22

22.1 Introduction

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

- Distinguish between personal property and real property.

- Understand classifications of property.

- Examine methods of acquisition of real and personal property.

- Examine the landlord-tenant relationship.

- Understand how property is transferred through wills and trusts.

- Explore common land use regulations and environmental laws that businesses face.

Property refers to tangible and intangible items that can be owned. Ownership is a concept that means the right to exclude others. Legal systems create a peaceful means to acquire, retain, and divest property, and to settle property disputes. Businesses need to understand the legal system regarding both personal and real property because they often own or lease both. In addition, the government regulates how real property can be used as well as any environmental impact a business has.

22.2 Personal Property

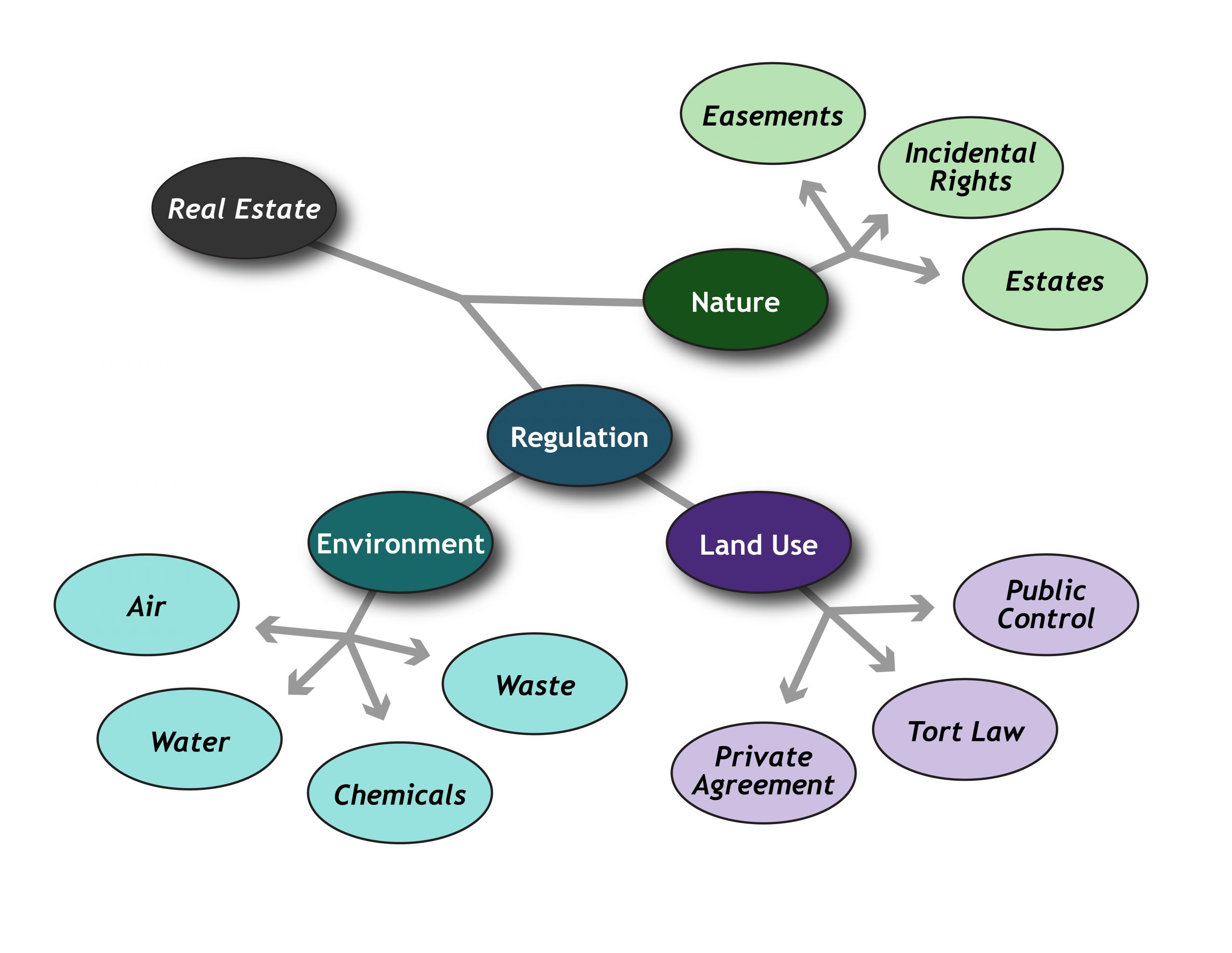

Property can be classified as real or personal. Real property is land, and certain things that are attached to it or associated with it. Real property is raw land, such as a forest or a field, as well as buildings, like a house or an office. Additionally, things associated with land, like mineral rights, are also real property. People often talk about real property by using the term real estate, which includes both real property and its related ownership interest.

