13

Chapter Outline

Response to Intervention (RtI)

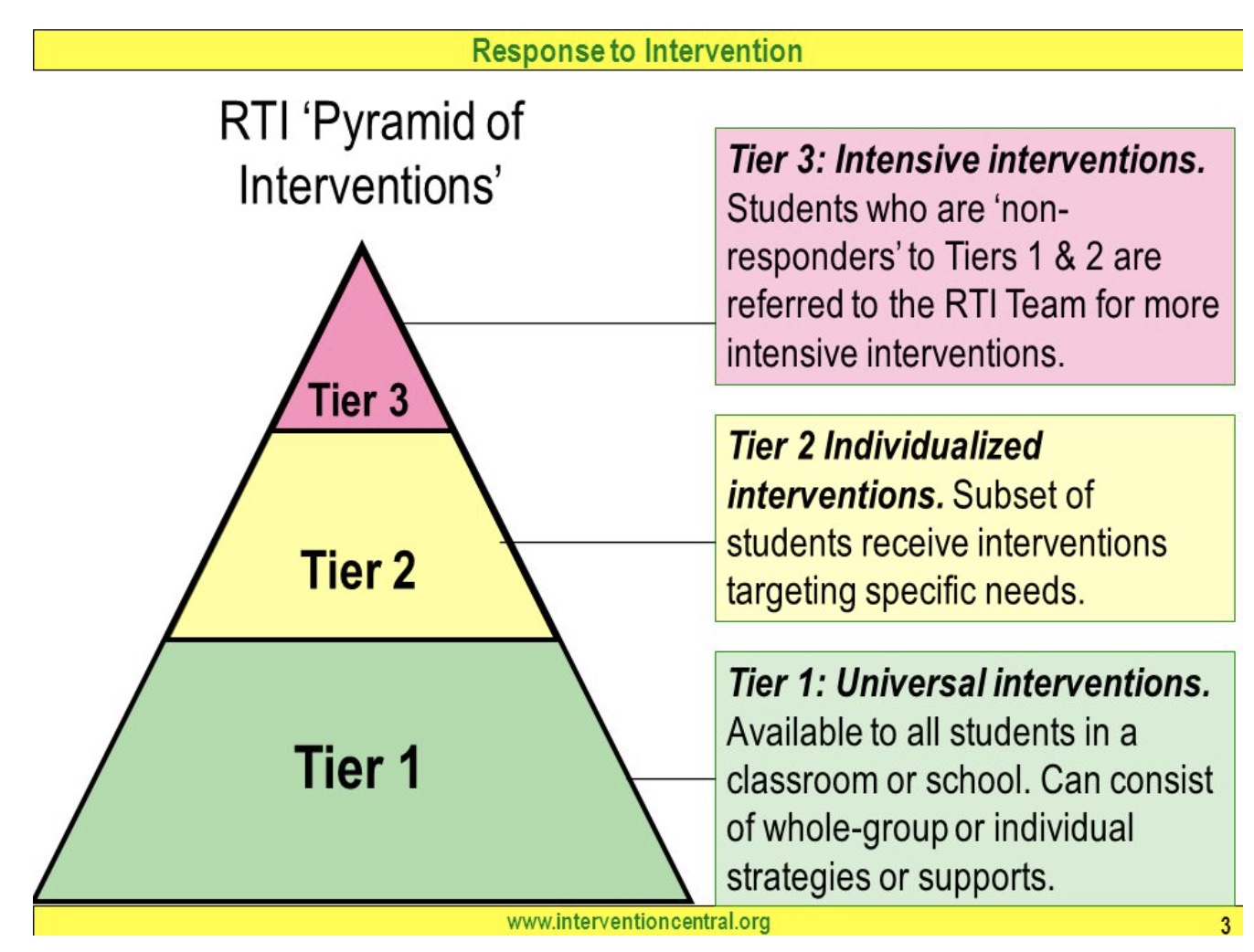

Response to Intervention (RtI) is a tiered model designed to help identify and support students with learning and behavior needs. The RtI framework consists of three tiers, referred to as Tier 1, Tier 2, and Tier 3. We will examine this framework in the next few paragraphs.

