Chapter 5: The Pedagogical Framework

The first challenge for education is to think how to even describe the more abstract contours of the present in a way that is neither old wine in new bottles nor new wine in old bottles.

(Jandrić, 2017, p. 115)

Especially after the pandemic and the rapid pace of Artificial Intelligence (AI), the meaning of what a good university is has been reconsidered. Educational theorists such as Goodyear (2022) and Cottam (2019) emphasise relationships and practical action as the driving force of social change and the so-called “good university”. Cottam’s (2019) findings and insightful experience focus on four skills:

- Learning: the skill to drive a life-long adventure of inquiry, creativity, and imagination.

- Health: mental, psychological, and physical well-being as prerequisites for leading a satisfactory livelihood.

- Community: participate in local and international communities and networks.

- Relationships: feeling connected and sharing the responsibility of learning and bonding with others.

In this way of seeing things, Connell’s book The Good University (2019) considers universities as organisations and businesses that could be democratic, engaged, truthful, creative, and sustainable. Hence, the pedagogy must mirror these indicators.

As science, philosophy, and art, pedagogy must embrace a transdisciplinary disposition and research mindset to quickly adapt to the post-digital world’s unpredictability and be future-proof. The term comes from the Greek terms paid and agogos, meaning leader of a child (Holmes & Abington-Cooper, 2001). The term originated in Greece (paidagogia, paidagogos, and pedia), travelled in France in the late 16th century, and was translated into pedagogue and pedagogy in English.

The Science, philosophy, and art of pedagogy in technology-enhanced learning environments is the science and epistemic fluency that could frame the learning theories in praxis (organise learning objectives, evaluate outcomes, design learning analytics, define agency, and orchestrate assessment or impact studies) and media spaces. Pedagogy is the philosophy of how people need to learn, construct new knowledge, work, and collaborate with others for individual and collective prosperity. The philosophical stance embraces ethics, values, empathy, and character education. It is how educators and students re-imagine the world, challenge the status quo, or perceive a threat to their agency. The “interrelationships between policy, theory, knowledge, and rationale are all framed by political and social agendas, cultures of practice and power relations” (Waring & Evans, 2015, p. 27). The artistic element is equally important. The art of teaching repertoire, as the element of surprise, is the secret ingredient of pedagogy. The essence of surprise could be a Eureka moment, a new tool, sharing stories, avatar perspective-taking, or body-swapping in virtual reality. To put it in Stanslavski’s (1949) words, “disturbing the familiar and making the familiar strange.” to enhance learning and nurture empathy (Grove O’Grady, 2020, p. 47).

Developing pedagogy as a theoretical framework is rare because many educators, instructional designers, and researchers have difficulty grasping philosophical approaches that reflect a broader vision and prefer the comfort zone of day-to-day tasks. Pedagogy is a fearful term (Ellis & Goodyear, 2019). In our understanding, it is recommended that educators reflect on their pedagogy as philosophy, science, and the artistic repertoire of lifelong learning. The ultimate learning outcome of the pedagogy is students’ self-efficacy and self-direction.

As discussed in Chapter 2, science has shown that ‘learning friends’ make a difference. Chapter 3 discussed the power of AR as a form of visual literacy. In an early definition:

Visual Literacy refers to a group of vision competencies a human being can develop by seeing and, simultaneously, having and integrating other sensory experiences. The development of these competencies is fundamental to normal human learning. When developed, they enable a visually literate person to discriminate and interpret the visible actions, objects, and symbols, natural or man-made, that he encounters in his environment. Through the creative use of these competencies, he is able to communicate with others. Through the appreciative use of these competencies, he is able to comprehend and enjoy the masterworks of visual communication (John Debes, 1969).

