Chapter 5: Reading Textbooks

Introduction to Chapter 5

In the majority of your college classes, you will be asked to read textbook chapters. Students may think that they can just simply read a textbook chapter and move on, but when it comes to applying the information to an assignment or a test, it is important to actively read and critically think about the material. If you do not actively read material you are assigned, you will likely forget what you have read in the following days or weeks after reading.

5.1 Anatomy of a Textbook

Good textbooks are designed to help you learn, not just to present information. They differ from other types of academic publications intended to present research findings, advance new ideas, or deeply examine a specific subject. Textbooks have many features worth exploring because they can help you understand your reading better and learn more effectively. In your textbooks, look for the elements listed in the table below.

Table 5.1 Anatomy of a Textbook

| Textbook Feature | What It Is | Why You Might Find It Helpful |

|---|---|---|

| Preface or Introduction | A section at the beginning of a book in which the author or editor outlines its purpose and scope, acknowledges individuals who helped prepare the book, and perhaps outlines the features of the book. | You will gain perspective on the author’s point of view, what the author considers important. If the preface is written with the student in mind, it will also give you guidance on how to “use” the textbook and its features. |

| Foreword | A section at the beginning of the book, often written by an expert in the subject matter (different from the author) endorsing the author’s work and explaining why the work is significant. | A foreword will give you an idea about what makes this book different from others in the field. It may provide hints as to why your instructor selected the book for your course. |

| Author Profile | A short biography of the author illustrating the author’s credibility in the subject matter. | This will help you understand the author’s perspective and what the author considers important. |

| Table of Contents | A listing of all the chapters in the book and, in most cases, primary sections within chapters. | The table of contents is an outline of the entire book. It will be very helpful in establishing links among the text, the course objectives, and the syllabus. |

| Chapter Preview or Learning Objectives | A section at the beginning of each chapter in which the author outlines what will be covered in the chapter and what the student should expect to know or be able to do at the end of the chapter. | These sections are invaluable for determining what you should pay special attention to. Be sure to compare these outcomes with the objectives stated in the course syllabus. |

| Introduction | The first paragraph(s) of a chapter, which states the chapter’s objectives and key themes. An introduction is also common at the beginning of primary chapter sections. | Introductions to chapters or sections are “must reads” because they give you a road map to the material you are about to read, pointing you to what is truly important in the chapter or section. |

| Applied Practice Elements | Exercises, activities, or drills designed to let students apply their knowledge gained from the reading. Some of these features may be presented via websites designed to supplement the text. | These features provide you with a great way to confirm your understanding of the material. If you have trouble with them, you should go back and reread the section. They also have the additional benefit of improving your recall of the material. |

| Chapter Summary | A section at the end of a chapter that confirms key ideas presented in the chapter. | It is a good idea to read this section before you read the body of the chapter. It will help you strategize about where you should invest your reading effort. |

| Review Material | A section at the end of the chapter that includes additional applied practice exercises, review questions, and suggestions for further reading. | The review questions will help you confirm your understanding of the material. |

| Endnotes and Bibliographies | Formal citations of sources used to prepare the text. | These will help you infer the author’s biases and are also valuable if doing further research on the subject for a paper. |

5.2 Set a Purpose for Reading

Now, before actually starting to read, try to give your reading more direction. Are you ever bored when reading a textbook? Students sometimes feel that about some of their textbooks. In this step, you create a purpose or quest for your reading, and this will help you become more actively engaged and less bored.

Start by checking your attitude: if you are unhappy about the reading assignment and complaining that you even have to read it, you will have trouble with the reading. You need to get “psyched” for the assignment. Stoke your determination by setting yourself a reasonable time to complete the assignment and schedule some short breaks for yourself. Approach the reading with a sense of curiosity and thirst for new understanding. Think of yourself more as an investigator looking for answers than a student doing a homework assignment.

5.3 Follow a Step-by-Step Process for Textbook Reading

Step 1: Prepare to Read

Before you start reading, survey or preview the text. When we survey, we get a broad overview of the text. Read the title, information about the author (if included), and information about the publisher. Look over the images including pictures, charts, graphs, and other visuals. Read the introduction. Try to get a sense of the major concepts that will be explored.

Next, reflect on what you already know about the subject. Even if you do not know anything, this step helps put you in the right mindset to accept new material.

Step 2: Develop Pre-reading Questions

After surveying the text and considering what you already know about the subject, it is important to develop questions to help guide your reading.