The Rehabilitation Act established a very broad definition of disability in 1973, which was subsequently incorporated into the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) in 1990. Any individual who has an impairment that significantly impacts their ability to perform a major life function (such as walking, speaking, learning, or sitting) is defined as an individual with a disability and receives protection under these two laws (Rehabilitation Act, 1973). The Rehabilitation Act and ADA are civil rights laws that evolved from the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and extend the protections of educational access and equal opportunity to individuals with disabilities.

Broadly, the Rehabilitation Act addresses disability-related discrimination by any institution that receives public funding and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act specifically applies to schools, including institutions of higher education. The ADA provides protections in all public facilities other than churches and private clubs (Smith, 2001). Generally speaking, educators implement the protections of Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act and the ADA by providing accommodations that allow students with disabilities to fully access curricular materials and physical spaces. In most cases, accommodations provided through Section 504 are specific to the needs of the individual student and are documented in a 504 plan. Examples include providing technology with speech-to-text features for a student with physical impairments that significantly impact writing or a chair with armrests for a student who needs additional support for core stability. Conversely in school settings, ADA supports are often proactively added to public spaces and materials to provide accessibility for all. Examples include closed captioning of videos, curb cuts, ramps or elevators, and fire alarms that provide both auditory and visual alerts.

In contrast to the Rehabilitation Act and ADA, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act (IDEIA) has a much more specific definition of disability. An individual must have characteristics that align with one or more of 14 eligibility categories (referenced in Table 2.2) and those characteristics must have a negative impact on learning. A very specific evaluation process is used to determine if a student qualifies for services under the IDEIA.

Table 2.2: Categories of Disability under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act

|

|

The IDEIA provides protections to students between the ages of 3 and 21, though the protections are discontinued when a student graduates from high school with a standard diploma. The law is focused on ensuring that students with disabilities receive a Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE). This means that students must receive specially designed instruction, including special education and accommodations, that allows them to make meaningful progress toward the curriculum and their individual learning goals. All of these services must be provided at public expense. A unique learning plan for each student, called an Individualized Education Plan (IEP), must be developed annually by a team that includes general and special education teachers, administrators, the student’s parents, and the student (when age-appropriate). Additionally, the IEP must be implemented in the Least Restrictive Environment (LRE). The principle of LRE states that students with disabilities must be educated in the same setting as their peers who do not have disabilities, unless it is not possible for the student to make progress in that setting even when additional supports are added.

Critical Lens: IDEA or IDEIA? The Lingo of Special Education

In 1990, Congress reauthorized the Education for All Handicapped Children Act and renamed it the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. The acronym IDEA quickly became embedded in the lingo of education, referencing the law itself and the “idea” that equal educational access for individuals with disabilities was becoming a valued part of our educational system. In 2004, Congress reauthorized the law again, providing some additional clarity and protections. They named this update the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act, making the official acronym IDEIA. Although IDEIA is the most technically correct abbreviation, educators still use the word “idea” when discussing the law.

With the reauthorization of IDEIA in 2004, RtI gained popularity as a model designed to identify and provide early intervention as a preventative method for students who are at risk of learning difficulties. Many states have adopted the Multi-Tiered System of Supports (MTSS) model instead of RtI. Although we are not going to expand on the similarities and differences of these two models, it is important to note that, as the name implies, RtI is often a component of MTSS.

RtI Framework

As previously mentioned, the RtI framework consists of three tiers. One of the main premises of RtI is the assessment and monitoring of students’ progress. States have flexibility on how to enact RtI, but they generally follow some basic principles. At the beginning of each school-year, all students are go through a universal screening process in order to identify those who are potentially at risk of falling behind. After a specified timeframe and consistent monitoring, students who do not demonstrate expected progress might be referred to a different tier within RtI.

The basic principle of RtI is that every child should receive high-quality, research-based core instruction in their regular classroom. The regular education that every child receives in school is the Tier 1 in the RtI framework. By improving classroom instruction and implementing evidence-based practices, fewer students are expected to need educational intervention. Ideally, 75-85% of students will thrive in Tier 1.

The basic principle of RtI is that every child should receive high-quality, research-based core instruction in their regular classroom. The regular education that every child receives in school is the Tier 1 in the RtI framework. By improving classroom instruction and implementing evidence-based practices, fewer students are expected to need educational intervention. Ideally, 75-85% of students will thrive in Tier 1.

