18

18.1 Introduction

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

- Understand how corporations are structured and managed.

- Learn about shareholder rights and the powers and liabilities of corporate officers and directors.

- Learn the legal theories under which limited liability is taken away from corporations.

- Comprehend how corporations merge, consolidate, and dissolve.

Corporations are incredibly important to the stability and growth of the US economy. Without corporations, industries such as pharmaceuticals and technology would not be able to raise the capital needed to fund their research and development of new drugs and products. As discussed in Chapter 16, corporations are incorporated under state law and are subject to double taxation. Corporations are separate legal entities from the shareholders who own them.

18.2 Corporate Structure

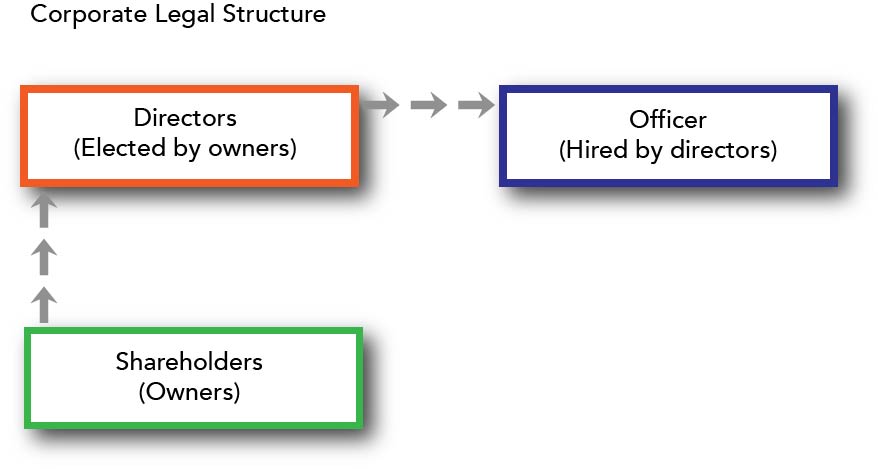

Under most state laws, corporations are required to have at least one director. A director is a person appointed or elected to sit on a board that manages the business of a corporation and supervises its officers. Directors are elected by shareholders and collectively are called the Board of Directors. Directors elect officers, who are responsible for the daily operations of the corporation. Officers often have titles such as president, chief operating officer, chief financial officer, or controller.