Figure 22.1 Types of Real Estate Legal Issues

Personal property is property that is not real property. Tangible property is something that can be touched. Moveable, tangible personal property is called chattel. Many businesses exist to sell personal property. For example, the primary purpose of retailers is to sell personal property. Some property can also be described as fungible property. Property that can easily be substituted with identical property is said to be fungible. Types of fungible goods include juices, oil, metals such as steel or aluminum, and physical monetary currency.

Intangible property does not physically exist, but it is still subject to ownership principles, including acquisition, transfer, and sale. For instance, the right to payment under a contract, the right to exclude others from a patented product, and the right to prohibit others from using copyrighted materials are all examples of intangible property.

Personal property can become attached to the land as a fixture. A fixture is something that used to be personal property, but it has become attached to the land so that it is legally a part of the land. Fixtures are treated like real property so when real property is transferred, fixtures are transferred as a part of the real property. A ceiling fan for sale at a store is personal property. However, once the fan is installed in a house, it becomes a fixture and is part of the real property.

Some things that are attached to the land are not fixtures but are part of the real property itself. Imagine a farm with planted corn. The corn crop is an example of real property that can become personal property. While the corn is growing and still attached to the land, the corn is real property. Once it is picked from the stalk, the ear of corn becomes personal property.

Property also can be classified by ownership. Personal and real property can be private or public. Private property is owned by someone or some entity that is not the government, such as individuals, corporations, and partnerships. Private property can include real property like land or buildings, and personal property, such as vehicles, furniture, and computers. Property that is owned by the government is public property. Rocky Mountain National Park is an example of public property that is real property. Public property can also include personal property, such as vehicles and computers owned by state or local governments.

Methods of Acquisition of Personal Property

Personal property may be acquired in several different ways. For example, ownership by production occurs when one produces something. However, if an employee produces a good as part of his or her job, then the employer will own the property, not the employee. Ownership by purchase is the most common method of acquiring property. For example, if a customer buys a good, then the customer owns it through purchase from the manufacturer.

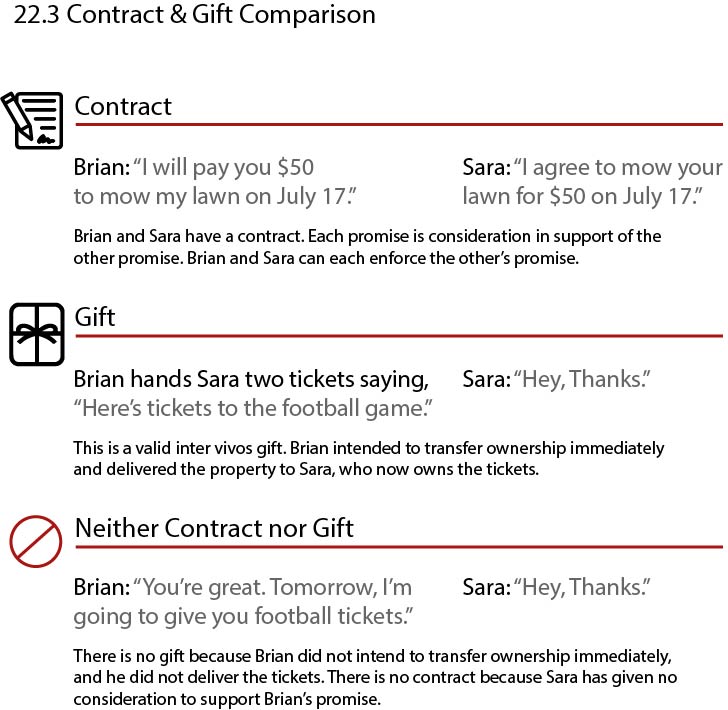

Property may also be gifted. A gift is a voluntary transfer of property. Generally, the donor of the gift must intend to gift the property, the donor must deliver the gift, and the gift must be accepted by the intended recipient. A conditional gift is a gift that requires a condition to be met before the gift will transfer, such as a wedding or graduation.