Students and educators, especially in the remote emergency setting, have chosen the inclusive visual language of the internet using all forms of visuals: emoji, videos, 3D animation, QR codes, and augmented reality whenever possible. Visual reading and thinking are inclusive because they assist students facing learning challenges (Sime & Themelis, 2020) and convey meaning by providing a concise and memorable micro-learning experience. That is why students prefer watching a video rather than reading a text. Their preferences need to be thought of. The United Nations’ sustainable goals focus on improving education to respect different ways of learning and teaching. Specifically, the UN Goal 4: Quality Education emphasises inclusive and equitable education, defining it as

… a process of systemic reform embodying changes and modifications in content, teaching methods, approaches, structures and strategies in education to overcome barriers with a vision serving to provide all students of the relevant age range with an equitable and participatory learning experience and environment that best corresponds to their requirements and preference (United Nations, General Comment No. 4, 2016, p.4).

Therefore, the iPEAR project embraces students’ needs and personal approaches to learning. Before presenting the pedagogy, briefly defining the terms peer learning and Augmented reality is helpful.

There are many explanations for peer learning, including different roles and responsibilities. Boud, Cohen, and Sampson (1999, 2014) define it as” the use of teaching and learning strategies in which students learn with and from each other without the immediate intervention of a teacher (1999, p. 413). It is also a form of reciprocal peer learning. Wessel (2015, p.14) says that when students engage in P2P, they can learn practical skills to give critical feedback and thus teach effectively. Palmer and Blake (2018) note in the Harvard Business Review that peer-to-peer learning fits naturally with how we naturally acquire new skills with the Learning Loop: People gain new skills best in any situation that includes all four stages of what we call the Learning Loop: gain knowledge; practice by applying that knowledge; get feedback and reflect on what has been learned. Peer-to-peer learning encompasses all of these.

Augmented Reality (AR) connects with the help of technology and visual information in the real world. Its technical means include Multimedia, 3D modelling, Real-time Tracking and Registration, Intelligent Interaction, Sensing, and more. Its principle complements computer-generated virtual information, such as text, images, 3D models, music, video, etc., to the real world (Hu Tianyu et al., 2017) and people.

AR technologies can be divided into several categories. In the iPEAR project, we focus on the following three: Mobile apps are a common way to experience AR through a mobile device (phone or tablet). The user opens the device camera and sees the real world with digital augmentations added to it (e.g., by recognising a marker/QR code or the phone’s location). The quality of the experience heavily relies on the quality of the camera, the quality of the visuals and the device’s processing power. WebAR lets users view the AR experience using their browser (laptop or mobile device). WebAR experiences are available for laptops through the webcam. AR Head Mounted Displays (HMDs), designed by, e.g., Microsoft, Magic Leap and Apple, allow the users to access immersive, high-quality AR content, often with natural interfaces (such as using hand gestures for input) (iPEAR resources, 2023).

Having already discussed the new roles of the so-called ‘good university’, the importance of pedagogy and the definitions of peer learning and augmented reality, the next step is to discuss the elements of the pedagogy that need to be considered before using the technology.

5.1. The iPEAR elements of pedagogy

The framework of iPEAR was designed as an experimental approach that was tested and elaborated in the co-funded Erasmus KA2 project in higher education. The initiative aims to join social learning through peer-to-peer task designs (Mazur, 1997) and visualisation as a form of microlearning widely used in vocational training and marketing via AR tools. The AR tools used were free versions of mobile apps, except for a case study from the IMTEL lab in Norway that uses Microsoft HoloLens. During the research process, two more elements were derived from the surveys with students, the interviews with educators, and the literature in the field. They need to better understand the roles (social and ethical) of visuals or visual content creation in learning (visual literacies and media) and gradually build a peer feedback culture (critical thinking). This peer feedback perspective is based on students; previous experiences and cultural background, but it could be reinforced with rewards or incentives initiated by educators. This sharing attitude could make courses more inclusive and help students take more responsibility for their studies and the growth of the learning community. The pedagogy is formulated within the boundaries of informed grounded theory that combines research analysis with updated literature reviews. The approaches based on Informed grounded theory are in a never-ending evolution as they need frequent revisions by the literature and new studies.

