Theme 3: Roadmaps to Change

The way we live into our vision requires a clear sense of our values and purpose but also clarity about our approach to change. What do we assume to be true about how change happens?

The way we live into our vision requires a clear sense of our values and purpose but also clarity about our approach to change. What do we assume to be true about how change happens?

Change is often assumed to follow a linear, causal pathway from the actions we take, to the outputs of these actions, to outcomes and impacts.

Change is messy. It’s not a straight path but rather a network of roads, travelled by many, and filled with potholes, pitfalls, and unexpected diversions. We set forth to overcome the destructive dynamics of patriarchy, racism, capitalism, colonialism, ageism, ableism, classism, homophobia and more, knowing that the road can be winding and dangerous.

- How do we together create these roads to ensure we get where we want to go?

- What can we contribute to the enabling conditions for change?

- How does this complement what others are doing, on the roads they are following?

- Who and what do we bring along to help us get to our destination?

- How will we overcome the many obstacles along the way?

Activity 5: How change happens

Activity 5: How change happens

We look at our experiences in movements for change (or at one of the case studies in this guide) and draw out our assumptions about how change happens, and how our own efforts contribute to the process of resisting, shifting, and building power. We will revisit and deepen these questions throughout the Guide, particularly in Chapter 6: Power and Strategy.

Materials: Antonio Machado quote (above)

Step 1: What do we assume about how change happens?

Plenary: Using the Antonio Machado quote for inspiration, we can reflect on some of our assumptions about the change process – which is certainly not as linear, causal, or predictable as some planning frameworks indicate. Think about a change process led by movements in your context (or refer to one of the case studies in this guide). What do you observe about what makes change possible and what some of the important ingredients are? Consider these questions:

- Who or what creates the ‘enabling conditions’ – or lays the groundwork for social change to happen?

- Which different actors and organized groups contribute to the change process?

- How do different groups’ actions complement each other? Are there tensions?

- What can we learn from this reflection about the ingredients and actions that might be needed to advance our vision and agenda?

- Will our change efforts benefit from complementary strategies? Might there be conflict with other actors? And if yes, who? Where? Why?

Small groups: Each group takes a different question from this list (or other questions that arise in discussion) and generates three or four responses. What assumptions can you make about how social change happens?

Plenary: Small groups share their key thoughts. Draw out highlights from each one and open up to further discussion.

Share the quote Naming the Moment, inspired by Latin American experiences of struggle. Invite someone to read it aloud. Ask:

- What are the key assumptions in Naming the Moment?

- How do they enrich or challenge your thinking?

- What do you feel is the most important insight about power? About how change happens?

- What questions does it raise for you and your organization?

Download this activity.

Naming the moment

“When we do this analysis, we assume that …

… our social situation is filled with tensions between social groups and within them.

… history is made as these groups come into conflict and resolve conflict.

… some groups have power and privilege at the expense of other groups.

… this oppression is unjust and we must stop it.

… if we want to participate actively in history, we must understand the present as well as the past.

… we can learn to interpret history, evaluate past actions, judge present situations, and project the future.

… because things are always changing, we must continually clarify what we are working for.

… to be effective, we must assess the strengths and weaknesses of our own group and those working with and against us.

… at any moment there is a particular interrelationship of economic, political, and ideological forces.

… these power relationships shift from one moment to another.

… when we plan actions, our strategy and tactics must take into account these forces and relationships.

… we can find the free space that this particular moment offers.

… we can identify and seize the moment for change.”

Extract from Naming the moment, Deborah Barndt15

How does change happen?

Common assumptions in the NGO world are that policy drives change, that information changes minds, and that change is a straight line. But history and our own experiences give us plenty of examples to show that policy and information matter but politics, power, and mindsets are much more complex than that. Rather than a steady, linear progression toward justice and rights, it is clear that change always generates conflict and that struggle takes on new contours as contexts and power shifts.

This Guide uses a set of case studies that incorporate a broad array of strategies, both short and long term, that build power and leadership for communities and movements while advancing change at multiple levels. The case studies illuminate the critical importance of organising and movements in enabling people to resist oppressive forms of power, demand democratic and responsive governance, protect themselves from backlash and repression, create solutions and sustain the advances they make. Ultimately, creating change is about changing the balance of power through the organised efforts and strategic action of people over time.

