7 Political Economy and International Trade

Some Features of a Democratic Society

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aTbtKRdYbYo

Learning Objective

1. Understand how and why lobbying is used to influence the policy decisions of a government.

A government represents the interests of its citizens. As Abraham Lincoln said in the Gettysburg Address, a democratic government is meant to be by the people and for the people. Thus, in a representative democracy, government officials are entrusted to take actions that are in the interests of their constituents. Periodic elections allow citizens to vote for individuals they believe will best fulfill their interests. If elected officials do not fulfill the interests of their constituents, then those constituents eventually have a chance to vote for someone else. Thus, if elected officials are perceived as good representatives of their constituents’ interests, they are likely to be reelected. If they follow their own individual agenda, and if that agenda does not match the general interests of their constituents, then they may lose a subsequent bid for reelection.

Citizens in democratic societies are traditionally granted the right to free speech. It is generally accepted that people should be allowed to voice their opinions about anything in front of others. In particular, people should be free to voice their opinions about government policies and actions without fear of reprisal. Criticisms of, as well as recommendations for, government policy actions must be allowed if a truly representative government is to operate effectively.

The Nature of Lobbying

We can define lobbying as the activity wherein individual citizens voice their opinions to the government officials about government policy actions. It is essentially an information transmission process. By writing letters and speaking with officials, individuals inform the government about their preferences for various policy options under consideration. We can distinguish two types of lobbying: casual lobbying and professional lobbying.

Casual lobbying occurs when a person uses his leisure time to petition or inform government officials of his point of view. Examples of casual lobbying are when people express their opinions at a town meeting or when they write letters to their Congress members. In these cases, there is no opportunity cost for the economy in terms of lost output, although there is a cost to the individual because of the loss of leisure time. Casual lobbying, then, poses few economic costs except to the individual engaging in the activity.

Professional lobbying occurs when an individual or company is hired by someone to advocate a point of view before the government. An example is a law firm hired by the steel industry to

help win an antidumping petition. In this case, the law firm will present arguments to government officials to try to affect a policy outcome. The law firm’s fee will come from the extra revenue expected by the steel industry if it wins the petition. Since, in this case, the law firm is paid to provide lobbying services, there is an opportunity cost represented by the output that could have been produced had the lawyers engaged in an alternative productive activity. When lawyers spend time lobbying, they can’t spend time writing software programs, designing buildings, building refrigerators, and so on. (This poses the question, what would lawyers do if they weren’t lawyering?) The lawyers’ actions with this type of lobbying are essentially redistributive in nature, since the lawyers’ incomes will derive from the losses that will accrue to others in the event that the lobbying effort is successful. If the lobbying effort is not successful, the lawyers will still be paid, only this time the losses will accrue to the firm that hired the lawyers. For this reason, lobbying is often called rent seeking because the fees paid to the lobbyists come from a pool of funds (rents) that arise when the lobbying activity is successful. Another name given to professional lobbying in the economics literature is a directly unproductive profit-seeking (DUP) activity .

Lobbying is necessary for the democratic system to work. Somehow information about preferences and desires must be transmitted from citizens to the government officials who make policy decisions. Since everyone is free to petition the government, lobbying is the way in which government officials can learn about the desires of their constituents. Those who care most about an issue will be more likely to voice their opinions. The extent of the lobbying efforts may also inform the government about the intensity of the preferences as well.

Key Takeaways

• In a representative democracy, citizens have the right to both elect their representatives and discuss policy options with their elected representatives.

• Lobbying is the process of providing information to elected officials to influence the policies that are implemented.

• A directly unproductive profit-seeking (DUP) activity is any action that by itself does not directly produce final goods and services consumed by a country’s consumers.

The Economic Effects of Protection: An Example

Learning Objective

1. Depict numerical values for the welfare effects of a tariff by a small country.

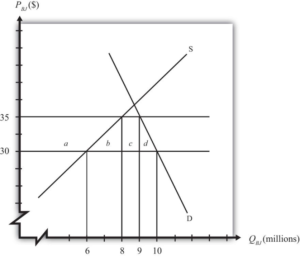

Consider the market for blue jeans in a small importing country, depicted in Figure 10.1 "A Market for Blue Jeans". Suppose a sudden increase in the world supply of jeans causes the world market price to fall from $35 to $30. The price decrease causes an increase in domestic demand from nine to ten million pairs of jeans, a decrease in domestic supply from eight to six million pairs, and an increase in imports from one to four million.

Figure 10.1 A Market for Blue Jeans

Because of these market changes, suppose that the import-competing industry uses its trade union to organize a petition to the government for temporary protection. Let’s imagine that the industry calls for a $5 tariff so as to reverse the effects of the import surge. Note that this type of action is allowable to World Trade Organization (WTO) member countries under the “escape clause” or “safeguards clause.”

We can use the measures of producer surplus and consumer surplus to calculate the effects of a $5 tariff. These effects are summarized in Table 10.1 "Welfare Effects of an Import Tariff". The dollar values are calculated from the respective areas on the graph in Figure 10.1 "A Market for Blue Jeans".

Table 10.1 Welfare Effects of an Import Tariff

Area on Graph $ Value

Consumer Surplus − (a + b + c + d) − $47.5 million

Producer Surplus + a + $35 million

Govt. Revenue + c + $5 million

National Welfare − (b + d) − $7.5 million

Notice that consumers lose more than the gains that accrue to the domestic producers and the government combined. This is why national welfare is shown to decrease by $7.5 million.

In order to assess the political ramifications of this potential policy, we will make some additional assumptions. In most markets, the number of individuals that makes up the demand side of the market is much larger than the number of firms that makes up the domestic import-competing industry. Suppose, then, that the consumers in this market are made up of millions of individual households, each of which purchases, at most, one pair of jeans. Suppose the domestic blue jeans industry is made up of thirty-five separate firms.

Key Takeaway

• With quantities, prices, and the tariff rate specified, actual values for the changes in consumer and producer surplus and government revenue can be determined.