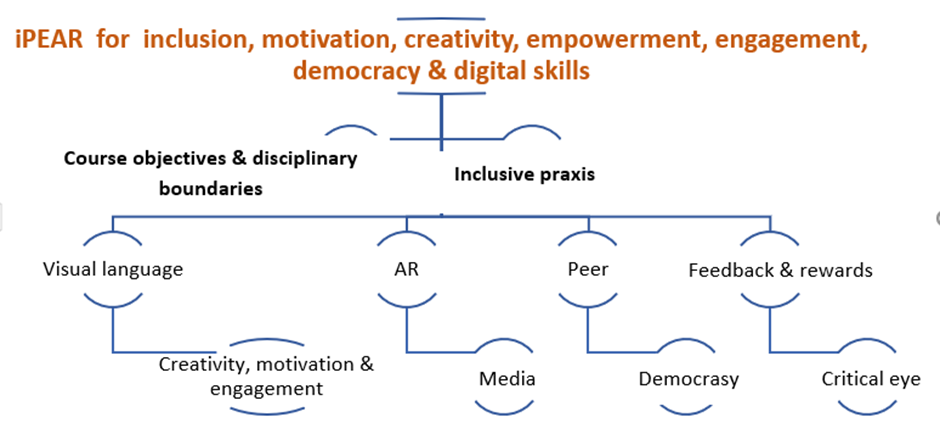

As derived from the literature (chapters 2 & 3) and research findings in the frame of informed grounded theory (chapter 4), inclusive peer learning with augmented reality has much to offer the students. They could be more creative, motivated and engaged with the assignments, and there is also the potential to be empowered, especially when they are content creators. It cannot be ignored that such activities may be labour-intensive and costly, especially when the institutions cannot offer equipment and training. As described in figure 6, the iPEAR approach could serve course observers, emphasise inclusive praxis, embrace the visual language students prefer while working with their peers, and exchange feedback and gain knowledge and skills. When creatively engaged, the students could learn how to use new tools, work in a participatory culture and develop a critical eye for their learning process. The motto of iPEAR is: ‘Connect people, design technology-enhanced learning (TEL) pedagogy skills and content will emerge’.

5.1.1 Theoretical framework

Philosophically speaking, education could be considered a path to self-efficacy via social learning theories. The iPEAR framework is based on the work of the psychologist Albert Bandura (1971 & 1977). Students must be lifelong learners to address the demands of the job market and search for personal fulfilment via a learning process to unlearn old patterns of thinking and obsolete digital skills and replace them with new competencies, attitudes, and roles- while maintaining well-being. Albert Bandura (1977) argues that learning is not an isolated act, but we can learn by interacting with others.

Social learning theory, originated by Albert Bandura, proposed that learning occurs through observation, imitation, and modelling and is affected by factors such as attention, motivation, attitudes, and emotions. The theory embraces the interaction of environmental and cognitive elements that affect people’s learning. Bandura’s social learning theory explains that learning can also occur simply by observing the actions of others. In the same train of thought, Ahn, Hu and Vega (2020) claim that social and cognitive processes involved in role modelling tend to be ignored. Their work provides an overview of role model research in education, detailing the researcher’’ focus and emphasis on identifying aspects of role model effectiveness. They focus on role models’’ attentional, cognitive, and motivational processes and ask for more research on imitation in education.

To further develop the pedagogical frame, it is categorised into four elements and broken down into guidelines and a checklist to make the iPEAR approach easy to use.