Figure 18.1 Corporate Legal Structure

18.3 Shareholder Rights

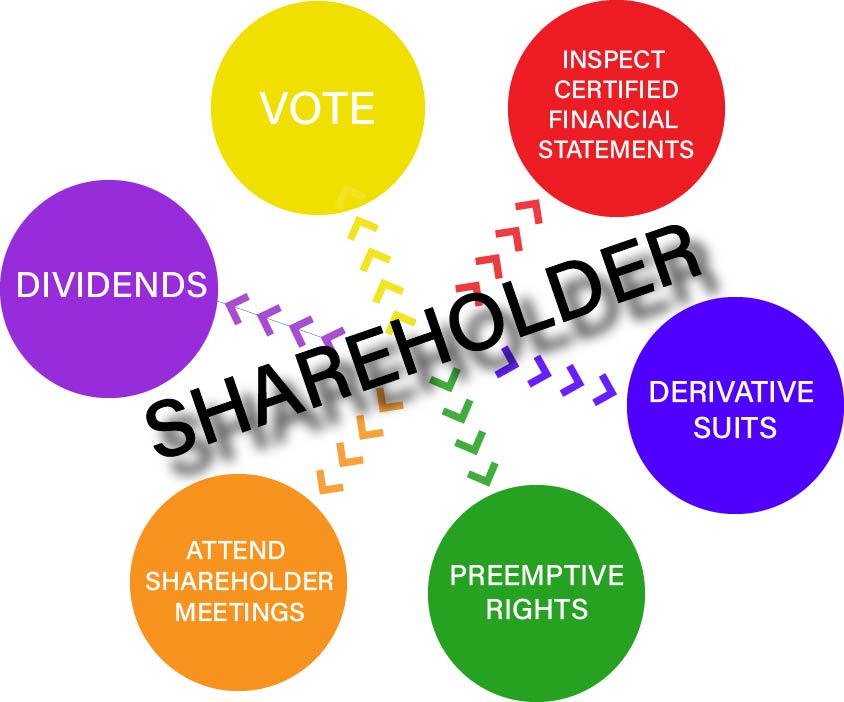

As owners of the corporation, shareholders have specific rights to help them assess their investment decisions. Shareholders are not entitled to manage the day-to-day operations of the business, but they enjoy the following rights.

Figure 18.2 Corporate Shareholder Rights

Inspection

Shareholders have the right to inspect the certified financial records of a corporation. This right also extends to other information related to exercising their voting privilege and making investment decisions.

The right, however, is limited to good-faith inspections for proper purposes at an appropriate time and place. A proper purpose is one that seeks to protect the interests of both the corporation and the shareholder seeking the information. In other words, the inspection cannot be against the best interest of the corporation.

Courts have held that proper purposes include:

- Reasons for lack of dividend payments or low dividend amounts;

- Suspicion of mismanagement of assets or dividends; and

- Holding management accountable.

Corporations have a legitimate interest in keeping their financial and managerial documents private. Therefore, inspection of documents usually occurs at the corporation’s headquarters during regular business hours. Documents made available for inspection do not have to be allowed off premise if the corporation does not want them to be removed.

Shareholder Meetings

Shareholders have the right to notice and to attend shareholder meetings. Shareholder meetings must occur at least annually, and special meetings may be called to discuss important issues such as mergers, consolidations, change in bylaws, and sale of significant assets. Failure to give proper notice invalidates the action taken at the meeting.

A quorum of shareholders must be present at the meeting to conduct business. A quorum is the minimum number of shareholders (usually a majority) who must be present to take a vote. The corporation’s bylaws define what constitutes a quorum, if not set by state law.

If a shareholder is not able to be physically present during a meeting, he or she may vote by proxy. A proxy is a person authorized to vote on another’s stock shares.

Vote

Depending on the type of share owned, shareholders may have the right to vote. In general, shareholders of common stock are entitled to a vote for each share of stock owned. Owners of preferred stock often do not have a voting right in exchange for a higher dividend amount or preference in receiving dividends.

Common issues that shareholders vote on include:

- Election of directors;

- Mergers, consolidations, and dissolutions;

- Change of bylaws;

- Change in major corporate policies; and

- Sale of major assets.

Preemptive Rights

The Preemptive right is a shareholder’s privilege to buy newly issued stock in the corporation before the shares are offered to the public. Shareholders are allowed to buy shares in an amount proportionate to their current holdings to prevent dilution of the existing ownership interests.

Preemptive rights usually must be exercised within thirty to sixty days of being offered. This allows the corporation to complete the sale to shareholders before offering any remaining shares to the public.

Derivative Suit

A derivative suit is a lawsuit brought by a shareholder on the corporation’s behalf against a third party because of the corporation’s failure to take action on its own. Derivative actions are usually brought by shareholders against officers or directors for not acting in the best interest of the corporation.

To be eligible to bring a derivative action, a shareholder must own shares in the corporation at the time of the alleged injury. An individual or business cannot buy shares in a corporation to file a derivative suit for actions that occurred before becoming a shareholder.

Before bringing a derivative suit, shareholders must show that they attempted to get the officers and directors to act on behalf of the corporation first. Only after the officers and directors refuse to act may a derivative suit be filed.

Dissatisfaction with the corporation’s management is insufficient to justify a derivative suit. Derivative suits have been successful when misconduct or fraud of a director or officer is involved. If successful, any damages are awarded to the corporation, not the shareholders who brought the lawsuit.