Property that someone finds can be classified in several ways. If property is abandoned, a person who finds it may claim ownership. However, the original owners of abandoned property must intend to relinquish ownership in it. For example, if someone takes a chair to the landfill, he or she has abandoned the chair. Someone may come along and take legal possession of it. However, if the property is simply lost or mislaid, then the finder must relinquish it once the rightful owner demands its return. Another classification of personal property applicable to found property is treasure trove. A treasure trove is money or precious metals, like gold, which is hidden in the ground or other private place by an unknown owner. Whoever finds a treasure trove becomes the owner unless the true owner (i.e. the person who hid it) comes forward.

| Type of Property | Description | Rights of Finder | Rights of Owner |

| Abandoned | Owner intentionally parted with property with intent to relinquish ownership rights | Finder acquires rights to the property | None |

| Lost | Owner unintentionally parted with possession of the property | Finder has rights to the property against everyone except the owner | Owner has right to have property returned because owner never lost ownership interest |

| Mislaid | Owner intentionally placed property in a specific place but has forgotten where | Finder has no rights and cannot keep property | Owner has right to have property returned because owner never lost ownership interest |

| Treasure Trove | Owner intentionally hid property | Finder acquires rights to the property unless the owner comes forward | Owner must come forward to maintain right to property; if not, finder becomes new owner |

Bailment

Sometimes it is necessary to intentionally leave personal property with someone else. A bailor is someone in the rightful possession of personal property who gives the property to someone else to hold, who is called a bailee. A bailment is the arrangement in which the personal property is exchanged. The bailee agrees to accept the property and has the duty to return it. For example, a customer gives clothes to a dry cleaner. The dry cleaner is a bailee and has a duty to return the clothes (personal property) upon demand by the customer, who is the bailor.

Bailments may be voluntary or involuntary. A voluntary bailment is created when intention exists to create the bailment, as described in the dry cleaner example above. An involuntary bailment is created when someone finds lost or mislaid property. The finder may not destroy the property, though the duties that he or she owes regarding the property may vary from state to state.

Bailment is common in business, including placing packages with common carriers for delivery, warehousing goods with a third party, or taking clients’ or customers’ automobiles in a valet service.

The duty of care that the bailee owes to a bailor depends on the nature and value of the property involved, as well as who benefits from the bailment. In general, a higher standard of care is required for more valuable property. Damages in a bailment case are based on the retail replacement value of the property.

22.3 Real Property

Real property is land, and certain things that are attached to or associated with it. Real property includes undeveloped land, like a field, and it includes buildings, such as houses, and office buildings. Real property also includes things associated with the land, like subsurface rights (rights to minerals and things found beneath the surface).

Methods of Acquisition

Real property may be acquired by purchase, inheritance, gift, or through adverse possession. Ownership rights are transferred by title. Ownership of real property means that the owner has the right to possess the property, as well as the right to exclude others, within the boundaries of the law. If someone substantially interferes with the use and enjoyment of real property, the owner may bring a nuisance claim. Similarly, the owner may bring a trespass claim against those who enter the land without consent or permission.

Purchase

Land owners may convey or sell part or all of their land interests. Different types of deeds convey different types of interests. A quitclaim deed, for instance, conveys whatever interests in title that the grantor has in the property to the party to whom the quitclaim is given. That means if the grantor has no interests in the real property, a conveyance by quitclaim will not grant any interests in the property. By comparison, a warranty deed conveys title and the seller gives a warranty against defects in title as well as encumbrances. Buyers typically demand a warranty deed when they purchase property because the seller assumes the risk of the title not being clear.

After title is transferred by the deed, the deed is recorded in the county where the property is located. Recording a deed is important because it places others on notice about who owns the property. States have different rules about who is considered the legitimate owner when a conflict in ownership claim exists. A bona fide purchaser is a purchaser who takes title in good faith, with no knowledge of competing claims to title. Many states recognize a bona fide purchaser’s rights to ownership over those who did not properly record a deed.

