Emily P. Harris

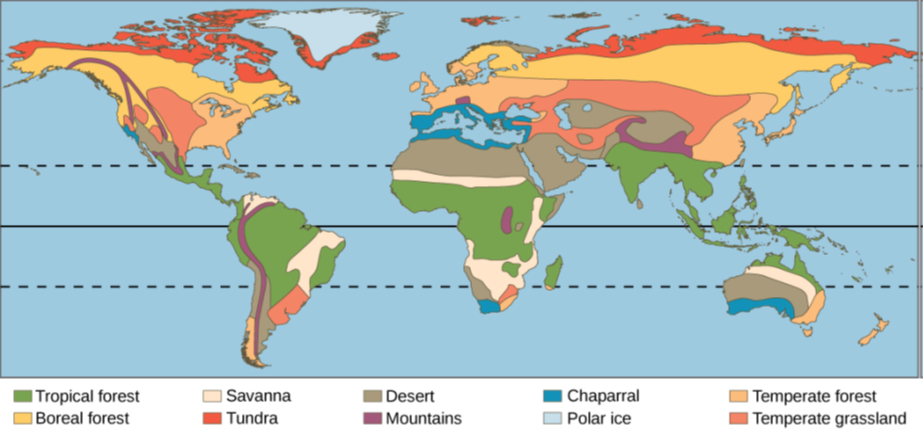

There are eight major terrestrial biomes: tropical rainforests, savannas, subtropical deserts, chaparral, temperate grasslands, temperate forests, boreal forests, and Arctic tundra. Biomes are large-scale environments distinguished by characteristic temperature ranges and precipitation amounts. These two variables affect the vegetation and animal life types in those areas. Because each biome is defined by climate, the same biome can occur in geographically distinct areas with similar climates (Figures 1 and 2).

Tropical rainforests are found in equatorial regions (Figure 1) are the most biodiverse terrestrial biome. This biodiversity is under extraordinary threat, primarily through logging and deforestation for agriculture. Tropical rainforests have also been described as nature’s pharmacy because of the potential for new drugs largely hidden in the chemicals produced by the huge diversity of plants, animals, and other organisms. The vegetation is characterized by plants with spreading roots and broad leaves that fall off throughout the year, unlike the trees of deciduous forests that lose their leaves in one season.

The temperature and sunlight profiles of tropical rainforests are stable compared to other terrestrial biomes, with average temperatures ranging from 20oC to 34oC (68oF to 93oF). Unlike forests farther from the equator, tropical rainforests’ monthly temperatures are relatively constant. This lack of temperature seasonality leads to year-round plant growth rather than just seasonal growth. In contrast to other ecosystems, a consistent daily amount of sunlight (11–12 hours per day year-round) provides more solar radiation and, therefore, more opportunity for primary productivity.

The annual rainfall in tropical rainforests ranges from 125 to 660 cm (50–200 in) with considerable seasonal variation. Tropical rainforests have wet months in which there can be more than 30 cm (11–12 in) of precipitation and dry months in which there is less than 10 cm (3.5 in) of rainfall. However, the driest month of a tropical rainforest can still exceed the annual rainfall of some other biomes, such as deserts. Tropical rainforests have high net primary productivity because the annual temperatures and precipitation values support rapid plant growth. However, the high amounts of rainfall leach nutrients from the soils of these forests.

Tropical rainforests are characterized by vertical vegetation layering and distinct animal habitats within each layer. A sparse layer of plants and decaying plant matter is on the forest floor. Above that is an understory of short, shrubby foliage. A layer of trees rises above this understory and is topped by a closed upper canopy—the uppermost overhead layer of branches and leaves. Some additional trees emerge through this closed upper canopy. These layers provide diverse and complex habitats for various plants, animals, and other organisms. Many species of animals use the variety of plants and the complex structure of tropical wet forests for food and shelter. Some organisms live several meters above ground, rarely descending to the forest floor.

Savannas are grasslands with scattered trees in Africa, South America, and northern Australia (Figure 4). Savannas are hot, tropical areas with temperatures averaging 24oC –29oC (75oF –84oF) and an annual rainfall of 51–127 cm (20–50 in). Savannas have an extensive dry season and consequent fires. As a result, relatively few trees are scattered in the grasses and forbs (herbaceous flowering plants) that dominate the savanna. Because fire is an important source of disturbance in this biome, plants have evolved well-developed root systems that allow them to quickly re-sprout after a fire.

