conflict identified as American, but Southerners believed control should be local, and most Northerners believed that some of that local control regarding slavery, should be a matter of national control.

Perhaps the most interesting thing about civil wars and separatist movements is that often those who suffer the most gain the least when fighting breaks out. As was the case in the American Civil War, the vast majority of soldiers from the South owned no slaves, and stood to gain from wage competition in the labor market upon emancipation. It was the elite Southerners that needed slavery. So how is it that people without much to fight for can be convinced to fight?

Some of the answers lie in the ability of people in power to manipulate the opinions of segments of a population effectively. Populist politicians often convince people that their individual or their groups’ problems are the results of unfair treatment by another group. Sometimes, these arguments are legitimate and can be supported by fact; other times, there is insufficient evidence to justify rebellion or secession.

It is often nearly impossible to determine precisely whose interests a secessionist group represents. Sometimes, secession movements are led by a small political elite that claims the right to represent a more substantial majority. However, the elite may not be representative of the majority of the people, and their motives may be strictly personal (wealth, power). This is why the United States’ foreign policy finds questions of self-determination, especially perplexing. Our government has yet to find a consistent response to those groups who desire to control their territory. In some cases, the U.S. has supported the rights of subnational groups to create a new country. The Clinton administration largely supported the dissolution of Yugoslavia into multiple new countries.

In other instances, the U.S. has worked with groups trying to exercise that right. Take, for example, the Kurdish people, an ethnic minority in northern Iraq, eastern Turkey and northwestern Iran. The Kurds have a separate language, history and identity from the Iraqis, Iranians and the Turks with whom they share space. Many Kurdish nationalists argue that there should be a new nation-state called Kurdistan. It would seem the Kurds have a legitimate argument, and there have been several Kurdish insurrections over the years. Each time though, Kurdish rebellions have been met with violence by the governments of Turkey, Iraq, and Iran. The U.S. government supported some measures of Kurdish autonomy in Iraq and Iran, but not in Turkey, presumably because that country is a strategic ally of the U.S.

Terrorism

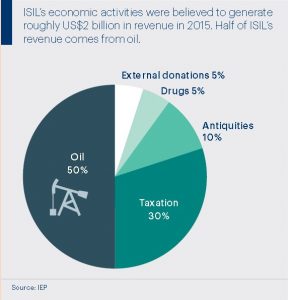

Terrorism is proving to be an enduring global threat, because modern terrorist groups have become more lethal, networked, and technologically savvy. Today, groups such as the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) and al-Qa’ida can control land and hold entire cities hostage. This power mainly stems from their ability to generate revenue from numerous criminal activities with almost complete impunity.

During the time of the 11 September 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, al-Qa’ida numbered around 300 mujahedeen in Afghanistan with the support of the Taliban. Fifteen years later, two global terrorist groups have emerged, transforming the global threat landscape – al-Qa’ida and ISIS. At the end of 2015, ISIS controlled 6-8 million people in an area the size of Belgium, and maintained a force of between 30,000- 50,000 fighters while attracting the most significant number of foreign fighters in history.

Currently, al-Qa’ida and ISIS are escalating their attacks in an intense rivalry for global prowess and international reach while competing for affiliates worldwide. With its determination to govern and control territories in the Middle East, Africa, and Asia, ISIS is currently a more significant threat than al-Qa’ida. It represents a three- dimensional threat: a core situated in Iraq and Syria, ISIS regional affiliates, and ISIS online. This constellation has spawned ISIS-inspired foreign fighters, ISIS self-inspired radicalized cells, ISIS affiliates, and, most importantly, ISIS criminal financing operations. As will be shown, ISIS criminal networks and operations are supported by all three dimensions.

