Chapter 3: Using Active Reading Strategies

Introduction to Chapter 3

Effective readers are active readers. They actively interact with the text while reading. This chapter will help you explore the following questions:

- What do strong readers do when reading academic material?

- How can students make the best use of their time when reading?

- What are some reading strategies students can use to understand readings, to remember key ideas, and to respond to the material they will be required to read in college?

This chapter will help you practice strategies to read effectively and efficiently. You will learn how to actively read by annotating, answering pre-reading questions, doing quick research, and discovering what a text has to say. The ultimate goal is to get the most out of your reading in college so that you can confidently participate in class discussions or write about the texts you have read.

3.1 What Is Active Reading?

Does the following sound familiar? You have had a full day of classes, so you go to the gym to get in a workout. Afterward, you meet a friend who suggests going out for a quick bite; you get back to your room around eight o’clock and settle in to work on your reading assignment, a chapter from your sociology text entitled “Stratification and Social Mobility.” You jump right in to the first paragraph, but the second paragraph seems a bit tougher. Suddenly you wake up and shake your head and see your clock says 11:15 p.m. Oh no! Three hours down the drain napping, and your book is still staring back at you at the beginning of the chapter, and now you have a crick in your neck.

Now, picture this: You schedule yourself for a series of shorter reading periods at the library between classes and during the afternoon. You spend a few minutes preparing for what you are going to read, and you get to work with pen and paper in hand. After your scheduled reading periods, by 5:30 p.m. you have completed the assignment, making a note that you are interested in comparing the social mobility in India with that in the United States. You reward yourself with a workout and dinner with a friend. At 8 p.m., you return to your room and review your notes, feeling confident that you are ready for the next class.

The difference between these two scenarios is active reading. Active reading is a planned, deliberate set of strategies to engage with text-based materials with the purpose of increasing your understanding. This is a key skill you need to master in college. Along with listening, it is the primary method for absorbing new ideas and information in college. But active reading also applies to and facilitates the other steps of the learning cycle; it is critical for preparing, capturing, and reviewing, too.

Watch the following video to learn more about active reading:

Check Your Understanding 3.1: Active Reading

Assess your present knowledge and attitudes about reading. On a sheet of paper, describe whether you agree or disagree with the following statements:

- I am a good reader and like to read for pleasure.

- I feel overwhelmed by the amount of reading I have to do for classes.

- I usually understand what is written in textbooks.

- I get frustrated by difficult books.

- I find it easy to stay focused on my reading.

- I am easily bored reading for classes.

- I take useful notes when I read.

- I can successfully study for a test from the notes I have taken.

- I use a dictionary when needed while reading.

- I have trouble reading long passages on the computer screen.

Think about how you answered the questions above. Be honest with yourself. On a scale of 1 (poor academic reading skills) to 10 (strong academic reading skills), how would you rate your level of academic reading at this time?

Go to the end of this chapter to the section “Answers for the Check Your Understanding Activities” to read more.

3.2 Get Started: Read Efficiently

Sit down (in your ideal setting and at your ideal time, if possible) and prepare to read. Do whatever you need to do to minimize distractions during your reading session. (This may include putting your smartphone and other technology on silent or in another room.) Have paper and pencil available to take notes.

Read carefully, stopping and rereading sections you do not quite understand. Be sure to look up words you are not familiar with. This is important! Most of us are good contextual readers; that is, we can usually figure out what an unfamiliar word means based on the content around it. But in your academic, college-level writing, every word is important, and some words carry enough power to change the meaning of a sentence or to launch it into a whole new level of detail. Also, some words have different meanings in the academic setting than in our more casual everyday lives. When you hit a word you do not know, stop, make a note in the margin (or on a piece of paper), and look it up. If you find that stopping to look up individual words is too distracting, you can make a list of all the unknown words you run into and then look them all up when you have finished reading.

Keep reading until you are done. Do not be distracted. If you begin to feel fidgety, stop, get up, and take a five-minute break. Then get back to your reading. The more you read, the stronger your habit will grow, and the easier reading will be.