Dividends

A dividend is a portion of a corporation’s profits distributed to its shareholders on a pro rata basis. Dividends are usually paid in the form of cash or additional shares in the corporation.

Although shareholders have a right to a dividend when declared, the board of directors has the discretion to decide whether to declare a dividend. The board may decide to reinvest profits into the corporation, pay for a capital expense, purchase additional assets, or to expand the business. As long as the board of directors acts reasonably and in good faith, its decision regarding whether to declare a dividend is usually upheld by the courts.

18.4 Corporate Officer and Directors

Although shareholders own the corporation, the officers and directors are empowered to manage the day-to-day business of the corporation. The officers and directors owe a fiduciary duty to both the corporation and its shareholders. This means that the officers and directors must act in the best interest of the corporation and shareholders.

Duty of Loyalty

As part of their fiduciary duty, officers and directors have a duty of loyalty to the corporation and its shareholders. The duty of loyalty requires them to act:

- In good faith;

- For a lawful purpose;

- Without a conflict of interest; and

- To advance the best interests of the corporation.

Duty of loyalty issues frequently arise in the context of a director entering into a contract with the corporation or loaning it money. Other situations may involve a director taking a business opportunity away from the corporation for his or her own personal gain. The corporate opportunity doctrine prevents officers and directors from taking personal advantage of a business opportunity that properly belongs to the corporation.

Duty of Care

The duty of care requires officers and directors to act with the care that an ordinary prudent person would take in a similar situation. In other words, they have a duty not to be negligent.

The extent of this duty depends on the nature of the corporation and the type of role the director or officer fills. For example, the duty of care imposed on the board of directors of a federally-insured bank will be higher than the duty imposed on a small nonprofit organization.

In general, though, directors should understand the nature and scope of the corporation’s business and industry, as well as have any particular skills necessary to be successful in their role. Officers and directors also should stay informed about the corporation’s activities and hire experts when they lack the expertise necessary to make the best decisions for the corporation. The duty of care requires officers and directors to make informed decisions.

Compensation

Officers and directors are usually entitled to compensation for their work on behalf of the corporation. Some states restrict whether directors may receive compensation and, if so, how much. The issue of executive compensation has been a hot button issue in recent decades.

