19

19.1 Introduction

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

- Understand the important federal antitrust laws, along with their exemptions.

- Learn the factors used to determine whether a monopoly exists.

- Comprehend the common types of unreasonable restraints on trade.

Antitrust laws are designed to protect trade and commerce from unreasonable restraints, monopolies, price fixing, and price discrimination. Antitrust laws regulate the market just enough to foster economic growth and competition while preventing stagnation and unethical practices by monopolies that prevent the free market from operating as it should.

The main federal antitrust laws are the Sherman Act, the Clayton Act, and the Federal Trade Commission Act. The legislative declarations of these Acts make it clear that Congress wants to promote fair competition within the market economy.

19.2 Historical Development

The United States economy was founded on the capitalist principle of free enterprise. Free enterprise is a private and consensual system of production and distribution, usually conducted for profit in a competitive environment, that is relatively free of governmental interference. The theory is that, given the freedom, businesses will operate efficiently and be responsive to consumer needs and demands.

The weakness of the free enterprise system is that it assumes that businesses will be ethical and compete with each other fairly. During the Industrial Revolution, powerful businessmen took advantage of the free enterprise system to increase their wealth at the expense of their workers, competitors, and consumers.

These Industrialists bought shares in competing companies then transferred the shares to a trust. The trust then set prices for goods within the industry, determined which companies could operate in a given geographic area, and micromanaged the business operations of companies within an industry. As a result, companies that were not part of the trust went bankrupt, new competitors were prevented from entering the market, and consumer prices rose beyond market requirements.

States tried to stop the abuses of the Industrialists through the trusts. State attempts failed because the US economy was growing beyond state industries to national ones. As a result, national legislation was needed to restore balance to the market. The resulting legislation is called “antitrust law” because its purpose was to break up the power of the Industrialists’ trusts.

In 1890, Congress passed the Sherman Antitrust Act under its power to regulate interstate commerce. The Sherman Antitrust Act (also known as the Sherman Act) prohibits direct or indirect interference with the freely competitive interstate production and distribution of goods. The Act addresses two main concerns:

- Unreasonable restraints on trade between two or more parties; and

- Monopolies.

In 1914, Congress passed the Clayton Act. The Clayton Act amended the Sherman Act and expanded antitrust regulations to prohibit:

- Price discrimination;

- Tying arrangements;

- Exclusive-dealing contracts; and

- Mergers resulting in monopolies or substantially lessening competition.

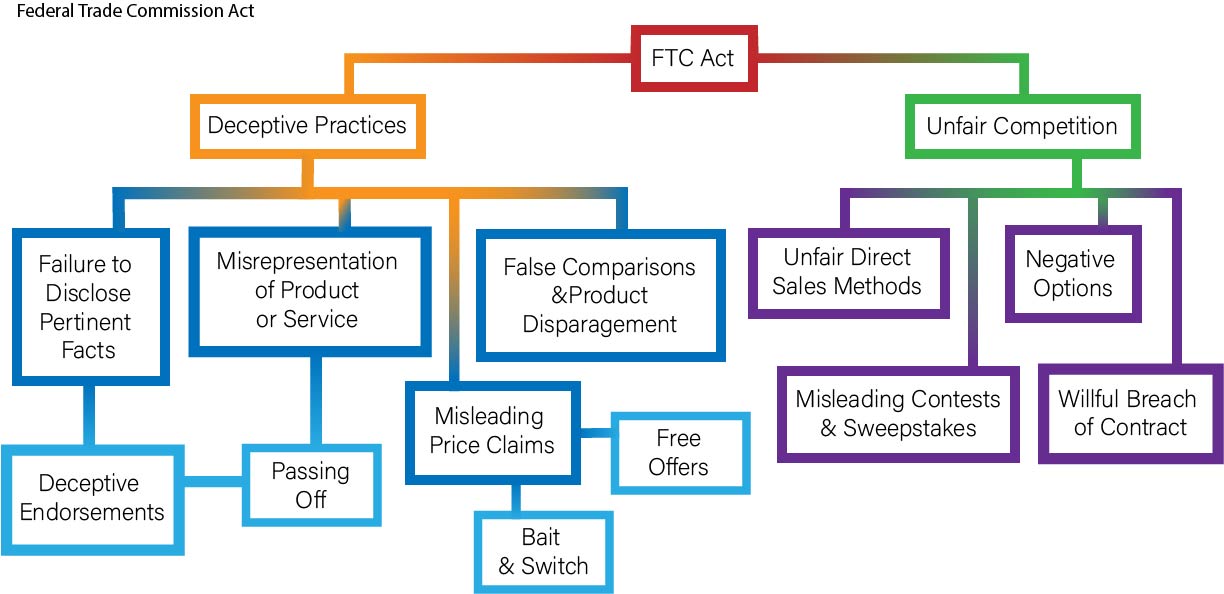

Congress also passed the Federal Trade Commission Act in 1914. The Federal Trade Commission Act established the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to protect consumers against deceptive practices and enforce antitrust laws. The Act prohibits false, deceptive, and unfair advertising and trade practices. Some of these practices are discussed in more detail in Chapter 20.