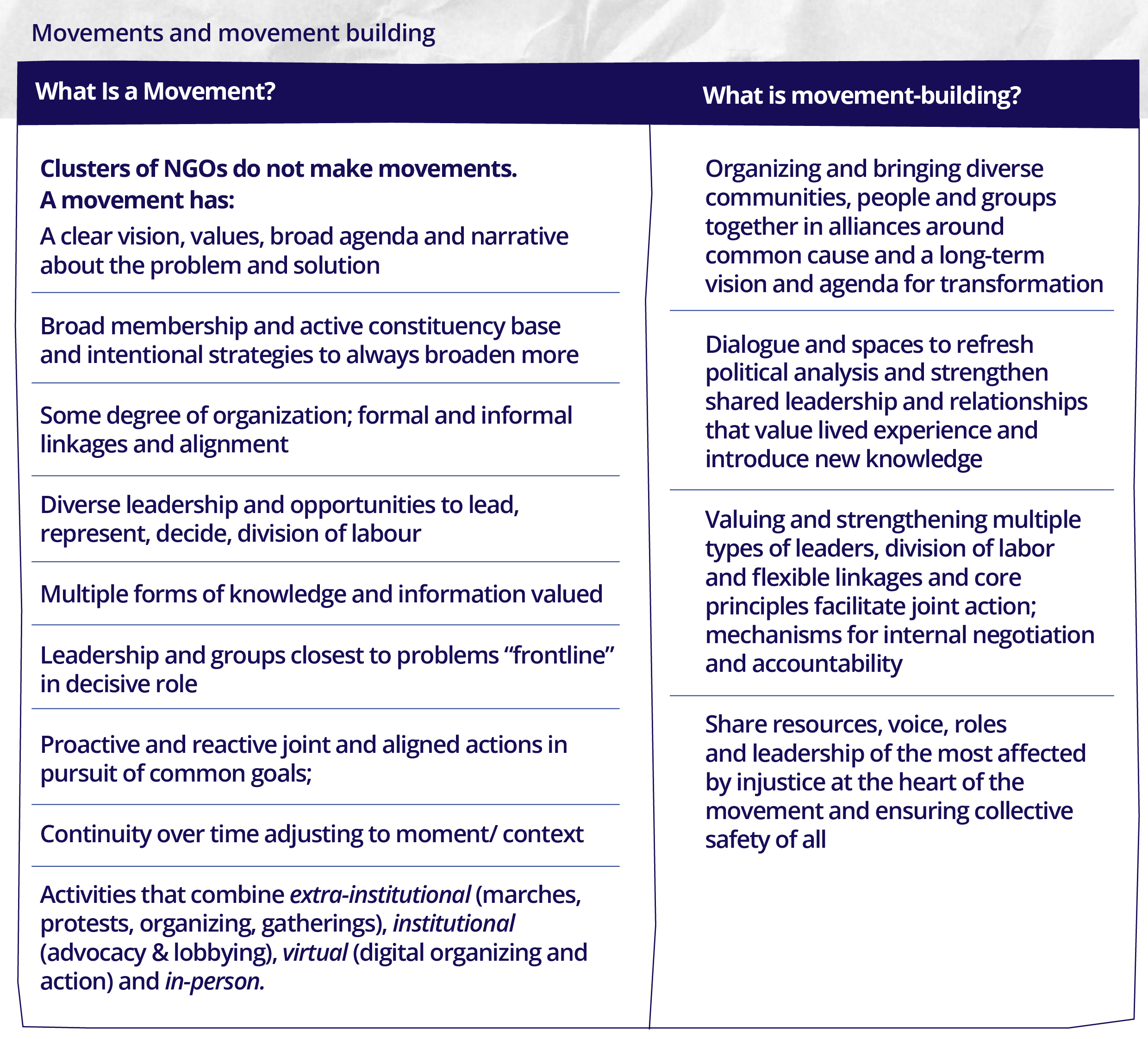

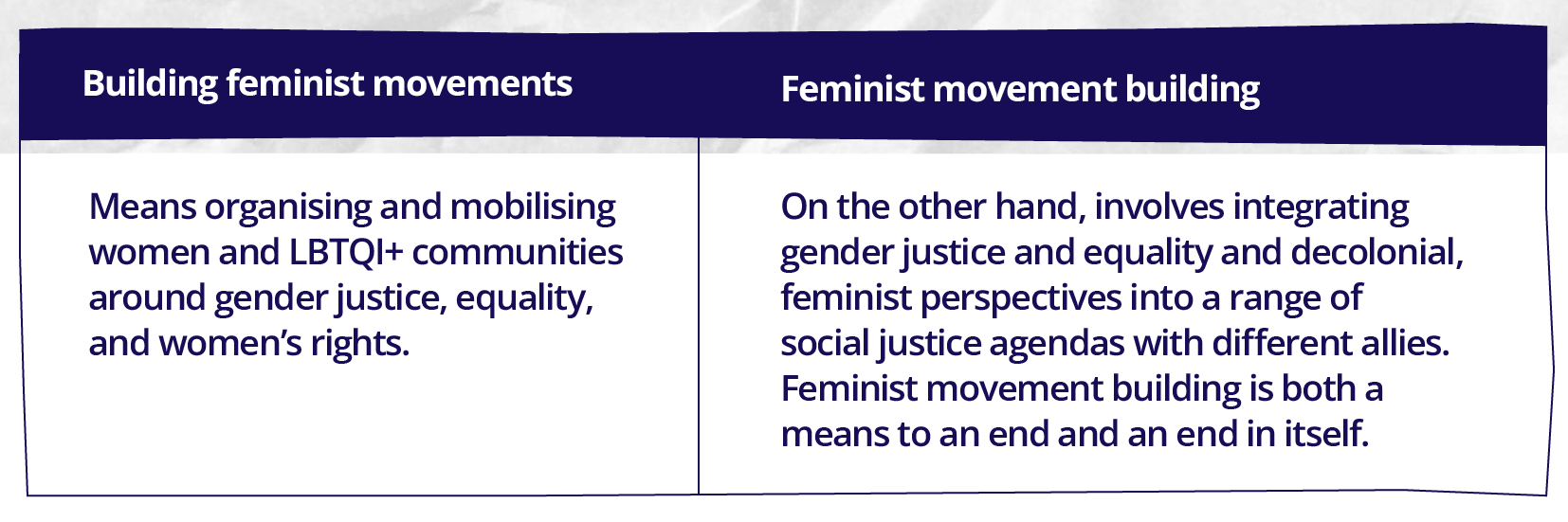

Defining movements and movement-building

In this Guide, we assume that movements and movement building are central to change. But these terms are often overused and misused. ‘Movement’ is used to describe everything from a handful of NGOs in a global policy process to a street mobilisation or an online campaign around a hashtag. All of these things may have elements of movements and movement building. We need to be precise about our definitions so that we are clear about our approach to change.

Download handout: Movements and movement-building.

Social justice movements are formed and driven by the power of multiple people and organisations brought together by their common problems and different struggles – from racial, gender, and climate justice to women’s, labour, and indigenous people’s rights. Movements weave the voices and concerns of many players into an ever wider and deeper force for change. Often catalysed by a pivotal event or an inspiring figure, movements are many years in the making through the often invisible organising among communities and organisations. We may not witness that invisible organising until a pivotal event occurs. That was the case in the USA with the Movement for Black Lives. The murder of George Floyd in 2020 didn’t create the movement, but it mobilised and amplified it.

Social justice movements are formed and driven by the power of multiple people and organisations brought together by their common problems and different struggles – from racial, gender, and climate justice to women’s, labour, and indigenous people’s rights. Movements weave the voices and concerns of many players into an ever wider and deeper force for change. Often catalysed by a pivotal event or an inspiring figure, movements are many years in the making through the often invisible organising among communities and organisations. We may not witness that invisible organising until a pivotal event occurs. That was the case in the USA with the Movement for Black Lives. The murder of George Floyd in 2020 didn’t create the movement, but it mobilised and amplified it.