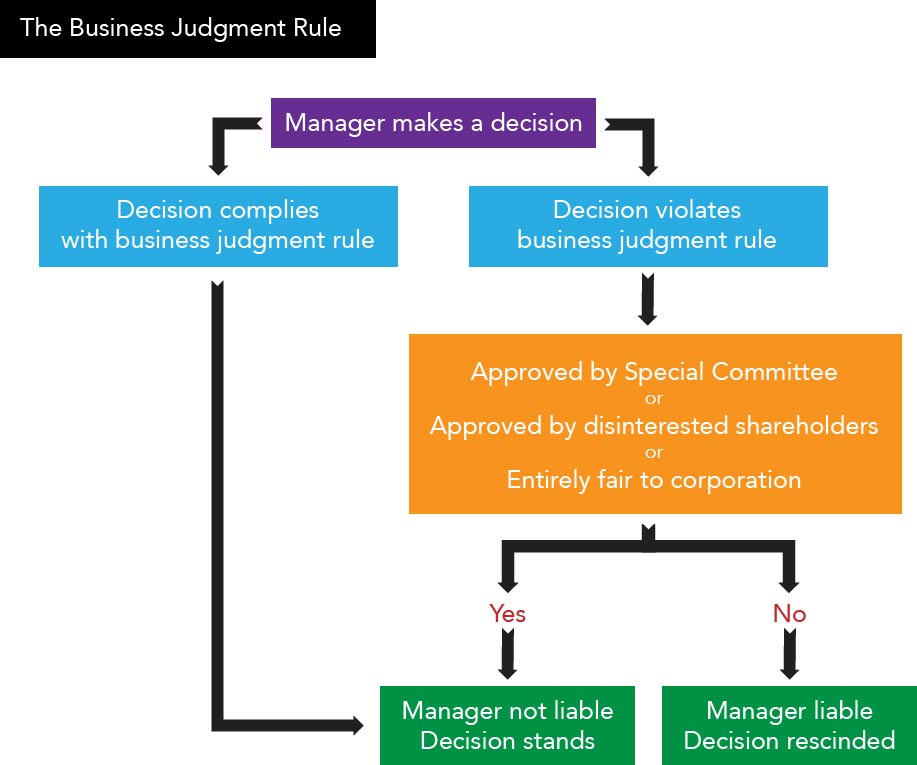

Business Judgment Rule

The business judgment rule is the presumption that corporate directors act in good faith, are well-informed, and honestly believe their actions are in the corporation’s best interest. The rule shields directors and officers from liability for unsuccessful or unprofitable decisions, as long as they were made in good faith, with due care, and within their authority.

It is important to understand that courts do not focus on the result of the business decision. Instead, courts look at the process that the decision makers went through. If the process is careless or not in the best interest of the corporation and shareholders, the business judgment rule will not protect them.

The business judgment rule does not protect officers and directors from decisions made in their own self-interest or self-dealing. In those situations, the action must be approved by disinterested members of the board of directors or shareholders. If the decision is subject to a derivative suit, the court may determine that the decision was fair to the corporation. If the decision is approved by the court or disinterested board members or shareholders, then the decision may be valid.

The business judgment rule does not protect officers and directors from decisions made in bad faith, as a result of fraud, through gross negligence, or as an abuse of discretion. In those situations, the officers and directors may be personally liable for their actions.

Figure 18.3 Business Judgment Rule Flowchart

18.5 Legal Theories

One of the main benefits of corporations is limiting shareholders’ liability to the amount of their investment in the corporation. In general, a shareholder may lose his or her investment in the corporation if it is not a successful business or if it is sued. Because corporations are a separate legal entity than their shareholders, shareholders are generally shielded from corporate liability. However, three exceptions to this rule allow shareholders to be held liable for the corporation’s actions.

Piercing the Corporate Veil

Piercing the Corporate Veil is a legal theory under which shareholders or the parent company are held liable for the corporation’s actions or debts. Under this theory, plaintiffs ask the court to look beyond the corporate structure and allow them to sue the shareholders or parent company as if no corporation existed. In essence, the court strips the “veil” of limited liability that incorporation provides and hold a corporation’s shareholders or directors personally liable.

This theory applies most often in closely held corporations. While legal requirements vary by state, courts are usually reluctant to pierce the corporate veil. However, courts will do so in cases involving serious misconduct, fraud, commingling of personal and corporate funds, and deliberate undercapitalization during incorporation.

Alter Ego Theory

The Alter Ego Theory is the doctrine that shareholders will be treated as the owners of a corporation’s property or as the real parties in interest when necessary to prevent fraud or to do justice. In other words, the court finds a corporation lacks a separate identity from an individual or corporate shareholder.

This theory applies most often when a corporation is a wholly-owned subsidiary of another company. Courts allow the alter ego theory when evidence exists that the parent company is controlling the actions of the subsidiary, and the corporate form is disregarded by the shareholders themselves. The rationale is that shareholders cannot benefit from limited liability when there is such unity of ownership and interest that a separate entity does not actually exist. To allow shareholders to “have it both ways” would result in injustice to the corporation’s debtors and those hurt by its actions.

Promotion of Justice Theory

The Promotion of Justice Theory is used when the corporate form is used to defraud shareholders or to avoid compliance with the law. Courts use this theory to prevent shareholders from using a corporation to achieve what they could not do directly themselves. For example, if a state limits the number of liquor licenses an individual may obtain at one time, a person cannot form multiple corporations to obtain more licenses.

18.6 Mergers, Consolidations, and Dissolutions

Once incorporated, corporations may last forever. However, they also may be merged or consolidated into other business entities or dissolved.