Many textbooks use headings and subheadings. Headings, if present, are the titles of the sections in a text. Headings will often give you clues as to the text’s content and show you how the subject has been divided into sections. If you are reading a textbook chapter with headings or subheadings, turn the title of each major section of the reading into a question and write it down in your notes.

If the text you are reading does not include headings or subheadings, look for key terms and important vocabulary, which are often formatted in bold or italics. Use the key terms and important vocabulary to develop questions.

Write these questions directly on the text or on a separate sheet of paper.

Step 3: Use a Method of Note Taking

Everybody takes notes, or at least everybody claims to. But if you take a close look, many who are claiming to take notes on their laptops are actually surfing the Web, and paper notebooks are filled with doodles interrupted by a couple of random words with an asterisk next to them reminding you that “This is important!”

In college, these approaches will not work. In college, your instructors expect you to make connections between class lectures and reading assignments; they expect you to create an opinion about the material presented; they expect you to make connections between the material and life beyond college. Your notes are your road maps for these thoughts. Do you take good notes?

There are various forms of taking notes, and which one you choose depends on both your personal style and approach to the material. Each can be used in a notebook, index cards, or in a digital form on your laptop. No specific type is good for all students and all situations, so we recommend that you develop your own style, but you should also be ready to modify it to fit the needs of a specific class or instructor. To be effective, all of these methods require you to listen read and to think.

When taking notes while reading textbooks, choose one of the following suggested note taking methods to help you create detailed, helpful notes.

Note Taking Option 1: Annotate the Text

When using printed material, it can be helpful to annotate, or write directly on the text. Annotation encourages close reading. When you annotate, it is as if you are entering into a discussion with the text. When you review your annotations after reading, they should remind you of the important concepts and your reactions to or questions about these concepts.

The purpose of marking your textbook is to make it your personal studying assistant with the key ideas called out in the text. Most readers tend to highlight too much, however, hiding key ideas in a sea of yellow lines. When it comes to highlighting, less is more. Think critically before you highlight. Your choices will have a big impact on what you study and learn for the course. Make it your objective to highlight no more than 10 percent of the text.

If you select the annotation note taking method when reading a textbook chapter, follow these steps:

- Double-underline what you believe to be the topic or thesis statement in the chapter. The thesis statement is one or two sentences that summarizes the chapter’s main point and tells what it’s about. The thesis statement can occur anywhere in the chapter—even near the end.

- As you read, underline points that you find especially interesting. Make sure to describe in writing why the text interests you.

- Make notes in the margins as ideas occur to you. After each paragraph or section, write a margin note that describes the author’s main point for this paragraph or section. Make sure to write the main point in your own words.

- After each section, use what you have read to answer the questions you developed. Write the answers in your own words.

- Write your reactions in the margins. If you can relate to the ideas, explain why. If the ideas remind you of another text or a real-world experience, explain why. Try to capture your thinking through writing so that you will remember the ideas later.

- Write question marks in the margin where questions occur to you, and make written margin notes about them, too.

- Circle all words you don’t understand. Then look them up! (Dictionary.com is a good online dictionary and even pronounces words so you will know how they sound.) Write down the definitions.

- When you are finished reading, write a quick summary—several sentences or a short paragraph—that captures the article’s main points

When reading material in textbooks, be especially alert to signals like “according to” or “Jones argues,” which make it clear that the ideas do not belong to the author of the piece you are reading. Be sure to note when an author is quoting someone else or summarizing another person’s position. Sometimes, students in a hurry to get through a complicated reading do not clearly distinguish the author’s ideas from the ideas the author argues against. Other words like “yet” or “however” indicate a turn from one idea to another. Words like “critical,” “significant,” and “important” signal ideas you should look at closely.