Since ISIS declared its caliphate in June 2014, ISIS core, regional affiliates, and inspired groups have carried out more than 4,000 attacks in 28 countries. ISIS’s geographic presence has grown exponentially since it hit the world stage in 2014. ISIS has a total of 30 self- proclaimed wilayats or provinces, ten of which are outside of ISIS’s core base in Syria and Iraq. These include regional affiliates in Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia and Yemen, as well as allied affiliates in Afghanistan and Pakistan. ISIS in Afghanistan consists of former members of the Afghan Taliban, the Haqqani Network, and the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) and it is supported by Jamaat Ul Dawa al Quran (JDQ). These groups have generated millions annually from narcotics trafficking and illegal extraction of precious stones and timber. As former members continue to splinter off, ISIS is thus not only generating an income from its wiliyats, but also through criminal markets of other groups. ISIS is actively making links to Southeast Asian terror groups as well. Home to 62 percent of the world’s Muslims, the Asia Pacific region offers ISIS not only a new base to establish power, but also new avenues of revenue to exploit.

Al-Qa’ida similarly operates on a franchise model, with offshoots in Africa and Asia, and it is developing new relationships with groups in the Caucasus, India, and Tunisia. Al-Qa’ida is also working towards territorial control, and in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) continues to have a strong presence in Yemen and remains the group’s greatest direct threat to the United States.

The opportunistic ability for criminal-terrorist groups to take over geographic areas is due to collapsing state power and conflict in the Middle East and North Africa. The instability brought on after the wake of the Arab Spring, which led to hundreds of thousands of people trying to escape to Europe, further undermined state control challenging the authoritarian order in six Arab states. Four states — Libya, Iraq, Syria, and Yemen – are failing or partially failing, leading to chronic conflict, lawlessness, and extreme poverty in the region. This has created an opportunity for radical religious extremists, terrorists, and criminal groups to prosper. Several states in the region can now no longer entirely control and contain criminality and violent terror within their borders.

States worldwide are being challenged by criminal-terrorist networks, especially in prisons, urban areas, and cyberspace. Prisons have become a place where terrorists and criminals meet, plan, plot, and recruit. The most prominent example was Abu-Bakhr al- Baghdadi, the leader, and self- declared caliph of ISIS, who spent formative time at Camp Bucca, a US-controlled prison in Iraq, where he met Samir Abd Muhammad al-Khlifawi, a former colonel in the intelligence service of Saddam Hussein’s air defense forces, who was the architect of the ISIS strategy for the takeover of towns, focusing heavily on surveillance and espionage. The Iraqi government estimates that 17 of the 25 most crucial ISIS leaders spent time in U.S. prisons in Iraq, planning the creation of ISIS and its ideology.

In the West, prisons have also become a networking and learning environment where terrorists and criminals can share an ideology and build networks. A large percentage of terrorist recruits, some estimates are as high as 80 percent, have criminal records varying from petty to serious crimes. The recruitment of criminals provides terrorists with the skill sets needed to succeed: a propensity to carry out violent acts, the ability to act discreetly, and access to criminal markets for weapons, and bomb-building resources. A study on extremists who plotted attacks in Western Europe found that 90 percent of the cells were involved in income-generating criminal activities, and a half was entirely self-financed: only one in four received funding from international terrorist organizations.

For Islamist extremist groups, the prison has become a vital recruitment location. They especially target young petty criminals with Middle Eastern backgrounds. The Charlie Hebdo attackers Amedy Coulibaly and Cherif Kouachi, for example, met in prison. There, they also met al-Qa’ida’s top operative in France, Djamel Beghal, who served time for attempting to bomb the U.S. Embassy in Paris in 2001. Abdelhamid Abaaoud, the mastermind of the Paris plot, as well as his co-conspirator Salah Abdeslam, also followed a trajectory from petty crime to armed robbery, both ending up in prison, where they met and were radicalized by Fouad Belkacem, the former leader of the Brussels terrorist recruiting organization Sharia4Belgium.

State power is also progressively being weakened in large cities and ports. Urban centers harbor lawless enclaves that are exploited by criminals, terrorists, militants, and bandits. In so-called feral cities, such as Mogadishu, Caracas, Ciudad Juárez, and Raqqa, governments have lost their ability to govern or maintain the rule of law. To build up more resilience in cities, the U.N. launched the Strong Cities Network (SCN) in September 2015.