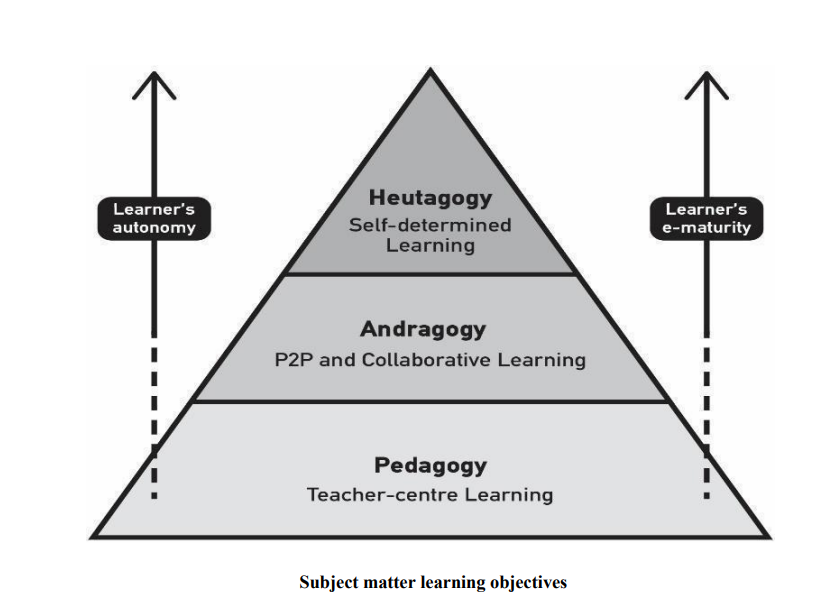

5.1.2 Students’ level of autonomy and e-maturity (digital skills)

The first step for educators before adapting the iPEAR model is to identify the students’ level of autonomy. For instance, undergraduates and postgraduates have different skills and needs for self-directed learning, and a survey or student discussion could help educators determine their preferences and needs. In many cases, though, it is not feasible to analyse the target audience’s level of autonomy, which is why students need more options to choose from within courses. This is the definition of inclusiveness illustrated above by the UN and adopted by the iPEAR pedagogy.

To further explain, the science of pedagogy targets discovering the level of independence and digital skills before designing learning objectives to design more choices for learning. For instance, learners from different cultural backgrounds may be accustomed to teacher-centred approaches. The so-called

‘Sage on the stage’ is responsible for all the choices of assignments and lectures to target learning goals. This target group may not be well-prepared for eLearning or collaborative praxis.

Conversely, educators could be described as facilitators- the ‘Guide on your side’ or fellow travellers for postgraduate or Ph.D. candidates. Thus, the educator’s roles change according to the target group’s characteristics: children or adults, cultural factors, and previous experiences. It is important to note that educators could show their students emancipatory and inclusive approaches, step by step, with rewarding inclusivity and social interaction.

The baseline of figure 7 is the learning objectives within the disciplinary boundaries. The incremental levels show the transition from pedagogy to andragogy, then to heutagogy as self-efficacy and awareness The final destination is heutagogy. Students need time and support to reach the top level. It depends on the educator’s priorities to show the importance of inclusiveness and collaboration even when students need a teacher-centred approach. McAuliffe, Hargreaves, Winter and Chadwick (2008) recommend:

- Knowing how to learn and unlearn is essential

- Educators emphasise the learning process rather than content

- Learning goes beyond specific discipline

- Learning goes through self-chosen and self-directive action

P2P is an intermediate level that assists students in enhancing their critical thinking and collaboration skills, moving away from teacher-led activities. The educators could consider their target audience level regarding learner autonomy and e-maturity to use digital tools such as AR and disciplinary priorities and boundaries. Sometimes, the educators may choose to use a combination for different pedagogical levels. For example, they could adopt a more teacher-centred approach, illustrating the use of AR and then orchestrating a collaborative P2P assignment for implementing the iPEAR pedagogy to serve learning outcomes. Inclusive values must be explicitly stated and rewarded while sharing equally feedback, devices, and work. In praxis, inclusiveness means that students can share devices, teach each other, resolve conflicts democratically and get rewarded by their peer assessments and educators’ criteria.