Inheritance

Another common way in which real property may be obtained is through inheritance. Real property may be bequeathed through a will or may be transferred by state law when someone dies without a will. Generally speaking, people have the right to dispose of their property as they wish when they die, providing that their will or other transfer instrument meets their state’s requirements for validity. If someone dies without living relatives, the government becomes the owner of the property.

Gift

Real property may also be acquired through a gift. A gift is valid when:

- The person giving property intends to make the gift;

- The person delivers the deed to the recipient; and

- The recipient accepts the gift.

If one of these elements is not met, then title will not be conveyed.

Figure 22.2 Comparison of Contract and Gift

Adverse Possession

A less common way to acquire real property is through the doctrine of adverse possession. Adverse possession is when someone who is not the owner of real property has claimed the real property for his own. This is referred to as “squatter’s rights.” If land sits idle at the owner’s hands but someone else puts it to use, then the law may favor the user’s claim to the land over that of the actual owner. Adverse possession claims often occur around property lines, where one party has routinely used another’s property because a fence has been misplaced.

Figure 22.3 Adverse Possession Cartoon

Interests and Scope

Owning real property carries many responsibilities, as well as the potential for great profit and great liability. It is important to learn how to protect against potential liability of property ownership. For instance, if a toxic waste site is discovered on real property, the owner may be liable for its cleanup, even if he or she did not realize that such a site was there when purchasing the land. Each buyer of real property has a duty to exercise due diligence when purchasing land. A purchaser should never agree to buy land “sight unseen” or without a professional inspector.

It is important to know the duties of landowners, how to limit liability associated with the ownership of land, and when severance of liability occurs.

Duties of Landowners

Landowners owe different duties to different types of people who enter their land. These responsibilities vary, depending on whether the person is a trespasser, a licensee, or an invitee.

A trespasser is a person who intentionally enters the land of another without permission. A landowner has a duty to not intentionally injure a trespasser. For instance, booby traps and pitfalls are illegal. Trespassers injured from such traps have valid claims against the landowner. However, if trespassers are injured from unknown or unforeseeable dangers, the owner is not usually liable.

A licensee is someone who has permission to be on the land. Landowners have a higher duty of care to such a person. Licensees include delivery people, meter readers, and utility workers. A landowner must not intentionally injure a licensee and must warn the licensee of known defects. For example, if a landowner knows that the steps to his or her porch are icy, he or she has a duty to warn a licensee that those steps are icy. Failure to do so may result in liability for the landowner.

An invitee is someone who has entered real property by invitation. Businesses and public places that want members of the community to visit have issued invitations to the public. Landowners must inspect their property for defects, correct those defects when found, and warn invitees about such defects. For example, a grocery store must clean up spills as quickly as possible and put up a “caution” sign in that area.

Ownership Interests in Real Property

Different types of interests may be owned in real property. For example, real property may be owned without restriction, subject only to local, state, and federal laws. Sometimes ownership interests may be narrower, subject to conditions, the violation of which can lead to loss of those ownership interests.

The most complete ownership interest recognized by law is called fee simple absolute. This ownership allows the owner complete control over the land and lasts until the owner dies or conveys the property to someone else. Generally, if someone wants to buy real property, he or she is looking to buy property in fee simple absolute.

Compare that with a defeasible fee. A fee simple defeasible is subject to a condition of ownership or to some future event. For instance, if an owner donates land to a city “so long as it is used as a public greenway,” then the land would be owned in defeasible fee by the city as long as it maintains it as a public greenway. Once the condition is violated, the land would revert back to either the original owner or whoever owned the reversion interest, which is a future interest in real property.

Another ownership interest is a life estate. This interest is measured by the life of the owner. For example, a person could grant ownership rights in real property to a parent for the length of his or her life, but then the property would be returned upon the parent’s death. A common investment, known as a reverse mortgage, employs the concept of life estate. A reverse mortgage is an arrangement where the purchaser of real property agrees to allow the seller of the property to retain possession of the property for a specified period of time (such as the remainder of his or her life) in exchange for the ability to purchase the property at today’s price. These arrangements essentially gamble on life expectancies of the sellers of real property by granting life estates to them in the property.

