5

As a student, you may have enjoyed going to school with friends who lived in your neighborhood. But did you know that where you live also can impact how well-funded and well-resourced your school is? Because schools get much of their funding from property taxes, areas with more expensive houses have higher taxes, resulting in more school funding. While the United States believes education should be accessible to all, where you live can determine which resources will or will not be available to benefit your learning.

This chapter describes models of schools present in the United States today, including their funding, enrollment policies, and key characteristics. Different models of schools, varying configurations of classrooms and instructional models are presented and the variety of schools in the United States offers some families the option of school choice, including charter schools and vouchers.

Chapter Outline

Models of Schools

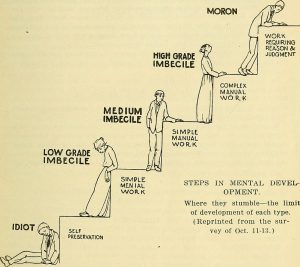

One central tenet of the U.S. education system is that all people in our country deserve access to education, regardless of the language you speak, how much money you make, where you live, or the color of your skin. Some other countries employ tracking, which means that certain individuals are channeled into certain educational “tracks” based on their perceived capabilities for future success. Tracking limits access to education for certain groups of people. In the United States, all children and youth have access to K-12 educational opportunities.

CRITICAL LENS BOX: TRACKING

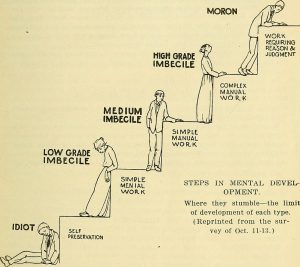

While the U.S. does not “track” students in the ways some other countries do, we do still engage in some forms of tracking. For example, you may have heard of–or even experienced–ability grouping. This term refers to placing students in homogeneous groups by ability levels. In secondary school, tracking may result in college prep, honors, or AP-level courses. Historically, these different curricula were developed when more Black and working-class students were entering schools, and elite educational opportunities were reserved for upper-middle-class students, who were often White, wanting to attend college (Education Week, 2004). Therefore, tracking “quickly took on the appearance of internal segregation” (para. 2), which is a problem since racial discrimination in education is illegal. So, while U.S. educational systems do not force a student into a specific educational track for a specific career at an early age like some countries do, tracking by ability level is still a harmful practice in many U.S. schools. Teachers need to be aware of potential biases toward students in certain tracked groups (i.e., AP students are “good” and college prep students are “bad”).

The majority of schools in the United States fall into one of two categories: public or private. A public school is defined as any school that is maintained through public funds to educate children living in that community or district for free. The structure and governance of a public school varies by model, but shares the characteristics of being free and open to all applicants within a defined boundary. A private school is defined as a school that is privately funded and maintained by a private group or organization, not the government, usually by charging tuition. Private schools may follow a philosophy or viewpoint different from public schools; for example, many private schools are governed by religious institutions.

There are a variety of public school models, including traditional, charter, magnet, Montessori, virtual, alternative, and language immersion. Private school models include traditional, religious, parochial, Montessori, Waldorf, virtual, boarding, and international schools. Some school models may be public or private. Table 4.1 includes a breakdown of school models, their funding source, and key characteristics.

Table 5.1: School Models by Funding, Enrollment, and Key Characteristics

| School Model | Public or Private | Enrollment | Key Characteristics |

| Traditional Public | Public | Open/School Boundary Lines | State and local governance, policy and curriculum. |

| Magnet | Public | Open across school district/Application or lottery | Specializes in program (art, science, math, etc), promotes diversity across a district. |

| Alternative | Public | Students that cannot attend traditional school due to a variety of factors. | State and local governance, policy and curriculum. Small class sizes and alternative scheduling. Individualized support. |

| Language Immersion/ Bilingual | Both | Open across school district/Application | A portion of instruction is taught in a language other than English. Students are immersed in a second language for part of instruction. |

| Charter | Both | Open across school district/Application or lottery | Autonomous from local and state authority as long as the school meets charter mission and performance measures. |

| Montessori | Both | Open across school district/Application | Philosophy that children need connection to the environment. Focuses on real life experiences. |

| Waldorf | Private | Application/Tuition | Believes each child has unique potential that should be developed through education to better humanity as a whole. While not specifically religious, Waldorf schools are based on general spirituality. Focuses on imagination and fantasy. |

| Virtual | Both | Open across school district/Application | The majority of instruction is provided in an online environment. |

| Traditional Private | Private | Application/Tuition | Curriculum decided upon by the governing body (board, organization, or company). May be non-profit or for profit. |

| Religious | Private | Application/Tuition | Mission is to teach religious values in addition to teaching core curriculum. |

| Parochial | Private | Application/Tuition | Mission is to teach religious values in addition to teaching core curriculum. School is sponsored by a local church through funding. |

| Boarding | Private | Application/Tuition | Community of scholars, artists, and athletes. School provides food and housing. |

| International | Private | Application/Tuition | Follows a curriculum different from that of the country in which the school is physically located. May use International Baccalaureate curriculum, among others. Students consist of a diverse population that is often highly mobile. |

| Department of Defense Education Activity (DoDEA) | Public | Serves military and Department of Defense dependents serving overseas and in the U.S. U.S. contractor dependents may attend for a fee. | Follows a standard curriculum across schools. Makes up the 10th largest school district in the U.S. Consists of two parallel districts: Department of Defense Dependents Schools (DoDDS) operating in Europe and the Pacific and Department of Defense Domestic Dependent Elementary and Secondary Schools operating in the Americas. |

One type of school not listed in the table is homeschool. Homeschooling is a type of schooling that would not fall into either the public or private category. Homeschooling is defined as a child not enrolling in a public or private school, but receiving an education at home. Each state has its own rules and regulations that families must follow and report on if homeschooling. For example, the Virginia Department of Education (2021) requires that families inform the school division of their decision to homeschool their child, update the school district with the student’s annual academic progress, and provide evidence that the homeschool instructor (such as a parent) meets specific qualifications to fill the role. For information about homeschooling in Tennessee, follow this link: https://www.tn.gov/education/school-options/home-schooling-in-tn.html

Enrollment Policies

In addition to the schools being separated by their funding source, schools are defined by their process of enrollment. The majority of public schools operate on two basic enrollment guidelines: boundary or open. Districts with enrollment policies using school boundary lines allow all students within a geographic area to enroll in the school. If a school has an open enrollment policy, then the school will also allow students from other geographic areas within the district to enroll if space permits. School boundary lines are often highly politicized. Schools are publicly rated and this affects everything from property values to the quality of teachers recruited. Ratings may be based on data sources like the school report card, which may include data on teacher education levels, teacher retention, student demographics, student performance on standardized tests, and student and teacher attendance rates. However, ratings also can be culturally biased: one nonprofit rating site called GreatSchools ( https://www..org/ ) , which often is integrated into online realtor websites as families are choosing where to move, redid their rating formula in 2017 after it realized that their previous rating system prioritized schools in predominantly White neighborhoods (Barnum & LeMee, 2019).

Critical Lens: Redlining

Although the Supreme Court made segregated schools illegal in Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, you will see many schools today that continue to have student populations that are separated by race or socioeconomic status. This trend is due to a practice called redlining, in which housing was allowed or denied in certain areas based on people’s race or socioeconomic status. The impacts of redlining are ongoing de facto segregation, which means that while overt segregation was outlawed, it still continues in other ways.

Some public school models, including charter, magnet, and language immersion, may have more students desiring to apply than there is space. In these schools, applications or lotteries may be used. An application system allows the schools to choose students based on characteristics, such as grades, demographic diversity, or geographic area. Often these schools are looking for high-achieving students or have a mission of diversifying the school. A lottery system gives each student that has applied an equal chance of attending and is decided by randomly selecting names from the pool of students.

Key Characteristics

Schools also differ in several key characteristics beyond funding and enrollment. One key characteristic of schools is what individuals or entities provide supervision or oversight of the school’s functioning. A school’s ability to follow curriculum (how instruction is organized and managed) and policies (such as rules, expectations, and norms that school community members must follow) is directly tied to their funding.

For the majority of public schools (excluding charter schools), state and local entities supervise curriculum and policies. In private schools, boards, organizations, or companies often supervise curriculum and policies. In addition, a school’s curriculum is often defined by its mission or philosophy. Schools may differ in how curriculum is presented or in specialized programs. For example, language immersion schools present standardized curriculum in two languages, while magnet schools place an emphasis on a certain part of the curriculum like science or art. Religious schools may focus on presenting curriculum based on a religious viewpoint or values.