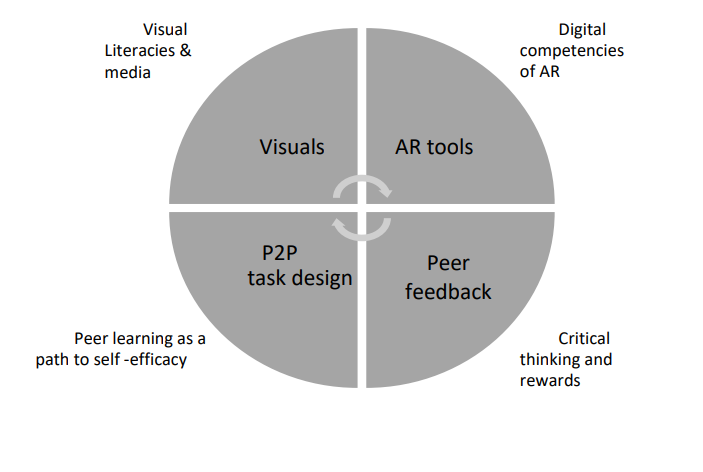

Figure 8 shows the iPEAR Schema’s purpose is to visualise the pedagogical framework. It is separated into four sections in constant interaction: Visuals (visual literacies and media), AR tools (digital competencies), P2P tasks design, and peer feedback culture (rewarding collaboration and critical thinking).

The first element of the iPEAR pedagogy is visuals or visual Literacy. The following definition comes from the 2011 ACRL Visual Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education:

Visual Literacy is a set of abilities that enables an individual to effectively find, interpret, evaluate, use, and create images and visual media. Visual literacy skills equip learners to understand and analyse the contextual, cultural, ethical, aesthetic, intellectual, and technical components of producing and using visual materials. A visually literate individual is both a critical consumer of visual media and a competent contributor to a body of shared knowledge and culture. (ACRL Board of Directors. 2011; Association of College and Research Libraries, 2022).

The term visual literacies was used in the plural to connotate the use of different forms of visual produced by various media, from comics and animation to video and avatars, to name a few. Learners and teachers could consider the role and potential of visuals in education, especially from a technology-enhanced learning perspective. Visual literacies could also be used in the plural (because of the abundance of visual media and visual creations) and be part of professional training. The visible capital has much to offer. Educators must know that visuals disseminate meaning faster, but different audiences can interpret it differently. In other words, visual experiences, aesthetics, and ethics are crucial in understanding visual media and its products. Thus, educators and students could spend some time discussing the role of visual literacies, pros, and cons before the assignment. The standards of visual Literacy could be equally helpful, as explained below.

The ARCL (Association of College and Research Libraries, 2022) have studied visual Literacy for over 12 years. It states that in an interdisciplinary, higher education environment, a visually literate individual can:

- Determine the nature and extent of the visual materials needed

- Find and access required images and visual media effectively and efficiently

- Interpret and analyse the meanings of images and visual media

- Evaluate images and their sources

- Use images and visual media effectively

- Design and create meaningful images and visual media

- Understand many ethical, legal, social, and economic issues surrounding creating and using images and visual media.

Thus, the educators could be trained on visual approaches and media within the disciplinary framework to understand the visual landscape better and what needs to be created for the course. How could they communicate and share visuals? What kind of copyrights and ethical questions could they pose, and what ethical considerations should they consider? Regarding the level of autonomy (pedagogy, andragogy), learners may ask for a different level of control and independence. In peer learning, a rubric with critical questions may trigger attention to the criticality and ethical implications of the visuals – conscious and unconscious bias. It is crucial to note that audio files could be added with AR tools, but there is always a visual marker that triggers the AR experience.

The second pillar is AR tools (digital skills). Visual Literacy is part of AR technologies that aim to extend realities with information. Educators must invest significant time in choosing technologies to serve the disciplinary requirements, and they must rely on the assistance of instructional designers or learning technologists. Educators could choose from a variety of AR apps that are marker-based (e.g., recognising a QR code), markerless (scanning the room) or location-based (relying on the device’s GPS location, such as Pokémon Go). They could also consider different hardware platforms, from regular mobile phones to more elaborated HoloLens 2 (Augmented reality glasses). Unfortunately, educators face many challenges, such as engineers’ technical jargon, complicated tutorials, and lack of training – complicating AR adoption in Higher Education.