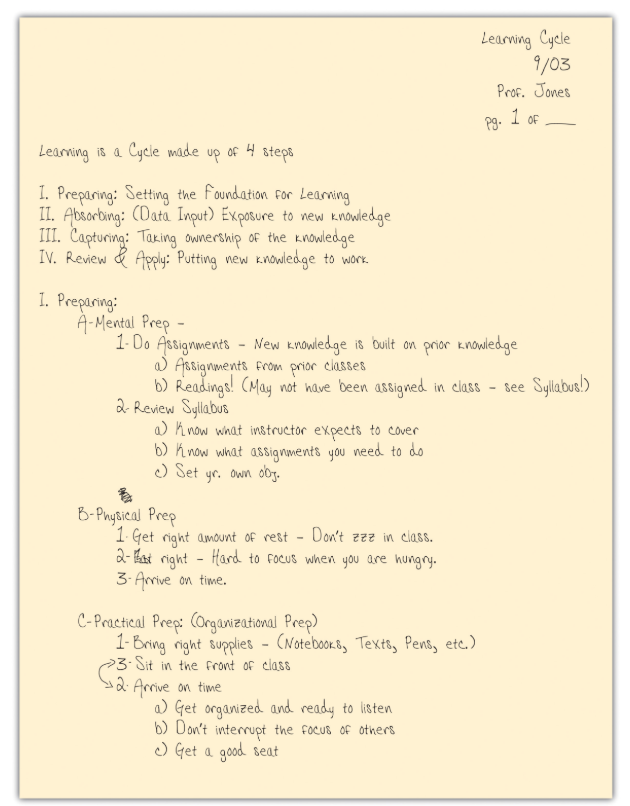

Note Taking Option 2: Cornell Notes

The Cornell method was developed in the 1950s by Professor Walter Pauk at Cornell University. It is recommended by most colleges because of its usefulness and flexibility. This method is simple to use for capturing notes, is helpful for defining priorities, and is a very helpful study tool.

The Cornell method follows a very specific format that consists of four boxes: a header, two columns, and a footer.

The header is a small box across the top of the page. In it you write identification information like the course name and the date of the class.

Underneath the header are two columns: a narrow one on the left (no more than one-third of the page) and a wide one on the right. The wide column, called the “notes” column, takes up most of the page and is used to capture your notes using any of the methods outlined earlier. The left column, known as the “cue” or “recall” column, is used to jot down main ideas, keywords, questions, clarifications, and other notes.

When using the Cornell note taking method, write your questions about the reading first in the left column (spacing them well apart so that you have plenty of room for your notes while you read in the right column). Write the answers to your questions in the right column. Also define the keywords you found in the reading.

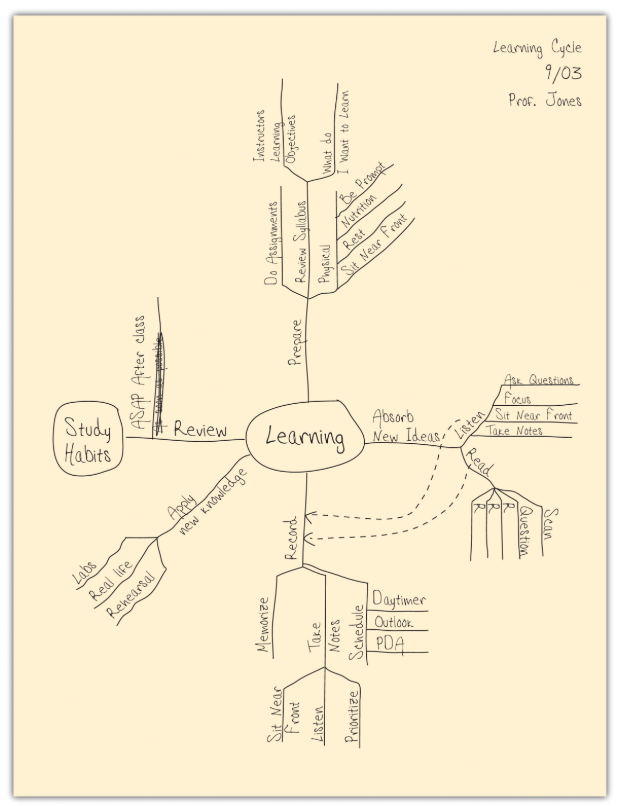

Note Taking Option 3: Concept Map

A concept map is a graphic method of note-taking that is especially good at capturing the relationships among ideas. Concept maps harness your visual sense to understand complex material “at a glance.” They also give you the flexibility to move from one idea to another and back easily.

To develop a concept map, start by using your reading to rank the ideas by level of detail (from high-level or abstract ideas to detailed facts). Select an overriding idea (high level or abstract) from the text’s headings and place it in a circle in the middle of the page. Then create branches off that circle to record the more detailed information, creating additional limbs as you need them. Arrange the branches with others that interrelate closely. When a new high-level idea is presented, create a new circle with its own branches. Link together circles or concepts that are related. Use arrows and symbols to capture the relationship between the ideas. For example, an arrow may be used to illustrate cause or effect, a double-pointed arrow to illustrate dependence, or a dotted arrow to illustrate impact or effect.