However, some students struggle even when receiving high-quality instruction. Such students are referred to Tier 2, where they receive an extra layer of support. Student in Tier 2 work in smaller groups and receive differentiated instruction. For instance, some students struggle reading due to a lack of decoding skills, while other students might not speak English as their first language. Tier 2 is designed to provide differentiated interventions to meet the individual needs of each student. Tier 2 intervention is provided in addition to Tier 1. Ideally 10-20% of students will need Tier 2 intervention.

Finally, students who do not show the expected improvement in Tier 2 can be referred to Tier 3. Tier 3 intervention is more individualized and intensive. Students normally receive intervention in very small groups, generally up to three students, or individually. Tier 3 intervention also takes place more often and/or for a larger amount of time. Only 5-10% of students are expected to need this type of intervention. Students in Tier 3 who still do not reach their educational goals might be referred to Special Education (SPED).

Universal Design for Learning

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is a framework to improve and optimize teaching and learning for all people based on scientific insights into how humans learn.

The UDL Guidelines are a tool used in the implementation of Universal Design for Learning. These guidelines offer a set of concrete suggestions that can be applied to any discipline or domain to ensure that all learners can access and participate in meaningful, challenging learning opportunities.

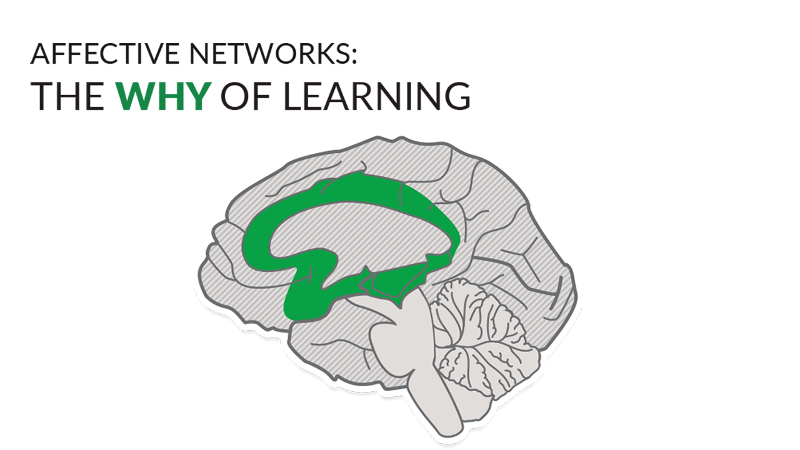

Engagement

For purposeful, motivated learners, stimulate interest and motivation for learning.

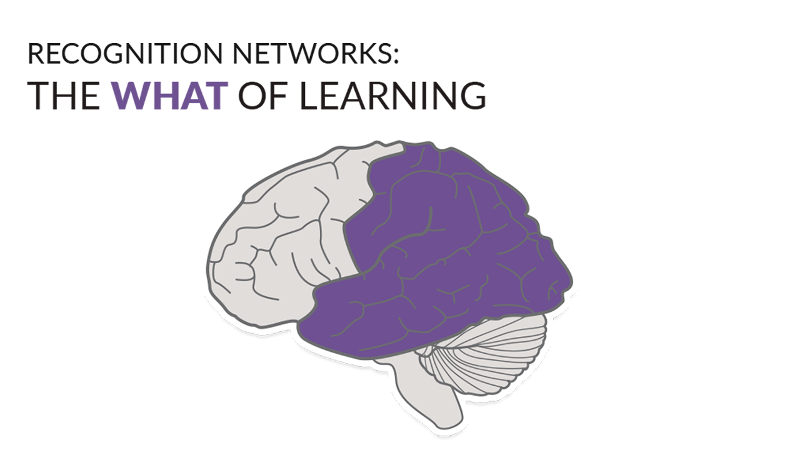

Representation

For resourceful, knowledgeable learners, present information and content in different ways.