The third pillar is P2P task design (according to the level of students’ autonomy). The students need to fully understand why they get involved in an assignment, what they could get out of it and the usefulness of using technology. The students’ and teachers’ explanations may differ (Pask, 1975). The peers may find ways to instruct others more gradually or vividly because they have done so for themselves. For educators, explaining something they know very well could be automatic and may break down information into bigger chunks than the students can digest (Mazur,1997).

The P2P task design using AR heavily depends on AR’s affordances for supporting remote or co-located collaboration. This includes mutual awareness (e.g., of peers represented by virtual avatars, as well as of shared spaces and objects such as anatomical models), communication (e.g., through voice chat and gestures) and mutual interaction and sharing (e.g., manipulating shared objects) (Radu et al., 2021). The task design might differ depending on whether the peer-to-peer interaction is remote or collocated: for example, remote peers need to be provided with some form of communication, such as voice chat, which is unnecessary for co-located ones. Co-located peers depend on consistent anchoring of shared models (e.g., a virtual house model) in the physical space, which is less relevant for remote learners. Both remote and co-located peers need to maintain awareness of their peers’ actions (e.g., by pointers in the shared workspace).

The fourth part is the peer feedback culture, inclusive praxis, and rewards before, during, and after the designed activity. In creating a culture of constructive feedback, the students could create social netiquette and a growth mindset initiative. Social netiquette refers mainly to productive ways to offer feedback without judgement and help everyone in the peer group participate. Educators’ feedforward and rubrics could help students imitate the example for providing constructive feedback to peers. A growth mindset embraces mistakes as a way of knowing and regards learning as a life-long process. In plain words, a growth mindset is a concept in which skills and performances can be enhanced, and research shows that students’ growth mindsets can predict higher achievement, well-being, and inclusive praxis (Dweck & Yeager, 2021). It is also crucial to reward those students who teach others, share their devices with others, enhance inclusive values and act as good models for others to imitate.

During the two-meter society of the pandemic, the P2P approach offers a supportive mechanism against alienated distance courses based on lectures (Vergroesen, 2020). Students were urged to co-create content, share personal experiences, analyse, evaluate, and retain knowledge while working with ‘class partners’. Peers were the cure against the passive learning approach (online lecturing) and isolation of the pandemic. Research (Cohen, Kulik, Kulik, 1982; Freeman et al., 2014) showed that students could pass the courses and deepen their understanding if they worked with peers. Student-led assignments, collaborative reviews, and dialogues in breakout sessions are peer-to-peer active learning approaches that have become popular, especially during lockdowns. Educators and students enjoy personalised instruction from their peers and take more responsibility for their personal growth (Vergroesen, 2020).

Peer feedback could be a reliable source of scalable learning under three conditions:

- The students should be offered rubrics to explain the role of collaboration and inclusive etiquette of interactions.

- The activity should be designed with appropriate difficulty or different options that accommodate students’ needs.

- The students are willing and motivated to teach each other (rewards for peer collaboration).

Students need a rewarding system to work with peers to enhance motivation. Some educational systems concentrate on collaborative praxis from a young age, while others are more teacher-led and competitive. Therefore, students must understand why they must commit to the task, work, and teach each other as a form of inclusive and democratic engagement. The reward needs to be noticeable: grades, more choice, student agency, or peer recognition that promotes mutual respect. Parchoma (2005) and Pentland (2014,2020) consider rewards as the social glue that builds excellent teamwork and boosts motivation and engagement. Pentland’s studies at MIT-humans dynamic lab- (2014) proved that better performance and innovation are the product of effective and democratic collaboration rather than the high intellect potential of a few. If using AR technologies, the affordances of AR will also influence modes for giving and receiving feedback and rewards.

5.3 Basic guidelines

Based on the iPEAR scheme described above, we developed basic guidelines for educators.

Educators must

- be aware of the digital divide (ensure that the tools are inclusive and everyone has acquired the devices and the know-how). This could be done with training (by educators or peers) and sharing approaches. Sharing mobile phones with people they cannot afford to have.

- allow their students to form teams. Research shows that when students choose their peers, there is better collaboration (Zhang, Ding, & Mazur, 2017)

- design the task within the optimal difficulty level that serves the learning outcomes.