Season 2: Episode 6 – A Reckoning OPTIONAL (Link to Podcast)

Season 2: Episode 6 – A Reckoning OPTIONAL (Link to Podcast)

Classroom/Instructional Models

Within each school a variety of classroom models may be utilized. Traditionally, schools have different grade levels with a different teacher for each grade. However, some schools may incorporate multi-age classrooms. Multi-age classrooms allow for students of different grades to be in one class. For example, students in second and third grade may be combined in one classroom. While this may seem difficult to manage, a traditional classroom model does not guarantee that all students with the same chronological age will be at the same developmental stage. Children develop at different rates and have different academic skill levels. Many multi-age classrooms recognize this and are able to provide both homogeneous and heterogeneous groupings in the classroom. When students are grouped homogeneously for small group lessons, a younger student may benefit from instruction at a higher level that they may not have had access to at their grade level. Heterogeneous grouping of students also provides peer modeling and support from more advanced students (Carter, 2005).

Many multi-age classrooms and traditional classroom models utilize co-teaching. Co-teaching is when teachers are paired up in a classroom and share the responsibility of planning, teaching, and assessing students. Having more than one teacher in a classroom provides additional support for students that need one-on-one instruction or additional supports. This is often seen in classrooms where special education or bilingual teachers are paired with a classroom teacher to make instruction for students with disabilities or English Language Learners more inclusive. Co-teaching also may elevate instruction by having two teachers plan together. The division of teaching responsibilities may present itself in a variety of ways, including the following: one teacher teaches and the other observes, one teaches and one drifts, teachers teach at stations, team teaching (both tag team at teaching same lesson), and parallel teaching (class is divided into two groups that receive the same instruction simultaneously) (Trites, 2017).

Sometimes an individual teacher may loop with their students. Looping occurs when a classroom teacher moves with a group of students from grade to grade. For example, a teacher may have a group of students for third grade, and then move with them to fourth grade. Early looping, or teacher cycling, has foundations in one-room schoolhouses. In the early 1900s, looping was also promoted in urban school districts as a way to improve relationships between students and teachers. Looping is also a key component of Waldorf schools. Looping may increase student-teacher relationships and family-teacher relationships, but it also may increase instructional time from year to year. When teachers loop with students, the classroom routines and structure remain the same, so valuable instructional time is not spent on teaching new routines and classroom structure. Teachers may also spend less time on initial assessment of students. Research has shown that when teachers loop, less retention and referral of students occurs (Grant, Richardson & Forsten, 2000). For looping to be successful, a teacher must feel comfortable teaching across grade levels and be seen as effective. If a teacher is ineffective, then students looping would be at a disadvantage. A teacher wanting to loop may also have difficulty doing so if it is not common in their school or district. Many teachers only teach one grade, but if a third-grade teacher loops to fourth grade, it means a fourth-grade teacher at the school must also be willing to leave that grade level.

Different classroom and teaching models vary from school to school and district to district. Multi-age classrooms, co-teaching, and looping may be implemented by choice, or as a way to consolidate or expand resources. For example, multi-age classrooms may help schools save space when classroom space is limited within the physical school. These practices may also help students when academic or developmental needs are highly diverse. If a school has a large percentage of children that are academically diverse, then dividing them by chronological age may not be appropriate. These decisions are often made at the school level by the principal.

With so many school models available in the U.S., how do families choose which type of school their child should attend? School choice is a complex issue for families to navigate. What may be best for one student is not always best for another. The choices for students also vary by geographic and socioeconomic boundaries. Many families make school decisions based on the following factors:

- transportation and distance to chosen school;

- cost or tuition of school;

- curriculum and programs available;

- religious affiliation; and

- fit for the individual student.

Families in some areas of the U.S. have greater access to the different models of schools. Small rural towns may only have one school within the immediate area. However, federal reform policies, such as No Child Left Behind (NCLB), have increased the number of charter schools and use of vouchers.

School Choice

With so many school models available in the U.S., how do families choose which type of school their child should attend? is a complex issue for families to navigate. What may be best for one student is not always best for another. The choices for students also vary by geographic and socioeconomic boundaries. Many families make school decisions based on the following factors:

- transportation and distance to chosen school;

- cost or tuition of school;

- curriculum and programs available;

- religious affiliation; and

- fit for the individual student.

Families in some areas of the U.S. also have greater access to the different models of schools presented at the beginning of this chapter than others. Small rural towns may only have one school within the immediate area. However, federal reform policies, such as No Child Left Behind (NCLB), have increased the number of charter schools and use of vouchers.

Charter Schools

In 2001, when NCLB was signed into law, federal and state funds required schools to make an Annual Yearly Progress (AYP) report, based on assessment data. Schools that did not meet AYP for two consecutive years were often required to earmark money for student tutoring or allow students to transfer. When a student transfers, the school’s funding formula decreases by one student, resulting in a loss of funds for the school. If a school continues to not meet AYP, then the school may be closed. When a school is closed, it often becomes a charter school (Brookhart, 2013).

As shown earlier in Table 4.1, charter schools are often publicly funded, but they do not have the same requirements as a traditional public school. When a student transfers out of a traditional school to a charter school, the funds follow the student. Charter schools are autonomous from public schools and to operate must meet the educational goals set forth in their charter. Charter school admittance is also application based, usually being first come, first served or by lottery. In 2010, charter schools comprised six percent of public school students, but now the number is closer to 30 percent in some localities (Prothero, 2018).

Why does it matter if public schools become charter schools? In many regions, like Minneapolis-St. Paul, California, and Texas, charter schools are more segregated than the public schools within those same boundaries, which were already highly segregated (Institute on Race and Poverty, 2008). Because charter schools rely on applications for admission, parent participation in the admission process also separates students by socioeconomics (Frankenberg et al., 2011).

Vouchers

One reason that school choice has become so politicized is the use of school vouchers. School vouchers are defined as “a government-supplied coupon that is used to offset tuition at an eligible private school” (Epple et al., 2017, p. 441). In the 1960s, some of the first school vouchers were awarded to promote desegregation. School voucher policies and programs today vary across localities and are present in over thirty states. Students who receive vouchers enroll in a private school, which receives those funds. The voucher may cover tuition in full, or offset it significantly. This video explains some of the pros and cons of vouchers.

Voucher Funding

Vouchers are funded by one of the following: tax revenues, tax credits, or by private organizations (Epple et al., 2017). The majority of states that use tax revenues to fund their vouchers provide vouchers to under-resourced students. For example, Milwaukee, Cleveland, New Orleans, and Washington, DC provide vouchers to students whose family income is just above the poverty line. Some areas, such as in Ohio and Indiana, provide vouchers using tax revenues to all students in failing school districts.

Some states (including Florida, Iowa, Georgia, Indiana, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, and Rhode Island) utilize tax credits to fund vouchers. Businesses in these states that fund vouchers are provided a tax credit. For example, Florida businesses can receive 100 percent corporate tax income credit up to $559.1 million dollars (EdChoice, 2019). In addition to tax revenues and tax credits, many states also have privately funded voucher programs. One notable voucher program is the Children’s Scholarship Fund, which was founded with contributions from the Walton Family Foundation (Epple et al., 2017).

Voucher Outcomes

When a student uses a voucher to attend a private school, this changes the funding formulas for a local school. This student is no longer included in the funding formula for the LEA or SEA. This means that the local and state budget is lowered because one less student is being counted in that funding formula. School vouchers are provided and promoted to give under-resourced students school choice, but not all students have equal opportunities.

Public schools allow and are required by law to provide services for all students. While policies prohibit private schools from discriminating against students based on race, many religious private schools may consider religious affiliation, sexual orientation (except Maryland, which has laws prohibiting private schools utilizing vouchers to do so), and disability in their admission decisions. Private schools are not exempt from discrimination laws, but the application process allows them to choose which students to admit. For example, a private school receiving government funds must provide students with disabilities with accommodations, unless these accommodations change the philosophy of the academic program, or create “significant difficulty or expense.” A large portion of private schools do not hire teachers trained to provide accommodations; thus, many claim they do not have the resources to serve students with disabilities. Vouchers are not beneficial for students with disabilities that cannot attend private schools, but vouchers also hinder these students further by diverting funds from the public schools, who do provide these services, when other students use vouchers.

Conclusion

While many individuals and groups call for school reform in order to provide equity to all students, the process is complex. School choice and the varied school models within the U.S. also makes school reform highly political. While families are given the right to choose their own child’s education, many families’ choices are constrained by geographic and economic resources. The landscape of schools in the U.S. is constantly changing, but one principle will remain as the foundation of schools in this country: everyone deserves access to education.

In this section, we will explore philosophical foundations of education in the United States.

Chapter Outline

Philosophical Foundations

As students ourselves, we may have a particular notion of what schooling is and should be as well as what teachers do and should do. In his book entitled Schoolteacher: A Sociological Study, Dan Lortie (1975) called this the “apprenticeship of observation” (p. 62). Many people who pursue teaching think they already know what it entails because they have generally spent at least 13 years observing teachers as they work. The role of a teacher can seem simplistic because as a student, you only see one piece of what teachers actually do day in and day out. This can contribute to a person’s idea of what the role of teachers in schools is, as well as what the purpose of schooling should be. The idea of the purpose of schooling can also be seen as a person’s philosophy of schooling.

