31 6.8 Mapping Genomes

Lisa Bartee; Walter Shriner; and Catherine Creech

Genomics is the study of entire genomes, including the complete set of genes, their nucleotide sequence and organization, and their interactions within a species and with other species. Genome mapping is the process of finding the locations of genes on each chromosome. The maps created by genome mapping are comparable to the maps that we use to navigate streets. A genetic map is an illustration that lists genes and their location on a chromosome. Genetic maps provide the big picture (similar to a map of interstate highways) and use genetic markers (similar to landmarks). A genetic marker is a gene or sequence on a chromosome that co-segregates (shows genetic linkage) with a specific trait. Early geneticists called this linkage analysis. Physical maps present the intimate details of smaller regions of the chromosomes (similar to a detailed road map). A physical map is a representation of the physical distance, in nucleotides, between genes or genetic markers. Both genetic linkage maps and physical maps are required to build a complete picture of the genome. Having a complete map of the genome makes it easier for researchers to study individual genes. Human genome maps help researchers in their efforts to identify human disease-causing genes related to illnesses like cancer, heart disease, and cystic fibrosis. Genome mapping can be used in a variety of other applications, such as using live microbes to clean up pollutants or even prevent pollution. Research involving plant genome mapping may lead to producing higher crop yields or developing plants that better adapt to climate change.

Genetic Maps

The study of genetic maps begins with linkage analysis, a procedure that analyzes the recombination frequency between genes to determine if they are linked or show independent assortment. The term linkage was used before the discovery of DNA. Early geneticists relied on the observation of phenotypic changes to understand the genotype of an organism. Shortly after Gregor Mendel (the father of modern genetics) proposed that traits were determined by what are now known as genes, other researchers observed that different traits were often inherited together, and thereby deduced that the genes were physically linked by being located on the same chromosome. The mapping of genes relative to each other based on linkage analysis led to the development of the first genetic maps.

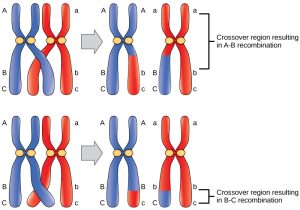

Observations that certain traits were always linked and certain others were not linked came from studying the offspring of crosses between parents with different traits. For example, in experiments performed on the garden pea, it was discovered that the color of the flower and shape of the plant’s pollen were linked traits, and therefore the genes encoding these traits were in close proximity on the same chromosome. The exchange of DNA between homologous pairs of chromosomes is called genetic recombination, which occurs by the crossing over of DNA between homologous strands of DNA, such as nonsister chromatids. Linkage analysis involves studying the recombination frequency between any two genes. The greater the distance between two genes, the higher the chance that a recombination event will occur between them, and the higher the recombination frequency between them. Two possibilities for recombination between two nonsister chromatids during meiosis are shown in Figure 1. If the recombination frequency between two genes is less than 50 percent, they are said to be linked.

The generation of genetic maps requires markers, just as a road map requires landmarks (such as rivers and mountains). Early genetic maps were based on the use of known genes as markers. More sophisticated markers, including those based on non-coding DNA, are now used to compare the genomes of individuals in a population. Although individuals of a given species are genetically similar, they are not identical; every individual has a unique set of traits. These minor differences in the genome between individuals in a population are useful for the purposes of genetic mapping. In general, a good genetic marker is a region on the chromosome that shows variability or polymorphism (multiple forms) in the population.

Some genetic markers used in generating genetic maps are restriction fragment length polymorphisms (RFLP), variable number of tandem repeats (VNTRs), microsatellite polymorphisms, and the single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). RFLPs (sometimes pronounced “rif-lips”) are detected when the DNA of an individual is cut with a restriction endonuclease that recognizes specific sequences in the DNA to generate a series of DNA fragments, which are then analyzed by gel electrophoresis. The DNA of every individual will give rise to a unique pattern of bands when cut with a particular set of restriction endonucleases; this is sometimes referred to as an individual’s DNA “fingerprint.” Certain regions of the chromosome that are subject to polymorphism will lead to the generation of the unique banding pattern. VNTRs are repeated sets of nucleotides present in the non-coding regions of DNA. Non-coding, or “junk,” DNA has no known biological function; however, research shows that much of this DNA is actually transcribed. While its function is uncertain, it is certainly active, and it may be involved in the regulation of coding genes. The number of repeats may vary in individual organisms of a population. Microsatellite polymorphisms are similar to VNTRs, but the repeat unit is very small. SNPs are variations in a single nucleotide.

Because genetic maps rely completely on the natural process of recombination, mapping is affected by natural increases or decreases in the level of recombination in any given area of the genome. Some parts of the genome are recombination hotspots, whereas others do not show a propensity for recombination. For this reason, it is important to look at mapping information developed by multiple methods.

Physical Maps

A physical map provides detail of the actual physical distance between genetic markers, as well as the number of nucleotides. There are three methods used to create a physical map: cytogenetic mapping, radiation hybrid mapping, and sequence mapping. Cytogenetic mapping uses information obtained by microscopic analysis of stained sections of the chromosome (Figure 2). It is possible to determine the approximate distance between genetic markers using cytogenetic mapping, but not the exact distance (number of base pairs). Radiation hybrid mapping uses radiation, such as x-rays, to break the DNA into fragments. The amount of radiation can be adjusted to create smaller or larger fragments. This technique overcomes the limitation of genetic mapping and is not affected by increased or decreased recombination frequency. Sequence mapping resulted from DNA sequencing technology that allowed for the creation of detailed physical maps with distances measured in terms of the number of base pairs. The creation of genomic libraries and complementary DNA (cDNA) libraries (collections of cloned sequences or all DNA from a genome) has sped up the process of physical mapping. A genetic site used to generate a physical map with sequencing technology (a sequence-tagged site, or STS) is a unique sequence in the genome with a known exact chromosomal location. An expressed sequence tag (EST) and a single sequence length polymorphism (SSLP) are common STSs. An EST is a short STS that is identified with cDNA libraries, while SSLPs are obtained from known genetic markers and provide a link between genetic maps and physical maps.

Integration of Genetic and Physical Maps

Genetic maps provide the outline and physical maps provide the details. It is easy to understand why both types of genome mapping techniques are important to show the big picture. Information obtained from each technique is used in combination to study the genome. Genomic mapping is being used with different model organisms that are used for research. Genome mapping is still an ongoing process, and as more advanced techniques are developed, more advances are expected. Genome mapping is similar to completing a complicated puzzle using every piece of available data. Mapping information generated in laboratories all over the world is entered into central databases, such as GenBank at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). Efforts are being made to make the information more easily accessible to researchers and the general public. Just as we use global positioning systems instead of paper maps to navigate through roadways, NCBI has created a genome viewer tool to simplify the data-mining process.

References

Unless otherwise noted, images on this page are licensed under CC-BY 4.0 by OpenStax.

OpenStax, Biology. OpenStax CNX. January 2, 2017 https://cnx.org/contents/GFy_h8cu@10.120:Qq6Y1A16@5/Mapping-Genomes