19

Sexuality is one of the fundamental drives behind everyone’s feelings, thoughts, and behaviors. It defines the means of biological reproduction, describes psychological and sociological representations of self, and orients a person’s attraction to others. Further, it shapes the brain and body to be pleasure-seeking. Yet, as important as sexuality is to being human, it is often viewed as a taboo topic for personal or scientific inquiry.

Learning Objectives

- Explain how scientists study human sexuality.

- Share a definition of human sexuality.

- Distinguish between sex, gender, and sexual orientation.

- Review common and alternative sexual behaviors.

- Appraise how pleasure, sexual behaviors, and consent are intertwined.

Introduction

Sex makes the world go around: It makes babies bond, children giggle, adolescents flirt, and adults have babies. It is addressed in the holy books of the world’s great religions, and it infiltrates every part of society. It influences the way we dress, joke, and talk. In many ways, sex defines who we are. It is so important, the eminent neuropsychologist Karl Pribram (1958) described sex as one of four basic human drive states. Drive states motivate us to accomplish goals. They are linked to our survival. According to Pribram, feeding, fighting, fleeing, and sex are the four drives behind every thought, feeling, and behavior. Since these drives are so closely associated with our psychological and physical health, you might assume people would study, understand, and discuss them openly. Your assumption would be generally correct for three of the four drives (Malacane & Beckmeyer, 2016). Can you guess which drive is the least understood and openly discussed?

This module presents an opportunity for you to think openly and objectively about sex. Without shame or taboo, using science as a lens, we examine fundamental aspects of human sexuality—including gender, sexual orientation, fantasies, behaviors, paraphilias, and sexual consent.

The History of Scientific Investigations of Sex

The history of human sexuality is as long as human history itself—200,000+ years and counting (Antón & Swisher, 2004). For almost as long as we have been having sex, we have been creating art, writing, and talking about it. Some of the earliest recovered artifacts from ancient cultures are thought to be fertility totems. The Hindu Kama Sutra (400 BCE to 200 CE)—an ancient text discussing love, desire, and pleasure—includes a how-to manual for having sexual intercourse. Rules, advice, and stories about sex are also contained in the Muslim Qur’an, Jewish Torah, and Christian Bible.

By contrast, people have been scientifically investigating sex for only about 125 years. The first scientific investigations of sex employed the case study method of research. Using this method, the English physician Henry Havelock Ellis (1859-1939) examined diverse topics within sexuality, including arousal and masturbation. From 1897 to 1923, his findings were published in a seven-volume set of books titled Studies in the Psychology of Sex. Among his most noteworthy findings is that transgender people are distinct from homosexual people. Ellis’s studies led him to be an advocate of equal rights for women and comprehensive human sexuality education in public schools.

Using case studies, the Austrian neurologist Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) is credited with being the first scientist to link sex to healthy development and to recognize humans as being sexual throughout their lifespans, including childhood (Freud, 1905). Freud (1923) argued that people progress through five stages of psychosexual development: oral, anal, phallic, latent, and genital. According to Freud, each of these stages could be passed through in a healthy or unhealthy manner. In unhealthy manners, people might develop psychological problems, such as frigidity, impotence, or anal-retentiveness.

The American biologist Alfred Kinsey (1894-1956) is commonly referred to as the father of human sexuality research. Kinsey was a world-renowned expert on wasps but later changed his focus to the study of humans. This shift happened because he wanted to teach a course on marriage but found data on human sexual behavior lacking. He believed that sexual knowledge was the product of guesswork and had never really been studied systematically or in an unbiased way. He decided to collect information himself using the survey method, and set a goal of interviewing 100 thousand people about their sexual histories. Although he fell short of his goal, he still managed to collect 18 thousand interviews! Many “behind closed doors” behaviors investigated by contemporary scientists are based on Kinsey’s seminal work.

Today, a broad range of scientific research on sexuality continues. It’s a topic that spans various disciplines, including anthropology, biology, neurology, psychology, and sociology.

Sex, Gender, and Sexual Orientation: Three Different Parts of You

Applying for a credit card or filling out a job application requires your name, address, and birth-date. Additionally, applications usually ask for your sex or gender. It’s common for us to use the terms “sex” and “gender” interchangeably. However, in modern usage, these terms are distinct from one another.