Figure 19.1 The Federal Trade Commission Act

The last major antitrust law is the Robinson-Patman Act, which was passed by Congress in 1936. The Robinson-Patman Act amended the Clayton Act and prohibits price discrimination that hinders competition or that tends to create a monopoly.

19.3 Monopoly

A monopoly is the control or advantage obtained by one supplier or producer over the commercial market within a given region. Not all monopolies are illegal. In fact, some industries are exempted from antitrust laws:

- Highly regulated industries;

- Utilities;

- Railroads;

- Airlines;

- Insurance companies;

- Securities; and

- Banks

- Labor unions;

- Agricultural and fishing cooperatives (farmers not distributors);

- Exporters;

- Lobbyists;

- States (unclear if includes US territories); and

- Professional baseball.

To be an illegal monopoly, a business must have (1) monopoly power (2) in the relevant market and (3) the intent to acquire and use such power.

Monopoly Power

Monopoly power is the power of a business to fix prices unilaterally or to exclude competition. The size of a business’s market share is a primary factor of whether monopoly power exists.

Courts have found monopoly power when a business controls seventy percent or more of a market.

If a business controls 51-69 percent of a market, then it is possible that monopoly power exists. Courts examine other factors such as number of competitors, market concentration, degree of difficulty for new businesses to enter the industry, and the nature of the industry. If the entry costs and barriers are high and there are few other competitors, a business may have monopoly power when it controls slightly more than half the market.

If a business controls fifty percent or less of a market, then no monopoly power exists.

Relevant Market

To determine whether a business has monopoly power, it must be determined whether it has monopoly power within the relevant market. However, defining the relevant market can be challenging. The relevant market includes both the product or service market and the geographic area.

Product or Service Market

The first element in determining the relevant market is to determine what goods or services are interchangeable in consumers’ minds. This is sometimes called substitutability or functional interchangeability. Defining the exact product or service market is usually heavily litigated because it may result in market concentration or dilution, and ultimately whether a business has enough market share to be deemed a monopoly.

For example, Ford shares the passenger truck market with manufacturers such as Chevrolet, GMC, Dodge, Toyota, Nissan, and Honda. However, Ford shares the commercial truck market with manufacturers such as Peterbilt, Volvo, Daimler, and Volkswagen. If sued for violation of antitrust law, Ford would want a broad definition of the product market, such as “trucks,” to include a greater number of competitors and lessen its own market share. Plaintiffs would want to define the product narrowly, such as “three-quarter ton passenger trucks,” to lessen the number of competitors and heighten Ford’s market share.

As large companies expand their products and services across industries, this inquiry becomes more complex and expensive to litigate.

Geographic Area

Determining a business’s market power also requires determining the geographic area in which the business operates. As globalization and e-commerce increase the geographic reach of businesses, this inquiry is also becoming more difficult.

For example, should the market for Ford passenger trucks be determined by city, state, nation, continent, hemisphere, or globally? Ford trucks may have higher sales in Detroit, Michigan than in Tokyo, Japan. Determining the geographic area of the relevant market may include areas of higher or lesser concentrations of sales. Therefore, parties also heavily litigate what is the appropriate geographic area for the relevant market.

Intent

The third factor is the business’s intent to acquire and use its monopoly power.

Not all monopolies are the result of a business’s predatory actions. Some “boom and bust” industries, such as mining and oil and gas, are difficult to maintain long-term success. If an industry goes through a difficult time and competitors go out of business, the remaining company may end up as a monopoly without engaging in anticompetitive behavior.

To determine intent, courts look at the conduct of the business. Purchasing smaller competitors to increase its market share and engaging in predatory pricing is often evidence of a company’s intent to become a monopoly.

Specifically, an intent to monopolize requires:

- Predatory or anticompetitive conduct;

- Specific intent to control prices or destroy competition; and

- A dangerous probability of success.

A business’s intent is evaluated in the context of the current industry and economic conditions. For example, are there significant changes to the law that affect the profitability of the industry or an economic downturn that impacts competition? Just because a company is large enough to successfully survive a challenging time, it may not have the necessary intent to become an illegal monopoly.

19.4 Unreasonable Restraints on Trade

Antitrust laws prohibit unreasonable restraints on trade. A restraint on trade is an agreement between two or more businesses intended to eliminate competition, create a monopoly, artificially raise prices, or adversely affect the free market. A restraint on trade that produces a significant anticompetitive effect and, therefore, violates antitrust laws is an unreasonable restraint on trade.