Property can be owned by more than one owner. Several types of co-ownership interests are recognized in law. These ownership interests are important for matters of possession, right to transfer, right to profits from the land, and liability. For example, tenancy in common describes an ownership interest in which all owners have an equal right to possess the whole property. Compare this to joint tenancy, in which the surviving owner has the right of survivorship. If one of the owners dies, his or her property interests automatically transfers to the remaining owner(s).

These different interests are created by specific wording in the instrument of conveyance. An owner in tenancy in common may sell or transfer his or her rights without seeking permission from the other owners. This is because owners in a tenancy in common have the unilateral right to transfer their interests in property. Conversely, to transfer one’s interests in a joint tenancy, the consent and approval of the other owners is required.

Scope of Interests in Real Property

Scope of ownership determines what can (or cannot) be done with the land. The surface of the land and the buildings that are attached to the land are what most people think of about ownership of real property. However, land interests also include subsurface or mineral rights, and right to light or to a view. Moreover, water rights are granted differently, depending on whether the property is in the western or the eastern United States. Additionally, easements (the right to cross or otherwise use someone’s land for a specified purpose) and covenants (guides or restraints on how one may build on their land) grant certain rights to non-possessors of land.

Subsurface Rights

Subsurface or mineral rights are rights to the substances beneath the actual surface of the land. Purchasing mineral rights allows the owner to extract and sell whatever exists under the surface of the land, such as oil, natural gas, and gold.

Water Rights

Water rights are determined in two different ways in the United States. Generally speaking, states east of the Mississippi River follow a riparian water rights doctrine, which means that those who live next to the water have a right to use the water. The water is shared among the riparian owners. However, most western states use the prior appropriation doctrine, which grants rights to those who used those rights “first in time.” Under this concept, the use must be beneficial, but the owner of the right need not be an adjacent landowner. This policy has resulted in claims by “downstream” users having priority over landowners where water runs through the land. For example, casinos in Las Vegas, Nevada may have priority of water rights over ranchers in Colorado where a tributary runs through the ranch. Prior appropriation is a “use it or lose it” doctrine.

Easements and Covenants

Easements and covenants are nonpossessory interests in real property. An easement can be express or implied and it gives people the right to use another’s land for a particular purpose. For example, a common easement is for utility companies to enter private property to maintain poles and power lines. Other examples include sidewalks and a landlocked property having an easement across another piece of property for the purpose of a driveway or walkway.

A covenant is a voluntary restriction on the use of land. Common covenants are homeowners associations’ rules, which restrict the rights of the owners to use their land in certain ways, often for aesthetic purposes. For instance, such covenants might require houses subject to the covenant to be painted only in certain approved colors, or they might contain prohibitions against building swimming pools.

Some covenants and easements “run with the land,” which means that the restrictions will apply to subsequent owners of the property. Whether a covenant or easement runs with the land depends on the type of interest granted.

Landlord-Tenant Relationships

A leasehold interest also may be created in real property. A tenant has the right to exclusive possession of the real property and the duty to follow the rules of occupancy set out by the landlord. The landlord has the right to be paid rent and the duty to ensure that the premises are habitable. If one party does not perform under the lease as required, the other party may seek a legal remedy for breach of contract. Most state laws also impose duties on landlords to maintain safe and habitable conditions on the property. Tenants also have a duty to use the premises properly and not to damage the property beyond normal wear and tear.

Different types of tenancies may be created:

| Type of Tenancy | Description |

| Tenancy for years |

|

| Periodic tenancy |

|

| Tenancy at will |

|

| Tenancy at Sufferance |

|

Tenancies may be created for residential or commercial purposes. Commercial leases typically last for longer periods of time than residential leases. Many of the same responsibilities and duties exist with commercial leases, but there are some important differences. For example, a commercial tenant may demand that the landlord refuse to rent to a competitor of the tenant within the same building.

Lease interests are assignable unless those rights are expressly restricted by agreement. This means that the rights conveyed by the lease may be transferred to another party by assignment, unless expressly prohibited by the lease. Common restrictions on assignment in residential leases is a no-subletting clause. Just as the owner of real property may sell any or all of his or her interests, any ownership interest in real property may also be leased. For example, someone who owns the subsurface rights of land may lease the right to drill for oil or gas to another.