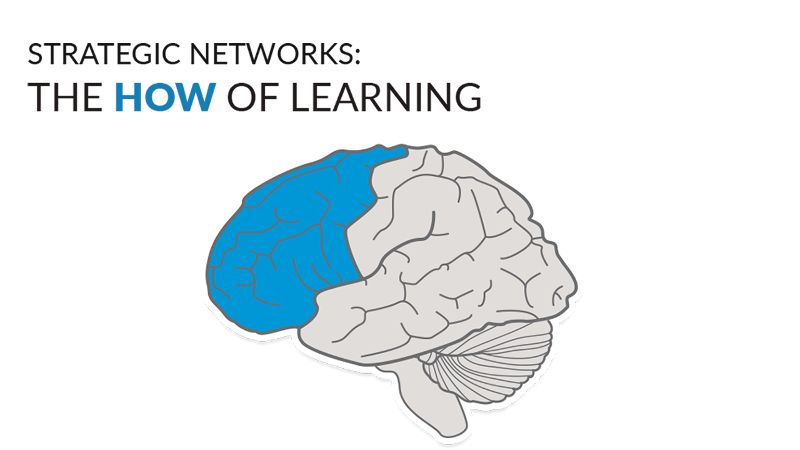

Action & Expression

For strategic, goal-directed learners, differentiate the ways that students can express what they know.

Additional Similarities and Differences that Can Impact Learning

In addition to the influences on student learning we have already explored in earlier chapters, there are two additional sub-groups of students you will work with in your future classroom that have very unique learning strengths and needs: Emerging Bilinguals (EBs), commonly referred to as English Learners (ELs), and students with disabilities.

Gifted Learners

Teachers often find it difficult to understand the specific needs of gifted students, which means advanced students often do not get the support they need in the classroom. A common response is “they will do fine all by themselves.” However, that is far from accurate. The reality is, however, without a doubt the most difficult student in your classroom is generally the one who finishes every assignment in less than five minutes and requires constant redirection. Gifted learners have unique needs to help them reach their full potential.

The Davidson Institute has a long history of supporting gifted learners. Check out the weblink above and browse the Davidson website.

There are generally five strategies that teachers can employ to help their gifted learners to thrive:

-

Familiarize Yourself with the Characteristics of Intellectually Gifted Students

Not all gifted students in your classroom will be identified and even those who are may not always appear to be gifted. Gifted students come from all ethnic groups, they are both boys and girls, they live in both rural and urban areas and they aren’t always straight A students.

Students who are intellectually gifted demonstrate many characteristics, including: a precocious ability to think abstractly, an extreme need for constant mental stimulation; an ability to learn and process complex information very rapidly; and a need to explore subjects in depth. Students who demonstrate these characteristics learn differently. Thus, they have unique academic needs. Imagine what your behavior and presentation would be like if, as a high school junior, you were told by the school district that you had to go back to third grade. Or, from a more historical perspective, what if you were Mozart and you were told you had to take beginning music classes because of your age. This is often the experience of the gifted child. Some choose to be successful given the constructs of public school and others choose to rebel. Either way, a few simple changes to their academic experience can dramatically improve the quality of their lives — and, mostly likely, yours!

-

Let Go of “Normal”

In order to be an effective teacher, whether it’s your first year or your 30th, the best thing you can do for yourself is to let go of the idea of “normal.” Offer all students the opportunity to grow from where they are, not from where your teacher training courses say they should be. You will not harm a student by offering him/her opportunities to complete work that is more advanced. Research consistently shows that curriculum based on development and ability is far more effective than curriculum based on age. A large body of research indicates that giftedness occurs along a continuum. As a teacher, you will likely encounter students who are moderately gifted, highly gifted and, perhaps if you’re lucky, even a few who are profoundly gifted. Strategies that work for one group of gifted students won’t necessarily work for all gifted students. Don’t be afraid to think outside the box. You’re in the business of helping students to develop their abilities. Just as athletes are good at athletics, gifted students are good at thinking. We would never dream of holding back a promising athlete, so don’t be afraid to encourage your “thinketes” by providing them with opportunities to soar.