While terrorists have created insecurity in the real world for decades, there has been a significant paradigm shift for the last 15 years: terrorists are now engaged in the world’s greatest open space, the internet. ISIS’s growing global influence marks the first time in history that a terrorist group has held sway in both the real and virtual worlds. Cyberspace has become a new domain for violence. It is used to project force with videos of torture and assassinations as well as to recruit.

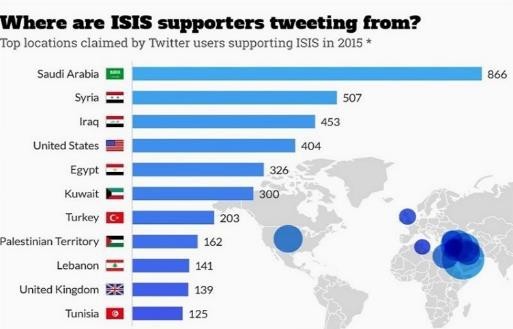

In cyberspace, extremist groups’ greatest success is their ability to use propaganda in a strategic way to entice fighters and followers. ISIS uses the digital world to create an idealized version of itself, a reality show that is designed to find resonance and meaning among its diverse supporters. For the adventure seeker, it broadcasts its military power and violence; for those looking for a home, job, refuge, religious fulfillment, or meaning in life, it uses this medium to present an idyllic world by depicting the caliphate as a peaceful, benevolent state committed to helping the poor. ISIS maintains a successful media wing, Al-Furqan, which includes over 36 separate media offices. Together, they produce hundreds of videos, as well as Roumiay (formerly Dabiq), ISIS’s online propaganda magazine. A study by RAND found that ISIS supporters sent over six million tweets from July 2014-May, 2015.

More than 40,000 foreign fighters from over 120 countries have flooded into Syria since the start of the country’s civil war, including 6,900 from the West, the vast majority of whom joined ISIS. The group is dependent on recruits from Europe for significant funding. It advises aspiring fighters to raise funds before leaving to join ISIS. European recruits’ moneymaking schemes include petty theft, as well as defrauding public institutions and service providers. British foreign fighters committed large-scale fraud by pretending to be police officers and targeting U.K. pensioners for their bank details, earning more than US$1.8 million before being apprehended.

ISIS has also been successful at using cybercrime to fund itself. It advises fighters on how to transfer funds through money service businesses, pre-paid debit cards, Apple Wallet, informal money transfer systems (hawala), and Dark Wallet, a dark web app that claims to anonymize bitcoin transactions. ISIS also instructs its followers to use the internet to acquire weapons. Cells planning attacks in Europe and ‘lone wolves’ are increasingly turning to the dark web to obtain weapons: 57 people were arrested in France in 2015 for buying firearms over the internet.

The recent increase in global terrorism can be explained by several factors that have converged: war, religious and ethnic conflict, corrosive governments, weak militaries, failing states, and the growth of information technology. However, one of the most important developments is the increasing collaboration between criminal and terrorist networks. While political motives drove criminals used to focus only on revenue generation and terrorists, we are currently witnessing a convergence of terrorism and crime. These new hybrid groups are driven by both, revenue generation and political motives, resulting in criminal and terrorist groups with historically unprecedented resources and transgressive aims. The consequence of this expanding threat can be measured by how terrorist groups have increased their sphere of influence worldwide. Below are other examples of terrororism that is occuring around the world.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p6De3TwoOFo

Geospatial Intelligence

Geospatial technology is used heavily in geopolitical conflicts within the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, National Security Agency, and the Department of Homeland Security, and the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to name a few. The video on the right is a section of the Geospatial Revolution, Episode 3 that focuses on war and conflict.

Click here to read an interesting article from WIRED Magazine titled How Geospatial Analytics is Helping Hunt the LRA and al-Shabaab.

Geospatial technology can also be used for humanitarian efforts as a way to end conflict or monitor situations before they escalate. One organization, called the Satellite Sentinal Project, was created by The Enough Project and the largest private satellite imagery corporation called Maxar (formally called Digital Globe). The organization was first used satellite imagery from satellite imagery and Google Earth to monitor potential humanitarian conflicts along the border of Sudan and the newly created South Sudan. Now it is using satellite imagery to track poachers who use the money from the black market to fund civil wars like the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA).