8

Christine Angel

Gina Marandino

Introduction

How does one take an existing face-to-face museum informatics course that includes in-person museum field trips and redesign it to provide equitable access and flexibility for students within the online learning environment without sacrificing the high quality of discourse and real-world experiences that a traditional face-to-face course provides? One faculty member needed to find a solution to this question when the Division of Library and Information Science (DLIS) program at St. John’s University moved their master’s degree from the face-to-face to the online learning environment.

When the museum informatics course was initially designed, it was constructed for the face-to-face learning environment and included required museum field trips. These field trips were crucial to the course design because they provided students with real-world experiences and knowledge that they need to have when working in the field. As Tuthill and Klemm note, “Field trips help bridge formal and informal learning and prepare students for lifelong learning” (2002, p. 453). The formal learning of the museum field trips aligned with self-assigned student–museum partnership assignments relating to four museum benchmarks. The field trips also provided places of informal learning for students because they were able to observe the organic interactions between and among people, information, and technology within the museum environment.

When the DLIS graduate program moved online, these real-world student–museum interactions were lost. So, the question became one of how to translate these face-to-face student–museum interactions to the online learning environment while maintaining the same amount of student engagement that is traditionally found within a face-to-face course. To resolve the problem, field trips were provided to students using video, with the help of a New Media and Communications Specialist from the University’s Department of Online Learning and Services. The advantage of incorporating video into the museum field trips is that “the quality of interactions among students and the instructor relates less to geographical separation and more to the degree of flexibility in the structure of a course, the degree of dialogue and interactions that take place within it, and the degree of learner autonomy” (M. Moore, cited in Dolan, Kain, Reilly & Bansal, 2017, p. 46).

This chapter first describes the museum informatics course and its corresponding social media tools. The role of the New Media and Communications Specialist is then described along with the digital media tools leveraged when assisting the faculty member in transforming the course for the online learning environment. Examples of barriers encountered, and technologies used to overcome these barriers are then described. Student assignment examples are provided, and the chapter concludes with a summary of student feedback obtained from post-course reflections relating to their online classroom experiences.

Background

“One of the challenges in offering online education is to simulate the dynamics of the face-to-face (f2f) classroom environment in which much of the learning process takes place” (Draus, Curran, & Trempus, 2014, p. 240). The challenge lies in the fact that within the online environment there is a “separation between the instructor and the learning and between the learners and each other” (Lehman & Conceição, 2010, p. 2). This can result in feelings of isolation among the students and faculty within “the learning environment, which can negatively affect satisfaction and learning through a lack of interest and loss of motivation” (Costley & Lange, 2017, pp. 14–15).

The authors of this chapter thought it timely to reflect upon the challenges of creating online course content as the DLIS program at St. John’s University recently became fully online. The trickle effect of this programmatic change within the division meant that the faculty member responsible for museum informatics was required to adapt the course, which was originally constructed for the face-to-face classroom environment, to the online learning environment. This challenged them to (re)think how to design online course content to ensure the same quality, connectivity, and peer engagement that a student would experience within a more traditional face-to-face learning environment (Croft, Dalton, & Grant, 2010).

Through collaboration with a media specialist, the faculty member was able to tackle this challenge head-on using social and digital media. When used properly, social and digital media have the potential to address issues such as decreased student satisfaction and engagement “by improving perceptions of instructor presence that may compensate for the lack of physical interaction between teaching and students” (Costley & Lange, 2017, p. 15).

“While the use of technology is very important in the delivery of course content, focusing on the pedagogy of teaching online and hybrid classes is paramount when constructing a comprehensive teaching platform” (Angel, 2016, p. 4). This is especially important when one is answerable to an external accrediting agency (American Library Association, 2019). According to the Council for Higher Education Accreditation (CHEA), “Accreditation is a process of external quality review created and used by higher education to scrutinize institutions and programs for quality assurance and quality improvement” (2019, p. 2).

Demonstrated quality within accredited Library and Information Studies programs is assessed, most notably, through student achievement of eight pre-defined American Library Association (ALA) Core Competencies (American Library Association Council, 2009). Therefore, “to ensure educational quality, [which is] judged in terms of demonstrated results . . . of student [achievement]” (American Library Association Council, 2019, p. 1) it was necessary to crosswalk the museum informatics course from one (or more) of the eight ALA Core Competencies to the appropriate professional standards and best practices pertaining to the management of recorded information within the museum environment.

The Museum Informatics Course Structure

The adoption of information technology within the museum environment has transformed the traditional brick-and-mortar “repositories of objects . . . [to] repositories of knowledge” (Marty, 2010, p. 3717). This means that within the technologically connected and service-oriented museum of today, “information about museum collections is just as important as the collections themselves” (Marty, 2010, p. 3717). Thus, to provide information about a museum’s collection(s) to its users, it became crucial to ensure museum professionals possessed the necessary skill set to manage this information, both online and physically within the institution. As such, a new profession emerged, called museum informatics (Marty, 2010; Marty & Jones, 2008).

According to Marty (2008, p. 3), “museum informatics is the study of the sociotechnical interactions that take place at the intersection of people, information, and technology in museums.” Within the museum informatics course, students explore the use of information technology in museums and the ways in which modern information systems have (re)shaped the museum environment, by focusing on four main blocks of study: (a) access, (b) interactive, (c) social media, and (d) legal. Through these four blocks of study, students demonstrate mastery of the information professional’s role within the museum environment in managing recorded knowledge and disseminating it between and among information, people, and technology.

For students to be able to demonstrate achievement of information management within the museum environment, the course was designed to include four blocks of study coinciding with the National Standards & Best Practices for U.S. Museums (Merritt, 2008). A subset of these standards was then crosswalked to the Core Competencies for Visual Resources Management (Iyer, 2007) which are supported by the Visual Resources Association (2018). These competencies were then crosswalked with the Art Libraries Society of North America (ARLIS/NA) Core Competencies (Stafford, Portis, Andres, & Henri, 2017). From these standards and best practices, five course objectives and associated learning outcomes were identified, along with corresponding assessments. The corresponding assessments are the artifacts used within the course to demonstrate student understanding of the information professional’s role within the museum environment. To close the loop between museum standards and best practices and the core competencies recognized by the ALA, the five identified course objectives, the associated student learning objectives, and the assessments were crosswalked to the four corresponding ALA Core Competencies and their associated sub-competencies, which are outlined in Table 1.

Summary table linking assessments to student learning outcomes, course objectives, and American Library Association (ALA) core competencies.

|

ALA core competencies |

Course objectives |

Learning outcomes |

Assessments |

|

8. Administration and management8C. The concepts behind, and methods for, assessment and evaluation of museum services and their outcomes. |

#1: To equip students with the basic concepts and terminology of museum informatics. |

#1: Upon completion of this course, students will be able to demonstrate knowledge of the basic concepts and terminology used within the field of museum informatics. |

Info-Matic Blog ProjectComparative analysis of information management systems [access block of study] |

|

1. Foundations of the profession1G. The legal framework within which museums and information agencies operate. That framework includes laws relating to copyright, privacy, freedom of expression, equal rights (e.g., the Americans with Disabilities Act), and intellectual property. |

#2: To provide students with an opportunity to explore the modern museum as an information environment, understanding issues such as intellectual property and copyright. |

#2: Upon completion of this course, students will be able to describe how the modern museum acts as an information environment by demonstrating comprehension of issues such as intellectual property and copyright. |

Copyright assignment [legal block of study] |

|

3. Organization of recorded knowledge and information3B. The developmental, descriptive and evaluative skills needed to organize recorded knowledge and information. |

#3: To equip students with a basic skill set to effectively deal with challenges within the field of museum informatics as they develop and manage digital collections to include: (a) information organization and access, (b) digitization and computer automation, and (c) standards for data sharing. |

#3: Upon completion of this course, students will be able to define and provide examples of challenges facing museum information professionals as they develop digital collections, including information organization and access, digitization and computer automation, and standards for data sharing. |

Info-Matic Blog ProjectDublin Core (DC) Metadata Assignment [access block of study] Self-selected student–museum partner observation [access block of study] |

|

4. Technological knowledge and skills4C. The methods of assessing and evaluating the specifications, efficacy, and cost efficiency of technology-based products and services.4D. The principles and techniques necessary to identify and analyze emerging technologies and innovations to recognize and implement relevant technological improvements. |

#4: To provide students with the skill set necessary to evaluate the impact of interactive technologies on museum information professionals, from the perspectives of (a) museum–museum collaborations, (b) museum–school educational outreach, and (c) museum–scholar research activities. |

#4: Upon completion of this course, students will be able to critically analyze the impact of interactive technologies on museum information professionals from the the perspectives of (a) museum–museum collaborations, (b) museum–school educational outreach, and (c) museum–scholar research activities. |

Interactive technology assignment [interactive block of study]Self-selected student–museum partner observation [interactive block of study] |

|

4. Technological knowledge and skills4C. The methods of assessing and evaluating the specifications, efficacy, and cost efficiency of technology-based products and services.4D. The principles and techniques necessary to identify and analyze emerging technologies and innovations to recognize and implement relevant technological improvements. |

#5: Demonstrate the social impact of information technologies on museum visitors, taking into consideration (a) multimedia exhibits within the brick-and-mortar museum, (b) virtual museums within the online environment, and (c) pervasive computing devices. |

#5: Upon completion of this course students will be able to critically analyze the social impact of museum technologies on museum visitors, taking into consideration such issues as: (a) multimedia exhibits within the brick-and-mortar museum, (b) virtual museums within the online environment, and (c) pervasive computing devices. |

Social media technology assignment [social media block of study] Self-selected student–museum partner observation [social media block of study] |

Table 1. Summary table linking assessments to student learning outcomes, course objectives, and American Library Association (ALA) core competencies.

The first task students engage in within the museum informatics course is to select one museum within their geographic location that they would like to partner with for the semester. This should not only be a museum that students enjoy visiting but also one that will allow them to complete the required assignments. The assignments are outlined in the course syllabus and coincide with the four main blocks of study. There are three different types of assignments within the museum informatics course that require student engagement—both online and face-to-face—with the student’s self-selected museum partner: (a) assignments associated with one self-identified museum object, (b) assignments associated with museum observations, and (c) a comparative analysis of three different information management systems.

The assignments associated with the student’s self-selected museum object are the copyright assignment, which is associated with the legal block of study; the Dublin Core (DC) metadata assignment, which is associated with the access block of study; the interactive technology assignment, which is associated with the interactive block of study; and the social media assignment, which is associated with the social media block of study.

There are three self-selected student–museum partner observations (see Table 1). The third and final type of assignment was a comparative analysis of three information management systems. This assignment was conducted in conjunction with a museum information professional and coincides with the access block of study

The Museum Informatics Course (Re)Design

As previously mentioned, when the museum informatics course was initially designed it was constructed for the face-to-face learning environment, with four required museum field trips. These museum field trips coincided with the four main blocks of study—or benchmarks—relating to the adoption of technology in museums: (a) access, (b) interactive, (c) social, and (d) legal. The field trips were crucial to the course design because they provided students with real-world examples of how different museum professionals adopted interactive and social technologies within their own museums, provided museum visitors with access to their collections both on-site and within the online environment, and provided examples of the legal framework within which they operated.

The field trips were also crucial to the course design because students used them as assignment examples for each benchmark relating to the adoption of technology in museums. The assignments for the course were constructed so that students would obtain an understanding of each benchmark and then provide relevant examples using a locally self-assigned museum partner. These assignments were then posted to the museum informatics course blog, “Info-Matic.Org: A DLIS Project,” which is hosted by WordPress (Version 5.1) (n.d.) and located at www.info-matic.org (Angel, 2019a; also see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The Info-Matic Blog (www.info-matic.org; home page hosted by WordPress).

The blog provided not only a venue for online students to connect with other classmates enrolled in the course, but also additional examples of how museum professionals manage their sociotechnical interactions between and among people, information, and technology. When the structure of the DLIS program changed from the traditional face-to-face format to being offered 100% online, face-to-face field trips could no longer be mandatory. This is because the online learning environment has a potentially greater geographical reach, making it impossible for faculty to require students to physically attend museum field trips. Moreover, equitable access to class instruction for all students within the online learning environment was of paramount concern when (re)addressing the course design.

The solution was to incorporate the museum field trips into the already existing Info-Matic course blog using digital media such as videos. The use of videos is crucial in an online course because their “versatility, accessibility, breadth of content, and up-to-date materials afford both instructors and students opportunities to shape and contribute to course content and increase student engagement in classroom discussions and activities” (Sherer & Shea, 2011, p. 58). Essentially, the course design remained the same, with the only change being the removal of the field trip requirement. Instead, the New Media and Communications Specialist from the University’s Online Learning and Services Department accompanied the faculty member along with any students who wished to physically participate in the museum field trips, which were video-recorded for the use of students who did not physically participate. The role of the New Media and Communications Specialist is to assist faculty with the incorporation of video and other types of media into their courses. In this case, the purpose of the media specialist’s involvement in the museum informatics course was to develop online content by filming the museum tours and conducting interviews with museum information professionals and students in attendance during the field trips.

Upon completion of the museum visit the media specialist edited the videos and provided the faculty member access to these videos through an online video streaming platform called Panopto (Panopto, Version 5.8.0 [5.8.0.37552]). The faculty member then linked the videos to the appropriate benchmark within the class blog. These videos, which demonstrated each of the four benchmarks in action, acted as real-world examples of how different types of information systems are reshaping the modern museum environment. They also acted as assignment examples for the follow-up assignments students constructed utilizing their own self-selected museum partner. These follow-up artifacts were then published by the museum informatics students to the course blog.

Benchmarks and Corresponding Field Trips

In theory, filming museum tours and visits with museum curators seemed like the best way to provide distance students with the same experiences that they would have if they visited the museum. However, some practical issues had to be addressed before the museum visits could take place. First, the faculty member had to find museums that would be open to a site visit. Additionally, the content of these site visits needed to overlap with the four benchmarks and associated assignments outlined in the course. In this way, each benchmark identified within the course would have an associated museum visit, and this visit would act as a real-world example for the associated student assignments. Four museums were identified: (a) the Holocaust Museum & Tolerance Center of Nassau County, located in Glen Cove, NY; (b) the American Museum of Natural History, located in New York, NY; (c) the National Museum of the American Indian, located in Washington, DC; and (d) the Brooklyn Museum, located in Brooklyn, NY.

Incorporating the Interactive Benchmark-in-Action

The first site visit, which took place at the Holocaust Memorial & Tolerance Center (HMTC), coincided with the interactive benchmark and provided students with a real-world example of how the HMTC incorporated interactive technologies into their museum exhibits. The videos captured at this museum included guided tours of the exhibits given by the museum curator Beth Lilach. The focus of these videos was to provide students with real-world examples of the technologies used by the HMTC that allow museum visitors to engage with exhibits, both on-site and online. Such technologies include kiosks, television tours, audio tours, maps, exhibit labels, and anything else that helps connect visitors with museum objects. Based on these guidelines, the curator selected specific exhibits to showcase. Since these videos were meant to replicate a real-world museum visit, a storyboard or script was not used. To better connect the museum tours with the course content, the tour videos were interspersed with photos of the collections to make a cohesive artifact illustrating the Interactive Benchmark-in-Action. While showing an exhibit that featured a timeline, television screens, and photos, the curator talked about how HMTC tours are designed to connect to current issues and how tours are modified based on audience.

The curator of the HMTC was very amenable to having videos and photos taken on-site. However, the poor lighting and background noise within the museum made it difficult to capture high-quality digital media. This is because the functionality of the camcorder (Samsung HMX-F90) that was used is not as flexible in terms of light settings compared to a more professional camera. Although white balance settings—which correct the presence of a blue or yellow tint—were available (Ascher & Pincus, 2013, p. 109) the camcorder did not allow for changing the aperture or shutter speed, which both affect how much light will shine on an image. The aperture, which is “a small set of blades in the lens that controls how much light will enter the camera” (Improve Photography LLC, 2017, para. 3) enables a videographer to make the shot brighter. The shutter, which is “a small ‘curtain’ in the camera that quickly rolls over the image sensor (the digital version of film) and allows light to shine onto the imaging sensor for a fraction of a second” (Improve Photography LLC, 2017, para. 7), has a speed setting tha can be turned down to allow light to shine on the images for a longer period. When modifying the image’s white balance, the media specialist selected the tungsten setting because it is optimal for filming indoors, especially in areas of low light (Ascher & Pincus, 2013, p. 110). After adjusting the camcorder, the next step was to set the microphone for optimal recording.

The microphone used for recording, the H2 Handy Recorder produced by Zoom (H2 Handy Recorder Version 1.90), is a portable microphone that records audio to a Secure Digital (SD) card and runs on AA batteries. It does not have the capability to completely block out background noise. It does, however, allow users to adjust the angle from which the microphone will capture audio. The setting options include: (a) front 90° angle, (b) rear 120° angle, and (c) surround options (Zoom, 2007, pp. 21–22). In general terms, this microphone is capable of focusing the audio on the speaker and reducing background noise. Utilizing the front 90° setting on the microphone, the media specialist was able to reduce some background noise and focus on the speaker. However, this proved to be insufficient for filming within some of the settings at the HMTC. To combat the equipment limitations and produce polished videos, the media specialist used a host of software tools from the Adobe Creative Cloud

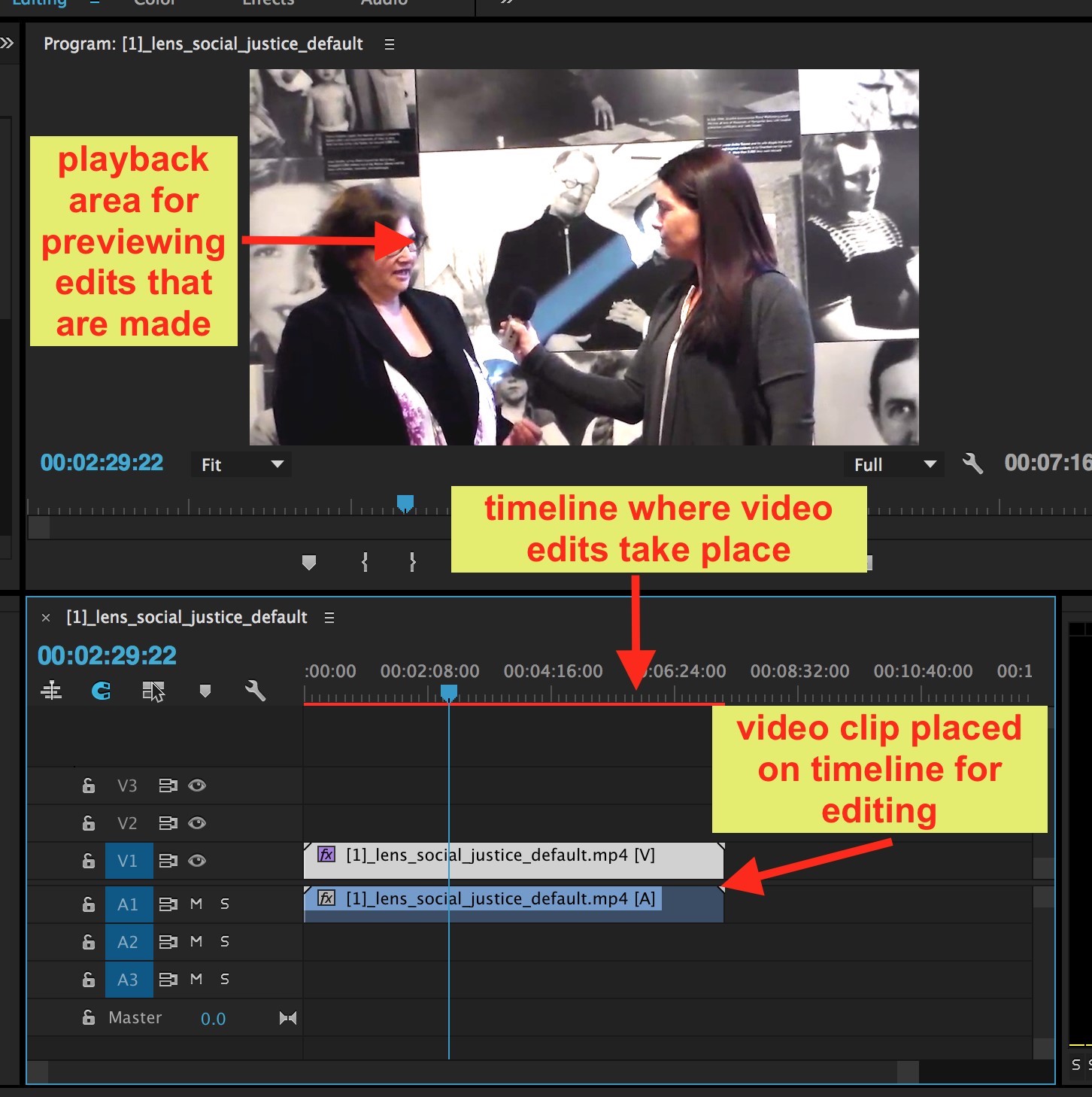

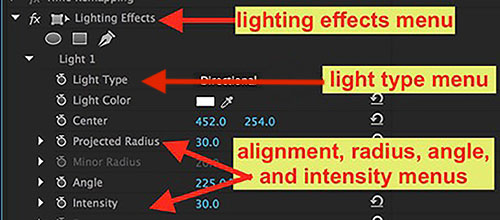

One piece of software essential to enhancing the video clips was the video editing tool Adobe Premiere Pro (Adobe Premiere Pro CC 2015, Version 9.0, Build 9.0.0 [247]). With this software, the media specialist was able to replicate the lighting effects that a lighting kit or a more advanced camera would have provided. The first step was to import the clips into Adobe Premiere Pro and place them on the timeline, the area in Adobe Premiere where all editing takes place. While making the edits, the media specialist was able to preview them and make changes as needed (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Screenshot of Adobe Premiere Pro workspace with playback area and timeline (Adobe Premiere Pro CC 2015, Version 9.0, Build 9.0.0 [247]).

Next, the lighting effects function was used to apply a directional light to the subject being filmed and adjust its alignment, radius, angle, and intensity to brighten the image (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Screenshot of Adobe Premiere Pro lighting effects menu (Adobe Premiere Pro CC 2015, Version 9.0, Build 9.0.0 [247]).

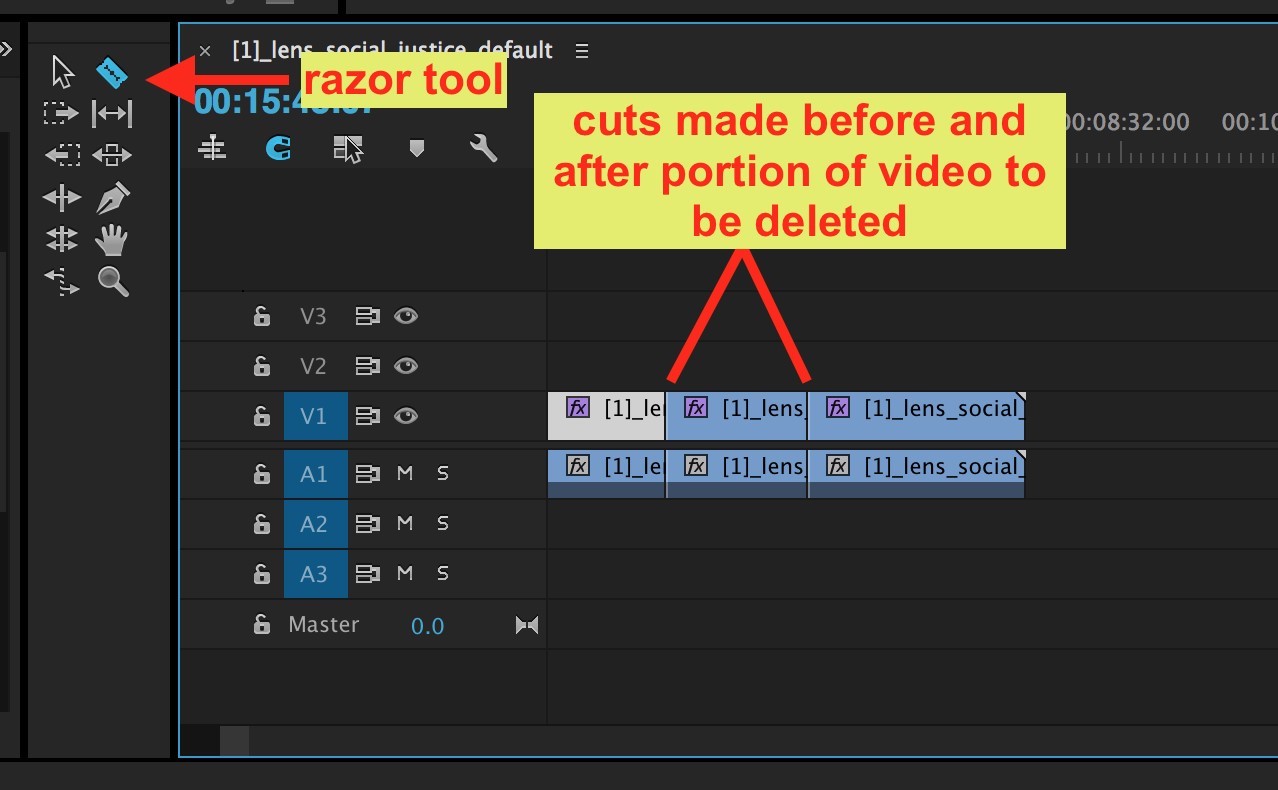

The same effects were applied to all four videos filmed at the HMTC. Next, the media specialist and the faculty member selected the portions of footage to be used for each video and removed excess footage using the Razor Tool (Adobe, 2019d) in Adobe Premiere (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Screenshot of Adobe Premiere Pro timeline showing the Razor Tool and cuts made to the video footage (Adobe Premiere Pro CC 2015, Version 9.0, Build 9.0.0 [247]).

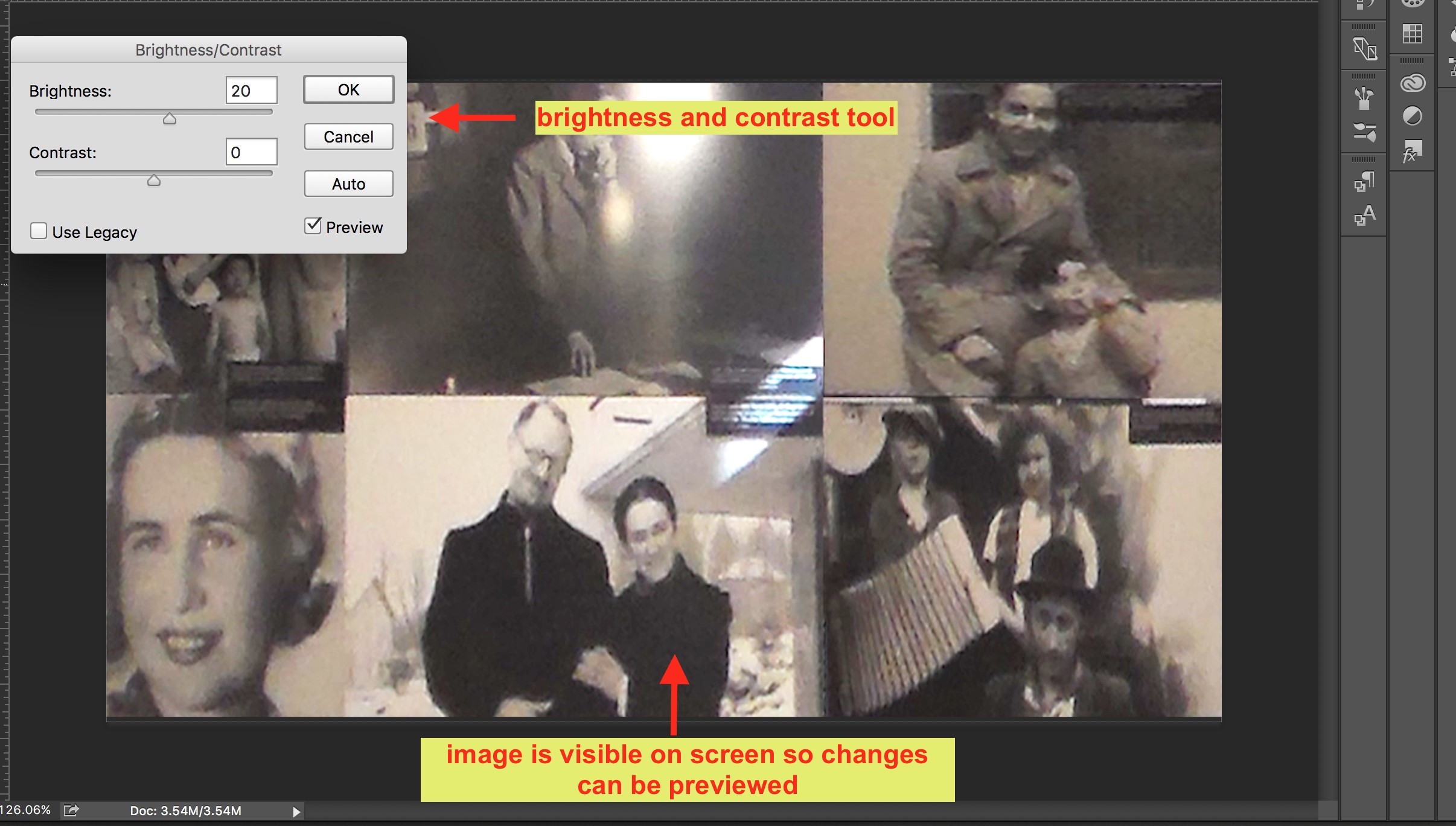

After the videos were edited, photographs were selected to be interspersed with the video footage. Since the museum was dark, some photos needed to be brightened and sharpened. To edit the photos, the media specialist used Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Photoshop CC 2015.0.0). First, the Brightness/Contrast function (Adobe, 2019c) was applied to increase or decrease the image’s pixel values as needed (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Screenshot of Adobe Photoshop showing Brightness/Contrast menu (Adobe Photoshop CC 2015.0.0).

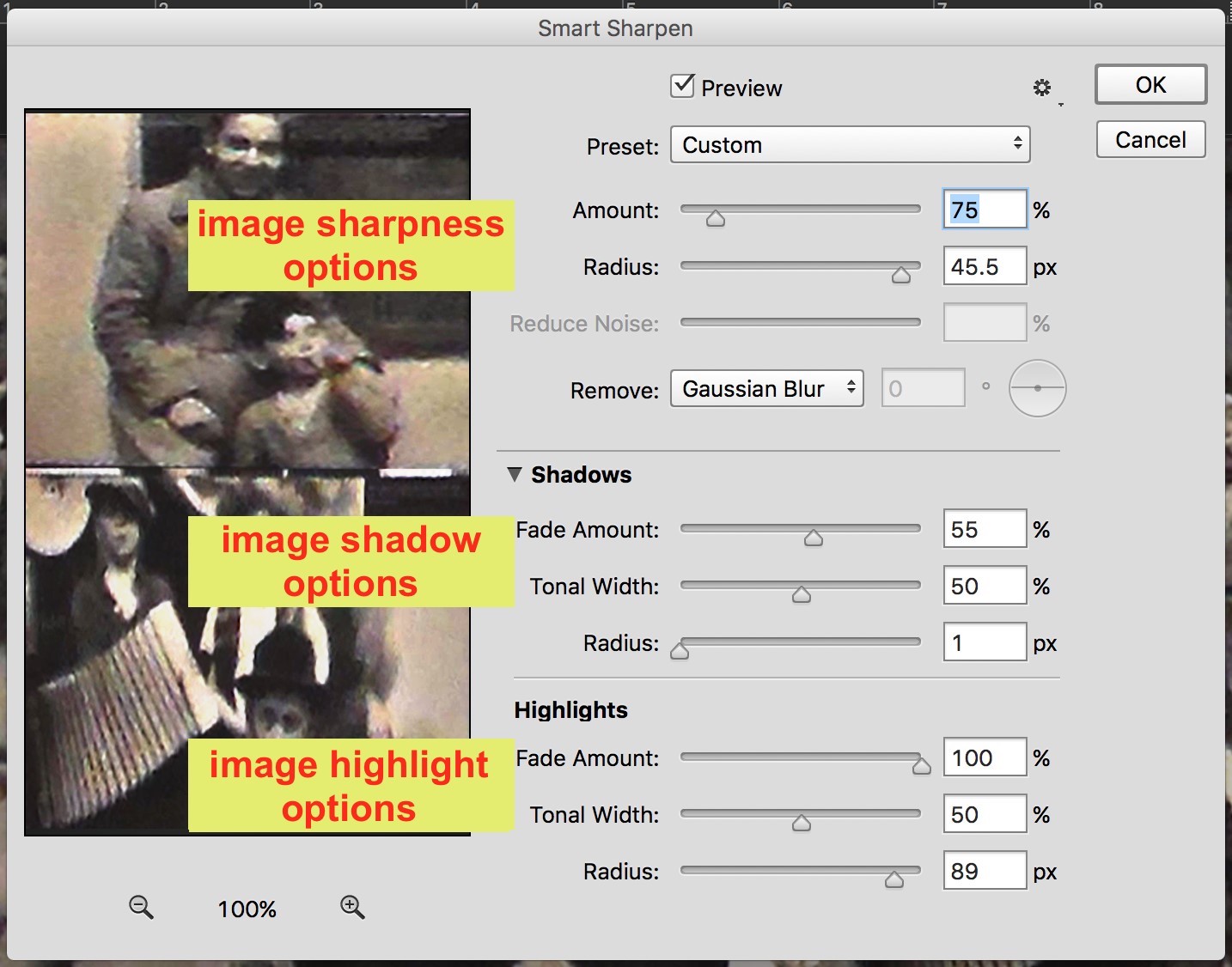

The Smart Sharpen effect (Adobe, 2019c) was then applied to adjust the images’ blurriness, sharpness, highlights, and shadows (see Figure 6).

Figure 6. Screenshot of Adobe Photoshop showing the Smart Sharpen menu (Adobe Photoshop CC 2015.0.0).

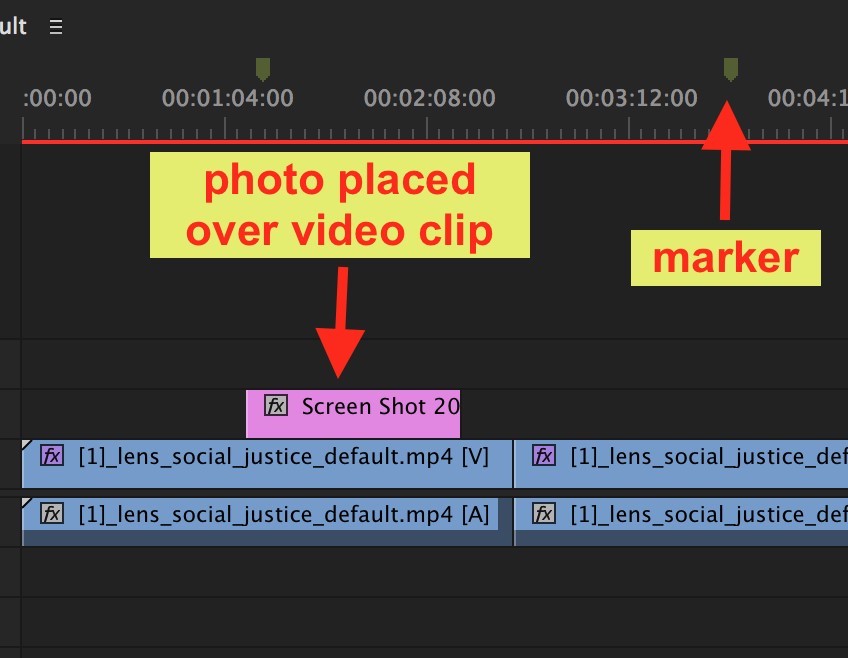

The next step was to insert the photos at appropriate times in the video. To accomplish this, the media specialist used Adobe Premiere Pro to playback each video and place markers onto the timeline where each photograph should appear. Then, the photos were imported into Adobe Premiere Pro and placed in the correct spot over the video. Lastly, the amount of time the photographs were visible was shortened or lengthened so each played for the exact length of time that the curator was speaking about it (see Figure 7).

Figure 7. Screenshot of Adobe Premiere timeline showing photo and marker placement (Adobe Premiere Pro CC, 2015, Version 9.0, Build 9.0.0 [247]).

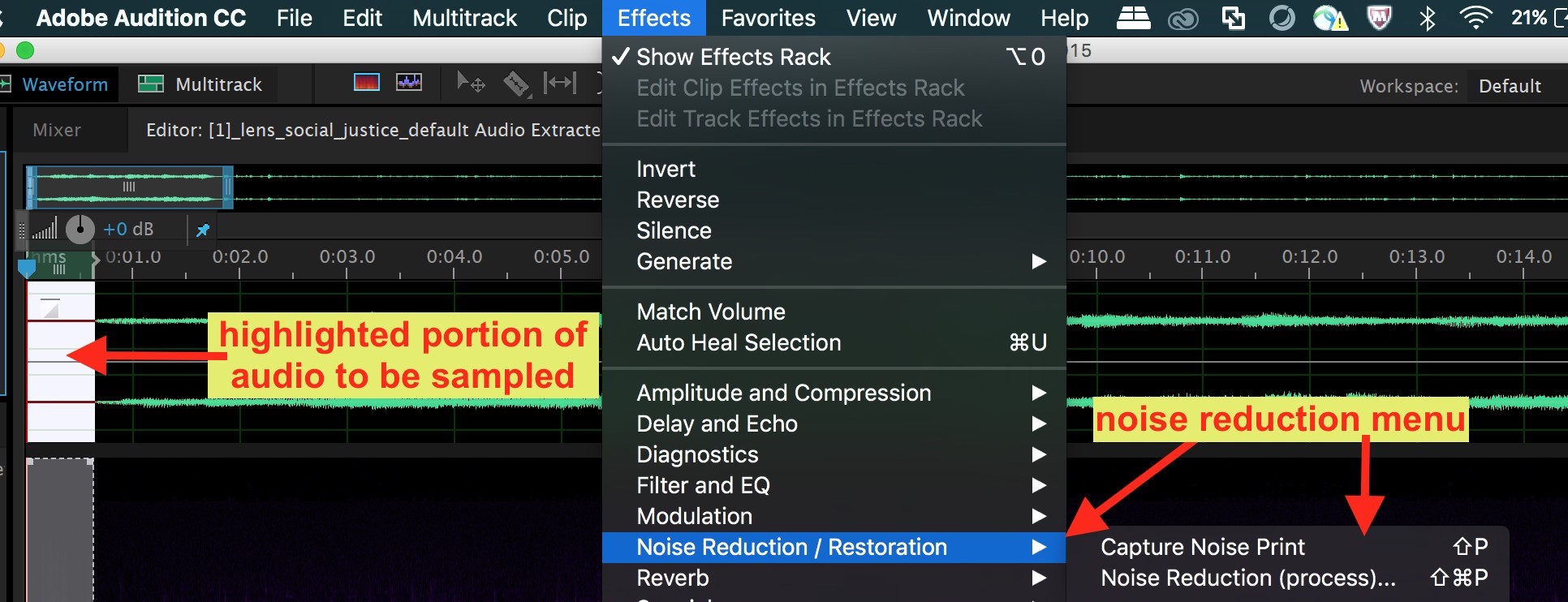

To reduce the background noise that was present in the videos, the media specialist used the audio editing software Adobe Audition (Adobe Audition CC 2015, Build 8.0.0.192). The media specialist used the Capture Noise Print feature (Adobe, 2019b) to take a sample of the background noise, and the Noise Reduction (process) effect (Adobe 2019b) to reduce the background noise (see Figure 8).

Figure 8. Screenshot of Adobe Audition noise reduction menu and highlighted portion of audio (Adobe Audition CC 2015, Build 8.0.0.192).

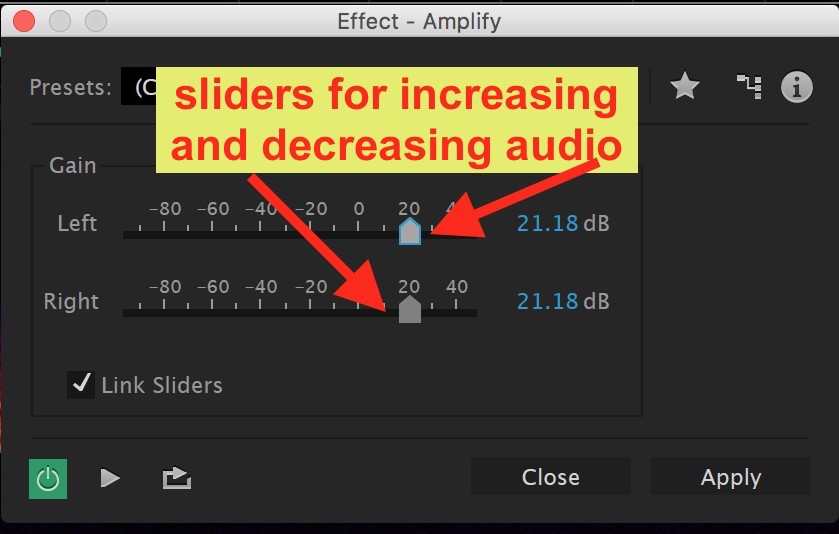

The process of reducing the background noise also reduces the foreground noise, however. To fix this, after reducing the background noise the media specialist used Adobe Audition to apply the Amplify effect (Adobe, 2019b) and set the number of decibels by which to increase the audio (see Figure 9).

Figure 9. Screenshot of Adobe Audition Amplify tool (Adobe Audition CC 2015, Build 8.0.0.192).

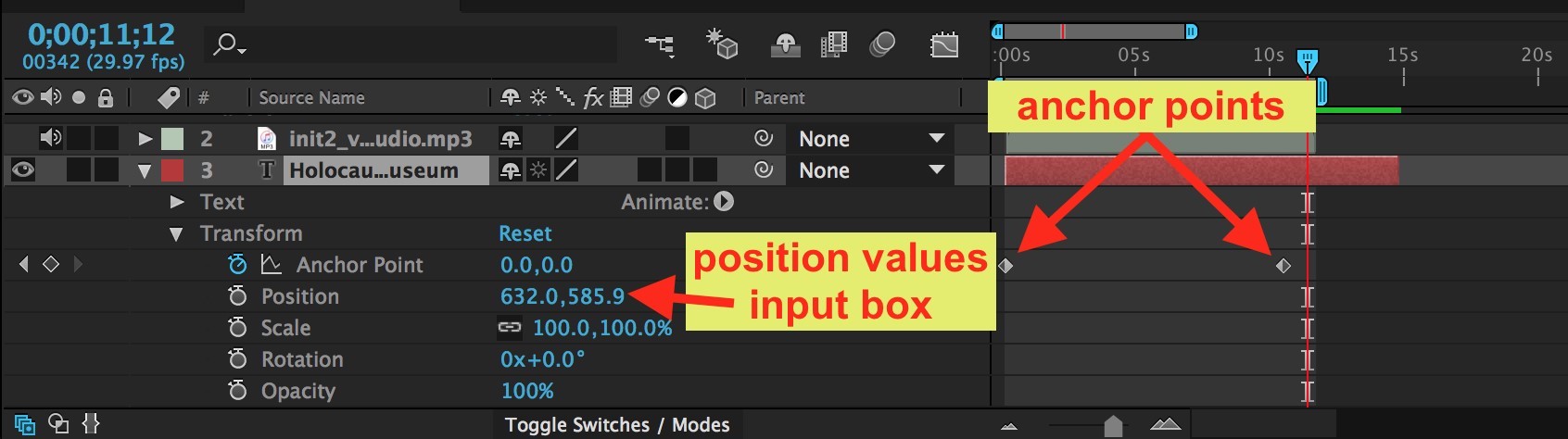

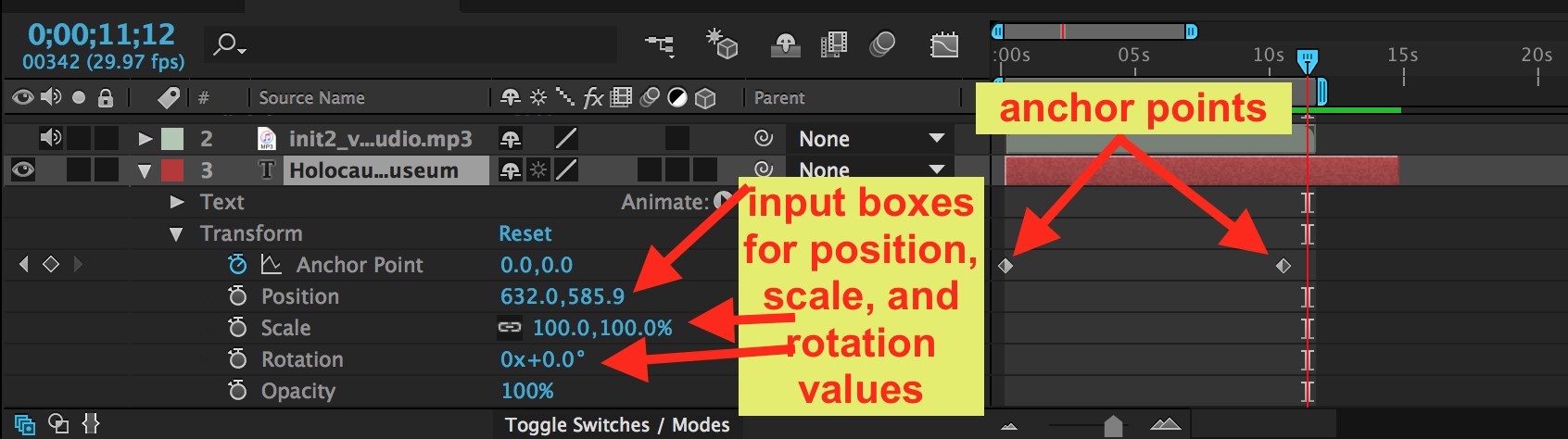

To introduce each video, the media specialist created animated titles using Adobe After Effects. The titles included text that the media specialist animated by changing the text box’s vertical position at different points in the title sequence and adding anchor points on the timeline, enabling the Adobe After Effects software to record the different positions of the text (see Figure 10).

Figure 10. Screenshot of Adobe After Effects anchor points and position tool (Adobe After Effects CC, 2015, Version 13.5.0.347).

Upon completion of editing, the media specialist uploaded the videos to the video hosting software tool Panopto to be placed on the Info-Matic Blog. The examples were then followed up with an interactive technology assignment, which provided students with the opportunity to demonstrate their knowledge about how their museum partners are creating interactive exhibits to provide their visitors—both online and on-site—with new ways of exploring their collections.

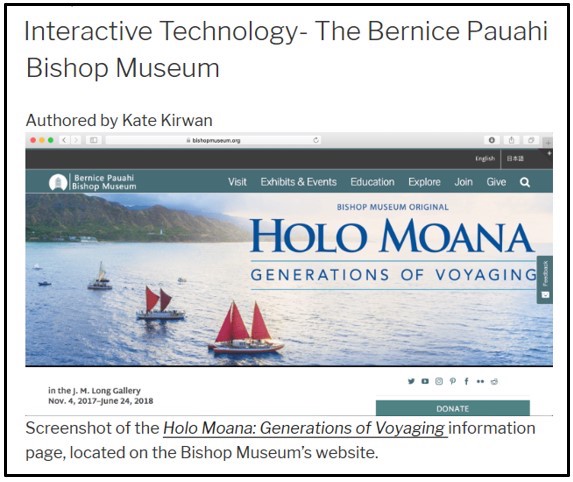

The students used the Interactive Benchmark-in-Action as a real-world example to consider how they might apply the same interactive technology concepts to their own museum-partner assignment and observation. Upon completion of the interactive technology assignment, the students were required to upload their artifacts to the corresponding student page within the Info-Matic blog, under the section titled “Interactive: Museum Access Online & Onsite.” Figure 11 shows an example of a student assignment, from the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum in Honolulu, Hawaii, demonstrating how museum information professionals can create an interactive exhibit.

Figure 11. Museum informatics interactive technology assignment example, by Kate Kirwan (http://info-matic.org/category/interactive-museum-access-online-onsite/).

Incorporating the Access Benchmark-in-Action

The second site visit took place at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) and paralleled the museum informatics class block of study titled “Access Benchmark-in-Action.” The purpose of this Benchmark-in-Action was to provide students with a real-world example of how a museum, through the use of technology, is creating greater connections with their visitors. The focus of this museum visit was to explore how the AMNH blends their digital and physical worlds. This was explained through a presentation by Mai Reitmeyer, a Senior Research Librarian at the museum. During the site visit, physical and digital artifacts were shown and how the museum integrates all its digital systems was explained. The result of the filming, photographing, and editing from this visit was a high-quality, real-world example of the Access Benchmark-in-Action.

The faculty member and media specialist faced a barrier when visiting the AMNH, because the museum did not allow filming of exhibits or staff. Photos could be taken anywhere; however, filming was restricted to the museum lobby. The question then became, How can an experience similar to a visit in person be provided to distance students if museum content cannot be filmed? Focusing on the students who joined the visit solved this problem. At the end of the museum tour, these students were interviewed on camera about their impressions of the museum, focusing on collections and artifacts that related to the topic of access.

The media specialist took photos throughout the visit and filmed student interviews in the lobby of the museum. These interview videos were not structured and did not follow a script. The students were asked to talk about artifacts they saw and relate them to the topic of access; they were free to reflect on anything they saw that day. Some topics that students reflected on were (a) how the museum connects the different content management systems used by each department, (b) the translation of information from the physical to the digital world, and (c) the opportunity for users to experience the museum online without visiting it in person. By interspersing photos and video interviews the media specialist was able to create a product that resembled a museum tour.

To record the interview video the media specialist brought the same camcorder used during the visit to the HMTC (Samsung HMX-F90). Instead of using the camcorder for capturing photos, however, the media specialist used a cell phone (an iPhone 6). The plan was to combine the video clips and photos to make a cohesive and polished video.

The first step was to import the videos and photos into the computer to see if any of the media needed to be edited. The media specialist looked at the photos first. Due to the dark lighting of the museum, some photos needed to be brightened and sharpened. The media specialist used Adobe Photoshop and applied the same brightness, contrast, and sharpen effects that were used with the HMTC photos.

Next, the media specialist reviewed the video footage. Because the videos were filmed in the museum lobby, there was a lot of background noise. The media specialist again used Adobe Audition to reduce the background noise and amplify the foreground noise.

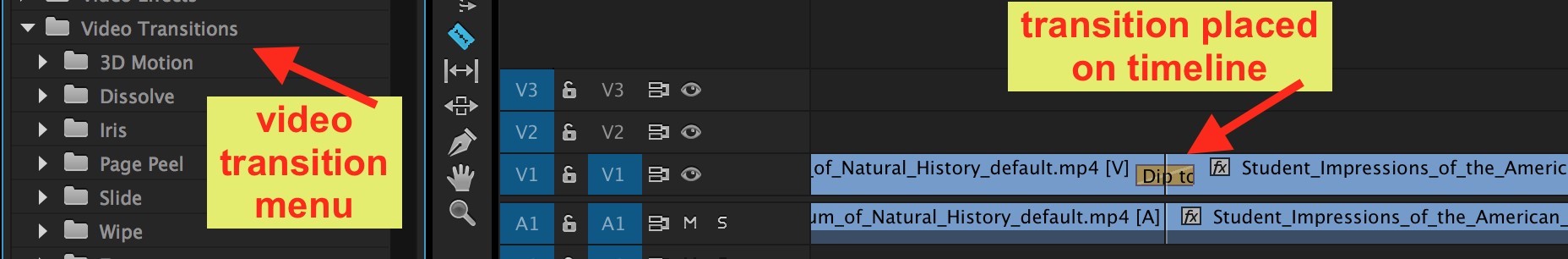

The next step was to use Adobe Premiere Pro to combine the student interviews with the photos. After dropping all the videos onto the timeline in the correct order, the media specialist repeated the procedure that was used with the HMTC videos. This involved (a) using the Razor Tool to remove excess footage, (b) inserting markers where the photos should go, (c) dropping the photos in the correct spots on the timeline, and (d) changing the length of the photo coverage so each one played for the correct amount of time. The next step was to make the series of photos and video clips look like a cohesive video. To do this, the media specialist used Adobe Premiere Pro and inserted transitions between each pair of clips on the timeline (see Figure 12).

Figure 12. Screenshot of Adobe Premiere Pro transition tool (Adobe Premiere Pro CC 2015, Version 9.0, Build 9.0.0 [247]).

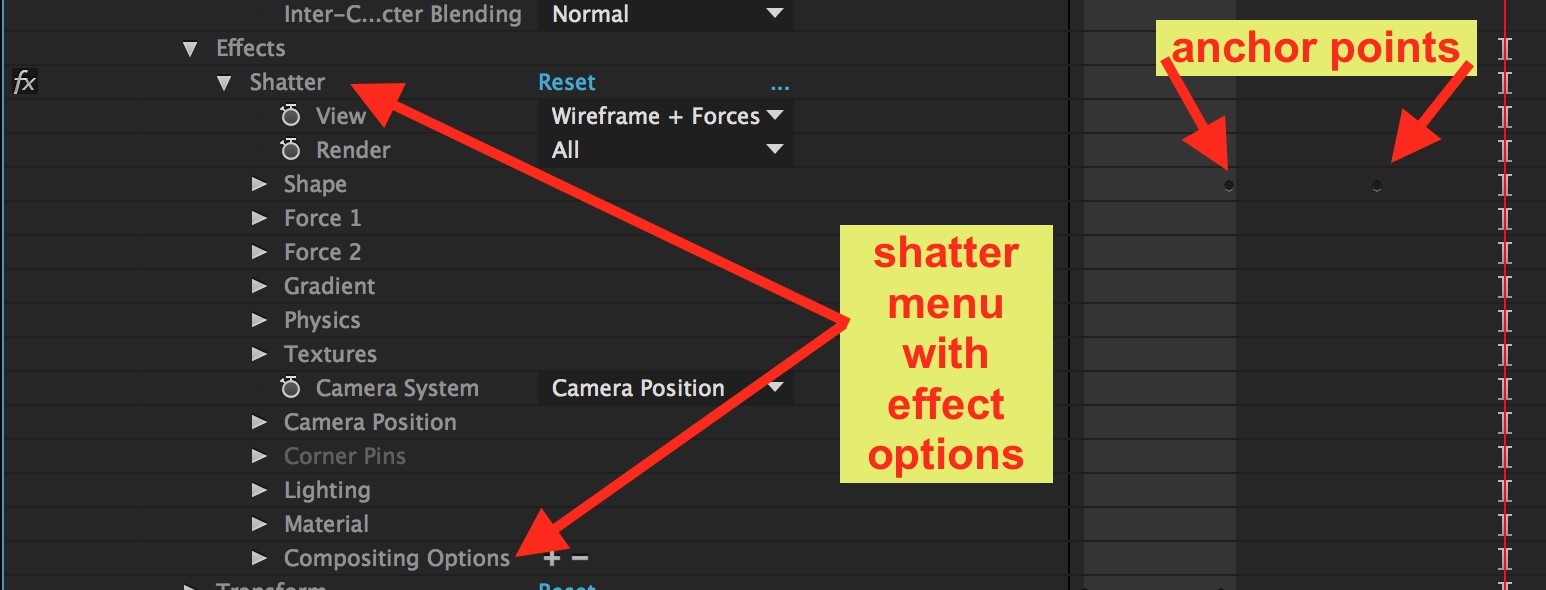

Adobe After Effects was used to make an animated title for the beginning of the video. This title included animated text, an animated image, and a glass shattering effect. To animate the text, the vertical and horizontal positions of the text boxes were changed at different points in the title and anchor points were added on the timeline, thus enabling Adobe After Effects to record the text’s different positions. The text was then rotated, with anchor points being added at each rotation value. This resulted in text that flew in from the left, right, top, and bottom, and rotated to fit properly on the screen. To make it look like a dinosaur was charging at the screen and shattering it, the media specialist placed a dinosaur image on the timeline and moved the dinosaur from off-screen to on-screen while adjusting the image’s scale. Anchor points were used to record the different positions to animate the image (see Figure 13).

Figure 13. Screenshot of Adobe After Effects anchor points, and position, scale, and rotation tools (Adobe After Effects CC 2015, Version 13.5.0.347).

Finally, a shatter simulation effect was applied. Once the effect was selected, the media specialist added anchor points to the timeline which the software recorded as the start and stop points of the shatter effect (see Figure 14).

Figure 14. Screenshot of Adobe After Effects anchor points, and position, scale, and rotation tools (Adobe After Effects CC 2015, Version 13.5.0.347).

The video and title were combined, and the final product was rendered and uploaded to Panopto for hosting. The completed product was placed on the Info-Matic Blog.

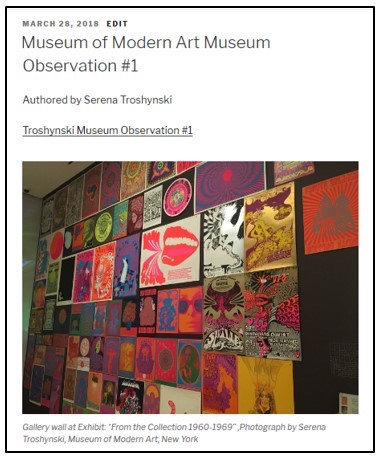

Upon completion of this assignment, students were required to upload their artifacts to the corresponding student benchmark page within the Info-Matic blog, in the section titled Access: Museum Data Management. Figure 15 provides a student assignment example demonstrating how the Museum of Modern Art incorporates technology into their exhibits to make better connections with their museum visitors.

Figure 15. Museum informatics access technology assignment example, by Serena Troshynski (http://info-matic.org/category/access-museum-data-management/).

Incorporating the Legal Benchmark-in-Action

To illustrate the Legal Benchmark-in-Action, a third site visit was held. During this visit the faculty member and students had a conversation with Jackie Swift, Repatriation Manager, and Michael Pahn, Head Archivist, from the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) in Washington, DC. The focus of this discussion was how the NMAI deals with ethical, political, and legal issues. Museum staff were provided with the benchmark as well as some guidance on the topics to discuss; however, they were not required to use a script. Topics discussed by the NMAI staff included the museum’s repatriation process and its policies to protect the human rights of native individuals.

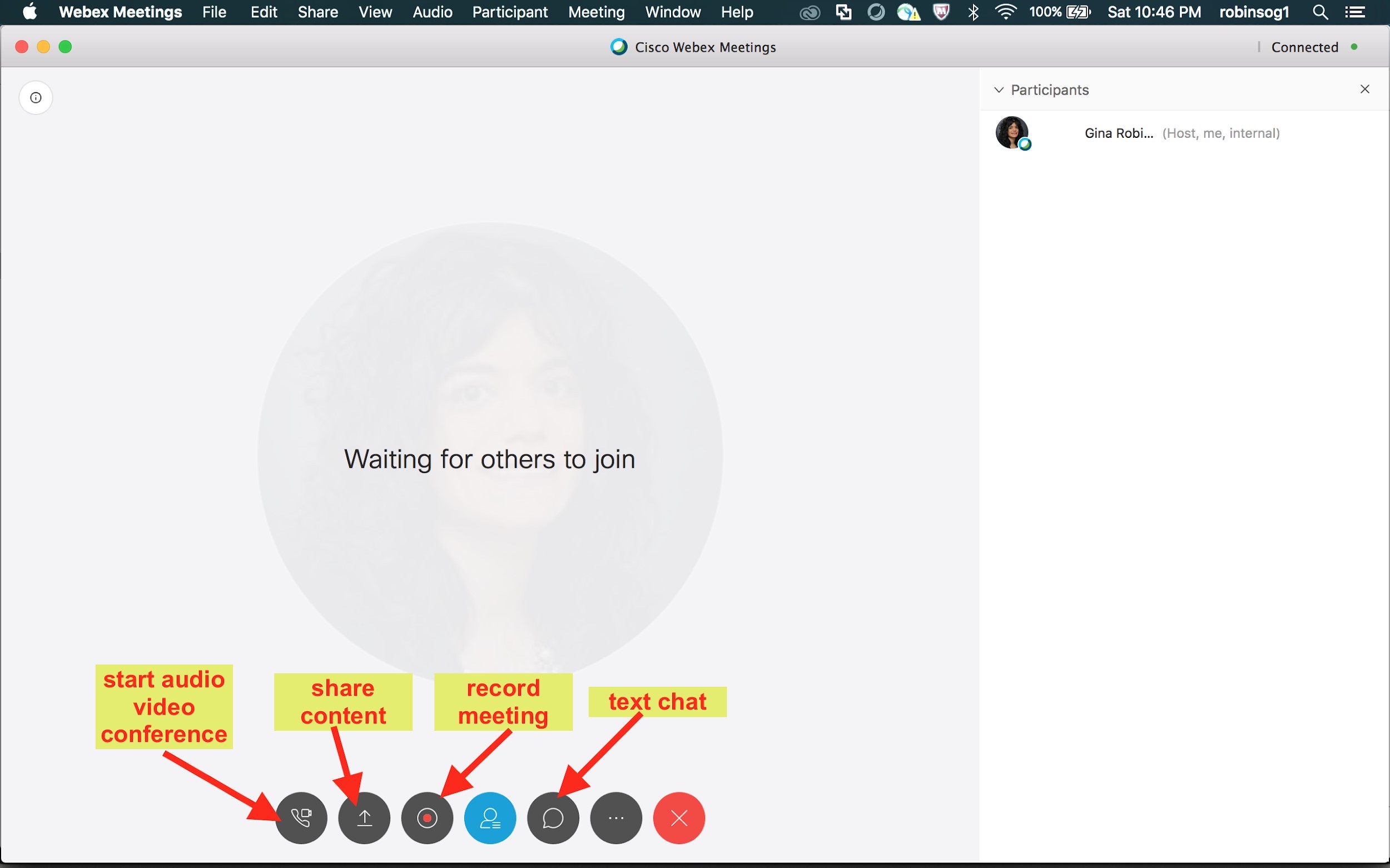

The main barrier the faculty member and media specialist faced with regard to this site visit was geographical distance. This museum is located in Washington, DC, whereas St. John’s University is located in New York. To resolve the issue of a four-hour driving distance, instead of visiting the museum physically, the faculty member and media specialist held a virtual meeting with two of the museum curators using Webex (Cisco Webex Meetings, Version 33.8.2.7), an online meeting program to which the university subscribes and provides access for all students and employees. This software enables users to hold synchronous meetings, classes, and presentations, and includes features such as video and audio conferencing, text chatting, content sharing, and the option to record meetings (see Figure 16).

Figure 16. Screenshot of Webex interface (Cisco Webex Meetings, Version 33.8.2.7).

Students were informed when the synchronous meeting was being held and had the option of joining in during the session or watching the recorded session at a later date. Students who participated in real-time were able to ask questions by speaking into a microphone or typing their questions into the chatbox. One of the DLIS graduate students was tasked with being the “voice of the chat,” with responsibilities that included monitoring the participant list and text chat for questions and participant alerts. The video conferencing portion of the Webex session was extracted and uploaded to Panopto and then placed on the Museum Info-Matic blog. Students then used this real-world example to demonstrate how their museum partner provides data security. An example is available on the Info-Matic blog under the student blog section titled Legal Issues in Museum Informatics (Figure 17).

Figure 17. Example of assignment on legal issues in museum informatics technology, by Laura Dellova (http://info-matic.org/category/legal-issues-in-museum-informatics/).

Incorporating the Social Media Benchmark-in-Action

To demonstrate the Social Media Benchmark-in-Action, the faculty member and media specialist organized a field trip to the Brooklyn Museum for the fourth site visit. The purpose of this visit was to explore how the Brooklyn Museum uses social media to reach visitors, both online and on-site. This is accomplished through the museum’s award-winning Ask app (https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/ask). The Ask app allows museum visitors to ask questions about exhibits that they are visiting. These questions are answered by members of the Audience Engagement team at the Brooklyn Museum. Elizabeth Treptow, a member of this team, described it as “a team of experts, educators, art historians who are ready for your questions, are ready to chat with you about art” (personal communication, April 18, 2017, https://bit.ly/2TW8gBW). A tour was provided by Elizabeth Treptow, and interviews were conducted with the Ask app team as well as students who were able to attend the trip in person. The museum personnel who were interviewed were given information about the social media benchmark as well as the purpose of the visit; however, they were not given a script to follow. The final result of the filming and editing of the tours and interviews was a comprehensive video about social media usage at the Brooklyn Museum. Content included a demonstration of how the app works with a specific exhibit, a behind-the-scenes look at the way questions are answered via the app, a presentation of the wiki that the app team uses to aggregate information about the exhibits, and students’ reflections about their experiences interacting with the app and meeting Brooklyn Museum staff.

The major barrier faced when filming at the Brooklyn Museum was poor audio quality, particularly in clips that were filmed within the large open areas of the museum. These included the presentation by Elizabeth Treptow, filmed in the Infinite Blue Exhibit area, and the student reflections, filmed in the museum lobby. Since we were unable to visit the museum after hours, we had to do our filming during regular visiting hours; therefore, there was a lot of chatter in the background of the videos.

The media specialist used Adobe Audition to reduce the background noise and increase the foreground noise, as in the audio edits done for the AMNH video. After completing this process, the media specialist decided to ask for a lapel microphone for future filming. Lapel microphones clip on to a speaker’s clothing and can be placed close to the mouth, improving sound focus and quality. This request was accepted and an Omnidirectional Condenser Lavalier Microphone from Audio-Technica (ATR3350iS) was purchased for future film sessions.

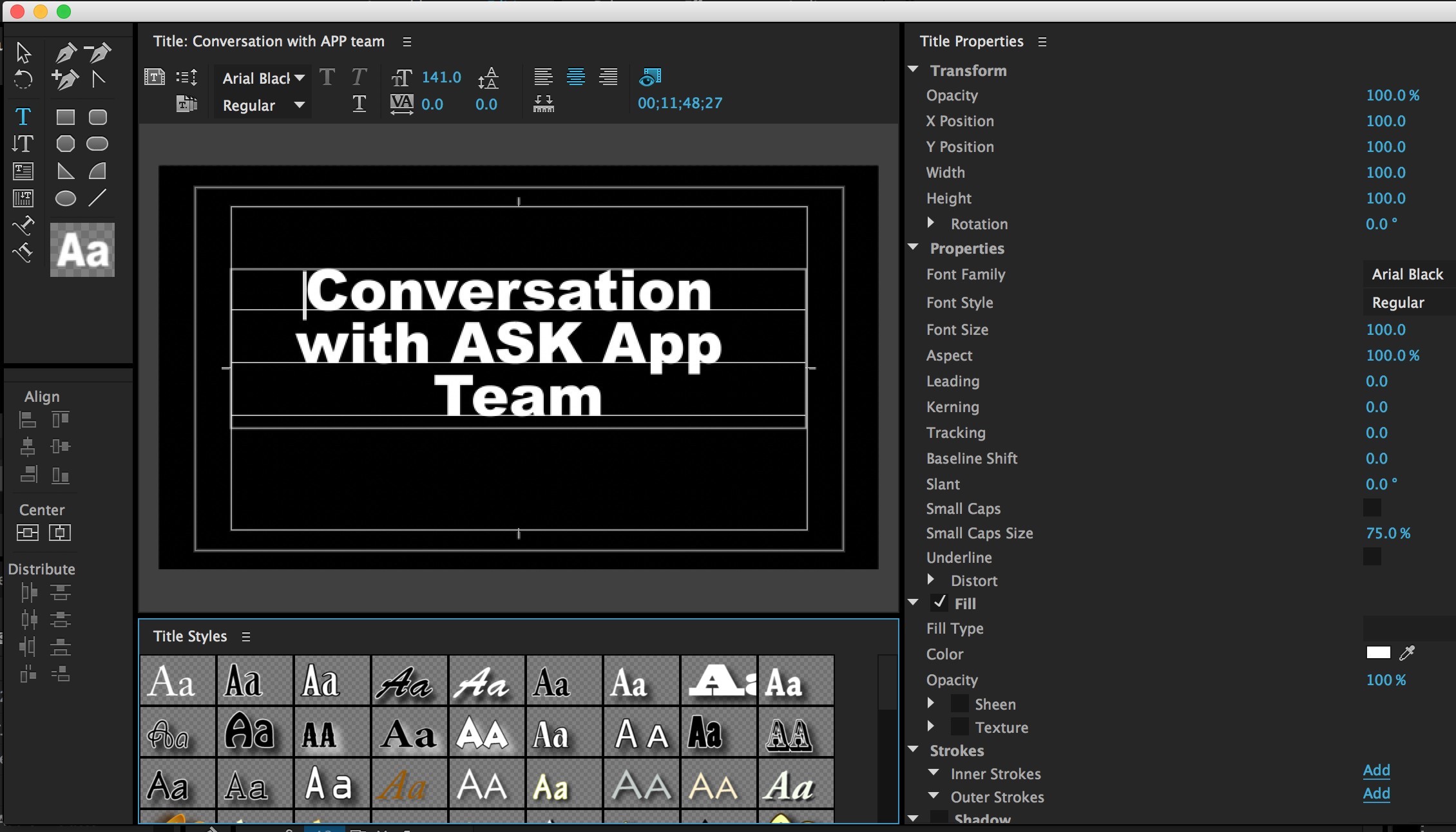

After editing the audio in the clips filmed in the open areas of the museum, the media specialist reviewed the clips filmed in the app team’s office. These clips did not require any editing with regard to background noise. Finally, after editing all the footage in both settings, the media specialist and the faculty member reviewed it to determine what to keep and what to discard. To remove excess footage the Razor Tool in Adobe Premiere Pro was used, and transitions were applied to combine the remaining footage into a cohesive video. Using the Title tool in Adobe Premiere Pro, the media specialist placed text between and on top of video clips when appropriate (see Figure 18).

Figure 18. Screenshot of Adobe Premiere Pro Title tool (Adobe Premiere Pro CC 2015, Version 9.0, Build 9.0.0 [247]).

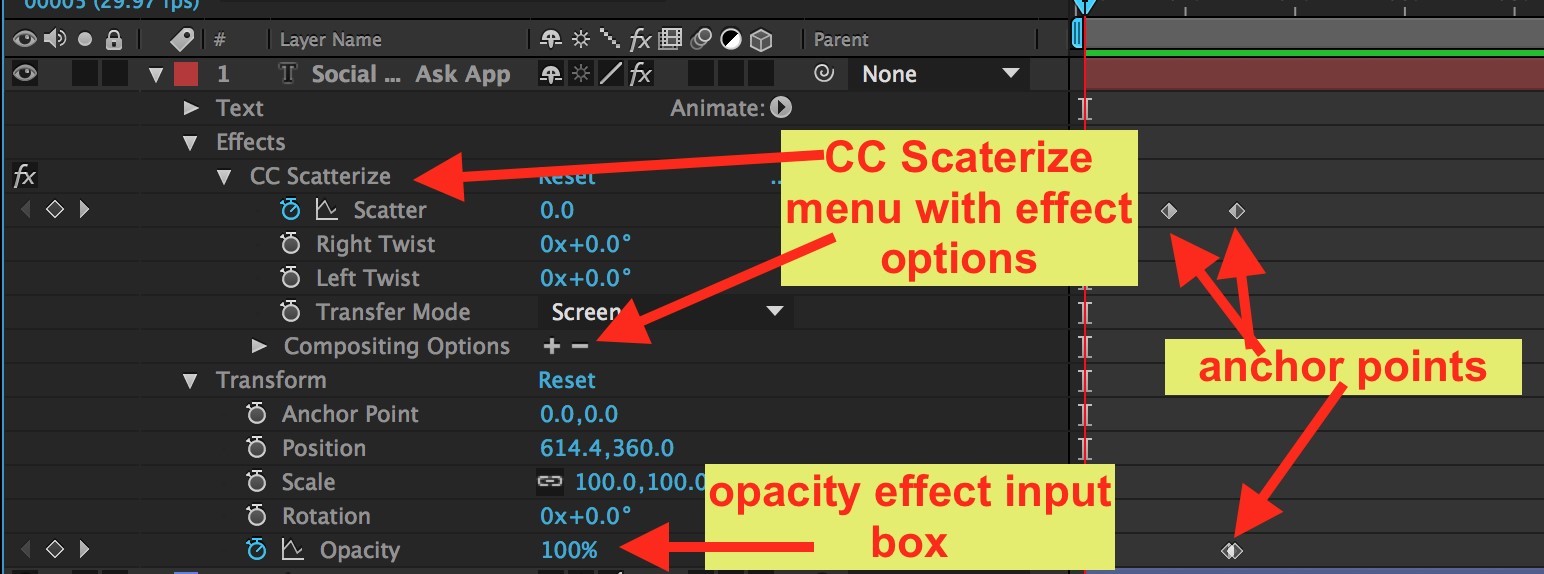

To design an animated title for the beginning of the video, the media specialist used Adobe After Effects. This title included text that faded into images of the museum exhibits. The CC Scatterize effect (Adobe, 2019d) was applied to the text, and the opacity of the text was reduced as it faded into the images (see Figure 19).