- explain copyright issues and visual ethics

- provide peer feedback templates whenever needed

- be cautious of visual culture (the impact of visuals in everyday life as the source of information, aesthetics, and learning).

- promote student agency in designing the task according to the disciplinary boundaries.

- talk about group dynamics: avoiding domineering behaviours (all voices heard). It is essential to note that the roles and abilities could be similar or different according to the P2P task design scenarios.

- enhance inclusive praxis for P2P instruction (facilitate learning for those with learning challenges with visual material) and update the digital competencies.

A checklist may offer additional help in planning a course or a single lesson using the iPEAR scheme:

✔ Technical issues – digital skills for AR

- Am I fully aware of the AR tools I will use?

- Do I have an alternative plan if, for some reason, the AR tool is not working for all mobile phones?

- Have I designed a pilot assignment to ensure all students are on the same page (technical skills)?

- Have the students the digital skills to work in an iPEAR scenario?

- Could students work remotely?

- Could students work synchronously and asynchronously?

- Would the chosen software and software support the selected work mode (remote/co-located, synchronous/asynchronous)?

✔ Visuals – content creation and media

- Have the students discussed the role of visuals in learning?

- Are the students informed of the visual data copyrights and ethics?

- Are students aware of visual media to use?

- Is the visual quality of media sufficient for the purpose?

- Is there visual support for P2P processes, such as peer avatars, pointers indicating user activities, and other ways of maintaining awareness of shared virtual workspace?

✔ Peer learning task design

- Have the students had prior collaborative learning experiences?

- Are the students satisfied with collaborative learning?

- Are the students able to produce visuals for the learning outcomes?

- Are the students able to use the specific AR tools?

- Are the students aware of the inclusive nature (Sharing ideas, devices and assessment) of peer learning?

- Have the students had choices in the visual by-product?

- Could the students choose their peers?

- Could the students have different roles?

- Does the peer learning task design consider AR technology’s affordances?

✔ Peer feedback culture

- Is the iPEAR assignment rewarding (grades) and motivational (creative and critical thinking) for the students?

- Could students, according to their level of autonomy, assess each other’s work?

- Have I provided assessment criteria?

This checklist has been developed to offer orientation. It does not have to be followed in every single point.

5.4 Conclusion, limitations, and future directions

The iPEAR research evaluated the holistic pedagogical design. The study of holistic pedagogy included 22 interviews with educators from Greece, Norway, and Germany and 214 survey data from their students. The research report will be published as a compendium of best practices (www.i-pear.eu) and presented in the MOOC in April 2023. P2P learning could promote lifelong learning, communication skills, and a culture of inclusion and constructive feedback. AR adopts the visual language of the internet and enhances the digital skills needed. The findings showed that the two combined elements could promote students’ engagement, motivation and empowerment while mirroring the social value of inclusiveness. At the same time, while one of the primary motivations for the project has been the pandemic and the corresponding need for inclusive remote P2P learning, most of the studies in this project are based on co-located peer learning with AR. This is partly due to the technical limitations and logistical challenges of enabling efficient and user-friendly remote peer-learning sessions. More research is needed to adopt collaborative AR for remote P2P learning.

The instructional design has limitations. The most significant barrier is the lack of training and bridging the gap between research and praxis. The iPEAR pedagogy may be less effective for younger students or those from a cultural background with no collaborative assignment or inclusive approaches. The cost of technology and the internet is a significant barrier that cannot be ignored. As technology advances, AR tools become more user-friendly and cost-effective for educators. Billinghurst (2021) claims that the most significant limitations of adopting AR are social and ethical issues related to using visuals and human interaction limits.

With so many students dropping out of school, growing marginalisation of people experiencing poverty in society, psychological and physical well-being in danger, and so many modern jobs requiring advanced digital skills, there has never been a more critical time to figure out new pedagogical paths. The post-Covid era calls for innovative and resourceful ways to promote inclusiveness, social learning and digital skills working harmoniously together to empower students as lifelong learners caring for their peers.