Concerted Action

Concerted action is an action that has been planned, arranged, and agreed on by parties acting together to further some scheme or cause. Concerted action can be either horizontal or vertical. Horizontal agreements occur between direct competitors. For example, cell phone providers decide to lock customers into two-year contracts. Customers are required to agree to terms that benefit the companies, regardless of which provider they choose.

Figure 19.2 Horizontal Restraints on Trade

Horizontal agreements are almost always struck down as per se violations of antitrust laws. Because competitors appear to make decisions based on their own self-interest rather than letting the market forces decide price and conditions, courts conclude that such agreements are not in the interest of consumers and the free market.

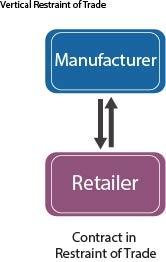

Vertical agreements occur between businesses at different places along the distribution chain of a given product. For example, a manufacturer suggests a sale price to a wholesaler of its product (i.e. “manufacturer’s suggested retail price”).

Figure 19.3 Vertical Restraints on Trade

Vertical agreements are usually subject to a “rule of reason” test to determine if they are illegal. The rule of reason test is a case-by-case analysis of the agreement, industry, effects, and intent of the businesses. Although it is possible to show that a vertical agreement is legal, it usually costs businesses a lot to litigate these types of cases.

Price Fixing

Price fixing is the artificial setting or maintaining of prices at a certain level, contrary to the workings of the free market. Horizontal price fixing is price fixing among competitors at the same level, such as retailers throughout an industry. Vertical price fixing is price fixing among businesses in the same chain of distribution, such as manufacturers and retailers attempting to control a product’s resale price.

One form of price fixing is predatory pricing. Predatory pricing occurs when a company lowers its prices below cost to drive competitors out of business. Once a predator rids the market of competition, it raises prices to make up lost profits. The goal of predatory pricing is to win control of a market or to maintain it.

Predatory pricing has three elements:

- The alleged predator is selling products below cost;

- The alleged predator intends that its competition goes out of business; and

- If the competitors go out of business, the alleged predator will be able to earn sufficient profits to recover its prior losses.

Predatory pricing cases are often hard to win because it is difficult to prove the alleged predator’s intent.

Division of the Market

Division of the market occurs when businesses agree to exclusively sell products or services in specific geographic territories. A horizontal division of the market is when competitors enter into an agreement to not compete for customers by dividing a geographic area into separate sales territories. A vertical division of the market is when a manufacturer and its wholesalers agree to exclusive distributorships in a given territory.

Exclusive distributorships are usually legal unless the manufacturer has dominant power in the overall market. For example, Wendy’s grants exclusive distributorships to its franchisees to avoid oversaturation in a given geographic area. As long as Wendy’s is not the only fast food restaurant within a particular market, the exclusive distributorships will be upheld. This is because Wendy’s has a legitimate business interest in not diluting the value of its franchises, which does not restrict consumers’ choice of fast food restaurants in the overall market.

Group boycotts

A boycott is an action designed to socially or economically isolate an adversary. A group boycott is an agreement between two competitors who refuse to do business with a third party unless it refrains from doing business with an actual or potential competitor of the boycotters. Group boycotts may be either horizontal or vertical.

Figure 19.4 Horizontal Group Boycott

Exclusionary Contracts

Exclusionary contracts require businesses to buy or lease products on the condition that they do not use the goods of a competitor of the seller. The most common types of exclusionary contracts are tying arrangements and exclusive dealing arrangements.

A tying arrangement occurs when a buyer is not permitted to purchase one item without purchasing another. These are often called “bundling packages.” These arrangements benefit a seller because it allows the seller to wed a popular item with one that is less desirable and would not get as many sales independently.

Under the rule of reason test, a tying arrangement is illegal when:

- The agreement involves two distinct products not closely related to each other;

- Commerce is impacted significantly; and

- The seller has sufficient economic power in the tying product to enforce the tie-in.

An exclusive dealing arrangement exists when a buyer agrees to purchase all of its requirements from a single seller or a seller agrees to sell all of its output to a single buyer. Exclusive dealing arrangements are illegal when they substantially lessen competition or tend to create a monopoly.

Mergers and Acquisitions

Regardless of a business’s intention when merging or acquiring another business, a merger or acquisition is prohibited when it may substantially lessen competition or may create a monopoly. When analyzing a potential merger, the court considers:

- The relevant market;

- The pre-merger profile of the business; and

- The post-merger profile of the business.

As discussed above, the relevant market is determined by examining the relevant product or service market, as well as the geographic area of the business’s operations.