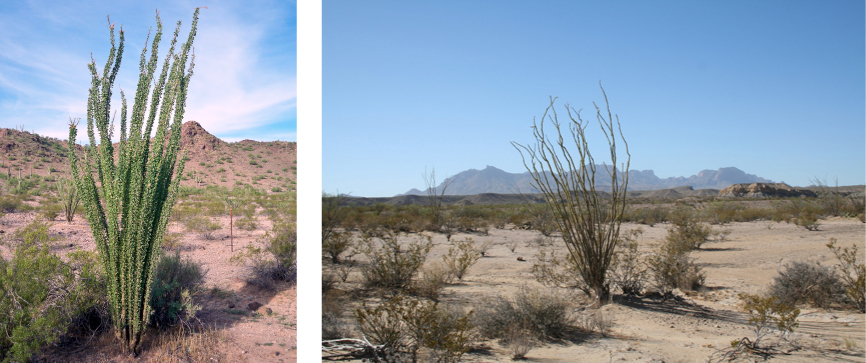

Subtropical deserts exist between 15o and 30o north and south latitude and are centered on the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn (Figure 6 below). Deserts are frequently located on the downwind or lee side of mountain ranges, which create a rain shadow after prevailing winds drop their water content on the mountains. This is typical of the North American deserts, such as the Mohave and Sonoran deserts. Deserts in other regions, such as the Sahara Desert in northern Africa or the Namib Desert in southwestern Africa, are dry because of the high-pressure, dry air descending at those latitudes. Subtropical deserts are very dry; evaporation typically exceeds precipitation. Subtropical hot deserts can have daytime soil surface temperatures above 60oC (140oF) and nighttime temperatures approaching 0oC (32oF). Subtropical deserts are characterized by low annual precipitation of fewer than 30 cm (12 in) with little monthly variation and a lack of predictability in rainfall. Some years may receive tiny amounts of rainfall, while others receive more. In some cases, the annual rainfall can be as low as 2 cm (0.8 in) in subtropical deserts located in central Australia (“the Outback”) and northern Africa.

The low species diversity of this biome is closely related to its low and unpredictable precipitation. Despite the relatively low diversity, desert species exhibit fascinating adaptations to the harshness of their environment. Very dry deserts lack perennial vegetation that lives from one year to the next; instead, many plants are annuals that grow quickly and reproduce when rainfall does occur, then die. Perennial plants in deserts are characterized by adaptations that conserve water: deep roots, reduced foliage, and water-storing stems (Figure 6). Seed plants in the desert produce seeds that can lie dormant for extended periods between rains. Most animal life in subtropical deserts has adapted to a nocturnal life, spending the hot daytime hours beneath the ground. The Namib Desert is the oldest on the planet and has probably been dry for more than 55 million years. It supports a number of endemic species (species found only there) because of this great age. For example, the unusual gymnosperm Welwitschia mirabilis is the only extant species of an entire order of plants. There are also five species of reptiles considered endemic to the Namib.

In addition to subtropical deserts, some cold deserts experience freezing temperatures during the winter, and any precipitation is in the form of snowfall. The largest of these deserts are the Gobi Desert in northern China and southern Mongolia, the Taklimakan Desert in western China, the Turkestan Desert, and the Great Basin Desert of the United States.

The chaparral is also called scrub forest and is found in California, along the Mediterranean Sea, and along the southern coast of Australia (Figure 7). The annual rainfall in this biome ranges from 65 cm to 75 cm (25.6–29.5 in), and most of the rain falls in the winter. Summers are very dry, and many chaparral plants are dormant during the summertime. The chaparral vegetation is dominated by shrubs and is adapted to periodic fires, with some plants producing seeds that germinate only after a hot fire. The ashes left after a fire are rich in nutrients like nitrogen and fertilize the soil, promoting plant regrowth. Fire is a natural part of the maintenance of this biome.

Temperate grasslands are found throughout central North America, also known as prairies, and in Eurasia, where they are known as steppes (Figure 8 below). Temperate grasslands have pronounced annual fluctuations in temperature, with hot summers and cold winters. The annual temperature variation produces specific growing seasons for plants. Plant growth is possible when temperatures are warm enough to sustain plant growth, which occurs in the spring, summer, and fall.

Annual precipitation ranges from 25.4 cm to 88.9 cm (10–35 in). Temperate grasslands have few trees except those found growing along rivers or streams. The dominant vegetation tends to consist of grasses. Low precipitation, frequent fires, and grazing maintain the treeless condition. The vegetation is very dense, and the soils are fertile because the soil subsurface is packed with these grasses’ roots and rhizomes (underground stems). The roots and rhizomes anchor plants into the ground and replenish the soil’s organic material (humus) when they die and decay.

Fires, a natural disturbance in temperate grasslands, can be ignited by lightning strikes. It also appears that the lightning-caused fire regime in North American grasslands was enhanced by intentional burning by humans. When a fire is suppressed in temperate grasslands, the vegetation becomes scrub and dense forests. Often, the restoration or management of temperate grasslands requires controlled burns to suppress the growth of trees and maintain the grasses.