Sex describes means of biological reproduction. Sex includes sexual organs, such as ovaries—defining what it is to be a female—or testes—defining what it is to be a male. Interestingly, biological sex is not as easily defined or determined as you might expect (see the section on variations in sex, below). By contrast, the term gender describes psychological (gender identity) and sociological (gender role) representations of biological sex. At an early age, we begin learning cultural norms for what is considered masculine and feminine. For example, children may associate long hair or dresses with femininity. Later in life, as adults, we often conform to these norms by behaving in gender-specific ways: as men, we build houses; as women, we bake cookies (Marshall, 1989; Money et al., 1955; Weinraub et al., 1984).

Because cultures change over time, so too do ideas about gender. For example, European and American cultures today associate pink with femininity and blue with masculinity. However, less than a century ago, these same cultures were swaddling baby boys in pink, because of its masculine associations with “blood and war,” and dressing little girls in blue, because of its feminine associations with the Virgin Mary (Kimmel, 1996).

Sex and gender are important aspects of a person’s identity. However, they do not tell us about a person’s sexual orientation (Rule & Ambady, 2008). Sexual orientation refers to a person’s sexual attraction to others. Within the context of sexual orientation, sexual attraction refers to a person’s capacity to arouse the sexual interest of another, or, conversely, the sexual interest one person feels toward another.

While some argue that sexual attraction is primarily driven by reproduction (e.g., Geary, 1998), empirical studies point to pleasure as the primary force behind our sex drive. For example, in a survey of college students who were asked, “Why do people have sex?” respondents gave more than 230 unique responses, most of which were related to pleasure rather than reproduction (Meston & Buss, 2007). Here’s a thought-experiment to further demonstrate how reproduction has relatively little to do with driving sexual attraction: Add the number of times you’ve had and hope to have sex during your lifetime. With this number in mind, consider how many times the goal was (or will be) for reproduction versus how many it was (or will be) for pleasure. Which number is greater?

Although a person’s intimate behavior may have sexual fluidity —changing due to circumstances (Diamond, 2009)—sexual orientations are relatively stable over one’s lifespan, and are genetically rooted (Frankowski, 2004). One method of measuring these genetic roots is the sexual orientation concordance rate (SOCR). An SOCR is the probability that a pair of individuals has the same sexual orientation. SOCRs are calculated and compared between people who share the same genetics (monozygotic twins, 99%); some of the same genetics (dizygotic twins, 50%); siblings (50%); and non-related people, randomly selected from the population. Researchers find SOCRs are highest for monozygotic twins; and SOCRs for dizygotic twins, siblings, and randomly-selected pairs do not significantly differ from one another (Bailey et al. 2016; Kendler et al., 2000). Because sexual orientation is a hotly debated issue, an appreciation of the genetic aspects of attraction can be an important piece of this dialogue.

On Being Normal: Variations in Sex, Gender, and Sexual Orientation

“Only the human mind invents categories and tries to force facts into separated pigeon-holes. The living world is a continuum in each and every one of its aspects. The sooner we learn this concerning human sexual behavior, the sooner we shall reach a sound understanding of the realities of sex.” (Kinsey, Pomeroy, & Martin, 1948, pp. 638–639)

We live in an era when sex, gender, and sexual orientation are controversial religious and political issues. Some nations have laws against homosexuality, while others have laws protecting same-sex marriages. At a time when there seems to be little agreement among religious and political groups, it makes sense to wonder, “What is normal?” and, “Who decides?”

The international scientific and medical communities (e.g., World Health Organization, World Medical Association, World Psychiatric Association, Association for Psychological Science) view variations of sex, gender, and sexual orientation as normal. Furthermore, variations of sex, gender, and sexual orientation occur naturally throughout the animal kingdom. More than 500 animal species have homosexual or bisexual orientations (Lehrer, 2006). More than 65,000 animal species are intersex—born with either an absence or some combination of male and female reproductive organs, sex hormones, or sex chromosomes (Jarne & Auld, 2006). In humans, intersex individuals make up about two percent—more than 150 million people—of the world’s population (Blackless et al., 2000). There are dozens of intersex conditions, such as Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome and Turner’s Syndrome (Lee et al., 2006). The term “syndrome” can be misleading; although intersex individuals may have physical limitations (e.g., about a third of Turner’s individuals have heart defects; Matura et al., 2007), they otherwise lead relatively normal intellectual, personal, and social lives. In any case, intersex individuals demonstrate the diverse variations of biological sex.