Philosophy can be defined as the fundamental nature of knowledge, reality and existence. In the case of education, one’s philosophy is what one believes to be true about the essentials of education. When thinking about your philosophy of education, consider your beliefs about the roles of schools, teachers, learners, families, and communities. Four overall philosophies of education that align with varying beliefs include perennialism, essentialism, progressivism, and social reconstructionism, which are summarized in Table 3.1.

Table 3.1: Four Key Educational Philosophies

| Educational Philosophy | Purposes & Beliefs |

| Perennialism | Focus on the great ideas of Western civilization, viewed as of enduring value. Focus on developing intellect and cultural literacy. Also called a classical curriculum. |

| Essentialism | Focus on teaching a common core of knowledge, including basic literacy and morality. Believes schools should not try to critique or change society, but rather transmit essential understandings. |

| Progressivism | Focus on the whole child as the experimenter and independent thinker. Believes active experience leads to questioning and problem solving. Approaches textbooks as tools instead of authoritarian sources of knowledge. |

| Social Reconstructionism | Focus on developing important social questions by critically examining society. Recognizes influence of social, economic, and political systems. Believes schools can lead to collaborative change to develop a better society and enhance social justice. |

Perennialism

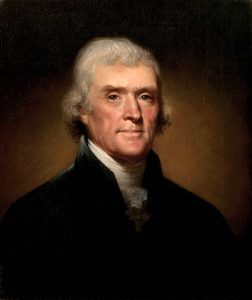

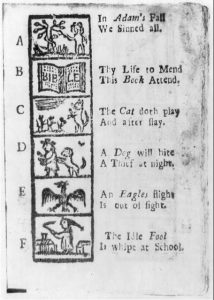

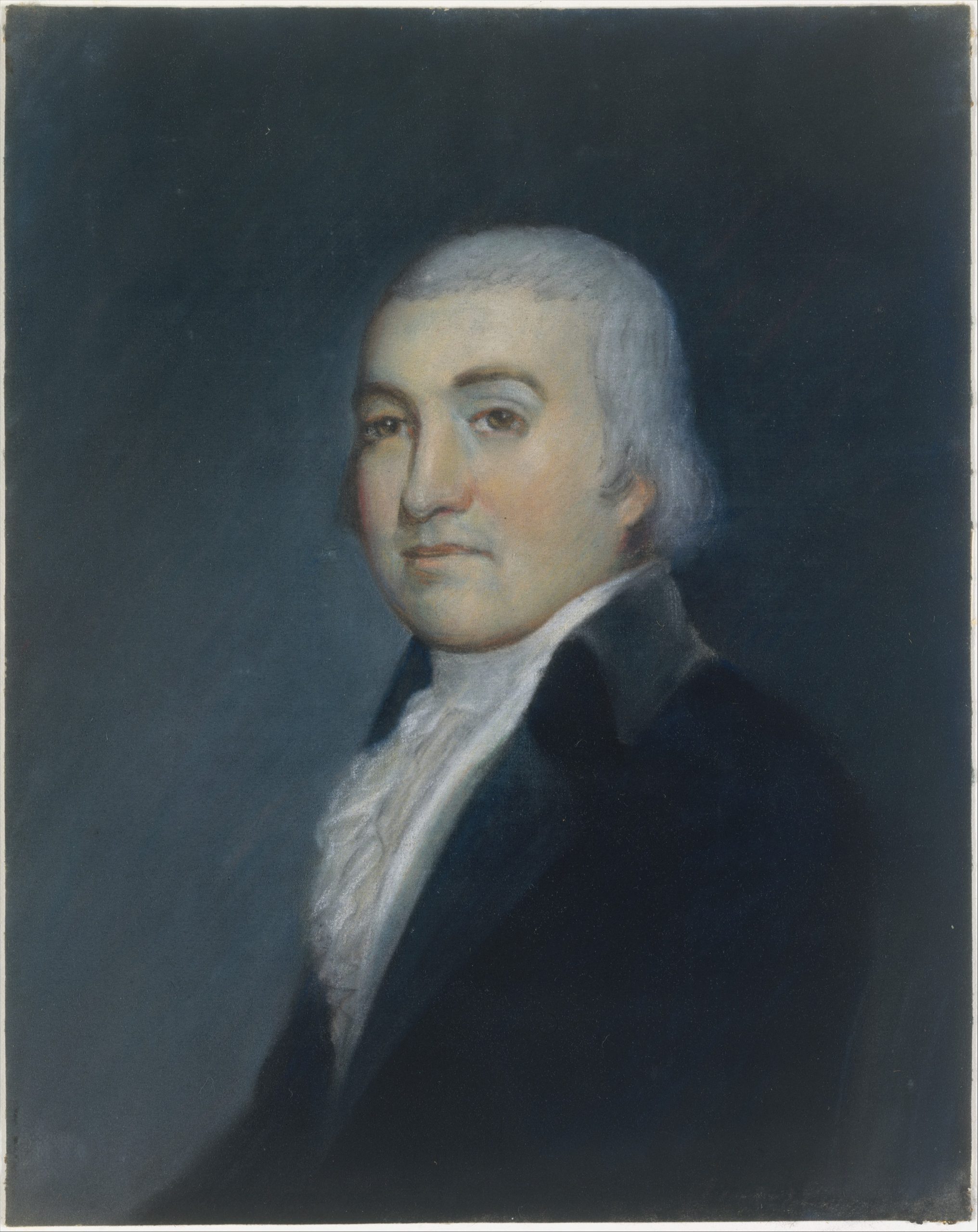

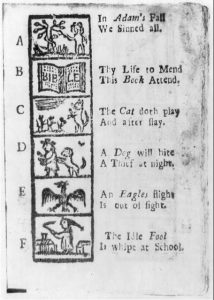

Perennialism is an educational philosophy suggesting that human nature is constant, and that the focus of education should be on teaching concepts that remain true over time. School serves the purpose of preparing students intellectually, and the curriculum is based on “great ideas” that have endured through history. See the following video for additional explanation.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P9V_50IVbng

Essentialism

Essentialism is an educational philosophy that suggests that there are skills and knowledge that all people should possess. Essentialists do not share perennialists' views that there are universal truths that are discovered through the study of classic literature; rather, they emphasize knowledge and skills that are useful in today’s world. There is a focus on practical, useable knowledge and skills, and the curriculum for essentialists is more likely to change over time than is a curriculum based on a perennialist point of view. The following video explains the key ideas of essentialism, including the role of the teacher.

https://youtu.be/OScVwnxLrWE

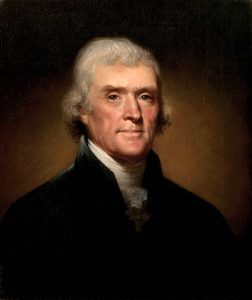

Progressivism

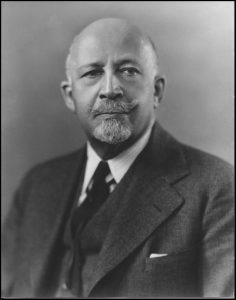

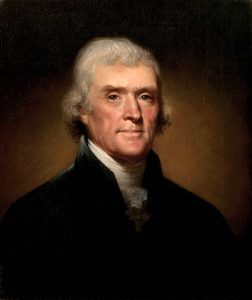

Progressivism emphasizes real-world problem solving and individual development. In this philosophy, teachers are more “guides on the sides” than the holders of knowledge to be transmitted to students. Progressivism is grounded in the work of John Dewey[1]. Progressivists advocate a student-centered curriculum focusing on inquiry and problem solving. The following video gives further explanation of the progressivist philosophy of learning and teaching.

https://youtu.be/6C6DUKx72_8

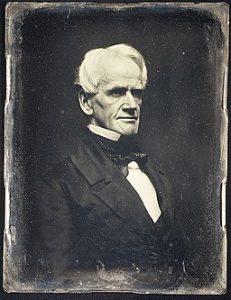

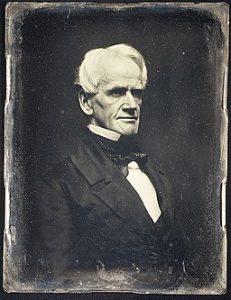

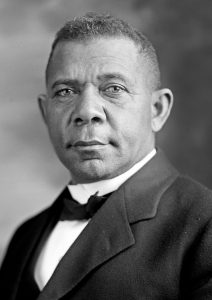

Social Reconstructionism

The final major educational philosophy is social reconstructionism. Social reconstructionism theory asserts that schools, teachers, and students should take the lead in addressing social problems and improving society. Social reconstructionists feel that schooling should be used to eliminate social inequities to create a more just society. Paulo Freire[2], a Brazilian philosopher and educator, was one of the most influential thinkers behind social reconstructionism. He criticized the banking model of education in his best known writing, Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Banking models of education view students as empty vessels to be filled by the teacher’s expertise, like a teacher putting “coins” of information into the students’ “piggy banks.” Instead, Freire supported problem-posing models of education that recognized the prior knowledge everyone has and can share with others. Conservative critics of social reconstructionists suggest that they have abandoned intellectual pursuits in education, whereas social reconstructionists believe that the analyzing of moral decisions leads to being good citizens in a democracy.

https://youtu.be/SAkdavC-lX8

Common educational philosophies including perennialism, essentialism, progressivism, and social reconstructionism reflect varying beliefs about the roles education should fill.