-

Conduct Informal Assessments

Meeting the needs of gifted students does not need to be an all consuming task. One of the easiest ways to better understand how to provide challenging material is to conduct informal whole class assessments on a regular basis. For example, before beginning any unit, administer the end of the unit test. Students who score above 80 percent should not be forced to “relearn” information they already know. Rather, these students should be given parallel opportunities that are challenging. Consider offering these students the option to complete an independent project on the topic or to substitute another experience that would meet the objectives of the assignment, i.e. taking a college/distance course. With areas of the curriculum that are sequential, such as mathematics and spelling, how about giving the end of the year test during the first week of school. If you have students who can demonstrate competency at 80 percent or higher, you will save them an entire year of frustration and boredom if you can determine exactly what their ability level is and then offer them curriculum that allows them to move forward. Formal assessments can be extremely helpful, however, they are expensive and there is generally a back log of students waiting to be tested. Conducting informal assessments is a useful and inexpensive tool that will offer a lot of information.

-

Re-Familiarize Yourself with Piaget & Bloom

There are many developmental theorists and it is likely that you will encounter many of them during your teacher preparation course work. When it comes to teaching gifted children, take a few moments to review the work of Jean Piaget and Benjamin Bloom. Jean Piaget offers a helpful description of developmental stages as they relate to learning. Gifted students are often in his “formal operations” stage when their peers are still in his “pre-operational” or “concrete operations” stages. When a child is developmentally advanced he/she has different learning abilities and needs. This is where Bloom’s Taxonomy can be a particularly useful. Students in the “formal operations” developmental stage need learning experiences at the upper end of Bloom’s Taxonomy. Essentially all assignments should offer the student the opportunity to utilize higher level thinking skills like analysis, synthesis and evaluation, as defined by Bloom.

5: Involve Parents as Resource Locators

Parents of gifted children are often active advocates for their children. If you are not prepared for this, it can be a bit unnerving. The good news is that, at least in my experience, what they want most is to be heard and to encounter someone who is willing to think differently. Offer to collaborate with them, rather than resist them, to work together to see that their child’s needs are met. For example, if they want their child to have more challenging experiences in math, enlist their help in finding better curriculum options. An informal assessment can help them determine the best place to start and then encourage them to explore other options that could be adapted to the classroom. Most parents understand that teachers don’t have the luxury of creating a customized curriculum for every student, but most teachers are willing to make accommodations if parents can do the necessary research. Flexibility and a willingness to think differently can create win-win situations.

6: There is much more!

There are many more strategies that can assist advanced learners along their learning paths. See https://www.davidsongifted.org/gifted-blog/tips-for-teachers-successful-strategies-for-teaching-gifted-learners/ for more detailed information.

Emerging Bilinguals

Emerging Bilinguals (EBs) are the fastest-growing group of students in U.S. schools: in 2018, they comprised 10.2% of learners, totaling over five million students (NCES, 2020). Most teachers can now expect to have EBs in their classrooms at some point in their teaching careers. The majority of our EBs know Spanish as their first language, but there are many different languages that EBs know as their first languages, including Korean, Arabic, Urdu, Vietnamese, Japanese, French, as well as less common regional languages, such as those from various African countries.

Emerging Bilinguals have gone by many acronyms over the years. Some of the most common acronyms were Limited English Proficient (LEP), English as Second Language students (ESLs), English Language Learners (ELLs), and English Learners (ELs). In recent years, many scholars and educators (the editors of this book included) have stepped away from deficit terms such as LEP, ESL, ELL, and EL and adopted the term Emerging Bilinguals to emphasize the strength of these student-population.

Programs that service EBs in schools are most often referred to as ESL programs (English as a Second Language programs) or ESOL programs (English for Speakers of Other Languages programs). These programs are generally taught by licensed ESL teachers who specialize in language learning. Most ESL/ESOL programs are “pull-out” programs where small groups of students work with the ESL teacher during certain parts of the day, depending on student and ESL teacher schedules. In these pull-out programs, ESL teachers are working with students on their English skills, while at the same time often assisting classroom teachers with frontloading academic content. This means that the ESL teachers find out what content areas the classroom teachers will be focusing on next, and they work with their ESL students to prepare them for the academic English demands of that content.

Most EBs are assessed using ACCESS testing, which is based on the WIDA (World Class Instructional Design and Assessment) standards used across most states. The WIDA standards[1] were developed to assess EBs’ English language skills. These are not content standards, such as the ones discussed in previous chapters. The WIDA standards were developed in response to the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, which required English Language Proficiency standards to be linked with grade-level content standards and be rooted in what is called “academic language,” often referred to as the language of schooling. Some states developed their own proficiency standards, such as Massachusetts, but some states decided to work together to create standards that could be used across state lines. The standards this consortium of states developed are the WIDA standards. Forty one states have adopted these standards, which helps with collecting data on their effectiveness, in addition to making it easier to determine an EL’s language proficiency level if they move schools within a state or across states.