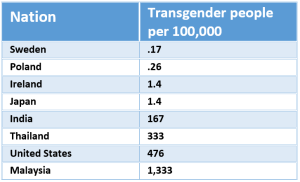

Just as biological sex varies more widely than is commonly thought, so too does gender. Cisgender individuals’ gender identities correspond with their birth sexes, whereas transgender individuals’ gender identities do not correspond with their birth sexes. Because gender is so deeply ingrained culturally, rates of transgender individuals vary widely around the world (see Table 19.1).

Although incidence rates of transgender individuals differ significantly between cultures, transgender females (TGFs)—whose birth sex was male—are by far the most frequent type of transgender individuals worldwide. Of the 18 countries studied by Meier and Labuski (2013), 16 of them had higher rates of TGFs than transgender males (TGMs)—whose birth sex was female— and the 18 country TGF to TGM ratio was 3 to 1. TGFs have diverse levels of androgyny—having both feminine and masculine characteristics. For example, five percent of the Samoan population are TGFs referred to as fa’afafine, who range in androgyny from mostly masculine to mostly feminine (Tan, 2016); in Pakistan, India, Nepal, and Bangladesh, TGFs are referred to as hijras, recognized by their governments as a third gender, and range in androgyny from only having a few masculine characteristics to being entirely feminine (Pasquesoone, 2014); and as many as six percent of biological males living in Oaxaca, Mexico are TGFs referred to as muxes, who range in androgyny from mostly masculine to mostly feminine (Stephen, 2002).

Sexual orientation is as diverse as gender identity. Instead of thinking of sexual orientation as being two categories—homosexual and heterosexual—Kinsey argued that it’s a continuum (Kinsey, Pomeroy, & Martin, 1948). He measured orientation on a continuum, using a 7-point Likert scale called the Heterosexual-Homosexual Rating Scale, in which 0 is exclusively heterosexual, 3 is bisexual, and 6 is exclusively homosexual. Later researchers using this method have found 18% to 39% of Europeans and Americans identifying as somewhere between heterosexual and homosexual (Lucas et al., 2017; YouGov.com, 2015). These percentages drop dramatically (0.5% to 1.9%) when researchers force individuals to respond using only two categories (Copen, Chandra, & Febo-Vazquez, 2016; Gates, 2011).

What Are You Doing? A Brief Guide to Sexual Behavior

Just as we may wonder what characterizes particular gender or sexual orientations as “normal,” we might have similar questions about sexual behaviors. What is considered sexually normal depends on culture. Some cultures are sexually-restrictive—such as one extreme example off the coast of Ireland, studied in the mid-20th century, known as the island of Inis Beag. The inhabitants of Inis Beag detested nudity and viewed sex as a necessary evil for the sole purpose of reproduction. They wore clothes when they bathed and even while having sex. Further, sex education was nonexistent, as was breast feeding (Messenger, 1989). By contrast, Mangaians, of the South Pacific island of A’ua’u, are an example of a highly sexually-permissive culture. Young Mangaian boys are encouraged to masturbate. By age 13, they’re instructed by older males on how to sexually perform and maximize orgasms for themselves and their partners. When the boys are a bit older, this formal instruction is replaced with hands-on coaching by older females. Young girls are also expected to explore their sexuality and develop a breadth of sexual knowledge before marriage (Marshall & Suggs, 1971). These cultures make clear that what are considered sexually normal behaviors depends on time and place.

Sexual behaviors are linked to, but distinct from, fantasies. Leitenberg and Henning (1995) define sexual fantasies as “any mental imagery that is sexually arousing.” One of the more common fantasies is the replacement fantasy—fantasizing about someone other than one’s current partner (Hicks & Leitenberg, 2001). In addition, more than 50% of people have forced-sex fantasies (Critelli & Bivona, 2008). However, this does not mean most of us want to be cheating on our partners or be involved in sexual assault. Sexual fantasies are not equal to sexual behaviors.