Often businesses will buy the assets of another business. When this happens, the seller remains in existence and retains its liabilities. The buyer does not become legally responsible for the seller’s actions through a mere purchase of assets.

Mergers and consolidations, however, involve the termination of the seller.

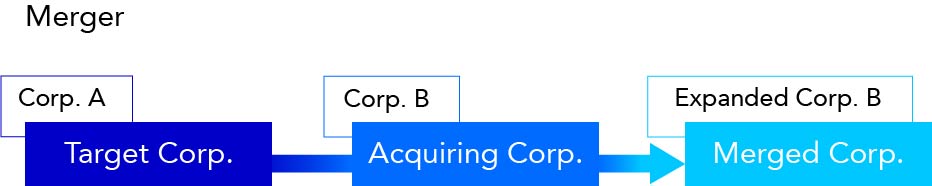

Merger

A merger occurs when one corporation absorbs another. The acquiring corporation continues to exist but the target corporation ceases to exist. The acquiring corporation acquires all the assets and liabilities of the target corporation.

Corporate mergers must conform to state laws and usually must be approved by the majority of shareholders of both corporations. Many states require approval by two-thirds of the shareholders. If approved, articles of merger must be filed in the state(s) where the corporations exist.

Figure 18.4 Merger

Consolidation

Consolidation occurs when two or more corporations are dissolved and a new corporation is created. The new corporation owns all the assets and liabilities of the former corporations.

Like mergers, consolidations must be approved by the majority or two-thirds of shareholders of all corporations involved. If approved, articles of consolidation must be filed in the state(s) where the corporations existed.

Mergers and consolidations are often scrutinized under antitrust laws to ensure that the resulting corporation is not a monopoly in the relevant market. Antitrust laws are discussed in Chapter 19.

Figure 18.5 Consolidation

Voluntary Dissolution

A corporation that has obtained its charter but has not begun its business may be dissolved voluntarily by its incorporators. They simply need to file articles of dissolution in the state of incorporation.

If a corporation has been in business, voluntary dissolution is possible when either (1) all shareholders give written consent or (2) the board of directors vote for dissolution and two-thirds of the shareholders approve.

To dissolve a corporation voluntarily, the corporation must file a statement of intent to dissolve. At that point, the corporation must cease all business operations except those necessary to wind up its business affairs. The corporation must give notice to all known creditors of its dissolution. If the corporation fails to give notice, then the directors become personally responsible for any debt and legal liability. The corporation is required to pay off all debts before distributing any remaining assets to shareholders.

Until the state issues the articles of dissolution, the statement of intent may be revoked if shareholders change their mind.

Involuntary Dissolution

States have the power to create corporations through granting corporate charters. Similarly, states have the right to revoke corporate charters. Actions brought by the state to cancel a corporate charter are called quo warranto proceedings.

Corporate charters may be canceled when a corporation:

- Did not file its annual report;

- Failed to pay its taxes and licensing fees;

- Obtained its charter through fraud;

- Abused or misused its authority;

- Failed to appoint or maintain a registered agent; or

- Ceased to do business for a certain period of time.

Shareholders may also request dissolution when:

- The shareholders are deadlocked and cannot elect a board of directors;

- When there is illegal, fraudulent or oppressive conduct by the directors or officers;

- When majority shareholders breach their fiduciary duty to the minority shareholders;

- Corporate assets are being wasted or looted; or

- The corporation is unable to carry out its purpose.

Finally, dissolution may occur as a result of bankruptcy or when the corporation is unable to cover its debts to creditors.

18.7 Concluding Thoughts

Corporations are owned by shareholders but are run by directors and officers. As a legal entity separate from its shareholders, corporations provide limited liability to shareholders who invest in them. However, personal liability may be imposed when fraud or other serious misconduct occurs. As long as their decisions are made in good faith, with due care, and within their authority, officers and directors are protected by the business judgment rule. Finally, corporations have a perpetual existence unless they are dissolved through their own action, by the state, or initiated by shareholders or creditors.