3.3 Annotate and Take Notes

As children, most of us were told never to write in books, but now that you are a college student, your instructors will tell you just the opposite. Writing in your texts as you read—which is called annotating—is encouraged! It is a powerful strategy for engaging with a text and entering into a discussion with it. You can jot down questions and ideas as they come to you. You might underline important sections, circle words you do not understand, and use your own set of symbols to highlight portions that you feel are important. Capturing these ideas as they occur to you is important, for they may play a role in not just understanding the text better but also in your college assignments. If you do not make notes as you go, today’s great observation will likely become tomorrow’s forgotten detail.

Important note: most college and university bookstores approve of textual annotation and do not think it decreases a textbook’s value. In other words, you can annotate a college textbook and still sell it back to the bookstore later on if you choose to. Note that I say most—if you have questions about your own school and plan to sell back any textbooks, be sure to ask at the bookstore before you annotate.

If you cannot write on the text itself, you can accomplish almost the same thing by taking notes—either by hand (on paper) or e-notes. You might also choose to use sticky notes to capture your ideas—these can be stuck to specific pages for later recall.

Many students use brightly-colored highlighting pens to mark up texts. These are better than nothing, but in truth, they’re not much help. Using them creates big swaths of eye-popping color in your text, but when you later go back to them, you may not remember why they were highlighted. Writing in the text with a simple pen or pencil is always preferable.

When annotating, choose pencil or ball-point ink rather than gel or permanent marker. Ball point ink is less likely to soak through the page. If using erasable pens, test in an inconspicuous area to make sure they actually erase on that paper.

What about e-books? Most of them have on-board tools for note-taking as well as providing dictionaries and even encyclopedia access.

Many students also like to keep reading journals. A good way to use these is to write a quick summary of your reading immediately after you have finished reading. Capture the reading’s main points and discuss any questions you had or any ideas that were raised. Include the author and title when writing in a reading journal.

To use active reading with your college reading assignments, follow these steps:

- Double-underline what you believe to be the topic or thesis statement in the article or chapter. The thesis statement is one or two sentences that summarizes the article or chapter’s main point and tells what it’s about. The thesis statement can occur anywhere in the article—even near the end.

- As you read, underline points that you find especially interesting.

- Make notes in the margins as ideas occur to you. After each paragraph or section, write a margin note that describes the author’s main point for this paragraph or section. Make sure to write the main point in your own words.

- Write your reactions in the margins. If you can relate to the ideas, explain why. If the ideas remind you of another text or a real-world experience, explain why. Try to capture your thinking through writing so that you will remember the ideas later.

- Write question marks in the margin where questions occur to you, and make written margin notes about them, too.

- Circle all words you don’t understand. Then look them up! (Dictionary.com is a good online dictionary and even pronounces words so you will know how they sound.) Write down the definitions.

- When you are finished reading, write a quick summary—several sentences or a short paragraph—that captures the article’s main points.

Check Your Understanding 3.3: Annotation

Print a copy* of the New York Times article, “Are We Loving Our National Parks to Death?”

Pre-read the article to gather some first impressions. (If you need help with pre-reading, go back to the previous chapter.) Then read the article completely, annotating as you go.

*If you aren’t able to print a hard copy, carry out the following instructions using a piece of paper and a pen or pencil.

- Double-underline what you believe to be the topic or thesis statement in the article.

- As you read, underline points that you find especially interesting.

- Make notes in the margins as ideas occur to you.

- Write your reactions in the margins.

- Write question marks in the margin where questions occur to you, and make written margin notes about them, too.

- Circle all words you do not understand. Then look them up! Write down the definitions.

- When you are finished reading, write a quick summary that captures the article’s main points.

Go to the end of this chapter to the section “Answers for the Check Your Understanding Activities” to read more.

3.4 Samples of Annotation Processes

Annotations should not consist of JUST symbols, highlighting, or underlining. Successful and thorough annotations should combine those visual elements with notes in the margin and written summaries; otherwise, you may not remember why you highlighted that word or sentence in the first place.

