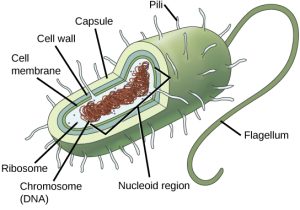

Components of Prokaryotic Cells

All cells share four common components: 1) a plasma membrane, an outer covering that separates the cell’s interior from its surrounding environment; 2) cytoplasm, consisting of a jelly-like cytosol within the cell in which there are other cellular components; 3) DNA, the cell’s genetic material; and 4) ribosomes, which synthesize proteins. However, prokaryotes differ from eukaryotic cells in several ways.

A prokaryote is a simple, mostly single-celled (unicellular) organism that lacks a nucleus, or any other membrane-bound organelle. We will shortly come to see that this is significantly different in eukaryotes. Prokaryotic DNA is in the cell’s central part: the nucleoid (Figure 4.5).

Most prokaryotes have a peptidoglycan cell wall and many have a polysaccharide capsule (Figure 4.5). The cell wall acts as an extra layer of protection, helps the cell maintain its shape, and prevents dehydration. The capsule enables the cell to attach to surfaces in its environment. Some prokaryotes have flagella, pili, or fimbriae. Flagella are used for locomotion. Pili exchange genetic material during conjugation, the process by which one bacterium transfers genetic material to another through direct contact. Bacteria use fimbriae to attach to a host cell.

Career Connection

Microbiologist

The most effective action anyone can take to prevent the spread of contagious illnesses is to wash their hands. Why? Because microbes (organisms so tiny that they can only be seen with microscopes) are ubiquitous. They live on doorknobs, money, your hands, and many other surfaces. If someone sneezes into his hand and touches a doorknob, and afterwards you touch that same doorknob, the microbes from the sneezer’s mucus are now on your hands. If you touch your hands to your mouth, nose, or eyes, those microbes can enter your body and could make you sick.

However, not all microbes (also called microorganisms) cause disease; most are actually beneficial. You have microbes in your gut that make vitamin K. Other microorganisms are used to ferment beer and wine.

Microbiologists are scientists who study microbes. Microbiologists can pursue a number of careers. Not only do they work in the food industry, they are also employed in the veterinary and medical fields. They can work in the pharmaceutical sector, serving key roles in research and development by identifying new antibiotic sources that can treat bacterial infections.

Environmental microbiologists may look for new ways to use specially selected or genetically engineered microbes to remove pollutants from soil or groundwater, as well as hazardous elements from contaminated sites. We call using these microbes bioremediation technologies. Microbiologists can also work in the bioinformatics field, providing specialized knowledge and insight for designing, developing, and specificity of computer models of, for example, bacterial epidemics.

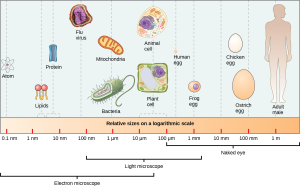

Cell Size

At 0.1 to 5.0 μm in diameter, prokaryotic cells are significantly smaller than eukaryotic cells, which have diameters ranging from 10 to 100 μm (Figure 4.6). The prokaryotes’ small size allows ions and organic molecules that enter them to quickly diffuse to other parts of the cell. Similarly, any wastes produced within a prokaryotic cell can quickly diffuse. This is not the case in eukaryotic cells, which have developed different structural adaptations to enhance intracellular transport.

Small size, in general, is necessary for all cells, whether prokaryotic or eukaryotic. Let’s examine why that is so. First, we’ll consider the area and volume of a typical cell. Not all cells are spherical in shape, but most tend to approximate a sphere. You may remember from your high school geometry course that the formula for the surface area of a sphere is 4πr2, while the formula for its volume is 4πr3/3. Thus, as the radius of a cell increases, its surface area increases as the square of its radius, but its volume increases as the cube of its radius (much more rapidly). Therefore, as a cell increases in size, its surface area-to-volume ratio decreases. This same principle would apply if the cell had a cube shape (Figure 4.7). If the cell grows too large, the plasma membrane will not have sufficient surface area to support the rate of diffusion required for the increased volume. In other words, as a cell grows, it becomes less efficient. One way to become more efficient is to divide. Other ways are to increase surface area by foldings of the cell membrane, become flat or thin and elongated, or develop organelles that perform specific tasks. These adaptations lead to developing more sophisticated cells, which we call eukaryotic cells.

Link to Learning

Surface Area to Volume Ratio Explained by Science Sauce

Visual Connection

Prokaryotic cells are much smaller than eukaryotic cells. What advantages might small cell size confer on a cell? What advantages might large cell size have?