22.4 Wills and Trusts

Both real and personal property may be transferred to another owner through wills and trusts. Although most people think of wills and trusts as a tool for conveying property owned by individuals, businesses property often needs to be transferred when the business owner dies. This is especially true for sole proprietorships and partnerships.

A will is a document by which an individual directs his or her estate to be distributed upon death. Wills must be in writing and signed by the individual(s) making them. Although state laws regarding wills vary slightly, most states require:

| Requirement | Description |

| Legal age |

|

| Testamentary intent |

|

| Testamentary capacity |

|

| Signature |

|

| Witnesses |

|

A trust is a property interest held by one person or entity at the request of another for the benefit of a third party. For a trust to be valid, it must involve specific property, reflect the person’s or entity’s intent, and be created for a lawful purpose. Trusts are very popular for leaving property to benefit children who are under 18 years old, elderly, and people with disabilities.

When planning how to distribute property upon death, it is important to understand the difference between probate and non-probate assets. Probate is the process through which a court determines how to distribute property after someone dies. Some assets are distributed to heirs by the court (probate assets) and some assets bypass the court process and go directly to beneficiaries (non-probate assets). Probate assets generally are subject to inheritance taxes and distribution can be delayed until the court orders the distribution of the assets. Because of these drawbacks, many individuals prefer non-probate assets.

| Probate Assets | Non-Probate Assets |

|

|

Death of a property owner impacts the ability to transfer property. The ownership interest dictates how the property may be transferred.

| Type of Ownership | Death of Owner | Transfer | Where Available |

| Tenancy in Common | Owner’s interest passes to heirs | Owner may transfer interest without agreement of co-owners | All states |

| Joint Tenancy | Owner’s interest passes to the remaining joint tenants as non-probate asset | Owner may not transfer interest without agreement of co-owners | All states |

| Tenancy by Entirety | Owner’s interest passes to the surviving spouse | Owner may not transfer interest without agreement of spouse | Approximately half of the states |

| Community Property | Half of owner’s interest passes to the surviving spouse & other half passes to other heirs | Owner may not transfer interest without agreement of spouse | Only 9 states: Arizona, California, Idaho, Louisiana, Nevada, New Mexico, Texas & Washington |

If someone dies without a will or trust, the probate court will determine:

- The nature and value of the decedent’s estate;

- The nature and value of any outstanding debts and tax obligations;

- Whether the decedent has any heirs;

- The identity of the heirs and their relationship to the decedent; and

- What, if anything, the heirs are entitled to receive from the decedent’s estate.

The essential role of the probate court is to ensure that the deceased person’s creditors are paid and that any remaining assets are distributed to the proper beneficiaries. However, this process takes time and costs money from the deceased person’s estate. And there is no guarantee that the deceased person intended his or her property to be distributed based on the state’s rules on who qualifies as an heir and what they are entitled to receive. Business assets owned by the deceased person may complicate the probate process even more.

22.5 Land Use Regulation

A nuisance is a condition or situation, such as a loud noise or foul odor, that interferes with the use or enjoyment of property. Courts balance the utility of the act that is causing the problem against the harm done to neighboring property owners. For example, restrictions exist on when manufacturing plants may operate to not interfere with sleeping patterns of neighbors.

Nuisance can be both intentional and unintentional, as well as public or private. A public nuisance is an unreasonable interference with a right common to the general public, such as a condition dangerous to the public’s health or a restriction on the public’s access to public property. Many jurisdictions also include conduct that is offensive to the community’s moral standard to regulate the placement of adult industries in residential neighborhoods. Public nuisance claims often include manufacturing noises, smoke and smells. A private nuisance is a condition that interferes with a person’s enjoyment of their property that does not involve a trespass. For example, cigarette smoke entering a neighbor’s house from a smoker on an adjacent property is a private nuisance.