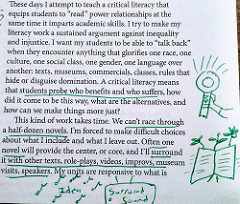

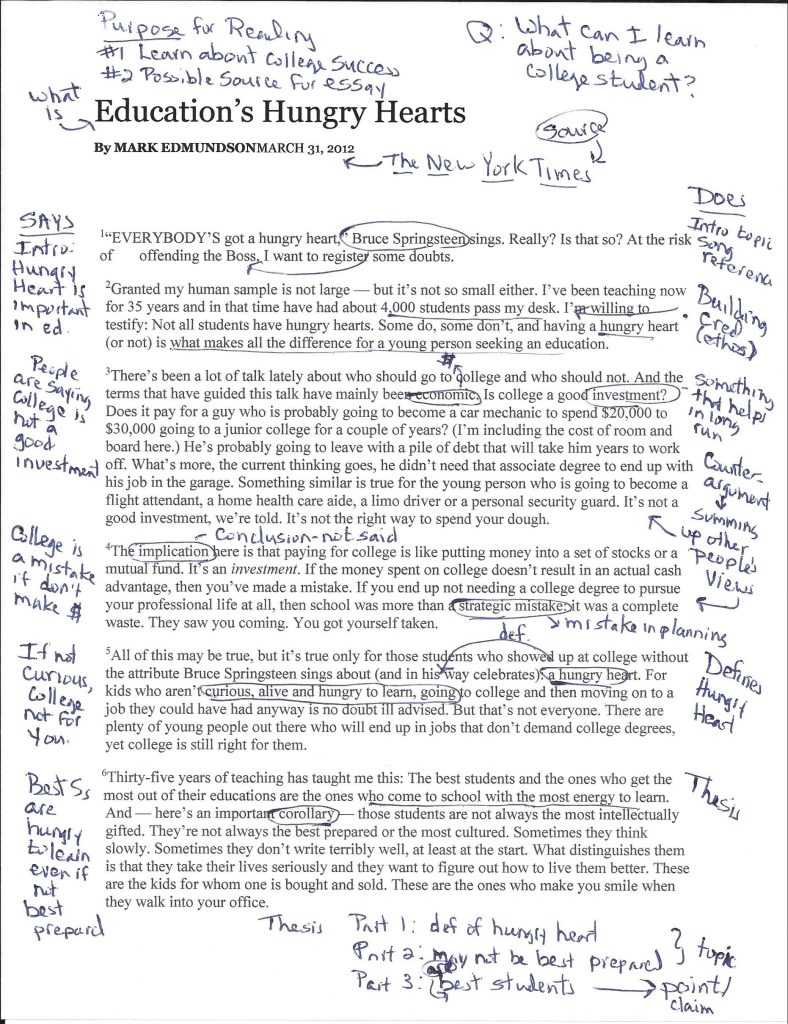

Notice that in the image below that presents sample annotations, the student has written marginal notes on the left that summarize what the author is saying or describing. On the right side of the page, the student then describes what the paragraphs or doing, or how they are functioning in the piece. The student has also circled and defined complex words. Rather than just underlining at random, the student is actively reading by marking the text for specific reasons.

Watch this video to see another example of how to annotate.

3.5 Answer Pre-reading Questions

After annotating the text you are reading, look back at the pre-reading questions you developed for the headings and subheadings (in the pre-reading process). As you read and annotate, you should be able to answer the questions you developed. Write your answers in the margins of the text or on a separate sheet of paper. You may find that you need to revise your questions while reading.

3.6 Do Quick Research

As you read, you might run into ideas, words, or phrases you do not understand, or the text might refer to people, places, or events you are unfamiliar with. It is tempting to skip over those and keep reading, and sometimes that actually works.

But keep in mind that when you read something written by a professional writer or academic, they have written with such precision that every word carries meaning and contributes to the whole. Therefore, skipping over words or ideas could change the meaning of the text or leave the meaning incomplete.

When you are reading and come to words and ideas you are unfamiliar with, you may want to stop and take a moment to do a bit of quick research. Google is a great tool for this—plug in the idea or word and see what comes up. Keep on digging until you have an answer, and then, to help retain the information, take a minute to write a note about it.

3.7 Discover What a Text Is Trying to Say

All texts—whether fiction or nonfiction—carry layers of information, built one on top of the other. As we read, we peel those back—like layers in an onion—and uncover deeper meanings.