Figure 19. Screenshot of Adobe After Effects anchor points, and the CC Scatterize and Opacity tools (Adobe After Effects CC 2015, Version 13.5.0.347).

Last, after the title and video were combined and the finished product was rendered, the video was uploaded to Panopto for hosting and placed on the Info-Matic Blog.

Students were then able to use this as a real-world example of how information professionals implement social media technologies into their own collections as a means to connect to their museum visitors. Figure 20 presents an example of a student assignment on how the Jewish Museum incorporated social media technologies into its exhibits.

Figure 20. Museum informatics social media usage technology assignment example, by Lalaine Mercado (http://info-matic.org/category/social-media-usage/).

Student Experiences and Feedback

Assessing student learning was an important part of the museum informatics course. This was done through post-reflection letters that students wrote to themselves. In these letters, students discussed what they had learned throughout the semester and considered how this knowledge will be helpful when they become museum information professionals. Emphasis was placed on the course learning objectives, and in their letters, students provided specific examples of assignments that helped them meet these objectives. For example, with respect to the first objective, “to equip museum information professionals with the basic concepts and terminology of museum informatics” (Angel, 2019b, p. 3), one student, Dylan Hammond, discussed the Comparative Analysis of Information Management Assignment. This assignment required students to examine different content management systems and assess whether each one would be useful to their partner museum. According to Hammond, one takeaway from this assignment was the knowledge gained with respect to the importance of content management systems and the ability to recognize the differences between systems. This information was relayed to Hammond’s partner museum as feedback (Hammond, 2018, p. 4).

Another student, Katie Kirwan, related the second objective—“to provide museum information professionals with the skill set necessary to critically analyze and assess the impact of information science and technology on museums”—to an exhibit at the Bishop Museum. She applied the objective to the Holo Moana exhibit, which included an interactive wind exhibit. Kirwan was able to observe from this exhibit “how such technologies are an important means for educating visitors in a non-traditional way” (Kirwan, 2018, p. 3). The third objective—“to provide museum information professionals with an opportunity to explore the modern museum as an information environment, understanding such issues as intellectual property, copyright, and integrated collections management systems” (Angel, 2019b, p. 4)—was an important one for Christopher Anderson. By completing a copyright assignment that required students to obtain permission to display an object, Anderson was able to explore the intellectual property issues that information professionals must deal with (Anderson, 2018, p. 5).

In conclusion, the challenges faced by the faculty member in reconstructing a course originally designed for the face-to-face environment for use in an online learning environment were overcome with the support of a media specialist and by using digital media. Moreover, the partnership of the faculty member and the media specialist that evolved as they created the Benchmarks-in-Action for the restructured online course was invaluable in fostering a high-quality and engaging student–student and student–teacher presence within the online learning environment.

Keywords

Access – The use of technology by museum information professionals to increase the availability of their collections/artifacts/objects to museum visitors, both on-site and online.

Accreditation – Assessment of an educational program by an external agency to determine whether students are learning what the college or department intends them to learn, as determined by the core competencies, learning goals, and assignments outlined in the course syllabus.

Benchmark-in-Action – The creation of digital media to show how each block of study is used in a museum setting.

Demonstrated student achievement – Assessments created in a classroom environment that are used to determine whether students have achieved the learning goals and objectives as stated in the assignment instructions, the course material, and the course syllabus.

Informatics – The intersection of people, information, and technology within an environment.

Interactive – Technologies and professional practices within a museum that enable visitors to engage with collections and artifacts within the online and face-to-face environments.

Legal issues – Data/information security and privacy within the museum environment, both online and on-site.

Social media – Tools that enable a museum visitor, on-site or online, to connect with museum collections, objects, and exhibits, thereby allowing the visitor, student or otherwise, increased interactivity with the museum objects via the inclusion of their voice in the application of key terms and descriptions to the objects within the museum environment.

Technology – Tools implemented by a museum information professional that enhance museum patrons’ engagement, both on-site and online.

References

Adobe. (2019a). After Effects: User manual. Retrieved from https://helpx.adobe.com/after-effects/user-guide.html

Adobe. (2019b). Audition: User manual. Retrieved from https://helpx.adobe.com/audition/user-guide.html

Adobe. (2019c). Photoshop: User manual. Retrieved from https://helpx.adobe.com/photoshop/user-guide.html

Adobe. (2019d). Premiere Pro: User manual. Retrieved from https://helpx.adobe.com/premiere-pro/user-guide.html

American Library Association. (2019). Directory of ALA-accredited programs in searchable database format. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/cfapps/lisdir/listing.cfm

American Library Association Council. (2009). ALA’s core competences of librarianship. American Library Association. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/educationcareers/sites/ala.org.educationcareers/files/content/careers/corecomp/corecompetences/finalcorecompstat09.pdf

American Library Association Council. (2019). Standards for accreditation of master’s programs in library and information studies. American Library Association. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/educationcareers/sites/ala.org.educationcareers/files/content/standards/Standards_2019_ALA_Council-adopted_01-28-2019.pdf

Anderson, A. (2018). Anderson post-reflection letter. Unpublished manuscript, St. John’s College, St. John’s University, Queens, New York.

Angel, C. (2016). Collaboration among faculty members and community partners: Increasing the quality of online library and information science graduate programs through academic service-learning. Journal of Library & Information Services in Distance Learning, 10(1–2), 4–14. doi:10.1080/1533290X.2016.12

Angel, C. (Ed.). (2019a). Info-Matic: A DLIS project. Retrieved from http://info-matic.org/

Angel, C. (2019b). LIS 258 Museum Informatics course syllabus. Unpublished manuscript, Division of Library and Information Science, St. John’s University, Queens, New York.

Ascher, S., & Pincus, E. (2013). The filmmaker’s handbook: A comprehensive guide for the digital age (4th ed.). Penguin Group, New York.

Audio-Technica. (2019). Omnidirectional Condenser Lavalier Microphone: User manual. Retrieved from https://www.audio-technica.com/cms/resource_library/literature/6c0d3d95d1d36a69/p52518_atr3350is_user_manual.pdf

Cisco. (2019). Webex Help Center. Retrieved from

https://help.webex.com/?language=en-us

Council for Higher Education Accreditation. 2019. CHEA: Recognition policy and procedures. Retrieved from https://www.chea.org/sites/default/files/pdf/Recognition-Polic-FINAL-Dec-2018.pdf

Costley, J., & Lange, C. H. (2017). Video lectures in e-learning. Interactive Technology and Smart Education, 14(1), 14–30. doi:http://dx.doi.org.jerome.stjohns.edu:81/10.1108/ITSE-08-2016-0025

Croft, N., Dalton, A., & Grant, M. (2010). Overcoming isolation in distance learning: Building a learning community through time and space. Journal for Education in the Built Environment, 5(1), 27–46. doi:10.11120/jebe.2010.05010027

Dolan, J., Kain, K., Reilly, J., & Bansal, G. (2017). How do you build community and foster engagement in online courses? New Directions for Teaching & Learning, 2017(151), 45–60. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.20248

Draus, P. J., Curran, M. J., & Trempus, M. S. (2014). The influence of instructor-generated video content on student satisfaction with and engagement in asynchronous online classes. Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 10(2), 240–254. Retrieved from https://search-proquestcom.jerome.stjohns.edu/docview/1614680247/8CED0B6EC14A44A4PQ/6?accountid=14068

Dublin Core Metadata Initiative. (2019). Creating metadata. Retrieved from http://www.dublincore.org/resources/userguide/creating_metadata/

Hammond, D. (2018). Post-reflection letter. Unpublished manuscript, St. John’s College, St. John’s University, Queens, New York.

Improve Photography, LLC. (2017). Photography basics 101: Aperture, shutter speed, and ISO [online forum]. Retrieved from https://improvephotography.com/photography-basics/aperture-shutter-speed-and-iso/

Iyer, H. (2007). “Core competencies for visual resources management.” Retrieved from http://vraweb.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/iyer_core_competencies.pdf

Kirwan, K. (2018). Post-reflection letter. Unpublished manuscript, St. John’s College, St. John’s University, Queens, New York.

Lehman, R. M., & Conceição, S. C. O. (2010). Creating a sense of presence in online teaching: How to “be there” for distance learners (1st ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Marty, P. F. (2008). An introduction to museum informatics. In P. F. Marty & K. B. Jones (Eds.), Museum informatics: People, information, and technology in museums (pp. 3–8). New York, NY: Taylor & Francis.

Marty, P. F. (2010). Museum informatics. In M. J. Bates & M. N. Maack (Eds.), Encyclopedia of library and information sciences (3rd ed., pp. 3717–3725). Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis. doi:https://doi.org/10.1081/E-ELIS3

Merritt, E. E. (Ed.). (2008). National standards and best practices for U.S. museums (Reprint edition). Washington, DC: American Alliance of Museums.

Panopto (Version 5.8.0 [5.8.0.37552]) [Computer software]. (2020). Retrieved from https://support.panopto.com/s/article/Panopto-5-8-Release-Notes

Sherer, P., & Shea, T. (2011). Using online video to support student learning and engagement. College Teaching, 59(2), 56–59. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/87567555.2010.511313

Stafford, K., Portis, M., Andres, A., & Henri, J. (2017). ARLIS/NA core competencies for art information professionals. Retrieved from the Art Libraries Society of North America Website: https://www.arlisna.org/images/researchreports/arlisnacorecomps.pdf

Tuthill, G., & Klemm, E. B. (2002). Virtual field trips: Alternatives to actual field trips. International Journal of Instructional Media, 29(4), 453–468. Retrieved from https://jerome.stjohns.edu:81/login?url= ?url=https://search-proquest-com.jerome.stjohns.edu/docview/204317859?accountid=14068

Visual Resources Association. (2018). Retrieved from http://vraweb.org/

WordPress (Version 5.1) [Computer Software]. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://wordpress.org/news/2019/02/betty/

Zoom. (2007). Handy Recorder H2: Operation manual. Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo: Zoom Corporation.

Zoom. (2019). H2. Retrieved from https://www.zoom-na.com/products/field-video-recording/field-recording/h2-handy-recorder