Figure 22.4 Public Nuisance Street Sign

Figure 22.5 Private Nuisance Example

Most states have passed laws that allow local governments to regulate zoning. Zoning ordinances are laws passed by counties, cities, and municipalities that regulate land development. These ordinances determine whether commercial or residential buildings can be built in an area, how tall buildings may be, and how much green space must be maintained. They also apply to existing buildings and regulate whether a building may be converted from residential property to commercial, as well as what type of commercial property it may be. For example, many zoning ordinances regulate the types of businesses that may be located next to schools and hospitals.

Eminent domain is the power of the government to take private property for public use. A governmental entity may need to build or expand highways, public transport systems, or public housing. To address the public’s need, the government can take private property and use it for the good of the community. All levels of government–federal, state, and local–have the power of eminent domain. The Fifth Amendment of the US Constitution requires that any owners of private property taken for public use must be given “just compensation.” Just compensation means fair market value for the land.

22.6 Environmental Law

Federal and state governments have passed environmental laws to limit pollution and protect the health and welfare of the public. Although most people are supportive of these laws in theory, the practical implementation of them has been controversial. Underlying the political debate is the question, how should the law balance the costs and benefits of environmental decisions?

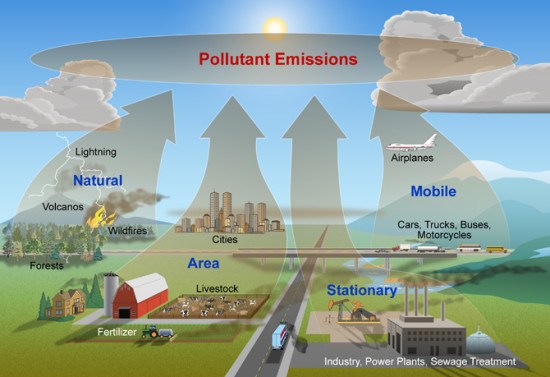

Clean Air Act

In 1963, Congress passed the Clean Air Act to regulate air pollution. Under the Clean Air Act, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has the authority to regulate both the total amount of existing air pollution and its ongoing production. The Clean Air Act was passed to address concerns of global warming and acid rain.

Figure 22.6 EPA Seal

The Clean Air Act requires the EPA to set national air quality standards that protect public health and provide an adequate margin of safety without regard to cost and to implement them if appropriate and necessary. This “without regard to cost” directive has been heavily litigated. In 2015, the US Supreme Court ruled that the EPA must consider costs as part of its analysis of whether the standards are “appropriate” and necessary. In other words, a regulation is not “appropriate” if it does more harm than good.

The Clean Air Act is a federal law that is implemented through the states. After the EPA sets air quality standards, states must enforce them. States may implement more stringent air quality standards than the EPA requires, but they cannot do less. Therefore, businesses must comply with both state and federal agencies to ensure their compliance with the Clean Air Act.

A controversial aspect of the Clean Air Act is that it allows for trading of credits. For example, a manufacturer who removes more carbon monoxide than necessary from its emissions is given a “credit” from the EPA. These credits can then be sold to another manufacturer that does not remove enough to be compliant with the law. The rationale is that credits make it profitable for manufacturers to invest in technology that pollutes less than is legally required. By giving a market incentive to industries to protect the environment, there will be less need for governmental enforcement.

The Clean Air Act imposes daily fines for emission violations, as well as punitive damages and criminal liability for corporate officers who knowingly and willfully violate the law. As a result, the Clean Air Act is a law that manufacturers must take seriously.

Figure 22.7 Common Air Pollutants

Clean Water Act

Congress passed the Clean Water Act in 1972 to regulate water quality of navigable waters. Similar to the Clean Air Act, the EPA sets standards that are enforced by the states. The intent of the Clean Water Act is to keep water clean for recreational use and to protect fish and wildlife. It requires a discharge permit to release waste into navigable water.

Figure 22.8 Photo of discharge of industrial waste into river

The EPA sets limits, by industry, on the amount of each type of pollution that can be discharged in a given area, as well as the type of technology that can be used to treat water. As a result, the two biggest issues when enforcing the Clean Water Act are (1) is the waterway navigable? and (2) what is the best available technology that each industry can use to reduce pollution. Both issues are heavily litigated.

