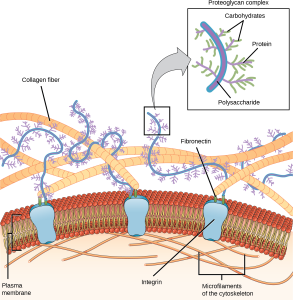

Extracellular Matrix of Animal Cells

While cells in most multicellular organisms release materials into the extracellular space, animal cells will be discussed as an example. The primary components of these materials are proteins, and the most abundant protein is collagen. Collagen fibers are interwoven with proteoglycans, which are carbohydrate-containing protein molecules. Collectively, we call these materials the extracellular matrix (Figure 4.27). Not only does the extracellular matrix hold the cells together to form a tissue, but it also allows the cells within the tissue to communicate with each other. How can this happen?

Cells have protein receptors on their plasma membranes’ extracellular surfaces. When a molecule within the matrix binds to the receptor, it changes the receptor’s molecular structure. The receptor, in turn, changes the microfilaments’ conformation positioned just inside the plasma membrane. These conformational changes induce chemical signals inside the cell that reach the nucleus and turn “on” or “off” the transcription of specific DNA sections, which affects the associated protein production, thus changing the activities within the cell.

Blood clotting provides an example of the extracellular matrix’s role in cell communication. When the cells lining a blood vessel are damaged, they display a protein receptor, which we call tissue factor. When tissue factor binds with another factor in the extracellular matrix, it causes platelets to adhere to the damaged blood vessel’s wall, stimulates the adjacent smooth muscle cells in the blood vessel to contract (thus constricting the blood vessel), and initiates a series of steps that stimulate the platelets to produce clotting factors.

Intercellular Junctions

Cells can also communicate with each other via direct contact, or intercellular junctions. There are differences in the ways that plant and animal and fungal cells communicate. Plasmodesmata are junctions between plant cells; whereas, animal cell contacts include tight junctions, gap junctions, and desmosomes.

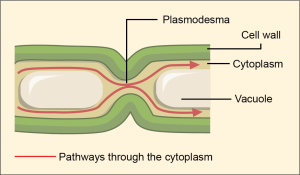

Plasmodesmata

In general, long stretches of the plasma membranes of neighboring plant cells cannot touch one another because the cell wall that surrounds each cell separates them (Figure 4.8). How then, can a plant transfer water and other soil nutrients from its roots, through its stems, and to its leaves? Such transport uses the vascular tissues (xylem and phloem) primarily. There also exist structural modifications, which we call plasmodesmata (singular = plasmodesma). Numerous channels that pass between adjacent plant cells’ cell walls connect their cytoplasm, and enable transport of materials from cell to cell, and thus throughout the plant (Figure 4.28).

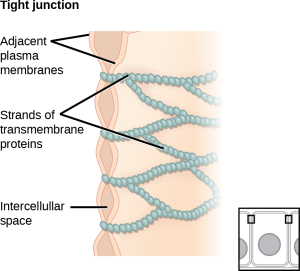

Tight Junctions

A tight junction is a watertight seal between two adjacent animal cells (Figure 4.29). Proteins (predominantly two proteins called claudins and occludins) tightly hold the cells against each other.

This tight adherence prevents materials from leaking between the cells; tight junctions are typically found in epithelial tissues that line internal organs and cavities, and comprise most of the skin. For example, the tight junctions of the epithelial cells lining your urinary bladder prevent urine from leaking out into the extracellular space.

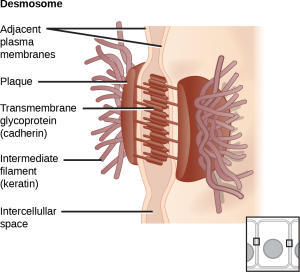

Desmosomes

Also only in animal cells are desmosomes, which act like spot welds between adjacent epithelial cells (Figure 4.30). Cadherins, short proteins in the plasma membrane connect to intermediate filaments to create desmosomes. The cadherins connect two adjacent cells and maintain the cells in a sheet-like formation in organs and tissues that stretch, like the skin, heart, and muscles.

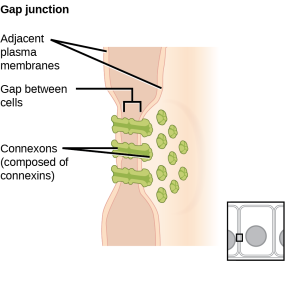

Gap Junctions

Gap junctions in animal cells are like plasmodesmata in plant cells in that they are channels between adjacent cells that allow for transporting ions, nutrients, and other substances that enable cells to communicate (Figure 4.31). Structurally, however, gap junctions and plasmodesmata differ.

Gap junctions develop when a set of six proteins (connexins) in the plasma membrane arrange themselves in an elongated donut-like configuration – a connexon. When the connexon’s pores (“doughnut holes”) in adjacent animal cells align, a channel between the two cells forms. Gap junctions are particularly important in cardiac muscle. The electrical signal for the muscle to contract passes efficiently through gap junctions, allowing the heart muscle cells to contract in tandem.