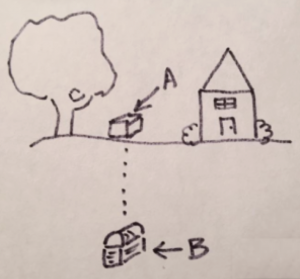

Take a look at Figure 1 to the right. This figure can be used to explain the concept of “deeper meaning.” All texts and stories have surface meaning. In the sketch, this is represented by all the things we see above ground: the tree, the house, and the box (A), along with whatever is in it—even though the box may be closed, anyone who walks by can see it and explore it. These items are concrete and obvious. In “Goldilocks and the Three Bears,” for example, the surface story is about a little girl who goes for a walk in the forest, wanders into the bears’ home, gets into their belongings, and is frightened off.

But stories and essays also have deeper, hidden meanings. In Figure 1, there is a buried treasure chest (B) deep underground, waiting to be discovered and opened. Texts are much the same—they each contain obvious, surface level meanings, and they each contain a buried prize as well. What is the deeper meaning in “Goldilocks”? Most fables and fairy tales were designed to teach, warn, or scare. Perhaps the author wants us to think about what happens when we invade people’s privacy. Or maybe it is about the drawbacks of curiosity. What do you think?

When working with a text, be aware of everything that is happening within it—almost as if you are watching a juggler with several balls in the air at one time:

- Consider the characters or people featured in the text, their dialogue, and how they interact.

- Be aware of the plot’s movement (in a fictional story) or the topic development (in a nonfiction story or essay) and the moments of excitement or conflict as the action rises and falls.

- Look for changes in time—flashbacks, flash-forwards, and dream sequences.

- Watch for themes (ideas that occur, reappear, and carry meaning or a message throughout the piece) or symbols (objects or ideas that stand for or mean something else; these carry meaning that we often understand quickly without thinking about it too much).

- Examples of themes: coming of age, redemption, the nature of honesty, conflict, sacrifice.

- Examples of symbols: full moon (typically suggests mystery), dark forest (danger or the possibility of being lost), white flag (surrender), a path or road (journey).

As you read, always look for both surface meanings and those buried beneath the surface, like treasure. That is the fun part of reading—finding those precious hidden bits, waiting to be uncovered and eager to make your reading experience richer and deeper. Even if you just scratch the surface, you will learn more.

Answers for the Check Your Understanding Activities

3.1: Active Reading

If you gave yourself a low score for this exercise (a score of 1 to 5), do not worry. This e-book will help you with strategies to assist you with academic reading.

If you gave yourself a high score (a score of 7 to 10), you might think about what has worked well for you when reading academic material. Think about how you might continue to strengthen your academic reading skills.

3.3: Annotation

Again, there is no right or wrong answer for this activity—simply a chance for you to practice annotation.

Here is a sample of what a short summary of this article might look like. Notice that the author and title of the article are mentioned in the first sentence:

In “Are We Loving Our National Parks to Death,” Dayton Duncan raises questions about the effects of millions of visitors on our national park lands. He talks about our parks’ origins and contrasts the parks’ early years with their condition now. He points at problems that include lack of camping space, roads in disrepair, and a general overcrowding, and he discusses ideas for limiting impacts—which may mean limiting visitors. He also brings up interesting points about the way climate change is affecting many of our national parks and forests. Ultimately, he asks the public for help in championing the parks with money and support.

Licenses and Attributions

CC Licensed Content, Shared Previously:

- Introduction to Chapter 3 was authored by: Pamela Herrington-Moriarty. License: CC BY-NC 4.0

- Section 3.1 was adapted from Chapter 5: Reading to Learn, Success in College; authored by the University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing through the eLearning Support Initiative. License: CC BY-NC 4.0

- Sections 3.2, 3.5, 3.6, and 3.7 were adapted from Part 1: Working with Texts, The Word on College Reading and Writing; authored by: Monique Babin, Carol Burnell, Susan Pesznecker, Rose Rosevear, and Jaime Wood. License: CC BY-NC 4.0

- Section 3.3 was adapted from Annotate and Take Notes by Carol Burnell, Jaime Wood, Monique Babin, Susan Pesznecker, and Nicole Rosevear, license: CC BY-NC 4.0.

- Section 3.4 was adapted from Critical Reading by Elizabeth Browning, Karen Kyger, and Cate Bombick license: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License and includes “Sample Says/Does Annotation,” Karen Kyger, Howard Community College, CC-0.

Video Content

- “What is active reading” by OnDemandInstruction