The Clean Water Act also requires the EPA to set national standards for water quality in general. It is worth noting that water quality standards vary depending on the use of the water. Water quality for drinking is the highest, with wildlife and recreation higher than irrigation and industry. As a result, even businesses that are not discharging waste into navigable waterways are subject to EPA standards of water quality on their premises. For example, a retailer must comply with water quality requirements in its drinking fountains and bathrooms.

Like the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act imposes daily fines for emission violations, as well as punitive damages and criminal liability for corporate officers who knowingly and willfully violate the law.

Waste Disposal

Waste disposal, especially of chemicals, has been an area of increased regulation over the past decades. The disposal of ordinary garbage is primarily regulated by the states. However, the federal government sets minimum standards for landfills and regulates how states manage garbage. Most of these regulations are “invisible” to businesses and individuals.

Figure 22.9 Improper Toxic Waste Disposal

Toxic waste, on the other hand, directly impacts manufacturers. In 1976 Congress passed several laws to address the problem of industrial waste and toxic waste. Toxic waste is hazardous or poisonous substances that cause an increase in the death rate or serious irreversible illnesses. Toxic waste includes arsenic, asbestos, clinical waste (i.e. syringes), cyanide, lead, and mercury. Many of these chemicals are found in batteries, electronics, and household cleaners. Manufacturers have a “cradle to grave” responsibility for all hazardous and toxic waste. This means that hazardous waste must be (1) tracked from creation to final disposal and (2) disposed of at a certified facility.

To clean up hazardous waste that was illegally dumped in the past, Congress passed the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA), which is popularly known as “Superfund.” The philosophy of Superfund is that the polluter pays. Therefore, former and current owners of a site on which hazardous waste is found or who transported waste to the site are strictly liable for remediation of the land. The law has an exception for innocent landowners who unknowingly purchased the land. However, that exception is narrowly applied.

Environmental Impact Statements

The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) requires all federal agencies to prepare an environmental impact statement (EIS) for every major federal action that significantly affects the quality of the human environment. An EIS is required not only for actions by the federal government, but also activities regulated or approved by the government. Therefore, private businesses that need federal approval to open or expand their operations are subject to this requirement. For example, an EIS was needed before expanding the Snowmass ski area in Aspen because the US Forest Service was required to approve the expansion.

An EIS must include:

- A description of the environmental impact of the proposed action;

- An estimate of the energy requirements for the project;

- A description of potential adverse effects on the urban quality, including historic and cultural resources;

- Identification of the short-term and long-term impact on the environment;

- A description of any irreversible impact on the environment;

- A plan of how to mitigate any adverse environmental impact; and

- A discussion of possible alternatives.

The process of preparing an EIS can be long and expensive. After an EIS is written, the federal agency must allow for public comments and hold a hearing. Therefore, a private business may have its EIS scrutinized and commented on by interest groups and competitors before receiving federal approval. There is also a risk to the business that the government agency denies the business’s request based on public comments and concerns.

22.7 Concluding Thoughts

Property is classified as real property or personal property, tangible or intangible, and private or public. Personal property can be transformed into real property when it is affixed to the land. Real property can be transformed into personal property when it is severed from the land. Personal property can be acquired for ownership through production, purchase, or gift or, in certain circumstances, by finding it. Bailments are legal arrangements in which the rightful possessor of personal property leaves the property with someone else who agrees to hold it and return it on demand.

When thinking about acquiring property, it is important to understand the rights and duties associated with acquiring it, the protections afforded to the owner, and how to transfer it to another party at the time of sale, lease, or licensing the right to use it. Real property includes land and the buildings attached to it, as well as the minerals below it. Personal property is everything else. Because property ownership includes exposure to liability, businesses need to take steps to protect people on their real property from hazards. Businesses are also subject to land use regulations and environmental laws for the use of their real property.

Real and personal property may be transferred to another owner through wills and trusts upon the death of the original owner. Businesses property often needs to be transferred when the business owner dies, and not having a will or trust in place to convey the property can complicate the probate process. Non-probate assets are popular to avoid inheritance taxes and delays in distributing assets.

Environmental laws have a big impact on businesses, especially manufacturers. The Clean Air Act and the Clean Water Act are federal laws that are implemented through the states, so businesses must work with both state and federal governments to ensure they are legally compliant. Businesses that want to open or expand their operations are required to prepare an environmental impact statement if they need federal approval.