Like learning, teaching is always developing; it is never realized once and for all. Our public schools have always served as sites of moral, economic, political, religious and social conflict and assimilation into a narrowly defined standard image of what it means to be an American. According to Britzman (as quoted by Kelle, 1996), “the context of teaching is political, it is an ideological context that privileges the interests, values, and practices necessary to maintain the status quo.” Teaching is by no means “innocent of ideology,” she declares. Rather, the context of education tends to preserve “the institutional values of compliance to authority, social conformity, efficiency, standardization, competition, and the objectification of knowledge” (p. 66-67).

Season 2: Episode 8 - The Final Exam OPTIONAL (LINK TO PODCAST)

Conclusion

It should be no surprise then that contemporary debates over public education continue to reflect our deepest ideological differences. As Tyack and Cuban (1995) have noted in their historical study of school reform, the nation’s perception toward schooling often “shift[s]… from panacea to scapegoat” (p. 14). We would go a long way in solving academic achievement and closing educational gaps by addressing the broader structural issues that institutionalize and perpetuate poverty and inequality.

In this section, we will explore philosophical foundations of education in the United States.

Chapter Outline

Philosophical Foundations

As students ourselves, we may have a particular notion of what schooling is and should be as well as what teachers do and should do. In his book entitled Schoolteacher: A Sociological Study, Dan Lortie (1975) called this the “apprenticeship of observation” (p. 62). Many people who pursue teaching think they already know what it entails because they have generally spent at least 13 years observing teachers as they work. The role of a teacher can seem simplistic because as a student, you only see one piece of what teachers actually do day in and day out. This can contribute to a person’s idea of what the role of teachers in schools is, as well as what the purpose of schooling should be. The idea of the purpose of schooling can also be seen as a person’s philosophy of schooling.

Philosophy can be defined as the fundamental nature of knowledge, reality and existence. In the case of education, one’s philosophy is what one believes to be true about the essentials of education. When thinking about your philosophy of education, consider your beliefs about the roles of schools, teachers, learners, families, and communities. Four overall philosophies of education that align with varying beliefs include perennialism, essentialism, progressivism, and social reconstructionism, which are summarized in Table 3.1.

Table 3.1: Four Key Educational Philosophies

| Educational Philosophy | Purposes & Beliefs |

| Perennialism | Focus on the great ideas of Western civilization, viewed as of enduring value. Focus on developing intellect and cultural literacy. Also called a classical curriculum. |

| Essentialism | Focus on teaching a common core of knowledge, including basic literacy and morality. Believes schools should not try to critique or change society, but rather transmit essential understandings. |

| Progressivism | Focus on the whole child as the experimenter and independent thinker. Believes active experience leads to questioning and problem solving. Approaches textbooks as tools instead of authoritarian sources of knowledge. |

| Social Reconstructionism | Focus on developing important social questions by critically examining society. Recognizes influence of social, economic, and political systems. Believes schools can lead to collaborative change to develop a better society and enhance social justice. |

Perennialism

Perennialism is an educational philosophy suggesting that human nature is constant, and that the focus of education should be on teaching concepts that remain true over time. School serves the purpose of preparing students intellectually, and the curriculum is based on “great ideas” that have endured through history. See the following video for additional explanation.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P9V_50IVbng

Essentialism

Essentialism is an educational philosophy that suggests that there are skills and knowledge that all people should possess. Essentialists do not share perennialists' views that there are universal truths that are discovered through the study of classic literature; rather, they emphasize knowledge and skills that are useful in today’s world. There is a focus on practical, useable knowledge and skills, and the curriculum for essentialists is more likely to change over time than is a curriculum based on a perennialist point of view. The following video explains the key ideas of essentialism, including the role of the teacher.

https://youtu.be/OScVwnxLrWE

Progressivism

Progressivism emphasizes real-world problem solving and individual development. In this philosophy, teachers are more “guides on the sides” than the holders of knowledge to be transmitted to students. Progressivism is grounded in the work of John Dewey[3]. Progressivists advocate a student-centered curriculum focusing on inquiry and problem solving. The following video gives further explanation of the progressivist philosophy of learning and teaching.

https://youtu.be/6C6DUKx72_8

Social Reconstructionism

The final major educational philosophy is social reconstructionism. Social reconstructionism theory asserts that schools, teachers, and students should take the lead in addressing social problems and improving society. Social reconstructionists feel that schooling should be used to eliminate social inequities to create a more just society. Paulo Freire[4], a Brazilian philosopher and educator, was one of the most influential thinkers behind social reconstructionism. He criticized the banking model of education in his best known writing, Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Banking models of education view students as empty vessels to be filled by the teacher’s expertise, like a teacher putting “coins” of information into the students’ “piggy banks.” Instead, Freire supported problem-posing models of education that recognized the prior knowledge everyone has and can share with others. Conservative critics of social reconstructionists suggest that they have abandoned intellectual pursuits in education, whereas social reconstructionists believe that the analyzing of moral decisions leads to being good citizens in a democracy.

https://youtu.be/SAkdavC-lX8

Common educational philosophies including perennialism, essentialism, progressivism, and social reconstructionism reflect varying beliefs about the roles education should fill.

Like learning, teaching is always developing; it is never realized once and for all. Our public schools have always served as sites of moral, economic, political, religious and social conflict and assimilation into a narrowly defined standard image of what it means to be an American. According to Britzman (as quoted by Kelle, 1996), “the context of teaching is political, it is an ideological context that privileges the interests, values, and practices necessary to maintain the status quo.” Teaching is by no means “innocent of ideology,” she declares. Rather, the context of education tends to preserve “the institutional values of compliance to authority, social conformity, efficiency, standardization, competition, and the objectification of knowledge” (p. 66-67).

Season 2: Episode 8 - The Final Exam OPTIONAL (LINK TO PODCAST)

Conclusion

It should be no surprise then that contemporary debates over public education continue to reflect our deepest ideological differences. As Tyack and Cuban (1995) have noted in their historical study of school reform, the nation’s perception toward schooling often “shift[s]… from panacea to scapegoat” (p. 14). We would go a long way in solving academic achievement and closing educational gaps by addressing the broader structural issues that institutionalize and perpetuate poverty and inequality.

“He is just so lazy - sits there and refuses to do any work. And his parents are no help - they never return phone calls or emails. Why bother?”

This is an actual statement by a teacher frustrated with a fourth grader in her classroom. What this teacher did not know was the context in which the student was living. He was homeless and living out of his mother’s car. His mother couldn’t pay her cell phone bill, so had no way of receiving phone calls or emails. The teacher failed to realize what else could be contributing to his “laziness”: hunger, fear, lack of adequate care, and a parent unavailable to him with her own struggle to survive.

In order to teach our students, we have to know them. Multiple influences affect our students and their environments.

Chapter Outline

In this chapter, we will investigate how different systems influence learning and we will explore two theoretical perspectives on development.

Systems that Influence Student Learning

As humans grow and develop, there are many different systems that influence this development. Think about systems as interrelated parts of a whole, just like the solar system is made up of planets and other celestial objects. Two theories that consider various impacts on student learning are Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences.

Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs

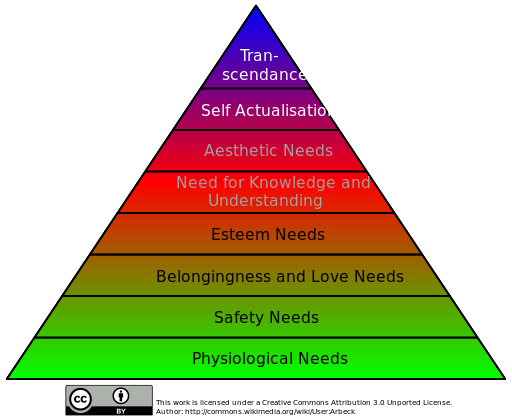

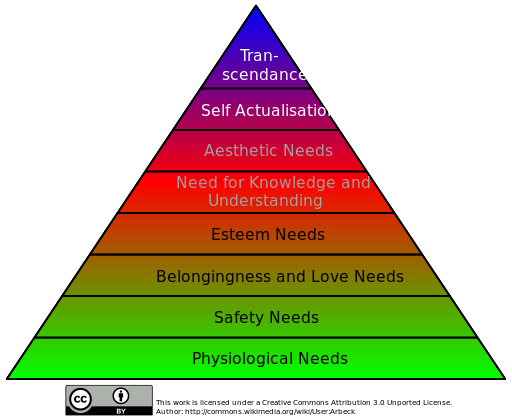

One way to conceptualize influences on student learning is through need systems. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (see Figure 2.2) theorized that people are motivated by a succession of hierarchical needs (McLeod, 2020). Originally, Maslow discussed five levels of needs shaped in the form of a pyramid. He later adjusted the pyramid to include eight levels of needs, incorporating need for knowledge and understanding, aesthetic needs, and transcendence. Figure 2.2 depicts these eight needs in hierarchical order. The first four levels are deficiency needs, and the upper four are growth needs. The first four are essential to a student’s well being, and they build on each other. These deficiency needs must be satisfied before a person can move on to the growth needs. Moving to the growth needs is essential for learning to truly occur. Now we will examine each of the elements within Maslow’s hierarchy of needs in more depth.

Of the eight levels, the first is physiological needs. These needs include food, water, and shelter. In this case, do students have a home where they are properly nourished? If not, students who are not attending to their work may be hungry, not just daydreaming. This is why free and reduced breakfast and lunch programs are so essential in schools.

Safety and security needs are the second level of the pyramid. Students need to feel that they are not in harm’s way. Schools are responsible for maintaining safe environments for students and classrooms need to feel safe and secure. This requires classroom rules that all students follow, including protecting students from bullying and threatening behavior. There are effective and less effective ways to structure a classroom so that it is safe for all students.

The third level of Maslow’s hierarchy is love and belonging. In schools, these needs are met primarily through positive relationships with teachers and peers, and people with whom students regularly interact. Feelings of acceptance are necessary here, and teachers can play a huge role in creating these feelings for students. It is critical that teachers are non-judgmental towards their students. It does not matter how you, as a teacher, may feel about a student’s lifestyle choices, beliefs, political views or family structures; it matters how a student perceives you as someone who accepts them, no matter what.

The fourth and final level of deficiency needs is esteem needs: self-worth and self-esteem. Students must have experiences in schools and classrooms that lead them to feel positive about themselves. Self-esteem is what students think and feel about themselves, and it contributes to their confidence. Self-worth is students knowing that they are valuable and lovable.

Figure 2.2: Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs

Following the four deficiency needs in Maslow’s hierarchy are growth needs. Once students reach growth needs, they are ready for true, meaningful learning. The fifth element, the need to know and understand, is also referred to as cognitive needs. It is our job as educators to motivate students to want to know and understand the world around them. In order to do this, we must be sure we are providing our students with questions that move them to higher-order thinking skills. An instructional model that is well-developed and utilized in many classrooms is Bloom’s Taxonomy. It can be used to classify learning objectives, and it is a way to encourage students to think more deeply about content and motivate them to want to know more.

The sixth level of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is aesthetic needs. At this level, we can learn to appreciate the beauty of the natural world. When we are focused on deficiency needs in the lower levels of Maslow’s theory, it is more difficult to see the beauty in our environment and surroundings. In education, students need to be exposed to the beauty that is reflected in the arts: music, visual arts and theatre. Most schools separate these into distinct periods or blocks; however, it is essential that arts are also integrated into the curriculum. Additionally, students should be exposed to arts outside of Western art so they encounter art forms that include representations of all cultures, including their own.

Self-actualization is the seventh need on the pyramid and is another growth need. Maslow indicated that this happens as we age. It is our intrinsic need to make the most of our lives and reach our full potential. A way of thinking about this is to consider what we think of our ideal selves--or, for young people, how they see themselves or what they see themselves having achieved and broadly experienced as they get to later stages in life.

Finally, transcendence needs are the highest on Maslow’s hierarchy. Maslow (1971) stated, “transcendence refers to the very highest levels of human consciousness, behaving and relating, as ends rather than means, to oneself, to significant others, to human beings in general, to other species, to nature, and to the cosmos” (p. 269). Though most of us in K-12 schools will not experience students at this level, it is important to note that this is the goal in life, according to Maslow.

Critical Lens: Origins of Theories

Sometimes we hold theories as universal truths without stopping to consider the context in which they were made. For example, Bridgman, Cummings, and Ballard (2019) recently investigated the origin of Maslow's theory and discovered that he himself never created the well-known pyramid model to represent the hierarchy of needs. Furthermore, there are concerns that Maslow appropriated his theory from the Siksika (Blackfoot) Nation. Dr. Cindy Blackstock (Gitksan First Nation member, as cited in Michel, 2014) explains the Blackfoot belief involves a tipi with three levels: self-actualization at the base; community actualization in the middle; and cultural perpetuity at the top. Maslow visited the Siksika Nation in 1938 and published his theory in 1943. Bray (2019) explains more about Maslow's hierarchy of needs and its alignment with the Siksika Nation. You should be informed of Maslow's hierarchy, but you should also be aware that critiques of this theory exist.

Gardner's Theory of Multiple Intelligences

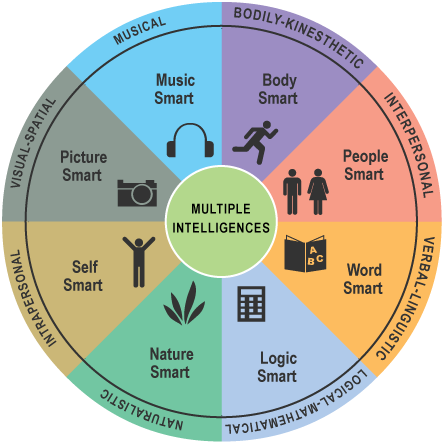

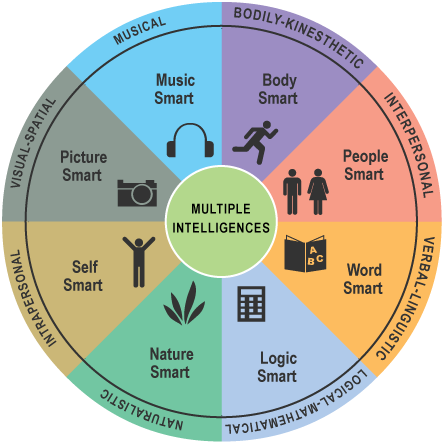

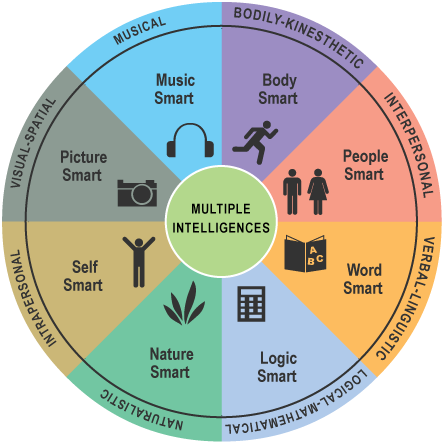

Teachers need to determine students’ areas of strength and need to allow students to work and grow in those areas. One approach to doing this is to determine students’ strengths in different intelligence areas. Theorist Howard Gardner (2004, 2006) initially proposed eight multiple intelligences (see Figure 2.3), but he later added two more areas: existential and moral intelligence.

Gardner's Theory DeBunked!

Based on extensive research, Gardner's theory has been declared a "neuromyth." The original theory was based on a survey of literature, but had no empirical evidence to support this theory. Though there is very little educational research evidence to support instructing students in these eight intelligences (for example: you should not plan a lesson eight different ways to address all eight intelligences in one lesson!), Gardner’s goal was to ensure that teachers did not just focus on verbal and mathematical intelligences in their teaching, which are two very common foci of instruction in schools. Avoid labeling students according to this theory.

Figure 2.3: Gardner's Multiple Intelligences

Similarly, while we often can hear reference to learning styles (often including visual, auditory, reading/writing, and kinesthetic, or VARK), Learning Styles has NO empirical research-based support. Instead, “people’s approaches to learning can, do, and should vary with context. In other words, people learn different things in different ways. Rather than assessing and labeling students as particular kinds of learners and planning accordingly, a wise teacher will do the following:

- Offer students options for learning and expressing learning

- Help them reflect on strategies for mastering and using critical content

- Guide them in knowing when to modify an approach to learning when it proves to be inefficient or ineffective in achieving the student’s goals” (Sousa & Tomlinson, 2018, p. 161-162).

Learn more about the myth of learning styles in the video below.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rhgwIhB58PA

Theoretical Perspectives on Development

While all human beings are unique and grow, learn, and change at different rates and in different ways, there are some common trends of development that impact the trajectories our students follow. Two foundational theories of development are Piaget’s cognitive developmental theory and Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory.

Cognitive Developmental Theory: Piaget

Cognitive developmental theorists such as Jean Piaget posit that we move from birth to adulthood in predictable stages (Huitt & Hummel, 2003). These theorists argue these stages of development do not vary and are distinct from one other. While rates of progress vary by child, the sequence is the same and skipping stages is impossible. Therefore, progression through stages is essentially similar for each child.

In 1936, Piaget proposed four stages of cognitive development for children:

- the sensorimotor stage, which ranges from birth to age two;

- the preoperational stage, ranging from age two through age six or seven;

- the concrete operational stage, ranging from age six or seven through age 11 or 12;

- and the formal operational stage, ranging from age 11 or 12 through adulthood.

Piaget argued that key abilities are acquired at each stage. We will now look at each stage in depth, along with videos demonstrating these abilities in action.

In the sensorimotor stage, little children learn about their surroundings through their senses. In addition, the idea of object permanence is emphasized. This is a child’s realization that things continue to exist even if they are not in view. An example is when parents play peek-a-boo with their infants. The child sees that the parent or caregiver is actually gone when the parent’s or caregiver’s hands are in front of their faces. The video below demonstrates the idea of object permanence.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ue8y-JVhjS0

In the preoperational stage, children develop language, imagination, and memory, working toward symbolic thought. One of the key ideas is the principle of conservation, meaning that specific properties of objects remain the same even if other properties change. The notion of centration is critical here in that children only pay attention to one aspect of a situation. An example is filling a shallow round container with water, then pouring the same amount of water into a skinny container. The child in the preoperational stage will say that there is now more water in the skinny container, even though no additional liquid was added. The video below demonstrates the principle of conservation.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GLj0IZFLKvg&feature=related

Additionally, in the preoperational stage, Piaget suggested that children have egocentric thinking, meaning that they lack the ability to see situations from another person’s point of view. The video below demonstrates the idea of egocentrism.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OinqFgsIbh0&feature=related

In the concrete operational stage, children begin to think more logically and abstractly and can now master the idea of conservation as they work toward operational thought. Children in this stage are less egocentric than before. Key developments in this stage include the notions of reversibility, which is defined as the ability to change direction in linear thinking to return to starting point, and transitivity, which is the ability to infer relationships between two objects based upon objects’ relation to a third object in serial order. The video below demonstrates the ideas of reversibility and transitivity.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UNmUjRf0ekQ

Finally, the formal operational stage continues through adulthood. This is when we can better reason and understand hypothetical situations as we develop abstract thought. Key ideas include metacognition, which is the ability to monitor and think about your own thinking; and the ability to compare abstract relationships, such as to generate laws, principles, or theories. The video below demonstrates the idea of hypothetical thinking, where we see how a boy in the concrete operational stage and a woman in the formal operations stage respond to the same scenario.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zjJdcXA1KH8&feature=related

In addition to his four stages of cognitive development for children, Piaget also discussed how we add new information to our existing understandings. Key terms in his conceptualization of cognitive constructivism include schema, assimilation, accommodation, disequilibrium, and equilibrium. Schema refers to the ways in which we organize information as we confront new ideas. For example, children learn what a wallet is and that it generally contains money. Next they learn that a wallet can be carried in various places, i.e. a pocket or a purse. The child is making a connection now between the idea of a wallet and the category of places where it can be carried. The child’s schema is developing as ideas begin to interconnect and form what we can call a blueprint of concepts and their connections.

In order to develop schema, Piaget would have said that children (and all of us) need to experience disequilibrium. Children are in a state of equilibrium as they go about in the world. As they encounter a new concept to add to their schema, they experience disequilibrium where they need to process how this new information fits into their schema. They do this in two ways: assimilation and accommodation. Assimilation uses existing schema to interpret new situations. Accommodation involves changing schema to accommodate new schema and return to a state of equilibrium. Let’s try an example. A child knows that banging a fork on a table makes noise, and the fork does not break. That child and concept are in a state of equilibrium, with the existing schema of knowing banging things on tables does not break the item. The next day, a parent gives the child a sippy cup. The child bangs it on the table and it also does not break, so the child assimilates this new object into their existing understanding that banging items on tables does not break the item. One day, a parent gives the child an egg. The child proceeds to bang it on the table, but what happens? The egg breaks, sending the child’s schema--everything that they bang on the table remains unbroken--into a state of disequilibrium. That child must accommodate that new information into their schema. Once this new information is accommodated, the child can once again move into equilibrium. The video below explains the idea of schema, assimilation and accommodation.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xj0CUeyucJw

Sociocultural Theory: Vygotsky

Whereas Piaget viewed learning in specific stages where children engage in cognitive constructivism (Huitt & Hummel, 2003), thus emphasizing the role of the individual in learning, Lev Vygotsky viewed learning as socially constructed (Vygotsky, 1986). Vygotsky was a Russian psychologist in the 1920s and 1930s, but his work was not known to the Western world until the 1970s. He emphasized the role that other people have in an individual’s construction of knowledge, known as social constructivism. He realized that we learned more with other people than we learned all by ourselves.

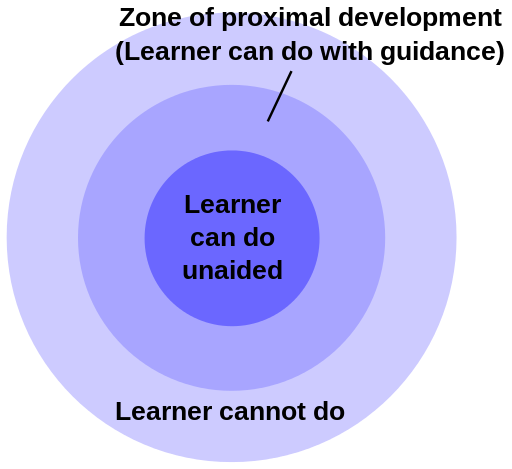

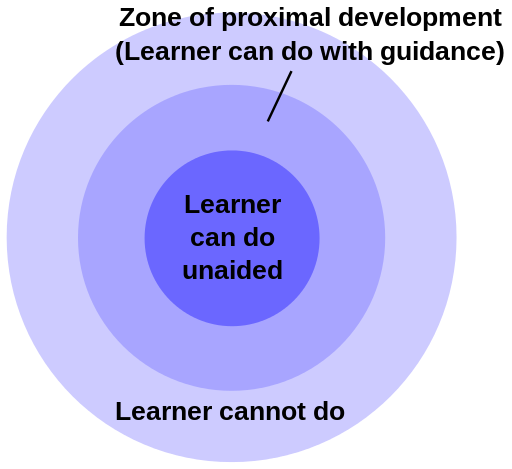

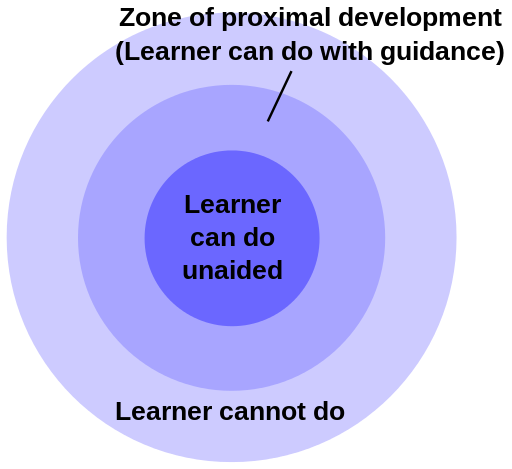

One of the major tenets in Vygotsky’s theory of learning (Vygotsky, 1986) is the zone of proximal development. As shown in Figure 2.4, the zone of proximal development (ZPD) is the difference between what a learner can do without help and what they can do with help.

Figure 2.4: Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD)

Vygotsky's often-quoted definition of zone of proximal development says ZPD is "the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance, or in collaboration with more capable peers" (Vygotsky, 1978, p. 86). The concept of scaffolding is closely related to the ZPD. Scaffolding is a process through which a teacher or more competent peer gives aid to the student in her/his ZPD as necessary, and tapers off this aid as it becomes unnecessary, much as a scaffold is removed from a building during construction. While we often think of a teacher as the more “expert other” in ZPD, this individual does not have to be a teacher. In fact, sometimes our own students are the more “expert other” in certain areas. Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory emphasizes that we can learn more with and through each other.

https://youtu.be/kTIUAZbKidw

CRITICAL LENS: CONTEXT MATTERS

As we examine these four theories, it is also important to analyze the context of this work: these theorists and researchers all identified as White, often working with individuals close to them to conduct research (for example, Piaget studied his own children). We all absorb certain beliefs and social norms from our communities, so knowing that these theories came from communities that represented fairly limited diversity is important.

Conclusion

In this chapter, we surveyed two systems that influence students’ learning (Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences) and two theoretical perspectives on development (Piaget’s cognitive developmental theory and Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory).

There are several modern theories that have strong research supporting them. These theories are part of a course in Educational Psychology.

As we saw in the Unlearning Box at the beginning of this chapter, all of our students bring different characteristics with them to our classrooms. While some (not all!) students may share certain characteristics and overall developmental trajectories, teachers must acknowledge that each student in the classroom has individual strengths and needs. Only once we know our students as individual learners will we be able to teach them effectively.

“He is just so lazy - sits there and refuses to do any work. And his parents are no help - they never return phone calls or emails. Why bother?”

This is an actual statement by a teacher frustrated with a fourth grader in her classroom. What this teacher did not know was the context in which the student was living. He was homeless and living out of his mother’s car. His mother couldn’t pay her cell phone bill, so had no way of receiving phone calls or emails. The teacher failed to realize what else could be contributing to his “laziness”: hunger, fear, lack of adequate care, and a parent unavailable to him with her own struggle to survive.

In order to teach our students, we have to know them. Multiple influences affect our students and their environments.

Chapter Outline

In this chapter, we will investigate how different systems influence learning and we will explore two theoretical perspectives on development.

