4.5 The Cytoskeleton

Mary Ann Clark; Jung Choi; and Matthew Douglas

Microfilaments

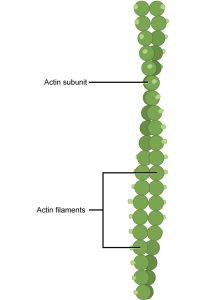

Of the three types of protein fibers in the cytoskeleton, microfilaments are the narrowest. They function in cellular movement, have a diameter of about 7 nm, and are comprised of two globular protein intertwined strands, which we call actin (Figure 4.23). For this reason, we also call microfilaments actin filaments.

ATP powers actin to assemble its filamentous form, which serves as a track for the movement of a motor protein we call myosin. This enables actin to engage in cellular events requiring motion, such as cell division in eukaryotic cells and cytoplasmic streaming, which is the cell cytoplasm’s circular movement in plant cells. Actin and myosin are plentiful in muscle cells. When your actin and myosin filaments slide past each other, your muscles contract.

Microfilaments also provide some rigidity and shape to the cell. They can depolymerize (disassemble) and reform quickly, thus enabling a cell to change its shape and move. White blood cells (your body’s infection-fighting cells) make good use of this ability. They can move to an infection site and phagocytize the pathogen.

Link to Learning

To see an example of a white blood cell in action, watch a short time-lapse video of the cell capturing two bacteria. It engulfs one and then moves on to the other.

Intermediate Filaments

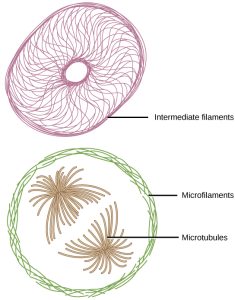

Several strands of fibrous proteins that are wound together comprise intermediate filaments (Figure 4.24). Cytoskeleton elements get their name from the fact that their diameter, 8 to 10 nm, is between those of microfilaments and microtubules.

Intermediate filaments have no role in cell movement. Their function is purely structural. They bear tension, thus maintaining the cell’s shape, and anchor the nucleus and other organelles in place. Figure 4.22 shows how intermediate filaments create a supportive scaffolding inside the cell.

The intermediate filaments are the most diverse group of cytoskeletal elements. Several fibrous protein types are in the intermediate filaments. You are probably most familiar with keratin, the fibrous protein that strengthens your hair, nails, and the skin’s epidermis.

Microtubules

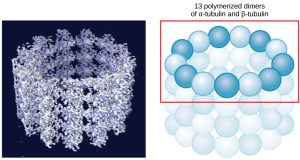

As their name implies, microtubules are small hollow tubes. Polymerized dimers of α-tubulin and β-tubulin, two globular proteins, comprise the microtubule’s walls (Figure 4.25). With a diameter of about 25 nm, microtubules are cytoskeletons’ widest components. They help the cell resist compression, provide a track along which vesicles move through the cell, and pull replicated chromosomes to opposite ends of a dividing cell. Like microfilaments, microtubules can disassemble and reform quickly.

Microtubules are also the structural elements of flagella, cilia, and centrioles (the latter are the centrosome’s two perpendicular bodies). In animal cells, the centrosome is the microtubule-organizing center. In eukaryotic cells, flagella and cilia are quite different structurally from their counterparts in prokaryotes, as we discuss below.

Flagella and Cilia

The flagella (singular = flagellum) are long, hair-like structures that extend from the plasma membrane and enable an entire cell to move (for example, sperm, Euglena, and some prokaryotes). When present, the cell has just one flagellum or a few flagella. However, when cilia (singular = cilium) are present, many of them extend along the plasma membrane’s entire surface. They are short, hair-like structures that move entire cells (such as paramecia) or substances along the cell’s outer surface (for example, the cilia of cells lining the Fallopian tubes that move the ovum toward the uterus, or cilia lining the cells of the respiratory tract that trap particulate matter and move it toward your nostrils.)

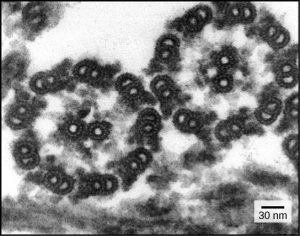

Despite their differences in length and number, flagella and cilia share a common structural arrangement of microtubules called a “9 + 2 array.” This is an appropriate name because a single flagellum or cilium is made of a ring of nine microtubule doublets, surrounding a single microtubule doublet in the center (Figure 4.26).

You have now completed a broad survey of prokaryotic and eukaryotic cell components. For a summary of cellular components in prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells, see Table 4.1.

Table 4.1 Components of Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic Cells

| Cell Component | Function | Present in Prokaryotes? | Present in Animal Cells? | Present in Plant Cells? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma membrane | Separates cell from external environment; controls passage of organic molecules, ions, water, oxygen, and wastes into and out of cell | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Cytoplasm | Provides turgor pressure to plant cells as fluid inside the central vacuole; site of many metabolic reactions; medium in which organelles are found | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Nucleolus | Darkened area within the nucleus where ribosomal subunits are synthesized. | No | Yes | Yes |

| Nucleus | Cell organelle that houses DNA and directs synthesis of ribosomes and proteins | No | Yes | Yes |

| Ribosomes | Protein synthesis | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Mitochondria | ATP production/cellular respiration | No | Yes | Yes |

| Peroxisomes | Oxidize and thus break down fatty acids and amino acids, and detoxify poisons | No | Yes | Yes |

| Vesicles and vacuoles | Storage and transport; digestive function in plant cells | No | Yes | Yes |

| Centrosome | Unspecified role in cell division in animal cells; microtubule source in animal cells | No | Yes | No |

| Lysosomes | Digestion of macromolecules; recycling of worn-out organelles | No | Yes | Some |

| Cell wall | Protection, structural support, and maintenance of cell shape | Yes, primarily peptidoglycan | No | Yes, primarily cellulose |

| Chloroplasts | Photosynthesis | No | No | Yes |

| Endoplasmic reticulum | Modifies proteins and synthesizes lipids | No | Yes | Yes |

| Golgi apparatus | Modifies, sorts, tags, packages, and distributes lipids and proteins | No | Yes | Yes |

| Cytoskeleton | Maintains cell’s shape, secures organelles in specific positions, allows cytoplasm and vesicles to move within cell, and enables unicellular organisms to move independently | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Flagella | Cellular locomotion | Some | Some | No, except for some plant sperm cells |

| Cilia | Cellular locomotion, movement of particles along plasma membrane’s extracellular surface, and filtration | Some | Some | No |