Sexual fantasies are often a context for the sexual behavior of masturbation—tactile (physical) stimulation of the body for sexual pleasure. Historically, masturbation has earned a bad reputation; it’s been described as “self-abuse,” and falsely associated with causing adverse side effects, such as hairy palms, acne, blindness, insanity, and even death (Kellogg, 1888). However, empirical evidence links masturbation to increased levels of sexual and marital satisfaction, and physical and psychological health (Hurlburt & Whitaker, 1991; Levin, 2007). There is even evidence that masturbation significantly decreases the risk of developing prostate cancer among males over the age of 50 (Dimitropoulou et al., 2009). Masturbation is common among males and females in the U.S. Robbins et al. (2011) found that 74% of males and 48% of females reported masturbating. However, frequency of masturbation is affected by culture. An Australian study found that only 58% of males and 42% of females reported masturbating (Smith, Rosenthal, & Reichler, 1996). Further, rates of reported masturbation by males and females in India are even lower, at 46% and 13%, respectively (Ramadugu et al., 2011).

Coital sex is the term for vaginal-penile intercourse, which occurs for about 3 to 13 minutes on average—though its duration and frequency decrease with age (Corty & Guardiani, 2008; Smith et al., 2012). Traditionally, people are known as “virgins” before they engage in coital sex, and have “lost” their virginity afterwards. Durex (2005) found the average age of first coital experiences across 41 different countries to be 17 years, with a low of 16 (Iceland), and a high of 20 (India). There is tremendous variation regarding frequency of coital sex. For example, the average number of times per year a person in Greece (138) or France (120) engages in coital sex is between 1.6 and 3 times greater than in India (75) or Japan (45; Durex, 2005).

Oral sex includes cunnilingus—oral stimulation of the female’s external sex organs, and fellatio—oral stimulation of the male’s external sex organs. The prevalence of oral sex widely differs between cultures—with Western cultures, such as the U.S., Canada, and Austria, reporting higher rates (greater than 75%); and Eastern and African cultures, such as Japan and Nigeria, reporting lower rates (less than 10%; Copen, Chandra, & Febo-Vazquez, 2016; Malacad & Hess, 2010; Wylie, 2009). Not only are there differences between cultures regarding how many people engage in oral sex, there are differences in its very definition. For example, most college students in the U.S. do not believe cunnilingus or fellatio are sexual behaviors—and more than a third of college students believe oral sex is a form of abstinence (Barnett et al., 2017; Horan, Phillips, & Hagan, 1998; Sanders & Reinisch, 1999).

Anal sex refers to penetration of the anus by an object. Anal sex is not exclusively a “homosexual behavior.” The anus has extensive sensory-nerve innervation and is often experienced as an erogenous zone, no matter where a person is on the Heterosexual-Homosexual Rating Scale (Cordeau et al., 2014). When heterosexual people are asked about their sexual behaviors, more than a third (about 40%) of both males and females report having had anal sex at some time during their life (Chandra, Mosher, & Copen, 2011; Copen, Chandra, & Febo-Vazquez, 2016). Comparatively, when homosexual men are asked about their most recent sexual behaviors, more than a third (37%) report having had anal sex (Rosenberger et al., 2011). Like heterosexual people, homosexual people engage in a variety of sexual behaviors, the most frequent being masturbation, romantic kissing, and oral sex (Rosenberger et al., 2011). The prevalence of anal sex widely differs between cultures. For example, people in Greece and Italy report high rates of anal sex (greater than 50%), whereas people in China and India report low rates of anal sex (less than 15%; Durex, 2005).

In contrast to “more common” sexual behaviors, there is a vast array of alternative sexual behaviors. Some of these behaviors, such as voyeurism, exhibitionism, and pedophilia are classified in the DSM as paraphilic disorders—behaviors that victimize and cause harm to others or one’s self (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Sadism—inflicting pain upon another person to experience pleasure for one’s self—and masochism—receiving pain from another person to experience pleasure for one’s self—are also classified in the DSM as paraphilic disorders. However, if an individual consensually engages in these behaviors, the term “disorder” is replaced with the term “interest.” Janus and Janus (1993) found that 14% of males and 11% of females have engaged in some form of sadism and/or masochism.