Systems that Influence Student Learning

As humans grow and develop, there are many different systems that influence this development. Think about systems as interrelated parts of a whole, just like the solar system is made up of planets and other celestial objects. Two theories that consider various impacts on student learning are Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences.

Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs

One way to conceptualize influences on student learning is through need systems. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (see Figure 2.2) theorized that people are motivated by a succession of hierarchical needs (McLeod, 2020). Originally, Maslow discussed five levels of needs shaped in the form of a pyramid. He later adjusted the pyramid to include eight levels of needs, incorporating need for knowledge and understanding, aesthetic needs, and transcendence. Figure 2.2 depicts these eight needs in hierarchical order. The first four levels are deficiency needs, and the upper four are growth needs. The first four are essential to a student’s well being, and they build on each other. These deficiency needs must be satisfied before a person can move on to the growth needs. Moving to the growth needs is essential for learning to truly occur. Now we will examine each of the elements within Maslow’s hierarchy of needs in more depth.

Of the eight levels, the first is physiological needs. These needs include food, water, and shelter. In this case, do students have a home where they are properly nourished? If not, students who are not attending to their work may be hungry, not just daydreaming. This is why free and reduced breakfast and lunch programs are so essential in schools.

Safety and security needs are the second level of the pyramid. Students need to feel that they are not in harm’s way. Schools are responsible for maintaining safe environments for students and classrooms need to feel safe and secure. This requires classroom rules that all students follow, including protecting students from bullying and threatening behavior. There are effective and less effective ways to structure a classroom so that it is safe for all students.

The third level of Maslow’s hierarchy is love and belonging. In schools, these needs are met primarily through positive relationships with teachers and peers, and people with whom students regularly interact. Feelings of acceptance are necessary here, and teachers can play a huge role in creating these feelings for students. It is critical that teachers are non-judgmental towards their students. It does not matter how you, as a teacher, may feel about a student’s lifestyle choices, beliefs, political views or family structures; it matters how a student perceives you as someone who accepts them, no matter what.

The fourth and final level of deficiency needs is esteem needs: self-worth and self-esteem. Students must have experiences in schools and classrooms that lead them to feel positive about themselves. Self-esteem is what students think and feel about themselves, and it contributes to their confidence. Self-worth is students knowing that they are valuable and lovable.

Figure 2.2: Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs

Following the four deficiency needs in Maslow’s hierarchy are growth needs. Once students reach growth needs, they are ready for true, meaningful learning. The fifth element, the need to know and understand, is also referred to as cognitive needs. It is our job as educators to motivate students to want to know and understand the world around them. In order to do this, we must be sure we are providing our students with questions that move them to higher-order thinking skills. An instructional model that is well-developed and utilized in many classrooms is Bloom’s Taxonomy. It can be used to classify learning objectives, and it is a way to encourage students to think more deeply about content and motivate them to want to know more.

The sixth level of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is aesthetic needs. At this level, we can learn to appreciate the beauty of the natural world. When we are focused on deficiency needs in the lower levels of Maslow’s theory, it is more difficult to see the beauty in our environment and surroundings. In education, students need to be exposed to the beauty that is reflected in the arts: music, visual arts and theatre. Most schools separate these into distinct periods or blocks; however, it is essential that arts are also integrated into the curriculum. Additionally, students should be exposed to arts outside of Western art so they encounter art forms that include representations of all cultures, including their own.

Self-actualization is the seventh need on the pyramid and is another growth need. Maslow indicated that this happens as we age. It is our intrinsic need to make the most of our lives and reach our full potential. A way of thinking about this is to consider what we think of our ideal selves--or, for young people, how they see themselves or what they see themselves having achieved and broadly experienced as they get to later stages in life.

Finally, transcendence needs are the highest on Maslow’s hierarchy. Maslow (1971) stated, “transcendence refers to the very highest levels of human consciousness, behaving and relating, as ends rather than means, to oneself, to significant others, to human beings in general, to other species, to nature, and to the cosmos” (p. 269). Though most of us in K-12 schools will not experience students at this level, it is important to note that this is the goal in life, according to Maslow.

Critical Lens: Origins of Theories

Sometimes we hold theories as universal truths without stopping to consider the context in which they were made. For example, Bridgman, Cummings, and Ballard (2019) recently investigated the origin of Maslow's theory and discovered that he himself never created the well-known pyramid model to represent the hierarchy of needs. Furthermore, there are concerns that Maslow appropriated his theory from the Siksika (Blackfoot) Nation. Dr. Cindy Blackstock (Gitksan First Nation member, as cited in Michel, 2014) explains the Blackfoot belief involves a tipi with three levels: self-actualization at the base; community actualization in the middle; and cultural perpetuity at the top. Maslow visited the Siksika Nation in 1938 and published his theory in 1943. Bray (2019) explains more about Maslow's hierarchy of needs and its alignment with the Siksika Nation. You should be informed of Maslow's hierarchy, but you should also be aware that critiques of this theory exist.

Gardner's Theory of Multiple Intelligences

Teachers need to determine students’ areas of strength and need to allow students to work and grow in those areas. One approach to doing this is to determine students’ strengths in different intelligence areas. Theorist Howard Gardner (2004, 2006) initially proposed eight multiple intelligences (see Figure 2.3), but he later added two more areas: existential and moral intelligence.

Gardner's Theory DeBunked!

Based on extensive research, Gardner's theory has been declared a "neuromyth." The original theory was based on a survey of literature, but had no empirical evidence to support this theory. Though there is very little educational research evidence to support instructing students in these eight intelligences (for example: you should not plan a lesson eight different ways to address all eight intelligences in one lesson!), Gardner’s goal was to ensure that teachers did not just focus on verbal and mathematical intelligences in their teaching, which are two very common foci of instruction in schools. Avoid labeling students according to this theory.

Figure 2.3: Gardner's Multiple Intelligences

Similarly, while we often can hear reference to learning styles (often including visual, auditory, reading/writing, and kinesthetic, or VARK), Learning Styles has NO empirical research-based support. Instead, “people’s approaches to learning can, do, and should vary with context. In other words, people learn different things in different ways. Rather than assessing and labeling students as particular kinds of learners and planning accordingly, a wise teacher will do the following:

- Offer students options for learning and expressing learning

- Help them reflect on strategies for mastering and using critical content

- Guide them in knowing when to modify an approach to learning when it proves to be inefficient or ineffective in achieving the student’s goals” (Sousa & Tomlinson, 2018, p. 161-162).

Learn more about the myth of learning styles in the video below.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rhgwIhB58PA

Theoretical Perspectives on Development

While all human beings are unique and grow, learn, and change at different rates and in different ways, there are some common trends of development that impact the trajectories our students follow. Two foundational theories of development are Piaget’s cognitive developmental theory and Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory.

Cognitive Developmental Theory: Piaget

Cognitive developmental theorists such as Jean Piaget posit that we move from birth to adulthood in predictable stages (Huitt & Hummel, 2003). These theorists argue these stages of development do not vary and are distinct from one other. While rates of progress vary by child, the sequence is the same and skipping stages is impossible. Therefore, progression through stages is essentially similar for each child.

In 1936, Piaget proposed four stages of cognitive development for children:

- the sensorimotor stage, which ranges from birth to age two;

- the preoperational stage, ranging from age two through age six or seven;

- the concrete operational stage, ranging from age six or seven through age 11 or 12;

- and the formal operational stage, ranging from age 11 or 12 through adulthood.

Piaget argued that key abilities are acquired at each stage. We will now look at each stage in depth, along with videos demonstrating these abilities in action.

In the sensorimotor stage, little children learn about their surroundings through their senses. In addition, the idea of object permanence is emphasized. This is a child’s realization that things continue to exist even if they are not in view. An example is when parents play peek-a-boo with their infants. The child sees that the parent or caregiver is actually gone when the parent’s or caregiver’s hands are in front of their faces. The video below demonstrates the idea of object permanence.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ue8y-JVhjS0

In the preoperational stage, children develop language, imagination, and memory, working toward symbolic thought. One of the key ideas is the principle of conservation, meaning that specific properties of objects remain the same even if other properties change. The notion of centration is critical here in that children only pay attention to one aspect of a situation. An example is filling a shallow round container with water, then pouring the same amount of water into a skinny container. The child in the preoperational stage will say that there is now more water in the skinny container, even though no additional liquid was added. The video below demonstrates the principle of conservation.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GLj0IZFLKvg&feature=related

Additionally, in the preoperational stage, Piaget suggested that children have egocentric thinking, meaning that they lack the ability to see situations from another person’s point of view. The video below demonstrates the idea of egocentrism.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OinqFgsIbh0&feature=related

In the concrete operational stage, children begin to think more logically and abstractly and can now master the idea of conservation as they work toward operational thought. Children in this stage are less egocentric than before. Key developments in this stage include the notions of reversibility, which is defined as the ability to change direction in linear thinking to return to starting point, and transitivity, which is the ability to infer relationships between two objects based upon objects’ relation to a third object in serial order. The video below demonstrates the ideas of reversibility and transitivity.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UNmUjRf0ekQ

Finally, the formal operational stage continues through adulthood. This is when we can better reason and understand hypothetical situations as we develop abstract thought. Key ideas include metacognition, which is the ability to monitor and think about your own thinking; and the ability to compare abstract relationships, such as to generate laws, principles, or theories. The video below demonstrates the idea of hypothetical thinking, where we see how a boy in the concrete operational stage and a woman in the formal operations stage respond to the same scenario.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zjJdcXA1KH8&feature=related

In addition to his four stages of cognitive development for children, Piaget also discussed how we add new information to our existing understandings. Key terms in his conceptualization of cognitive constructivism include schema, assimilation, accommodation, disequilibrium, and equilibrium. Schema refers to the ways in which we organize information as we confront new ideas. For example, children learn what a wallet is and that it generally contains money. Next they learn that a wallet can be carried in various places, i.e. a pocket or a purse. The child is making a connection now between the idea of a wallet and the category of places where it can be carried. The child’s schema is developing as ideas begin to interconnect and form what we can call a blueprint of concepts and their connections.