If this is the first time you have used the concept map method, start with the chapter title as your center and create branches for each section within the chapter. Make sure you phrase each item as a question.

As with all note-taking methods, you should summarize the chart in one or two paragraphs of your own words after class.

Step 3: Review What You Read

When you have completed notes for all of the sections in the assigned reading, you should review what you have read. Start by answering these questions: “What did I learn?” and “What does it mean?”

Next, write a summary of your assigned reading, in your own words, at the end of your notes. Working from your notes, cover up the answers to your questions and answer each of your questions aloud. (Yes, out loud. Memory is improved by using as many senses as possible.) Think about how each idea relates to material the instructor is covering in class. Think about how this new knowledge may be applied in your next class.

If the text has review questions at the end of the chapter, answer those, too. Talk to other students about the reading assignment. Merge your reading notes with your class notes and review both together. How does your reading increase your understanding of what you have covered in class and vice versa?

Step 4: Develop an Outline

After you have reviewed your notes, the next step of the reading process is to develop an outline.

Outlines allow you to prioritize the material you have read. Key ideas are written to the left of the page, subordinate ideas are then indented, and details of the subordinate ideas can be indented further. To further organize your ideas, you can use the typical outlining numbering scheme (starting with roman numerals for key ideas, moving to capital letters on the first subordinate level, Arabic numbers for the next level, and lowercase letters following.)

At first you may have trouble identifying when the text moves from one idea to another. This takes practice and experience, so don’t give up! In the early stages you should use the text’s headings and subheading to determine the key ideas.

If you are using your laptop computer for taking notes, a basic word processing application (like Microsoft Word or Google Docs) is very effective. Format your document by selecting the outline format from the format bullets menu. Use the increase or decrease indent buttons to navigate the level of importance you want to give each item. The software will take care of the numbering for you!

Additional Strategies

Following are some strategies you can use to enhance your reading even further:

- Pace yourself. Figure out how much time you have to complete the assignment. Divide the assignment into smaller blocks rather than trying to read the entire assignment in one sitting. If you have a week to do the assignment, for example, divide the work into five daily blocks, not seven; that way you will not be behind if something comes up to prevent you from doing your work on a given day. If everything works out on schedule, you will end up with an extra day for review.

- Schedule your reading. Set aside blocks of time, preferably at the time of the day when you are most alert, to do your reading assignments. Do not just leave them for the end of the day after completing written and other assignments.

- Get yourself in the right space. Choose to read in a quiet, well-lit space. Your chair should be comfortable but provide good support. Libraries were designed for reading—they should be your first option! Do not use your bed for reading textbooks; since the time you were read bedtime stories, you have probably associated reading in bed with preparation for sleeping. The combination of the cozy bed, comforting memories, and dry text is sure to invite some shut-eye!

- Avoid distractions. Active reading takes place in your short-term memory. Every time you move from task to task, you have to “reboot” your short-term memory and you lose the continuity of active reading. Multitasking—listening to music or texting on your cell while you read—will cause you to lose your place and force you to start over again. Every time you lose focus, you cut your effectiveness and increase the amount of time you need to complete the assignment.

- Avoid reading fatigue. Work for about fifty minutes, and then give yourself a break for five to ten minutes. Put down the book, walk around, get a snack, stretch, or do some deep knee bends. Short physical activity will do wonders to help you feel refreshed.

- Read your most difficult assignments early in your reading time, when you are freshest.

- Make your reading interesting. Try connecting the material you are reading with your class lectures or with other chapters. Ask yourself where you disagree with the author. Approach finding answers to your questions like an investigative reporter. Carry on a mental conversation with the author.

Complete this short quiz to test your understanding of the information.

5.4 Dealing with Special Texts

While the active reading process outlined earlier is very useful for most assignments, you should consider some additional strategies for reading assignments in other subjects.

Mathematics Texts

Mathematics present unique challenges in that they typically contain a great number of formulas, charts, sample problems, and exercises. Follow these guidelines:

- Do not skip over these special elements as you work through the text.

- Read the formulas and make sure you understand the meaning of all the factors.

- Substitute actual numbers for the variables and work through the formula.