Sexual Consent

Clearly, people engage in a multitude of behaviors whose variety is limited only by our own imaginations. Further, our standards for what’s normal differs substantially from culture to culture. However, there is one aspect of sexual behavior that is universally acceptable—indeed, fundamental and necessary. At the heart of what qualifies as sexually “normal” is the concept of consent. Sexual consent refers to the voluntary, conscious, and empathic participation in a sexual act, which can be withdrawn at any time (Jozkowski & Peterson, 2013). Sexual consent is the baseline for what are considered normal—acceptable and healthy—behaviors; whereas, nonconsensual sex—i.e., forced, pressured or unconscious participation—is unacceptable and unhealthy. When engaging in sexual behaviors with a partner, a clear and explicit understanding of your boundaries, as well as your partner’s boundaries, is essential. We recommend safer-sex practices, such as condoms, honesty, and communication, whenever you engage in a sexual act. Discussing likes, dislikes, and limits prior to sexual exploration reduces the likelihood of miscommunication and misjudging nonverbal cues. In the heat of the moment, things are not always what they seem. For example, Kristen Jozkowski and her colleagues (2014) found that females tend to use verbal strategies of consent, whereas males tend to rely on nonverbal indications of consent. Awareness of this basic mismatch between heterosexual couples’ exchanges of consent may proactively reduce miscommunication and unwanted sexual advances.

The universal principles of pleasure, sexual behaviors, and consent are intertwined. Consent is the foundation on which sexual activity needs to be built. Understanding and practicing empathic consent requires sexual literacy and an ability to effectively communicate desires and limits, as well as to respect others’ parameters.

Conclusion

Considering the amount of attention people give to the topic of sex, it’s surprising how little most actually know about it. Historically, people’s beliefs about sexuality have emerged as having absolute moral, physical, and psychological boundaries. The truth is, sex is less concrete than most people assume. Gender and sexual orientation, for example, are not either/or categories. Instead, they are continuums. Similarly, sexual fantasies and behaviors vary greatly by individual and culture. Ultimately, open discussions about sexual identity and sexual practices will help people better understand themselves, others, and the world around them.

Text Attribution

Media Attributions

- [Ancient Greek tile]

- 1952-icing-cake

- Intersex Bombus bimaculatus, gyn, female, washington, oh_2014-05-07-18.47.39 ZS PMax

- Couple of two male mallard ducks

- Table 19.1

- Hijra Dancer in Pilgrim’s Market – Lumbini Development Zone – Lumbini – Nepal – 03

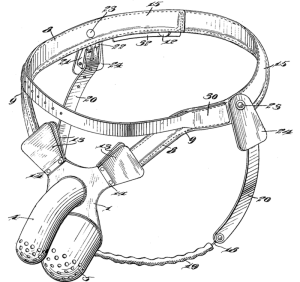

- [Chastity belt]

An in-depth and objective examination of the details of a single person or entity.

Oral, anal, phallic, latency, and genital.

One method of research that uses a predetermined and methodical list of questions, systematically given to samples of individuals, to predict behaviors within the population.

The cultural, social, and psychological meanings that are associated with masculinity and femininity.

A person’s psychological sense of being male or female.

The behaviors, attitudes, and personality traits that are designated as either masculine or feminine in a given culture.

Refers to the direction of emotional and erotic attraction toward members of the opposite sex, the same sex, or both sexes.

The capacity a person has to elicit or feel sexual interest.

Personal sexual attributes changing due to psychosocial circumstances.

Twins conceived from a single ovum and a single sperm, therefore genetically identical.

Twins conceived from two ova and two sperm.

Born with either an absence or some combination of male and female reproductive organs, sex hormones, or sex chromosomes.

A term used to describe individuals whose gender matches their biological sex.

A term used to describe individuals whose gender does not match their biological sex.

A transgender person whose birth sex was male.

A transgender person whose birth sex was female.

Having both feminine and masculine characteristics.

Opposite-sex attraction.

Attraction to two sexes.

Same-sex attraction.

Fantasizing about someone other than one’s current partner.

Tactile stimulation of the body for sexual pleasure.

Vaginal-penile intercourse.

Cunnilingus or fellatio.

Oral stimulation of the female’s external sex organs.

Oral stimulation of the male’s external sex organs.

Penetration of the anus by an animate or inanimate object.

Sexual behaviors that cause harm to others or one’s self.

Inflicting pain upon another person to experience pleasure for one’s self.

Receiving pain from another person to experience pleasure for one’s self.

Permission that is voluntary, conscious, and able to be withdrawn at any time.

Doing anything that may decrease the probability of sexual assault, sexually transmitted infections, or unwanted pregnancy; this may include using condoms, honesty, and communication.

The lifelong pursuit of accurate human sexuality knowledge, and recognition of its various multicultural, historical, and societal contexts; the ability to critically evaluate sources and discern empirical evidence from unreliable and inaccurate information; the acknowledgment of humans as sexual beings; and an appreciation of sexuality’s contribution to enhancing one’s well-being and pleasure in life.