In finding common ground and purpose, movements can develop strategies that align with their desire to challenge the systemic power dynamics at the core of oppression and violence. Operating under a broad and overarching vision and agenda, some movements often function loosely, without clear coordination. In such instances, certain groups serve as catalytic hubs that generate ideas and actions, motivating other, more dispersed groups to join. In other configurations, one or two organisations initiate actions that generate a movement, are recognised as its primary leaders, and establish clearer structures of participation and coordination.

Feminist Movement Building

Understanding power and developing political consciousness are at the heart of feminist movement building. As people build their own analysis of the economic, political, and social dynamics that shape their lives and contexts, they are able to identify shared problems and needs.

This process is the foundation of organising for collective power by helping transform practical needs – clean water, protection from violence, access to land – into a shared commitment that sparks and sustains movements for change.

Activity 6: What do we mean by ‘movements’?

Activity 6: What do we mean by ‘movements’?

Materials: paper and markers, handout: Defining movements and movement-building

Plenary: Introduce the activity and invite people to brainstorm:

- What is the first word that comes to mind when I say ‘social justice movement’?

Note responses on a flip chart.

Share and discuss the quote from Srilatha Batliwala as a kick start and/or the handout: Movement story: Treatment Action Campaign.

Small groups: Discuss:

- In your experience, what is a social movement?

- How are social movements organised? How do they come together?

List five key elements of movement building on a flip chart.

Individually: Make a drawing that reflects what a social movement means to you.

Plenary: Each group posts their drawings on a wall and, after a brief gallery walk, groups read out their five points. Together, discuss what you’ve heard and create working definitions of ‘a movement’ and ‘movement building’.

You might also ask:

- What are the features of different kinds of movements? Can you think of examples?

- How do movements operate? What are some key characteristics?

- What are some of the methods of organising, leadership, and decision-making?

- What formal or informal groups, alliances, or coalitions are movements made up of?

- And what do movements contribute to larger eco-systems of change?

Explore differences of opinion and areas of agreement.

Share the handout Movements and movement building for individuals to read to themselves or for a volunteer to read aloud. Then facilitate a plenary discussion.

- How do these definitions and stages enrich or contrast from our own definitions?

- How does this information help us understand movements that are active in our contexts and their contributions to change efforts?

- What is distinct or different about feminist movement building?

- How does our understanding of movements shape our ideas for how change happens?

Download this activity.

A movement story: Treatment Action Campaign

Responding to the HIV-AIDS epidemic in 1990s South Africa, the Treatment Action Campaign (TAC) organised HIV+ people to gain better treatment and confront stigma. Started by anti-apartheid HIV activists, TAC grew into a dynamic social justice movement. A powerful factor was TAC’s ability to attract and involve strategic allies – from international organisations such as Doctors Without Borders to local community groups, faith-based networks, labour unions, children’s organisations, legal support and research institutions, and health-service associations among others.

A membership-based organisation, TAC, began with a centralised leadership structure in which key community members and allies made decisions and took action with great agility. Later, TAC developed local branches across the country, and this allowed for more direct community participation, including voting on major movement decisions and working as HIV educators and promoters with government health centres. Despite challenges, TAC affected all levels of power including government, corporations, and the invisible systems of beliefs and norms that stigmatise HIV and reinforce people’s sense of powerlessness. TAC has achieved substantial impact – improving the health and dignity of people living with HIV as well as the entire health system and even levels of democratic participation. A variety of factors contributed to TAC’s success, including its founders’ experience both in South Africa’s liberation struggle and in being HIV positive; the resultant political trust; the agility and efficient coordination with which TAC could respond to changing power dynamics; and the scope and creativity of its strategies – from those aimed at the expansion, education, and participation of its members and allies, to the combination of confrontational direct actions with more traditional advocacy and communication approaches.

Download handout: A movement story: The Treatment Action Campaign.

____________________________

13 Tanzanian feminist, diplomat, and educator.

14 “Traveler, There Is No Path”. Antonio Machado, trans. Willis Barnstone from Antonio Machado, Border of a Dream: Selected Poems, Copper Canyon Press, 2004

15 Barndt, Deborah, Naming the Moment: Political Analysis for Action. A Manual for Community Groups, The Moment Project, The Centre for Social Faith and Justice, Toronto, 1991.

16 Srilatha Batliwala, “All About Movements: Why building movements creates deeper change”, CREA 2020.