- Make formulas real by applying them to real-life situations.

- Do all exercises within the assigned text to make sure you understand the material.

- Since mathematical learning builds upon prior knowledge, do not go on to the next section until you have mastered the material in the current section.

- Seek help from the instructor or teaching assistant during office hours if need be.

Reading Graphics

You read earlier about noticing graphics in your text as a signal of important ideas. But it is equally important to understand what the graphics intend to convey. Textbooks contain tables, charts, maps, diagrams, illustrations, photographs, and the newest form of graphics—Internet URLs for accessing text and media material. Many students are tempted to skip over graphic material and focus only on the reading. Don’t. Take the time to read and understand your textbook’s graphics. They will increase your understanding, and because they engage different comprehension processes, they will create different kinds of memory links to help you remember the material.

To get the most out of graphic material, use your critical thinking skills and question why each illustration is present and what it means. Don’t just glance at the graphics; take time to read the title, caption, and any labeling in the illustration. In a chart, read the data labels to understand what is being shown or compared. Think about projecting the data points beyond the scope of the chart; what would happen next? Why?

Table 5.2 “Common Uses of Textbook Graphics” shows the most common graphic elements and notes what they do best. This knowledge may help guide your critical analysis of graphic elements.

Scientific Texts

Science occurs through the experimental process: posing hypotheses, and then using experimental data to prove or disprove them. When reading scientific texts, look for hypotheses and list them in the left column of your Cornell notes. Then make notes on the proof (or disproof) in the right column. In scientific studies these are as important as the questions you ask for other texts. Think critically about the hypotheses and the experiments used to prove or disprove them. Think about questions like these:

- Can the experiment or observation be repeated? Would it reach the same results?

- Why did these results occur? What kinds of changes would affect the results?

- How could you change the experiment design or method of observation? How would you measure your results?

- What are the conclusions reached about the results? Could the same results be interpreted in a different way?

Social Sciences Texts

Social sciences texts, such as those for history, economics, and political science classes, often involve interpretation where the authors’ points of view and theories are as important as the facts they present. Put your critical thinking skills into overdrive when you are reading these texts. As you read, ask yourself questions such as the following:

- Why is the author using this argument?

- Is it consistent with what we’re learning in class?

- Do I agree with this argument?

- Would someone with a different point of view dispute this argument?

- What key ideas would be used to support a counterargument?

Record your reflections in the margins and in your notes.

Social science courses often require you to read primary source documents. Primary sources include documents, letters, diaries, newspaper reports, financial reports, lab reports, and records that provide firsthand accounts of the events, practices, or conditions you are studying. Start by understanding the author(s) of the document and his or her agenda. Infer their intended audience. What response did the authors hope to get from their audience? Do you consider this a bias? How does that bias affect your thinking about the subject? Do you recognize personal biases that affect how you might interpret the document?

Foreign Language Texts

Reading texts in a foreign language is particularly challenging—but it also provides you with invaluable practice and many new vocabulary words in your “new” language. It is an effort that really pays off. Start by analyzing a short portion of the text (a sentence or two) to see what you do know. Remember that all languages are built on idioms as much as on individual words. Do any of the phrase structures look familiar? Can you infer the meaning of the sentences? Do they make sense based on the context? If you still can’t make out the meaning, choose one or two words to look up in your dictionary and try again. Look for longer words, which generally are the nouns and verbs that will give you meaning sooner. Don’t rely on a dictionary (or an online translator); a word-for-word translation does not always yield good results. For example, the Spanish phrase “Entre y tome asiento” might correctly be translated (word for word) as “Between and drink a seat,” which means nothing, rather than its actual meaning, “Come in and take a seat.”

Reading in a foreign language is hard and tiring work. Make sure you schedule significantly more time than you would normally allocate for reading in your own language and reward yourself with more frequent breaks. But don’t shy away from doing this work; the best way to learn a new language is practice, practice, practice.

Licenses and Attributions

CC Licensed Content, Shared Previously:

- Section 5.1 and 5.4 were adapted from Chapter 5 of Success in College; authored by the University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing through the eLearning Support Initiative. License: CC BY-NC 4.0

- Sections 5.2 and 5.3 was adapted from Chapter 4 and Chapter 5 of Success in College; authored by the University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing through the eLearning Support Initiative. License: CC BY-NC 4.0

Video Content

- “How to Speed Read Technical Information” by Iris Reading