Temperate forests are the most common biome in eastern North America, Western Europe, Eastern Asia, Chile, and New Zealand (Figure 9 below). This biome is found throughout mid-latitude regions. Temperatures range between –30oC and 30oC (–22oF to 86oF) and drop below freezing annually. These temperatures mean that temperate forests have defined growing seasons during the spring, summer, and early fall. Precipitation is relatively constant throughout the year and ranges between 75 cm and 150 cm (29.5–59 in).

Deciduous trees are the dominant plant in this biome, with fewer evergreen conifers. Deciduous trees lose their leaves each fall and remain leafless in the winter. Thus, little photosynthesis occurs during the dormant winter period. Each spring, new leaves appear as temperature increases. Because of the dormant period, the net primary productivity of temperate forests is less than that of tropical rainforests. In addition, temperate forests show far less diversity of tree species than tropical rainforest biomes.

The trees of the temperate forests leaf out and shade much of the ground. However, more sunlight reaches the ground in this biome than in tropical rainforests because trees in temperate forests do not grow as tall as trees in tropical rainforests. The soils of the temperate forests are rich in inorganic and organic nutrients compared to tropical rainforests. This is because of the thick layer of leaf litter on forest floors and rainfall’s reduced leaching of nutrients. As this leaf litter decays, nutrients are returned to the soil. The leaf litter also protects soil from erosion, insulates the ground, and provides habitats for invertebrates and predators.

The boreal forest, also known as taiga or coniferous forest, is roughly between 50o and 60o north latitude across most of Canada, Alaska, Russia, and northern Europe (Figure 10 below). Boreal forests are also found above a certain elevation (and below high elevations where trees cannot grow) in mountain ranges throughout the Northern Hemisphere. This biome has cold, dry winters and short, cool, wet summers. The annual precipitation is from 40 cm to 100 cm (15.7–39 in) and usually forms snow; relatively little evaporation occurs because of the cool temperatures.

The long and cold winters in the boreal forest have led to the predominance of cold-tolerant cone-bearing plants. These are evergreen coniferous trees like pines, spruce, and fir that retain their needle-shaped leaves year-round. Evergreen trees can photosynthesize earlier in the spring than deciduous trees because less energy from the Sun is required to warm a needle-like leaf than a broad leaf. Evergreen trees grow faster than deciduous trees in the boreal forest. In addition, soils in boreal forest regions tend to be acidic, with little available nitrogen. Leaves are a nitrogen-rich structure, and deciduous trees must produce a new set of these nitrogen-rich structures each year. Therefore, coniferous trees that retain nitrogen-rich needles in a nitrogen-limiting environment may have had a competitive advantage over the broad-leafed deciduous trees.

The net primary productivity of boreal forests is lower than that of temperate forests and tropical wet forests. The aboveground biomass of boreal forests is high because these slow-growing tree species are long-lived and accumulate standing biomass over time. Species diversity is less than that seen in temperate forests and tropical rainforests. Boreal forests lack the layered forest structure seen in tropical rainforests or, to a lesser degree, temperate forests. The structure of a boreal forest is often only a tree layer and a ground layer. When conifer needles are dropped, they decompose more slowly than broad leaves; therefore, fewer nutrients are returned to the soil to fuel plant growth.

The Arctic tundra lies north of the subarctic boreal forests and is located throughout the Arctic regions of the Northern Hemisphere. Tundra also exists at elevations above the tree line on mountains. The average winter temperature is –34°C (–29.2°F) and the average summer temperature is 3°C–12°C (37°F –52°F). Plants in the Arctic tundra have a short growing season of approximately 50–60 days. However, there are almost 24 hours of daylight during this time, and plant growth is rapid. The annual precipitation of the Arctic tundra is low (15–25 cm or 6–10 in), with little annual variation in precipitation. And, as in the boreal forests, there is little evaporation because of the cold temperatures.

Plants in the Arctic tundra are generally low to the ground and include low shrubs, grasses, lichens, and small flowering plants (Figure 11 below). There is little species diversity, low net primary productivity, and low above-ground biomass. The Arctic tundra soils may remain in a perennially frozen state called permafrost. The permafrost makes it impossible for roots to penetrate far into the soil and slows the decay of organic matter, which inhibits the release of nutrients from organic matter. The melting of the permafrost in the brief summer provides water for a burst of productivity while temperatures and long days permit it. During the growing season, the ground of the Arctic tundra can be completely covered with plants or lichens.

Suggested Supplementary Reading

HHMI. 2018. Biome Viewer. [Interactive Website]. Howard Hughes Medical Institute. <https://www.hhmi.org/biointeractive/biomeviewer>