The pre-merger profile is determined by analyzing the type of merger, the size of the companies involved, and the concentration of the industry. Mergers may be horizontal, vertical, or conglomerate. Horizontal mergers are between competitors. Vertical mergers are between businesses within a supply chain. And conglomerate mergers are between companies in different industries. An example of a conglomerate merger is Amazon’s acquisition of Whole Foods in 2107.

The post-merger profile uses the same factors as the pre-merger profile but looks at the anticipated business after the merger.

19.5 Price Discrimination

Price discrimination is the practice of offering identical or similar goods to different buyers at different prices when the costs of producing the goods are the same. Price discrimination may violate antitrust laws if it reduces competition.

Price discrimination may be either direct or indirect. Direct price discrimination occurs when a seller charges different prices to different buyers. Indirect price discrimination occurs when a seller offers special concessions (such as favorable credit terms) to some, but not all, buyers.

The Robinson-Patman Act defines discrimination in terms of first, second and third lines. First line price discrimination is when the seller directly offers different prices to different buyers. For example, coffee sold to individual customers is priced differently. First line price discrimination is legal when the lower price is offered to customers who buy large quantities, use coupons, or are part of a loyalty program. It is also legal if the price difference is the result of manufacturing, sales or delivery costs. For example, coffee prices may be lower for Hawaiian coffee in Hawaii because there are less transportation costs involved than shipping coffee to the Continental United States.

Figure 19.5 First Line Discrimination

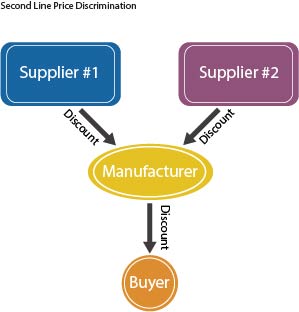

Second line price discrimination occurs when a manufacturer demands lower prices from suppliers. For example, large retailers often demand discount prices from manufacturers because they buy goods in large quantities. Second line price discrimination is legal as long as the negotiations for the lower price are done fairly and there is not a substantial anticompetitive impact in the market. When second line price discrimination results in larger businesses freezing out smaller competitors, it violates antitrust laws.

Figure 19.6 Second Line Price Discrimination

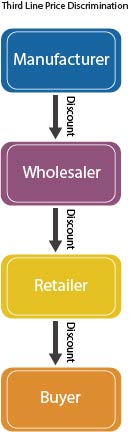

Third line price discrimination occurs when a customer of a customer of the seller is benefited by the seller’s actions. For example, a clothing manufacturer gives a price discount to a clothing wholesaler, who then passes the savings on to the retailer, who then reduces prices for consumers. The consumers ultimately benefit from the price discount given to the wholesaler by the manufacturer.

Figure 19.7 Third Line Price Discrimination

Price discrimination, at any line, is legal when a seller lowers prices in good faith to meet an equally low price offered by a competitor. If lower prices are a result of good faith, courts determine that the prices reflect market forces at work. In other words, the businesses are honestly competing for consumers. However, if the lowered prices are not done in good faith but are an attempt to undercut competition, then the business commits predatory pricing.

19.6 Enforcement

Antitrust laws impose both civil and criminal penalties. A private business that has been injured by anticompetitive practices may sue for damages. To encourage private enforcement, the Sherman and Clayton Acts award successful litigants treble (i.e. triple) damages and attorneys’ fees. To be successful, a plaintiff must show that an anticompetitive act directly resulted in a tangible injury.

However, most antitrust actions involve governmental enforcement. This makes sense because the government has the power to investigate and subpoena that private businesses do not. It also saves businesses a lot of money for the government to enforce the laws rather than through private litigation.

Both the Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission enforce antitrust laws. Both agencies may pursue civil and criminal remedies for violations of the law.

Civil remedies include:

- Injunctions (court orders prohibiting the business from committing further violations);

- Consent decrees (court-approved agreements in which a party does not admit wrongdoing but agrees to change its behavior); and

- Divesture orders (court orders requiring a company to sell its interest in an acquired company).

The Department of Justice may also pursue criminal charges for violations of antitrust laws. If convicted of a felony, individuals may be fined up to $1 million per violation and may be sentenced up to ten years in prison. A business may be fined as much as $100 million per violation.

19.7 Concluding Thoughts

The underlying tension of antitrust laws is the appropriate amount of regulation in a free enterprise system. By definition, a free enterprise market-oriented system should be free from governmental regulation. However, it is clear that some regulation and oversight is necessary to protect individuals and businesses from unethical and anticompetitive business practices. Even absent unethical practices, some businesses may be so successful that over time they gain enough market share to freeze out competition, and have less incentive to deliver quality products and services. As a result, the market may become stagnant, which is not in the best interest of the national economy or consumers. Antitrust laws attempt to protect consumers and the economy while allowing free enterprise to operate.