In order to develop schema, Piaget would have said that children (and all of us) need to experience disequilibrium. Children are in a state of equilibrium as they go about in the world. As they encounter a new concept to add to their schema, they experience disequilibrium where they need to process how this new information fits into their schema. They do this in two ways: assimilation and accommodation. Assimilation uses existing schema to interpret new situations. Accommodation involves changing schema to accommodate new schema and return to a state of equilibrium. Let’s try an example. A child knows that banging a fork on a table makes noise, and the fork does not break. That child and concept are in a state of equilibrium, with the existing schema of knowing banging things on tables does not break the item. The next day, a parent gives the child a sippy cup. The child bangs it on the table and it also does not break, so the child assimilates this new object into their existing understanding that banging items on tables does not break the item. One day, a parent gives the child an egg. The child proceeds to bang it on the table, but what happens? The egg breaks, sending the child’s schema--everything that they bang on the table remains unbroken--into a state of disequilibrium. That child must accommodate that new information into their schema. Once this new information is accommodated, the child can once again move into equilibrium. The video below explains the idea of schema, assimilation and accommodation.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xj0CUeyucJw

Sociocultural Theory: Vygotsky

Whereas Piaget viewed learning in specific stages where children engage in cognitive constructivism (Huitt & Hummel, 2003), thus emphasizing the role of the individual in learning, Lev Vygotsky viewed learning as socially constructed (Vygotsky, 1986). Vygotsky was a Russian psychologist in the 1920s and 1930s, but his work was not known to the Western world until the 1970s. He emphasized the role that other people have in an individual’s construction of knowledge, known as social constructivism. He realized that we learned more with other people than we learned all by ourselves.

One of the major tenets in Vygotsky’s theory of learning (Vygotsky, 1986) is the zone of proximal development. As shown in Figure 2.4, the zone of proximal development (ZPD) is the difference between what a learner can do without help and what they can do with help.

Figure 2.4: Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD)

Vygotsky's often-quoted definition of zone of proximal development says ZPD is "the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance, or in collaboration with more capable peers" (Vygotsky, 1978, p. 86). The concept of scaffolding is closely related to the ZPD. Scaffolding is a process through which a teacher or more competent peer gives aid to the student in her/his ZPD as necessary, and tapers off this aid as it becomes unnecessary, much as a scaffold is removed from a building during construction. While we often think of a teacher as the more “expert other” in ZPD, this individual does not have to be a teacher. In fact, sometimes our own students are the more “expert other” in certain areas. Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory emphasizes that we can learn more with and through each other.

https://youtu.be/kTIUAZbKidw

CRITICAL LENS: CONTEXT MATTERS

As we examine these four theories, it is also important to analyze the context of this work: these theorists and researchers all identified as White, often working with individuals close to them to conduct research (for example, Piaget studied his own children). We all absorb certain beliefs and social norms from our communities, so knowing that these theories came from communities that represented fairly limited diversity is important.

Conclusion

In this chapter, we surveyed two systems that influence students’ learning (Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences) and two theoretical perspectives on development (Piaget’s cognitive developmental theory and Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory).

There are several modern theories that have strong research supporting them. These theories are part of a course in Educational Psychology.

As we saw in the Unlearning Box at the beginning of this chapter, all of our students bring different characteristics with them to our classrooms. While some (not all!) students may share certain characteristics and overall developmental trajectories, teachers must acknowledge that each student in the classroom has individual strengths and needs. Only once we know our students as individual learners will we be able to teach them effectively.

A substitute teacher was supposed to give an assessment while the classroom teacher was away, but one student refused to take the test. “He started yelling and walked out of the room, saying he wasn’t going to take this test that the teacher left for him. He kept saying that he is supposed to have questions read aloud to him, but that isn’t fair and I wasn’t going to do it!” Sometimes we think that fairness means everyone is treated the same way, but in reality, “fairness” involves meeting the needs of different students. In this example, the student had an IEP(individualized Education Plan) accommodation that allowed him to have tests read aloud to him. When considering instruction, and assessment, sometimes treating all students the same is actually quite unfair, since students have different learning needs and strengths.

In this chapter, we will begin to explore the standards and planning for instruction.

Chapter Outline

Effective teachers must plan effective lessons, which are based on standards. Standards vary depending on the state where you teach. Standards tell teachers the key information that students should understand in specific content areas at varying grade levels. As a teacher, you are responsible for knowing the standards you are responsible for teaching and planning effective lessons to help students learn the information explained in the standards. An elementary school teacher is responsible for standards in English, math, science, and social studies; a secondary teacher typically specializes in one area, such as history. There are also standards for fine arts, languages, and other areas.

Some states use state-developed standards, while other states adopted the Common Core State Standards[5]. These standards have been an attempt to move the nation closer to a unified set of standards. As of 2021, 41 states, the District of Columbia, four territories, and the Department of Defense Education Activity (DoDEA) have adopted them, with varying degrees of implementation and support at the district levels (Common Core States Standards Initiative, 2021).

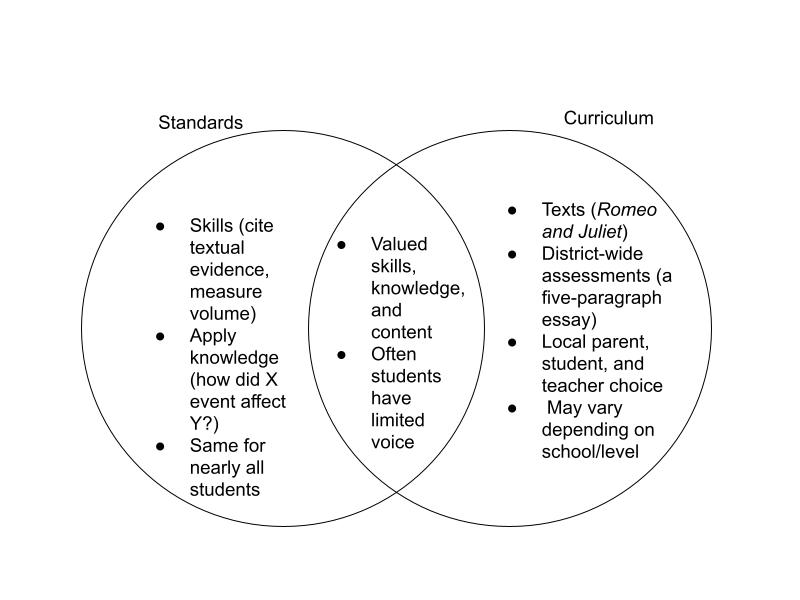

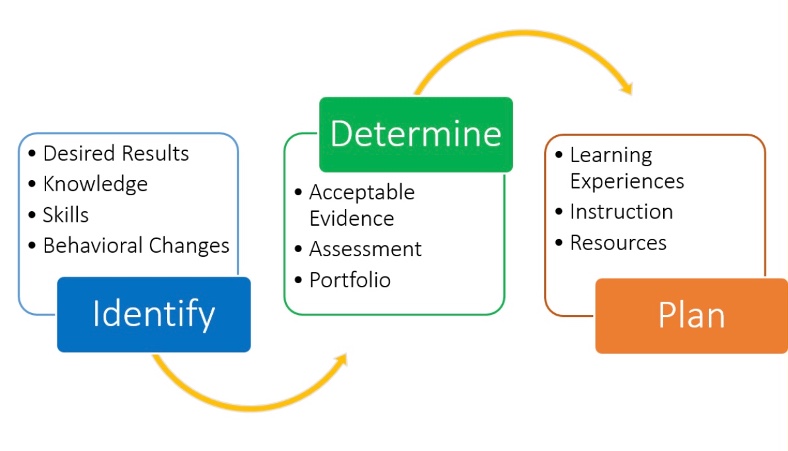

It is not uncommon to hear a teacher or parent say that they want schools to “cover” curriculum or standards; however, “coverage” is not conducive to deep understanding. Instead, a teacher should review the standards and local curriculum as a part of their planning, with a focus on big, transferable ideas (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005). This is considered depth of material, rather than simply breadth of material.