It is important to understand that the ACCESS testing measures language proficiency. The testing is not used to determine whether or not an EB has a learning disability. It can be challenging for teachers to differentiate between a language issue and a learning issue. A general rule to follow is that if the issue is manifesting itself in the student’s first language, such as a delay in understanding the sound/symbol relationship in phonics, then it is likely a learning issue. However, because letters make different sounds in different languages, this could also be a language issue. The best course of action is to seek assistance from colleagues (such as your school’s ESL teachers or special education teachers) if you, as the classroom teacher, feel that your EB student is not making typical academic progress.

In the following section, we will discuss in more detail students who do have special needs.

Students with Disabilities

Upon entering any U.S. public school today, you will likely see evidence that learners with disabilities are present and included. You might see a student using a wheelchair or talking with peers using a voice output communication device. You might see adapted swings on the playground or calming sensory rooms as you walk down the halls. You might see students and staff creating sidewalk art on April 2 to advocate for autism acceptance or wearing wild socks on March 21 to raise awareness about Down Syndrome.

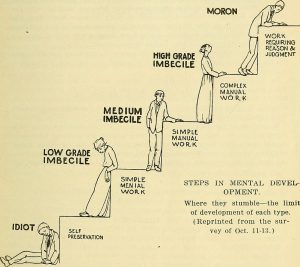

These signs of inclusion weren’t always present. In fact, the history of education in the United States is marked by practices that excluded, segregated, and marginalized people with disabilities based on the presumption that they were incompetent or incapable of benefitting from instruction. This presumption is demonstrated in this illustration, which depicts the expected limits of development for individuals with disabilities as described in a report to the Virginia General Assembly in 1915 (Virginia State Board of Charities and Corrections, 1915).

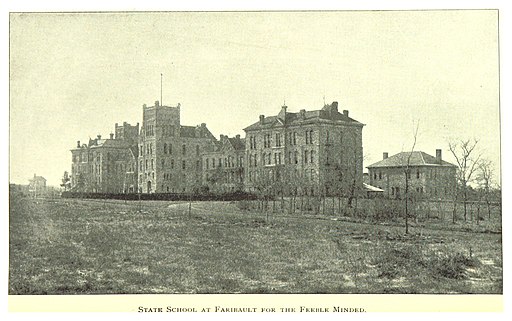

Because they were viewed as incapable and incompetent, individuals with clearly identifiable disabilities, such as significant intellectual disabilities or visible physical impairments, were often placed in institutions and residential facilities away from their families and communities well into the 20th century. This practice was described as a charitable and responsible way for society to protect them. This photograph depicts one such institution (Minnesota, 1893). This site was originally opened as the Minnesota Institute for Defectives in 1887 and was officially renamed the School for the Feeble-Minded in 1895 (Minnesota History Center, 2020). These images and the terms used in them are representative of practices and beliefs that existed to some degree well into the 20th century.

CRITICAL LENS: INSULTING LANGUAGE

When you look at some of the language used in the image above, you might see some overlaps with language used as insults (like calling someone an “idiot” or a “moron”). It is important to realize that these terms do have a long history of referring to people with special needs in negative ways. Learn more about which words have insulting histories[2], and check yourself when you use terms like “idiot,” “moron,” or “crazy” in your daily conversations. Watch this video to learn more about the “r word” and why it should be eliminated from your daily discourse.

Exclusionary practices continued into the 1970s when 1.75 million school-age children with disabilities were fully excluded from public schools and an additional three million children were placed in educational settings that did not meet their needs (Yell, 2019). These practices began to change in 1975 when the Education for All Handicapped Children Act (EAHCA) was passed. This law established a foundational set of protections for individuals with disabilities in U.S. public schools, which have since been expanded upon. These protections included the right to (a) a free education for all students between the ages of 3 and 18, (b) education in community schools when appropriate, (c) non-discriminatory evaluation to identify educational needs, (d) parent involvement in decision making, and (e) an individualized learning plan that defines appropriate goals and supports for each student with a disability (Yell, 2019).

Today, the educational rights of students with disabilities are protected by three major laws. These are Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act (1973), the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act (2004; a reauthorization of EAHCA), and the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA, 1990). These laws differ in how they define disability and in how they provide supports and protections.

Serving Students with Disabilities in the General Education Classroom

Teachers of all levels and subjects should expect to work with students who have disabilities. Data from the 2018 – 2019 school year show that 7.1 million students, approximately 14% of the total school-age population, receive special education under the IDEIA. Of those students, 82% spend at least 40% of their school day in a general education classroom (Institute of Education Sciences, 2020). Essentially, this means that most students who have disabilities are taught in the same setting and by the same teachers as learners who don’t have disabilities for large portions of the school day. Therefore, all teachers must be prepared to educate these students.

It is important for teachers to realize that special education is a service, not a place. This means that services including specialized instruction, accommodations, and modifications that address student needs can be provided in any setting and school teams are required to ensure that this happens in the Least Restrictive Environment (LRE). Both the IDEIA and Section 504 establish the general education classroom as the first consideration for LRE. Teams may only consider more restrictive settings, such as separate special education classrooms, when specialized supports added to the general education classroom are ineffective at meeting student needs.

In addition to supporting students with identified disabilities under IDEIA or Section 504, educators will also serve students whose disabilities may be unidentified. Because so many factors influence student development and learning, as discussed earlier in this chapter, it is critical that educators thoughtfully and systematically distinguish learning challenges caused by disabilities from learning challenges caused by social and environmental factors. When concerns develop about a student’s learning, general education teachers are expected to provide research-based interventions in an attempt to meet student needs and to collect progress monitoring data to support educational decision making. The RtI process is beneficial in that all students who demonstrate learning difficulties are systematically supported, regardless of whether they ultimately qualify for special education. Further, Response to Intervention (RTI) models have been shown to reduce misclassification of students with disabilities.

While teachers may feel challenged to meet the diverse and complex needs of students with disabilities in the general education classroom, the outcomes can be rewarding for students and teachers, alike. Benefits for students with disabilities include academic gains, improved social skills, and increased friendships (e.g., Wehmeyer et al., 2020). Peers who do not have disabilities have been shown to have deeper understandings of themselves, positive expectations of interactions with people with disabilities, and, in cases where peers act in support roles, greater academic engagement (e.g., Carter et al., 2015). Additionally, general education teachers have reported feeling more aware of and more effective at meeting the needs of all students after working with students with disabilities (Finke et al., 2009). These positive outcomes are linked to the use of strategies that provide a broad range of support for all students.

Passed in 1973 to prohibit discrimination based on disability. Includes Section 504.

Specific section of the 1973 Rehabilitation Act that forbids organizations (including schools) from excluding or denying services to individuals with disabilities. Individual student accommodations are documented in personalized 504 plans.

Pronounced "idea"; 2004 reauthorization of the Education for All Handicapped Children Act (EAHCA) that defines 14 specific disability categories. Also called IDEA.

Stipulation of IDEiA that students with special needs must receive specially designed instruction, including special education and accommodations, that allows them to make meaningful progress toward the curriculum and their individual learning goals. All of these services must be provided at public expense.

Unique learning plan for students with disabilities developed annually by a team that includes general and special education teachers, administrators, the student’s parents, and the student (when age-appropriate).

Expectation that students with disabilities must be educated in the same setting as their peers who do not have disabilities, unless it is not possible for the student to make progress in that setting even when additional supports are added.

Abbreviation for English as a Second Language programs.

Abbreviation for English for Speakers of Other Languages programs.

Instructional approach that involves pre-teaching background knowledge or vocabulary necessary for upcoming instruction. Particularly helpful for ELs.

Consortium that designed standards for and assessments of assess English language skills for ELs.

Standards-based reform passed in 2001 as a reauthorization of the 1965 Elementary and Secondary Education Act. Increased educational accountability through standardized testing.

1975 legislation that established a foundational set of protections for individuals with disabilities in U.S. public schools, including (a) a free education for all students between the ages of 3 and 18, (b) education in community schools when appropriate, (c) non-discriminatory evaluation to identify educational needs, (d) parent involvement in decision making, and (3) an individualized learning plan.